Democracy has long been theorized to be its own worst enemy. Ever since Aristotle, scholars have argued that to invest a poor majority with the right to rule is to imbue them with the power to redistribute wealth from a rich minority to themselves. Whether this relatively impoverished majority is portrayed as the desperate and manipulable rabble of Aristotle’s Politics or the rational median voters of Carles Boix’s Democracy and Redistribution, the classic and enduring supposition is that democratic politics fosters redistributive economics. By unleashing the redistributive appetites of the poor majority against men of means, democratic empowerment ironically imperils democracy itself, especially in highly unequal settings. As Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson succinctly state, “the main threat against democracy comes from its redistributive nature.” Footnote 1 Extensive downward redistribution (i.e., from rich to poor) raises the likelihood that wealthy elites will enlist the support of their conservative military allies in overturning democracy and reversing redistributive policies.

It may be a timeless trope to blame the masses for undermining democracy through their redistributive demands. But we argue that it is a trumped-up charge Footnote 2 in the postcolonial world—the only cases where democracies have been toppled since World War II. At one level, we adopt the term “postcolonial world” merely as a convenience. Even though not all countries in what was once unselfconsciously dubbed the developing world or Third World are literally former colonies (e.g., Iran, Turkey, Thailand, Ethiopia, China), the term has gradually come in social-scientific circles to replace those more antiquated formulations. Practically speaking, our goal is to assess the redistributive model in the vast population of cases where levels of economic development are low enough to make outright democratic breakdown a plausible contemporary scenario. Footnote 3 At a more substantive level, we focus on the postcolonial world because, radically heterogeneous though contemporary Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East may be, these regions tend to share a set of political and economic conditions arising from legacies of European domination and “late-developer” status. Of particular importance for the analysis and argument that follow, a vast comparative literature supports our claim that postcolonial states are especially likely to lack the infrastructural power necessary to implement government goals across national territory and over the objections of powerful socioeconomic elites. Footnote 4 This lack of infrastructural power is crucially manifested in a generalized incapacity among postcolonial states to impose significant direct taxes on their wealthiest citizens. Footnote 5

The core limitation of the redistributive model when applied to postcolonial settings lies in two questionable assumptions about state power and state-society relations. The first is that military officers are the conservative agents of wealthy elites, rather than independent principals in their own right. The second is that the state’s administrative institutions have the necessary capacity to impose redistributive taxation upon the wealthy at the median voter’s behest. As we detail later, these assumptions rarely withstand careful scrutiny in the postcolonial world. While postcolonial state administrations certainly vary widely in their capacities, they tend on average to be more administratively incapable, and postcolonial military officers tend to be more independent and assertive, than the redistributive model recognizes. If there are any features that contemporary cases of military intervention share in common—from Thailand to Egypt, from Mali to the Philippines, from Fiji to Paraguay, and from South Sudan to Pakistan—we argue that it is the lethal combination of a relatively incapable bureaucracy and a relatively autonomous military.

Our state-centered theoretical alternative holds straightforward yet serious implications for the redistributive model of democratic breakdown. To the extent that postcolonial militaries must be modeled as ideologically and operationally independent political principals, officers cannot be assumed to share interests with wealthy oligarchs, much less take marching orders from them. To the extent that postcolonial states lack administrative capacity, we cannot assume that they will pursue redistributive policies effectively, regardless of regime type. In much the same way that state-centered analyses have offered a robust and indispensable alternative approach to the class-analytical paradigm on revolutions, development, identity formation, and authoritarian durability, we bring the tested analytical tools of state-society analysis to bear on the question of democratic breakdown. Footnote 6

Our intervention is empirical as well as theoretical. We amass a diverse array of quantitative and qualitative evidence that defies the leading economic explanation for democratic breakdown, while affirming our emphasis on capable states as the political keystone of democratic survival. Cross-sectional time series data from 139 countries between 1972 and 2007 show that the taxation of income, profits, and capital gains—which effectively proxies for both wealth redistribution and state capacity—is if anything negatively correlated with military coups against democratic regimes. Footnote 7 Our quantitative analysis also shows that the democratic breakdowns that follow such coups do not seem to result in any systematic reduction of redistribution. This, we contend, is because, even when regime type changes, underlying levels of state capacity—and hence effective rates of redistributive taxation—tend to remain much the same. More fine-grained comparative-historical analysis of Southeast Asia during the Cold War provides further evidence that authoritarian takeovers have neither been inspired by successful redistributive policies nor followed by their reversal. This is despite the fact that Southeast Asia’s highly unequal societies and repressive right-wing authoritarian regimes should be among the friendliest terrain for redistributive models of democratic breakdown.

So if redistribution does not best explain democratic breakdown in contemporary times, what does? Our overarching argument is that democratic breakdown in the post-World War II era is best understood as the product of postcolonial state weakness. On the militarized side of the state apparatus, officers typically overthrow democracy for reasons of their own, not in support of particular economic classes. On the postcolonial state’s civilian side, administrative incapacity means that recurrent crises of governability will repeatedly tempt and enable military intervention to restore political stability. Footnote 8 Meanwhile, democracy’s chronic failure to “deliver the goods” in weak-state settings will give the poor majority little reason to defend democracy against its enemies. In short, the roots of democratic fragility in the contemporary world primarily grow out of the political soil of weak states Footnote 9 —not the economic soil of class conflict.

Recent events in Egypt are particularly illustrative. After Hosni Mubarak was toppled in February 2011, Egyptian politics essentially became a standoff between the country’s two most powerful organizations: the Muslim Brotherhood and the military. The Brotherhood was not a vanguard for the poor, but a resolutely middle-class organization that had flourished in large measure because of its ability to provide crucial daily public goods—medical care, education, even basic infrastructure—where Egypt’s state apparatus had failed. After Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi’s democratic election to the presidency, his government did not introduce radical new policies to redistribute wealth from rich to poor, but worked feverishly to colonize Egypt’s “deep state” with Brotherhood personnel. This prompted an utter breakdown in public services and a popular abandonment of Morsi’s seemingly incompetent government. Mass anti-Morsi protests gave the military the perfect occasion in July 2013 to reclaim national power on its own terms and for its own benefit, not as a vanguard of the rich, middle class, or any specific sector of society whatsoever, but first and foremost for itself.

As this concrete political example suggests, the implications of our arguments and findings are by no means purely academic. At the heart of the scholarly debate presented here is an enormous practical and normative question: are democracies best secured by limiting state power, or by expanding it? The logical upshot of redistributive models is that democracies risk collapse unless the state refrains from making redistributive claims upon the rich. Our own analysis suggests that democracies do not imperil themselves through downward redistribution, but through failing to invest in the state-building efforts necessary to fulfill a wide range of governance tasks. We thus illustrate the importance of strong rather than limited states as the best protection against democratic breakdown. Footnote 10 When pondering recent democratic breakdowns across the globe, we suspect that their deepest sources lie in states that are accomplishing too little rather than redistributing too much.

The Redistributive Model of Democratic Breakdown

A wide array of influential scholars has located the fragility of democracy in the redistributive threat it ostensibly poses to wealthy elites. For Aristotle, democratic constitutions rest gingerly on the immoderate impulses of the multitude and the confiscatory inclinations of elected demagogues. For democracies to endure, “the rich should be spared.” Footnote 11 For Barrington Moore as well as Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyne Huber Stephens, and John Stephens, the sternest opposition to democracy emanates from landed elites fearful that popular rule will undermine surplus extraction from their dependent labor force. Footnote 12 For a newer generation of scholars, Footnote 13 the puzzle of democratic stability is best unraveled by theorizing how economic factors such as income equality, capital mobility, and natural resource endowments mitigate the threat of democratic expropriation. These various works by no means provide a singular or monocausal account of democratic breakdown, or necessarily treat democratic breakdown as their primary outcome of interest. Yet they all give class conflict and economic redistribution pride of place in their regime analyses. To be more precise, they are all built upon the shared ceteris paribus predictions that enfranchising more poor people will increase redistribution from elites, and more redistribution from elites will increase the likelihood of democratic breakdown. Footnote 14

For our purposes, Acemoglu and Robinson’s Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (hereafter EODD) represents an especially fruitful point of theoretical departure in this re-emergent redistributive tradition. To its credit, no other work brings the redistributive model of democratic breakdown so sharply into logical relief. This theoretical clarity and ambition helps explain why EODD has attracted so much attention and so many accolades. Footnote 15 Far from being a straw man, EODD has become one of the most influential books on political regimes in decades. Yet while EODD possesses the virtues of ambition and clarity, we submit that its theoretical assumptions limit its empirical applicability to cases of democratic breakdown in the postcolonial—read contemporary—world. Since nearly all scholarship in the redistributive tradition rests on very similar theoretical foundations, our line of critique has relevance for an entire line of reasoning, not simply for a single book. Footnote 16

The formal models Acemoglu and Robinson develop to predict regime outcomes rest on a common deductive premise grounded in the Meltzer–Richard model of median voters and tax policy: Footnote 17 democracies are more redistributive than dictatorships. In almost all countries the distribution of national income is right-skewed, with the rich earning a disproportionately large share of national income. Mean income thus exceeds the median, and, according to Meltzer–Richard, the decisive median voter in a democracy will support redistributive taxes and government spending. As income inequality rises, the median voter will support more redistributive policies, at greater cost to the rich. In a non-technical nutshell, the problem of democracy and redistribution from the Meltzer–Richard perspective is that the poor outnumber the rich, while the rich out-earn the poor. This guides EODD to an elegant and straightforward argument for why democracies break down:

Because the main threat against democracy comes from its redistributive nature, the greater redistribution away from the elites the more likely they are to find it in their interest to mount a coup against it . . . . Our framework predicts that in highly unequal societies, democratic policies should be highly redistributive but then abruptly come to an end with a coup that reverts back to much less redistributive policies Footnote 18 . . . .In democracy, the elites are unhappy because of the high degree of redistribution and, in consequence, may undertake coups against the democratic regime. Footnote 19

Acemoglu and Robinson’s theory of democratic breakdown is their theory of democratic transitions in reverse. Footnote 20 The citizens mobilize to overthrow dictatorship because elites are not redistributing enough; the elites conspire to overturn democracy because the citizens are voting (or at least credibly threatening) to redistribute too much.

We are not concerned here with assessing Acemoglu and Robinson’s theory of democratic transitions, which has received considerable attention elsewhere. Footnote 21 Instead, we critically assess their attempt to convert a redistributive model of democratic transitions, basically unaltered, into a redistributive model of democratic breakdown. As Guillermo O'Donnell and Philippe Schmitter rightly warned over a quarter-century ago, “political and social processes are neither symmetric nor reversible. What brings down a democracy is not the inverse of those factors that bring down an authoritarian regime.” Footnote 22 This suggests the need for a theoretical alternative; what we offer below is a state-centered alternative.

Critiquing the Redistributive Model: Towards a State-Centered Alternative

We join a growing wave of scholarship seeking to assess the empirical validity of the redistributive model. Much of this work has been rather critical in tone and negative in its findings; most of it has focused on democratization rather than reversions to authoritarianism. Footnote 23 The most influential work in this vein has come from Ben Ansell and David Samuels, who see rising income inequality as conducive to democratization because it indicates the rise of a propertied class that will seek to place limits on autocratic (i.e., expropriating) power. Footnote 24 Much like Adam Przeworski, who sees suffrage extensions historically and strategically being “granted” by vote-hungry parties as well as “conquered” by excluded groups in society, Ansell and Samuels portray democratization as a product of intra-elite negotiations and calculations rather than a response to redistributive threats from below. Footnote 25

Similar skepticism about the redistributive model of regime transitions comes from Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufman. In their exhaustive and highly original causal-process analysis of transitions in the third-wave period from 1980–2005, they find that more than 40 percent of transitions to democracy do not conform “even very loosely” to the causal mechanisms laid out in in the redistributive model, even when they use an “extremely generous” definition of distributive conflict transitions. Furthermore, a “substantial number” of distributive conflict transitions “occurred under conditions of high inequality.” Footnote 26 This suggests that the redistributive model is failing in cases where it should be most likely to shed explanatory light.

When Haggard and Kaufman turn their attention to democratic breakdowns—our core concern here—they uncover even more grounds for skepticism. They find that “an even smaller percentage of reversions—less than a third—conformed to the elite-mass dynamics postulated in the theory.” They also find that there was “little relationship between these transitions and socioeconomic inequality.” In several cases, incumbent democratic governments were actually overthrown by “authoritarian populist leaders promising more redistribution,” and most “reversions were driven by conflicts that cut across class lines or. . . conflicts in which factions of the military staged coups against incumbent office holders.” Footnote 27 In sum, Haggard and Kaufman’s meticulous qualitative analysis strongly suggests the contemporary empirical inadequacy of the redistributive model.

Yet a predominant theory like the redistributive model needs to be countered by new theory, not just new empirics. It is here where our analysis most decisively departs from Haggard and Kaufman’s. Even as they impressively and thoroughly detail the redistributive model’s empirical shortcomings, they explicitly “do not seek to elaborate an alternative theory of democratic instability.” Footnote 28 Quite sensibly, they embrace equifinality in regime outcomes and emphasize “the agnostic nature” of their findings. Footnote 29 Although we certainly admire Haggard and Kaufman’s theoretical agnosticism, we cannot say that we share it.

Like Acemoglu and Robinson’s, our causal argument for democratic breakdown is grounded in clear and well-established theoretical priors. There is a strong alternative case to be made for explaining democratic deterioration and breakdown that hinges on the capacity of states. The state-society perspective has long offered a full-blown research paradigm to complement and at times directly counter economistic and class-based perspectives on political outcomes. Footnote 30 This state-society perspective is shared by Hillel Soifer, who offers an argument that is quite close to our own here. Soifer argues that inequality should only shape regime outcomes under conditions of considerable state capacity. Absent such capacity, neither elites nor the masses have reason to expect regime change to mean redistributive change. Using census data as his proxy for state capacity in a dataset with global coverage during the years 1945–2000, Soifer shows that, “where the state is weak, inequality has no effect on regime type.” Footnote 31

The theoretical harmonies between Soifer’s argument and our own should be evident. Yet empirically, there are important differences. Most importantly, Soifer joins both proponents and critics of the redistributive paradigm by focusing his empirical attentions on inequality rather than redistribution itself. This move is indeed universal in the current literature, despite the fact that there is good reason to doubt that redistributive pressures should exhibit a one-to-one relationship with measured levels of inequality. Footnote 32 For instance, Haggard and Kaufman portray inequality as the key causal variable that undermines democracy in this research paradigm, and “distributive conflict” as a causal mechanism through which inequality has its hypothesized effect. Yet in our view, redistribution is more properly conceived as the hypothesized causal variable that produces regime outcomes in this literature, whereas inequality is merely an antecedent proxy for redistributive pressures and policies. Hence to the extent that existing works have either found empirical support for the redistributive model Footnote 33 or impugned it34 on the basis of inequality rather than redistribution data, we would argue that they are only testing the redistributive model’s core argument indirectly. In the empirical analysis that follows, we assess both a redistributive account and our own state-society account of democratic breakdown directly with data on redistribution, not indirectly with data on inequality.

But to return to our primary theoretical task at hand: why exactly is a redistributive explanation for democratic breakdown likely to be unhelpful in the postcolonial world—in other words, in the vast majority of the world’s countries, as well as the only countries where democratic collapse has been a relevant concern during the last half-century? The key lies in two questionable assumptions. One is underestimating military autonomy; the second is overestimating bureaucratic capacity. Simply put, armies in the postcolonial world have regularly had strong motives and ample opportunity to seize power in unstable democracies with weak states.

Underestimating Military Autonomy: Colonels as Agents of Capitalists?

Our first concern relates to Acemoglu and Robinson’s treatment of the balance of power and fusion of interests between economic elites and the military. At times, EODD treats the political power and efficacy of the wealthy as so unproblematic that the military vanishes from the discussion. “When the cost of a coup is zero,” the authors argue, “the rich are always willing to undertake a coup.” Footnote 35 But of course it is the military that actually has the firepower necessary to overturn a democratic regime, or to ratify a civilian executive’s autogolpe with its unrivaled coercive might. Hence Acemoglu and Robinson stake their redistributive argument for democratic collapse on an alliance between capitalists as political principals and colonels as their reactive agents.

Given that coups are generally undertaken by the military, our approach presumes that for various reasons, the military represents the interests of the elites more than those of the citizens. We believe this is a reasonable first pass; nevertheless, in practice, the objectives of the military are not always perfectly aligned with those of a single group and may have an important impact on the survival of democracy . . . . We simply take as given the possibility that, at some cost, the elites can control the military and mount a coup against democracy. Footnote 36

Is it indeed “a reasonable first pass” to assume that wealthy elites can pay military elites to do their bidding? When applied to the postcolonial world, we find EODD’s model unrealistic in its portrayal of militaries as both the allies and agents of wealthy elites. The assumption that officers are the agents of oligarchs is especially problematic. As Charles Tilly has argued, one of the defining features of the postcolonial world as opposed to Europe is the relative militarization of political life. Footnote 37 Even as military-led regimes have become globally rare, civilian-led regimes have still widely failed to assert full and effective political and legal supremacy over the military. We thus argue that any theory of democratic breakdown in the postcolonial world should recognize that officers are political principals rather than mere agents of oligarchs.

It strikes us as more plausible to claim that colonels are the natural allies, if not the responsive agents, of capitalists. Here, Acemoglu and Robinson effectively adopt what Morris Janowitz termed the “aristocratic model” of civil-military relations: “Birth, family, connections, and common ideology insure that the military will embody the ideology of dominant groups in society.” Footnote 38 This is only one viable model, however. Civil-military relations can also resemble Janowitz’s “democratic model,” in which “being a professional soldier is incompatible with holding any other significant social or political role”; or what Janowitz dubs the “totalitarian model,” in which the military becomes subservient to a ruling party.

Which if any of these theoretical models of civil-military relations best captures empirical reality? If most or even many postcolonial countries fit Janowitz’s aristocratic model, EODD’s account would indeed constitute “a reasonable first pass.” Originally writing in the mid-1960s and updating his work in the late 1970s, here is how Janowitz came down on the issue:

In the new nations, the military establishment is recruited from the middle and lower-middle classes, drawn mainly from rural areas or hinterlands. In comparison with Western European professional armies, there is a marked absence of a history of feudal domination. As a result, the military profession does not have strong allegiance to an integrated upper class which it accepts as its political leader nor does it have a pervasive conservative outlook. Footnote 39

Janowitz was by no means alone in eschewing the aristocratic model that EODD espouses. For Samuel Huntington, “oligarchic praetorianism” was most clearly associated with nineteenth-century Latin America, whereas the postcolonial world had broadly witnessed “the shift from the oligarchical pattern of governmental coups or palace revolutions to the radical, middle-class pattern of reform coups.” Footnote 40 These works drew on a plethora of case studies of military interventionism in the immediate aftermath of decolonization.

To some degree these authors’ divergence from EODD rests on divergent case selection. The 51 “new nations” in Janowitz’s study all come from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East—the same regions Huntington saw as the epicenters of “mass” and “radical praetorianism,” and which provided the fodder for most case-studies of anti-oligarchic militaries. If any postcolonial region has experienced what Janowitz calls “a history of feudal domination,” it is Latin America. It is telling, therefore, that Acemoglu and Robinson tend to draw upon Latin American cases when discussing democratic breakdown. Footnote 41

Yet even in oligarchic and unequal Latin America, highly redistributive policies such as land reform have been systematically more likely to take place under military rule than democratic rule, Footnote 42 and have only been effectively pursued under conditions of ample state capacity. Footnote 43 Curiously, even EODD’s illustrative Latin American case—Peron’s Argentina, where a military leader rose to power with the backing of organized labor and in confrontation with bourgeois elites—pointedly shows that the relationship between militaries and particular social classes is a variable rather than a constant. Footnote 44

Acemoglu and Robinson’s frank recognition that “the objectives of the military are not always perfectly aligned with those of a single group” thus strikes us as their most “reasonable first pass” at political reality in the postcolonial world. Coup-makers must certainly construct ruling coalitions after seizing power; but there is no reason to assume that “the wealthy” will constitute a coherent class with which new authoritarian rulers can coalesce, or that coup leaders will privilege a wealthy “preexisting elite” over their own, ascendant “launching organization.” Footnote 45 Indeed, this echoes the wide scholarly consensus in the study of military politics that military actions and doctrines are by no means reducible to, or even typically in accordance with, the interests of any single civilian group. Footnote 46 This raises more fundamental concerns for a redistributive explanation for democratic breakdown than Acemoglu and Robinson appear to acknowledge, however, because it breaks the logical chain linking redistributive politics to military intervention. If anything systematically incites militaries to overthrow democracy, either acting alone or in tandem with other order-prizing elites, we argue that it is not an excess of redistribution. It is a dearth of political stability and a lack of popular commitment to defending dysfunctional democratic politics.

Postcolonial states cannot be reduced to their militaries alone, however. We now turn our analytical attentions toward the side of the postcolonial state where government performance and stability are most fatefully determined: the civilian, administrative side.

Overestimating Bureaucratic Capacity: Voting on Taxes = Collecting Taxes?

Like many recent works on the political economy of regimes and redistribution, EODD adopts the Meltzer–Richard framework as a lens on redistribution in democratic settings. This familiar model posits that the median voter enjoys the privilege of setting the tax rate in democracies: “because we are in a democracy, the median voter sets a tax rate,” Acemoglu and Robinson argue. “If there is no threat of a coup from the elites, the citizens set their most preferred tax rate.” Footnote 47 Since democracies typically have more poor people than rich people—especially in the postcolonial world—the tax system in democracies should extract from the relatively rich and redistribute to the relatively poor.

Our fundamental concern with this model is that the median voter is merely a voter—she is not an omnipotent tax collector. Footnote 48 This may not be an issue in rich democracies where the state is administratively effective, compliance with taxation is relatively unproblematic, and—of more interest to us here—authoritarian takeovers have become basically unthinkable. Yet in the parts of the world where democracy remains at risk, it is rarely true that Leviathan possesses the administrative capacity to extract substantial revenues from the wealthiest members of society. Devotees of the Meltzer–Richard framework seem to disregard this common finding, yielding the puzzling implication that the same bourgeoisie that is powerful enough to tame and direct the military can only lie politically prostrate before the might of the median democratic voter.

Taxes on the rich rather than spending on the poor are of the essence in measuring redistribution; not only because the Meltzer–Richard framework explicitly bases its predictions on taxation rather than spending, but because postcolonial states often rely heavily on “unearned income” from oil, aid, and other external sources for their spending needs. Footnote 49 Acemoglu and Robinson argue that wealthy elites’ dissatisfaction portends democracy’s demise. We thus need a measure of redistribution capturing how many pounds of flesh the state extracts from the moneyed—not how many pounds of butter it doles out to the masses. Following both Kevin Morrison and Jeffrey Timmons, we consider the direct taxation of income, profits, and capital gains to be the best available indicator for taxation of elites, and hence for redistribution in postcolonial settings. Footnote 50 This measure will be of particular interest in the empirical sections to follow.

The great virtue of this indicator is its double-edged quality. On the one hand, direct taxation is the best available proxy for redistribution from elites—the key causal variable in the redistributive model. On the other hand, it is also an excellent proxy for state capacity—our own key causal variable. Footnote 51 A positive relationship between redistributive taxation and anti-democratic coups would support the redistributive model, suggesting that democracies endure as Aristotle initially claimed, by sparing the rich. Yet if high levels of redistributive taxation are associated with democratic survival, it should both impugn the redistributive model of democratic breakdown while supporting our own emphasis on state capacity as the political foundation for democratic resiliency.

Before turning our attentions to our empirics, a brief summary of our positive theoretical argument is in order. Since postcolonial states have tended to elevate the military to a forward and central role in political life, militaries have been ideally positioned and highly empowered to topple democracies when it suits their own interests, regardless of bourgeois interests. Since postcolonial states typically lack administrative capacity, recurrent crises of governability give military officers a ready rationale for toppling democratic governments rendered unpopular by their failure to materially benefit their citizenries. Since such coups do not necessarily alter underlying levels of state capacity, they should have little systematic impact on subsequent redistribution. Since robust tax collection from the rich requires substantial state capacity, it is an indicator that democracy rests upon the solid roots of a well-functioning state apparatus, not that it is stricken with destabilizing redistributive conflict. In direct contrast to the redistributive model, we expect high levels of effective redistributive taxation to stabilize democracy, and we do not expect coups against democracy to be either motivated by successful redistribution or followed by redistributive reversals. What follows lends preliminary empirical support to these theoretical claims.

Redistributive Taxation and Regime Breakdown, 1972–2007

We use time-series cross-section data from 139 countries between 1972 and 2007 to test hypotheses derived from redistributive theories as well as from our own framework centered on state capacity. After detailing our key variables and data sources, our first empirical section tests whether political regimes are generally more vulnerable to military intervention when they extract from the rich, and whether democracies in particular suffer this fate when they tax the rich heavily. We make this distinction because dictatorships might be more redistributive than scholars such as Acemoglu and Robinson suspect, and such “left-wing dictatorships” Footnote 52 might be as vulnerable to military coups as democracies—thus confirming their intuition on how redistribution threatens regimes if not on how regime types redistribute. The next section asks whether military coups tend to be followed by a reduction in redistribution. While the redistributive model would answer these questions in the affirmative, our state-centered approach suggests that the answers should be in the negative.

Data, Methods and Models

To understand the potential coup-catalyzing effects of redistribution, we estimate the impact of taxes on personal income, capital gains, and profits—which are disproportionately extracted from the better-off in society—on the likelihood of coups and coup attempts. The greatest appeal of this measure is that it conceptually captures both elite redistribution (EODD’s key variable) and state capacity (ours). For measures of coup activity, we estimate models of the general functional form:

Where X i,t-1 represents a vector of control variables.

We then explore whether, after democratic breakdowns, authoritarian regimes shift tax burdens in a rich-friendly direction. In short, does extraction from the rich lead to democratic breakdown? And, subsequently, do successful coups result in less extraction from the rich:

Although our statistical evidence is only a first cut, consistent with our framework and contradicting the redistributive model, the answer to both of these questions proves to be no.

Independent and Dependent Variables

Coups. In our first set of models, taxation is the independent variable and coups the dependent variable. We measure coup activity using data from the Polity IV project. Footnote 53 We begin by examining the subset of coups that also result in regime change. A significant share of successful coups in authoritarian regimes transfer power from one military leader to another, so we use Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz’s data on autocratic breakdown and regime transitions to exclude coups that fail to produce regime change. Footnote 54 Geddes, Wright, and Frantz define a regime as “a set of formal and/or informal rules for choosing leaders and policies.” This measure of coup activity is discrete and takes a value of 1 in any given country year in which a regime-changing coup takes place and 0 otherwise.

We then examine count data on coup activity measured by the number of successful coups, coup attempts, and the sum of rumored and confirmed plots. This alternate set of measures allows us to explore the determinants of efforts by officers to overthrow democracies, which might plausibly be numerous, that are motivated by the same factors that catalyze regime-changing coups. Including these lower-level measures of coup activity allows us to capture the full spectrum of such activity in postcolonial states. It also allows us to assess the extent to which the factors that may provoke coups, plots, or attempts differ from the ones that actually produce regime change. Many, perhaps most, postcolonial armies have disgruntled officers; but fewer would succeed in staging a coup given unpermissive structural conditions.

We first estimate the models using the complete dataset, asking whether taxing the rich threatens all political regimes. We then estimate the models using only democratic regimes. We do so by excluding years in which a country is labeled an authoritarian regime according to Jose Cheibub, Jennifer Gandhi, and James Vreeland's classification. Footnote 55 We employ coups, rather than broader indicators of regime breakdown, in order to remain maximally faithful to the political logic of the redistributive model as presented in EODD. Their model suggests a very clear dynamic of democratic breakdown—that the elite co-opt and deploy the military to redress excessive taxation. As such, we seek to give maximal leeway by using a measure conceptually closest to this dynamic.

Where coups are the independent variable predicting subsequent rates of taxation, we include a five-year lagged measure. This is because, in the first years following a coup, instability might mask a regime’s redistributive intent. Five years on, the redistribution-suppressing intent of a military regime acting on behalf of the upper class ought to be clearer.

Redistribution

To measure redistributive taxation, we use taxes on income, profits, and capital gains as a percentage of GDP, which governments disproportionately extract from the better off. These data are drawn from Michael Albertus and Victor Menaldo, who create a consistent time series of direct taxation with the greatest longitudinal coverage possible from 1972 for each country. Footnote 56 Albertus and Menaldo use several sources including International Monetary Fund (IMF) Government Finance Statistics Yearbooks, Global Development Network Growth Database Government Finance Series, The World Bank Development Indicators, Footnote 57 The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Country Reports, and IMF Country Reports. They follow the guidelines and coding rules set out in the IMF's Government Finance Statistics Yearbook. Footnote 58

This measure is optimal for assessing both redistributive and state-centered accounts of democratic breakdown. Unlike total tax revenues as a share of GDP, income and capital gains taxes focus squarely on redistribution away from the relatively wealthy. Countries across the world have marginal tax rates that rise with income, and many have deductions and other advantageous policies that benefit the poor and middle classes. Footnote 59 Moreover, in many less-developed economies only the relatively rich pay taxes, because many individuals are either too poor to pay income taxes or are not enough of a lucrative and feasible target to be worth the administrative and political trouble of taxing directly. Footnote 60 Similarly, wealthy individuals are more likely to own capital assets and shares in companies, meaning that they pay the lion's share of taxes on interest, capital gains, and corporate profits. Footnote 61 Income taxes are also the most fiscally buoyant and administratively challenging taxes to collect, Footnote 62 making them an excellent proxy for state capacity. In the first models these taxes are the independent variable, explaining coups; in the second set they are the dependent variable, explained by coups.

Control variables. We include a number of standard economic control variables in estimating both the coup and taxation models. Footnote 63 The models control for annual GDP growth because economic growth may reduce public support for coups while also increasing the government's tax take. We control for the natural logarithm of GDP per capita because the vast majority of coups occur in less developed countries, while the collection of direct taxes increases with income (driven both by increasing state capacity and demand for public spending). GDP per capita is also frequently used as a proxy for state capacity in the literature, Footnote 64 so we take the negative correlation between coup propensity and income per capita in our analysis to be additional evidence for our core argument.

To control for the hypothesis that the poor are simply “getting what they paid for” Footnote 65 in taxes, we also include a control for government expenditures as a share of GDP. Footnote 66 Resource rents, a broader manufacturing base, and greater trade openness may reduce the necessity of collecting direct taxes while also altering coup propensity in various ways. Accordingly, we include controls for resource rents, exports and imports, and manufacturing as shares of GDP. We include the natural logarithm of population to control for economies of scale in tax collection. Footnote 67

To control for cross-sectional correlation and policy diffusion, we use a similar approach to Kristian Gleditsch and Michael Ward by including a control for the percentage of democracies in each country's geographic and cultural region. Footnote 68 Democracy-years are defined by Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland's classification, Footnote 69 and regions were drawn from Stephen Haber and Victor Menaldo's data, Footnote 70 which in turn is based on work by Axel Hadenius and Jan Teorell. Footnote 71 We control for the number of years since the last coup event Footnote 72 and include linear, quadratic, and cubic time trends. Table 1 presents summary statistics.

Table 1 Summary statistics

We employ negative binomial regression for models estimating the effects of taxation on the likelihood of coup activity due to the small number of coup events, and resulting overdispersion around the mean of the independent variables. In all models regressing coup activity on direct taxation, we estimate robust standard errors clustered at the country level. We use OLS with country fixed effects in the final set of models estimating the downstream impact of democratic breakdown on taxation. Footnote 73 In the next two sections we present our results.

Does Redistributive Taxation Catalyze Regime Breakdown?

We first estimate the effect of taxes on income, profits, and capital gains on the likelihood of democratic breakdowns. Table 2 estimates the determinants of coups against all regimes—not just democratic regimes. On the one hand, some redistributive arguments (including EODD) theorize that only democratic governments can make credible commitments to redistribute wealth, suggesting that the rich might only conspire to overthrow redistributive democracies. Alternatively, the wealthy might be equally motivated to overthrow a left-wing or populist dictatorship. Whereas such authoritarian regimes might not be able to credibly commit to redistribute to the poor, neither can they easily credibly commit to protect the property rights of the well-to-do.

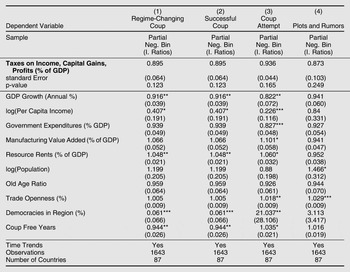

Table 2 Redistribution and regime breakdown (Dependent variables: Successful Coups and Count of Coup Attempts and Coup Plots and Rumors in Full Sample)

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. Robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. All independent variables lagged by one period. Linear, quadratic, and cubic time trends estimated but not reported.

Table 2 presents results for our full sample. Column 1 reports incidence-rate ratios and shows that taxes on income and capital gains profits are significant negative predictors of successful military coups. This poses an empirical challenge to the redistributive model. Controlling for economic performance, development, and a range of other covariates, the more that governments manage to collect taxes on income and capital gains profits, the more immune they appear to be to coups. The coefficient on direct taxes implies that increasing direct tax collection by one percentage point would be expected to decrease the rate of successful coups by a factor of 0.85 (p=0.01). Footnote 74 To clarify the result further, if the same specification is used in an OLS model with robust standard errors clustered by country, a one-percentage-point increase in direct taxes is associated with a 4.4 percent decrease in the probability of a regime-changing coup (p=0.08). Footnote 75 The negative correlation between coups and direct taxes thus appears to be both statistically significant and substantively important.

Similarly, successful coups (that do not necessarily change the regime) and attempted coups are negatively correlated with direct taxes. Increasing tax collection by one point decreases the rate of successful coups by a factor of 0.88 and attempted coups by a factor of 0.90. In the full sample, coup plots and rumors are also negatively correlated with direct taxes, but the coefficients are not statistically significant.

When we restrict attention to a substantially smaller dataset of democracy country-years in table 3 and examine data on a still smaller number of successful and regime changing coups, the coefficient on direct taxes is not significantly different from zero at standard levels (p=0.12) but is negatively signed. The coefficients on coup attempts and plots and rumors in this sample are also negatively signed. Footnote 76 Again, an important line of argument in the redistributive tradition is that only democratic government can provide the poor with a credible commitment to ongoing redistribution. Footnote 77 To the limited extent that these correlative models summarize a finding, it is that there is no support for this claim.

Table 3 Redistribution and regime breakdown (Dependent Variables: Successful Coups and Count of Coup Attempts and Coup Plots and Rumors in Democracies Only)

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. Robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. All independent variables lagged by one period. Linear, quadratic, and cubic time trends estimated but not reported.

Note: results in (1) and (2) are identical because successful coups in democracies also result in regime change.

There are two important implications of this initial finding, using data from both democratic and nondemocratic regimes. The first is that the wealthy do not appear to successfully agitate for military intervention, even when taxes collected from them are an increasing share of a country’s economy. The second is that the statistical evidence is consistent with our view that states with the capacity, and governments with the will, to extract taxes from the wealthy also appear capable of keeping army officers in the barracks.

Given these results, we take the upshot to be fairly clear: higher taxation of the rich does not foretell a greater likelihood of democratic breakdown. On the contrary: the data provide support for our argument that taxing the rich indicates a highly capable state administration, which insulates regimes from the risk of collapse. In short, more capable states tend to be less vulnerable to coups, and our quantitative findings here dovetail with the qualitative data we present below. But do coups against democracy have dividends for the rich in the years that follow them?

Do Post-Coup Regimes Tax the Rich Less?

Our second set of models estimate the effects of regime-changing coups—which the redistributive model expects to produce a drop in redistribution by restoring the political primacy of the upper class—on downstream taxation. Here we use a binary measure for regime-changing coups as the independent variable. While highly extractive and redistributive taxes might provoke coup attempts, it is only if the wealthy’s putative agents in the military succeed in seizing power that they can impose new pro-rich policies. The results here seem to disconfirm the logic of coups leading to lower redistributive taxes, just as our first set of analyses cast doubt on any argument that high redistributive taxes lead to coups.

We again estimated these models using different subsets of the data. The first includes the lagged coup independent variable. The second includes only nondemocratic regime years, as defined by Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland. Footnote 78 In this sample the consistently significant variable was level of economic development.

Table 4 essentially asks what, all else equal, are the downstream effects of a successful coup on taxation from the wealthy? The answer, robust to several different measures and looking at both the level and change in taxes, is very little. Coups have no significant impact on how much tax revenue regimes collect from their more well-to-do citizens. Again, there appears to be little support for the notion that armies serve as economic agents of the upper class. Footnote 79

Table 4 Coups and post-coup redistributive adjustment? (Dependent Variable: Taxes on Income and Capital Gains Profits as Share of GDP)

*** p<0.01 **p<0.05 *p<0.1. Linear, quadratic, and cubic time trends estimated but not reported.

In sum, these cross-national results provide some initial support for our state-centered account—but not for a redistributive account—of democratic breakdown. Yet these results have offered a summary of (a very large number of) snapshots, not a moving picture. In the next section, we provide additional evidence by process-tracing the historical dynamics of regimes and redistribution in what might be considered “crucial” cases for the redistributive model: the virulently anti-communist regimes that reigned in Southeast Asia’s “ASEAN-5” (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand) during the Cold War era.

Regimes and Redistribution in Southeast Asia

Like the redistributive model, our state-centered framework should be assessed by how well it explicates causal processes as well as final outcomes. Footnote 80 In this section we zoom in on Southeast Asia to trace how (1) different regimes have taxed elites, (2) military interventions and democratic breakdowns have unfolded, and (3) redistributive practices have altered in their wake. We begin by examining longitudinal data on direct tax collection from five capitalist Southeast Asian countries under both dictatorship and democracy during the Cold War era. We supplement this data presentation with brief case-studies of redistribution before the military-backed autogolpe that ushered in the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines, and after the coup that launched Suharto’s “New Order” military regime in Indonesia.

As noted earlier, these cases should be relatively “easy” ones for redistributive models to explain. Along with Latin America, Southeast Asia was the major regional home of pro-American, anti-communist dictatorships during the “second reverse wave” of democratic breakdowns. Footnote 81 Democracy had collapsed or failed to emerge in every country in Southeast Asia by the early 1970s, usually in the face of considerable leftist mobilization. Footnote 82 If right-wing backlashes against excessive redistribution were not the cause of authoritarian seizures of power in Cold War capitalist Southeast Asia, it seems unlikely that this framework would hold up to detailed historical tests in other regions.

Figures 1 and 2 provide taxation data from the five original members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a pro-American regional organization founded in 1967 as a collective security bulwark against the rise of communism. We exclude the region’s avowedly socialist dictatorships (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Burma), even though they would undoubtedly strengthen our argument that authoritarianism and redistribution from the rich can go hand in hand.

Figure 1 Weak state trajectories in Southeast Asia: Percentage of tax revenue from direct taxes 1947–1988

Sources: U.N. Statistical Yearbook, U.N. Economic Survey of Asia and the Far East, and Asher (1989).

Figure 2 Authoritarian leviathans in Southeast Asia: Percentage of tax revenue from direct taxes 1949–1988

Sources: U.N. Statistical Yearbook, U.N. Economic Survey of Asia and the Far East, and Asher (1989).

Note: Indonesia data include tax revenue from oil.

Two patterns are especially noteworthy. The first, most clearly displayed by the “weak-state trajectories” in the Philippines and Thailand in figure 1, is that cross-national divergence in fiscal capacity was already well established by the 1950s, due to differing state-building processes in the wake of World War II. These initial patterns proved resilient through the regime changes of the 1960s and 1970s, supporting our argument that redistributive taxation is more a function of (sticky) state capacity than (shifting) regime type. A second pattern of note is that these five countries did not reach their apogee of tax collection from economic elites during democratic times. This is most clearly seen in figure 2, where the “authoritarian Leviathans” of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore more successfully extracted taxes from economic elites than their more democratic predecessors.

As with our quantitative tests, we acknowledge that this mid-range test on ASEAN cases is only an imperfect test of the redistributive model. For starters, one might fairly question how democratic the three “authoritarian Leviathans” were before their decisive authoritarian crackdowns (1959 in Indonesia, 1965 in Singapore, and 1969 in Malaysia). Additionally, Thailand lacks the Philippines’ long and relatively uninterrupted democratic experience, and hence constitutes a relatively weak case of a non-relationship between democracy and downward redistribution. It is also noteworthy that authoritarian turns in Malaysia and Singapore did not directly involve the military, exemplifying the potential for empirical slippage between democratic breakdown and military intervention in the real world. Yet what is most important for our analytical purposes here is that progressive taxation increased in all three “authoritarian Leviathan” cases after these regimes became decisively more authoritarian and less populist in character, and that relative levels of elite extraction across Southeast Asia’s diverse regimes have generally been the opposite of what the redistributive model would predict.

Since we lack space to process-trace the evolution of redistribution and regimes in all five countries, we focus our historical attentions on two: the Philippines and Indonesia. The case of the Philippines shows that even a highly stable and deeply inegalitarian democracy need not be characterized by considerable redistribution, and that low levels of redistribution by no means inoculate a democracy against breakdown. Indonesia then shows how even a resolutely right-wing dictatorship can impose steeper redistributive taxation than its left-wing predecessors, since extraction from the wealthy in the postcolonial world is less a function of ideology or regime type than of state capacity.

Democratic Breakdown Absent Redistribution: The Philippines, 1946–72

No country in Southeast Asia has had a longer experience with democratic politics or has suffered steeper income inequality than the Philippines. Yet Philippine democracy has never developed the redistributive character that so many political economists expect to emerge in democratic regimes under unequal conditions. Far from representing a collective elite effort to overturn democratic redistribution, the Philippines’ democratic collapse was inspired in part by a dictator’s desire to extract more resources from the economic elites who had thrived unmolested under electoral democracy.

The Philippines gained independence in 1946 with all the procedural democratic trappings of their erstwhile American occupiers. Yet since administratively challenging direct taxation is primarily a function of state capacity rather than regime type, the fledgling Philippine democracy made no initial headway at sinking its fiscal teeth into the oligarchic elite—commonly derided as “the caciques.” Despite being stricken with among the steepest income inequality in Southeast Asia (refer to figure 3), the Philippines would not see democracy give rise to significant downward redistribution. To begin to understand why, consider how two tax economists summarized the parlous state of the Philippines’ Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) after independence:

The number of people with incomes sufficient to require filing of reports increased greatly after the war, and yet the government had neither space nor equipment adequate to take care of the needs. The filing system was so inadequate that taxpayers’ records could not be found, and many of the assessments and payments remained unposted for years. Provincial treasurers often failed to send in reports, and the Bureau was in no position to press for effective compliance. Assessment notices, unposted receipts, and other papers were literally piled up in filing cabinets, desk drawers and boxes, and on shelves, cabinets and on the floor. In brief, no one knew to what extent the tax liabilities of the postwar period had been paid. Footnote 83

Figure 3 Gini coefficients for Asean 5 nations

Source: Deininger and Squire Reference Deininger and Squire1996.

Median voters thus lacked an effective state apparatus through which to redistribute income from the oligarchy to themselves. The success of economic elites at using democracy for their own purposes was poignantly captured in a 1952 report on “rampant tax evasion” in The Philippines Herald: “Two-thirds of the representatives of Congress were not assessed; and of the 24 senators and 10 Cabinet members, only eleven were assessed income taxes.” Footnote 84 Given the strong correlation between personal wealth and electoral office in the Philippines, this provides a vivid picture of the BIR’s incapacity to collect income taxes from the nation’s elite. Democracy was not helping the Philippine citizenry demand more redistribution from the oligarchy; it was allowing the oligarchy to secure elected office and protect itself from state extraction.

The scales would tip slightly in the state’s favor with the political ascendancy of the Philippines’ first non-oligarchic president, Ramon Magsaysay, in 1953. “Shortly after his inauguration, President Magsaysay directed that [sic] National Bureau of Investigation to examine into the many charges of corruption in the Bureau of Internal Revenue. After its initial investigation the NBI decided to maintain a permanent staff of agents in the Finance building.” Footnote 85 Yet his bid to clean up the tax bureaucracy was strikingly limited in both its scope and duration. Taxes stayed mired below 10 percent of gross domestic product throughout the 1950s, with direct taxes generally comprising around 20 percent of that paltry total.

The 1954–1965 period was “the full heyday of cacique democracy in the Philippines.” Footnote 86 In fiscal terms, this was expressed in the steadfast refusal of the Philippine Congress to countenance any increase in direct taxes. To get a sense of this congressional resistance, one can examine the most concerted presidential effort to impose tax authority over the Philippines’ cacique class during this period. In 1963, President Diosdado Macapagal, like Magsaysay a president of relatively humble origins, fought tooth-and-nail to pass his Agrarian Reform Act, which “provided for the abolition of tenancy,” through a predictably hostile Congress. While Macapagal won the battle, he lost the war, as Congress “squeezed a trade-off—the elimination of the taxation plan that would finance the program.” Footnote 87

As economist Edita Tan summed up the situation in 1971, on the eve of martial law, “There has been a heavy reliance on indirect taxes which are inherently regressive. The progressive taxes have been ineffectively collected.” Footnote 88 This reflected the inability of Ferdinand Marcos, first democratically elected to the presidency in 1965, to improve upon his predecessors’ fiscal performance. By raising corporate and luxury tax rates and introducing a new fixed tax on professionals with annual incomes exceeding six thousand pesos, Marcos seemingly laid the groundwork for a moderately more progressive tax system. But compliance remained elusive, with leaders of the Chamber of Commerce and sectoral business associations publicly decrying the new levies as “excessive,” “ruinous,” “oppressive,” and “confiscatory.” Footnote 89 Congress grudgingly authorized special taxes on travel and stock transfers in late 1970; yet when this failed to extract much revenue from those select Filipinos with ample resources to take vacations and own stocks, Congress reverted to its normal, regressive approach, proposing to double the tax on beer to make up the difference. Footnote 90 In sum, Marcos’ efforts to tax the rich in this democratic period proved Sisyphean rather than Herculean, as collections of income and corporate taxes remained flat from 1969 to 1972.

Marcos’ frustrations with the oligarchy’s intransigence better explain his connivance with military officers to impose martial law in September 1972 than shared elite fears of redistributive pressures from below. Footnote 91 Indeed, Philippine democracy had proven amply capable of absorbing any and all popular pressures for more extensive redistribution. Democratic collapse in the Philippines would be a product of a self-aggrandizing president and his opportunistic military allies aiming to overcome the Philippine state’s historical pattern of subservience to economic elites, not a joint elite project to stifle mass politics and suppress redistributive demands. Footnote 92 Since Marcos inherited and commanded such a weak state apparatus, however, he enjoyed little more success at extracting revenue from elites after the 1972 coup than he had beforehand (refer to figure 1). The same cannot be said of Indonesia’s Suharto, who seized power as a state-builder as well as a dictator.

Redistribution under Right-Wing Authoritarianism: Indonesia, 1966–1975

Right-wing dictatorships may have been uniformly brutal toward communists during the Cold War era, but they did not automatically do the bidding of capitalists. The dynamics of redistribution after the seizure of power by Lt. General Suharto in Indonesia in 1966 illustrate this point. Consistent with our aggregate analysis suggesting no systematic tendency for post-coup authoritarian governments to reduce or reverse redistribution from rich to poor, Indonesia provides a striking example of military autonomy from moneyed interests as well as the critical importance of state capacity for effective redistribution. Following Suharto’s ascent to the presidency, his military-centered regime engaged in a hurried state-building project that included a marked expansion of its capacity to extract revenues from wealthy Indonesians, and to target public goods (on the heels of massive levels of deadly repression) toward restive popular sectors. Suharto’s “New Order” was launched as a coalition between colonels and civil servants, with capitalists following orders rather than giving them.

Procedural democracy actually broke down in Indonesia well before Suharto took power, however. From 1957–59, in the face of a stalemated democratic constitution-drafting process and a rising tide of regional military rebellions, Sukarno replaced parliamentary democracy (1949–1957) with what he oxymoronically dubbed “Guided Democracy” (1957–1965). Contra the redistributive model, it was only after Sukarno’s cancellation of democratic procedures that Indonesian politics took a radically leftist, anti-elitist turn. As in the weak-state Philippines, democracy in weak-state Indonesia had meant precious little redistribution to the deeply impoverished majority of median voters. And Sukarno strove to build a dictatorship of the many, not the few. Footnote 93

Suharto’s right-wing military takeover of 1965 appears at first glance to offer much more support for the redistributive approach to regime breakdown. Sukarno’s “Guided Democracy” was a time of looming leftist revolution and virtual state collapse. The Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) had become the world’s third largest and was increasingly destabilizing rural and urban areas alike. State revenues came to a halt as tax collection deteriorated and Western fears of Sukarno’s communist leanings led to the collapse of oil purchases. This political and economic crisis culminated in the kidnapping of conservative army officers by radical lower-level officers with alleged ties to the PKI. Suharto, stationed in Jakarta, responded by ordering army units to take up positions around the city, beginning a process that led to the killing of hundreds of thousands of suspected communist sympathizers and to his assuming the presidency. Footnote 94

According to the redistributive model, such an unabashedly right-wing military takeover following increasingly radical lower-class mobilization should have led to less redistribution from the rich to the poor. Something quite different took place, however. The Sukarno years had been characterized by the rhetoric more than the reality of redistribution, given the conditions of state collapse under which Sukarno had struggled to accomplish any tasks, much less the highly challenging tasks of fiscal extraction and redistribution. Hence the Suharto regime’s immediate concern was not to roll back the state, but to build it back up.

This included bolstering the state’s extractive institutions. Oil revenues began to accrue again after 1966 but did not become a major portion of total government revenues until 1974. What happened during these eight years was quite surprising from the perspective of the redistributive model of regime politics: even as Suharto’s New Order generated strong political support from economic elites due to its success at crushing the PKI, it simultaneously increased its fiscal extraction from precisely those elites. Indonesia’s upper classes had not been forced to accept democratization to stave off leftist revolution, as expected in the redistributive model, but they did need to countenance the construction of a far stronger and more extractive authoritarian Leviathan. Footnote 95

The aggregate figures for government revenues provide a striking first cut at the speed with which the Suharto government worked to put the state's fiscal affairs back in order. During the first year of Suharto's New Order, national tax revenues increased 600 percent and by as much as 1,700 percent in former communist strongholds such as Yogyakarta in central Java. A look at total government revenues between 1965 and 1968 reveals an immense spike in revenues of 2,000 percent. Footnote 96 Even when we discount that increase to account for the substantial inflows of international aid starting in 1967, the rise is remarkable, speaking strongly to the immediate efforts of the New Order regime to rebuild the state's extractive capacity. In addition, personal income tax collection rose at a consistent rate each year during the decade. Even though such progressive taxes remained a small percentage of total collection, Footnote 97 in large measure because of the easy taxability of Indonesia’s natural-resource sectors, there is no question that rich Indonesians were taxed more effectively after the right-wing military takeover of 1965–66 than beforehand.

The emergence of a more capably interventionist and extractive state was witnessed at the local level as well as nationally. Footnote 98 Schiller notes, for instance, a marked increase in local revenues to the Jepara district government, on the north coast of Central Java: "Between 1969–70 and 1980–81 Jepara local[ly derived] government revenues grew from Rp.49.7 million to Rp.574.9 million-an eleven-fold increase in 11 years." Footnote 99 In Jepara and in most of the rest of the country, institutional capacity grew with the economy: "All respondents in Pemda [pemerintah daerah , local government] believed that more information is more accurately collected than at any time in their careers." Footnote 100 The steady increase in tax revenues, along with total government revenues in the five years following Suharto's rise to power, suggest a concerted effort to build state capacity across Indonesia. This effort simultaneously led to an array of new spending policies aimed at mitigating the threat of lower-class mobilization. Footnote 101 The New Order rested not simply on an elite pact, but on the building of a stronger, state-centered social safety net for Indonesia’s poorest citizens.

The early years of Indonesia’s New Order military rule thus illustrate how postcolonial state apparatuses shape the dynamics of redistribution and regimes. Armies more often seize power with an eye on bridling general social instability and asserting their autonomous interests than on shifting redistribution to more rich-friendly levels. Even when we witness a strong political alliance between economic elites and military elites, as in New Order Indonesia, the military is likely to be holding the whip hand. The wealthy do not only tend to support military rule when it means a reduction of economic redistribution, but when it promises a restoration of political order. Yet the price of order sometimes includes the construction of a stronger state with new-found capacity to extract from the wealthy in fiscal terms, even as it protects them in physical terms.

Conclusion: State Power and Democratic Defense

In the final analysis, the policy prescriptions logically entailed in the redistributive model seem to us to be paradoxical. On the one hand, economic policies that fulfill the interests and wishes of the majority are taken to be a definitional entailment of democratic politics. But if the new democracy can only survive by curtailing its purported redistributive appetites, how are citizens to gain the “good coat . . . . hat . . . . roof” and “good dinner” Footnote 102 that ostensibly make them want democracy in the first place? If democracy fails to deliver the goods, would this not imply a subsequent loss of public concern with sustaining democracy? And if the citizens cease to favor a regime type that supposedly serves nobody but them, who will step forward to support it?

We interpret the problem of democratic defense quite differently. If unhappy soldiers are the biggest proximate threat to democracy, then soldiers should be reasonably well paid, well treated, and well equipped to help encourage and sustain their political subservience. If apathetic citizens leave democracy highly exposed to authoritarian conspiracies, their interest in popular rule should be cultivated with valued public goods. And if desperate economic times lead a wide variety of citizens to cry out for (or at least acquiesce to) desperate political measures, macroeconomic management must be sufficiently professional and competent to smooth out the financial swells and troughs that revisit postcolonial countries on a recurrent basis.

From this perspective, our (unsurprising) finding that economic downturns are correlated with anti-democratic coups does not mean that political scientists should be looking for economic rather than political origins of democratic breakdown. Footnote 103 As the literature on “developmental” and “predatory” states has taught us, Footnote 104 economic performance in the postcolonial world is endogenous to state capacity. That economic crisis raises the likelihood of democratic breakdown is proximately true; but this threatens to obscure the deeper point that politics and economics exhibit something of a whipsaw effect, in which underlying political fragilities spark and worsen economic downturns, which undermine struggling political regimes in turn. Political scientists would thus do well to research further the political underpinnings of economic stability and instability.

In our view, this search to uncover the political origins of democratic breakdown in the contemporary world leads inexorably to that political creature so often afflicted by autonomous militaries and incapable bureaucracies: the postcolonial state. Whenever we think of the tasks a democracy must accomplish to survive against its authoritarian rivals, we see tasks that require the existence of a capable state, not a limited one. Effectively managing a small but financially interdependent economy is all but impossible without a Weberian bureaucracy at the administrative helm. Footnote 105 Delivering valued side-payments to broad political constituencies requires bureaucratic coherence as well as a socially embedded state apparatus. Footnote 106 Paying and equipping a modern military requires revenue, and there has been no greater money-earner for the modern state than direct income taxes. Footnote 107 In sum, the best way for a fragile democratic government to survive would not seem to be by keeping its hands off of local private fortunes, but by developing the institutional capacity to stake a claim to its fair share of them on behalf of the sovereign public.

Supplementary Materials

-

Explanatory File

-

Appendix Tables 1A–1F

-

Replication Files