The consensus view is that pragmatism is very American, particularly in its early development. Founders of the movement are supposed to have given philosophical expression to some ideas or feelings or principles (or something) uniquely characteristic of the American nation. To take one example almost at random, Scheffler’s classic study calls pragmatism “a distinctively American contribution to philosophy” (Reference Scheffler1974/2012, i, my italics), and this phrase—a fortiori, the interpretive attitude the phrase encapsulates—has been a commonplace in the relevant literature over at least the last half century, if not longer (e.g., West Reference West1989, 54; Stuhr Reference Stuhr1997, 23, 26, 31, 32; Burke Reference Burke2013, xi; Aikin and Talisse Reference Aikin and Talisse2017, 6).

There are a myriad of reasons why using a national lens to bring pragmatism into focus is deeply misleading, in my view.Footnote 1 But in this short essay my argument will be microcosmic. I will mainly examine the provenance of a single, curious term that William James often used in connection with his own pragmatism. The term is Denkmittel, an uncommon German contraction of Denk (thought) and Mittel (instrument).Footnote 2 James’s Central European sources for this now-forgotten bit of philosophical jargon provide a small illustration of a bigger historical point that too often gets obscured. Pragmatism—James’s pragmatism, at least—was both allied with and inspired by a broader sweep of scientific instrumentalism that was already flourishing in fin de siècle European philosophy.

This is not to deny that Peirce, Wright, Royce, and other Americans were also important inspirations for James. But the mythology of the Metaphysical Club (as examined in, e.g., Menand Reference Menand2001) should not blind us to the transnational philosophical conversations in which each of these thinkers, in their own very different ways, participated.

Scholarship about pragmatism too often flirts with intellectual exceptionalism. For instance, one commentator says that a commitment to “the unity and continuity of belief and action” was what made pragmatism “distinctively American” (Stuhr Reference Stuhr1997, 23). But non-American philosophers were also busy developing accounts of the close connection between belief and action, accounts that portrayed some central scientific concepts not as reality mirrors but as instruments for handling our environment. And James self-consciously sought to position his own pragmatism as but a local chapter of a broader alliance of such scientific instrumentalists.

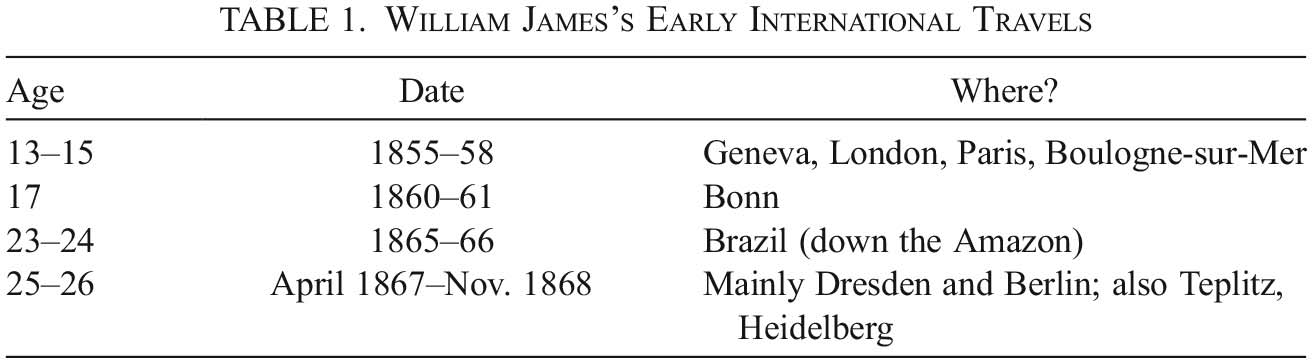

James had a famously international upbringing made possible by his eccentric father’s hereditary wealth and, perhaps, made necessary by the father’s intellectually demanding style of parenting.Footnote 3 Between ages 13 and 26 James would spend about as much time abroad as he would in the United States (see table 1). Long stays in Switzerland, England, France, Germany, and Brazil left him not only fluent in French and German but also with a firmly international outlook.

Table 1. William James’s Early International Travels

| Age | Date | Where? |

|---|---|---|

| 13–15 | 1855–58 | Geneva, London, Paris, Boulogne-sur-Mer |

| 17 | 1860–61 | Bonn |

| 23–24 | 1865–66 | Brazil (down the Amazon) |

| 25–26 | April 1867–Nov. 1868 | Mainly Dresden and Berlin; also Teplitz, Heidelberg |

It is well known that James’s 1898 lecture “Philosophical Conceptions and Practical Results”—and his 1907 blockbuster Pragmatism—were crucial to fomenting the pragmatist movement. But if fomenting a “national” movement means systematizing and developing ideas distinctive to the nation in question, that is a striking distortion of James’s actual education and, as I will illustrate, of his own self-understanding.

James often positioned his work as part of a scientific “tendency” in philosophy that was already being exemplified, he thought, by important European figures who shared an instrumentalist bent. In Pragmatism, he cited as fellow travelers Ernst Mach, Christoph von Sigwart, Wilhelm Ostwald, Karl Pearson, Gaston Milhaud, Henri Poincaré, Pierre Duhem, and Théodore Ruyssen (Reference James, Bowers and Skrupskelis1907/1975, 34, 93).Footnote 4 As James articulated and defended his own pragmatism, he often offered these kinds of international roll calls. In his 1904 review of F. C. S. Schiller’s Humanism, to give another example, James wrote:

Thus has arisen the pragmatism of Pearson in England, of Mach in Austria, and of the somewhat more reluctant Poincaré in France, all of whom say that our sciences are but Denkmittel—“true” in no other sense than that of yielding a conceptual shorthand, economical for our descriptions. Thus does Simmel in Berlin suggest that no human conception whatever is more than an instrument of biological utility;Footnote 5 and that if it be successfully that, we may call it true, whatever it resembles or fails to resemble. Bergson, and more particularly his disciples Wilbois, Le Roy, and others in France, have defended a very similar doctrine. Ostwald in Leipzig, with his “Energetics,” belongs to the same school, which has received the most thoroughgoingly philosophical of its expressions here in America, in the publications of Professor Dewey and his pupils in Chicago University, publications of which the volume “Studies in Logical Theory” (1903) forms only the most systematized installment. (Reference James, Burkhardt, Bowers and Skrupskelis1987, 551)

What James thought tied the American brand of pragmatism with this broader group of European instrumentalists (as we may loosely call them) was apparently the shared view that scientific theories amount to “conceptual shorthand, economical for our descriptions” rather than quasi-images meant to “resemble” their objects.Footnote 6 A conceptual shorthand is to be assessed as an “instrument of … utility”—that is, as an instrument that guides action—and then counted as true if the action guidance is successful.

Let us now take a closer look at this construal of concepts as thought-instruments (Denkmittel). James began using the latter, German phrase regularly in 1903 to describe concepts or theories that we retain because they are helpful for organizing experience.Footnote 7 There appear to be three plausible sources for James’s use of the term, and each source illustrates a characteristically pragmatist theme that is actually anchored in German-language philosophical trends.

One obvious source is Mach, the only native German speaker of the three persons whom James initially mentions as holding that “our sciences are but Denkmittel.” An early work in which Mach uses the term is his 1883 Die Mechanik in ihrer Entwickelung: Historisch-kritisch dargestellt. In one important passage, Mach suggests that there is a trade-off in science between scope, on the one hand, and descriptive and predictive precision, on the other (Reference Mach1883, 476).Footnote 8 The sacrifice of a wide scope that various sciences had made in order to achieve high precision was mitigated, Mach thought, by their joining together to achieve a fruitful “division of labor” across the sciences at large.Footnote 9 Once a division of labor was in place, this freed each science to develop highly precise, conceptual “tools of the trade” (Mach’s phrase). These are what Mach called Denkmitteln—instruments of thought. James read and heavily notated his copy of Mach’s Mechanik. This entire Denkmittel passage is emphasized in James’s copy with a sideline, along with “NB” in James’s hand.Footnote 10

Mach warned his readers not to treat these Denkmitteln (his examples include the concepts of mass, force, and atom) as picking out real, natural objects. There are no things in the world called “forces” that act on other things called “atoms,” according to Mach. Instead, he held that physics gives precise and artificial definitions to concepts like “force” and “atom” for the purpose of efficiently guiding action. These Denkmitteln give us economical ways to predict what will happen so that we can thrive as biological creatures in our respective environments (Mach Reference Mach1883, 476).

Mach’s emphasis on scientific concepts as instruments—his instrumentalism, as I have been calling it—looks a lot like pragmatism. But it was a homegrown sort of pragmatism that Mach developed before any serious engagement with James’s philosophy. Note the relatively early date of this passage (1883—again, James began using Denkmittel only in 1903). If there was an influence here, it likely went from Mach to James, not vice versa.Footnote 11

Still, James’s other uses of Denkmittel suggest that there is more to his appropriation of this term than that he simply borrowed it from Mach. For consider this related instance:

In practical talk, a man’s common sense means his good judgment, his freedom from excentricity [sic], his gumption, to use the vernacular word. In philosophy it means something entirely different, it means his use of certain intellectual forms or categories of thought. Were we lobsters, or bees, it might be that our organization would have led to our using quite different modes from these of apprehending our experiences. It might be too (we cannot dogmatically deny this) that such categories, unimaginable by us to-day, would have proved on the whole as serviceable for handling our experiences mentally as those which we actually use.

If this sounds paradoxical to anyone, let him think of analytical geometry. The identical figures which Euclid defined by intrinsic relations were defined by Descartes by the relations of their points to adventitious co-ordinates, the result being an absolutely different and vastly more potent way of handling curves. All our conceptions are what the Germans call denkmittel, means by which we handle facts by thinking them. Experience merely as such doesn’t come ticketed and labeled, we have first to discover what it is. Kant speaks of it as being in its first intention a gewühl der erscheinungen [a chaos of appearances], a rhapsodie der wahrnehmungen [a rhapsody of perceptions], a mere motley which we have to unify by our wits. (Reference James, Bowers and Skrupskelis1907/1975, 84; for related usages in 1903–4, see James Reference James, Burkhardt, Bowers and Skrupskelis1988a, 9, and in 1904, see James Reference James, Burkhardt, Bowers and Skrupskelis1909/1978, 44)

The reference to Kant, as well as the application of the notion of Denkmittel not just to theoretical tools in science but also to psychological categories we might use to organize experience, alerts us that there is more going on here than just an appropriation of Mach’s particular brand of instrumentalism about science.

We gain some insight by noticing that the vogue for this term was originally due to Kurd Lasswitz, a German historian, philosopher, and science fiction author who was on the fringes of the Marburg school of neo-Kantianism. After corresponding with one of Hermann Cohen’s critics (the mathematician Georg Cantor), Lasswitz—then a high school teacher—began developing some themes from Cohen (Reference Cohen1883) in his own work on the history and philosophy of atomism in physics (Giovanelli Reference Giovanelli2016; Reference Giovanelli2017, 310). Although he never held an appointment at Marburg, through this work he became a respected figure among the so-called Marburg school.

Perry reports that Lasswitz’s masterpiece, the 1890 Geschichte der Atomistik vom Mittelalter bis Newton, was the other most important source James relied on for the history of science, along with Mach’s Mechanik (Perry Reference Perry1935, 1.491n22). There are several mentions of Lasswitz in James’s published work, for example, a reference in 1892 to the Geschichte as “Lasswitz’s great history” of atomism (James Reference James, Burkhardt, Bowers and Skrupskelis1987, 434).Footnote 12 James had read the Geschichte in November 1892 (Perry Reference Perry1935, 2.144) and then used the book in his teaching, most notably in his Philosophy 3 (on cosmology and the philosophy of nature) during the 1890s (1.490–92).

Lasswitz’s project is to explain the conditions (Bedingungen) on the possibility of having knowledge of the material world (Reference Lasswitz1890, 1.3). He claims that for it to be possible for a multiplicity of bodies to become phenomenally present, a subject must have knowledge (Erkenntnis) of some basic laws (ursprünglicher Gesetze; 1.43) that govern possible relations in what is experientially given. These unifying relations (Einheitsbeziehungen) he calls Denkmittel (1.44).

Lasswitzian Denkmittel are akin to naturalized Kantian categories and are part of the basic theoretical framework for Lasswitz’s research in the history and philosophy of science. He thinks that the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century was constituted by the replacement of the Aristotelian, more metaphysical thought-instrument of substance (“das Denkmittel der Substanzialität”) with a properly scientific thought-instrument of causality (“das Denkmittel der Kausalität”; Lasswitz Reference Lasswitz1890, 1.44).Footnote 13 In a Kantian spirit, thought-instruments, appropriately developed, are what make possible the objective, scientific representation of nature (1.8, 79). But unlike a more traditional Kantian category, Lasswitz’s Denkmittel are historically conditioned in that they undergo gradual change (“allmähliche Umbildung”; 1.79) over the course of human inquiry. Thus we are not to probe Denkmittel via the methods of psychology; we are to grasp their nature by studying the history of science (1.8).Footnote 14

Lasswitz’s use of this term in his history of atomism is important for understanding James’s own position in the larger pantheon of European instrumentalists. For this usage informed James’s appropriation, and it has a Marburgian provenance. It is possible that Mach’s own usage had an influence on Lasswitz, but it is likely that the major influence on the latter here was Cohen.Footnote 15

In any case, after Lasswitz had given Denkmittel such a central role in his 1890 book, the word began appearing with more frequency throughout German-language philosophy. It appears, in fact, in the work of a final German-language philosopher relevant to our discussion—Wilhelm Jerusalem, who greatly admired both Mach’s work and James’s. Unlike Lasswitz, Jerusalem was quite hostile to Kant and his followers and, in fact, published an extended attack on Cohen in particular in Der kritische Idealismus und die reine Logik: Ein Ruf im Streite (Critical idealism and pure logic: A reputation in dispute; Jerusalem Reference Jerusalem1905).

Right around the time James began using the term Denkmittel in his published writing, he had sent Jerusalem some admiring comments on the latter’s Reference Jerusalem1895 Die Urtheilsfunction,Footnote 16 where we find the following telling usage: “The unconscious, whose existence we in no way are able to prove through direct experience [Erfahrung], is for us an instrument of thought [ein Denkmittel] for the understanding [Verständnis] of psychic life that we cannot do without [entrathen]. One demands of an instrument of thought [einem Denkmittel] that it can be thought of without contradiction, and that it be useful [brauchbar]” (Jerusalem Reference Jerusalem1895, 12). Jerusalem used the word Denkmittel regularly, and unsurprisingly (given his intellectual sympathies) his usage is much closer to Mach’s than Lasswitz’s. Jerusalem’s Denkmittel do not name any observable entities in nature but are rather nothing but useful postulates for helping us make sense of what we do observe.

Jerusalem was one of the rare German philosophers of his era to champion James’s philosophical views, eventually producing the German translation of Pragmatism.Footnote 17 Still, what we might think of as Jerusalem’s pragmatism is originally indebted to Mach’s instrumentalism; Jerusalem found in James an American version of ideas he had already been attracted to in European sources (Uebel Reference Uebel2019).

Interestingly, one can find James’s fondness for the term Denkmittel coming full circle in Jerusalem’s translation of Pragmatism. Jerusalem of course preserves James’s actual usages of Denkmittel, but Jerusalem also introduces the term where it does not appear in the original English. For example, James (Reference James, Bowers and Skrupskelis1907/1975, 34, italics added) had written: “Any idea upon which we can ride, so to speak; any idea that will carry us prosperously from any one part of our experience to any other part, linking things satisfactorily, working securely, simplifying, saving labor; is true for just so much, true in so far forth, true instrumentally.” Jerusalem renders this italicized clause: “Jede solch Idee ist wahr als Denkmittel,” which literally means, “every such idea is true as an instrument of thought.”

Finally, we can see James (in the two lengthy passages of his that I have quoted) loosely combining the Machian and Marburgian usages of this term. James’s Denkmittel is at least intended to indicate a kind of instrumentalism especially about scientific theories, which comes through in the passage from James’s 1904 Schiller review quoted above (Reference James, Burkhardt, Bowers and Skrupskelis1987, 551). This is very much in the spirit of Mach and Jerusalem. But James does not confine his usage only to unobservables like atoms and forces, sometimes extending the word to cover “all our conceptions.” James suggests that conceptions are just mental instruments for handling our “gewühl der erscheinungen,” quoting Kant. The Marburgian ring to this less restrictive usage is only reinforced by James’s appeal to the historical rise of analytical geometry to illustrate his point. James’s more extended usage is more naturalistic than what we find in Kant (or even in Marburg neo-Kantianism) in that conceptions are not housed in any transcendental ego but are simply ideas that organisms happen to hit upon in the course of evolution.

Like other scientific philosophies of the day, James’s pragmatism was cosmopolitan in spirit.Footnote 18 I do not pretend to have captured the whole of that cosmopolitan spirit in this short essay. But by examining his appropriation of a German philosophical term of art, I hope to have illustrated how richly cross-pollinated James’s pragmatism was with diverse forms of scientific instrumentalism that were also flourishing across Western Europe and across many national boundaries.