The opportunity to serve as president of the American Political Science Association is a great honor; but it is greater still simply to have the chance to pursue a career in political science. I trust most political scientists share my feeling that it is a privilege to do what we do. Nonetheless, it is my duty at this moment to report that our discipline is now facing serious challenges, in no small measure because the larger political world is deeply troubled, in ways that threaten our work and much more. After sketching these challenges, I will offer some ideas on how we can respond to them by pursuing new intellectual and professional partnerships in our research, teaching, and civic engagements. Though we should always be a pluralistic discipline, both our enduring goals and the difficulties of the present make it wise for us to knit our research results together more often to illuminate major political problems more fully. We can also deepen our grasp of current politics through more engagement with those outside of academia. We will then be able to convey still more valuable political knowledge, still more effectively to the broader world.

The American Political Science Association itself is today in excellent condition, with healthy finances, a fine, well-located headquarters, a superb staff, a modernized governing structure, and most importantly, greater and more productive inclusiveness in our membership, organizational units, and programs and activities than ever before. We have many reasons to celebrate the contributions our association and our discipline are making now.

The Challenges of Modern Politics and Modern Academia

However, when we turn to the broader political world, the picture is far gloomier. The most striking feature of global politics today is the rise in many countries of nationalist movements generally claiming to be populist. These movements are often hostile to foreigners and to ethnocultural minorities within their countries. They are also often authoritarian in their policies and practices, in ways that include suppression of academic freedoms, particularly for those who write, teach, and speak about politics. Earlier this year Human Rights Watch warned that China is working to censor and punish its government’s academic critics wherever they speak or write, at home or abroad (Human Rights Watch 2019). Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, an outspoken champion of what he calls “illiberal democracy,” is placing the research institutes of the nation’s Academy of Sciences under direct political control (Zubaşcu Reference Zubaşcu2019). In Turkey, the Erdoğan regime has fired, blacklisted or even imprisoned thousands of professors (Wilson Reference Wilson2019). In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro’s administration is imposing sharp cuts on universities that have hosted dissident events, and it is seeking to eliminate many departments in the social sciences and humanities, in favor of engineering and medicine (Redden Reference Redden2019). The list could long continue, and it would prominently feature political scientists.

Here in the United States, though president Donald J. Trump has embraced dangerously expansive views of executive power and resisted oversight by both Congress and the courts, we do not face comparable threats to academic freedom. But all is far from well. In recent polls, roughly three-quarters of all Republicans indicate that they believe American higher education is going in the wrong direction, largely because they think political expression on campuses is biased against conservative views (Jacschik Reference Jaschik2018; Turnage Reference Turnage2017). President Trump has therefore threatened to deny federal funds to institutions that his officials deem to be curbing free speech, especially by silencing conservative speakers and students (Jaschik Reference Jaschik2019). At the same time, many left-leaning academics are facing mounting political pressures to refrain from provocative statements not just in classrooms but also on social media. Those pressures come from conservative watchdog groups, from institutional donors, and sometimes from higher education administrators as well. Studies show that incidents of suppressing free speech or other forms of discrimination against conservatives are in fact relatively rare on American college campuses; and while a few prominent conservative guest speakers have frequently faced protests, many analysts believe that left-leaning academics, who are admittedly far more numerous, have most often been sanctioned or terminated for political expression (Beauchamp 2018; Sachs Reference Sachs2018; Woesner, Maranto, and Thompson Reference Woesner, Maranto and Thompson2019; cf. Stevens and Haidt Reference Stevens and Haidt2018). Still, the extensive publicity given to controversies over political speech on campuses in recent years has tempted those in charge of many institutions of higher education to give low priority to departments and programs that feature teaching and research about politics.

Often political pressures can most readily be exerted on public institutions, which teach over 73% of the students in higher education in America, while four-year public institutions hand out over 63% of the political science degrees (National Center for Education Statistics n.d.; DataUSA n.d.). So it matters greatly to our discipline when state legislatures, wealthy donors, and parents paying tuition signal that they do not want those institutions to feature political science. We also do not benefit from the trend in higher education to meet today’s difficulties, including rising tuition costs and high student debt, by turning to business executives for administrative leadership experienced in the management techniques of for-profit corporations (Beardsley Reference Beardsley2018). The consequences not only include counterproductive increases in administrative salaries; like too many modern CEOs, these administrators often focus on generating short-term value for the institution. They do so by favoring disciplines that attract large governmental and corporate grants, such as computer science and some STEM fields, as well as more applied programs, rather than liberal arts subjects like political science. They are also often allergic to student protests and controversial faculty members, preferring more docile online student “customers” and contingently employed teachers (Selingo, Chheng and Clark Reference Selingo, Chheng and Clark2017).

To be sure, there are countertrends. Dismayed by the condition of American democracy, many states are restoring civic education requirements to graduate from high school, and some like Florida are now adding civic literacy mandates for higher-education students, extending the requirements to study American governments that other states, including Texas and California, have long had (Cardinali Reference Cardinali2018; Levesque Reference Levesque2018). These policies prompt many institutions to maintain strong political science programs, though they can also heighten efforts to control what political scientists teach. Many higher education institutions are also now trying to show that they are providing valuable outreach to their communities, and sometimes political scientists are seen as doing so.

Nevertheless, in recent years we have seen efforts like those at the University of Tulsa and the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point to consolidate or close down social science and humanities programs, including many in which political scientists teach (Levit Reference Levit2019; Flaherty Reference Flaherty2019); an attempt at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale to roll political science into a new academic Department of Homeland Security; a proposal at the University of Missouri–St. Louis to absorb the political science graduate program into a graduate program confined to public policy (Delaney and Pratt Reference Delaney and Pratt2018); and the now-accomplished absorption of political science into the History and the Criminal Justice departments at North Carolina A&T, with the political science courses taught mostly by adjuncts (Greensboro News and Record Staff 2017).Footnote 1 The examples are not massive in number, but they are real and rising.

They may be reinforced in the future by the decisions of the National Science Foundation to modify a number of the programs in its Social, Behavioral, and Economics directorate. Its plans include replacing its political science program with two programs, one focused on security and preparedness, the other on accountable institutions and behavior. Its officials hope that funding for political science will now increase; but the NSF is making these changes because they see political science as a toxic brand that harms funding for all the social sciences. If and when these changes are completed, political science will be the only social science that does not have its name as part of any NSF faculty research program (National Science Foundation 2019).

From the point of view of political science, politically and financially motivated curbs on academic freedom and funding for our discipline and allied programs are clearly bad. Most if not all political scientists would also agree that the rise of authoritarian regimes hostile to intellectual and political freedoms is bad for most of humanity. But the forces driving these developments are strong and deeply rooted. They not only include efforts to make academic institutions resemble for-profit corporations more closely, or in many lands, to make them subservient to the regime’s rulers. Perhaps even worse, often these forces include popular resentments toward academia, seen as a realm of privileged, self-centered intellectual elites who are condescending toward, or worse, ignorant of the perspectives and values of many of the mass publics we claim to study and serve.

With these deeply concerning trends in global governance, in attitudes toward higher education in general, and in support for political science in particular, the hard question arises: what good can political science do, to protect our own interests, and to contribute to a better path for global politics? How we can better display our value in increasingly hostile political climates, and still more importantly, how can we generate more value that helps improve those climates?

The State of Political Science Today

Answers must come from an understanding of where we are as a discipline—what our goals are, what our methods are, what our strengths and limitations are, and why we are the way we are. My observations on these topics arise from four decades in the discipline and some study of our history, including past APSA presidential addresses. Several APSA presidents have noted that political scientists seek to learn about politics in part because we just get aesthetic pleasure from doing so (Huntington Reference Huntington1987, 3; Putnam Reference Putnam2003, 249; Katznelson Reference Katznelson2007, 4; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2014, 8). Virtually all have also suggested, however, that we seek to do good through our work, by communicating knowledge that can help people better govern their societies and their world. We seek to do so chiefly through exploring sources and solutions for political problems, and through civic education.Footnote 2

Those goals have always commanded wide assent; but our modern pursuit of them has been profoundly shaped by what remains the major turning point in the history of American political science, the behavioral movement that gained predominance in the 1950s. It shifted the discipline’s center of gravity from description and evaluation of formal governmental institutions, informed by political philosophy, toward quantitative analyses using observed data measurements to test modest generalizations about human behavior, within and across societies and time periods. In 1958 V. O. Key depicted this shift most clearly, while expressing concern about mounting antagonisms between those doing normative political theory and those doing empirical behavioral work. He thought those endeavors ultimately needed each other, but he had no formula for staying their divergence (Key Reference Key1958, 967-968).

Periodically in ensuing decades, other APSA presidents openly worried about the growing fragmentation of the discipline (e.g., Redford Reference Redford1961, 757-58; Truman Reference Truman1965, 869-873; Leiserson Reference Leiserson1975, 181-82; Miller Reference Miller1981, 9-10; Pye Reference Pye1990, 3-4). For a brief time in the 1960s, great figures like Truman, Almond, and Easton hoped political science could unite around the analysis of groups in relation to the inputs and outputs, or structures and functions, of systems (Truman Reference Truman1965, 869-870; Almond Reference Almond1966, 875-879; Easton Reference Easton1969, 1058-1061). Later two disciplinary giants, Warren Miller and Elinor Ostrom, each argued that political science should unify by pooling most if not all of our methods in collaborative endeavors to address large substantive issues, understood by Ostrom to be fundamentally collective action problems (Miller Reference Miller1981, 9-15; Ostrom Reference Ostrom1998, 2-3, 16-17). Other APSA presidents have chosen to provide examples of how drawing insights from different subfields and methodological schools can be the best way to address major political questions (e.g., Pye Reference Pye1990; Keohane Reference Keohane2001; Jervis Reference Jervis2002; Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein2010). Still others have simply championed disciplinary pluralism, highlighting the diversity of the profession’s contributions while stressing the intellectual costs of only doing conventional behavioral studies (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1982; Fenno Reference Fenno1986; Holden Reference Holden2000; Rudolph Reference Rudolph2005). In recent decades, several have particularly criticized the discipline’s limited treatment of often-intertwined issues of class and race (Barker Reference Barker1994; Pinderhughes Reference Pinderhughes2009; Hero Reference Hero2016). And since the 1960s, a number of APSA presidents have worried that the goal of methodological rigor was being given undue priority over exploration of large, important questions. They suggested this imbalance contributed to the discipline’s embarrassing slowness to recognize major developments like the civil rights and protests movements of the 1950s and 60s, the burgeoning of religious conservatism in the 1970s and 80s, and the deepening popular distrust of establishment leaders in the late twentieth century that fueled recent populist uprisings (Redford Reference Redford1961, 757-762; Easton Reference Easton1969, 1057; Lowi Reference Lowi1992, 3-6; Barker Reference Barker1994, 10-12; Holden Reference Holden2000, 2-6; Putnam Reference Putnam2003, 250-52; Katznelson Reference Katznelson2007, 10-12; Pinderhughes Reference Pinderhughes2009, 7-8).

In so arguing, Robert Putnam noted in 2002 that, even as the discipline has made intellectual progress overall, it has swung historically between periods of “scientism” and “activism.” He contended that we must always pursue both (Putnam Reference Putnam2003, 250-51). Though Putnam read a younger Rogers Smith as a dissenting voice, I have always wholeheartedly agreed with the formulation at which he arrived: that “More precise is better,” but still, “Better an approximate answer to an important question than an exact answer to a trivial question” (252). Putnam worried that “the salience” of answering large questions had “dimmed” in the profession over time, but he saw the tide turning toward ardent pursuit of both (251).

In many respects, our discipline is indeed striking a better balance today. Consider, for example, one of the greatest issues in modern America, the rise of staggering levels of economic inequality over the past generation. Political scientists like Larry Bartels, Martin Gilens, and Gordon Lafer have used both quantitative and qualitative techniques, mapping both outcomes and mechanisms, to show indisputably that policy-makers at the national and state levels have given and are giving the wealthy the inegalitarian policies they want, instead of heeding the policy preferences of the great majority of Americans (Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Lafer Reference Lafer2017). Many political scientists are wrestling productively with the implications of this reality for democracy, for popular resentments, and for environmental as well as economic policies, among others. Many more contributions could be listed.

But in light of the great challenges we and the world face today, we must focus instead on how to do still more. We are held back by at least three factors. The first is the sheer intellectual difficulty of our work. Political science is not rocket science. It’s harder. Human political behavior is shaped by so many variables that it is hard to find regularities with much specificity that hold across much time or space (Pye Reference Pye1990, 4). Elite gift-giving that is seen as obligatory or even saintly in one society or era may be deemed insulting or corrupt in another (Hann Reference Hann, Christoph-Kolm and Ythier2006). We also cannot ignore the great complexities introduced by the fact that, unlike rockets, our subjects’ interpretations of our research findings may alter their behavior, as in the impact of “broken glass” theories of crime on law enforcement policies (Hinkle and Weisburd Reference Hinkle and Weisburd2008). And we will probably always struggle with the great mystery of how far human political agency is determined by external variables, and insofar as it is not, whether it can be fully explained at all.

Faced with these difficulties, it is understandable that we often focus on smaller, more tractable empirical questions, hoping that we will accumulate over time a body of reliable empirical findings that may equip us to engage grander topics and do larger theorizing down the road. But if smaller studies are all we attempt—if, far more than the natural sciences, we postpone seeking to combine these studies to address major problems––we cannot be surprised when many who pay our bills complain that we consign everything they most care about to our constant calls for further research.

The second, equally profound factor holding us back is that, as Charles Lindblom argued in his 1981 presidential address, it is difficult to recognize, much less escape, assumptions in our political thinking that are shaped by the dominant institutions, practices, and norms in our own societies—all the more so when potent forces in those societies seem prepared to act against any questioning of the arrangements that benefit and empower them (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1982, Reference Lindblom1990; see also Easton Reference Easton1969, 1057-58; Holden Reference Holden2000, 4-5; Rudolph Reference Rudolph2005, 5-9). Both our internal cognitive and psychological limitations and external political pressures can lead us not to reflect on premises that, if reconsidered, might help us see better why the political world does not always work in ways suggested by conventional assumptions. So we always need to build appropriate forms of assumption-questioning into our disciplinary work, as much as we can.Footnote 3

The third, more mundane but still crucial factor constraining us is that we do our professional labors within modern market systems and institutions that reward many kinds of work––but they reward some kinds more readily than others. Like scholars in other disciplines, we political scientists share a profession, but we work in departments, programs, and higher-education institutions that compete with each other. That competition can spur excellence, but again, in some respects more than others.

To win prestige and attract resources, many institutions want highly ranked departments and programs. For the same reasons, many political scientists want to be in highly ranked departments, programs, and institutions. Rankings today are based extensively on the quantity and quality of faculty research publications, which administrators, especially today’s CEO-style administrators, sometimes judge largely through citation counts, and through numbers of publications in journals that are ranked highly, often because of their citation counts. Scholars are also evaluated, to be sure, by peers in published reviews and confidential letters, and these assessments go well beyond counting exercises. Still, the linkage of rankings to frequently published and widely cited research gives scholars incentives to undertake projects that carve out from large topics sets of narrower questions favored by subfield literatures—questions that can be settled relatively definitively by standard quantitative methods. These projects have a greater likelihood than others of generating a series of articles, sometimes deemed “minimal publishable units,” that will appear in well-ranked places and gain citations from others pursuing similar scholarly agendas in similar venues. Our current academic markets do not encourage scholars to seek to integrate their work in any systematic way with those researching different dimensions of large topics, especially those doing so using different methods.

There is nothing malicious about this. Much of this research makes valuable intellectual contributions. It is also easy to overstate the impacts of market forces: the roster of recent APSA officers and award winners suffices to show that our discipline not only contains but often rewards scholarship that is richly diverse, in methods, substance, and authorship. Even so, our academic market systems do create pressures, especially for younger scholars, to do research that primarily addresses narrower, more technical, and more conventional questions, which may or may not eventually shed light on larger topics of general interest.

Even when our work does illuminate such larger topics, moreover, the writing habits borne of efforts to impress disciplinary journal referees often obstruct communicating our insights to wider audiences. The political scientists at the National Science Foundation strongly believe that many in our discipline are doing outstanding scholarship. But even in writing grant applications, we too often present our research as seeking to fill gaps in our insular literatures. Or we can seem only to offer technical advice on tactics to party operatives, legislators, or other officials. Those endeavors have worth; but we often fail to make clear to broader audiences that we are focused on major problems that they are experiencing, or on issues that they can come to see as of vital importance to them. So, what many of us find beautifully rigorous, many outsiders find hopelessly arcane.

Our profession is also shaped by the fact that institutions pursuing high rankings, particularly those that are already wealthy and prestigious, often place only minor emphasis on teaching––because it is less visible, and because we have few rigorous means to assess effective teaching, especially in its long-run impacts. The renewed support today for civic education suggests that even so, many in the public value our teaching more than our research. We alienate supporters when fees go higher and higher while professors teach less and less.

Similarly, many universities define service simply as work within the institution to support its research and teaching, not direct constructive engagement with the wider world. Such civic engagement may instead be dismissed as dereliction from academic duties. As a result, some political scientists contend that our academic markets fail to assign suitable value to publicly useful research and service that do not appear in major disciplinary journals, a tendency only partly offset by reliance on Google Scholar counts to evaluate scholarly standing (Campbell and Desch Reference Campbell and Desch2018; Peress Reference Peress2019, 314). Others, including political scientists in Europe, where governmentally mandated research metrics often loom even larger, argue that the main current metrics not only militate against relevance in political science scholarship, paradoxically in the name of social accountability; the research metrics also discourage attention to teaching (Piattoni Reference Piattoni2017).

These aspects of modern academic life may be rendering our discipline less able to do good through either our teaching or our research. They can hinder how deeply and fully we explore the major developments of our time, including the rising political tide hostile to academic freedoms. They can hamper us as we try to persuade the growing numbers who doubt our worth. In an important analysis of contemporary higher education, sociologist Steven Brint notes that research funding and enrollments in America’s universities and colleges are very high. But he documents mounting dissatisfactions with academia; and he contends that to address them, we need to do a better job of connecting with––without becoming subservient to––the external actors whom we claim to aid and whose support we seek. We also need to focus more on improving teaching to enhance student learning, which by some measures is declining (Brint Reference Brint2018, 12-18).

Though in political science valuable initiatives have long been underway to do all these things, the state of our discipline makes progress hard. We are and must be characterized by a pluralism that includes not only divides over methods and substantive interests, but also a great variety of higher education institutions and missions, as well as a wide range of identity groups. It is not clear how we can get it together to partner with each other in facing the political and professional challenges of our time. But fools rush in, so here are my ideas.

The Foundational Value of Intellectual Honesty

We should begin with the cornerstone value of all academic work: intellectual honesty. It is the life-sustaining heart of all valid methods of inquiry. There simply is no way to pursue real knowledge without being honest, at least with ourselves, about precisely what hypotheses, claims, and arguments we are seeking to advance; what count as evidence and reasons for and against those claims; and whether we have done all we can to collect and weigh systematically all such evidence, and to think through alternative accounts. To be sure, as Arthur Melzer has shown, scholars of politics have always faced special ethical questions about how fully they seek to communicate the results of their political inquiries. Scholars may well risk harsh political reprisals against themselves and those with whom they have worked, and they may judge that publicity for their findings will work against achieving desirable political outcomes (Melzer Reference Melzer2014).

Those worries are far from past, nor are they confined to scholars working in authoritarian regimes. Jennifer Hochschild considered abandoning her study of how commitments to democracy threatened court-ordered racial desegregation, because she worried about discrediting either democracy or desegregation or both (Hochschild 1984). Robert Putnam debated delivering and publishing his Skytte Prize Lecture because of its evidence that demographic diversity could erode social capital (Putnam Reference Putnam2007). Peter Singer and others are founding a Journal of Controversial Ideas in which authors can publish under pseudonyms, since writers on incendiary issues like abortion have received death threats (Flaherty Reference Flaherty2018). Yet while we have real concerns over how we communicate our work, I believe that even those who doubt the possibility and desirability of disinterested “objectivity,” as I do, still recognize that to gain insights, we must be as honest as we can with ourselves and our peers about the sources and evidence for––and the biases and limitations of––our views. The quest to be intellectually honest so that we can truly learn may in fact be the only commitment that all political scientists and all in academia share.

Even so, we often fail to live up to it. In recent years, beginning in social psychology, all the social sciences have struggled with the recognition that many influential published studies have not proven replicable (Meyer and Chabris Reference Meyer and Chabris2014; O’Grady Reference O’Grady2018). Some believe the reasons go back to publishing pressures: because editors love statistically significant counter-intuitive findings, and because so many judgment calls go into data cleaning, imputation of missing variables, choices of statistical models, significance measures, outcomes to report, and other steps in quantitative research, even well-intended scholars may end up presenting exciting “findings” that similar studies fail to reach. And cases of deliberate cherry-picking of results, P-hacking, outright forgery of data, plagiarism, and other abuses do occur, in ways that even conscientious colleagues can miss.

We can take pride in the fact that our discipline has actively sought to address these problems in recent years. Even before anxieties about non-replicable results heightened, many quantitative political scientists began to face up to long-minimized issues of omitted variables and other weaknesses in observational research by pioneering innovative randomized field experiments. The contributions of this experimental turn are undeniable, though major debates persist over how far it solves all the methodological problems, over its ethical dimensions, and over whether an excessive emphasis on experiments will unduly constrict the questions political scientists ask (Teele Reference Teele2014). More recently, both quantitative and qualitative scholars have sought to promote replicability and intellectual honesty in research by encouraging scholars and journals to make complete data sets available online; by posting research designs before results are reached; by employing more demanding tests of statistical significance; by working collaboratively to conduct identical experiments in different locations; and by rewarding reporting of null findings, among many other steps (Lupia and Elman Reference Lupia and Elman2014; Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Grossman, Humphreys, Hyde, McIntosh and Nellis2019).

These initiatives, too, raise important questions that have been usefully explored in the Quality Transparency Deliberations steered by Tim Büthe and Alan Jacobs (APSA Section for Qualitative and Multi-Methods Research 2019). The issues include whether transparency initiatives will disadvantage publication of some kinds of valuable scholarship, including studies using confidential interviews in authoritarian regimes; research on vulnerable and marginalized groups whose privacy may need protection in all societies; and ethnographies, where researchers strive to develop their categories of analysis from the perspectives of their subjects as much as possible, among others. Scholars who do such work, who are often themselves members of marginalized groups, may be similarly disadvantaged. As a discipline we must work collectively to address these vital issues, recognizing that whatever our methods or interests, we share commitments and obligations to do research in ways that are as intellectually honest and rigorous as possible, and as dedicated to forming and answering important questions as possible.

Disciplinary Responsibilities

There are other regards in which our discipline can do still more to live up to the full demands of intellectual honesty, in ways that can better equip us to meet today’s political and professional challenges. We claim that our discipline as a whole strives to achieve and communicate “findings on important theoretical and political issues,” as APSA’s current Strategic Plan puts it (APSA Staff 2019). But the reality is that our pluralism, or more harshly our fragmentation, means that, again in striking contrast to the natural sciences, we rarely strive to synthesize our inquiries to form more comprehensive and cohesive accounts of all we study. And even though we often suggest that our more particular empirical inquiries, taken by themselves, can shed light on larger issues, we too rarely try to show how and why we think that is so. Instead, particularly in the journal articles that do most to boost citation counts, we leave our accounts of why and how the topics of our specific studies are broadly important undeveloped, sometimes even unstated.

The May 2019 American Political Science Review provides examples of how we shape the presentation of research by outstanding young scholars in ways that cloak the contributions of their work to these larger disciplinary commitments. Taylor Carlson’s lab experiments indicate that the political news people receive through social networks differs significantly from that obtained through traditional news media (Carlson Reference Carlson2019). Adam Zelizer’s field experiments with state legislators who share offices with fellow partisans show that, as scholars relying on interviews have long suggested, these lawmakers take cues from those they see as like-minded policy experts in order to decide what positions to take at certain points in legislative processes--rather than simply being self-reliant throughout (Zelizer Reference Zelizer2019).

What is the larger significance of these findings? Both authors give more attention to their implications for scholarly debates about sources of political information and cue-taking processes than they do to how the conduct they depict is likely to shape most people’s lives. Zelizer briefly worries in conclusion that like-minded cue-taking may deepen polarization; Carlson, that social communication may have biases that we need to understand (Zelizer Reference Zelizer2019, 351; Carlson Reference Carlson2019, 338). But, though both do more elsewhere, their APSR pieces stop at these terse suggestions. They do so not only because of practical research and publication limitations, but also because reviewers have told them that their focus should be on the scholarly literature. Consequently, they do not lay out why and how cue-taking and social communications may have consequences that should concern many outside of political science.

When we do make claims for our findings, moreover, we must acknowledge that all our results, whatever our methods, always remain probabilistic and corrigible. This is so in part because, as most modern epistemologies since Quine have argued, all specific findings are always imbedded, at least implicitly, in larger accounts—big pictures of how politics and the world work—which help us judge why specific findings are not only probably true, but also probably of broader empirical and normative significance (Quine and Ullian Reference Quine and Ullian1970). But too often, we barely suggest the elements of the big-picture accounts that show why our work is important beyond academia. These practices mean that while political science scholarship can often claim to have established particular causal or descriptive findings rigorously, often we cannot honestly claim to have elaborated or defended our reasons for regarding them as significant. As a result, many lay readers doubt the importance of our studies and even how much we desire to do important work.

Developing Our Big Pictures: The Spiral of Politics

I therefore suggest that we need to find ways to place our particular studies more explicitly in broader accounts of politics that can credibly indicate their importance. When political scientists study different elements of similar big-picture accounts, moreover, we should attempt systematic syntheses of their arguments more often than we now do. Our research results may then either reinforce each other, enhancing our discipline’s collective contributions, or they may conflict, raising vital questions about those big pictures. And at times, scholars who embrace the same big picture but who work on different dimensions of it with different methods may find they can fruitfully partner with each other, as Miller and Ostrom urged.

The pluralism of our discipline makes it unlikely that we will converge on any single big picture of politics in the foreseeable future. But I doubt we need to do so. We simply must make more explicit, and in the process clearer and more precise, the big pictures with which we are already tacitly operating. To give an example––though it is just one example––of what I mean by a big picture: a few years ago I proposed that we try to capture the broader significance of political developments by presenting them as parts of what I call “spirals of politics” (Smith Reference Smith2015, 19-35). While this proposal was primarily directed to my fellow historical institutionalists, it is not confined to them, since all political behaviors occur within historical sequences.

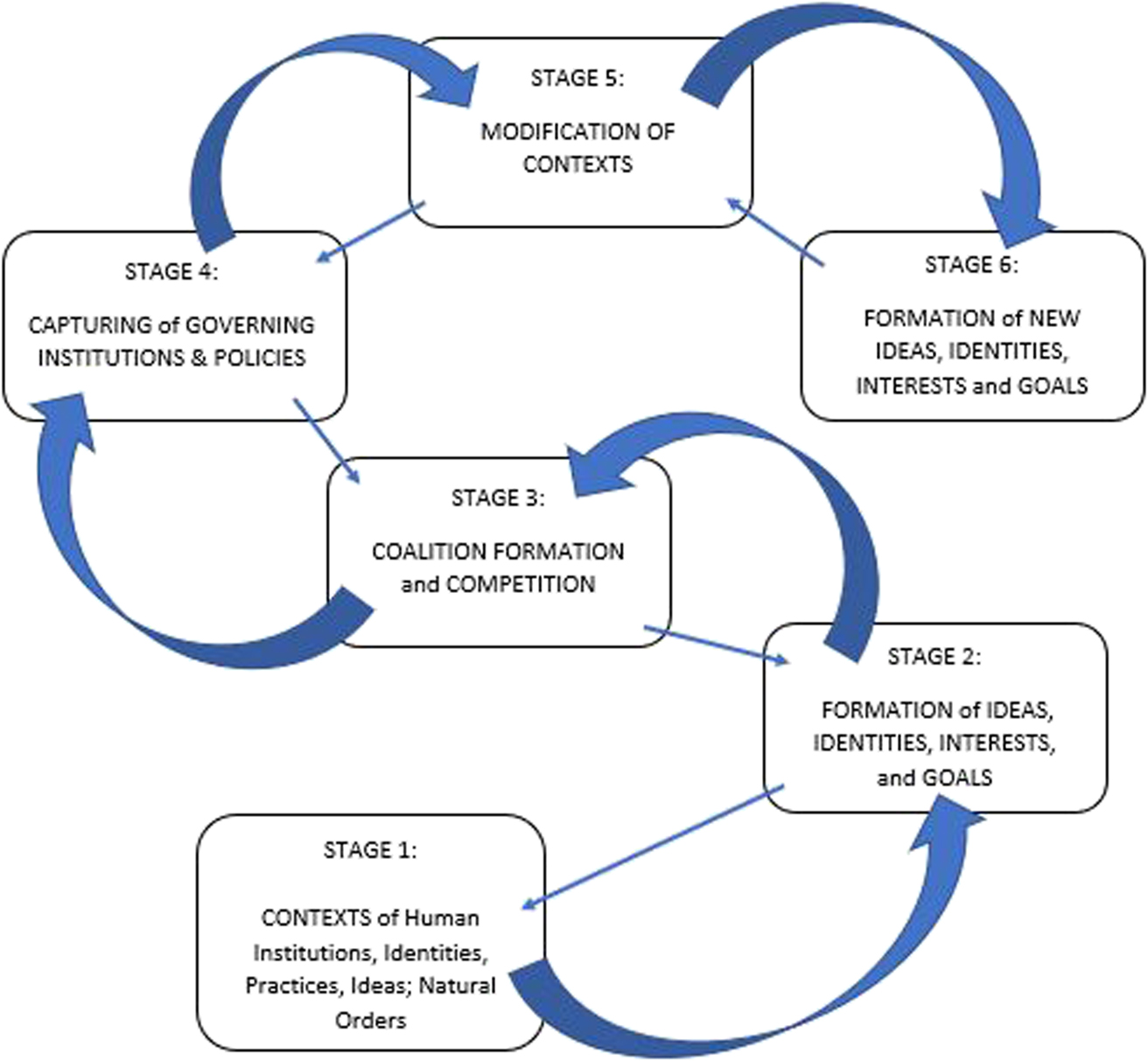

As shown in figure 1, spirals of politics depict the stages through which political developments typically occur. Political phenomena always arise out of sets of pre-existing human and natural contexts. These include arrays of political, economic, and social institutions, associations and practices; senses of human identities; and ideas about how to live, all taking place in physical environments with evolving features. These contexts comprise Stage 1 of any spiral of interest; and we are generally interested in them because at least some of the people living in those contexts respond to them with political action. Their circumstances may lead them to feel dissatisfied with how and by whom they and others are being governed. Those feelings often spur fresh political thinking and behavior.

Figure 1 The spiral of politics

The thinking frequently includes people reconsidering what their political interests are, even what their political identities should be, as partisans, as social movement activists, as communities facing threats, and more; and so some may decide on new political goals and strategies. These emerging ideas, identities, goals and strategies comprise Stage 2. Stage 3 occurs when those with new or newly mobilized senses of political identity and purpose form coalitions with others who have overlapping interests and goals. These coalitions then compete with rival ones. The coalitions clash either in electoral contests, which may be more or less formal, free and fair, or via force. Either way, those clashes generally enable one coalition to gain power over most existing governing institutions, or to create new ones, in order to implement the policies to achieve their purposes. Those institutional and policy innovations constitute Stage 4. Often the new policies and institutions prove to have unintended consequences; but whether intended or not, the defining feature of Stage 5 is that these changes in governance reshape many of the political, economic, social, and the physical contexts that comprised Stage 1. The modified contexts of Stage 5 then sooner or later give rise in Stage 6 to the formation of new ideas, identities, interests, goals, and political actions, as this spiral of politics continues, following the same basic stages, but with altered content.

The model does not assume that these alterations are improvements; political life can spiral down as well as up, and it can just go sideways. Nor is there any guarantee that the victories won in Stage 3 will be permanent. As political spirals continue, the losers now may be later to win. But the spiral model does accept that any specific change gets much of its significance from its place in larger developmental sequences. To be sure, as indicated by the thinner lines pointing backwards in figure 1, not all changes occur in the main directions shown on a particular spiral. The tasks of coalition formation and of effective governance are especially likely to foster some circling back, some reconsideration of the goals and even the senses of identity of many actors. Still, most political behaviors can be usefully mapped as occurring along such a spiral. Indeed, I suspect that most of us imagine whatever political phenomena we are studying as playing roles in the kinds of developmental paths that spirals depict.

We may, however, rely on other kinds of big-picture accounts. One strength of the spiral of politics model is that it can be readily synthesized with many other big-picture accounts that make more specific claims. These include Marxist analyses privileging class struggles; views depicting politics as driven by individual economic interests; portraits of politics as contests among social groups; histories that trace stages of human development to technological or ideological innovations; culture-centered accounts that see politics as at bottom clashing civilizations; and many more. Scholars whose work presumes the validity of one of these accounts may, however, choose to invoke them without referring to the spiral of politics or any similar model. My argument is not for historical institutionalism; it is simply for making our big pictures more explicit.

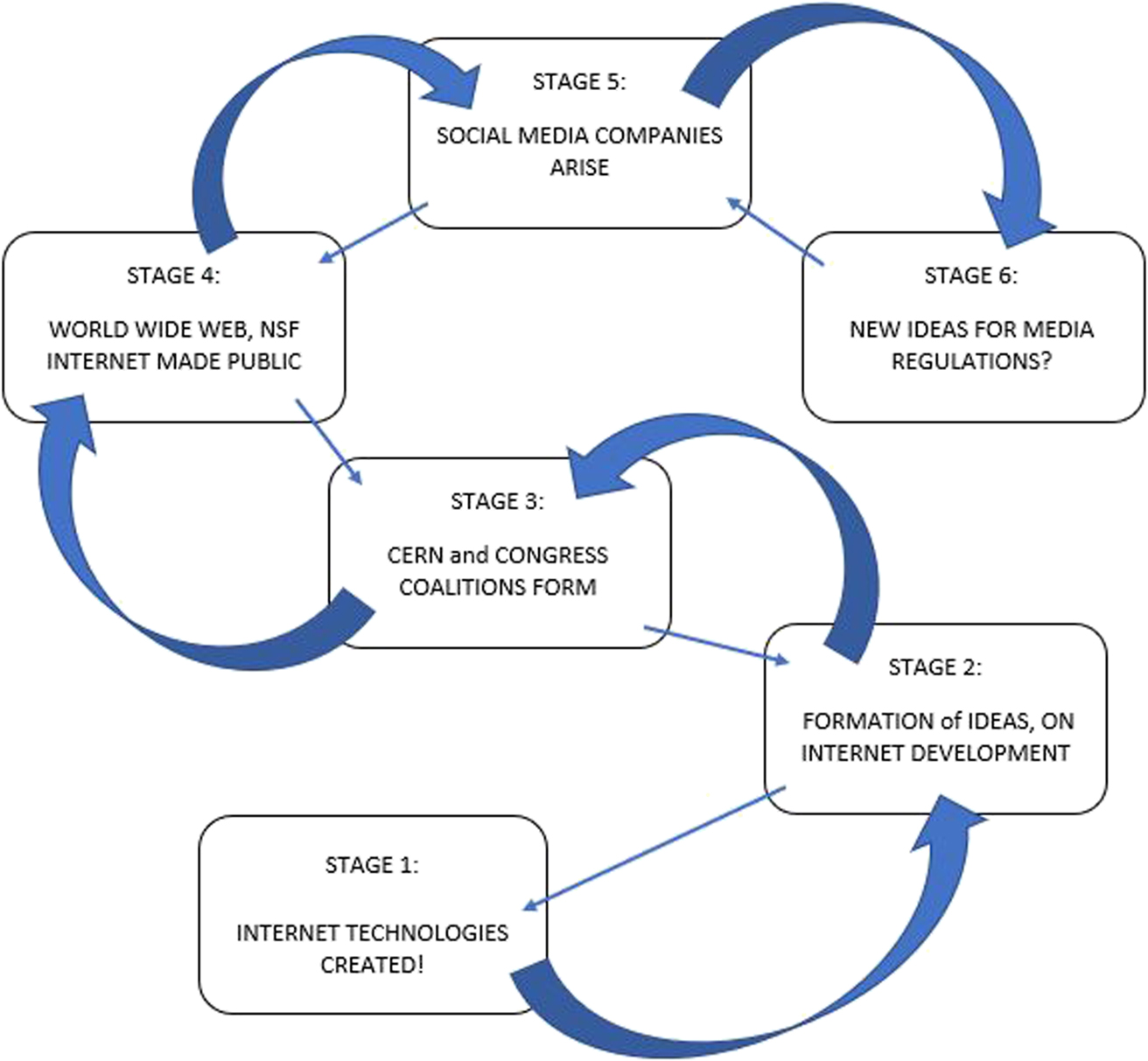

What would doing so involve? Continuing to use the spiral model, take Carlson’s work on social media as an example, shown in Figure 2. If we treat 1990 as Stage 1, in that year today’s social media did not exist. But novel internet technologies did, and scientific, economic, and political actors were rapidly forming and debating ideas about how to put them to broader public use: Stage 2. In 1991, CERN, the European research consortium sponsored by a number of governments, made its World Wide Web technology freely available to all (CERN 2019). In 1992, the U.S. Congress passed the Scientific and Advanced Technology Act, permitting the NSF’s internet to connect with commercial networks. In ensuing years entrepreneurs used the web to create social-media companies (The Web n.d.). They were subject to different regulatory regimes in different areas of the world that sometimes altered the decisions taking by CERN and Congress. These political processes comprised Stages 3 and 4. Those developments produced a modern Stage 5 in which contexts of communications are greatly different than in 1990, with persons receiving significantly varied political news through social media in contrast to traditional media, as Carlson shows.

Figure 2 The spiral of politics and social media

Carlson could not have documented the stages of this spiral in detail in her article. But a brief sketch of them might have served three valuable purposes. First, it would help readers understand how politics partly generated the phenomena she studies—and it is surely the distinctive responsibility of political science to explore how politics has shaped the world. Second, it would help other political scientists consider how her findings fit with, challenge, or are challenged by their works on related topics, perhaps transnational organizations or neoliberal regulatory regimes or free speech norms. And third, placing her results in this bigger political picture might make it instantly clear to general readers why the rise of social media conveying distinctive political information is not just intellectually interesting. It also presents people with significant political choices about whether to continue the policies that have helped create the current moment, and its difficulties, or to choose a different regulatory path.

Similarly, Zelizer’s findings on how state legislators rely on cues from fellow partisans might be placed in a spiral suggesting how and why state governments have assumed more and more diverse responsibilities over time, and how and why American political parties have become more ideologically homogeneous, and more sharply polarized, over time. But he might prefer to invoke a different big picture, perhaps one focused on individual and institutional decision-making as the basic building blocks of political life. Whatever big picture he invoked could amplify the relevance of his findings to general readers and suggest how they relate to the works of other scholars—perhaps including Carlson, since the rise of social media may well contribute to partisan polarization.

Admittedly, at present my advice poses risks. If a scholar suggests how a study’s findings fit into a more sweeping account of politics that the author cannot document within the scope of a particular paper, some journal reviewers, editors, and readers might find the big picture invoked unpersuasive and reject the paper. Others might be convinced the big picture matters, but not that the reported finding adds much to it. Yet while those risks are real, our discipline as a whole will fall short of our goals if we socialize authors to keep hidden assumptions and contentions that are vital to the broader significance of their work. We are far more likely to strengthen our individual scholarly products, to discern opportunities for productive intellectual partnerships, and to live up to what we profess to be our aims, if we feel obliged to bring into view the broader pictures where we place our results. We will also be more able to persuade skeptics why and how our studies matter for many people’s lives.

What about V.O. Key’s worry that political philosophy, including the history of political ideas and normative, analytical, and critical political theory, cannot easily reside under the same disciplinary roof as our variety of empirical researchers? Here too, recognizing the role of big pictures is beneficial. After all, many political theorists of all stripes advance, more or less elaborately, just such big pictures. Most behavioral scholarship presumes the general veracity of one big picture or another, whether it is the group pluralism of Bentley, Truman, and Dahl; the neoclassical economists’ world of individual rational choices; or left-leaning accounts of class hegemony. But those big pictures are all debatable. Theorists offer rival accounts that can suggest lines of empirical inquiry which may strengthen or weaken the empirical and normative credibility of current behavioral big pictures, as well as those advanced by canonical figures from Plato and Machiavelli to Fanon and Foucault. Within modern political science, theorists like Walzer, Connolly, Mansbridge, Fraser, and others have provided pictures of politics that can help researchers formulate vital questions about the limits of pluralism, the politics of negotiation, the sources of political resentment, and more.

Exploring sharply different political philosophies can especially help us recognize the unexamined presumptions that may be shaping and limiting our theoretical and empirical work, even as that research usefully challenges empirical and normative assumptions in major theories. A grasp of major works of political theory can also save scholars from reinventing wheels. And because, however timeless their thought may be, all political thinkers lived in particular times and places, understanding their writings in their contexts can help us understand many of the world’s most important historical spirals of politics. Perhaps most importantly, political theorists can also help us imagine alternative political communities and institutions that might better respond to current discontents. Consequently, as much or more than Key, I believe political theory in all its varieties can contribute to, and benefit from, the expanded intellectual partnerships we need.

Steps Forward in Our Research

I turn now to two other ways to strengthen our research contributions that, unlike this call to develop our big pictures, are not exhortations for all political scientists, since we must always study many topics using many methods. They are, however, calls for our discipline to recognize the importance of some kinds of work that we have unduly minimized. One call is substantive, the other is methodological.

Political Identities

The substantive call is to do more research that takes human identities as our dependent variables––as conceptions, categories, classifications, institutions, memberships, and behavioral patterns and performances that are not purely “natural” or extra-political, but are instead significantly constituted by political processes and policies (cf. Brubaker Reference Brubaker2006). There is certainly excellent existing work on which to build in this regard. In the last generation, scholars in many disciplines, including feminist, disability, critical race and queer theorists, have usefully disrupted many older assumptions about identities. For even longer, comparativists in political science have studied racial, ethnic, religious, and nationalist politics, and for decades scholarship conceiving of these identities as constructed has predominated over works depicting them as primordial. Constructivism is also a major if contested school in international relations.

Nonetheless, political science still needs to give the role of politics in forming human identities more prominence, especially in our empirical work. Though it is now common to hold that many identities are intersectional social constructions, often we still model identities as fixed, politically exogenous independent variables that affect matters like voting behavior or senses of political efficacy. As Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels have argued, “the concept of identity” remains “imperfectly integrated into the study of political behavior,” and in particular, the “role of political elites in structuring political relevant” identities and cleavages “needs to be understood better” (Achen and Bartels 2006, 230).

Though I have long made similar arguments, my previous depictions of the spiral of politics failed to highlight how pre-existing identities, which shape conceptions of personal and group interests, values, and goals, are often modified as political spirals proceed. That neglect means my big picture did not sufficiently challenge the deeply embedded tendency of our discipline, and indeed most human thought, to treat the identities we find at any Stage 1 as fundamentally pre-political, as originating in biological or economic or sociological or other systems that are seen as not chiefly products of politics, and as nonetheless driving politics. So let me stress: I believe every Stage 1 is preceded by spirals of politics that have done much to shape all the identities of everyone we find there. Those identities may then operate as independent variables in political processes, but they should not be presumed to be originally pre-political. Instead, we should always entertain the hypothesis that any and all particular identities have been in large measure produced by––and can be reproduced or greatly modified or even eradicated by––political actions over time.

We may decide that identities are most politically significant in their roles as causal variables, and we may conclude that some identities, perhaps class or partisan ones, are most deeply determinative in our lives. Even so, we should not assume away the possibility that all human identities are politically constructed, and I do mean all—racial, ethnic, gendered, sexual, economic, religious, linguistic, cultural, national, regional, familial, and more. Politics not only shapes many identities commonly seen as political, such as party ID and nationality. Its reach also extends to aspects of identity that can appear purely social, such as people’s names and hobbies. Resistance to white domination may help explain why African Americans often choose different spellings for names pronounced similarly to those of European-descended ones. Legacies of conquest and imperialism may help account for why many East Asians play baseball, while many South Asians play cricket. I believe that, more pervasively than we have understood, all people are who they are partly because politics created policies and institutions that defined and favored some identities, while disfavoring and punishing others.

This has been true throughout human history. Even so, we as a discipline have focused on studying politics as “who gets what, when, and how,” in Harold Lasswell’s famous phrase, or on who and what has power over whom. Until recently, the study of how and why politics shapes who people feel they are has not been one of our discipline’s dominant themes. Yet we cannot fully understand who gets what, or who governs whom, if we do not understand who becomes whom––how and why human identities, particularly dominant and subordinate identities, are constructed, sustained, and disputed.

There are many reasons for these failings. Studies of how politics shapes identities can destabilize power structures that scholars may not wish to challenge. Though most white, mainstream American political scientists came in the twentieth century to repudiate the racial theories the discipline featured when it first arose in the late nineteenth century, many chose not to focus on the political construction of racial identities and hierarchies, but instead to neglect racial topics almost entirely (Blatt Reference Blatt2018, 3-4). The near-total absence of racial issues in APSA presidential addresses until the 1960s strikingly supports David Easton’s lament that our discipline largely neglected the rise of the modern civil rights movement and the multiple protest movements it helped to foster—even as he himself neglected the attention to these topics by scholars deemed outside the disciplinary mainstream (Easton Reference Easton1969, 1057).

I suspect that today, many political scientists resist studying the politics of identities because of their aversions to what we now call “identity politics”—forms of politics in which, again, identities are often taken as exogenous causal variables, not as politically generated. Analysts also rightly fear lumping together under one heading political processes of identity formation that differ greatly in their grounding in social reality and in their consequences for human lives. Perhaps most fundamentally, thinking that all human identities may be partly the products of past and present politics can be demoralizing. We may fear that no identities are authentic and that there is nothing in which we can firmly anchor our beliefs about what choices, what values, and what purposes are right for us.

Yet our disciplinary history suggests strongly that we are not going to be able to understand major political developments of the past, present, and future if we do not explore more deeply the politics of identity formation, using all methods that can help. Doing so might help us understand better why many religious believers, not just fossil fuel industry executives, ignore the science supporting climate change; why some worker- and middle-class groups support policies that do not maximize their wealth, and instead heighten their relative inequality; why movements like Black Lives Matter, #metoo, Democratic Socialists, militant Islamic groups, and today’s new nationalisms are all stirring modern politics; and more. These are all topics we need to understand better.

Civically Engaged Research

Toward that same end, I suggest we must also make more prominent a certain set of methods: those involved in what is now often called “civically engaged research.” By this I mean research that is done through significant immersion in, and ideally in respectful partnerships with social groups, organizations, and governmental bodies, in ways that shape both our research questions and our investigations of answers.Footnote 4 Those last points are vital. Civically engaged research is not simply field work. It does not focus on taking survey instruments and experimental designs constructed with our internal disciplinary debates chiefly in view and then going to remote locales to administer them, instead of just using our students as research subjects. Our discipline needs such field work; but we also need research in which scholars listen to their partner groups and organizations when deciding what to study, how to study, and what answers are convincing and helpful.

Some modern scholars reject calls for such research as summons to pick up the John Dewey-eyed vision of progressive reformers. These critics fear we will sacrifice what they call scientific objectivity, and what I call intellectual honesty, for service to political causes, usually left-leaning ones. But to conduct civically engaged research well, scholars must use appropriate social science methods, and they also must not suspend all critical judgment toward those with whom they work. Civically engaged research must genuinely aim at achieving deeper understanding of public problems, while also helping to solve some of them, with the learning coming in part through the helping. But civically engaged research always involves ethical questions about how far researchers should accept and assist the goals of those with whom they work. In the recent Metaketa Initiative, for example, study teams sought to partner with local NGOs and government offices in six countries when designing as well as implementing broadly similar interventions in voter information. They commendably strove to design research that could advance cumulative learning, while also addressing the concerns of their civic research partners. If, however, such studies were to involve spreading misinformation that aided a partner organization in local political contests, it would represent unethical cooptation, not intellectually honest research.

But though the ethical and intellectual dangers are real, and though we political scientists are already sometimes perceived as too activist, since the behavioral revolution we have probably done too little civically engaged research, rather than too much. The work we have done has also been skewed toward groups with which political scientists have strong ideological and demographic affinities. Though such rapport can be productive, as a discipline we must learn from all segments of our societies. If more of us had been attending more closely to the diversity of African American organizers in the 1950s and 60s, to increasingly fearful fundamentalists as well as increasingly confident LGBTQ advocates in the 1970s, and to angry workers in deindustrializing and rural regions earlier in the twenty-first century, we might have perceived sooner what was happening in some of the most central arenas of American life. We might have grasped better why new civil rights goals and also a new Religious Right arose, why LGBTQ rights progressed despite mounting electoral victories for conservative politicians, and why nationalist and nativist forms of populism are resurgent today, among other matters.

It is also possible that, if more of us had actively worked with all these groups to help them address their concerns in ethically defensible ways, then black communities, conservative religious groups, gay activists, and workers and farmers might feel less suspicion and disdain toward academia in general and political science in particular than many do in the United States today. The same may be true in many other parts of the world. Intellectual honesty means I cannot guarantee you that more civically engaged research would have helped us do better in all these regards. But I know that we did not do much, and in light of where our politics is now and where our profession is now, it is worth trying to do more in the future.

Steps Forward in Our Professional Life

APSA Initiatives

All these arguments form part of the case for a range of professional initiatives that many political scientists, including many APSA elected leaders and staff, have already undertaken in recent years. As detailed at apsanet.org, we now have standing Council Policy Committees working on public engagement and on teaching and learning, as well as on membership and professional development and publications. We have new Status Committees that recognize the importance of community colleges, contingent faculty, and first generation academics and that seek to address their needs. We have a journal devoted to political science education and more panels and workshops devoted to pedagogy at our conferences and at APSA headquarters. We have issued reports on improving how our discipline communicates its public value and on strengthening civic education, as well as studies on the persistence and deepening of many kinds of inequality, in our profession and in the larger world, with strategies for addressing them.

Building on all this work, my presidential Task Force on New Partnerships, made up of a diverse range of exceptionally able political scientists and chaired by Robert Lieberman, initiated new Research Partnerships on Critical Issues, beginning with a Congress Reform project led by Frances Lee and Eric Schickler and conducted in alliance with two think tanks, the Brookings Institution and the R Street Institute. The Task force also launched new pedagogical partnerships between research-intensive and teaching-intensive institutions, as well as an online APSA teaching library; and it has established a new APSA summer Institute on Civically Engaged Research, along with an APSA award recognizing distinguished civically engaged scholarship. In addition, the Task Force has sponsored a Public Scholars program that funds graduate students to translate political science journal articles into brief, accessible summaries to aid public understanding and teaching (APSA Centennial Center 2019).

Journal Priorities

We cannot, however, hope to strengthen our profession’s capacities to do good for ourselves and others primarily through top-down initiatives. We must change some of the ways we run our journals, our departments, and our classrooms. Journal editors and reviewers must always strive to insure the intellectual honesty and rigor of our research. But to fulfill our promise to present important findings, we should discourage only writing minimal publishable units and encourage sometimes striving for maximally significant units. To do so, publication policies must not disadvantage synthesizing accounts, or works that use confidential sources, or work that is done collaboratively with non-academics, or inductive projects that suggest new possibilities, even as we continue to improve causal testing. We need it all.

Department Priorities: Substance and Teaching

My final suggestion may seem still more unsettling. In light of both our highest disciplinary goals and the embattled condition of political science in many of our more vulnerable institutional sites, I believe that when it comes to building our departments, we cannot afford to take raising our rankings as our overriding goal. Citation and reputational metrics have an important place, but they should not dominate all our decisions concerning who we hire and promote, what sorts of research we do, and how and how much we teach. As a discipline, we can partner best with each other and contribute most if we embrace greater departmental pluralism. At many institutions, it makes sense to seek to create distinctive departments by recruiting scholars who work in different subfields with different methods, but whose substantive interests intersect sufficiently that the department can claim it collectively illuminates specific sets of significant political problems, more than other departments with different substantive emphases. Though a university’s administrators and supporters will never cease to take pride in highly ranked departments, they may well be still more favorable to ones that have well-earned reputations for scholarship and teaching that aid in understanding and addressing a visible subset of the world’s major political challenges.Footnote 5

We also need our departments to risk supporting civically engaged research in their hiring and promotion decisions, even prior to it becoming more central to the discipline, because that is how it can become more so. And most importantly of all, at all but a tiny handful of higher-education institutions, we need to accept that it has become crucial for political science departments to teach, not necessarily more, but better––in part through valuing colleagues who develop effective ways to assess and improve their own teaching and to aid the teaching of others, just as much as we value colleagues who produce impactful research. We will dissipate the main positive development for our discipline in these difficult times, the new emphasis on civic education in many locales, if professional leaders convey instead that we do not really regard our teaching as important or valuable.

For in the end, though it is commendable that many of us get intellectual pleasure from studying politics, we cannot forget that we earn the opportunity to do so only by benefiting those on whose support we rely. I personally find learning about politics endlessly fascinating, and I have also long believed that Aristotle was right to suggest that politics and political science are architectonic (Aristotle 1999, 1094a-1094b). Political institutions do much to construct the public and private spaces, including the realms of commerce, culture, and consciousness, in which people live their lives. So it is vitally important to learn why some political creations endure and others fall, why some help their inhabitants to grow and flourish and others leave people cramped and diminished. We must always remember, however, that for most people, projects of political understanding and construction are only steps toward creating conditions in which they can pursue many other worthwhile forms of happiness.

In this spirit, John Adams once wrote, “I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain” (Adams Reference Adams1780). I doubt that we will ever be able to cease studying politics, or, sadly, war; and I for one will always prefer politics to porcelain. But in doing our work, we must always remember that we seek to help create a world in which not just political science, but also mathematics and philosophy, navigation, commerce, architecture, and agriculture, and painting, poetry and music all can flourish. If we keep those broader and higher goals in view, and if we strive to pursue them in partnership with each other and with those we serve, then we and they might well find that there is much good that political science can do.