Eastern European democracies are in a stranglehold. Some are governed by ethnonationalist populists who have gradually aggrandized executive power, subordinated the courts, undermined independent media and other accountability institutions, harassed opposition-leaning civil society actors, and waged a culture war against liberal values and the EU. In others, supposedly moderate mainstream parties have pursued similar policies with similar results while feigning cooperation with the EU. And even where democratizing and Europeanizing political forces govern, opposition or coalition partners push a populist agenda and polarization is on the rise. Despite sustained electoral competition, the zeitgeist is backsliding and illiberalism. How and why did the promise of Eastern European liberal democratic consolidation of the EU-accession 2000s fade?

The scholarly debate centers on the push of an attitudinal shift towards populism among the electorate (Noury and Roland Reference Noury and Roland2020; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Attewell, Rovny, Hooghe, Cotta and Isernia2020) and the pull from the emergence of charismatic populist political entrepreneurs (Stroschein Reference Stroschein2019; Pappas Reference Pappas and Zúquete2020), both facilitated by the proliferation of new media, which favors the populist communication style (De Vreese et al. Reference Vreese, Claes, Esser, Aalberg, Reinemann and Stanyer2018). Specifically, Eastern European voters and parties have drifted away from the green-alternative-libertarian (GAL) dimension towards the traditional-authoritarian-nationalist (TAN) part of the political spectrum, with previously moderate conservative parties taking a sharp and deleterious swerve to right-wing populism (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2021). The exogenous shocks of the 2008 financial crisis and the 2015 refugee crisis may go a long way to explain the timing of the populist tide (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2021; Bernhard forthcoming).

We propose an additional, endogenous process, which links the original sin of the post-Communist transition—state capture—to the rising stock of conspiracy theories and the resulting emergence of a conspiracy axis of competition. We begin with the observation that many countries in the region have captured states: polities in which a ruling elite conspires with an oligarchic circle to self-enrich, using illegal means to pursue private interests at the public’s expense (Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2000). Organizing in this manner matches the legal definition of a conspiracy. Because the judiciary is weak and media freedom is compromised by oligarchic ownership, the conspiracy continues unabated. One consequence of the unchecked corruption of the state captors are masses of disgruntled voters and the resulting electoral volatility and party system instability that has characterized Eastern European polities over the last three decades (Pop-Eleches Reference Pop-Eleches2010; Haughton and Deegan-Krause Reference Haughton and Deegan-Krause2020). Yet this does not make the job of the reformist opposition easy. The problem for the opposition is to convince the voters that there is a conspiracy (their state has been stolen) and that the opposition has a plan to end the status quo. Specifically, the problem is to keep the focus on the state-stealing conspiracy without also inviting other conspiratorial narratives about Great Power geopolitical plots, climate change skepticism, gender ideology challenges to traditional values, and immigration threats to the ethnonational core. Note that these positions can be simply traditional/conservative positions, but we focus on their conspiratorial rendering. For example, “George Soros funds gender studies departments to weaken traditional Eastern European identity,” or “Europe/Russia/other Great Powers divert immigration flows to Eastern Europe to undermine Eastern European statehood,” or “Climate change is a hoax that aims to destroy industrial competitors.” Any of these gateway conspiracy tropes can capture the reformist vote and lead it astray towards the view that powerful hidden forces operate in the background and regardless of who is officially in government, a small cabal controls events. Nothing but a true leader can be trusted to expose the various conspiracies. We argue that once voters are unmoored from the narrative of stability propagated by the state captors, it is difficult to keep them in the “there is one conspiracy” box. They become easy prey for these stray rebels who preach, at the extreme, anti-Semitic and authoritarian tropes.

The emergence of this conspiracy axis of competition undermines democracy. The stray rebel opposition is no better than the state captor incumbent, something that the latter may point out to burnish their image domestically and in front of mainstream European partners and the EU. Progressive voters face the impossible choice of supporting either thieving but (relatively or, at least, rhetorically) “moderate” governments or reformist movements with weak or unclear democratic credentials. The real pro-reformist opposition is drowned out, and the system calibrates on an ostensibly dynamic and changing—but in fact deeply system-reinforcing equilibrium—in which neither a win nor a loss of the governing party means a victory for democracy. Electoral competition and even turnovers in power can continue indefinitely, while the quality of democracy and the provision of rights steadily decline.

The equilibrium that we identify is not equivalent to and may yet prove more dangerous than the traditional democratic backsliding model. Bermeo (Reference Bermeo2016) sees democratic erosion as an incumbent-led process that unfolds through executive aggrandizement and institutional restructuring aimed at strategic electoral manipulation. Waldner and Lust (Reference Waldner and Lust2018) broaden the definition beyond incumbent behavior and posit a deterioration in two out of three dimensions—competition, participation, and accountability. Eastern European democratic decline, as we describe it, does not fit either definition well because it allows for continued high levels of competition and participation (the exception is Hungary). It is accountability, ever in short supply in the region, that dissipates even further under the rising stock of conspiracy theories among the electorate and the increasing reliance on their narratives by establishment parties and newcomers alike. While this process may not be backsliding per se, it does reduce democratic quality and may eventually produce enough support for authoritarian leaders who would curtail competition and participation as well. To use Bustikova and Guasti’s dichotomy, it is more likely to facilitate a “turn” away from liberal democracy than to be a temporary “swerve,” whose course can be corrected by a change of government (Bustikova and Guasti Reference Bustikova and Guasti2017).

Looking at the sources of liberal democratic failure in this novel way is particularly useful in the COVID-era. In Eastern Europe, pandemic backsliding indicators focused on executive aggrandizement and civil and political rights erosion have picked up minor to moderate problems across the region (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Luhrmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Alizada, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Ilchenko, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medz-ihorsky, Römer, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2019).Footnote 1 We argue that COVID infused new energy in the conspiracy theories circulating in Eastern Europe while health restrictions animated opposition movements in novel ways. The win has not been for the reformist opposition but for stray rebel challengers. Conceptually, we need to bring to research an emphasis on “degrees of conspiracism” in voter attitudes (related to but not equivalent to authoritarianism or populism), and measures to tap into conspiracism as a veritable axis for political competition. One needs to collect different indicators to pick this up. The most advanced dataset of democracy, V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Luhrmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Alizada, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Ilchenko, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medz-ihorsky, Römer, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2019), has measures that are only indirectly related to what we describe here (for example, V-Dem taps into how elites employ argumentation, whether the media is corrupt, and whether there are anti-systemic actors).

We also draw attention to the fact that political competition in the post-communist space interacts in important ways with electoral trends in Western Europe and the United States. The success of ethnonationalist populists abroad, as well as alliances between Eastern European state captors and Western European mainstream parties structure the political knowledge of post-Communist voters. So far, by promoting stability and partnering with Eastern perpetrators of state capture in the European Parliament (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020), the West has failed Eastern Europe’s true reformists. Analyzing Eastern European electoral competition through the lens of political stability, or the competition between “pro-Western” and “nationalist”’ actors has drawbacks as both of those have contradictory layers. Neither stability nor “Western”’ are unvarnished goods. Instability and non-Western need not be better.

From State Capture to World Government: How Authoritarianism Conditions Travel on the Conspiratorial Spectrum

The general definition of conspiracy theory, as used in political science, states:

[political conspiracy is] a secret arrangement between a small group of actors to usurp political or economic power, violate established rights, hide vital secrets, or illicitly cause widespread harm … a proposed explanation of events that cites as a main causal factor a small group of persons (the conspirators) acting in secret for their own benefit, against the common good.Footnote 2

The theory is the perception that a conspiracy has or is taking place. Conspiracies fundamentally rest on the two pillars of organization (to cause harm), and of information (to keep it from coming to light). The two tropes co-occur but are independently important and may be prioritized to different degrees by a specific narrative.

One difference between conspiracy theory and conspiracy in the legal sense is that the former typically cannot be proven, whereas the latter can lead to a fact-driven conviction in court. What actors such as Trump call a “deep state” is an example of a political conspiracy theory—a claim of a cabal where there would probably be none, according to a judge. In Eastern Europe, judges are not politically dependent as in Russia, China, and other authoritarian regimes, but they are not impartial adjudicators either. Rather, judiciaries and public prosecutions are self-serving autonomous agents who often collude with politicians to maintain the state capture status quo. Judicial councils (formal institutions of judicial self-government introduced with the mandate of fostering the rule of law) have backfired, creating a judicial fortress that pays lip service to the rule of law doctrine, but abuses the principle of judicial independence to eschew accountability and allow individual judges and prosecutors to engage in corruption and influence peddling (Kosař Reference Kosař2016; Popova Reference Popova2010, Reference Popova2012).Footnote 3 Instead of working in earnest to expose corruption, the prosecution opens dead-end investigations or files shoddy indictments, and the courts regularly hand down acquittals. In the end, few, if any, important players in the political conspiracy of state capture suffer any legal consequences (Innes Reference Innes2014; Popova and Post Reference Popova and Post2018).

Thus, in Eastern Europe, the captured state is a conspiracy that could be exposed by a judge, but, in practice, never is—making it more akin to a theory and moving it closer to the deep state narrative. The rule of law’s weakness is a double whammy for Eastern European democracies—not only do the institutions that are supposed to expose the conspiracy aid it, but their participation enhances societal perceptions that the political conspiracy is pervasive and omnipotent.Footnote 4

Existing research on conspiracy theories tends to focus on consolidated democracies, but its insights can travel to Eastern Europe as hypotheses. It views conspiracies as another form of public opinion and seeks to determine who—and under what conditions—responds to this form of political communication. Scholars have found that people with more political knowledge are less likely to endorse political rumors and conspiracies than their low-knowledge counterparts (Berinsky Reference Berinsky2017) and that people who believe more in supernatural phenomena are more inclined to believe in conspiracies (Oliver and Wood Reference Oliver and Wood2014). Proneness to fall for such narratives may originate in psychological predispositions such as anomie, authoritarianism, self-esteem, cynicism, and agreeableness. Trust in existing political institutions is negatively correlated with belief in conspiracies in general (Darwin, Neave, and Holmes Reference Darwin, Neave and Holmes2011; Douglas and Sutton Reference Douglas and Sutton2008; Goertzel Reference Goertzel2014; Sutton and Douglas Reference Sutton, Douglas, van Prooijen and van Lange2014). Trust in existing political institutions is negatively correlated with belief in conspiracies in general (Abalakina-Paap et al. Reference Abalakina-Paap, Stephan, Craig and Gregory1999). Uscinski, Klofstad and Atkinson (Reference Uscinski, Klofstad and Atkinson2016) find that conspiratorial predisposition is orthogonal to partisanship in the United States,Footnote 5 but belief in conspiracy theories predicts political behaviors including voter participation—in a negative direction.

The links between conspiratorial thinking and populism and authoritarianism are particularly interesting considering the rise to power of leaders like Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, and Rodrigo Duterte, all of whom have traded in conspiracies and presented a strong leader image. Political psychologists have linked the appeal of conspiracism to the “authoritarian personality.” The study of the authoritarian personality started as an attempt to understand fascism and Nazism (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1993). Some approaches to measuring such personality include survey items including (an additive scale of three items): “Under certain conditions dictatorship can be a better regime”; “Group interests should be subdued to the common good”; “Conflict over substantive political issues hurts the common good.” Political psychologists Feldman and Stenner have developed a child-rearing survey instrument to tap into the concept while avoiding the conceptual problems arising from measuring attitudes toward current political developments in order to explain one’s attitude toward current politics (‘do you approve of unelected leaders?’ used to measure support for coups).Footnote 6 The study of the authoritarian personality has produced agreement on the following three traits for authoritarians: 1) cognitive closure—conflict means a lot of information, making distinctions and escaping the latter means embracing conformity, surety; 2) action based on non-scientific/rational information—acting as a group is good and is independently-valuable of evidence-based action or policies; and 3) belief in a leader solely on the basis of them being “like us,” a member of an imagined community who is qualified to lead in a “natural” way.

Based on this research, one would expect to find a degree of correlation between a voter’s authoritarian personality profile and their belief in conspiracy theories, such as belief that the world is governed by a secret cabal. We offer an example from East-Central Europe, drawing on a survey in ten countries by GLOBSEC (Hajdu and Klingová Reference Hajdu and Klingová2020).Footnote 7 The survey included the question: “Which of the following forms of government is, according to you, better for your country?”—which includes the option “having a strong and decisive leader who does not have to bother with parliament or elections.” We use this question to code whether the respondent is prone to authoritarianism. The survey also had the question: “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements: world affairs are not decided by elected leaders but by secret groups aiming to establish a totalitarian world order?”—which includes four response categories, from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Figure 1 shows that, with one exception, the fraction of respondents agreeing that a strong ruler is right for their country, is monotonically increasing in their view that world affairs are being run by a self-regarding, secret cabal.

Figure 1 Believes country needs strong leader by whether respondent agrees world conspiracy exists

In interpreting the country graphs, we should bear in mind that the fraction who believe in world conspiracy is 50% or more in Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovakia and closer to 20% in Austria (agree), with most other countries in between. This is important: authoritarian predispositions and belief in conspiracy theories are correlated everywhere, but only in Eastern Europe (in contrast to, say, Western Europe) is the set of believers in conspiracy theories so extraordinarily large. The first implication for our argument is that the conspiracy axis of political competition is not a marginal phenomenon in Eastern Europe. Eastern European political actors who wish to activate and run on conspiracy narratives can quickly catch the attention of about half the electorate. Moreover, the conspiracy-prone electorate is positively pre-disposed towards authoritarian leaders, and therefore expanding and building up the conspiracy part of the political spectrum boosts the risk of democratic failure.

Why are so many Eastern Europeans susceptible to belief in conspiracy theories? While Eastern Europe has been fertile ground for conspiracism at least since the days of the Russian Empire, the post-Communist period has seen an upsurge in the phenomenon (Ortmann and Heathershaw Reference Ortmann and Heathershaw2012). The big push of large swaths of voters to conspiracism likely originated with state-capture. Work by Hellman and Kaufmann in the late 1990s spawned a large state capture literature (Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2000). They noted that during the unprecedented and uncharted transition away from the communist party state and its command economy, economic actors “have been able to shape the [new] rules of the game to their own advantage, at considerable social cost” (Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2000, p. 1). State capture fits the legal definition of conspiracy quite well—it takes shape in secret and it is clearly harmful to the public interest. Hellman’s other contribution to the Communist transitions literature even more clearly illustrates the political conspiracy—the winners from the first round of post-Communist reforms collude and hijack the reform process behind the scenes, outside of the electoral arena of competition and prevent further reform in order to continue collecting rents (Hellman Reference Hellman1998). Both “harm” and “secret” are part of the story.

This post-Communist form of state capture, which Grzymala-Busse calls institutional exploitation, is consistent with vigorous competition—the perpetrators of the conspiracy assume some risk of losing elections, but they also do not need to share their rents as they would in a clientelist system (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2008, 643). What looks like vigorous electoral competition is often a facade for “corporate competition between only nominally ‘political’ actors” (Innes Reference Innes2014, 89). Parties tend to be de-ideologized and follow the business-firm model of party organization pioneered in Southern Europe by Italy’s Forza Italia and Spain’s UCD (Hopkin and Paolucci Reference Hopkin and Paolucci1999). They are increasingly disconnected from voters and, instead, work towards furthering the private interests of shadow economic actors. The result is unstable and inconsistent policy positions, often to the detriment of public interest, and increasingly confused voters. In some states—Bulgaria, Montenegro, Slovakia—governing parties are closely intertwined with organized crime actors, leading some to describe the situation as the mafia owning the state (Naím Reference Naím2012).

The run up to EU accession brought a lot of optimism that sustained party competition (Grzymala-Busse and Luong Reference Grzymala-Busse and Luong2002) and EU conditionality (Vachudova Reference Vachudova2005) would gradually facilitate the creation of strong formal institutions of accountability and oversight (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2007). Over time, both factors would expose the political conspiracy and would gradually reduce vulnerability to oligarchic capture and institutional exploitation. The institutionalist view has been recently undermined by democratic decay in the front-runners of post-Communist state-building. Hungary’s consolidated party system buckled in the late 2000s under intensifying contentious politics, executive aggrandizement, and constitutional engineering (Bánkuti, Halmai, and Scheppele Reference Bánkuti, Halmai and Scheppele2012; Bernhard forthcoming). Orban’s Fidesz has captured the state and some of the major parties of the initial transition period have all but disappeared (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2019). Oligarchic capture is so complete that Hungary has been called a “mafia state” (Magyar et al. Reference Magyar2016). The main oversight and accountability institutions—Constitutional Court, ordinary judiciary, audit offices, public prosecution—have lost their political independence and are perceived as enablers and collaborators in the state capture conspiracy, rather than protectors of political competition and guarantors of the rule of law (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018; Halmai Reference Halmai2019; Kovács and Scheppele Reference Kovács and Scheppele2018). Ironically, in the other early democratic consolidation front-runner, Poland (and in Czechia to a lesser extent), the attack on accountability institutions came not from the state captors, but from populists claiming that they are exposing state capture and corruption and finishing the cleansing of the polity from the pernicious Communist legacy (Sadurski Reference Sadurski2019; Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018).

If pervasive, officially non-existent, state capture can lead many voters to question appearances, why or how do voters go beyond the state-capture conspiracies to acquire elaborate conspiratorial views? In part, this is a question of how the interaction between people’s existing predispositions and the incentives (and actions) of strategic actors produce movement toward further belief radicalization.

We present an illustration of the conspiracy axis of competition that has emerged in many Eastern European democracies. We highlight the problem Eastern European pro-reform oppositions face when navigating an electoral field where the real conspiracy (state capture) competes with other conspiracies, such as “COVID is a little flu/hoax/biological weapon.” Table 1 plots the conspiracy-matrix, with voters’ take on both the real and the imagined conspiracy. Eastern European publics face a more complicated decision as they evaluate the credibility of the COVID conspiracy theories that have circled the globe. They have to decide whether to believe that a government, likely involved in an oligarchic political conspiracy, is actually telling the truth on COVID. People can accept or reject both conspiracies or they can choose which conspiracy to believe. We choose this matrix to capture a situation in which some event grows the stock of conspiratorial narratives—by adding a line which is as exotic as the claim of a world government, namely, that COVID is a biological weapon created to enslave people. People who take up this narrative will likely be similar to those who already believe a number of questionable truths—but the raw reality of the pandemic likely grows the number of “hard-core” conspiracy believers further.

Table 1 Political and COVID conspiracy: A road map to types of voters

The pro-reform opposition actors press on to expose the real political conspiracy. The language used by reformist parties about state capture reads like a classic, hard-to-prove “political conspiracy” narrative: there is a well-hidden plot to engage in mass corruption and its existence can only be gleaned by episodic lapses in the system (say, leaked phone conversations), or by putting together many disparate events to find a pattern. In addition, reformists are likely to insist on restructuring formal institutions of oversight to boost their impartiality so they can expose the conspiracy. This discussion can be confusing. On the one hand, state captors push back by accusing reformists of distorting reality or insinuating that the reformists are representatives of competing state capture networks. For many voters, it is difficult to follow the disparate strands of evidence about the conspiracy. Wonky debates about the institutional setup of the judiciary and the prosecution quickly prove tedious. Therefore, a big portion of the electorate, who may occasionally notice and get worked up about individual corruption scandals, will largely remain in the fold of the mainstream corporate parties. They will bracket the issue of state capture and instead prefer to focus on the parties’ stated policy positions. In countries where the state captors emphasize political stability and feign European cooperation, these voters may buy into the notion that the political mainstream is gradually pursuing Europeanization and may even see their government as partnering with Europe’s top politicians—Merkel or Macron. In the COVID context, they take the government’s claims that it is following the scientific context at face value and do not foray into COVID conspiracies. We call these voters the conformists.

Still, rampant corruption will convince many voters to peel off from the corporate party system that has captured the state and recognize the existence of a political conspiracy. Eastern European polities, as we know, are full of disillusioned voters who are looking for mainstream party alternatives and are ready to exercise a protest vote. These peeling voters are in a quandary. They have discovered that the public signal they receive (“all is well”) and their private signal (“all is far from well”) are at loggerheads. Consequently, they lose trust in official institutions.

Some are firm in interpreting the fight against state capture as a good governance project, and they recognize that their main ally in pushing this agenda is the European Union. As a result, they also tend to embrace other fundamental European values, such as the rule of law, women’s, LGBTQ+, and minority rights. On the COVID dimension, they follow the mainstream European position and shun conspiratorial narratives. We call these voters the reformists.

However, once information cannot be anchored, it becomes increasingly difficult for voters to appraise the quality of the different narratives they are bombarded with. Who is to say that state capture is the only conspiracy out there? Because institutions are not working to separate far-fetched claims from more reasonable ones, any claim—including the claim that COVID is a biological weapon—can find an outside audience. Other examples of claims that can easily find converts among unmoored voters are: a world government cabal is attacking Christianity, discriminating against whites, pushing gender equality norms too far to weaken traditional values, all the way to familiar villains from previous conspiracy theories, such as Free Masons, the Rothchilds, Soros and the “sorosoids.” Some of these may be gateway conspiracies. For example, many people may have reservations about gender and minority rights, and sufficient exposure to these narratives (via the presentation of “evidence”) may push them into the most exotic, up-right box of “all is a conspiracy.” COVID rumors may play a similar role—with mask mandates and vaccination passports being used to drum up support for the extreme version of an origin of the pandemic in a tyrannical plot.

We further argue that who continues to travel up in the right column is a) predictable and b) subject to elite exploitation. The voters who leave the reformist box and embrace multiple conspiracies in addition to the state capture conspiracy are stray rebels. Stray rebels believe conspiracy is all around. When they look to the West, they tend to identify with political actors who push conspiratorial narratives, both about a “deep state” and about geopolitical and cultural plots against the nation-state and traditional values. They think that a leader like Trump (or even Putin) is needed domestically to fight both post-communist state capture and all the other dragons.

Elites tied to the governing party or parties may encourage entrepreneurs to propagate conspiracies in the hope of peeling off voters from the reformists. New parties that appeal to the stray rebels are likely less of a threat to the government because they usually lack a coherent agenda, their leaders can be co-opted, and the government can shine as the reasonable actor by comparison. Based on what we know about individual susceptibility to conspiracy narratives, we believe that voters with more authoritarian predispositions will be moved “up” in the right column—peeling off from the reformist bloc of “there is one conspiracy and it is the government” to “all is a conspiracy.” This also helps explain why many leaders in the stray rebel quadrant are populist and authoritarian-minded.

The final group of voters are the dupes. They fall for the conspiratorial narratives supplied by the ruling coalition and may get genuinely invested and worked up about them. At the same time, they are willing to take the state captors at their word when the latter deny the existence of a state capture conspiracy. These voters tend to be volatile in their electoral behavior and preferences and often display cognitively dissonant positions. Sometimes they vote for the ruling coalition, other times they vote for niche parties that further some of the conspiratorial narratives—nationalists and anti-Western parties, traditional family values parties, anti-immigration or climate change denial parties.

Traditionally, political competition in consolidated democracies occurred in the lower-left cell in which no conspiracies are alleged (Trump and the newly elected QAnoners in Congress are the exceptions that prove the rule). Working institutions keep the set of voters who doubt what they see and become alienated within limits. The rise of populist leaders and movements is a signal of some, but still relatively contained alienation. In Eastern Europe, however, most political competition occurs in the conspiracy column along what we call the new conspiracy axis. This new axis cuts across not only the traditional left-right spectrum, but also across the green-alternative-libertarian versus traditional-authoritarian-nationalist spectrum proposed by the Chapel Hill Expert Survey to describe the current party space in European democracies (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015). For a democratic breakthrough to take place, the state capture conspiracy should command voters’ attention - and the rest of the conspiratorial narratives should be dismissed. In practice, reformist oppositions face significant competition from stray rebel leaders, who, aided by external events, make significant inroads into the reformist camp. We next illustrate this dynamic at work close to the April 2021 Bulgarian elections and refer to other cases in the region.

The Conspiratorial Turn in the Fight against the Oligarchy in Eastern Europe

Bulgaria is a good example of the rise of a conspiracy axis and the detrimental effects on democratic governance of the competition between reformists and nationalist and populist stray rebels for the mantel of fighter against the oligarchy. Bulgaria is particularly blighted by state capture (Ganev Reference Ganev2007). While electoral competition has always been robust and turnovers in government frequent, the quality of accountability institutions—the courts and the media, especially—has gradually declined to levels seen more often in autocracies than in democracies (Popova Reference Popova2012; Raycheva and Peicheva Reference Raycheva and Peicheva2017). Since the first breakthrough by an unorthodox party—NDSV (National Movement Simeon II)—in 2001, Bulgaria has seen a revolving door of new party entrants, all claiming readiness to fight corruption and state capture and all falling short, whether because they embraced state capture while in office (NDSV, GERB) or because they strayed towards and prioritized alternative conspiracies (Ataka) or because they could not keep voters’ attention on a reformist agenda (Reformist Bloc) (Engkelbrekt and Kostadinova Reference Engelbrekt and Kostadinova2020). Ataka’s trailblazing use of geopolitical conspiracies and ethnonationalist anxiety, spawned additional entrants who straddle the “state capture is real or not” divide. Those who position themselves in opposition criticize the government’s corruption and vie for the stray rebel vote (Barekov’s Bulgaria Without Censorship); others who seek to enter the governing coalition emphasize alternative conspiracies and court the dupe vote (VMRO, Volya). Meanwhile, the mainstream parties that spawned post-communist state capture in the early 1990s, the BSP and the MRF have had a remarkably stable hold on the conformists, and even though they have alternated between governing coalition partners and ostensible opposition, they have managed to keep a tight grip on behind-the-scenes oligarchic power.

The 2021 parliamentary elections featured an attempt at a come-back by reformist actors competing as Democratic Bulgaria and two new formations also competing in the right column.Footnote 8 Democratic Bulgaria is a coalition between Hristo Ivanov’s Da, Bulgaria party and Radan Kanev’s Democrats for Strong Bulgaria, both unrepresented in the current parliament. Kanev is an incumbent Member of European Parliament (MEP), so currently distanced from domestic politics, but Ivanov has actively challenged GERB and its oligarchic governance model. He has long pushed rule of law reforms, briefly as a Minister of Justice, and in the last few years has focused on exposing the pernicious role of the procuracy in Bulgaria’s stalled anti-corruption and rule of law reforms. The failure of Da, Bulgaria to rally a sizable reformist vote illustrates the difficulty of selling the complex state capture conspiracy narrative to the average voter. On the state-capture axis, Democratic Bulgaria was challenged by two newcomers who competed for both the stray rebel and reformist vote. The first one is Ima Takuv Narod (ITN), fronted by TV talk show host Slavi Trifonov, who refused to discuss any specifics of his program beyond stressing that he would clean up after GERB. In 2020 interviews, however, he flirted with Euroskepticism and praised Dr. Atanas Mangarov, Bulgaria’s most popular COVID-skeptic. Incidentally, Dr. Mangarov ran for parliament on the ballot for a minor stray rebel formation on the left (ABV), illustrating the political salience of COVID conspiracies. The second newcomer is Stand Up-Mafia Out (IB-MV)—a coalition of the Poisonous Trio (two journalists and a lawyer who emerged out of anti-government protests in the summer) and former Ombudswoman and ex-Socialist, Maya Manolova. Nikolay Hadjigenov, the protest activist lawyer, and Manolova talk the reformist talk, but it remains to be seen whether they would walk the walk. Echoing Bolsonaro, Hadjigenov has repeatedly called COVID, “the little flu (flu-ling)” and has criticized lockdown measures as undemocratic and a tool for executive aggrandizement.

To look beyond the public positions of the newcomers and check whether they are, indeed, competing on the conspiracy axis with voters, we deployed a brief survey on Facebook. We fielded the survey among opposition activists on Facebook to study people who are least likely to be aligned with the governing coalition in Bulgaria. Social media surveys are known to represent the inclinations of activists well (Jäger Reference Jäger2020; Foos et al. Reference Foos, Kostadinov, Marinov and Schimmelfennig2020). We received responses from 356 participants on questions probing political attitudes, intent to vote, view on COVID vaccines, and on the fight against the oligarchy, both in Bulgaria and worldwide. We want to see whether the conspiracy narratives working at loggerheads can be identified in that data, and we also want to see the challenges faced by real opposition movements in the field.

First, we check who these respondents believe “fights the oligarchy.” Figure 2 shows the ranking. Opposition leaders, starting with Hristo Ivanov lead the way. Ivanov burnished his reformist credentials further the summer of 2020 by storming a guarded beach with a dinghy, managing to expose the fact that MRF’s former chairman and still reputed leader of the shadowy elites in power had illegally cordoned off public access. Government leaders, including the prime-minister, are at the bottom. Trifonov, the leader of ITN, and Babikian, one of the leaders of IB-MV, both of them stray rebels, are not that far behind Ivanov in the credit respondents give them as an oligarchy fighter. This suggests that all three are competing for the same votes. Evaluations of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump also suggest that the opposition is virtually evenly split between reformists and stray rebels. Over half and about one-third of respondents see Johnson and Trump respectively as fighters against the oligarchy, which suggests that these voters conceive of the oligarchy as a world phenomenon, rather than a domestic post-communist state capture phenomenon.

Figure 2 Who among these leaders fights the oligarchy, Bulgarian Facebook panel

Our argument is that, once unmoored, anti-establishment voters turn into drifters, open to the call of other conspiracy claims. We further argue that respondents’ antennae pick up the threat/unify aspect of further conspiracy-claiming, and that authoritarian predispositions would explain the openness to these conspiracy-is-ubiquitous narratives. We included a battery of four questions, measuring authoritarian predisposition as a tendency to expect obedience versus self-confidence in children (Feldman and Stenner Reference Feldman and Stenner1997). The attraction of this approach is that it does not invoke political attitudes, figures, or current events.

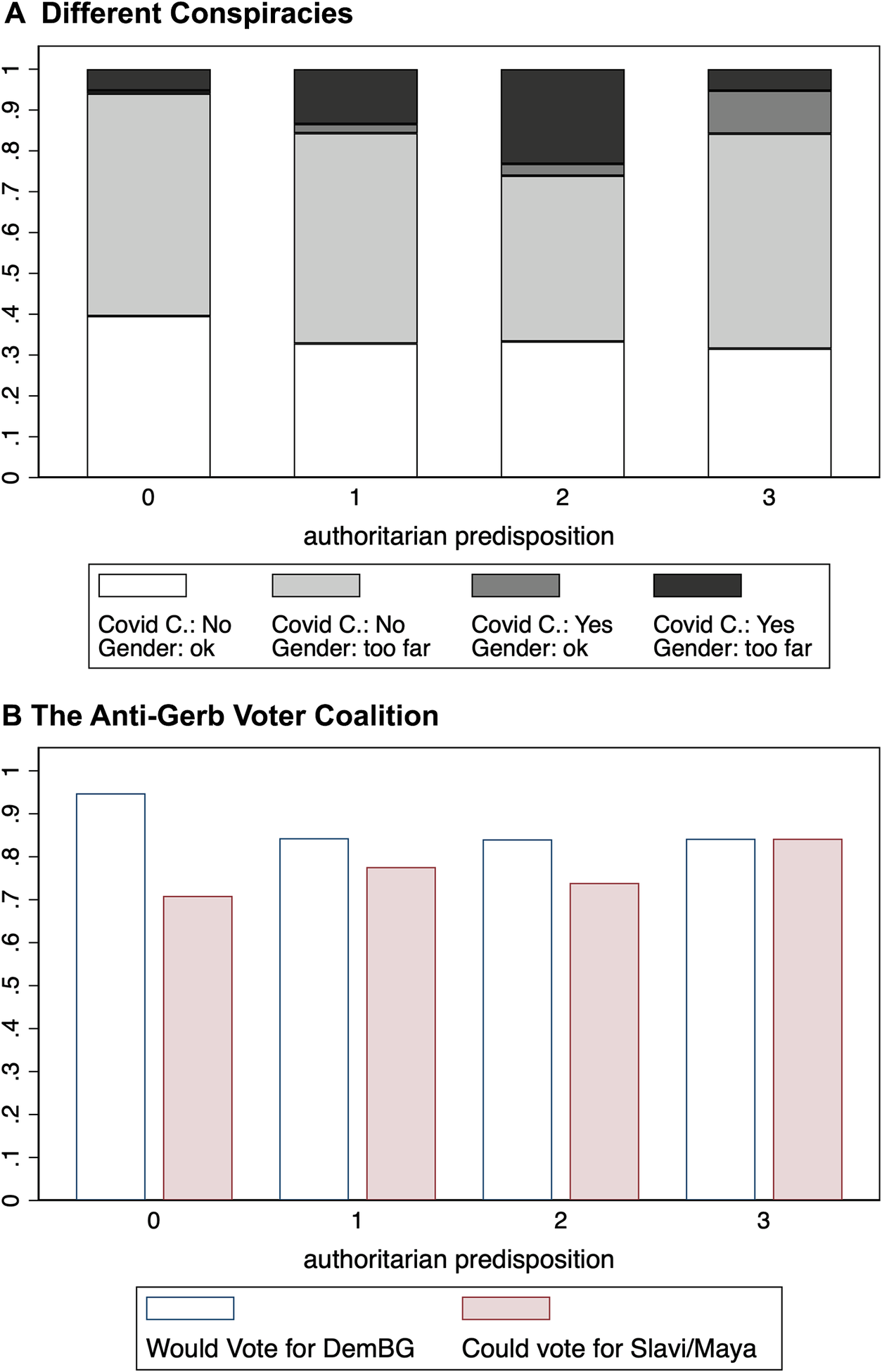

We plot two tendencies. One is what conspiracies people believe and the other is who they intend to vote for, within the competition available in the opposition ranks. Figure 3a shows that, as authoritarian predispositions increase, so does belief in conspiracy theories. Furthermore, the mix matters. There is a relatively smaller group believing the somewhat extreme claim that COVID was made to benefit a select circle, and a relatively large group that is open to the idea that movements for gender and minority rights have gone too far, a code word that borders on the trope about women and minorities taking over positions of power they do not deserve. The small all-conspiracy groups at the top of the bars and the small no-conspiracy bar at the bottom are the core constituents of the stray rebels and the reformists respectively. This shows up in figure 3b where authoritarian predispositions predict voting for and against two parties: less authoritarian types go for the reformist coalition that has Hristo Ivanov among its leaders, and the more authoritarian ones go for the more populist ticket of stray rebels Maya Manolova and Slavi Trifonov in the anti-GERB (the governing party) ticket (there are reasons to believe that both movements would sabotage reforms if elected).

Figure 3 Conspiracies and voting intentions by authoritarian predispositions

Note: Authoritarian predispositions are measured with child-rearing questions—Bulgarian Reformist Parties/Stray Rebels voters' Facebook Panel, n=356

The opposition is disparate, and not in ways expected or predicted by left-right, mainstream-challenger, or GAL-TAN spectra. Rather, the boundaries are more about where the bounds of the true conspiracy lie. The opposition is not necessarily populist and not in its entirety, and it is hard to compare the populism of the government to that of the opposition. There is a wide-open field for “poaching” the reformist vote. The COVID epidemic facilitated and accelerated this process by providing a push to the total conspiratorial stock available. It is no coincidence that the summer 2020 anti-government protests featured a mix of people with and without masks—reflecting the fact that for many voters, once the rebellion starts, it is hard to understand what the boundary should be—and why any authority should be respected. The corrosion of existing institutions—from academia to state agencies—provides an enabling condition for rumors and uncertainty to spread and turn mainstream.

This message often goes hand in hand with an all-conspiratorial, post-truth viewpoint (science is fake, whites are under threat, there are no facts, and so on). Because “Trump is not Merkel,” voters who are disillusioned with the status quo may recognize in him a force of reform or a force for the good. In an information-poor environment, for people who lose trust in the government, someone like Trump may be an inspiration both to reformists and to stray rebels.

In this setting, the pattern of international alignments matters. Voters and elites can use what happens in other countries as inspiration and validation. On the other hand, reformist parties in post-communist states have not always found an ally among mainstream parties in Western Europe. Established Western political elites have found working with ruling coalitions in Eastern Europe convenient. Especially in the Balkans, the EU has, in effect, propped up corrupt regimes with authoritarian tendencies through the enlargement process in the interest of maintaining stability in a previously volatile region (Bieber Reference Bieber2018; Kmezić Reference Kmezić, Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2019). In the European Parliament, the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Social Democrats (SD) have downplayed domestic opposition to ruling Eastern European coalitions responsible for state capture in order to continue benefiting from the votes that these corporate parties bring to the tally. In the process, the EU legitimizes local state-capture, reinforces the “all is a conspiracy” chorus, and, some argue, helps produce an authoritarian equilibrium (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020).

The increasing salience of the conspiracy cleavage has a profound effect on the reformist segment of East European party systems. It becomes harder for reformists to claim that a local political conspiracy to capture the state exists, but all other conspiracies—multiculturalist plot, EU threat to national sovereignty, lab-created COVID, 5G, and micro-chipping plots—are groundless. When the incumbents involved in state capture took COVID-realist positions (e.g., Orbán in Hungary, Vučić in Serbia, Borissov in Bulgaria), the reformists become subject to pressure on the COVID-denialist flank. The reformists’ positioning is further complicated by the support that the main European party families extend to incumbent state captors. Borissov’s GERB and Orbán’s Fidesz, and Croatia’s HDZ have all benefited from EPP support (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020). In the Balkans especially, entrenched incumbents have benefited from the EU’s purported emphasis on stability over democracy (Bieber Reference Bieber2018). It becomes increasingly untenable for reformists to seek to expose the local political conspiracy, while aligning themselves with the EU and its liberal values. The result is fragmentation of the reformist space and the rise of a new axis of competition—instead of competing with the mainstream parties over corruption, judicial reform and effective government and seek to peel off some of the conformist voters, the reformists now compete with the far-right, nationalists, and Euroskeptics over the sizable COVID—and vaccine-skeptic electorate.

In addition to our survey evidence from Bulgaria, recent elections in the region point to the growing fragmentation of the reformist vote over competing conspiracies. In Serbia, Vučić’s rhetorically pro-European, but increasingly authoritarian government was entering its second year of significant anti-government protests just as COVID’s first wave hit. After a brief flirtation with COVID-denialism, Vučić quickly adopted the scientific consensus position. He then used lockdown measures as a political instrument in the parliamentary election campaign—toughening up restrictions when he needed to suppress anti-government protests and loosening them to hold the elections. In June and July, reformists seeking to challenge Vučić’s tightening grip on power found themselves shoulder to shoulder with radical nationalists and anti-maskers. The leader of the Enough is Enough-Restart reformist-turned-Eurosceptic party, former Minister of the Economy, Saša Radulović, took on the stray rebel role and raved against various globalist conspiracies purportedly behind the “fake” COVID public health crisis.Footnote 9 After protesters stormed parliament in July and clashed with police, the leaders of the reformist, pro-European opposition had to disavow the violent elements as infiltrators and provocateurs and defend themselves against Vučić branding all opposition flat-Earthers and believers in the 5G coronavirus conspiracy.Footnote 10 Vučić’s party went on to win the election in a landslide.

In Croatia, too, Andrej Plenković managed to position his HDZ, the party that invented Croatian clientelism and pioneered state capture, as a pro-European actor competently implementing the scientific consensus approach to managing the COVID crisis. HDZ’s competent management of the first wave brought it its best showing in decades at the July snap parliamentary election, but another party that also won big were the Homeland Movement—a typical stray rebel actor—populist, Eurosceptic, nationalist vehicle for a former folk singer, Miroslav Škoro, who in January 2020 had cost the HDZ the presidency when he split the right-of-center vote with a run alleging corruption in the HDZ. The liberal, pro-European, and traditional anti-corruption MOST party did not have a good showing. March 2021 polls on vaccine intentions reveal the emergence of a conspiracy cleavage in the anti-HDZ vote—while 59% of HDZ supporters are ready to get vaccinated, the figure is almost half for the liberal MOST supporters (37%) and even lower for Škoro’s Eurosceptic nationalists (27%).Footnote 11

The clearest illustration of the rising salience of the conspiracy cleavage comes from Romania. In the December 2020 parliamentary election, the parties of two of Romania’s long-standing pro-European liberal reformers, former prime minister Popescu-Tăriceanu’s ALDE and former president Băsescu’s PMP, failed to clear the 5% threshold. Both politicians are associated with the heyday of Romania’s anti-corruption crusading specialized prosecution (the DNA) and its blows on shadowy oligarchs. Instead, the breakthrough success story of the 2020 parliamentary election was the newly-formed AUR party, which attacked the mainstream PNL and PSD as corrupt, but also traded in all the leading conspiracies. They have attacked Soros, alleged an EU conspiracy to weaken traditional Romanian family values through women’s rights and sexual minority rights, and connected the EU’s latest supposed anti-Romanian conspiracy to a long-standing conspiracy by the Great Powers to hurt Romania geo-politically by separating it from its Moldovan brethren.Footnote 12 AUR also attacked the government’s COVID response by denying the seriousness of the public health threat and promoting anti-masking positions.Footnote 13 Not only did AUR manage to attract 9% of the vote with this message, but it swept the bastion of the traditional Romanian “reformist” electorate—the European diaspora vote.

Conclusion

The early and strict lockdowns imposed by most Eastern European governments seemed to pay off as the region came out of the first COVID wave with some of the lowest per capita death and case rates in the world (Kontis et al. Reference Kontis, Bennett, Rashid, Parks, Pearson-Stuttard, Guillot, Asaria, Zhou, Battaglini and Corsetti2020). We argue, however, that what looked like an out-of-character Eastern European success in tackling the first wave, has exacerbated an already existing and pernicious conspiracy cleavage in the post-Communist political competition arena. The negative effects of this conspiracy cleavage on party institutionalization and the fight against political corruption run deeper than the COVID-related executive aggrandizement analysts feared. We argue that the conspiracy cleavage structures political competition along a misleading and democracy-eroding choice. On one side, the parties of state capture and oligarchic networks deny that any conspiracy exists and feign moderation and cooperation with the EU. On the other side, the true reformist opposition that seeks to expose state capture is drowned out by stray rebels who promise to fight state capture, but also promote other, baseless conspiracies, such as geopolitical plots, anti-Semitic tropes, climate change, and COVID-denialism.

The framework we provide helps us redefine the way we think about where post-communist transitions are stuck—and where they have arrived. The democratic backsliding literature has focused on incumbents who destroy democracy by undermining institutions of democratic accountability (primarily media and courts), by attacking political opponents through heavy-handed approaches, or by manipulating and even stealing elections (Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018; Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016). We propose a new lens through which to understand what ails democracies—how do voters know what they need to know? Put simply, how can the voters become persuaded that there is one conspiracy, that of a governing elite stealing, and a specific alternative of a one or more parties committed to stopping this? Believing that “everything is a conspiracy” is as unhelpful as believing that all is well and the result is a situation of state-capture as durable as it is ostensibly unstable. We call for due attention to the party system and voter behavior markers that explain the political power of conspiratorial beliefs. Our approach thus eschews the teleological bias of the backsliding concept, which has led some to argue that democratic backsliding paints as flawed a picture of democracy’s struggles in the 2010s as transition did of the 1990s processes (Cianetti and Hanley Reference Cianetti and Hanley2021).

Lack of media freedom and a corrupt, politicized judiciary are enabling factors for this new ecology of conspiratorially minded oppositions. Attention to the media and the judiciary is important, but so is attention to the conspiratorial axis where new authoritarian movements emerge. Measurement-wise, we need to find a way of probing not simply people’s beliefs in the appropriate limits of government authority but also their belief in real and imagined conspiracies. The connection between authoritarian thinking and action should be further fleshed out.

There is no doubt that Eastern Europe has many disillusioned voters. A natural expectation would be that to maintain their power, incumbents would tighten the screws by eroding freedoms. Yet state captors have other ways of dead-ending the protest vote. Conspiracy-promotion, made easier by the pandemic, splits the anti-establishment vote. The problem then is not lack of freedom—but too much freedom, as nothing is anchored any more. Incumbents could even relax some of the restrictions on media freedoms, to please the Biden administration or to get the EU off their backs. The net effect will still not be a victory for democracy as the freer media trades in various conspiracies.

The importance of figures like Trump (affection for whom also tracks the authoritarian scale) is also significant. As someone who has successfully won against the establishment, he becomes a natural figure that stray rebels the world over set their compasses by. The change of power in Washington seems to have brought an important appreciation of where the transition in Eastern Europe has stalled, with the chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations offering U.S. support for Bulgaria “in tackling corruption, restoring an independent media, and promoting the rule of law” in a statement on March 4, 2021, implying the relationship between the two countries depends on these long-standing failures of Bulgarian democracy. Recent activity in the EU Parliament toward isolating the party of Orbán, especially if coupled with a more muscular reaction by Germany, and others can only help.

The practical importance of outsiders cannot be overstated. The rise of populism in powerful Western democracies provided an inspiration for many of Eastern Europe’s stray rebels. Unfortunately, the EU, as well as its most powerful members, Germany and France, have mostly continued partnering with anti-democratic, corrupt state captors. This gives the reigning conspiracy legitimacy while robbing reformist oppositions of powerful allies abroad. EU policy makes it harder for the reformist opposition to appeal for broader domestic support, which renders the European position of “these are our partners because there is no one better” a self-fulfilling prophecy. It need not be that.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ names are in alphabetical order. They thank Dominika Hajdu for assistance with the GLOBSEC data. They thank Martin Dimitrov, Ivan Chervenkov, Stefan Dechev, Ruzha Smilova, and Maria Arsova for helping in various ways with the project. They benefited greatly from Michael Bernhard’s editorial guidance. The usual disclaimer applies.