The weak as well as the strong, the threatened as much as the ascendant, have ever turned to the petition to advance their cause or defend that of others. At the same time that Henry Clay launched a petitioning campaign in 1832 to defend the Bank of the United States from the attacks of President Andrew Jackson, African-Americans and their allies were using petitions to advance the antislavery movement.Footnote 1 In the midst of these more public controversies, Native Americans ranging from Cherokee women to the Seneca orator Red Jacket were using petitions, sometimes with stunning success, to defend their lands from dispossession.Footnote 2 Four decades before and across the Atlantic, revolutionaries in France had seized upon a petition-like document—the cahier de doléances—to articulate their rhetoric and organize their ranks. Amidst the upheaval, French Jews embraced the cahier among other tools to build the momentum for their eventual liberation. As if prophetically, the Abbé de Sieyès had just one year before scoured the records and cahiers of the previous estates-general (1614), where he found the basis for his celebrated pamphlet “What Is the Third Estate?” (1789).Footnote 3 So, too, in the ongoing battle for basic freedoms in authoritarian regimes—whether Charter 08 in China or a Cuban petition of 11,000 signatories in 2002—dissidents put their democratic hopes in an ancient tool of monarchy and empire: the petition.Footnote 4

The petition stands as one of the most common and momentous institutions in the history of monarchical and republican government. Some of the most consequential documents in the political development of Europe and North America have taken the petition form—the petitions of barons and “Articles of the Barons” to King John that engendered the Magna Carta, the celebrated “petitions of right” to European crowns (including the 1628 Petition of Right), mass petitions during the English, French, and 1848 Revolutions, the Chartist movement in England (where single petitions had over a million signatures)Footnote 5, and the Olive Branch Petition and other documents in the Americans’ War for Independence,Footnote 6 among others. Petitions figured critically in the emergence of Protestantism and a public sphere in early modern Europe.Footnote 7 In the United States, where petitioning is an established right written into the text of the Constitution,Footnote 8 circulated petitions were staple features of the most influential political movements of American history—anti-Sabbatarianism, temperance and prohibitionism, abolitionism, several suffrage and civil rights movements (for the propertyless, for African-Americans, for Native Americans, and for women), the populist and anti-monopoly campaigns, and numerous others. Even in the present age of mass communications, printed and electronic petitions remain a common feature of mass and special-interest political participation.Footnote 9

Despite (or perhaps because of) its ubiquity, the petition exhibits some curious properties. Evidence from a number of studies suggests that many petitions are ignored by their intended recipients—kings, bishops, governors, legislatures, courts. In the heyday of English petitioning in the seventeenth century, “a substantial crop of petitions [was] presented by political activists under no sort of illusion either that the grievance was unknown or that Parliament might reasonably be expected to respond by redressing it.”Footnote 10 As even the eminent jurist Sir Edward Coke could admit, many petitions of grace to the English crown were sent without expectation of an answer.Footnote 11 Further evidence of rulers ignoring petitions appears in narratives of petitions to Roman emperors and imperial administrators,Footnote 12 antislavery petitions in the antebellum U.S. republic,Footnote 13 and recent mass petitions in Latin America.Footnote 14 Further, there are formidable hurdles to the credibility of any petition—the forging or overcounting of signatures, the very real possibility that signatories may not fully embrace the entire intent of the petition when signing it, and the tenuous link between petitioning, voting, and political authority.Footnote 15 In short, we face several sticky puzzles when thinking about the petition in modern political society:

Why does the petition flourish when the document is so often ignored, and known to be ignored, by its intended recipient?

Why does the petition flourish when it is so difficult to establish credibility?

After having gathered hundreds or thousands of signatures, why do petitioners seek even more signatories when the demonstrative force of yet another name is marginal?

No answer to these questions can be attempted outside of the context—political, historical, gendered, racial, economic, and other—in which petitions are undertaken. Yet when we conceive of petitions less as purely expressive documents and more as sponsored devices wedded to political mobilization, we arrive at one (by no means the only) answer to these questions.Footnote 16 My central claim is that many petitions serve as technologies through which political actors identify sympathetic citizens and recruit them to their causes. Recruitment by petition is often complimentary to the messaging function of petitions—petitions both signal and recruit, and one function often depends upon the other—yet the recruitment potential of petitions remains largely ignored and thus forms the center of my analysis. My argument proceeds from two empirical features of petitions and the petitioning process.

The first is sponsorship. While historians, literary scholars, sociologists, and political scientists have long viewed petition signing as an act of individual expression,Footnote 17 the fact remains that many (perhaps most) petitions are created, subsidized, and circulated by political organizations or networks—reform societies, social-movement organizations, splinter groups, guilds and unions, interest groups, and occasionally even political parties. Indeed, many individual petitioners affix their signatures to a petition only after having been requested to sign it. It is not so much the signatory who seeks the petition, but the petition that seeks the signatory.

The second empirical feature is the petition’s structure. The directed petition is a document with two features: (1) a prayer or declaration of principle, policy or grievance (usually addressed to a ruler or representative body), and (2) a signatory list comprising the written names of those who support the prayer. In the common understanding and academic study of petitions alike, it is the prayer that harvests virtually all consideration.Footnote 18 The signatory list deserves sustained scholarly attention, however, as it comprises a rich political resource with at least three dimensions: (1) it generates a matrix of information—a “database” of sorts—on possible supporters; (2) the process of constructing that database creates new networks and affiliations; and (3) the signatory list offers safety in numbers and notables to potential recruits uncertain of the sponsor’s value.

Petitions undoubtedly serve numerous purposes—individual expression, signifying commitment to a cause, signaling a ruler, establishing legitimacy, submitting matters for consideration to a legislature or ruler, elaborating grievances or principles of belief, and many others. I focus rather narrowly and analytically here upon their organizational and mobilizing value. Approaching petitions this way abstracts somewhat from the rich political and historical contexts in which they circulate, but also highlights features of petitions that elude analysis. Such an approach also links petitions with the study of political subversion and “contentious politics,” in part because petitions often compose part of the repertoire of collective action.Footnote 19

I elaborate this account first theoretically and employ three historical case studies to illustrate the logic and mechanisms of the theory and to test some of its predictions. The cases are chosen to illuminate specific applications of the theory. The explosion of American antislavery petitioning in the 1830s fueled the resurgence of a highly consequential movement and transformed women’s political identity and activism.Footnote 20 Yet it came at a time when radical abolitionism had difficulty attracting followers, and during a congressional gag rule under which antislavery activists knew they were sending petitions to a Congress that would with certainty ignore and actively table them. A recruitment-based perspective provides a unique window into why antislavery petitions were nonetheless sent by the thousands.

Two cases from early-modern Europe demonstrate both the power of the petition in fluid situations of uncertainty and the critical importance of the signatory list. The emergence of Protestantism in sixteenth-century Europe both stemmed from and contributed to a context of repression and violence. For Protestants looking to build churches, communities, and some measure of political power, it was difficult to locate allies in a population that included rigidly opposed Catholics, potentially Catholic allies, and potential Protestants. A pathbreaking study by historian Allan Tulchin centered in Nîmes, France, demonstrates the organizing power of petition-like claims upon the Crown (the cahier général or cahier de doléance).Footnote 21 Drawing upon other archival documents and the Tulchin study, I discuss how various petitioning forms (the cahier, the requête, the supplique) became critical organizing tools for Protestants. The Protestant case also demonstrates the recruitment power of petitions in a non-Anglo-American, pre-democratic context (ancien régime France) and shows that the petition as a political institution can serve as an organizing tool for religious persuasion.Footnote 22 Finally, the efforts of the newly-recomposed English Crown in the 1660s to regulate petition signatory lists in the Tumultuous Petitioning Act of 1661 composes the last, and shortest, case considered here. It shows the focused effort of a newly-established and anxious authority that constrained petitioning’s recruitment power by limiting the size of signatory lists.

Because I advance a plausibility exercise—sketching the outlines and essential logic of a yet-to-be fully elaborated or formalized theory—these cases do not compose a quasi-experimental sample.Footnote 23 Because neither a theoretical account of recruitment by petition nor a general theoretical account of petitioning exists,Footnote 24 I select these cases because their comparison illustrates possible dynamics and mechanisms in play,Footnote 25 thereby serving purposes of “ontology” as much as methodology.Footnote 26 I leave for future research the task of testing the theory with true quasi-experimental analysis of similarly situated comparative-historical cases.

After discussing the cases, I conclude with reflections on the extent to which the logic of the present theory remains applicable to contemporary petitions, including digital petitions.

The Petition as Recruitment Technology under Two-Sided Uncertainty

Scholars usually lump together petitions with categories that feel more natural to them. Petitions become part of “contentious politics” and social movements, or they fall under more normal “political participation.”Footnote 27 While petitions compose a part of all these phenomena, they deserve their own, separate, and sustained attention. For one, citizens and non-citizens often petition outside of social movements as much as within them. When activists or movements take up petitions, they use a tool that both predates their cause and will outlast their activity. Unlike many elections in which citizens vote for a candidate, and do so secretly, petitions explicitly advance or reject a particular claim and their signatories identify themselves publicly. While petitioning takes on many forms in variable contexts, these features of petitions mark their use across a range of imperial, monarchical, ecclesiastical, authoritarian, republican, and democratic contexts over many centuries.Footnote 28

In contentious politics, political entrepreneurs face the complicated and costly task of recruiting people who agree with their cause on specific issues.Footnote 29 In some environments, such as where there exist well-established parties or interest groups, partisanship or public affiliation with an organization can be used to advance recruitment. Yet for many emerging issues—on which major parties have not yet divided or for which people do not readily identify their positions due to uncertainty, complexity, novelty, or controversy—neither strategies of party-based search nor harnessing existing organizations will provide much recruitment value. The issue of slavery under the second American party system (Democrats versus Whigs) offers an example. The two major parties divided mostly on issues of trade, tariffs, and national infrastructure. Anti-slavery Democrats co-existed with pro-slavery Whigs, and it took a decade from the first organization of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) to create the first anti-slavery party (the Liberty Party).Footnote 30 Civil rights have often served as similar “second dimension” issues in American political history, on which intra-party divisions are notable.Footnote 31

Controversy and risk often accompany new movements. Environments of potential mobilization confront organization builders with informational challenges that amount to a particular form of two-sided uncertainty.Footnote 32 Citizens may conceal their true preferences about an issue or a new movement due to the “reputational utility” of falsification.Footnote 33 Just as likely, citizens may not know their own preferences on a given issue because they lack information about the alternatives being proposed and their consequences. Builders of new organizations—call them political entrepreneursFootnote 34—do not know where their likely friends and potential joiners are. They do not know who is with them, who is against, who is undecided, and how much so. Beyond parties, other established organizations such as religious congregations and associations or groups may not yet have taken a position on the issue, or their members may be significantly divided. Potential converts may not know exactly what they are attaching themselves to; possible joiners have uncertainty about what the movement stands for, and whether it will be effective.

The petition provides a powerful recruitment tool in such environments. Recruiting petitions have the property of a technology because they adapt a common mechanism—a prayer bundled with a signatory list—across many particular forms. The petition can offer a simple prayer, with blunt statements of principle or grievance, or can advance complex prayers (with elaborate philosophical and legal arguments or structured lists of demands). The signatory list may consist of a group that signs under a common associational title (“the weavers of Hull,” “the women of Worcester”), signs by surname and initial only, or by “marks” of assent.Footnote 35 Many contemporary petitions contain multidimensional arrays of information on signatories (including geographic or electronic addresses). Recruitment by petition requires information in the prayer linked to information in the signatory list.

The Petition as Advertisement and Database for the Organizer

The process of petition circulation can be seen as an institutional protocol—figuratively, a series of if-then statements—whereby an agent (canvasser) searches through a population sequentially, by asking some smaller set of individuals whether or not they agree, perhaps asking each signatory for the names of those who would sign, then updating and moving to the next possible signatory. Agreement with the prayer is a noisy but useful indicator of the probability with which the signatory will expend further energies on behalf of the organization (joining as a member, contributing money or other resources, canvassing, rallying, signing more petitions, or perhaps voting).

The petition having been completed, the sponsoring organization now has three resources. First, the petition lists individuals, implicitly differentiating those who agree from those who do not. Even in the absence of other information about the signatories, the size of this set is useful as an indicator of the breadth of support for the organization’s cause. As such, the signatory list comprises a database of sorts, summarizing information about potential supporters.

Second, by one of two mechanisms the sponsoring organization has information on the social location of sympathizers. The first mechanism depends upon the information carried in the signatory list. Consider first the case (common in petitions) that the signatory list contains names only, without other information. In small-world contexts where an individual is known by others in the community—and their domicile, personality, family, trade, and other traits are readily identified upon hearing their name—the signature alone can reveal useful information about social location. This is particularly true for community elites or “local notables” whose names are likely to be more readily identifiable on a petition, and whose signatures may rest at the top of the signatory list as a signal to others who are asked to sign it. (A more direct case is where an electronic or postal address, telephone number or other means of communication accompanies the signature.)Footnote 36 The second mechanism depends upon the canvasser and her local knowledge of the population. The canvasser, who has approached individuals, now knows who has signed and where they are located (their domicile, their membership in a church). Armed with this knowledge, she can find and recruit these individuals. This local knowledge renders the canvasser a crucial agent in the political organization.Footnote 37

Third, the canvasser has created a new network of affiliation by virtue of having met and conversed with sympathizers and signatories. Of course the creation and structure of this network are not at all exogenous; the canvasser will have relied to some extent upon pre-existing social networks in gathering signatures.

Safety in Numbers and Notables: The Petition and the Potential Signatory

Every potential signatory to a petition is also a potential member and contributor to one or more affiliated organizations. How might different features of the petition assist in recruiting these members? Activists find the first tool in the political information of the petition’s prayer, which offers one or more expressions of policy or belief to which the organization is publicly committed. The petition’s prayer may elaborate these in some detail. Upon reading the prayer, the potential signatory can say: “here is a principle or policy for which this Organization/Movement stands.” In this sense, the historical petition is a forerunner of modern political advertising, which also broadcasts policy positions taken by candidates, groups, movements, and parties.

While the prayer offers information, there is risk in publicizing what the group does. Even a fledgling organization may have internal divisions, and the entrepreneurs who build such organizations may be controversial. For this reason, recruiting organizations will often begin their petitioning campaigns with prayers that reflect moderation (avoiding the extreme or most controversial views of their group) and also employ ambiguity, such that the language might appeal to more than one audience.

The messaging function of the petition’s prayer aligns its utility well with other tools of the modern social movement,Footnote 38 including advertising (both explicit in the form of paid commercial messages in print, audio, and digital media, and implicit in the form of other publicity activities), pamphleteering and rhetorical argumentation, voting, marches, boycotts, and other protest activity, and occasionally more risky and radical measures such as civil disobedience and violence. Petitions often travel with these strategies as part of a larger tool kit of contentious politics.Footnote 39

Petitioning differs from these other tools on critical ways, not least being that non-voters and even non-citizens can sign them. Hence those marginalized by the incumbent regime (with less or no power) can participate and organize by petition. Unlike the tools of political advertising and in-person protest, moreover, the petition comes with a signatory list. The accumulation of names on a signatory list can assist in the establishment of legitimacy for the petition sponsor. An organization’s potential sympathizers may be ambiguous or uncertain about the organization’s cause and the value of joining. By demonstrating that others, perhaps many others, support the petition’s prayer, the petition can reduce the vulnerability felt by yet uncommitted sympathizers. The presence of “notable” signatories (either local notables or recognizable celebrities) can also give the potential joiner comfort. Sheer numbers and notable names may give both information and a sense of relative safety to the potential signatory, and may make joining easier.

Safety in numbers matters because for the directed petition, the individual’s signature is something of a public commitment to a policy position. This has advantages and disadvantages. Among the disadvantages are that the sympathizers of a movement or cause can be identified and signaled out by opponents for intimidation or violence.Footnote 40 Among the benefits of this publicity is that the individual can declare her allegiance to a policy whose details remain uncertain, without having to marshal rhetorical talent or individual argumentation in doing so. Unlike the individual letter,Footnote 41 the petition presents a larger community of sympathizers, and unlike most letters, the petition is circulated or made publicly available. The number of signatures previously affixed gives some indication of the size of the community, the commonality of the prayer’s stance, and the fact that others have taken the risk of signing and expressing their assent. Hence signing a petition usually entails both greater publicity and greater “power in numbers” than does a letter-writing campaign.

Safety in notables is different but just as powerful. The size of the supportive population may matter less to some potential signatories than the presence of particular people whose views are trusted and legitimated. The structure of the directed petition, with its prayer followed by a sequentially-expanding signatory list, facilitates recruitment because early signatures provide a signal of sorts to later signatories. Since names are placed upon a petition sequentially, many potential signatories may observe part or all of the previous signatory list before deciding whether to affix their name to the document.Footnote 42 If the next potential signatory is uncertain about the value of signing, earlier signatures may reduce this uncertainty, showing that similarly situated individuals found it worth their while to sign. In this way, early signatories can lend local legitimacy to a petition (though they can, of course, induce some individuals not to sign if they see the signature of someone with whom they disagree or who is particularly controversial). One implication of this structural feature is that we might expect the earliest signatories to a document to be local notables whose identification with the declaration serves to popularize that statement and to reduce the risk perceived by potential signatories. To the extent that petitions serve as “weapons of the weak,” they often court the energy and alliance of the strong.Footnote 43

When combined with the cascade of legitimacy that can result from a growing signatory list, the fact of two-sided uncertainty explains why petition signers often gain more confidence after affixing their names.Footnote 44 Analysts of digital petitions often see signing them as a form of “lurking” participation for those not previously active.Footnote 45

How these patterns accumulate into movement formation is variable and not always clear. Yet because petitions can serve to match those who seek followers and joiners with those who seek meaning and movements, the recruitment function of petitioning is often situated at the transition between what contentious politics theorists Douglas McAdam, Sidney Tarrow, and Charles Tilly call the “contained” and “transgressive” phases of movements.Footnote 46 Petitions derive from ecclesiastical, imperial, and monarchical institutions that extend hundreds and even thousands of years into the past.Footnote 47 In this sense they compose a part of normal politics. Yet various theorists of contentious politics have located new forms of resistance in the subversion of normal, seemingly everyday political institutions and practices.Footnote 48 Emergent organizations and movements often convert the repertoires of “regular,” traditional and contained politics into new repertoires of more radical action.Footnote 49

Whether in its ecclesiastical, imperial or monarchical past or its more democratized present, the petition embodies a tension between the tangible and the theoretical. As James Scott argued of peasants in Weapons of the Weak,Footnote 50 petition signers are often as or more animated by concrete, accessible grievances than by ideological commitments. Yet because the prayer embeds these grievances in rhetoric that advances more general principles, and because the process of canvassing involves activists and potential joiners in argumentation, the petition weds local issues to more general ideologies and philosophies. The petition exists, indeed thrives, in a liminal political space located between the articulation of local grievances and the discourse of abstract ideas.

Predictions and Implications: Recruitment versus “Signaling the Sovereign”

Having summarized the core features of a recruitment-based account of petitioning, it is useful to elaborate empirical expectations associated with the theory. In juxtaposition to the recruitment perspective, an alternative, “stock” theory of the petition would cohere roughly with a signaling theory of political communication. Under this interpretation, the petition is a costly and informative signal of the breadth of public sentiment on a given issue.Footnote 51 The petition might accomplish this task in two ways, first by displaying the large number of sympathizers with the cause, and second by implicitly displaying the immense energy that activists have spent canvassing for names. It is, then, not simply the signing of a petition but the aggressive circulation of petitions by activists that functions as a signal of constituent “type” to the uncertain sovereign.

The core distinction of the recruitment-based theory is that it takes the primary audience of the petition as not the sovereign recipient, but the public. Both mobilization and signaling theories of the petition predict that organizers would wish to maximize the number of signatories, but for different reasons.

The sovereign-based theory of petitions predicts that they will be structured in such as a way as to express costly (informative) activity on the part of activists and signatories. An important feature of the sovereign-based petition, therefore, is its credibility to the sovereign; to what extent does the petition induce the ruler to change her beliefs about the “type” of her constituents? (If the legislator in the 1830s United States already believed that most of his constituency was antislavery, then there would be little point in petitioning that person, at least from the signaling perspective.) Credibility also concerns the extent to which the petition allows the sovereign to differentiate between casual movement sentiment and genuine commitment or more developed ideology.

In contrast to—and in addition to—a theory of petitioning in which the primary or only audience is the sovereign, the recruitment-based petitioning perspective makes a number of testable predictions that can be assessed using narrative and quantitative evidence.

Petitioning practices that aim for recruitment over (or in addition to) persuading the sovereign will exhibit distinct patterns. At the most elementary, a recruitment-based petition may often be sent to officials who are not in the best (authoritative) position to act upon the wishes or grievances expressed in its prayer (what I call the not-sent-to-sovereign prediction). So too, if petitioning organizations and activists care little about persuading the sovereign, they may retain the original copy of the petition, withholding the most authentic copy from the sovereign, and keep the original signed version, either as a “database” of potential supporters or as evidence to local audiences of the various people who have signed on to the cause (original copy kept prediction).

Beyond this, the recruitment potential of petitioning has the greatest “value-added” precisely when other methods of recruitment are weakest, that is, when party labels and other distinctions convey little information about the issue at hand. It is quite possible that in many settings, emergent social-movement activity presents just such a problem, as movements may be more likely to arise when existing political institutions and categories sidestep crucial political, economic, and social issues. Hence parties with well-established labels will be less likely to use petitions. Relatedly, recruitment-based petitions will be used more likely on those issues where there are fewer clear partisan differences, e.g., “second-dimension” issues like civil rights when the primary partisan divisions are over economic issues (non-partisan petitioning prediction).

Activists and organizers use recruitment-based petitions in situations of variable risk and controversy. Particularly when the risk of affiliation with a new movement is high, petitioners aware of the recruitment potential of their document will use moderate or ambiguous language in expressing their prayers (ambiguity-moderation prediction), avoiding or concealing the more extreme positions that might be taken or espoused by the organization’s leaders. (A sovereign-based theory of petitioning may also make this prediction, though excessive ambiguity may complicate the task of persuading the sovereign.)Footnote 52

In organizing movements, social status and shared esteem can serve as significant cues and motivators.Footnote 53 Analysts should be more likely to find high-status names at the top of the signatory list, with lower-status individuals placed further down. Yet since the entire process of collecting signatures cannot be controlled with precision, an activist may seek to recruit a number of high-status individuals to sign early and then engage in a more systematic canvassing campaign, using the high-status signatures to attract other high-status signers, as well as those of lower status. Status and power should be increasing in signatory list order (status-order gradient prediction). A sovereign-based theory of petitioning may also make this prediction, but within-petition inversions of the gradient should be less common in sovereign-based petitions, given that the sovereign is less likely to view the entire list.

While it cannot be known in advance which recruitment-based petitions and petitioning campaigns will be successful, the occasional success of these should be observable in data. When this occurs, petitioning patterns on a given issue should anticipate the formation of organizations and voting (anticipation prediction). The anticipation prediction argues not merely that petitioning patterns and other patterns of support will be correlated, but that the petitions come first. Whether the anticipation prediction implies causality is more complicated, not least because petitions are non-randomly assigned to localities. And petitions may simply be the first instrument that detects or aggregates pre-existing sentiment. Nonetheless, recent studies provide initial evidence for this prediction, showing how petitions for the restoration of deposits to the Second Bank of the United States, signed from December 1833 to June 1834 (before the Whig Party had been organized), predict Whig Party voting patterns as late as the 1850s.Footnote 54

Finally, to the extent that petitions build movements that express opposition to or demand change from the incumbent regime, the sovereign may find it worth her while to regulate petitioning. Opportunistic rulers will attempt to constrain petitions, especially by focusing upon the signatory list or upon the organizing possibilities it contains (suppression and constraint prediction).

The full implications of the interplay between a potentially repressive sovereign and the petitioner are beyond the scope of this paper and are the subject of ongoing research. Additional complications arise in thinking about the question of informational cascades and bandwagon effects—how and why petitions go from small to big—which also require further and more refined political analysis. Timur Kuran models the dynamic between a group of citizens who conceal their preferences from the regime and a sovereign who may wish to repress them and must choose not only if but when to do so.Footnote 55 An important reason to study strategic suppression and constraint is that these patterns reveal the recruitment potential of petitioning. Of course, political scientists confront the issue of sovereign repression of petitions most clearly and directly only once we make the move counseled here, namely that of approaching the petition as a recruitment device in the first place.

Antislavery Recruitment by Petition

The American antislavery movement is today remembered as one of the most heroic and consequential movements ever launched. By placing the issue of slavery centrally on the nation’s agenda, it set in motion processes that brought about the end of the Second Party System (with the Democrats and the Whigs opposed largely on economic issues) and, once the Republican Party adopted antislavery in the 1850s, processes that with Abraham Lincoln’s election and the Civil War culminated in the abolition of slavery itself. Yet antislavery’s early experience was one of mixed success at best. When William Lloyd Garrison began publishing The Liberator in 1831 and when, in 1833, the American Antislavery Society (AASS) was founded in Boston, American politics centered upon other issues. Garrison himself became unpopular, in part because of his radicalism. He was nearly lynched by an anti-abolitionist mob in Boston in 1835.Footnote 56 Entrenched racism still ruled the day in the North as well as the South.Footnote 57

Garrison and the AASS claimed the mantle of immediatism—the immediate, uncompensated emancipation of slaves from slaveholders, followed by full civil and political rights for black men (Garrison also wanted women’s political equality, a proposal many other antislavery leaders disagreed with). Immediatists faced a climate of deep uncertainty in their quest to find northern sympathizers. Antislavery’s most common and popular ideology (one shared by Abraham Lincoln before the Civil War) was that of colonization: emancipation with pay to Southern slaveholders, followed by “repatriation” to freed black peoples to a colony in Africa. Immediatists saw colonization as a compromise with evil, but the Northern public viewed immediatists themselves as too radical. Northerners who distrusted or even hated slavery would not necessarily sign on to the immediatist program.

Beyond this, institutional circumstances effectively foreclosed many standard methods of recruitment. Recruiting through established party organizations was not an option, because party labels provided little if any information on anti-slavery ideology during the Jacksonian era; there were numerous pro-slavery Whigs and anti-slavery Democrats in the North, and both parties endeavored to keep slavery off of the electoral and legislative agenda. Of course, third-party labels might have provided such information, but slavery-focused third parties such as the Liberty Party and the Free Soil Party emerged after, not before, the critical mobilizations of the antislavery petitioning campaign. So, too, splinter party factions in the states—the Massachusetts Conscience Whigs and the Barnburner Democrats of New York—emerged only in the late 1830s and 1840s. Antislavery leaders also lacked the patronage-based networks of the two main political parties and the networks of exchange and information that these created.Footnote 58 One of the chief challenges facing early antislavery activists, then, was locating those citizens and voters sympathetic to their cause, and creating new organizations from among these individuals.

Antislavery leaders called for a petitioning campaign to Congress in 1833 and 1834. As these petitions began to flow in, the House of Representatives, led by pro-slavery Southern Democrats, adopted the “Pinckney resolution” in 1836 and began to systematically table the petitions. This institutional procedure quickly acquired the title of “gag rule” and endured until 1844 when it was repealed.Footnote 59

The gag rule changed the politics of antislavery, but in ironic and unexpected ways. It led to much more petitioning, not less. The number of petitions exploded, going from 159 in the 23rd and 24th Congresses (right before the gag rule) to over 5,000 sent to the first congress after the gag rule, the 25th Congress (1837–1839).Footnote 60 Why did antislavery activists send petitions by the thousands to a Congress that was known to table them?

A sovereign-based perspective on petitions poorly explains this explosion. Under a Democratic House and Senate and with President Andrew Jackson protecting slavery’s advances, antislavery petitioners knew that they were unlikely to persuade the sovereign, all the more so after the gag rule meant that their petitions would not be heard. Yet Garrison, Angelina Grimké and other antislavery leaders knew that the gag rule presented them with an opportunity to make their case to the northern public.Footnote 61 Indeed, the antislavery petitioning campaign was coordinated in common with the Liberator and the AASS, and consciously harnessed and encouraged the efforts of newly organized and activist women.Footnote 62 A recruitment-based perspective provides unique insight into several aspects of these petitions and the organization that followed them.

Antislavery petition prayers (ambiguity/moderation prediction).

While Garrison and the AASS were committed to immediatism, their early petitions called for more moderate measures. The most common early prayer was for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia; over 75 percent of petitions sent to the 23rd and 24th Congresses (before the gag rule) embedded this request in their prayer. Prayer for slavery’s abolition in Washington, D.C., focused on a jurisdiction where the national government clearly had control, thereby avoiding states rights’ debates that had flared up during the nullification crisis just a few years earlier. From the District of Columbia petitions, antislavery organizations started circulating others calling for the interdiction of the interstate slave trade, again sidestepping states’ rights and focusing on Congress’ powers under the interstate commerce clause.Footnote 63

When the gag rule passed, the antislavery organizers had another popular theme on which to petition: the repeal of the gag rule itself. Defending the right of petition enshrined in the First Amendment, immediatist and Garrisonian antislavery leaders could claim the mantle of fidelity to the Constitution, casting Southern Democrats and slaveholders as oppressive authoritarians opposed to basic traditions of American liberty. From the 25th to the 27th Congress (1837–1843), almost one in four antislavery petitions (23.4 percent) called for gag rule repeal. Only calls for abolition of slavery in Washington, D.C., were more common in antislavery prayers (36 percent) during the same period.

Antislavery petition transmission.

If antislavery petitioners hoped to persuade their own congressional representative, as a sovereign-based perspective would suggest, they behaved very inefficiently in doing so. Nearly half of antislavery petitions were sent to a member other than the one representing the district from which they came. As an example, four in ten antislavery petitions from New York were sent to either John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts or William Slade of Vermont. Almost half of petitioners from Michigan (48.4 percent) and New Jersey (46.8 percent) were sent to these two out-of-state members. These patterns persisted in states with emerging antislavery elite constituencies such as Connecticut (45.9 percent) and New Hampshire (34.9 percent).

Recruitment dynamics and the gag rule explain these out-of-state transmissions. Antislavery organizers knew that Adams and Slade would attempt to read the petitions on the floor under the gag rule,Footnote 64 and they could explain to signatories that a sympathetic member and an ex-president would be receiving them. Accordingly, petitions were more likely to be sent to Adams when they involved the gag rule (odds ratio = 1.51; p < 0.001) or national-level issues such as the interstate slave trade (odds ratio = 1.27; p = 0.001).

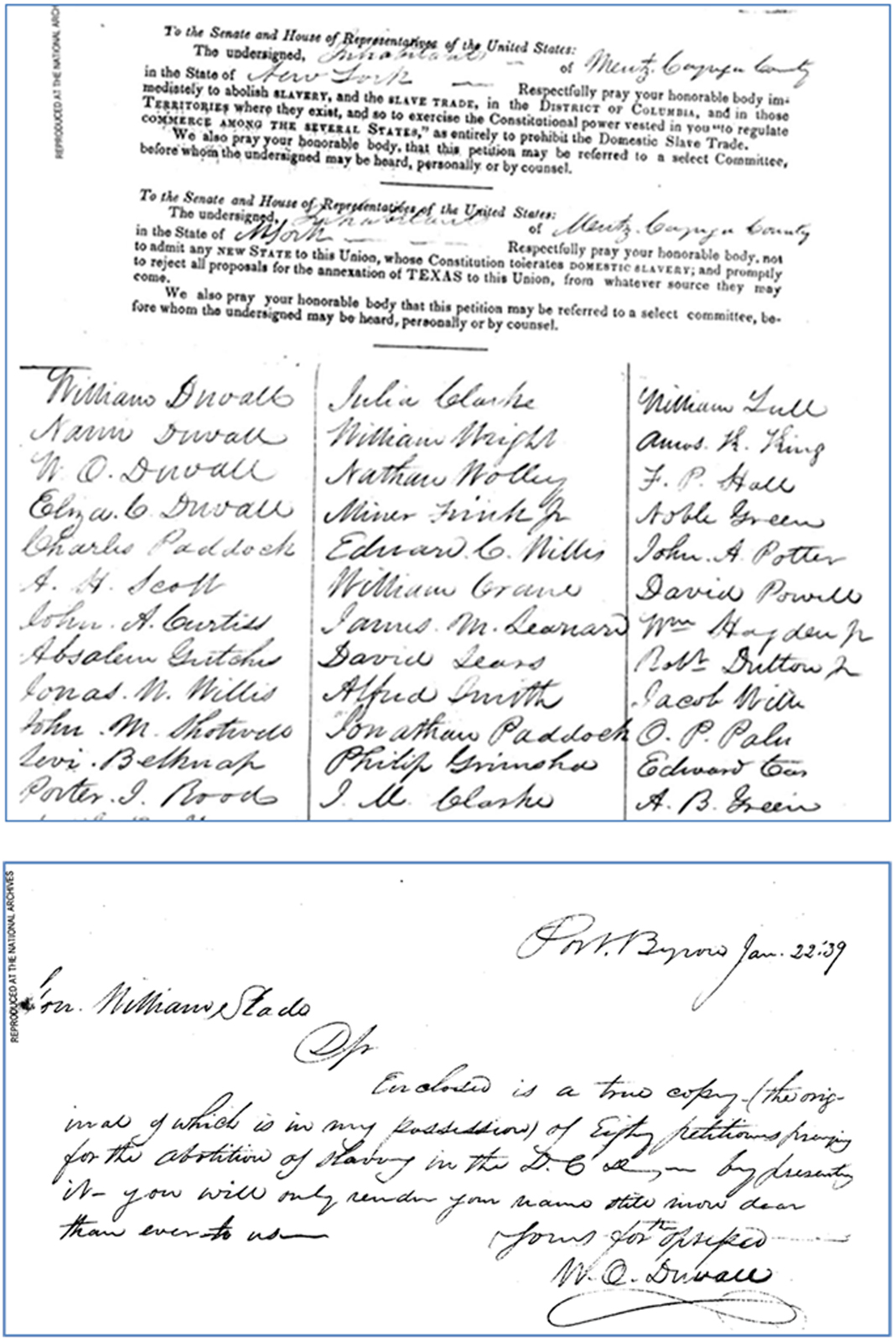

However and to whomever petitions were sent, antislavery activists often made multiple copies of their petitions or had signers affix their names to two or more. Only one of these would be sent to Washington, while the other would remain with the local antislavery society or would be posted publicly in its community of origin as a demonstration of public support (original kept, copy sent prediction). One example comes from the submission of Cayuga County, New York antislavery activists led by William Duvall (refer to figure 1). The petition sent to Congress had signatures in identical manuscript (evidently that of Duvall’s), with Duvall’s accompanying note that he had kept the original copy in his possession.

Figure 1 Cayuga County, New York antislavery (1839) petition with signatures in identical handwriting, with a note explaining that the original is being kept in local possession, with a copy sent to Congress

To send a petition with identically written signatures to the sovereign invites claims of illegitimacy, and throughout the antebellum period slavery’s defenders in Congress repeatedly held up examples of such petitions, denouncing the antislavery movement as a fraud.Footnote 65 A recruitment-based perspective, however, uniquely explains why the copied signatory lists were sent and the originals retained. The audience to be persuaded was not Congress, but the potential joiner in Cayuga County. And the best copy could be kept as a record by local antislavery societies for display or for recordkeeping.

Anticipation and non-partisanship.

Antislavery petitioning surged at a time when the two major parties did not split on slavery.Footnote 66 No antislavery party was formed in the United States until the dawn of the Liberty Party in 1840. Both the growth of the Liberty Party and the greatest expansion in antebellum antislavery societies came after the petition mobilizations of 1837–1839, not before. In tables 1 and 2, I present simple regression evidence for this proposition.

Table 1 The county-level association between AASS chapter organization and petitions to the U.S. House, New York State

Note: Dependent variable is log of one plus AASS chapters in county i in 1838.

Note: Dependent variable is change in log of one plus chapters in county i from 1836 to 1838 = [ln(1 + chapters_1838) – ln(1 + chapters_1836)].

Table 2 Regression of Liberty Party presidential vote [Birney] (1844) upon petition characteristics, 23rd–28th Congresses [OLS regressions, each Congress’s petitions used for separate battery of regressors]

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses; petition-related coefficient estimates in bold if associated p < 0.05 (two-tailed test). Dependent Variable is % county vote for James Birney (Liberty Party Candidate) in 1844, expressed in tenths of percentage points.

Table 1 presents evidence showing that, at the county level, antislavery petitions are associated with the county-level formation of AASS chapters in the critical state of New York, even controlling for past chapter-level aggregates. In table 2, I examine the county-level vote for Liberty Party presidential candidate James Birney 1844, at the very height of the Liberty Party’s power, namely when Birney’s 5,000 votes in the state of New York plausibly threw the election that year to James K. Polk instead of Henry Clay.Footnote 67 Focusing on the Birney presidential vote controls for candidate quality across constituencies and represents the height of anti-slavery party mobilization. As predicted, petition signatories per capita from the 24th (1835–1837), 25th (1837–1839), and 26th (1839–1841) Congresses statistically anticipate Birney’s vote in 1844. Strikingly, the petitions from 1837–1839 predict Birney’s county-level 1844 vote (R-squared = 0.33) 37 percent better than do antislavery petitions from the very years that Birney was running (28th Congress, 1843–1845; R-squared = 0.24). The networks and mobilization effected during the critical antislavery petition drive of 1837–1839 figured more powerfully than even contemporary activity in driving the central electoral success of the first antislavery party.

Recruitment of Protestants by Cahier, Supplique, and Requête in Sixteenth-Century France

The emergence of Protestantism in sixteenth-century Europe remains one of the most epic political, cultural, and religious transformations of world history. Starting with a core set of adherents in Germany, the revolt against Roman Catholicism quickly spread to other European regions, including France. French Protestants and reform-minded Catholics rather quickly committed to the tenets of Jean Calvin, a Parisian-based theologian who moved to Geneva in 1534 and who began sending missionaries to France in 1555.

The literature on Protestantism in general and Calvinism in particular is immense, but several common themes are important for understanding the recruitment problem Protestants faced. Protestants objected to certain features of the Roman Catholic Mass, not least the doctrine of transubstantiation in which the prayers of the presiding priest transformed the bread and wine literally into the body and blood of Jesus Christ. Protestants felt that Christ had been sacrificed once and for all time; the Eucharist could be nothing more than symbol. Yet the institutional critiques of early European Protestants figured every bit as importantly as their doctrinal misgivings. Roman Catholicism created an entrenched hierarchy of priests and bishops whose actions and offices Protestants found incompatible with Scripture. Protestants also criticized the institutions of civil society, including brothels, which were under increasing attack in the 1550s and were prohibited universally in the Edict of Orléans of 1561.Footnote 68

Sixteenth-century Protestantism confronted a milieu with many potential “friends” and many potential “enemies.” Such was the fluid and charged nature of the time that it was not clear who was sympathetic and who was antagonistic. Currents of Catholic reform inspired by the writings of Erasmus were interwoven with Protestant animosity, as some disaffected Catholics thought the Church capable of significant change. Theological cleavages among Protestants—Calvin and his followers, as well as followers of Luther and Zwingli—rendered the Protestant recruitment problem harder. Some emphasized institutional issues over doctrinal issues, as Protestantism attracted French subjects concerned about moral corruption in local and national institutions. These divides of belief and emphasis meant that when reformers found sympathizers, the latter were not necessarily going to become committed Protestants. Many potential Protestants were unsure of the doctrines and institutional preferences of Calvin’s followers. Some Erasmian Catholics wished for toleration while many others did not.Footnote 69

The institutional context of early modern France made the recruitment dynamics of early French Protestantism even more complicated. At a time when decades of war and turnover had unsettled many of Europe’s monarchies, Protestantism’s institutional critiques threatened not only those with clerical authority but also officers of the Crown. In ancien régime France, a critique of the wealth and privilege of the clergy could enable a critique of the three estates system—the clergy, the nobility, and the populace—that supported the Crown. Accordingly, the Crown and many French elites saw in Protestantism a lurking form of rebellion. Even Michel de l’Hôpital, chancellor of France under Kings Francis II and Charles IX and a high elite favorable to toleration of Calvinists, acknowledged in 1560 the common belief that the “principal cause of sedition is religion.”Footnote 70

A sort of break for French Protestants came in 1560, when after the death of King Henri II the year before, the young Francis II was installed as King. Kings in their “minority” years—where their powers were effectively exercised by their mother, the Queen Regent, and various royal officials—ruled with fragile claim on power, and Francis was no exception. To solidify his rule and to raise funds for the operations of the Crown, Francis II had called an Estates General in the summer of 1560. In this procedure various estates, first regionally and by towns, then in common at a site selected by the king, would draw up lists of complaints (doléances) and requests (requêtes) to be compiled into a cahier général or cahier de doléances. These cahiers were then presented to the King, whose responses could affirm existing laws or announce new ones.Footnote 71

From the very death of Henri II, French Protestants began to use petition-like institutions—not only the cahier, but also the supplique, the requête and the oral harangue—to make doctrinal and political claims upon the Crown. Protestants presented an early requête to the Assembly of Notables at Fontainebleau in August 1560 (refer to figure 2 for a reprint).Footnote 72 Another harangue was delivered to Charles and his royal council at Poissy in 1561. In these appeals and laments, Protestants called for “the reformation of religion, as much in doctrine as in mores,” and championed “liberty of the Gospel” in tandem with “political liberty” while decrying the “murders and oppressions committed daily in this kingdom” against their members, as “no one should be harmed or pillaged (injurié ne fouillé) for the true service of God.”Footnote 73

Figure 2 – Protestant requêtes to French royal council, 1560

The debates that ensued throughout France in 1561 were conducted in a tense environment, rich with possibility but equally loaded with mortal risk. Calvin’s followers attempted to recruit locally, and Protestants’ requêtes and cahiers to a town’s governors (consuls) or municipal council reinforced their evangelism.

A strikingly rich interplay between the cahier process and Protestant conversion took place in the southern French town of Nîmes. According to historian Allan Tulchin, Nîmes eventually became “the heart of Protestant France,” but in the late 1550s, Protestant ministers were having difficulty attracting the town’s higher-status inhabitants. One Catholic noted in March 1561 that “an air of reform, which the preachers of the new religion made seem necessary, seduced some; the license which it encouraged corrupted the others, and in the uncertainty, or, more accurately, the ignorance about the Catholic religions and the Reformed religion that prevailed, people did not know which of the two to cleave to, and which pastors to follow.”Footnote 74

Leaders of the small Protestant community in Nîmes drew up a cahier in March 1561 and presented it to a meeting of the town’s consuls. The signatories of the cahier publicly attended the meeting as “named citizens.” Their cahier would prove especially forceful in the Protestants’ mobilization. It called for a range of Protestant demands but also carried a range of complaints and requests that reform-minded Catholics could also support. Well beyond “the reform of religion,” these included a call for the Church to contribute to the reduction of the Crown’s debt (through handing over a significant portion of the benefices of the clergy), the regulation of royal expenses as a means to limit future debt, and the limitation of judicial abuses. Consistent with the recruitment-based model’s prediction of ambiguity and avoidance of extreme positions (ambiguity-moderation prediction), the Nîmes cahier “carefully skirted certain controversial religious questions,” Tulchin remarks, “so that Catholics, particularly those of an Erasmian or reform-minded stripe, could sign it in good conscience.”Footnote 75

Introduced to the conciliar government at Nîmes on March 15, 1561, the Protestant cahier was signed by 133 citizens who attended the meeting in person. So popular was the cahier that 188 additional men quickly signed it after its initial presentation.Footnote 76 Tulchin examines these signatures and notes a high proportion of Nîmes nobles who signed the cahier, a crucial development in the development of the Protestant movement which had lacked support among the nobility. Tulchin argues persuasively that “the cahier’s ideology was wildly popular” and that its arguments were deeply persuasive to Nîmes citizens across a range of classes and occupations, including, probably, some Catholics who signed.Footnote 77

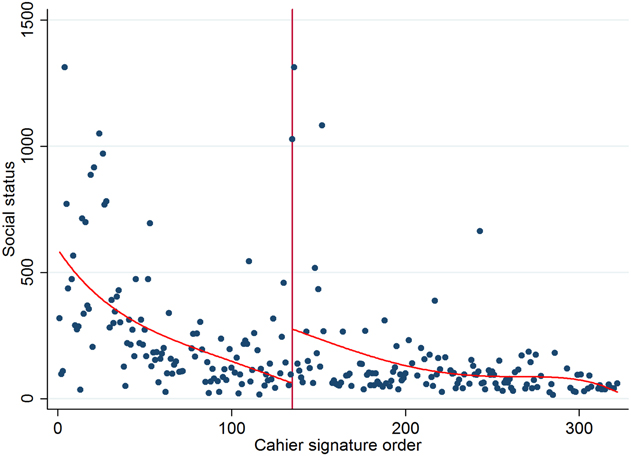

While the cahier’s arguments undoubtedly carried weight, its signatures may also have persuaded uncertain citizens of the town. Consistent with the status-order gradient prediction of the recruitment model, higher-status citizens were distinctly more likely to appear earlier in the signatory list in both the first and second waves of the Nîmes cahier. The presence of high-status names in the first wave of signatures may have helped persuade later possible signatories.

Table 3 presents regression evidence showing the relationship between measures of social status and the order of signatures on the Nîmes cahier of 1561. The plot in figure 3 uses a measure of social status developed by Allan Tulchin from dowry data.Footnote 78 The regressions use this measure and a binary indicator of whether the signatory was listed as a noble or as a “master” (maistre) in the main published summary of the signatory list.Footnote 79 The first title designated membership in the second estate, while the second denoted the status of authority in labor and economic relationships and also implied some ownership of capital.Footnote 80 Across these regressions, a negative and statistically significant relationship between status and signature sequence is observed, such that the higher the status of the signatory, the earlier he signed the cahier. A one-unit increase in the logarithm of signature order is associated with a 38 percent decline in the odds of being noble in the first wave and, for the second wave, an 81 percent decline in the odds of nobility. Similarly, a one-unit increase in the logarithm of signature order is associated with a 93 percent decline in the odds of being a master for the first wave, and for the second wave, a 44 percent decline in the odds of mastership. Finally, a ten percent increase in signature order is associated with a 4.3-percent decline in status as measured by Tulchin, and a 3.8 percent decline in status in the second wave.Footnote 81

Table 3 Status-order gradient regressions for Nîmes Protestant cahier, 1561

Notes: Original cahier data from Ménard (1753), status measures computed from dowries by Tulchin Reference Tulchin2010. Noble and maistre indicators calculated by author from Ménard (Reference Ménard1753 [Preuves]: 268–69, 281–82). OR = Odds ratios reporting of relevant coefficients; null hypothesis for odds ratios is that the coefficient is equal to one. Model is identical to the logit model reporting coefficients only. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

Figure 3 Social status by signature order, first wave and second wave, Nîmes Protestant cahier of 1560

Note: Status measure computed by Tulchin Reference Tulchin2010.

A remarkable pattern among the Nîmes cahier signatures is that the status-order gradient is stronger within the waves than across them. While the second wave of signers had lower status than the first, this relationship is swamped by the status hierarchies within waves (table 3).Footnote 82 Put differently, the second wave did not commence with a group of people whose status was uniformly lower than those who had signed in the first wave. The two-wave character of the signatory list of the Nimes Protestant cahier of 1561, with its jump in status from the end of the first wave to the beginning of the second, is more consistent with a petitioning process in which the relevant audience includes not only the sovereign (the Crown) but also the next possible signatory. The next possible signatory, after all, could become the next convert. Protestant recruitment by cahier expressed a logic of evangelism. Footnote 83

In the aftermath of the cahier and the Estates-General at Poissy in December 1561, the Protestant communities in Nîmes and other French towns grew, and so did their petitioning.Footnote 84 The saga of Protestantism would continue, but the Estates-General under Charles IX marked a high point, with perhaps as many as two million converts by 1561. As Tulchin demonstrates using his rich data, moreover, signing of the cahier appears to be predictive of later leadership and membership among Nîmes’ Protestant community (anticipation prediction).Footnote 85 The following decades would witness epic religious violence,Footnote 86 and while most of the violence was committed by the Catholic majority against Protestants, in Nîmes in 1567 and 1569 and La Rochelle in 1568, the Protestant majority massacred the Catholic minority.Footnote 87 The status of French Protestants improved greatly with the Edict of Nantes (1598), a decree for Calvinist rights issued by Henri IV and a watermark in the history of toleration.

Later French Protestants would also use petition-like institutions to advance their claims, often using national meetings of ministers (synods) to drawn up new requêtes and cahiers.Footnote 88 Assembling at Charenton in the 1620s, a synod of ministers made several claims upon the Crown in a cahier, including a call for the liberty of general assembly among ministers, but the young King Louis XIII decreed that further meetings would have to include a Royal Commissioner present, in part as a check upon the organizing tendencies of the Protestant ministers and their petitions, and to monitor their discussions. Further cahiers of Protestant ministers followed synods in 1602, 1604, 1611, 1615, 1623, 1625, 1631, 1637, and 1660.Footnote 89 In some sense, the ministers’ synods had become the functional meeting of an estate (not unlike those of the first estate, the Catholic clergy, from which cahiers also issued). It is all the more telling (suppression and constraint prediction), then, that Louis XIII wished to have a minister of state accompany synod proceedings from 1623 onward. When under Louis XIV the Edict of Nantes was revoked and Protestants were once again subject to institutionalized persecution, they again turned to petitions to make their case against the policies of the Crown.Footnote 90

The Logic of Signatory Repression—The English Restoration and Other Examples

The rich organizing possibility embedded in the directed petition and its signatory list comes with risks for those in power. Rulers can benefit greatly from flourishing petitioning practices—learning about the wishes and grievances of the governed, bolstering legitimacy by listening to these claims and responding to them—yet petitioning’s recruitment value can create organized opposition and plausibly threaten order. That rulers have sought to restrict petition and organization is one plausible explanation for why the framers of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution explicitly stated the right to petition for redress of grievances, and placed this right immediately after the right of peaceful assembly.

One of the most striking and illustrative examples of petition suppression comes from the nation that did so much to entrench norms and institutions of executive and legislative petitioning: England. In the 1640s, during the very crucible of the formation of the public sphere,Footnote 91 petitions combined with pamphlets and other forms of print culture to constitute a domain in which basic questions of politics, institutions, and religious faith could be debated openly. Yet the liberality of discourse meshed with a level of political turbulence yet unseen. While European monarchs had been occasionally assassinated (the French sovereign Henri IV in 1610) or overthrown by rival elites, in 1640s England the Parliament raised a rival army to that of the king and the two sides prosecuted a civil war. The end result forever changed the history of monarchy in England and Europe: the conviction and the public, legitimated execution of a sovereign monarch, the Stuart King Charles I in January 1649, followed by the abolition of the English monarchy altogether in March.

In 1660 the English Parliament re-established the office of King, and the Parliament that served under its new occupant (Charles II), known as the Cavalier Parliament, was decidedly more monarchy-friendly than its predecessor. The Cavalier Parliament took aim at some of the central accomplishments of its predecessor, eliminating the Triennial Act (by which elections for Parliament were to be held at least every three years) and passing the Oath of Allegiance Act for all officers. Yet one of the most far-reaching laws passed by the Cavalier Parliament, one whose enforcement persisted deep into the nineteenth century, was the Act Against Tumultuous Petitioning in 1661.Footnote 92 Its essential text stated:

That no person or persons whatsoever shall from and after the first of August One thousand six hundred sixty and one solicite labor or procure the getting of Hands or other consent of any persons above the number of twenty or more to any Petic[i]on Complaint Remonstrance Declarac[i]on or other [Addresses] to the King or both or either Houses of Parliament for alterac[i]on of matters established by Law in Church or State unlesse the matter thereof have beene first consented unto and Ordered by three or more Justices [of] that County or by the Major part of the Grand Jury of the County or division of the County where the same matter shall arise at theire publique Assizes or Generall Quarter Sessions or if arising in London by the Lord Maior Aldermen and Commons in Common Councell assembled.

The Act of 1661 did not prohibit petitions but rather subjected them to regulation. Consistent with the suppression and constraint prediction of the recruitment-by-petition model, this regulation targeted not the prayer but the signatory list, as no more than twenty signatures could be attached to any single petition without prior authorization from multiple justices of the county from which it originated, from a grand jury in that county, or from the elites of London. The Act further limited the assembly of persons presenting a petition to the Crown to no more than ten. Any substantial signatory list now required pre-approval. This plank of the law created incentives for petitions with smaller signatory lists.

The historical context and language of the bill point to grave worries among Crown officials and the Cavalier Parliament that petitions were being used to organize opposition to the King and Parliament. A thoroughly elite measure, the bill started in the Lords and was later sent to the Commons. It came at a time when petitioning in many forms was on the rise, not least because there was a flesh-and-blood occupant in the most important office in the English imperial world to receive them. Petitioning had waned considerably during the interregnum, and the recreation of the monarchy released a host of pent-up demands and complaints. Immediately upon Charles II’s ascension to the Crown in 1660, Native American tribes in Connecticut colony began to ask openly whether they could end-run the colonial legislatures—which had alone received their petitions in the 1650s—and petition the Crown directly again, as they had under Charles I.Footnote 93 An analysis of petitions to the Crown in 1661 and 1662 suggests that many former Parliamentarians and allies of different factions in British politics were attempting to test their relationship to the newly restored monarchy and its institutions. Parliamentarians in prison began requesting release, and those who had escaped imprisonment supplicated heavily for the return of their lands, so much so that Charles II in April 1660 established a commission to deal with the land petitions.Footnote 94 In the eyes of the Restoration monarchy, some of the most worrisome petitioning campaigns were coming from those committed to parliamentary sovereignty and religious radicals. Petitioners from nineteen different counties sent in demands for a “free Parliament” in 1660, and the petition from Oxfordshire reportedly had more than 5,000 signatures attached.Footnote 95

The Act’s particular language also gives clues to its motivation. The first paragraph of the statute identified the “sad experience by which Tumultuous and other Disorderly solliciting and procuring of Hands” upon petitions had served the ends only of “Factious & Seditious persons.” The word “tumult” had exploded in use during the Civil War, and the concept was alternately praised (by religious radicals who wanted “a tumult for the Gospel”) or lamented (by royalists who saw the idea as akin to sedition), depending on one’s perspective. The Cavalier Parliament, in the Oath of Allegiance Act, forbade any officers of the Crown from taking any action “to Discharge any of his Majesty’s Subjects of their Allegiance and Obedience to his Majesty; or to give Licence or Leave to any of them to bear Arms, raise Tumult, or to offer any Violence or Hurt His Majesty’s Royal Person, States or Government.”Footnote 96 Anglicans saw the risk of “tumult” in the various meetings of Quakers, Anabaptists and Catholics.Footnote 97

Hundreds of pamphlets from the period, meanwhile, celebrated or disdained tumult. In his sermon A pillar of gratitude humbly dedicated to the glory of God the honour of His Majesty (1661), the minister John Gauden (newly appointed Bishop of Exeter in the Restoration) compared two modes of non-conformity, the “meek” sort and the “violent, tumultuous” sort. The spirit of “tumult,” in Rev. Gauden’s reading, gave rise to “Separation, Schism and Sedition,” and he contrasted it with that of “Learning and Loyalty, Meekness and Moderation.” The Oxford arch-deacon Barton Holyday, former chaplain to Charles I, argued in Against disloyalty: fower [four] sermons preach’d in the times of the late troubles (1661) that tumult in religion and other realms risked grave sin, as rebellion amongst men was not far from rebellion against God. And the royalist Roger L’Estrange, in his pamphlets Interest mistaken (1661) and State-divinity (1661), compared the mode of tumult to that of rebellion, sedition, and that deeply Anglo-American and republican worry: “faction” in the state. Such a note of faction was also used in the preamble to the Act Against Tumultuous Petitioning (refer to the quoted text).

Tumult thus became a quasi-factional term in the Restoration. Discord sown by opponents of the Stuart regime was “tumultuous” when it presented an organized threat beyond the individualized voice. In the end, however, the 1661 Act required preclearance only of potentially “tumultuous” petitions, and the criterion of organization was central in defining what was tumultuous and what was not. If a petition had more than twenty signatories, or if ten or more subjects presented it, it was tumultuous. In a world where petitions were apparently being used to recruit,Footnote 98 and without attention for whether the sovereign responded to them, rulers in the wake of the Civil War could fear the political technology of the petition’s signatory list.

Later English monarchs and Parliaments relied upon the tumultuous petitioning statute, and it was hotly debated during one of the most intensive mobilizations in the history of petitioning, the Chartist Movement of the 1840s, during which signatures totaling more than 4 million were affixed to labor movement petitions.

In contemporary politics, rulers in diverse regimes commonly regulate petitions. The journalist Lawrence Weschler has conducted fascinating journalistic inquiries in Uruguay on citizens signing anti-amnesty petitions for those who had tortured government opponents under an earlier regime.Footnote 99 Those who signed these petitions were subject to repression, particularly when police systematically reviewed the signatory lists. Authorities also scoured citizens’ earlier histories of petition signing, and the regime took systematic measures to make petitioning more difficult. A recent study of the Chavez government in Venezuela also finds a drop in earnings and employment for those who signed a large anti-Chavez petition (the Maisanta),Footnote 100 though Chavez was possibly less concerned about the recruitment value of the Maisanta and more concerned simply to identify his enemies.

The Petition as Political Technology: Ladders of Engagement in a Digital Era

In the twenty-first century, new forms of digital petitioning have come to predominate, creating a dynamic of “digitally enabled social change” and “connective action.”Footnote 101 These petitions circulate by means of electronic mail networks, social media, and advertisements, and citizen can sign them with the click of a button. Like many of the historical petitions I have described here, digital petitions are commonly sponsored and subsidized by political organizations. These organizations approach the digital petition explicitly and consciously as a technology of recruitment. The political scientist David Karpf describes how political organizations view petition signing as a lower rung on the progressively rising “ladder of engagement” by which people first sign a petition and then take other, often more costly and involved, actions on the organization or cause’s behalf.Footnote 102

While digital petitioning organizations vary considerably,Footnote 103 they generally maintain a comprehensive database of digital petition signatory lists for information and further recruitment.Footnote 104 They monitor which petitions have met with success and which with failure. Those petitions and issues that exhibit greater likelihood of generating more participation are termed more “growthy.”Footnote 105

Historical-institutional analysis shows that these possibilities are not unique to the digital petition. Even in the absence of locating information—whether geographically in the sense of a home or work address, or electronically in the sense of an e-mail address attached to a domain name—a name is recognizable information that can be linked with other data.

The reliance of digital petitions upon an e-mail address offers both an advantage and a weakness. The advantage is that the electronic address can be collected and canvassed repeatedly, spread widely at little cost.Footnote 106 The disadvantage is that it is far easier to change one’s e-mail address that it is to change one’s postal or geographic address, and far easier still to change these than it is to change one’s name. And at least one psychological study concludes that the sense of commitment to honesty and follow-through from a digital signature does not match that carried by a handwritten signature.Footnote 107 Relatedly, a growing literature suggests that extended electronic activism is highly limited.Footnote 108

In other ways, recruitment by digital petition exhibits many of the same patterns as historical recruitment by paper petition. Consistent with the recruitment model and the anticipation prediction, one study finds that signing an e-petition is a gateway to further participation.Footnote 109 And the preponderance of “post-materialist” themes (identity politics as opposed to redistribution) on many electronic petitions is consistent with the non-partisan prediction of the recruitment model,Footnote 110 insofar as for issues of redistributive politics where the parties usually take clearly diverging approaches, mechanisms of partisan and ideological recruitment may suffice, making petitions less effective or necessary for these ends.

The fact that digital petitions embed and institutionalize recruitment allows political scientists to cast these developments in a richer historical light. The claims made for the recruitment potential of e-petitions have been thoughtfully adduced, but many of these claims could have been made centuries ago about paper petitions. Then as now, petition signers could climb a ladder of engagement, and then as now, certain petitions were more “growthy” than others. Then as now, signatory lists were kept as implicit or explicit databases. A historical comparison of paper and digital petitions suggests that the petition itself is a technology regardless of whether the signature is accompanied by an e-mail address or other electronic locator.

The electronic petition renders much more explicit and formalized what has been there as an embedded dynamic all along, namely the technology of recruitment. The digital petition has thus routinized a much older function, though without the critical process of human canvassers using face-to-face appeals. Indeed, one might worry that in this performance of routinization, the digital petition so heavily emphasizes recruitment that it may dilute the legitimacy of the institution itself. Sites like Change.org and MoveOn.org generate so many petitions that there is no possibility that all of them will be met with a response. It is perhaps for this reason that these sites advertise to their readers that their petitions are successful in many cases.Footnote 111 An earlier generation of petition generators did not need such advertisements (or at least did not need them as much), because the norm of petitioning was one in which a response was expected.

A historical-institutional perspective on the longue durée of recruitment by petition suggests caution in the petition’s interpretation and in its use. While political activists consciously and prospectively use petitions today for organizing, the petitioners from medieval regimes to modern democracies may well have learned about petitioning’s recruitment function as they canvassed petitions originally meant for other, more expressive purposes.Footnote 112 To propose that older petitions themselves were created or launched with recruitment in mind risks a functionalism that betrays historical understanding.Footnote 113 So too, a historical-institutional perspective should lead both analysts and citizens to greet with skepticism any assumption that petitions—whether signed on paper centuries ago or signed electronically now—represent “grass roots” activity.

Finally, the intensive use of petitions to recruit and organize risks undermining the legitimacy of the petition itself. If petitions are known to be used just for recruitment purposes, such that every signature is followed by little more than another series of asks, citizens may sour on petitions as just another form of advertising and intrusive data collection. Petition signers from medieval to modern times probably understood that they were being recruited into something broader, but they also saw meaning and value in the petition’s expressive purposes. In addition to their expression of self, many of these petition signers felt that their community and their Creator were watching. Recruitment by petition does not erase, but relies upon, the intrinsic and expressive value of a signature.

Conclusion

The recruitment-by-petition model identifies a strategic logic that animates many petitions and petitioning campaigns. Petitions do far more than convey information and emotion to the sovereign who receives them. They have other audiences, both local and general, whose importance is often sufficient to drive the petition itself.

A recruitment-based interpretation of petitioning offers possibilities for mathematical formalization and experimental testing—one can imagine assigning experimental variation in petitioning campaigns and then later tracking recruitment to affiliated political organizations, for instance.

Both the study of social movements and the study of participation would benefit from approaching petitions more as the institutional particularities they are, in addition to activities that complement protesting, voting, or donating money and time.Footnote 114 Scholars of participation would better recognize that petitions entail solicitation and subsidy by the activists and groups who sponsor campaigns. The “grass roots” and “politics from below” can never be viewed in isolation from the organizing agents (sometimes “elites,” sometimes not) who fashion argumentation and signature gathering.

Petitions appear to be surging in use. From electronic petitions and petition-and-referendum institutions in the United States, to movements in Latin America, China, Europe, and other regions, their presence is ubiquitous in modern politics. Citizens in apparently rigid authoritarian contexts frequently use petitions, whether the over 10,000 Cuban dissidents who signed a pro-civil-liberties petición in 2002, hundreds of Chinese dissidents who have affixed their name to Charter 08, or academics in Turkey whose petition signatures led to their arrest and, after international outrage, their release.

Just how common is recruitment by petition? Just how common is petitioning itself? In the aggregate, does it serve the weak or the strong? Does petitioning complement or substitute for other forms of political activity? How often do petitions meet with success in their embedded requests and complaints, and what institutional and political features are correlated with success and failure? Despite the vast deployment of petitions today and their centuries of history, scholars have no systematic answers to these questions.