Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 December 2004

Mainstream comparative research on political institutions focuses primarily on formal rules. Yet in many contexts, informal institutions, ranging from bureaucratic and legislative norms to clientelism and patrimonialism, shape even more strongly political behavior and outcomes. Scholars who fail to consider these informal rules of the game risk missing many of the most important incentives and constraints that underlie political behavior. In this article we develop a framework for studying informal institutions and integrating them into comparative institutional analysis. The framework is based on a typology of four patterns of formal-informal institutional interaction: complementary, accommodating, competing, and substitutive. We then explore two issues largely ignored in the literature on this subject: the reasons and mechanisms behind the emergence of informal institutions, and the nature of their stability and change. Finally, we consider challenges in research on informal institutions, including issues of identification, measurement, and comparison.Gretchen Helmke's book Courts Under Constraints: Judges, Generals, and Presidents in Argentina, will be published by Cambridge University Press. Steven Levitsky is the author of Transforming Labor-Based Parties in Latin America: Argentine Peronism in Comparative Perspective and is currently writing a book on competitive authoritarian regimes in the post–Cold War era. The authors thank the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University and the Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame for generously sponsoring conferences on informal institutions. The authors also gratefully acknowledge comments from Jorge Domínguez, Anna Grzymala-Busse, Dennis Galvan, Goran Hyden, Jack Knight, Lisa Martin, Hillel Soifer, Benjamin Smith, Susan Stokes, María Victoria Murillo, and Kurt Weyland, as well as three anonymous reviewers and the editors of Perspectives on Politics.

Over the last two decades, institutional analysis has become a central focus in comparative politics. Fueled by a wave of institutional change in the developing and postcommunist worlds, scholars from diverse research traditions have studied how constitutional design, electoral systems, and other formal institutional arrangements affect political and economic outcomes.1

For an excellent survey of this literature, see Carey 2000.

Nevertheless, a growing body of research on Latin America,2

Taylor 1992; Hartlyn 1994; O'Donnell 1996; Siavelis 1997; Starn 1999; Van Cott 2000; Levitsky 2001; Levitsky 2003; Helmke 2002; Brinks 2003a; Eisenstadt 2003.

Clarke 1995; Ledeneva 1998; Böröcz 2000; Easter 2000; Sil 2001; Collins 2002a, 2003; Grzymala-Busse and Jones Luong 2002; Way 2002; Gel'man 2003.

For general analyses of informal institutions, see North 1990; Knight 1992; O'Donnell 1996; Lauth 2000.

Collins 2002b, 23, 30.

Attention to informal institutions is by no means new to political science. Earlier studies of “prismatic societies,”11

“moral economies,”12 “economies of affection,”13 legal pluralism,14 clientelism,15 corruption,16 and consociationalism,17 as well as on government-business relations in Japan,18 blat in the Soviet Union,19 and the “folkways” of the U.S. Senate20 highlighted the importance of unwritten rules. Nevertheless, informal rules have remained at the margins of the institutionalist turn in comparative politics. Indeed, much current literature assumes that actors' incentives and expectations are shaped primarily, if not exclusively, by formal rules. Such a narrow focus can be problematic, for it risks missing much of what drives political behavior and can hinder efforts to explain important political phenomena.21This article broadens the scope of comparative research on political institutions by laying the foundation for a systematic analysis of informal rules. Our motivation is simple: good institutional analysis requires rigorous attention to both formal and informal rules. Careful attention to informal institutions is critical to understanding the incentives that enable and constrain political behavior. Political actors respond to a mix of formal and informal incentives,22

and in some instances, informal incentives trump the formal ones. In postwar Italy, for example, norms of corruption were “more powerful than the laws of the state: the latter could be violated with impunity, while anyone who challenged the conventions of the illicit market would meet with certain punishment.”23 To take a different example, although Brazilian state law prohibits extra-judicial executions, informal rules and procedures within the public security apparatus enable and even encourage police officers to engage in such killing.24 Thus officers who kill suspected violent criminals know they will be protected from prosecution and possibly rewarded with a promotion or bonus.25 In such cases, a strict analysis of the formal rules would be woefully insufficient to understand the incentives driving behavior.Consideration of informal rules is also often critical to explaining institutional outcomes. Informal structures shape the performance of formal institutions in important and often unexpected ways. For example, executive-legislative relations cannot always be explained strictly in terms of constitutional design. Neopatrimonial norms permitting unregulated presidential control over state institutions in Africa and Latin America often yield a degree of executive dominance that far exceeds a presidents' constitutional authority.26

Informal institutions may also limit presidential power. In constitutional terms, Chile possesses “one of the most powerful presidencies in the world.”27Siavelis 2002a, 81.

Informal institutions also mediate the effects of electoral rules. For example, Costa Rica's proportional representation system and ban on congressional reelection offer no formal incentive for legislators to perform constituency service. Yet Costa Rican legislators routinely engage in such activities in response to informal, party-sponsored “districts” and blacklisting.30

In the area of candidate selection, studies in the United States suggest that because committed voters are more likely to participate in primaries, primary systems encourage the election of ideologically polarizing candidates.31 Yet in a context of pervasive clientelism, where primary participation is limited largely to people induced to vote by local brokers, such elections are won not by ideological candidates but by those with the largest political machine.32Informal institutions also shape formal institutional outcomes in a less visible way: by creating or strengthening incentives to comply with formal rules. In other words, they may do the enabling and constraining that is widely attributed to formal institutions.33

Since the Federalist Papers, scholars have recognized that the norms underlying formal institutions matter. The stability of the United States' presidential democracy is not only a product of the rules laid out in the Constitution, but is also rooted in informal rules (such as gracious losing, the underuse of certain formal prerogatives, and bipartisan consensus on critical issues) that prevent formal checks and balances from deteriorating into severe conflict among the branches of government.These are hardly isolated examples. Informal rules shape formal institutional outcomes in areas such as legislative politics,34

judicial politics,35 party organization,36 campaign finance,37 regime change,38 federalism,39 public administration,40 and state building.41Bringing together a large but disparate body of scholarship, we develop a research agenda aimed at incorporating informal institutions into the theoretical toolkits used by students of comparative politics.42

For other efforts in this direction, see Lauth 2000 and Pasotti and Rothstein 2002.

A few caveats are in order. Although the term informal institution encompasses a wide range of social (e.g., the handshake, or the rules of dating) and economic (e.g., black markets) institutions, we are concerned only with political rules of the game. We restrict our analysis to the modern period, when codification of law is nearly universal. Before this period, our distinction between formal and informal rules is less meaningful. Finally, although we draw on a broad range of cases, the examples we cite are illustrative only, not comprehensive.

The term informal institution has been applied to a dizzying array of phenomena, including personal networks,44

clientelism,45 corruption,46 clans and mafias,47 civil society,48 traditional culture,49 and a variety of legislative, judicial, and bureaucratic norms. We propose a more precise—and analytically useful—definition of informal institution. It should capture as much of the universe of informal rules as possible, but it must be narrow enough to distinguish informal rules from other, noninstitutional, informal phenomena.We begin with a standard definition of institutions as rules and procedures (both formal and informal) that structure social interaction by constraining and enabling actors' behavior.50

See North 1990; Knight 1992; Carey 2000.

Dia 1996; Pejovich 1999. Pejovich defines informal institutions as “traditions, customs, moral values, religious beliefs, and all other norms of behavior that have passed the test of time…. Thus, informal institutions are the part of a community's heritage that we call culture” (p. 166).

Each conceptualization fails to capture important informal institutions. For example, although some informal institutions are undoubtedly rooted in cultural traditions, many—from legislative norms to illicit patterns of party finance—have little to do with culture. With respect to the state-societal distinction, many institutions within the state (from bureaucratic norms to corruption) are also informal,54

while the rules governing many nonstate organizations (such as corporations and political parties and corporations) are widely considered to be formal. Finally, although the self-enforcing definition is analytically useful, it fails to account for the fact that informal rules may be externally enforced (for example, by clan and mafia bosses), even by the state itself (i.e., organized state corruption).55We employ a fourth approach. We define informal institutions as socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels.56

This definition borrows from Brinks 2003a and is consistent with North 1990; O'Donnell 1996; Carey 2000; and Lauth 2000. We treat informal institutions and norms synonymously. However, norms have been defined in a variety of ways, and some conceptualizations do not include external enforcement. See Elster 1989.

Ellickson 1991, 31.

Distinguishing between formal and informal institutions, however, is only half the conceptual task. “Informal institution” is often treated as a residual category, in the sense that it can be applied to virtually any behavior that departs from, or is not accounted for by, the written-down rules. To avoid this pitfall, we must say more about what an informal institution is not.

Four distinctions are worth noting. First, informal institutions should be distinguished from weak institutions. Many formal institutions are ineffective, in that rules that exist on paper are widely circumvented or ignored. Yet formal institutional weakness does not necessarily imply the presence of informal institutions. It may be that no stable or binding rules—formal or informal—exist. For example, in his seminal article on delegative democracy, Guillermo O'Donnell argued that in much of Latin America, the formal rules of representative democracy are weakly institutionalized.58

In the absence of institutionalized checks on executive power, the scope of permissible presidential behavior widened considerably, which resulted in substantial abuse of executive authority. In subsequent work, O'Donnell highlighted how particularistic informal institutions, such as clientelism, undermined the effectiveness of representative institutions.59 O'Donnell's work points to two distinct patterns of formal institutional weakness that should not be conflated. Clientelism and abuses of executive authority both depart from formal rules, but whereas the former is an informal institution, the latter is best understood as noninstitutional behavior.Second, informal institutions must be distinguished from other informal behavioral regularities. Not all patterned behavior is rule-bound or rooted in shared expectations about others' behavior.60

See Hart 1961; Knight 1992.

Third, informal institutions should be distinguished from informal organizations. Although scholars often incorporate organizations into their definition of institution,64

See Huntington 1968.

Finally, we return to the distinction between informal institutions and the broader concept of culture. Culture may help to shape informal institutions, and the frontier between the two is a critical area for research.66

In our view, however, the best way to pursue this agenda is to cast informal institutions in relatively narrow terms by defining informal institution in terms of shared expectations rather than shared values. Shared expectations may or may not be rooted in broader societal values.67For example, some indigenous institutions in Latin America draw on cultural traditions but others do not. See Yrigoyen Fajardo 2000; Van Cott 2003.

Formal and informal institutions interact in a variety of ways. In this section, we develop a typology aimed at capturing these relationships.68

Lauth 2000 distinguishes among three types of formal-informal institutional relationships: complementary, substitutive, and conflicting. He does not elaborate on these types, however.

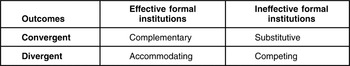

To capture these differences, our typology is based on two dimensions. The first is the degree to which formal and informal institutional outcomes converge. The distinction here is whether following informal rules produces a substantively similar or different result from that expected from a strict and exclusive adherence to formal rules. Where following the informal rule leads to a substantively different outcome, formal and informal institutions diverge. Where the two outcomes are not substantively different, formal and informal institutions converge.

The second dimension is the effectiveness of the relevant formal institutions, that is, the extent to which rules and procedures that exist on paper are enforced and complied with in practice.72

By effectiveness, we do not mean efficiency. History is littered with examples of inefficient institutions that nevertheless effectively shaped actors' expectations (North 1990).

These two dimensions produce the fourfold typology shown in figure 1. The types located in the upper left (complementary) and lower right (competing) cells correspond to the “functional” and “dysfunctional” types that predominate in much of the literature. The typology also yields two novel types (accommodating and substitutive) that allow us to make sense of other, less familiar institutional patterns.

A typology of informal institutions

The left side of the figure corresponds to informal institutions that coexist with effective formal institutions, such that actors expect that the rules that exist on paper will be enforced. The upper left corner combines effective formal rules and convergent outcomes, producing what Lauth calls complementary informal institutions.73

Such institutions “fill in gaps” either by addressing contingencies not dealt with in the formal rules or by facilitating the pursuit of individual goals within the formal institutional framework. These informal institutions often enhance efficiency. Examples include the myriad norms, routines, and operating procedures that ease decision making and coordination within bureaucracies,74 and judicial norms (such as the opinion assignment procedures and the “Rule of Four”) that facilitate the work of the U.S. Supreme Court.75Complementary informal institutions may also serve as a foundation for formal institutions, creating or strengthening incentives to comply with formal rules that might otherwise exist merely on paper.76

Thus scholars have linked the effectiveness of the U.S. Constitution to a complementary set of shared beliefs and expectations among citizens.77North, Summerhill, and Weingast, 2000.

The lower left corner of figure 1, which combines effective formal institutions and divergent outcomes, corresponds to accommodating informal institutions. These informal institutions create incentives to behave in ways that alter the substantive effects of formal rules, but without directly violating them; they contradict the spirit, but not the letter, of the formal rules. Accommodating informal institutions are often created by actors who dislike outcomes generated by the formal rules but are unable to change or openly violate those rules. As such, they often help to reconcile these actors' interests with the existing formal institutional arrangements. Hence, although accommodating informal institutions may not be efficiency enhancing, they may enhance the stability of formal institutions by dampening demands for change.

Chile's executive-legislative power-sharing mechanisms are a clear example. Leaders of the Democratic Concertation inherited an “exaggeratedly strong presidential system” and a majoritarian electoral system that ran counter to their goal of maintaining a broad multiparty coalition.80

Siavelis 2002b, 10–11.

Ibid., 21.

Dutch consociational practices may also be characterized as accommodating. The Netherlands' post-1917 democracy was based on a set of “informal, unwritten rules” of elite accommodation and power sharing, including extensive consultation in policy making, mutual veto power, and the proportional allocation of government jobs among political parties.82

Lijphart 1975, 122–38.

Ibid.

Accommodating informal rules also emerged within state socialist institutions in the Soviet Union. Because strict adherence to the formal rules governing Soviet political and economic life did not allow enterprises to fulfill state targets or permit individuals to meet basic needs, a set of informal norms—commonly known as blat—emerged in which individuals met these goals through personal networks.84

Not strictly illegal, blat enabled factory managers, workers, and bureaucrats to “find a way around formal procedures.”85Ledeneva 1998, 43, 1.

Berliner 1957; Ledeneva 1998. Guanxi, or personal relationships maintained by gift giving and reciprocal favors, played a similar role in post-Maoist China. See Yang 1994.

On the right side of figure 1 we find informal institutions that coexist with ineffective formal institutions. In such cases, formal rules and procedures are not systematically enforced, which enables actors to ignore or violate them. The cell in the lower right corner combines ineffective formal rules and divergent outcomes, producing competing informal institutions. These informal institutions structure incentives in ways that are incompatible with the formal rules: to follow one rule, actors must violate another. Particularistic informal institutions such as clientelism, patrimonialism, clan politics, and corruption are among the most familiar examples.87

O'Donnell 1996; Böröcz 2000; Lauth 2000; Collins 2002a, 2003; Lindberg 2003. According to O'Donnell (1996, 40), particularistic norms are “antagonistic to one of the main aspects of the full institutional package of polyarchy…. Individuals performing roles in political and state institutions are supposed to be guided not by particularistic motives but by universalistic orientations to some version of the public good…. Where particularism is pervasive, this notion is weaker, less widely held, and seldom enforced.”

Della Porta and Vannucci 1999, 146, 15.

Ibid., 15, 122.

Competing informal institutions are often found in postcolonial contexts in which formal institutions were imposed on indigenous rules and authority structures. In postcolonial Ghana, civil servants were officially instructed to follow the rules of the public bureaucracy, but as Robert Price found, most believed they would pay a significant social cost (such as a loss of standing in the community) if they ignored kinship group norms that obliged them to provide jobs and other favors to their families and villages.90

Similarly, scholars of legal pluralism have argued that the imposition of European legal systems created “multiple systems of legal obligation.”91Hooker 1975, 2; also Griffiths 1986; Merry 1988.

Merry 1988, 869.

Finally, the upper right corner, which combines ineffective formal institutions and compatible outcomes, corresponds to substitutive informal institutions.93

Like complementary institutions, substitutive informal institutions are employed by actors who seek outcomes compatible with formal rules and procedures. Like competing institutions, however, they exist in environments where formal rules are not routinely enforced. Hence, substitutive informal institutions achieve what formal institutions were designed, but failed, to achieve.Substitutive institutions tend to emerge where state structures are weak or lack authority. During Mexico's protracted democratic transition, formal institutions of electoral dispute resolution (such as the electoral courts) lacked credibility and were frequently bypassed. In this context, officials of the national government and the opposition National Action Party resolved postelection disputes through informal concertacesiones, or “gentleman's agreements.”94

Concertacesiones thus served as a “way station” for government and opposition elites until formal institutions of electoral dispute resolution became credible.95 In rural northern Peru, where state weakness resulted in inadequate police protection and ineffective courts during the late 1970s, citizens created informal rondas campesinas (self-defense patrols) to defend their communities and ronda assemblies (informal courts) to resolve local disputes.96 In rural China, some local officials compensate for the state's incapacity to raise revenue and provide public goods by mobilizing resources through temple and lineage associations, thereby “substituting the use of these informal institutions for … formal political institutional channels of public goods provisions.”97Tsai 2001, 16.

Taken together, these four types suggest that informal institutions cannot be classified in simple dichotomous (functional versus dysfunctional) terms. Although substitutive informal institutions such as concertacesiones and rondas campesinas subvert formal rules and procedures, they may help achieve results (resolution of postelectoral conflict, public security) that the formal rules failed to achieve. And although accommodating informal institutions such as consociationalism violate the spirit of the formal rules, they may generate outcomes (democratic stability) that are viewed as broadly beneficial. It remains an open question, however, whether accommodating and substitutive institutions can contribute to the development of more effective formal structures, or whether they “crowd out” such development (by quelling demands for formal institutional change or creating new actors, skills, and interests linked to the preservation of the informal rules).98

The following two sections lay a foundation for addressing such questions.To date, much empirical literature on informal institutions has neglected questions of why and how such institutions emerge.99

The question of informal institutional emergence has been the subject of a large literature within formal political theory. See Schotter 1981; Knight 1992; Calvert 1995.

For example, some indigenous institutions widely viewed as “traditional” are in fact recent creations that merely draw on earlier traditions. See Starn 1999; Van Cott 2000, 2003; Galvan 2004.

For a critique, see Knight 1992.

See, for example, early work on legislative norms by Weingast 1979; Shepsle and Weingast 1981; Weingast and Marshall 1988.

We focus our discussion here on informal institutions that are endogenous to formal institutional structures.103

Many informal institutions emerge endogenously from formal institutional arrangements. Actors create them in an effort to subvert, mitigate the effects of, substitute for, or enhance the efficiency of formal institutions. However, other informal institutions develop independently of formal institutional structures, in response to conditions that are unrelated to (and frequently pre-date) the formal institutional context. Formal institutions may then be built on the foundation of these informal institutions (actors may formalize pre-existing informal rules or use them as the bases for designing formal ones), or they may be created without taking pre-existing informal structures into account (as occurred with many colonial institutions).

First, actors create informal rules because formal institutions are incomplete.104

Formal rules set general parameters for behavior, but they cannot cover all contingencies. Consequently, actors operating within a particular formal institutional context, such as bureaucracies and legislatures, develop norms and procedures that expedite their work or address problems not anticipated by formal rules.105Second, informal institutions may be a “second best” strategy for actors who prefer, but cannot achieve, a formal institutional solution.106

We thank Susan Stokes for suggesting this point.

A broader statement of this motivation, elaborated by Carol Mershon, is that actors create informal institutions when they deem it less costly than creating formal institutions to their liking.108

In postwar Italy, Christian Democratic leaders who sought to keep the communist and neofascist parties out of power found it easier to develop an informal “formula” to exclude those parties from governing coalitions than to push through parliament a majoritarian electoral system aimed at strengthening large moderate parties.109Ibid.

Inventing informal institutions may also be a second-best strategy where formal institutions exist on paper but are ineffective in practice. In the case of substitutive informal institutions, for example, actors create informal structures not because they dislike the formal rules, but because the existing rules—and rule-making processes—lack credibility. Thus Mexican opposition leaders engaged in concertacesiones during the 1990s because they did not view the formal electoral courts as credible, and Peruvian villagers created rondas campesinas because the state judicial system failed to enforce the rule of law.

A third motivation for creating informal institutions is the pursuit of goals not considered publicly acceptable. Because they are relatively inconspicuous,111

Mershon 1994, 50.

Informal institutions may also be created in pursuit of goals that are not internationally acceptable. For example, the geopolitical changes produced by the end of the Cold War raised the external cost of maintaining openly (e.g., military or Leninist one party) authoritarian regimes during the 1990s, which led many autocratic elites to adopt formal democratic institutions. To maintain power in this new international context, autocrats in countries like Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Peru, Russia, Ukraine, and Zimbabwe resorted to informal mechanisms of coercion and control, ranging from use of paramilitary thugs to elaborate systems of vote buying, fraud, co-optation, espionage, and blackmail.114

Understanding why actors create informal institutions is not, however, sufficient to explain how they are established. Incompleteness does not by itself explain how the need for additional rules translates into their creation (or, for that matter, why informal, rather than formal, rules are adopted). Where informal institutions are a second-best strategy, why are actors who lack the capacity to change the formal rules nevertheless able to establish and enforce informal ones? And where actors share certain illicit goals, how are they able to establish mechanisms that effectively circumvent the formal rules? In short, to avoid the functionalist trap, it is essential to examine the mechanisms by which informal institutions are established.

The construction of informal institutions differs markedly from formal rule-making processes. Whereas formal rules are created through official channels (such as executives and legislatures) and communicated and enforced by state agencies (such as the police and courts), informal rules are created, communicated, and enforced outside of public channels, and usually outside of the public eye. The actors who create and enforce them may deny having done so. Hence, their origins are often unclear.115

See, for example, Starn's account of the disputed origins of the ronda campesinas in Peru (1999, 36–69) and Ledeneva's (1998) analysis of the origins of blat in the Soviet Union.

Precisely because of these differences, scholars should take the process of informal rule-making seriously by identifying the actors, coalitions, and interests behind the creation of informal rules. To the extent that these rules are created in a context in which power and resources are unevenly distributed, they can be expected to produce winners and losers.116

Thus, following Jack Knight,117Ibid.

Processes of informal institutional emergence vary. In some cases, the process is “top down”; informal institutions may be a product of elite design and imposition (the Mexican dedazo, Dutch consociationalism), or they may emerge out of elite-level strategic interaction (Mexico's concertacesiones). In other instances (corruption, clientelism, blat) informal rules emerge out of a decentralized process involving a much larger number of actors. In either process, we may understand mechanisms of emergence in terms of focal points,118

repeated interaction,119Sugden 1986; Schotter 1981; and Calvert 1995.

Johnson 1974; Colignon and Usui 2003. Similarly, norms of restraint and flexibility within Japan's security forces have been traced to the intense socio-political conflicts in the aftermath of World War II (Katzenstein 1996).

Analyses of the origins of informal institutions must also account for how they are communicated and learned in the absence of written down rules and public enforcement. In some cases, informal institutionalization appears to be a process of social learning through widely observed instances of trial and error. The Mexican dedazo was institutionalized through a “process of learning by example,” as PRI leaders who broke the informal rules during the 1940s and 1950s suffered political defeat and marginalization, while those who played by the rules “were rewarded with better posts.”122

Langston 2003, 14–16.

Mershon 1994, 67–68.

Social networks and political organizations may also transmit informal rules. Thus the norms of Amakudari were diffused through social networks that linked universities, state bureaucracies, and private corporations,124

and informal networks within the Peruvian and Ukrainian states communicated the rules of corruption and blackmail that sustained autocratic regimes during the 1990s.125 Political parties also carry informal rules. Parties communicated power-sharing arrangements in Chile, the Netherlands, and postwar Italy;126 party organizations enforced the system of kickbacks and bribery in Italy;127Della Porta and Vannucci 1999, 93–124.

In sum, moving beyond functionalist accounts entails identifying the relevant actors and interests behind informal institutions, specifying the process by which informal rules are created, and showing how those rules are communicated to other actors in such a manner that they evolve into sets of shared expectations.

Informal institutions are often characterized as highly resistant to change, possessing a “tenacious survival ability.”129

North 1990, 45; See also Dia 1996; O'Donnell 1996; Pejovich 1999; Collins 2002b.

Lauth 2000, 24–25.

Several sources may generate the impetus for informal institutional change. One important source is formal institutional change. The impact of formal rule changes should not, of course, be overstated; many informal institutions have proved resilient even in the face of large-scale legal or administrative reform.134

Dia 1996; O'Donnell 1996; Pejovich 1999. For example, Amakudari persisted for decades despite multiple legislative reforms aimed at its eradication (Colignon and Usui 2003, 43–49); clan politics in Central Asia survived the rise and fall of the Soviet Union (Collins 2002a, 2002b); and many Soviet-era norms survived Russia's transition from state socialism to a market economy (Clarke 1995; Sil 2001).

Two types of formal institutional change are relevant here. The first is change in formal institutional design. Particularly for informal institutions that are endogenous to formal structures, a change in the design of the formal rules may affect the costs and benefits of adhering to related informal rules, which can produce rapid informal institutional change. In the case of complementary informal institutions, for example, modifying the relevant formal rules may change the nature of the gaps that the informal institution had been designed to address, which may create incentives for actors to modify or abandon the informal rule. The 1974 Bill of Rights of Subcommittees in the House of Representatives “produced a sharp change in formal rules that overrode previous informal committee structures.”135

North 1990, 88.

Informal institutional change may also be a product of changes in formal institutional strength or effectiveness. In such cases, changes in the level of enforcement of formal rules alter the costs and benefits adhering to informal institutions that compete with or substitute for those rules. For example, compliance with competing informal institutions becomes more costly with increased enforcement of the formal rules, and at some point, these costs will induce actors to abandon the informal institution. Thus the increased judicial enforcement triggered by the Mani Pulite investigations weakened corruption networks in Italy;136

the tight controls imposed by the postrevolutionary state weakened traditional gift-giving norms in Maoist China;137 and federal enforcement of civil rights legislation weakened Jim Crow practices in the South.Increased formal institutional effectiveness may also weaken substitutive informal institutions. When the credibility of previously ineffective formal structures is enhanced, the benefits associated with the use of substitutive institutions may diminish, potentially to the point of their dispensability. For example, the increased credibility of Mexico's electoral courts over the course of the 1990s reduced the incentive of opposition leaders to work through informal concertacesiones,138

and the increased effectiveness of Peru's public security and judicial systems led to the collapse of many rondas campesinas and ronda assemblies.139Other sources of informal institutional change lie outside the formal institutional context. For scholars who view informal institutions primarily as a product of culture, informal institutional change is rooted primarily in the evolution of societal values.140

Because such shifts tend to be glacial in pace, this pattern of informal institutional change will be slow and incremental. We might understand the erosion of traditional or kinship-based patterns of authority in Europe in these terms.Informal institutions may also change as the status quo conditions that sustain them change.141

Developments in the external environment may change the distribution of power and resources within a community, weakening those actors who benefit from a particular informal institution and strengthening those who seek to change it. Thus Mexico's increasingly competitive electoral environment during the 1990s strengthened local PRI leaders and activists vis-à-vis the national leadership, which allowed them to contest and eventually dismantle the dedazo system.142 In the Netherlands, a long-term decline in class and religious identities strengthened new parties that challenged the consociational rules of the game and induced established parties to abandon them.143 The growth of middle-class electorates erodes the bases of clientelism by reducing voters' dependence on the distribution of selective material goods.144 In these cases, informal institutional change tends to be incremental, as actors gradually reorient their expectations to reflect underlying changes in their and others' bargaining power.Other analytic tools may be needed to explain some rapid informal institutional change or collapse. Tipping models offer one such tool.145

These models suggest that if a sufficiently large enough number of actors become convinced that a new and better alternative exists, and if a mechanism exists through which to coordinate actors' expectations, a shift from one set of norms to another may occur quite rapidly. Gerry Mackie argues that the move to end foot binding in China hinged on creating an alternative marriage market that allowed sons to marry daughters who had natural feet, thereby escaping conventional inferiority.146Figure 2 summarizes these sources of informal institutional change. As the figure suggests, informal institutions vary considerably with respect to both the source and the pace of change. Whereas some (complementary, accommodating) are highly susceptible to changes in formal institutional design, others (substitutive, competing) are more likely to be affected by changes in formal institutional strength. With respect to the pace of change, cultural evolution is likely to produce incremental change, but formal institutional change or coordination around an alternative equilibrium may trigger the rapid collapse of informal institutions.

Sources of informal institutional change

Bringing informal institutions into mainstream comparative institutional analysis poses a new set of research challenges. A major issue is identifying and measuring informal institutions. In formal institutional analysis, this task is relatively straightforward. Because formal institutions are usually written down and officially communicated and sanctioned, their identification and measurement often requires little knowledge of particular cases, which facilitates large-n comparison. Identifying informal institutions is more challenging. A country's constitution can tell us whether it has a presidential or parliamentary system of government, but it cannot tell us about the pervasiveness of clientelism or kinship networks.

One way of identifying informal institutions is to look for instances in which similar formal rules produce different outcomes and then attribute the difference to informal institutions.147

See, for example, North 1990.

At a minimum, efforts to identify informal institutions should answer three basic questions.148

For a more elaborate discussion of how to identify and measure informal institutions, see Brinks 2003b.

An additional problem, identified by Brinks (2003b), is that some informal rules permit, but do not require, certain behavior. Under rules of this type, actors who refrain from the permitted behavior (e.g., government officials who choose not to collect bribes) do not break the informal rule and thus will not be sanctioned. In such cases, sanctions are likely to be applied only to actors who seek to formally sanction behavior permitted by the informal rules—i.e., whistle blowers.

Identifying the shared expectations and enforcement mechanisms that sustain informal institutions is a challenging task, requiring in most cases substantial knowledge of the community within which the informal institutions are embedded. Hence there is probably no substitute for intensive fieldwork in informal institutional analysis. Indeed most studies of informal institutions take the form of either abstract theory (N=0) or inductive case studies (N=1).150

Within the case study tradition, a more microlevel approach is to construct analytic narratives that blend elements of deductive and inductive reasoning. See Bates et al. 1998.

One such method is rigorous small-n comparison. Without losing the sensitivity to context that characterizes case studies, small-n analyses can begin to identify patterns of informal institutional effects, formal-informal institutional interaction, and informal institutional change. For example, Kathleen Collins's comparative study of three Central Asian states enabled her to examine the interaction between clan networks and different formal regime types.151

Similarly, Scott Desposato's analysis of legislative behavior in five Brazilian states with varying degrees of clientelism allowed him to consider how clientelism affects the functioning of legislatures with similar formal structures.152Large-n surveys may also prove useful in research on informal institutions. Survey research may capture actors' expectations and beliefs about the “actual” rules of the game. Here it is important to distinguish between conventional surveys that capture values or attitudes toward particular institutions (e.g., the World Values Survey) and those designed to capture socially shared beliefs about constraints that individuals face. An example of the latter is Susan Stokes's analysis of informal institutions of accountability in Argentina, which uses survey data to demonstrate the existence in some parts of the country of shared citizen expectations that voters will punish politicians who behave dishonestly.153

Although expectations-based surveys may initially be limited to identifying of informal institutions, they might eventually be used to generate and test causal claims.Since James March and Johan P. Olsen declared that “a new institutionalism has appeared in political science,”154

March and Olsen 1984, 734.

Weyland 2002, 67.

We have sought to provide a framework for incorporating informal rules into mainstream institutional analysis. Far from rejecting the literature on institutions, we seek to broaden and extend it, with the goal of refining, and ultimately strengthening, its theoretical framework. We see several areas for future research. First, we must posit and test hypotheses about how informal rules shape formal institutional outcomes. For example, how do clientelism and patronage networks mediate the effects of electoral and legislative rules?156

On these questions, see Kitschelt 2000; Desposato 2003 and Taylor-Robinson 2003.

Second, we need to theorize more rigorously about the emergence of informal institutions and particularly about the mechanisms through which informal rules are created, communicated, and learned. Some seemingly age-old informal institutions are in reality relatively recent reconfigurations (or reinventions); this fact makes the issues of origins all the more compelling.157

Third, we need to better understand the sources of informal institutional stability and change. One question not addressed in this article is that of codification of informal rules. In some instances, state actors opt to legalize informal institutions that are perceived to compete with or undermine formal rules. Several Latin American governments “constitutionalized” aspects of indigenous law (granting them constitutional status) during the 1990s in an effort to enhance compliance with state law.158

Similarly, in Argentina, in an effort to regulate President Carlos Menem's use of extraconstitutional decree authority, legislators included a provision for executive decrees in the 1994 Constitution.159Ferreira Rubio and Goretti 1998, 56–57.

Comparative politics research on informal institutions is still at an incipient stage. Advances are likely on several fronts, ranging from abstract formal modeling to ethnographic studies to survey research. New insights will come from a variety of disciplines, including anthropology, economics, law, sociology, and political psychology. Hence, it is essential to promote a broad and pluralistic research agenda that encourages fertilization across disciplines, methods, and regions. Given the range of areas in which informal rules and organizations matter politically, it is essential that political scientists take the real rules of the game seriously—whether they are written into parchment or not.

A typology of informal institutions

Sources of informal institutional change