Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 June 2004

Contrary to conventional wisdom, nationalism remains alive and well across an increasingly integrated Europe. While most nationalisms are not violent, the desire for greater national voice by both states and groups continues to exist in both the East and the West. As the European Union deepens and widens, states and groups are choosing among four nationalist strategies: traditional, substate, transsovereign, and protectionist. The interplay among these nationalisms is a core part of Europe's dynamic present and future.

The collapse of communist regimes in the extraordinary series of events of 1989 gave Central and Eastern European societies an unprecedented opportunity to redefine themselves as well as their relations with each other and the broader international community.1

We presented earlier versions of this paper at the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association and the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies in 2002.

In fact, the “national” idea (i.e., the idea that social and political organization should center on nation building and national sovereignty) became the most powerful common characteristic of postcommunist transitions, overshadowing alternative social and individual organizing principles, such as liberal democracy, universalism, nonnational forms of regionalism, and pan-Europeanism. Although all of these alternatives were part of the repertoire of transformation, none became as powerful as the national principle. Each of the three communist federations (Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia) fell apart along national lines, and most unitary states began asserting national sovereignties in various forms—if not at the beginning of postcommunist transformation, then later, as the prospects of European integration became more real.2

Numerous sophisticated, multidimensional explanations have been published in recent years for the pervasiveness of nationalism in the postcommunist world—emphasizing the role of institutional legacies, manipulative political elites, and events and human actions that created a tide of nationalist mobilization. See, e.g., Brubaker 1996; Bunce 1999; Snyder 2000; Beissinger 2002; Tismaneanu 1998.

Naturally, each society in Central and Eastern Europe had different initial conditions for nation building after the collapse of communism. For instance, Latvia and Estonia had large ethnic Russian populations, whose status was of concern to the Russian government; the Czechs had no significant national minorities within or outside their “homeland” (i.e., Czech lands proper); and the Hungarian government concerned itself with Hungarian minorities across the border in several countries. Under such diverse conditions, nation building (or nation consolidating) took different forms and had different consequences, but thinking in terms of “nation” and “national sovereignty” remained prevalent across post-communist Europe.

Despite the visibility of the violent Yugoslav conflicts, in most cases nationalism has been peaceful and coupled with other social activities, such as the emergence of so-called civil society—an especially salient process in societies that previously had limited civil organizational activity. At the same time, nationalism always entails arguments about the definitions of nation, homeland, and self-government, and therefore most contemporary scholars assume that nationalism is a potentially dangerous, destabilizing political activity.3

See, e.g., Haas 1997; Haas 2000; Beissinger 1996; Hechter 2000. For a discussion of the history of such contestations in the southeastern part of Europe, see White 2000.

Many Western scholars and policy makers have believed that democratization and European integration will eventually render nationalism obsolete. Indeed, while a number of impulses have led both the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to pursue a project of enlargement in the East, a core element has been the notion that the rational, pluralist economic and security community that the West created and strengthened during the Cold War could help stabilize the East in the post–Cold War world. The benefits of joining this Western community would lead Eastern governments to adopt EU and NATO norms and principles and ensure that governments in places like Warsaw, Prague, Budapest, Bucharest, and Tallinn behaved “responsibly.”4

On the impulses behind the extension of the Western zone, see, for example, Goldgeier and McFaul 2001. For a good overview of the West's view of the East, see Schöpflin 2000.

See Hobsbawm 1990; Beissinger 1996. Postmodern perspectives on nationalism also predicted the disappearance, or fragmentation, of identities characteristic of the modern period—among which nationalism figures prominently. See Smith 1998. For a different view, see Nodia 1994.

Nationalism is not fading away, and what makes it interesting in the new Europe is how it is changing and the ways in which states or groups may come to alter their nationalist strategies over time. The presence of the European Union is an important part of these calculations. European governments and societies are participating in a debate over the shape of the Union after enlargement that begs broader theoretical questions: What happens to nationalism when sovereignty becomes “shared” and the flow of people and ideas accelerates across existing state boundaries?6

Does the traditional face of nationalism—defined as “primarily a political principle, which holds that the political and the national unit should be congruent”—change substantively?7Gellner 1983, 1.

We argue that regional and global integrative processes significantly change domestic and international opportunity structures for nationalist pursuits of political-cultural coherence, but do not render them obsolete. Rather, old and new forms of nationalism coexist and mutually challenge and reinforce one another in a complex process that shapes the chances and direction of integration.8

Beissinger 2002.

Aspirations for institutional forms that enable cultural reproduction of “nations” on the territory of “national homelands” remain a shared element of all contemporary nationalisms. What changes is the way different agents go about achieving or preserving cultural ownership of the national territory. These paths are fundamentally altered by integrative processes. At the same time, integrative processes are also shaped by old and new forms of nationalism.

In this essay, we propose a theoretical framework for thinking about the relationship between nationalism and integration as a dynamic process. We are interested in nationalism as an enduring institutional strategy that takes various forms in the pursuit of reproducing self-governing “nations.”9

Brubaker's (1996) notion of “nation” as an institutionalized form is useful in understanding this process.

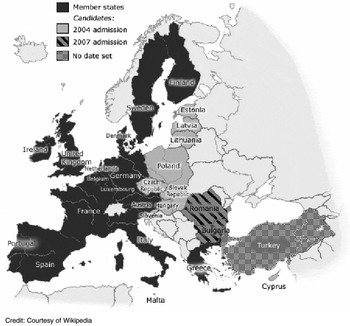

But the traditional nation-state strategy is only one of a number of ongoing national pursuits in contemporary Europe. We outline four types of nationalism found among current and future EU members, groups within these states, and other European states that are in line for EU membership later in this decade. (See Table 1.) Based on its institutional goals in relation to the state system, each strategy has its own logic and institutional consequences for the European Union. The mutually reinforcing and conflicting dynamics of these strategies will shape integration, since the enlargement of the European Union scheduled for the summer of 2004 will significantly shift the balance within the Union among states and groups pursuing different types of nationalism.

The primary purpose of nationalism is to sort out who should belong to which nation on which homeland (and on what basis), and what should happen to those who do not belong. This set of issues constitutes the most likely source of nationalist debate not only in postcommunist Europe, but also in other parts of the world, such as the Middle East and Asia. Each of the three key concepts of nation building (“nation,” “homeland,” and “self-government”) is continuously debated, but the desire for some kind of institutional self-government on a nationally defined homeland is fundamental to all nationalisms.10

Brubaker 1996 makes the “homeland” concept an important element in explaining nationalism, although he certainly is not the first theorist to do so. His use of the term homeland, however, is misleading in the European context. He labels the kin state as “external homeland,” which takes away from the more meaningful notion that most “national” groups pursue cultural reproduction in the communities where they live (rather than abroad, in the kin state). In other words, the state in which national minorities live contains their homeland; therefore, it is confusing to call the kin state their “homeland.” We use homeland to mean the territory on which a national group aspires to reproduce its culture.

The nationalism literature points out that this desire is also what distinguishes nations from ethnic groups. Although nations can evolve from ethnic groups, and ethnic groups also engage in cultural reproduction and in some cases do claim specific homelands, it is not necessary for ethnic groups to strive for self-governing institutions on a homeland. (Examples of such ethnic groups are immigrant groups, such as the Turks in Germany and the various “hyphenated Americans” in the United States.) Anthony D. Smith provides a particularly useful distinction:

[D]espite some overlap in that both belong to the same family of phenomena (collective cultural identities), the ethnic community usually has no political referent, and in many cases lacks a public culture and even a territorial dimension, since it is not necessary for an ethnic community to be in physical possession of its historic territory. A nation, on the [one] hand, must occupy a homeland of its own, at least for a long period of time, in order to constitute itself as a nation; and to aspire to nationhood and be recognized as a nation, it also needs to evolve a public culture and desire some degree of self-determination. On the other hand, it is not necessary…for a nation to possess a sovereign state of its own, but only to have an aspiration for a measure of autonomy coupled with the physical occupation of its homeland.11

As all nationalisms pursue institutionalized forms of national reproduction, the question is whether such pursuit must follow the traditional path—i.e., that of a nation-state. For nations that grew out of the European experience of the territorial state, national sovereignty meant being a nation-state, a congruence of political and cultural ownership of a nationally defined homeland.12

Gellner 1983. For the most comprehensive interdisciplinary overview of the literature on nationalism, see Smith 1998. See also Barrington 1997; Barkin and Cronin 1994; Hobsbawm 1992.

In Europe today, governance entails going “beyond the nation-state.”13

While in the 1990s Slobodan Milŏsević sought to ethnically cleanse his country and to alter his state's boundaries by force to include “ethnic Serb” territory held by his neighbors, other European states (including post-Milŏsević Yugoslavia) have found different ways to pursue nationalist agendas. States and groups are using these other means because they are working within the context of an increasingly EU-governed Europe—a fact that has changed political and economic calculations across the continent.Typologies of nationalism abound: ethnic versus civic, revolutionary versus counterrevolutionary, official versus protonational.14

None are exhaustive, but all provide useful clues about the ontology of nationalisms, their agents, and their consequences. Our goal is to better understand the relationship between nationalism and European integrative processes. Unlike other typologies, ours is designed specifically to elucidate the varieties of nationalism occurring within the European Union as a way of comprehending what happens to nationalism when the meaning of political-cultural congruence changes.Since in so many ways the European Union takes European populations beyond the nation-state, this typology compares national groups or governments that want to weaken state sovereignties with those that do not, and it addresses the question of what it actually means to weaken state sovereignty. Will groups become more attracted to the individualist/liberal idea and a European identity, or will they continue to reinforce particularistic cultural boundaries, or will they try to combine the two approaches?

The nationalist strategies that we delineate are traditional, substate, transsovereign, and protectionist. We define all four strategies in broad terms, lay out their competing and complementary logics, and provide examples of each type. Of special note is Hungary's “virtual nationalism,” currently the most systematically pursued post-nation-state nationalism in the region; this case highlights the relationship between nationalism and integration particularly well, so we discuss it in some detail. We also explore the interplay of nationalisms in the new Europe through a discussion of the conditions that give rise to the different types of nationalism and that make a change from one type to another more likely in the framework of integration.

As discussed above, the political science literature on nationalism focuses on the political strategy that emerged in Europe to create and reproduce congruence between the political and cultural boundaries of the nation—in other words, to form a territorially sovereign, culturally homogeneous nation-state. We call the nation-state approach traditional, because it was the dominant mechanism of state development in Europe and many other parts of the world throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the aftermath of World War I, for instance, Woodrow Wilson's idea that lasting peace and stability can be based on national self-determination carried the day and led to the creation of many of the states now in line for EU membership. And after World War II, anticolonialism in Asia and Africa unfolded in the name of national independence movements.

Rich in descriptions of traditional nationalism, the literature points to differences in particular political traditions, especially in the way “nation” has been defined in relation to the state.15

One of the most frequently drawn distinctions is that between so-called political and cultural—or, in the framework of democratization, civic and ethnic—definitions of nation. According to this dichotomy, some nations are defined on the basis of political community (citizenship) and others on the basis of common ethnicity.16Brubaker 1992.

As many scholars have pointed out, however, the practice of nationalism is more complex than this dichotomy suggests.18

Depending on particular conditions under which they act (what their territorial interests are, how far along they are in creating or consolidating a link between territory and people, and what the international framework allows or encourages at the time), nationalist political elites and publics have at times emphasized political requirements and at other times cultural requirements of nationhood. Yet all nations are ultimately both political and cultural. For instance, historians and political scientists alike have described eighteenth-century France (for many, the embodiment of civic nationalism) as a state that pursued aggressive, even violent, cultural policies aimed at turning “peasants into Frenchmen.”19Historically, aggressive cultural policies that defined nation on the basis of ethnicity accompanied traditional nation-state development. With the expansion of democracy in the Western world since World War II, however, an increased emphasis on both international stability and the accommodation of minority rights rendered all forms of aggressive traditional nation building (including violent border changes, population expulsions, and forced assimilation) unacceptable to the international community. No matter how it defines “nation,” it appears that traditional nationalism today can be reconciled with “European values” only to the extent that it is willing to tolerate national diversity within its political borders.

Most Western European states—including France and Germany, founding members of the European community—continue to uphold the “national” principle and maintain institutions that perpetuate the nation on a desired territory. At the same time, since Germany's reunification, establishing or consolidating nation-states through the traditional nationalist strategies described above has not been a primary concern for any of the current EU member states. In contemporary Europe, most governments that pursue traditional nationalism are in new states or relatively older states that have undergone dramatic institutional changes since the collapse of communism, which created new opportunities for majority-minority national contestations about the state. There also remain substate groups in Europe that maintain the traditional nationalist project of secession because they view the state in which they live as dominated by an alien group. Prominent secessionists include Catholics in Northern Ireland and Basques in Spain.

States in which traditional nationalism remains a dominant political strategy include the newly independent states of Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Serbia, and Slovakia. Older states that continue to practice nation-state policies are Bulgaria and Romania. In all of these cases (except Lithuania), political elites have seen significant challenges to their completion of a traditional nation-state project stemming from the existence of strong minorities whose kin constitute the majority in a neighboring state. In each, majority political elites have based their nation-building strategies primarily on cultural definitions of nation and continue to pursue policies of cultural assimilation.

There are, however, important differences in the choices that nationalist elites in these countries have made since the fall of communism. On the one hand, each of the three federalist structures (the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia) fell apart along nationalist lines, and the breakup of Yugoslavia unfolded through a series of violent conflicts over new boundaries. On the other hand, most state-building processes in the region have been peaceful and have favored European integration.

A number of convincing explanations have come out in recent years regarding why the disintegration of Yugoslavia was more violent than the secession of the Baltic states from the Soviet Union and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia.20

The principles of nationalism and territoriality played a fundamental role in all of these cases, yet there were fundamental differences in the way these principles shaped each process. In contrast to the former Yugoslav republics, in Czechoslovakia and the three Baltic cases, separating national groups did not compete for mutually claimed homelands. (The Russian minorities, although a sizable presence in the Baltic states, behaved rather like immigrant groups. Similarly, the Czechs and the Slovaks each did not formulate a homeland claim for the other's part of the former federation.) The choices that dominant political elites made as conflicts over nation building unfolded were equally critical factors in the peaceful or violent nature of secession. Most notably, despite fears to the contrary, the leadership of post-Soviet Russia opted against violent repression in the Baltics. Even under Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev, the use of force in the Baltics to stem secessionism, while tragic, was quite limited; the Serbian leadership, by contrast, chose violence in its effort to preserve a “Greater Serbia.”The significance of elite choices remained just as prominent after the initial phase of state formation. Where traditional nationalism was dominant, political elites were fundamental in defining majority-minority relations in either conflictual or consensual terms. Governments interested in EU membership from the beginning of the postcommunist period (such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) were also more likely to accommodate national minority demands than those putting the goal of cultural homogeneity before European integration (as did Serbia, and Slovakia under the government of Vladimir Meciar). In Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovakia, the conflictual governments in place for the better part of the postcommunist decade were replaced by the end of the decade by consensual governments that cooperated with minority parties and emphasized EU and NATO membership. In cases like Estonia, Romania, and Macedonia, treatment of minorities over language or citizenship law has also been more pluralist than it likely would have been in the absence of potential EU and NATO membership.21

Post-Meciar Slovakia and even post-Milŏsević Serbia have responded to the incentives of joining the West in a similar fashion, although remnants of a more virulent nationalism remain in both places.What binds these cases together is that the countries all continue to pursue political-cultural congruence within a nation-state model. In the logic of this nationalism, states or groups are most likely to view the European Union as an alliance among state governments, in which state sovereignty is emphasized, rather than the pursuit of a truly integrated culture. But as EU/NATO enlargement advocates have hoped, traditional projects pursued by states in the East have for the most part been rather moderate, as aspirant countries try to fulfill the demands of the European Union's acquis communautaire22

The acquis is the body of EU laws and regulations agreed to by its members. It now numbers more than 80,000 pages.

For a good comparison of Belarus to nationalist, pro-Western Lithuania, see Abdelal 2001.

Substate nationalism pertains to groups that view themselves as rightful owners of a homeland but that have no state to call their own. Within the European Union, communities that can claim historical connections to the land (in some instances, even past statehood) are considered “historical national minorities” and are differentiated from relatively recent migrant or immigrant groups.24

Tabouret-Keller 1999.

“Homeland community” is a useful concept for understanding such communities in Europe. These communities consider the place where they have a lengthy history to be their homeland; they usually have a historiography, geography, and literature that tell the story of the link between the community and the territory; and they seek some form of self-government in that homeland. Many times, the same territory is considered a homeland by more than one community.25

See the distinction between “homeland societies and immigrant diasporas” in Esman 1994, 6–7.

Substate nationalists do not seek independent statehood and thereby differ from secessionist movements that fall in the traditional nationalist category. Instead, they aspire to maintain political representation and institutions that guarantee the continued reproduction of the community.

Within Western Europe, substate nationalists in Bavaria, Catalonia, North Rhine-Westphalia, Salzburg, Scotland, Wallonia, and Flanders have asserted themselves as regional actors and pursued a transnational cooperative strategy to achieve greater representation and opportunity within the EU structures. This cooperation among substate groups became increasingly urgent as the European Union embarked on its Constitutional Convention process. Each region, as one representative has claimed, has in common a “package of powers granted to it by its country's constitution, a government and parliament of its own and [the ability to] promulgate laws autonomously and often even at the same level as the sovereign states.”26

Colloquium of the Constitutional Regions 2001.

Rather than seek independence as a traditional nationalist project would, these regions aim to use the European Union to achieve greater self-government. Jordi Pujol, Catalonia's leader for 23 years, articulated the essence of such a strategy: “Catalonia has two priorities: to assert…its personality as a national, linguistic, cultural, and economic entity, and also to contribute to Spain's progress as a whole.” He added: “It's a clear example here [that] we have constructive, positive nationalism. We've always been very pro-Europe, even 30 years ago when Spain was against it.”28

Championing the Catalan nation 1999.

Dewael 2001. In 1988, Catalonia, Lombardy, Baden-Württemberg, and Rhône-Alpes formed an association to coordinate economic policy. See Anderson and Goodman 1995.

On this demand, see, e.g., Generalitat de Catalunya 2003.

It is the Union as a supranational institution that has enabled regions to pursue this transnational cooperation over the past decade. As Devashree Gupta argues, “By encouraging the creation of transnational networks, the EU acts as an ally; by providing the political space for these networks to form, the EU acts as a facilitator; and by virtue of its policy competency in areas of particular concern to nationalist actors, it acts as a target for mobilization.”31

Gupta 2002, 17.

Substate nationalist actors hope that the European Union will weaken the authority of the central state government and allow the regions greater pursuit of their nationalist agendas. Thus, this type of nationalism is similar in emphasis to transsovereign nationalism (discussed below) in that it envisions the Union as an alliance of nations rather than one of states.

Not all regions will necessarily remain content with this approach, however, so substate nationalism could turn into a traditional secessionist project. The European Union may also play an important role here. The Scottish National Party (SNP), for example, has over time come to see the Union as a vehicle that can help make statehood a viable option rather than as an obstacle to independence. Because the Union has a common market, independence within its space would allow continued access to the English market, the loss of which was viewed in the 1970s as a significant potential cost of independence. Furthermore, the SNP believes that being an EU member state would provide more political clout for Scotland. In fact, for Labour and SNP voters, argues one scholar, “in the 1990s, demand for self-government became positively associated with support for the EU, a complete reversal of the 1979 situation when support for self-government was negatively correlated with support for the EU.”32

Dardanelli 2002, 19.

Scholars looking at the factors that might drive such sweeping change have suggested that institutional structures, such as the electoral system, may be relevant. In their study of European politics, John Ishiyama and Marijke Breuning assert that a proportional representation system, for instance, has a radicalizing influence on nationalist agendas since it allows for greater opportunity to get elected to parliament, whereas a first-past-the-post system has a moderating influence. The type of electoral system, they argue, “determines the likelihood that an ethnopolitical party gains representation” and “whether the party remains broad-based and moderate or fragments and radicalizes.”34

Ishiyama and Breuning 1998, 166.

Transsovereign nationalism applies to nations that reach beyond current state boundaries but forgo the idea of border changes, primarily because it is too costly to pursue border changes in contemporary Europe. After World War II, stability in Europe was of paramount importance; therefore, the international system delegitimized the creation of new nation-states on the continent and instead encouraged national homogenization policies within already existing state boundaries. European state boundaries were then codified by the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, which legitimated only peaceful border changes.

After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of communist federations, the international community again approved the creation of new states along the national lines that had been previously maintained and reproduced within those communist federations. Thus, for example, Georgia and Bosnia-Herzegovina were granted recognition by the international community, but entities within the republics of the former Soviet Union and the former Yugoslavia, such as Chechnya and Kosovo, were not. The violent conflicts in Russia over Chechnya and in the Balkans throughout the 1990s have demonstrated that the cost of a traditional nationalism, which requires either secession or a change in state boundaries, remains extraordinarily high in Europe. Thus, transsovereign nationalism shares the traditional emphasis that political organization should occur along national lines; but instead of forming a nation-state either through territorial changes or the repatriation of conationals within its political borders, the national center creates institutions that maintain and reproduce the nation across existing state borders.35

Again, Brubaker's (1996) notion of nation as an institutionalized form is useful. Brubaker also takes account of a “triadic nexus,” or “interdependent relational nexus,” that involves two neighboring states and a national minority that resides in one state and “belongs” culturally to the other state. He leaves the broader dynamics of European integration and its importance for nationalist strategies out of his relational model, however.

Examples of transsovereign nationalism include Austrian policies toward the German-speaking community in the Italian province of South Tirol after World War II, Russian policies toward ethnic Russians living in former Soviet republics like Latvia and Ukraine, and Romanian policies toward ethnic Romanians in Moldova. (The last case is not clear-cut: whereas Hungary formally resigned its territorial claims in bilateral treaties with its neighbors, the Romanian state has done so in relation with Ukraine but not with Moldova.) A friendship treaty that the Moldovan government is pressuring the Romanian government to sign has been delayed for a long time because the Romanians insist on including an article in the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact denouncing the Soviet Union's takeover of the territory of Moldova from Romania. The Moldovan government has no interest in including such an article. From the Moldovan perspective, the scope of the treaty is precisely to consolidate the republic's separate statehood. Romanian elites in Bucharest, however, consider Romanians in Romania and Moldova to belong to one Romanian nation, and many would welcome the traditional solution of creating a greater Romania through border changes or reunification.36

BBC Monitoring Service 2001a; BBC Monitoring Service 2001c.

The Romanian-speaking population of Moldova has so far indicated limited interest in nation-building efforts by some political elites in Romania. Although the Romanian government's dominant national strategy remains the traditional nation-state plan it pursues internally (with its continued emphasis on state centralization and cultural homogenization), Romanian political elites are also developing a national policy toward Romanians across the border—primarily in Moldova, but also in Ukraine.

The Romanian case indicates that an important condition for the success of transsovereign nationalism is that the project of the nationalist center be shared by co-nationals across the border. Failure to mobilize minorities outside the border makes transsovereign nationalism difficult if not impossible.37

On the importance of mobilization for the success of nationalism, see Beissinger 1996.

The weakness of transsovereign national mobilization in Moldova is owing primarily to past failures of the Romanian center to foster a sense of common Romanian nationhood in this territory. When the modern Romanian state was first created at the end of the nineteenth century, it included part of the contemporary Moldova.38

For an excellent comprehensive study on Moldova, see King 2000.

Petrescu 2001.

The nation-building strategy of the Hungarian government after 1990 exemplifies the transsovereign approach particularly well. Its political elites have envisioned a nation connected by institutions across state borders. Close to three million ethnic Hungarians live outside Hungary's borders. In an integrated Europe, they will represent one of the largest historical minority groups. Traditional nationalism in the Hungarian case would aim to create a state for the Hungarian nation either through territorial claims (similar to efforts to incorporate all Serbs in a Serbian state) or through immigration policy (similar to the West German government's encouragement post–World War II of ethnic Germans' repatriation to Germany), coupled with assimilationist policies toward minority groups in Hungary. Instead of such policies, however, the postcommunist Hungarian government has designed pluralist minority policies domestically and pursued a nontraditional national project for Hungarians beyond the borders.40

The logic of this nationalism is that national aspirations are best achieved if Hungary and its neighbors become members of the European Union and state borders fade away. This national project is thus related to substate nationalism, but comes from a different angle: it is coordinated/led by a national center that is at the same time the political center of a state.Since 1990, Hungarian governments have established a whole range of institutions (governmental agencies and government-sponsored foundations) that link Hungarians living in the neighboring countries to Hungary and encourage them to remain Hungarian “in their homeland”: i.e., to with-stand assimilation and remain members of the Hungarian nation where they are instead of moving to Hungary.41

Csergo and Goldgeier 2001.

Although numerous border changes took place in postcommunist Central and Eastern Europe, all new state borders were drawn along previously existing territorial lines, by the dismemberment of federal states. Bunce 1999.

The Hungarian transsovereign national strategy has three main interlocking components: (1) a network of institutions that link Hungarians beyond the borders to those in Hungary and strengthen the political and socioeconomic status of Hungarians in their communities outside Hungary; (2) support for Hungarian minority demands for various forms of local and regional institutional autonomy; (3) the pursuit of EU membership for Hungary as well as its neighbors. This national strategy reflects a coherent set of expectations. If Hungary and all of its neighbors become EU members, then the European Union will eliminate currently existing limitations of citizenship. Within a supranational, decentralized structure that allows for strong regional institutions, Hungarians will be able to live as though there are no political borders separating them.43

BBC Monitoring Service 2001b. Also Kántor 2001.

Ruggie 1986.

The language that Hungarians use to argue for institutional autonomy relies heavily on concepts largely accepted in Western Europe, such as regionalism, devolution, and subsidiarity. Hungarian government officials have lobbied at international forums such as the Council of Europe and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, on behalf of Hungarian minority parties, and have used the general European trend toward devolution and regionalism to argue for the right to local and regional self-government for Hungarian minorities.45

Csergo 1996.

Continuing tensions between Hungary and its neighbors highlight the difficulties that Hungarian political elites face in trying unilaterally to “virtualize” their borders in a region of states that are not interested in weakening their sovereignty toward Hungary. Nor can Hungarians successfully promote regionalism and local autonomy against state governments that are adamantly opposed to such processes. At the same time, most of Hungary's neighbors are keenly interested in EU membership, raising hopes among Hungarians that—in the process of accession and integration—devolution and regionalization must in the end win the day, even in states where a traditional nation-state strategy currently constitutes the governing ideology. Therefore, the Hungarian government advocates EU membership for neighboring states.

But enlargement decisions are not made in Budapest. Although in favor of continued enlargement to the East (even after 10 states join in 2004), the European Union will continue to deal with each applicant individually, and some of Hungary's neighbors have little chance of becoming members in the near future. Slovakia and Slovenia are scheduled to enter the Union together with Hungary in 2004, but Romania will not join until at least 2007—and Croatia, Ukraine, and Serbia will not join until considerably later, if at all.46

On the problems of selective admission, see Batt and Wolczuk 2001.

Article 6(3) of the Hungarian constitution declares commitment on the part of the government to care for Hungarians abroad. A Magyar Köztársaság Alkotmánya 1998. This commitment was repeatedly expressed by consecutive Hungarian governments. Sometimes these expressions triggered heated controversy in the region.

Anticipating this situation, the Hungarian government has been looking for ways to take Hungarians from neighboring countries “virtually” into the European Union, even if the state in which they live remains outside the Union. But the idea of providing dual citizenship (similar to the policies of some of Hungary's neighboring governments, such as Romania and Croatia, toward their transborder kin) enjoys little support among political parties in Hungary.48

On the issue of dual citizenship in the European Union, see Howard 2002.

See Office of Hungarians Abroad 2003 for the law, related documents, and other literature. For a good discussion of the postmodern aspects of the law, see Fowler 2002.

I am convinced that the [Status Law] contains a number of novelties judging even by European standards and it also outlines a Hungarian concept about the Europe of the future. During the time of de Gaulle, the French thought that the European Union has to be a union of states belonging to Europe. During the time of Chancellor Kohl the Germans came to the conclusion that the Union has to be the Europe of regions. And now, we Hungarians have come up with the idea that the Europe of the future should be a Europe of communities, the Europe of national communities, and this is what the [Status Law] is all about.50

BBC Monitoring Service 2001b.

The vision of a Europe of national communities is not a Hungarian invention. Romanian Prime Minister Adrian Năastase expressed a similar objective when he declared that “the European Union will be a union of nations and not a union of anti-national integration.”51

Pârâianu 2001, 105.

On nationalism and cultural reproduction, see Schöpflin 2000.

Yet continuing controversy over the Hungarian Status Law foretells the challenges of European integration against the backdrop of divergent and competing national aspirations. The law triggered political debate in Hungary and vehement opposition from Hungary's two neighbors with large Hungarian minority populations. The Romanian and Slovak governments expressed serious concerns that the legislation weakens their exclusive sovereignty over ethnic Hungarian citizens and discriminates against majority nationals in neighboring countries. Not surprisingly, debate over the Status Law brought Hungary's relations with its neighbors (especially with Romania and Slovakia) to a dangerously low point.53

Office of Hungarians Abroad 2001b; Reuters 2002; BBC Monitoring Service 2002. For a comprehensive discussion of the law, see Kántor 2002.

Responding to these tensions, the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) issued a report on the Status Law, urging the Hungarian government to follow established “European standards” and coordinate its policies with those of neighboring countries where Hungarians live. Seeking to define a set of “European standards,” the Commission compared the law with similar pieces of legislation adopted by other European states (among them, Slovakia) that provide various benefits for transborder kin, and recommended a number of changes to the Status Law.54

For a discussion of the difficulties of identifying these standards, see Weber 2002.

Office of Hungarians Abroad 2001a; A kormány elôtt a státustörvény 2001; Pfaff 2002.

The regional debate over the Hungarian Status Law exemplifies the complex interplay among the types of nationalism outlined in this article. In Hungary the law is part of a coherent transsovereign national strategy, with an emphasis on national identity (rather than citizenship) as a primary basis of sociocultural organization. The law promotes common Hungarian nationhood in the Carpathian Basin (which Hungarians consider their historical homeland), with shared sociocultural and economic institutions. An alternative national strategy would limit the definition of the Hungarian nation to Hungary and consider Hungarians living outside Hungary “ethnic Hungarian groups” rather than members of a unified nation. In this sense, the Status Law constitutes a significant statement about Hungarian nation building.56

The government of Hungary is not the sole determinant of the Hungarian project. The economic attraction of the center is a significant component of transsovereign nationalism even in cases where co-national communities outside the borders do have a strong sense of common nationhood. Hungarians in Austria and Slovenia, for example, are much less interested in the Hungarian government's nation-building project than are those in Hungary's less well-off neighboring countries. (It is important to note that the Hungarian government is also not particularly interested in mobilizing the Hungarians in Austria and Slovenia.) Similarly, the degree of mobilization among Russian communities outside of Russia is influenced by their economic well-being compared with that of their conationals in the center. Russians in Moldova, for example, have been more mobilized than those in the Baltic republics, where over time the desire to stay and integrate has grown stronger because of the increasingly obvious positive economic trajectories.

The three kinds of nationalism discussed above involve establishing patterns of hierarchy among national entities that have historically shared a territory in Europe. Most, if not all, of the majority and minority (state-centered and substate) entities that pursue national strategies also seek membership in a common European institutional framework and culture. Since World War II, however, Western European states have attracted growing numbers of immigrants from other parts of the world, and this process (against the backdrop of dramatic changes in the global economic and political system) has engendered another kind of nontraditional nationalism in Europe—a protectionist nationalism that is primarily driven by fear of unpredictability in societies experiencing rapid demographic, racial, and cultural change. This kind of nationalism is characteristic of majority nationals in states that have for a significant time enjoyed effective sovereignty over their territory and have been successfully reproducing a national culture that is widely shared by their population.57

Billig 1995 uses the term “banal nationalism” for everyday nationalism in such established democratic societies.

Most often described as right-wing extremism, neofascism, or—in its less violent form—“ur-conservatism,” this political strategy aims to protect the national culture and space, as well as the specifically national reproduction process, from groups and institutions that threaten to introduce dramatic changes.58

For discussions of “ur-conservatism,” see O'Sullivan 2001; Gray 2002. Gray argues that the Enlightenment view of progress is a myth and that what people want from their government is security, prosperity, and “recognition of their particular, usually religious or ethnic identities,” which in his view are unchanging.

The attitude of right-wing Western European nationalists toward the European Union is complicated. These groups tend to be pro-market (and thus most concerned not with the Union per se but the “welfare statism” of European countries). They combine this attitude, however, with the xenophobic view that immigrants increase both economic costs (e.g., welfare) and crime, and also undermine the “traditional” national community. As Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader of the National Front in France, has expressed: “Massive immigration has only just begun. It is the biggest problem facing France, Europe and probably the world. We risk being submerged.”59

See Schofield 2002.

Herbert Kitschelt has argued that popularity of right-wing parties such as Le Pen's depends on their ability to combine market-liberal economic policies with “an authoritarian and particularistic stance on political questions of participatory democracy, of individual autonomy of lifestyles and cultural expressions, and of citizenship status.”60

Logically, a European Union that combined a common internal market with strong barriers against an influx from outside the EU space would fit well with the right-wing agenda. And many of the complaints from protectionist nationalists concern economic integration external to the Union. But the “Euro-skepticism” of these nationalists grows as the Union begins incorporating people who are culturally different from current members. Eastern European immigrants may be seen as better than immigrants from Africa or the Middle East, but they are not particularly welcome (as is indicated by the rule that will be adopted by the European Union that prevents the populations of the new members from working elsewhere in the Union for seven years.) And a breakdown of internal borders inevitably threatens the national ideal held dear by the traditionalists.61See Mudde 2000 on the Western European resentment of enlargement costs and on how even deepening is viewed as a threat because of the elimination of internal borders.

What is emerging in the larger Europe in many ways parallels the experience of the two Germanys. Westerners pursuing protectionist nationalism believe that the costs of including poor Eastern cousins are too high; Easterners pursuing traditional nationalist projects resent what they view as the imperialism of the West. As Michael Minkenberg succinctly notes for both Germany and Europe: “In the West, radical right-wing voters have resentments against the Easterners; in the East, it is the other way round.”62

The question is not whether nation building will continue in an integrated Europe, but how the new European framework will provide room for different, in some cases conflicting, kinds of national aspirations. Will the European Union's enlargement to the East bring new sources of nationalist conflict and create dynamics in which the traditional nationalism of the newcomers will counter the newer forms of nationalism prevalent in already integrated members? In other words, has Hans Kohn's classic distinction between the more advanced (civic, rational, and universal) nationalism of “the West” and the more backward (cultural, mystic, and particularistic) nationalism of “the East” gained renewed relevance?63

On Kohn's influence, see Dieckhoff 1996.

Although all four of the national strategies discussed in this article exist across the continent, and they usually coexist in some constellation within individual European societies, it is possible to identify dominant patterns and trends both in individual cases and in regions. One such discernable pattern is that traditional and transsovereign nationalism are currently more characteristic of postcommunist Europe, and substate and protectionist nationalism more likely in current EU members. Yet this variation should not suggest either that “Eastern” nationalisms are of an older kind or that they are more antagonistic to integrative processes than their “Western” counterparts. What we describe as traditional nationalism does not in all cases precede what we describe as nontraditional forms, such as substate or protectionist nationalism. In fact, substate nationalism existed in Austria-Hungary before the empire fell apart on the basis of the nation-state principle. Transsovereign nationalism, currently more evident in the East, is in many ways more postmodern than the nationalisms characteristic in established Western democracies, which are supposedly more advanced on the route beyond the modern nation-state model. The relationships among these nationalist strategies and transitions from one to another do not follow some kind of linear sequence of development. Rather, they evolve as a web of interlocking relationships in which different nationalisms react to, constrain, and empower one another.

Thus, some national projects will be mutually reinforcing; others will compete against one another in shaping the institutional design of the future European Union. Whereas traditional nationalists in the East seek to consolidate state sovereignty, transsovereign nationalists there want to virtualize state borders and in spirit are similar to substate nationalists in the West. Meanwhile, traditional nationalists in the East have many of the same concerns about state and cultural coherence as do protectionists in the West. Based on the logics outlined in the previous pages, likely allies are traditionalists (more prominent in the East) with protectionists (more prominent in the West), as well as substaters (more prominent in the West) with transsovereign nationalists (more prominent in the East). Likely competitors are traditionalists (more prominent in the East) versus substaters (more prominent in the West), as well as traditionalists versus transsovereign nationalists (both prevalent in the East). For a visual representation of this allies/competitors breakdown, see Table 2.

As Table 2 demonstrates, it would be misleading to frame the nationalism-integration relationship in terms of an East-West dichotomy. Yet it is equally important to account for the prevalence of traditional nationalism and sources of nationalist conflicts in the countries about to become part of the European Union. We conclude by delineating the factors that help explain the variation of nationalist strategies across the continent and the ways in which further EU development will shape and be shaped by these nationalisms.

Beyond such obvious factors as variation in ethnic composition (the size and organization of groups), national institutional strategy depends on whether a group defines itself as a “homeland community” and as either a separate nation or part of another nation, and whether groups compete with one another over the same homeland territory. The Serb-Croat, Serb-Albanian, and other conflicts in the Balkans exemplify aggressive traditional nationalism, in which groups compete for mutually claimed homelands. By contrast, a key reason why the Czechoslovak “divorce” evolved into a nonviolent form of traditional nationalism was that the Czechs and the Slovaks had no homeland quarrels. When the Baltic states claimed independence, the Russian minorities did not formulate homeland claims. At the same time, the significant percentage of Latvia and Estonia's total population consisting of these Russian minorities, their previous status as the dominant ethnic group in the Soviet Union, and the proximity of neighboring kin in Russia enables Russians in the Baltic region to develop either substate or transsovereign national strategies—neither of which strive to redraw state borders.

The examples of Slovakia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic highlight both the continued significance of initial conditions in national strategy and the kinds of changes that the EU framework may facilitate. Of these successor states of the former Habsburg Empire, each currently considered a likely success story of European integration, postcommunist Slovakia represents traditional nationalism, Hungary transsovereign nationalism, and the Czech Republic protectionist nationalism. None of these cases is a pure example of a single nationalist strategy; nevertheless, it is useful to identify in each one a dominant type of nationalism and the formative influence of integration.

Slovaks were a substate nation without a sovereign state until 1993. The state they established in that year includes a large Hungarian minority that claims to belong to a different nation and participates in a different national project. The first government of independent Slovakia chose aggressive policies to stifle Hungarian minority national aspirations. Since the 1998 change of government, however, Slovak policies have been moderate and accommodationist, largely as a result of the country's desires for EU and NATO membership. Contrary to the Slovaks, the Hungarians had a state of their own (although one with limited sovereignty) at the time of the communist collapse. This initial condition and the prospects for an EU framework together contribute to contemporary Hungarian transsovereign nationalism. Similar to the Slovaks, the Czechs ended up with a newly independent nation-state after the collapse of Czechoslovakia. But they enjoy a very different position from that of the Slovaks and the Hungarians; the Czechs have no substate national groups inside (Moravia is hardly considered a separate nation) and no Czechs outside their borders to worry about. Consequently, they are not concerned with the same “national” issues of defining who belongs to the nation and what to do with those who do not belong. They have, though, demonstrated an increasing degree of protectionist nationalism in their treatment of the Roma and also in their Euro-skepticism. (Ironically, in the Czech case, the reality of European integration has made nationalism more salient than separation from the Slovaks.)

The institutional strategies that nationalist elites and publics choose are also shaped by institutional legacies and the evolving European framework. In a neighborhood of multinational states (i.e., states that have multiple groups making “national” claims), a primary question is whether cultural reproduction should be delinked from the unitary state that has served as the dominant model for the modern nation-state. Does greater regional (“homeland”) autonomy encourage national minority groups to stay within the state structure and formulate substate institutional claims rather than secessionist goals? Numerous Western cases in the post–World War II period (such as the Aland Islands, South Tirol, Catalonia, Flanders, Wales, and Scotland) suggest that devolution of power allows for substate nationalism where traditional nation-state logic previously would have called for secession. Will Kymlicka describes this postwar change as a “shift from suppressing substate nationalisms to accommodating them through regional autonomy and official language rights,” and he claims that “[a]mongst the Western democracies with a sizeable national minority, only France is an exception to this trend, in its refusal to grant autonomy to its main substate nationalist group in Corsica.”64

Kymlicka 2002, 4.

Postcommunist cases have differently demonstrated the relationship between power and nationalism. Although Marxist ideology was at least initially internationalist and explicitly antinationalist, communism in practice became nationalist everywhere in Central and Eastern Europe. (Factors that predated the communist period and that partly explain this nationalism warrant closer attention than we can provide here.) Some centralized multiethnic states had federal structures and others unitary structures. Whether federal or unitary, however, the centralized communist state provided ideal conditions for traditional nationalism. The absence of private property and of individual rights allowed the state unchecked freedom to modernize through colonization and population movement: i.e., to design urban development and industrialization in ways that supported nation-state goals. This institutional legacy helps explain the prevalence of traditional nationalism in postcommunist countries. All federal structures fell apart mainly because nationalism was a dominant substate organizing principle in these states.65

In the same vein, most unitary states continued to pursue national assimilationist policies characteristic of the previous period.66One of the best accounts of nationalism during the communist period is Verdery 1991.

Although questions of political-cultural congruence appear more salient on the Eastern side of the former Iron Curtain, they remain relevant throughout Europe. There are indications that divergent institutional processes in the West after World War II—regionalism and integration—did not lead to the abandonment of nation-state ideas in all cases. At least one study asserts that some substate Western European national parties are more radical in their institutional aspirations than their Eastern counterparts, indicating that the devolution of power (especially territorial autonomy) is no institutional panacea.67

Ishiyama and Breuning 1998.

Thus, across the continent, the debate continues over what institutional forms of national reproduction best serve individual and minority rights as well as international stability.68

Although a set of norms has emerged in the European Union that favors institutions allowing for the reproduction of minority cultures, and European institutions have been promoting these norms in their accession negotiations with candidate countries, the Union has no body of law for minority protection. Ultimately, national strategies in Europe remain rooted in divergent conceptions of sovereignty and similarly divergent internal constraints, so the opportunity structures that the European Union offers will remain flexible.69About the absence of a coherent institutional model for minority policy and the benefits of flexibility, see Brusis 2003.

As integration provides new choices (constraints and opportunities) for national majorities and minorities alike, political elites in both established and new EU member countries will continue to play a key part in shaping national strategies. Traditional and protectionist national elites that emphasize state sovereignty and envision the European Union as an alliance of states are likely to continue pursuing institutions that centralize cultural reproduction (in the educational system, language legislation, and so on) but will be compelled to accommodate their minorities. Those in favor of substate and transsovereign institutional forms will continue to push for the virtualization of borders but will have to give up some of their hopes, as titular majorities are in a position of power and are unlikely to render state borders irrelevant.

EU enlargement and decisions regarding governance will have a crucial impact on how elites and publics select their national strategies. Simply because a group in the West has for the moment chosen substate nationalism or a state like Hungary has chosen transsovereign nationalism does not mean that the strategy is fixed. Nationalist elites of substate groups who do not have significant transborder kin in neigh-boring states—the Scots, for instance—can either seek institutional forms of national reproduction within existing frameworks or turn to traditional nation-state strategies (such as secession). If the European Union does not provide Western European regions with the voice they want, more traditional projects may emerge. But those with transborder kin have other options. For instance, the ethnic Russians in Estonia and Latvia may choose between different substate forms of Russian minority nationalism in these states, or they may select transsovereign nationalism in an institutional network coordinated by Moscow. Among Hungarian minorities in Hungary's neighboring states, currently engaged both in substate nationalism and in Hungary's integrated transsovereign national project, substate nationalism may become more prevalent in the future. We discussed earlier that there is little evidence at this time that traditional nationalism may become dominant in Hungary. If, however, protectionist nationalism leads to a type of common immigration policy for the European Union that throws up strong barriers between Hungary and its neighbors, those satisfied with the transsovereign approach today may sound the call for a more traditional project tomorrow. Romanians in Moldova may continue to pursue a separate state, unite with Romania, or develop a robust transsovereign national project that coordinates a common national culture without border changes. Protectionist nationalism may also become more prominent across the continent, as Eastern European countries grow economically stronger and more attractive to immigrants, and the Roma population currently concentrated in the East takes advantage of the opportunities for mobility in a larger Europe.

The European Union not only “pools and shares sovereignty” (in words all too familiar to longtime EU watchers), but especially after enlargement to the East, it will pool and share different varieties of nationalism. Scholars have argued that nationalists in Europe are by definition anti-integration. As we have discussed, however, some nationalist projects fit well within the European Union's endeavor—and in fact, some national groups see the Union as a vehicle for achieving long-sought goals through nontraditional and nonviolent means. Even in the case of more traditional state-building projects in the East, the prospect of European Union membership has led to accommodationist approaches with respect to minority populations. Rather than eliminating nationalism, the European Union provides a framework for nation-building strategies that are less likely to threaten democratic stability in Europe than are the more extreme forms of traditional nationalism.

We have also argued that territoriality does not appear to be losing its significance when nationalism meets integrative processes. Indeed, “homeland” territoriality remains a fundamental organizing principle of modern Europe, but the agents of nationalism and their institutional interests and aspirations are becoming more diverse—creating a complex interplay of nationalist strategies with new points of friction but also new opportunities for cooperation. We have described a constellation of four types of nationalism, rooted in different initial conditions and pursuing divergent (at times conflicting, at times mutually reinforcing) ideas of sovereignty. Their impact on the European Union's long-term institutional design will emerge from the dynamics of the relationships among them. Traditional and protectionist projects continue to emphasize state sovereignty and are therefore more likely to push for a different internal design for the Union than are substate and transsovereign strategies, both of which de-emphasize state sovereignty. Traditional projects that seek to consolidate nation-state congruence will continue to view both substate nationalism and transsovereign nationalism as a challenge. Societies where protectionist nationalism gains prominence (such as France, Austria, and, in recent years, Belgium) will also be reluctant to concede the idea of cultural coherence that the nation-state model has upheld, especially if the European Union's enlargement increases the pace of demographic and cultural change. But any increased emphasis on internal state borders and national unity within the Union may lead to radicalization among nationalist movements that are currently content with sub-state institutional forms of national reproduction in the hopes that the larger European framework will ultimately weaken the relevance of existing national majority-minority hierarchies. Similarly, national groups that currently pursue transsovereign strategies—or might in the future—may later turn to more traditional and confrontational forms that would indeed hinder integration.

How national groups define themselves vis-à-vis states depends on initial conditions and also influences the groups' ideas about the European Union (e.g., whether it should be an alliance of states, an alliance of nations, or a more integrated pan-European structure). European integrative processes, in turn, influence national strategies. In the Slovak case, EU and NATO pressure contributed to moderation; in the Hungarian case, to the formulation of an institutional alternative to revisionism; in the Czech case, to the articulation of nationalism that, because of the relative cultural homogeneity of Czech society and lack of Roma mobilization, may otherwise not have gained salience.

If the EU process moves in the direction of an alliance of states (rather than an institutional framework that de-emphasizes state boundaries), substate nationalists may look to secessionism as a way of becoming equal members with other European nations. By challenging state governments for greater territorial sovereignty, though, substate nationalists may reinforce titular majority views that a continued emphasis on state sovereignty (the idea of the European Union as an alliance of states) is important precisely because it prevents substate groups from gaining strength and turning to secessionism. In Eastern European states in line for EU membership, nationalism seems to follow a similar logic. Although governments that do pursue EU membership are working toward more accommodative approaches, they are not giving up centralized nation-building strategies. Titular majorities in unitary states with significant national minorities are unlikely to devolve power to local levels in ways that empower sub-state minorities to claim institutional autonomy.

In all cases, the most important question is whether any changes in national strategy will involve democratic channels or, instead, some form of violence. The evidence suggests that the overwhelming majority of national groups throughout the continent favor the former route.

The European Union faces enormous challenges as it deepens and widens. Recognizing the different nationalist approaches rather than pretending that nationalism no longer matters will make enlargement more successful over the long run and may provide new models of nationalism for other parts of the globe. In that sense, Europe may lead the way to a postmodern world as it did to the world of the traditional nation-state earlier in history.

The authors thank Elizabeth Franker, Mistelle Olsen, and Angela Sheets for their research assistance, as well as Rawi Abdelal, Zoltan Barany, Mark Beissinger, Yitzhak Brudny, Patrice McMahon, Vladimir Tismaneanu, Jennifer Hochschild, and three anonymous reviewers for their comments. They are also grateful for the insights on this topic provided by participants at the 2002 Council on Foreign Relations Washington Roundtable seminar series on nationalism in Europe.

Table 2 Nationalist Pairings for Allies and Competitors