Many scholars are rightly doubtful that authoritarian regimes will curb government corruption—commonly defined as the misuse of public office for private gain (McGuire and Olson Reference McGuire and Olson1996; Carothers Reference Carothers2007; Chang and Golden Reference Chang and Golden2010; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2011; Pei Reference Pei2016). The reasoning behind these doubts goes something like this: Autocrats are unlikely to be motivated to carry out anti-corruption reforms because they often rely on distributing spoils and patronage to stay in power, benefit personally from corruption, and can use coercive means to suppress public criticism and unrest (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008). Any putative anti-corruption efforts are likely just a cover for autocrats purging rivals and consolidating power. Even if they did want cleaner government, autocrats would have to face the daunting prospect of giving up substantial power and control to get there. This is because corruption control is achieved, in the consensus view, through the power of democratic institutions: the rule of law, checks and balances, free and fair elections, independence for the judiciary and special investigatory committees, government transparency, a free media, public oversight through civil society organizations, and others (Brunetti and Weder Reference Brunetti and Weder2003; Alence Reference Alence2004; Johnston Reference Johnston2005, Reference Johnston2014; Lindstedt and Naurin Reference Lindstedt and Naurin2010; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2015). This democratic approach, however, is too risky for authoritarian regimes; what if increasingly independent courts or media turn and accuse the regime leadership of corruption? Even putting aside political considerations, authoritarian states may simply be too weak or disorganized to carry out substantial anti-corruption campaigns.

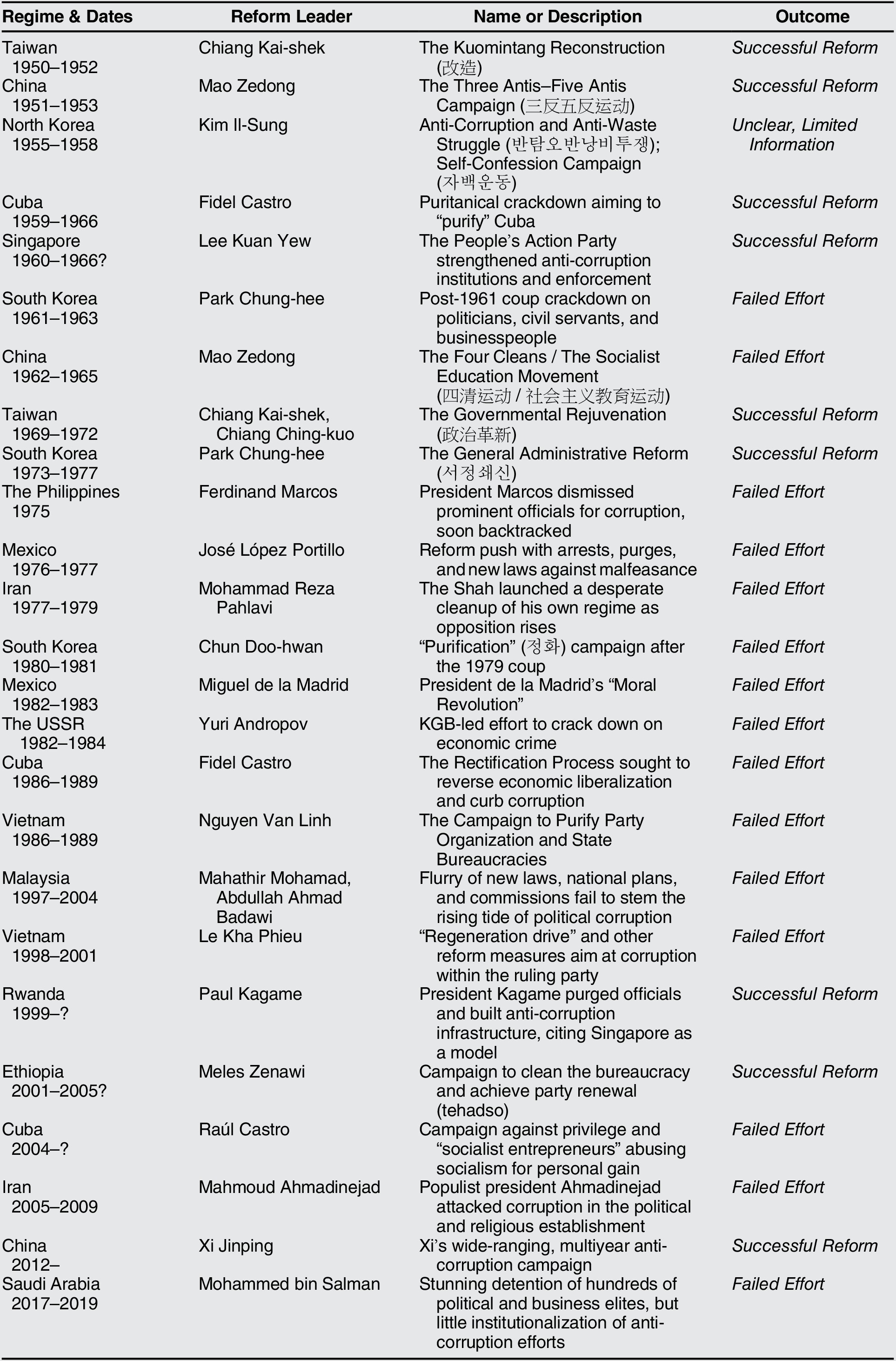

While there is some truth to this line of reasoning, I argue that authoritarian regimes curb corruption more frequently—and sometimes more effectively—than is widely acknowledged. There have been at least twenty-five substantial anti-corruption efforts by authoritarian regimes since 1950 (table 1). In particular, curbing corruption has for decades been a major agenda item for many authoritarian regimes that are “high-performing” in terms of governance and economic outcomes. I find that in at least nine cases corruption was significantly reduced nationwide, yielding political and economic benefits. These success cases are 1) more common than scholars have previously identified; 2) are not outliers, but present a pattern of behavior, as I explain later; and 3) occur in some large, important countries, such as China. Scholars often cite Singapore and maybe Rwanda as outlier cases in which authoritarian governments have managed to substantially curb corruption, but other success cases are rarely discussed except among country specialists (Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2015, 131, 149; Quah Reference Quah2017). In Taiwan, for example, the Kuomintang government pursued an ambitious set of reforms in the early 1950s that brought previously rampant corruption under control as part of laying a new foundation for regime stability and growth.

Table 1 National-level authoritarian anti-corruption efforts (1950– )

A question mark after a date denotes uncertainty on the date.

This argument is supported by evidence from a novel scoring system for anti-corruption efforts, which fills a gap in how scholarship systematically assesses such reforms. Previous studies have often not established comprehensive criteria for what constitutes an anti-corruption effort—beyond that reforms were announced—or how anti-corruption outcomes should be assessed (see Gillespie and Okruhlik Reference Gillespie and Okruhlik1988, Reference Gillespie and Okruhlik1991; Holmes Reference Holmes1993; Hollyer and Wantchekon Reference Hollyer and Wantchekon2015). In this paper, I define an anti-corruption effort as an announced reform push that achieves at least a 50% surge in corruption-related investigations and that reaches more than .01% of all public officials and bureaucrats in a country. To assess the success or failure of a case, I examine to what extent corrupt actors were disciplined and institutional reforms were made and enforced. In other words, I assess anti-corruption enforcement and rulemaking. These two aspects of reform are scored on an eight-point rubric and collectively determine an anti-corruption effort’s outcome. Enforcement is scored on its scope (or breadth) within the state, vertical reach, and permanence. Rulemaking is scored by judging the institutionalization of three types of reforms that impact corruption over a five-year period: reforms of organs tasked with anti-corruption work; reforms (or the elimination) of government institutions plagued by corruption; and reforms of laws, rules, or codes that directly address corrupt practices. Rulemaking is scored as more successful if reforms have vertical reach, addressing corruption both among elites and high-level officials and among low-level officials in rural or less wealthy areas. This scoring system was not created de novo, but draws on numerous studies that point to different aspects of anti-corruption reform that should factor into assessing its outcome (Gillespie and Okruhlik Reference Gillespie and Okruhlik1988, Reference Gillespie and Okruhlik1991; Holmes Reference Holmes1993; Pope Reference Pope2000; Manion Reference Manion2004; Hollyer and Wantchekon Reference Hollyer and Wantchekon2015; Pei Reference Pei2018). Appendix A (below) lays out the scoring system in more detail.

While many existing studies rely on Transparency International’s highly useful Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) (e.g., Yadav and Mukherjee Reference Yadav and Mukherjee2016), there are problems with using indexes of perceptions to assess authoritarian anti-corruption efforts. The distance between perceptions of corruption and actual corruption, which is always an issue when using indices like the CPI, is likely to be much greater in authoritarian regimes because they are less transparent. For example, the CPI rated Tunisia as one of the least corrupt countries in the Middle East and North Africa in 2010. But the next year, when President Ben Ali fell in the Arab Spring and his family’s massive corruption was revealed, Tunisia’s score dropped from 4.3 to 3.8, recoloring Tunisia into the bright red (indicating widespread corruption) that the CPI uses to shade most of the region on its annually updated map. This progression makes it seem as if Tunisia became more corrupt in 2011, when most likely what happened was that old corruption was revealed in the process of reform (Baumann Reference Baumann2017). Moreover, the CPI is impractical to use for this study because it is only comprehensive from the late 1990s onward, leaving out many consequential anti-corruption efforts of earlier decades. The CPI’s methodology has been criticized on several other grounds as well (Andersson and Heywood Reference Andersson and Heywood2009; Hough Reference Hough2017). In sum, a methodology focused on the actual actions a government takes promises a more accurate view than one based on perceptions.

One explanation for autocrats curbing corruption may be that, as some scholarship argues, autocrats in hybrid regimes use quasi-democratic institutions (QDI) to effectively mimic a democratic approach. Authoritarian regimes with quasi-democratic institutions such as semi-competitive elections or multiparty legislatures are often conceptualized as hybrid, competitive authoritarian, or semi-authoritarian regimes, among other terms (Carothers Reference Carothers2002; Diamond Reference Diamond2002; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002; Ottaway Reference Ottaway2003). In recent years, a booming literature has argued that QDI actually strengthen authoritarian regimes by making them more durable and improving their governance outcomes (Brancati Reference Brancati2014 reviews this literature). On corruption control, studies suggest that autocrats can use QDI to tie their hands, credibly committing to not predate on private businesses and to keep corruption low (Boix Reference Boix2003); that semi-competitive elections and legislatures can help regimes better monitor officials, bureaucrats, and business people (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011); and that opposition parties in multiparty legislatures can ally with private business interests to force autocrats to take corruption control seriously (Yadav and Mukherjee Reference Yadav and Mukherjee2016). Improvements in China’s pre-Xi Jinping anti-corruption efforts are sometimes attributed to the somewhat better rule of law, media freedoms, and government transparency that existed in the 2000s (Fu Reference Fu, McConville and Pils2013; Lorentzen Reference Lorentzen2014).

However, I find that cases of successful authoritarian reform have mostly not been the result of hybrid or quasi-democratic regimes employing the democratic approach, but rather of fully authoritarian regimes employing a decidedly authoritarian approach. Contrary to what one might expect, authoritarian regimes with quasi-democratic institutions have only rarely had success in curbing corruption (Carothers Reference Carothers2019). In South Korea, President Park Chung-hee’s anti-corruption efforts were much more successful under the dictatorial Fourth Republic (1972–1979) than in the competitive authoritarian Third Republic (1961–1972). Even while most fully authoritarian regimes are highly corrupt—dictatorships in Turkmenistan and Zimbabwe jump to mind—a subset of such regimes have curbed corruption more successfully than other nondemocracies.

Successful authoritarian anti-corruption reforms have in common that an ambitious leader uses his or her personal power to disrupt the state’s corrupt equilibrium and impose corruption control from above. This process can be seen through certain methods that are the basis of an authoritarian approach: the autocrat’s centralization of power, top-down control and penetration, and the use of regime propaganda. Centralization limits power to actors committed to reform, reducing veto players and allowing the leader to challenge entrenched interests; top-down control and penetration help the leadership to bypass protectionism in lower-level organizations and reduce bureaucratic resistance; and regime propaganda builds support and momentum for anti-corruption reforms while blocking out grassroots voices and participation. Interestingly, there are strong commonalities in the approach taken by successful autocrats even across authoritarian regime subtypes, such as military versus party regimes.

This anti-corruption approach is different from how democracies normally take on corruption. Corruption control in democracies relies on institutions that decentralize power across mutually checking organizations or bodies, as well as institutional features that constrain power within disinterested laws and rules, increase the public’s power to participate in government decision-making and the execution of policies, and make government more transparent (Klitgaard Reference Klitgaard1988; Pope Reference Pope2000). Some democratic leaders have at times borrowed from an authoritarian approach, as when leaders took personal control of controversial but ultimately effective anti-corruption efforts in post-Cold War Georgia and Romania (Kleinfeld Reference Kleinfeld2018). But even when a democratic leader is temporarily empowered to make bold reforms, this is by strong support from the electorate or legislators. An authoritarian approach does not allow for the horizontal and bottom-up checks on corrupt power that in democracies can lead to investigations of presidents and prime ministers, such as the investigation that resulted in South Korean president Park Geun-hye’s impeachment and removal from office in 2017. And civil society organizations and independent media are not allowed to report freely on wrongdoing and to lead public pressure campaigns against the government.

To summarize, authoritarian regimes combating corruption is more common than is widely thought, successful reforms are more than outliers and demonstrate a pattern of relying on distinctly authoritarian methods, and a new scoring system can help systematically assess anti-corruption efforts and outcomes.

I focus on Chinese president Xi Jinping’s wide-ranging anti-corruption campaign to illustrate these main points. China under Xi can be considered a crucial case or “least likely” case for successful authoritarian reform (Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975). The key to curbing corruption is thought to be strengthening democratic institutions, but since coming to power, Xi has substantially rolled back China’s limited political liberalization (Economy Reference Economy2018). This comes on top of the fact that China under the Chinese Communist Party is a fully authoritarian regime that does not have hybrid institutions or meaningful competition among political parties. Furthermore, it is commonly believed that personalist leaders are the most corrupt or the most accepting of corruption, and Xi is well-known to be personalizing power (Klitgaard Reference Klitgaard1988; Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003; Chang and Golden Reference Chang and Golden2010; Ezrow and Frantz Reference Ezrow and Frantz2011, 133). Unsurprisingly then, many observers have concluded that Xi’s campaign is about purging rivals or consolidating personal power and is highly unlikely to reduce systemic corruption (Huang Reference Huang2015; Lam Reference Lam2015a; Murong Xuecun Reference Xuecun2015; Youwei 2015; Pei Reference Pei2016).

The remainder of this essay is divided into two substantive sections and a conclusion. The first section analyzes authoritarian corruption control around the world. It uses a new scoring system to score twenty-five authoritarian anti-corruption efforts and analyzes the methods by which some autocrats have succeeded in curbing corruption. The second section lays out the evidence that Xi’s campaign has been effective at reducing corruption and is highly authoritarian. In the conclusion, I discuss the implications of these findings for the study of authoritarianism and suggest avenues for future research.

Authoritarian Corruption Control around the World

This section explains how my proposed scoring system applies to cases around the authoritarian world, highlights similarities in how corruption control was realized in the most successful cases, and shows the applicability of this analytical framework to cases beyond East Asia—where authoritarian anti-corruption success has been most common—by sketching the case of Rwanda.

Scoring Anti-Corruption Efforts

This study focuses on major, national-level reforms and campaigns that depart from routine low-level enforcement. These episodes represent the most challenging reforms for autocrats to undertake and have the clearest effect on a country’s overall level of corruption. It is not necessary for reforms to be exclusively or even primarily about corruption; in many cases, political leaders pursue corruption control within a larger reform agenda.

The first task, then, is to define and identify major anti-corruption efforts. To qualify, cases should meet three criteria. First, there should be an announced reform push with corruption control as a stated goal. Second, there should be a surge of at least 50% in corruption-related investigations from one year to the next. This can either be a surge in investigations into public officials and bureaucrats generally or, in an elite-focused campaign, a surge in just the number of elites and high-ranking officials investigated. The reasoning behind requiring a surge is that the reform effort should be distinct from routine anti-corruption enforcement, which varies dramatically across countries. Third, there should be at least .01% of all public officials and bureaucrats investigated. Or, in an elite-focused campaign, at least one hundred elites and high-ranking officials should be disciplined.Footnote 1 If the number of total public officials and bureaucrats is unavailable for a country in a certain timeframe, I use the standard of .001 percent of the national population. If a regime had been doing nothing against corruption, investigating a small number of low-level officials might not signal a major effort, despite being a quantifiable surge. For that reason, I set minimum thresholds on investigations.

With these standards, I identified twenty-five authoritarian anti-corruption efforts globally between 1950 and 2019. Numerous other campaigns and reform measures assessed did not qualify. For example, Russia’s president Dmitry Medvedev (2008–2012) repeatedly vowed to address the country’s well-known corruption problems, and his administration established an Anti-Corruption Council (Holmes Reference Holmes2012, 235). But anti-corruption prosecutions actually declined during his presidency (Krastev and Inozemtsev Reference Krastev and Inozemtsev2013). Medvedev himself admitted in 2011 that there were “very few successes in this direction” (Reuters 2011). This study draws on a wide array of sources to score cases, including government reports and data, analyses by international organizations and U.S. intelligence, interviews with country experts, and existing scholarship (table 1; figure 1). This list of twenty-five cases is incomplete but shows that significant reform efforts are not uncommon in authoritarian regimes.

The cutoff for a successful reform is four out of eight points because in order to score at least four points, an anti-corruption effort must have successfully implemented at least one institutional reform, taking it beyond just arresting offenders and into checking or disincentivizing future corrupt behavior. In a failed effort, an anti-corruption effort takes place, but investigations are either backtracked on, abandoned, or left unsupported by the institutionalization of new or strengthened anti-corruption rules. In a successful reform, by contrast, offenders are widely investigated and disciplined and new or strengthened rules are successfully enforced. In the most successful reforms, new or strengthened rules systematically constrain even corrupt behaviors by elites and high-level officials.

How Autocrats Curb Corruption

In the nine cases in which authoritarian regimes substantially curbed corruption, I find that autocrats largely used authoritarian methods at odds with the democratic approach, and that there were some commonalities in these methods across regimes. Rather than following conventional recommendations to strengthen the rule of law, checks and balances, or media freedoms, autocrats controlled and directed campaigns from above, taking extra-legal measures and quashing grassroots anti-corruption activism as necessary. Though specific anti-corruption laws and law enforcement tactics of course varied across cases, there were overarching commonalities: the use of power centralization, top-down control and penetration, and regime propaganda.

Moreover, anti-corruption campaigns in these cases did not coincide with political liberalization or the greater use of quasi-democratic institutions by regimes overall. This does not mean that a regime being fully authoritarian or being a personalized regime predicts effective corruption control—far from it. But among successful reforms in nondemocracies, anti-corruption efforts often coincide with a rollback of liberalization, as in Xi’s case, or a weakening or elimination of quasi-democratic institutions, as in the South Korean case. One partial exception is the case in Taiwan when premier Chiang Ching-kuo began a gradual political liberalization alongside anti-corruption efforts in the early 1970s by promoting “Taiwanization” and “youthification.”Footnote 2 Even so, Chiang smoothly succeeded his father and consolidated personal power over the Kuomintang regime.

Table 2 shows that many successful anti-corruption reforms led by authoritarian regimes share similar features. However, it also shows that Singapore was a deviant case. Corruption control under prime minister Lee Kuan Yew and his People’s Action Party involved a mixture of democratic and authoritarian approaches (see Vogel Reference Vogel, Sandhu, Wheatley and Alatas1989; Shang Reference Shang2002; Tan Reference Tan, Tay and Seda2003).

Figure 1 Select scoring of anti-corruption efforts

Table 2 Common features of successful authoritarian anti-corruption reform

Going beyond East Asia

Because the majority of success cases examined in this study are in East Asian countries, some observers might be tempted to see authoritarian anti-corruption as a product of Confucianism or East Asian cultural traditions more generally. It could be argued, for example, that Confucian precepts of benevolent autocracy continue to steer some East Asian leaders into taking hardline, moralistic stances against corruption. Scholars have noted that East Asian cultural traditions may shape the perception of corruption and therefore the politics of it in the region in different ways (Sun Reference Sun2001; Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Chaudhuri, Erkal and Gangadharan2005; Mensah Reference Mensah2014).

While how corruption is combated may be influenced by culture, authoritarian anti-corruption is not a culturally determined phenomenon. First, as a relatively fixed factor, culture does not help to explain the variation in corruption control outcomes within East Asian countries over time. China, South Korea, and Taiwan all experienced sharp variation in outcomes in the twentieth century, including sometimes even under the same autocrat. Second, several autocrats in the region who led anti-corruption reforms—including Mao Zedong, Chiang Kai-shek, and Park Chung-hee—portrayed themselves as modernizers daring to break with cultural traditions in order to improve their countries, whether in a communist, nationalist, or militarist direction. And third, there are similarities in the authoritarian approaches utilized in non-Asian success cases, such as in Cuba and Rwanda, as described later.

Instead, the concentration of cases in East Asia reflects the fact that successful authoritarian anti-corruption is more likely to occur in regimes that are relatively high-performing in terms of governance and economic outcomes. Scholars have long recognized the high variance in good governance and economic growth among authoritarian regimes—e.g., South Korea versus the Philippines or Rwanda versus Somalia (Bates Reference Bates1981; Haggard Reference Haggard1990; Wintrobe Reference Wintrobe1998). Several East Asian countries, including autocracies, rose into the high-performing category ahead of many other developing nations in the twentieth century. A great deal of scholarship has sought to explain this regional “miracle,” often citing factors such as the historical strength of East Asian states, certain legacies of Japanese and Western colonialism, and the rise of broad-based revolutionary movements (Johnson Reference Johnson1962; Kohli Reference Kohli1994; Wade Reference Wade1999; Woo-Cumings Reference Woo-Cumings1999; Hui Reference Hui2005). Since East Asian cultural traditions have shaped state development and other historical factors, culture may contribute to anti-corruption outcomes indirectly in this way (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1995, Reference Fukuyama2011). Nevertheless, high-performing authoritarian regimes have of course also emerged in other developing regions.

Anti-corruption reforms in Rwanda have been successful under autocratic president Paul Kagame. Kagame came to power after leading the Rwandan Patriotic Front to victory in 1994 and ending the Rwandan genocide. Given deference as a revolutionary hero, Kagame brooks no opposition and rules with relatively few constraints (Khisa Reference Khisa2016). Kagame has used his power to become an “illiberal state-builder” (Jones, DeOlveira, and Verhoeven Reference Jones, De Oliveira and Verhoeven2012). Citing Singapore as a model, he has sought to establish a strong political order, create rapid growth, and clean up rampant corruption. In October 1999, Kagame began a series of high-level anti-corruption purges, including of cabinet members and longtime political allies (Waugh Reference Waugh2004, 153). To institutionalize anti-corruption norms, Kagame oversaw the establishment of the “Office of the Ombudsman, the Anti-Corruption Unit in the Rwanda Revenue Authority, the Auditor General, and the National Tender Board” (World Bank 2015). International aid and development organizations, international press, and expert analysts have praised Kagame’s “rigid ethical standards” and anti-corruption measures (Kinzer Reference Kinzer2008, 236; Global Integrity 2009; The Mo Ibrahim Foundation 2016).

Xi Jinping’s Anti-Corruption Campaign

In this section, I introduce Xi’s campaign and use the eight-point scoring system to show how it has been successful at reducing government corruption in China. Of course, Xi’s campaign is in many ways politically self-serving, but I argue that this being the case does not preclude it from being effective. This section also examines how Xi has rejected the democratic approach and largely relied on an authoritarian approach to control corruption.

Xi Jinping, general secretary of the Communist Party from November 2012 and president of China from March 2013, wasted no time in launching a far-reaching anti-corruption campaign that would become the signature policy of his rule. In his first speech to the Politburo as general secretary, Xi denounced corruption and echoed claims by past leaders that its unchecked spread could “doom the party and the state.” His new administration swiftly put forward an Eight-point Code (八项规定) for party members to avoid extravagance and undisciplined behavior, especially in their dealings with the public. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), which led implementation of the campaign in Xi’s first term, saw its investigatory powers enhanced in several rounds of reforms. In late 2012, Deputy Party Secretary of Sichuan Province Li Chuncheng became the first senior official brought down by the CCDI as part of Xi’s campaign. Starting in 2013, the number of anti-corruption investigations into officials rose sharply, totaling nearly 2.7 million in the first five years (Xinhua 2017).

Beyond even the stunning total number of investigations, the most attention-catching aspect of Xi’s campaign has been the explosion of anti-corruption investigations against high-ranking officials—more than 212 in Xi’s first term.Footnote 3 Xi broke the informal norm of immunity from anti-corruption probes for Politburo Standing Committee members by opening an investigation against retired security chief Zhou Yongkang in August 2013. Zhou was only one of several “big tigers” brought down in the campaign, alongside former vice-chairmen of the Central Military Commission Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong, former chief of the General Office of the CCP Ling Jihua (a close adviser to Hu Jintao), and Vice-Chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Su Rong.

There is understandably much skepticism about Xi’s motives in this campaign. Some experts have cast doubt on whether this campaign is actually about curbing corruption, suggesting instead that its primary purpose is to consolidate Xi’s power, to weaken bureaucratic resistance to Xi’s policies, to “rejuvenate” the Chinese Communist Party, or simply to make a show of cleaning house for the public (Lam Reference Lam2015a; Murong Xuecun Reference Xuecun2015; Youwei 2015; Pei Reference Pei2018). Pei (Reference Pei2018, 228) writes that “not a single colleague who has worked closely with Xi before his ascent to power has been investigated or arrested during the five-year campaign.” Similarly cynical, Willy Wo-Lap Lam is a leading proponent of the theory that factional struggle best explains the anti-corruption campaign and indeed much of Chinese elite politics. Accordingly, some are skeptical that Xi’s campaign has curbed or ever can curb corruption. The campaign treats corruption as a moral failing and ignores the structural incentives behind the bulk of corrupt behavior, argues Huang (Reference Huang2015). “It is inconceivable that the CCP can reform the political and economic institutions of crony capitalism because these are the very foundations of the regime’s monopoly of power,” concludes Pei (Reference Pei2016, 267).

Why, then, should we not conclude that this campaign is a cover for Xi’s personal power consolidation? I argue that personal and governance goals are not mutually exclusive; Xi has used this anti-corruption campaign to strengthen his position and to curb corruption. The point is that personal power consolidation alone is an insufficient explanation for this campaign. While some particular investigations against elites may be purely political, the campaign’s investigations have by now burst the bounds of targeting any one faction, social group, sector of the economy, region, or type of official. Personal vendettas or factionalism can at most explain only part of this now eight-year campaign that has disciplined millions (Li Reference Li2016, 23; Wedeman Reference Wedeman2017). Furthermore, the complex reforms enforced by the campaign go far beyond power consolidation, including everything from limiting how many dishes public servants can order at restaurants to how city-level state-owned enterprises (SOEs) manage their accounts to streamlining reporting rules for lower-level committees involved in anti-corruption work. Xi’s campaign looks very different from typical autocratic uses of corruption as a smear against rivals just to consolidate power.

Scoring Xi’s Campaign

Despite numerous studies of this campaign, a systematic assessment of its corruption control outcomes at the national level is still lacking. The authoritarian nature of the CCP regime and the political sensitivity of this campaign make it exceedingly difficult to get a full picture. Nevertheless, my proposed scoring system can help organize the available evidence about this campaign’s accomplishments.

One sign of the campaign’s effectiveness is that discipline enforcement, though imperfect, has been undeniably far-reaching both horizontally and vertically within the party and state. Top officials from every province have been disciplined, along with more than seventy SOE executives and sixty-three generals between 2012 and 2017 (Li Reference Li2019, 55). In the first six years after the Eight-point Code was announced, the party has dealt with some 250,000 suspected violations of the anti-austerity and anti-extravagance rules, disciplining nearly 350,000 people (Xinhua 2018a). There has been no shortage of low-level officials disciplined—1.34 million cadres at the township level and below and more than .64 million rural cadres in Xi’s first term (Xinhua 2018b). As a result of investigations conducted all across the country, the CCDI confiscated 20.1 billion yuan in allegedly corrupt funds between the start of the campaign in late 2012 and June 2015 (Sina 2016a). Unlike in some previous Chinese campaigns, enforcement has not suffered significant backtracking. The conviction rate is over 99%, and virtually no high-ranking official publicly implicated has been exonerated or released after being imprisoned (RFI 2016). The unprecedented length of the campaign reflects strong political will at the top and makes it increasingly unlikely that its verdicts will be overturned. In sum, the campaign earns three points in the discipline enforcement category: scope of enforcement (1); vertical reach, meaning targeting elites (1); and permanence of punishments (1).

Anti-corruption bodies, procedures, and organizational arrangements that were established or enhanced in the campaign have become institutionalized. Under Xi, the CCDI’s ad hoc inspection teams have been “strengthened and enhanced in terms of their scope, intensity, and frequency of their inspections” (Guo Reference Guo2014, 613). More than half of the “leading cadres” brought down in the campaign, the CCDI reported in 2016, were initially discovered by inspection teams (Sina 2016b). The Xi administration also created central inspection groups—a new institution—to augment the existing inspection system. Because they report to the Leading Small Group on Central Inspection Work (中央巡视工作领导小组), which was headed by Xi’s deputy and CCDI chief Wang Qishan during Xi’s first term, these groups (teams) provide the “most direct channel for central supervision of leaders in both local government and key SOEs” (Yeo Reference Yeo2016, 60, emphasis original). The CCDI has also installed disciplinary inspection teams in central state and party institutions on a more permanent basis; it reported in January 2016 that it had successfully installed 47 such teams in all 139 central party and state institutions (CCDI 2016).

The latest and greatest in corruption control institution-building is the National Supervision Commission (国家监察委员会), an overarching anti-corruption body created in March 2018 by the National People’s Congress. The NSC can police not only the wrong doing of China’s roughly 90 million party members, as the CCDI does, but also non-party state employees. It has absorbed the anti-corruption functions of several governmental agencies, including the State Council Ministry of Supervision and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. Discipline inspection committees under the NSC can absorb 20% of procuratorates’ workforce nationwide—a massive personnel transfer (Li Reference Li2019). While the full impact of the NSC’s formation remains to be seen, this scale of institutionalization as a result of an anti-corruption campaign is unprecedented in the reform era (Keliher and Wu Reference Keliher and Wu2016).

It is clear that the campaign’s myriad anti-corruption laws and norms have substantially changed the behavior of Chinese officials and bureaucrats. As Elizabeth Economy writes, “Xi has sought to eliminate through regulation even the smallest opportunities for officials to abuse their position. Regulations now govern how many cars officials may own, the size of their homes, and whether they are permitted secretaries” (Economy Reference Economy2018, 30). Economic studies analyzing land transactions, luxury imports, car sales, and new business registration conclude that there has been success in curbing corruption in those areas (Qin and Wen Reference Qin and Wen2015; Chen and Zhong Reference Chen and (Zachary) Zhong2017; Chen and Kung Reference Chen and Kung2018). The same is true of studies that use the price discounts officials receive on housing and corporate spending on “entertainment and travel costs” as partial proxies for corruption (Chu, Kuang, and Zhao Reference Chu, Weida and Daxuan2019; Yi and Patten Reference Yi and Patten2019). Market research shows that party regulations against extravagant spending by officials in restaurants—“corruption on the tongue tips”—strongly affected the high-end dining industry starting in 2013, as well as the hotel industry (Jing Daily 2013). Government statistics show that the number of cases of misuse of public funds on dining, presents, and travel was initially large in 2013 but has been declining sharply year-on-year through 2017. If this trend is accurate, it suggests that enforcement of new rules has succeeded in deterring these behaviors (People’s Daily 2017). Overall, in terms of rulemaking, the campaign earns three points for institutionalizing reforms for at least a five-year period: reform of organs tasked with anti-corruption work (1), elimination or reform of governmental practices plagued with corruption (1), and revised laws and party rules that specifically address corrupt practices (1).

A major limitation of the campaign has been the failure to systematically enforce reforms that could address high-level corruption, such as among elites. The party’s “Rules for Disciplinary Action” (中国共产党纪律处分条例) put restrictions on the business activities of officials’ family members, which is seen as a crucial reform because so much high-level corruption is hidden in this manner. But, as Pei (Reference Pei2018, 220) explains, the party’s rules on this and many other proscribed activities remain so “vaguely defined” that they can be easily skirted, even after revisions to the “Rules for Disciplinary Action” in 2015.Footnote 4 Regulations have been similarly weak with regard to the country’s stock market, where corruption is common and China’s rich are getting richer. The CCDI signaled in November 2018 that it was working on new measures to address the problem. In an analysis of leaked documents, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) found “nearly 22,000 offshore clients with addresses in mainland China and Hong Kong … Among them are some of China’s most powerful men and women—including at least 15 of China’s richest, members of the National People’s Congress and executives from state-owned companies” (ICIJ 2014). Some leaked records point to problematic holdings by family members of current and past leaders, including Xi’s brother-in-law Deng Jiagui and former premier Wen Jiabao’s son Wen Yunsong (ICIJ 2014). Xi’s campaign proposes to prevent capital flight, tax evasion, and international money laundering, but international document leaks have revealed how troubled and contradictory these tasks are for China’s leaders.

A second limitation of the campaign is uneven implementation of anti-corruption reforms at lower levels of the state, such as at the township and village levels, especially in rural areas.Footnote 5 As China’s state media acknowledges, institutional change is “more difficult” in rural areas than elsewhere (Xinhua 2016). Corruption related to land use and expropriation continues to be common, and the party’s vast anti-poverty campaign still lends itself to misallocation of funds by rural cadres, despite some improvements to its administration (CECC 2017). The campaign’s challenges go beyond the vastness of the Chinese countryside and variation in local conditions. One key problem, as Juan Wang explains, is that the Xi administration inherited a situation of weakened state capacity at the lowest levels because of rising discontent and disaffection among village cadres since at least the early 2000s (Wang Reference Wang2017). Moreover, local governments under massive debt burdens and with weak capacity have in some cases been overwhelmed by the intrusive anti-corruption campaign and ground to a halt in “fear” and “paralysis” (Ahlers and Stepan Reference Ahlers, Stepan, Heilmann and Stepan2016).

Overall, Xi’s anti-corruption campaign involves substantial disciplinary action (3) and has enforced various institutional reforms (3), resulting in a score of six out of eight possible points. The campaign’s main limitations, which cost it two points, are failures of systematic enforcement of reforms at the extremes—at the high end among elites, and at the low end among rural officials. These problems are also cited by experts in their assessments of the campaign (Zhu Reference Zhu2015).

How do this score and the conclusion that the campaign has successfully carried out reforms stack up against existing expert opinion? Scholars who have taken on the question are split between those who conclude that the campaign has had a real if limited effect on corruption (e.g., Manion Reference Manion2016; Fang Reference Fang2017; Sun and Yuan Reference Sun and Yuan2017; Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2018; Economy Reference Economy2018) and those who do not see substantial improvements (e.g., Griffin, Liu, and Shu Reference Griffin, Liu and Shu2016; Pei Reference Pei2016, Reference Pei2018). This latter camp includes the World Bank’s control of corruption indicator and Transparency International’s CPI, both of which show only slight improvement in corruption control in China between 2011 and 2018. In the last estimate, therefore, my scoring of the campaign yields a somewhat more positive result than the majority of expert analyses.

Xi’s Authoritarian Methods

While some analysts have argued that China needs to take a more democratic approach or that the political liberalization of the pre-Xi era was promising for corruption control (Manion Reference Manion2004, 201; Pei Reference Pei2016; Ko and Weng Reference Ko and Weng2012; Fu Reference Fu, Trevaskes, Nesossi, Sapio and Biddulph2014), I find that it actually took an authoritarian approach to reduce corruption under Xi. This approach can be seen in at least three characteristics of Xi’s campaign: power centralization, including both personalization and institutional consolidation; top-down control and penetration, including bypassing certain government organs and even employing Maoist tactics; and regime propaganda, which has shut out independent media and public activism.

Power centralization in the campaign can be seen in both the personalization around Xi and the institutional consolidation under him. On personal power, official media highlights Xi’s leadership, Xi’s reforms, and Xi’s instructions for combating corruption. Outside analysts often refer to “Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign,” which was not common usage for previous campaigns under presidents Jiang Zemin or Hu Jintao. Xi has led the norm-breaking prosecution of several “big tigers” since 2013, though he reportedly consulted party elders before starting the first investigation against Zhou. Some analysts speculate—reasonably—that Xi’s status as one of the “princelings” (descendants of influential party officials) gave him more personal authority to challenge other elites (Hui Reference Hui2019). Xi is also seen as more charismatic than his predecessor Hu, with his minor cult of personality and regular use of folksy aphorisms (Lam Reference Lam2015b). These personal factors are likely important, but it is also true that they are to some degree a function of Xi already having accumulated power. After all, this cult of personality was not organic, but rather created at least in part through state-controlled media.

In terms of institutional centralization, the campaign bypasses governmental and legal organs that theoretically should be indispensable in anti-corruption work, like the judiciary, to consolidate power in the party center (Minzner Reference Minzner2015, 7). The law governing the NSC, the Supervision Law, does not put the NSC within China's legal system, but rather makes it “ultimately accountable only to the CCP” (Horsley Reference Horsley2018). In the military, Xi’s campaign has punished Central Military Commission-level leaders at an unprecedented scale and enacted a reorganization of military regions that entrenched interests had blocked under past administrations (Char Reference Char, Bitzinger and Char2018). While Chinese experts who are supportive of Xi’s anti-corruption efforts reject comparisons to Mao-era political campaigns, they accept that a party center-led “struggle” against corruption represents a return to CCP “tradition.”Footnote 6 As a professor at a prominent Party School explained in a frank interview: “Naturally, the center has to be powerful for our political system to work.”Footnote 7 This comment speaks to the logic that in such a large state ruling such a large country, there may be many veto players on any national reforms.

Alongside the centralization of the campaign, the Xi administration has increased top-down control. Greater top-down control allows the campaign to penetrate organizations in which corruption is being protected and to reduce bureaucratic resistance (Fabre Reference Fabre2017). One concern in the campaign has been to penetrate and reform corruption-sheltering “independent kingdoms” (独立王国) that had taken over parts of the state (People’s Daily 2018). The party has taken several measures to enhance the CCDI’s control over provincial and lower-level discipline inspection committees, such as advancing the “dual leadership system” (Guo and Li Reference Guo and Songfeng2015). Ad hoc inspections help avoid obstructionist bureaucracies and local governments. The obstruction-evading power of anti-corruption investigators is reflected in the use of the term “paratroopers”—meaning investigators who are “dropped” from the central government into lower-level party or government units to fight corruption (Caixin 2016).

At the individual level, while enforcement has been far less violent than in some previous campaigns and torture is theoretically banned, reports have come out detailing instances of torture, coerced confessions, and suicides by officials suspected of corruption (Human Rights Watch 2016). The campaign has taught the world the Chinese abbreviation shuanggui, which is a disciplinary procedure in which suspects are held indefinitely, incommunicado, and without the presumption of innocence. As one former CCDI member explained in an interview: “Sometimes there’s no other way. I used [shuanggui] sparingly because it was extralegal … history may judge us for it.”Footnote 8 While the new National Supervision Law appears to do away with the practice, it in effect means that shuanggui has been normalized and even strengthened.

Moreover, Xi has promoted the use of harsh Maoist tactics in the campaign. With its inspection teams, self-criticism sessions, and public political theater, Xi’s campaign “displays the unmistakable imprint of earlier Maoist anticorruption campaigns” (Duara and Perry Reference Duara and Perry2018, 24). Though this trend has alarmed many Chinese people, including some party members, it is part of Xi’s return to “seemingly anachronistic tools” of governance (Ahlers and Stepan Reference Ahlers, Stepan, Heilmann and Stepan2016, 37). While few believe that Xi can become a second Mao, his power consolidation, party-first agenda, ideological and anti-Western rhetoric, and wide-ranging crackdown on dissent are all reminiscent of Mao (Zhao Reference Zhao2016).

Finally, Xi’s administration has used propaganda and its control over the media to build the party’s narrative about the campaign and drum up public support. A flood of official media coverage of the campaign has sought to instill several messages: that anti-corruption efforts must be led by the party, that corruption is a personal moral failing rather than a result of perverse structural incentives, and that resisting the party’s campaign is futile. The extensively-promoted propaganda campaign “Remain true to our original aspiration and keep our mission firmly in mind” (不忘初心, 牢记使命) aims to revive in party members a spirit of public service and a sense of historical mission, which theoretically will deter them from corrupt activities. To drive home the idea that corruption is wrong and corrupt officials are bad people, sentencing documents often include salacious details about mistresses and extravagant spending.Footnote 9 In addition, the propaganda department has helped create several relatively high-quality television shows about the issue of corruption that have been commercially successful in recent years. The miniseries called Always on The Road (永远在路上) (2016), for example, trumpeted the party’s anti-corruption successes and aired emotional confessions by officials under arrest. Propaganda can also get personal—Xi has revived the party tradition of “democratic life meetings,” which are criticism and self-criticism sessions that psychologically pressure people to confess their crimes and to report others.

Any possibility of a more democratic approach to corruption control, such as through grassroots organizing against government corruption, has been blocked. Citizen activists with the New Citizens Movement, which has campaigned for governmental transparency over officials’ assets, have been detained and harassed (Human Rights Watch 2016). Chinese journalists report a “closing space” to cover corruption, explaining that the government is reporting less information on cases, defense lawyers are warier of talking to independent journalists, and independent journalists are more careful about what they write.Footnote 10 As one Chinese anti-corruption activist explained to me, the regime has “made anti-corruption more convenient” for itself by undermining its own legal procedures with suspects. In the Hu Jintao era, high-profile defendants would appeal their cases; now, they tearily confess their crimes for documentaries used in regime propaganda. One journalist I interviewed claimed to have solid leads on corruption by more than one Central Committee member, but that she was not allowed by her superiors to investigate further.

Conclusion

This study’s findings about corruption control and the methods used to achieve it have broader theoretical implications for the study of authoritarianism. The findings suggest that authoritarian regimes succeed in overcoming challenges—corruption being an especially hard challenge—by using their particular institutional strengths as autocracies, rather than by becoming more like democracies. This conclusion is at odds with three related views on authoritarian regimes that are common or influential in the field today: 1) the theory that authoritarian regimes that have quasi-democratic institutions are more durable and more effective at governing in various ways (Brancati Reference Brancati2014); 2) the widespread—and generally accurate—view that authoritarian personalism is associated with chaotic governance, economic mismanagement, and rampant corruption (Nathan Reference Nathan2003; Chang and Golden Reference Chang and Golden2010); and 3) the theory that the provision of public goods in authoritarian regimes is dependent on the autocrat needing to satisfy a broad “winning coalition” (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003). Without seeking to overturn these views in the field, this study nevertheless shows that successful authoritarian reforms are often by regimes with narrow power structures relying on a decidedly autocratic approach.

While authoritarian personalism is rightly associated with terrible governance outcomes, this study finds that authoritarian anti-corruption is often imposed by individually powerful leaders, and that one feature of an authoritarian approach to corruption control is power centralization. This suggests that in some cases personalism is an authoritarian asset. The personalization of power can reduce the number of veto players who can block reform and allow anti-corruption institutions to simulate independence while still being under the control of the autocrat. It can help an autocrat pierce local protectionism on a national scale, which is necessary to address many corrupt government practices that directly affect citizens. In regime propaganda, the individual leader can be used as a symbol of incorruptibility or personification of the government’s efforts to clean house. I am not attempting to reprise a hoary argument for the “enlightened autocrat;” most personalists are not steady-handed reformers, and even those who are, are often ruthless toward their citizens and quash grassroots attempts to improve society. Nevertheless, there are nuances even to what is often thought of as one of the worst parts of authoritarianism.

The selectorate theory of politics claims that authoritarian regimes are likely to provide public goods—corruption control being an important public good—only if the autocrat has a broad “winning coalition.” This makes intuitive sense because autocrats in this situation face political incentives much closer to those of democratic leaders who have to satisfy a mass electorate. However, my study finds that effective authoritarian anti-corruption has often been led by autocrats with narrow winning coalitions, who are unaccountable even compared to many other autocrats. All accounts suggest that Xi Jinping’s winning coalition is narrower than those of his immediate predecessors Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, though the exact size of any winning coalition is unknowable. My finding here follows other recent studies that have demonstrated surprising authoritarian public goods provision, such as Lily Tsai (Reference Tsai2007) on public goods in rural China and Michael Albertus (Reference Albertus2015) on authoritarian land reform.

Why might autocrats who do not answer to a broad coalition of supporters try to curb government corruption? While a full explanation of autocrats’ motives for corruption control is beyond the scope of this study, in several cases already discussed, autocrats saw some degree of good governance as necessary to secure their regimes against serious threats, such as those South Korea faced from North Korea or Taiwan faced from China. Another possibility is that autocrats see excessive corruption as hampering their larger political or economic projects, such as achieving rapid industrialization or building communism. In all these cases, having a broad winning coalition may actually be a drawback; it may result in an autocrat needing to make too many compromises with entrenched interests to carry out bold reforms. In Vietnam, for example, autocrat-led anti-corruption efforts have been repeatedly blocked by powerful conservative elites (refer to table 1). The Vietnamese Communist Party’s tradition of collective leadership prevents any one leader from being able to simply impose major reforms (Thayer Reference Thayer2017).

Besides theory, my main contribution is a scoring system for empirically evaluating anti-corruption efforts. This scoring system could be adopted and improved upon by other scholars studying corruption control in other times, places, and contexts, including subnational reforms. It could also inform policy in cases where policymakers need a way to assess how seriously to take an authoritarian government’s claims to be carrying out anti-corruption reforms. For instance, how serious is Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s anti-corruption campaign in Saudi Arabia? My proposed scoring system is a framework in which to structure an answer to that question, and in which to compare the campaign to Xi Jinping’s in China and other contemporary cases.

I have focused on establishing the extent and character of authoritarian anti-corruption reform, which leaves open some obvious next questions: Why do some authoritarian regimes succeed in curbing corruption but not others? When for autocrats do the political benefits of curbing corruption outweigh those of engaging in and accepting it? If the authoritarian methods I identify are so useful, then why do only some autocrats use them? Taking up these questions could improve our understanding of the role of corruption and anti-corruption in authoritarian politics.

Appendix A. Scoring Anti-Corruption Efforts: Enforcement and Rulemaking

Enforcement: Beyond the minimum level necessary for a campaign to qualify as an anti-corruption effort, enforcement can be judged on its scope (or breadth), vertical reach, and permanence.

-

I. If investigations against corruption or related economic crimes were carried out widely within the state and regime, including in a majority of bureaus or ministries or a majority of provinces/states/geographic regions, add 1 point.

If investigations against corruption or related economic crimes were carried out narrowly, targeting or seeming to target only a political faction, province, or state at odds with the regime, or a particular ethnic or religious group, add 0 points.

-

II. If at least 1% of elites or high-level officials were severely disciplined for corruption, meaning at least dismissed from all positions of power, add 1 point.

If elites were avoided in the campaign or elites largely avoided punishment despite credible accusations, add 0 points.

-

III. If the vast majority of punishments were enforced with little or no backtracking, add 1 point.

If investigations were blocked, convictions were later reversed, or there was significant backtracking on actual punishments, add 0 points.

Rulemaking: There are broadly three types of reform having to do with institutions, laws, and norms that can directly impact corruption.

-

I. Creation or reform of organs tasked with anti-corruption work to strengthen the powers to discover, investigate, or prosecute wrongdoing

-

II. Institutional measures that eliminate or reform a governmental body or governmental practices plagued with corruption

-

III. New or revised laws, regulations, or party rules that specifically address corrupt practices (sometimes overlapping with Type II)

Reforms in any of these three categories may or may not achieve institutionalization—meaning that the reforms “sink in” or “stick” for at least five years after being announced. Multiple reforms in the same category in the same campaign—for example, two anti-corruption laws passed in the same year and then successfully implemented—do not add more points. However, Type II and Type III reforms are judged as more successful if they have vertical reach. Reforms that systematically address corruption among elites and high-level officials as well as low-level officials in rural or less wealthy areas can earn an extra point in each category, as follows:

-

Type I reform was successful if changes to anti-corruption work endured and were integrated into the state’s existing anti-corruption infrastructure. (add 1 point)

-

Type II reform was successful if the measures were not reversed, improper practices continued to be sanctioned, and violators continued to be disciplined. (add 1 point)

If a Type II reform systematically addressed improper governmental or bureaucratic practices by both high-level and low-level officials, add 1 point.

-

Type III reform was successful if the new or modified rules continued to be enforced, as seen in their usage in anti-corruption investigations or prosecutions. (add 1 point)

If a Type III reform systematically addressed corruption by elites and high-level officials as well as low-level offenders, add 1 point.

Successful Reform: An anti-corruption effort achieves a cumulative score of at least 4 points (50%), indicating that it has gone beyond just enforcement and has put in place at least one substantial institutional reform to prevent or disincentivize future corruption.