The wedding of the pro-life movement with the Republican party has been a defining feature of contemporary party platforms. Over a short period of time, abortion shifted from being an issue that fell outside the political arena to one that has deeply divided the parties and symbolized a political culture war.

How did Republicans end up as the pro-life party? Among the mass public, Republican identifiers in the electorate expressed modestly more liberal abortion attitudes than Democratic identifiers until the late 1980s. Footnote 1 Furthermore, economic issues, which defined party conflict in the post-New Deal era, have historically had little relationship to abortion attitudes (Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002, 60; refer to the section on economic issues in the Supplementary Appendix). Despite this, Republican members of Congress were to the right of congressional Democrats on abortion policy by 1973, and by 1980, so too were the major presidential candidates (Adams Reference Adams1997; Karol Reference Karol2009).

Consistent with these observations, leading scholarship approaches party coalition formation on abortion as a top-down process. These theories emphasize that politicians and antiabortion activists played the decisive role in aligning the antiabortion movement with conservatism and the Republican party; voters belatedly followed along (Adams Reference Adams1997; Bawn et al. 2012; Layman Reference Layman2001; Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey, Green, Herrera and Cooperman2010; Noel Reference Noel2013). A crucial implication of this scholarship is that elite actors could have constructed the alternative outcome and bundled antiabortion views with liberal causes inside the Democratic party.

I argue that ordinary voters played a larger role in determining the parties’ relative abortion position than existing literature suggests. Footnote 2 Among the mass public, latent antiabortion views already correlated to conservative views on a range of noneconomic issues, such as civil rights, Vietnam, and broader conservative identification, before the parties staked a clear abortion position. Consequently, once the parties began to divide on race and Vietnam, events which preceded abortion’s attainment of political salience, issue connections among ordinary voters made it easier for Republicans to oppose abortion once it became politically activated. Likewise, because proabortion voters generally supported civil rights, once the GOP became the party of the South, this predisposed the proabortion movement to align with the Democratic Party. This occurred despite prominent politicians from both parties taking diverse positions on abortion policy and many early antiabortion activists’ desire to ally with Democrats.

This theory pivots from existing accounts by emphasizing that abortion gained salience in a partisan political environment that was no longer defined only by New Deal economic intervention. Social turbulence over race, Vietnam, and other cultural issues had begun to transform partisan coalitions before abortion became activated. Indeed, it is the lack of a meaningful relationship between abortion attitudes and economic attitudes that paved the way for elites to exploit abortion’s connection with other noneconomic issues (because economic issues did not act as a countervailing force).

This article explores the role of voters, interest groups, politicians, and public intellectuals in linking the antiabortion movement with conservatism and the Republican party. I argue that top-down theories should be modified to allow a greater role for voters.

The article proceeds in four main parts. First, I show that conservative abortion attitudes have long correlated with conservative attitudes on essentially every other noneconomic issue and that these issue connections existed before the parties polarized on abortion policy. Furthermore, by the early 1970s, those voting for Republican presidential candidates were marginally more conservative on abortion than Democratic voters.

Second, relying on original archival research and secondary accounts, I argue that preexisting mass-level linkages hindered organized efforts by the early pro-life movement to enter the Democratic party or connect their cause with progressive issues. This is despite leaders of the pro-life movement’s explicit efforts to do so (Williams Reference Williams2016; Ziegler Reference Ziegler2015). I then contrast the struggles of the early pro-life movement with the later success of the Christian Right. I argue that Christian Right leaders in the late 1970s exploited preexisting issue connections among ordinary voters to build a social movement that articulated antiabortion views in a web of conservative causes. A key point is that while national evangelical leaders stayed quiet or supported moderate to liberal abortion reform in the early 1970s (in part because they viewed it as a Catholic issue and thus undesirable), the evangelical laity expressed similarly conservative abortion attitudes as white Catholics by the late 1960s. Footnote 3

Third, I argue that leading politicians were mindful of how positioning on abortion aligned with constituencies already inside their party and with constituencies they perceived to be up for grabs. Issue overlap between abortion and policies that already divided the parties, such as Vietnam and civil rights, created an environment that made it easier for Republicans (Democrats) to pursue anti (pro) abortion voters, even when those positions ran contrary to the demands of interest groups (see also Carr, Gamm, and Phillips Reference Carr, Gamm and Phillips2016).

Fourth, I explore the early abortion views of conservative media figures (see Noel Reference Noel2013). I find that prominent conservative intellectuals initially expressed a diverse range of abortion positions before they belatedly aligned their public views with the conservative movement.

Although this article primarily focuses on the Right, the alignment of Democrats with the pro-choice movement and feminism was similarly circuitous: abortion rights divided feminist organizations in the late 1960s, and the early pro-choice movement crosscut ideological and partisan lines. Furthermore, because the Democratic Party still included large socially conservative constituencies, leading Democrats, including George McGovern, avoided sending clear signals on the issue in the 1970s (Friedan Reference Friedan1976; Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1991; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000).

Although focused on only a single (albeit salient) issue, this account speaks to a central debate regarding contemporary polarization and the relative role of elite- versus mass-level forces (for example, see Bawn et al. 2012; Caughey, Dunham, and Warshaw Reference Caughey, Dunham and Warshaw2018; Chen, Mickey, and Van Houweling Reference Chen, Mickey and Van Houweling2008; Karol Reference Karol2009; McCarty and Schickler Reference McCarty and Schickler2018; Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1997). Rather than elites constructing the ideological space, this evidence suggests that a prominent constellation of issues in the mass public preceded elite action.

Existing Views: Party Positioning on Abortion

Scholars commonly note that the correlation between partisan identification and abortion attitudes among voters was effectively zero until the early 1990s, at which point Democrats began to favor fewer abortion restrictions than Republicans (Adams Reference Adams1997). This observation underpins two leading theories of party positioning on abortion, both of which emphasize that elites, not voters, were the critical actors. First, Adams (Reference Adams1997) argues that party positioning on abortion fits with Carmines and Stimson’s (Reference Carmines and Stimson1989) theory of “issue evolution.” In an issue evolution, partisan change occurs slowly over time, and at critical junctures party leaders stake out their party’s new position. On prominent issues, this new positioning then becomes a distinguishing cleavage between parties that trickles down to activists and finally voters. A critical implication of issue evolutions is that party leaders have discretion and that elites of either party could have adopted the antiabortion view.

The second theory argues that interest group leaders and their activists initiated the parties’ abortion positions (Bawn et al. 2012; see also Cook, Jelen, and Wilcox Reference Cook, Jelen and Wilcox.1992, 170; Layman et al. Reference Layman, Carsey, Green, Herrera and Cooperman2010; Zaller Reference Zaller2012). This scholarship argues that voters’ lack of attention gives interest groups the flexibility to nominate candidates who take positions that diverge from the median voter. For example, Karol (Reference Karol2009) sketches a compelling portrait of leading politicians who flipped their abortion views to appease various policy-demanding groups from the 1970s onward. Likewise, Schlozman (2015, 102) argues that mid-level political entrepreneurs played a critical role in linking evangelicals, race, taxes, and abortion within the Republican Party (see also Layman Reference Layman2001). Footnote 4

Other theories, although less explicit in terms of party position change, also elaborate the importance of elite leaders in shaping public opinion and ideologies. Noel (2013, 158–63) argues that opinion leaders at prominent magazines and newspapers played a leading role in integrating abortion with other policy views into an ideological package. Footnote 5 Franklin and Kosaki (Reference Franklin and Kosaki1989) find that the Roe v. Wade ruling influenced public opinion by legitimizing abortion in traumatic cases, such as pregnancy due to rape, and polarized abortion opinion in discretionary cases, such as when a mother did not want more children.

Taken together, this literature points to the powerful effect that elite actors have on shaping abortion attitudes of the rank and file. Yet understanding party positioning (and change) primarily in terms of interest groups or politicians leaves key questions unanswered. First, politicians are both strategic and risk averse; why upend public opinion if it is easier to follow prevailing trends? Second, abortion is a symbolic and emotional issue that shapes partisan attachments and is less malleable to elite signaling (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz1995; Carsey and Layman Reference Carsey and Layman2006; Killian and Wilcox Reference Killian and Wilcox2008). Third, how do intense policy demanders choose one party over the other? Pro-choice (Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000, 35; Young Reference Young2000, 34) and pro-life activists initially tried to—and would have preferred to—align with both parties in the 1970s (refer to the later section, “Interest Groups”).

This article argues that examining voter behavior helps fill these gaps: issue overlap in public opinion between abortion attitudes and noneconomic issues enabled Republicans to oppose abortion rights and for pro-life groups to ally with the GOP.

Theory

The activation of salient social issues—most prominently civil rights, race, and Vietnam—as a partisan cleavage narrowed the set of options for party positioning on abortion. Central to this theory is the fact that conservative abortion attitudes are tied to conservative attitudes on a host of other noneconomic issues. Consequently, once racial conservatives and Vietnam hawks began entering the Republican Party, it became easier for the GOP to oppose abortion rights. Likewise, because supporters of abortion rights tended to also support civil rights, when the Republicans became the party of the South, this predisposed the women’s rights movement (which itself was divided on supporting abortion rights; refer to the later section on pro-choice feminism) into the Democratic Party (Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000; Young Reference Young2000, 29).

The next section outlines why Republicans saw race as a critical opportunity to expand their coalition and then describes why the introduction of race as a partisan cleavage made it easier for Republicans to oppose abortion rights.

Activation of Race as a Partisan Cleavage

Entering the 1960s, Democrats and Republicans held overlapping policy positions on civil rights. This overlap was partially strategic: to avoid splitting their broad New Deal coalition, which included both Southern whites and African Americans, national Democratic leaders sought to keep civil rights off the agenda.

However, mounting pressure from the growing civil rights movement upended this equilibrium. The number of African Americans and the Democrats’ racially liberal wing were growing, and to forestall a liberal challenge for the presidential nomination in 1964, Lyndon Johnson saw embracing racial minorities as essential (Schickler Reference Schickler2016, 232). Johnson aggressively pursued landmark civil rights legislation that cemented Democrats’ reliance on (and allegiance from) black voters and other racial liberals. Footnote 6

The national Democrats’ embrace of racial minorities, which alienated the white South and other racial conservatives, presented an opportunity for the Republican Party. Conservative operatives believed that blue-collar and white-collar workers, despite holding divergent economic preferences, could be united behind an increasingly salient cross-class opposition to the racial and cultural liberalism of the 1960s. If the New Deal coalition had suppressed diverging racial interests of the white South and African Americans to pursue mutual economic interests, the turbulent 1960s presented an opportunity for increasingly salient social cleavages to override potential economic differences (Phillips Reference Phillips1969; Rusher Reference Rusher1975). Operatives referred to this coalition as the “New Majority.” Not only did it present an opportunity, some viewed the formation of this new coalition as necessary for conservatism to succeed. Footnote 7

An important feature of the conservatives’ New Majority coalition was the absence of African Americans. The Democratic Party’s clearly liberal stake in the civil rights movement meant that Democrats had effectively captured African Americans (Frymer Reference Frymer2010). “We’re not going to get the Negro vote…in 1964 and 1968, so we ought to go hunting where the ducks are,” Barry Goldwater remarked in reference to winning over white Southerners (qtd. in Masket Reference Masket2017). Republican candidates of the 1960s and 1970s shared this view and made little effort to appeal to black voters.

Implications for Abortion Positioning

I argue that, once Republicans pursued and began to successfully capture racially conservative constituencies, this created a domino effect that limited Republicans’ ability to position itself on abortion. This is because conservative constituencies on civil rights, Vietnam, and other noneconomic issues also tended to oppose abortion. Consequently, as racial and defense hawks began to enter the Republican Party, events that preceded the political activation of abortion, it became easier for Republicans to oppose abortion once the issue gained political salience.

To illustrate this claim and how it differs from existing views, consider two hypothetical scenarios. In Scenario A, imagine where civil rights has not been activated as a partisan cleavage—that is, the South stays in the Democratic Party—and the parties perfectly divide along economic lines. Furthermore, assume economic attitudes are perfectly orthogonal to abortion attitudes (Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002, 60; refer to the Supplementary Appendix section on economic interests). With respect to the Republicans’ economic position, activists or party leaders can take the party in either direction without concern that their abortion position would, on average, cross-pressure voters along the economic cleavage.

Now consider hypothetical Scenario B, in which an exogenous shock introduces a racial cleavage which instantly engenders a partisan realignment that divides the parties in the electorate perfectly by attitudes toward civil rights. Furthermore, assume that those who are conservative on civil rights are also more conservative on abortion (as I show in the next section). Now what happens when abortion becomes politically activated? Because the racial cleavage overlaps preexisting opinion on abortion, when abortion becomes salient, antiabortion voters are already inside the Republican Party, and proabortion voters are already inside the Democratic Party. Consequently, it becomes less costly for Republicans to oppose abortion rights. Similarly, this electoral environment makes it easier for pro-life interest groups to work inside the Republican Party. Indeed, because abortion attitudes lack a meaningful relationship to economic attitudes, this paves the way for elites to exploit abortion’s connection with race and other noneconomic issues (as economic issues do not act as a countervailing force). Of course, racial realignment took years. Issue overlap meant that Republican antiabortion appeals both satisfied voters already inside the party and attracted new voters with conservative views on both race and abortion.

Finally, although the argument is symmetrical, the two parties’ willingness to politically activate abortion was uneven. Because abortion divided Democrats more than Republicans, Nixon, Ford, and particularly Reagan saw an advantage in establishing a position on abortion as doing so would split the Democrats’ coalition. For that same reason, early Democratic nominees, including George McGovern, skirted around the issue (Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000, 37; Young Reference Young2000, 92; see the later discussion on Democratic politicians).

Mass Opinion

This section presents data that shows that ordinary voters who express conservative abortion attitudes also express conservative views on essentially every other noneconomic issue. These issue connections predate the parties’ establishment of distinct abortion positions. (Although I use the word “conservative,” the reverse is also true: more liberal attitudes on noneconomic issues are tied to more liberal abortion views.)

Data

I used data from the 1972, 1976, and 1980 American National Election Surveys (ANES), which are the first years the ANES included questions on abortion. Because the parties lacked clear abortion positions through much of the 1970s, these data also provide insight into the set of electoral incentives facing politicians before partisan divides crystallized.

From 1972 to 1980, the ANES asked respondents their attitudes toward abortion on a 4-point scale, ranging from those who believe abortion should always be allowed to those who believe it should not be allowed in any circumstance. I label respondents as conservative if they oppose abortion in all cases or believe abortion is acceptable only in instances where pregnancy endangers the life and health of the mother. I label respondents as liberal if they indicate abortion should be allowed in all cases or when personal reasons would make caring for a child difficult. This dichotomization helps aid interpretation and represents a substantive cut point of abortion fights in the 1970s. Although the initial abortion controversy in the 1960s centered on whether abortion should be allowed in any circumstance, the political fights by the late 1970s were around whether abortion should be allowed beyond traumatic cases (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Jelen and Wilcox.1992; Franklin and Kosaki Reference Franklin and Kosaki1989).

To differentiate between “liberals” and “conservatives” on the nonabortion questions, I coded all respondents who are left of center on each question as liberal (0) and those who are right of center as conservative (1).

Footnote 8

I then regressed abortion attitudes on the binary indicator of the secondary variable such as school busing, Vietnam, and pollution control. This is represented by the following regression model:

![]() $Abortio{n_i} = \alpha + {\beta _1}{X_i} + {\varepsilon _i}$

. The regression coefficient

$Abortio{n_i} = \alpha + {\beta _1}{X_i} + {\varepsilon _i}$

. The regression coefficient

![]() $\left( {{\beta _1}} \right)$

simply represents the difference in the proportion of abortion conservatives between, for example, busing liberals and busing conservatives.

Footnote 9

$\left( {{\beta _1}} \right)$

simply represents the difference in the proportion of abortion conservatives between, for example, busing liberals and busing conservatives.

Footnote 9

Issue Bundles

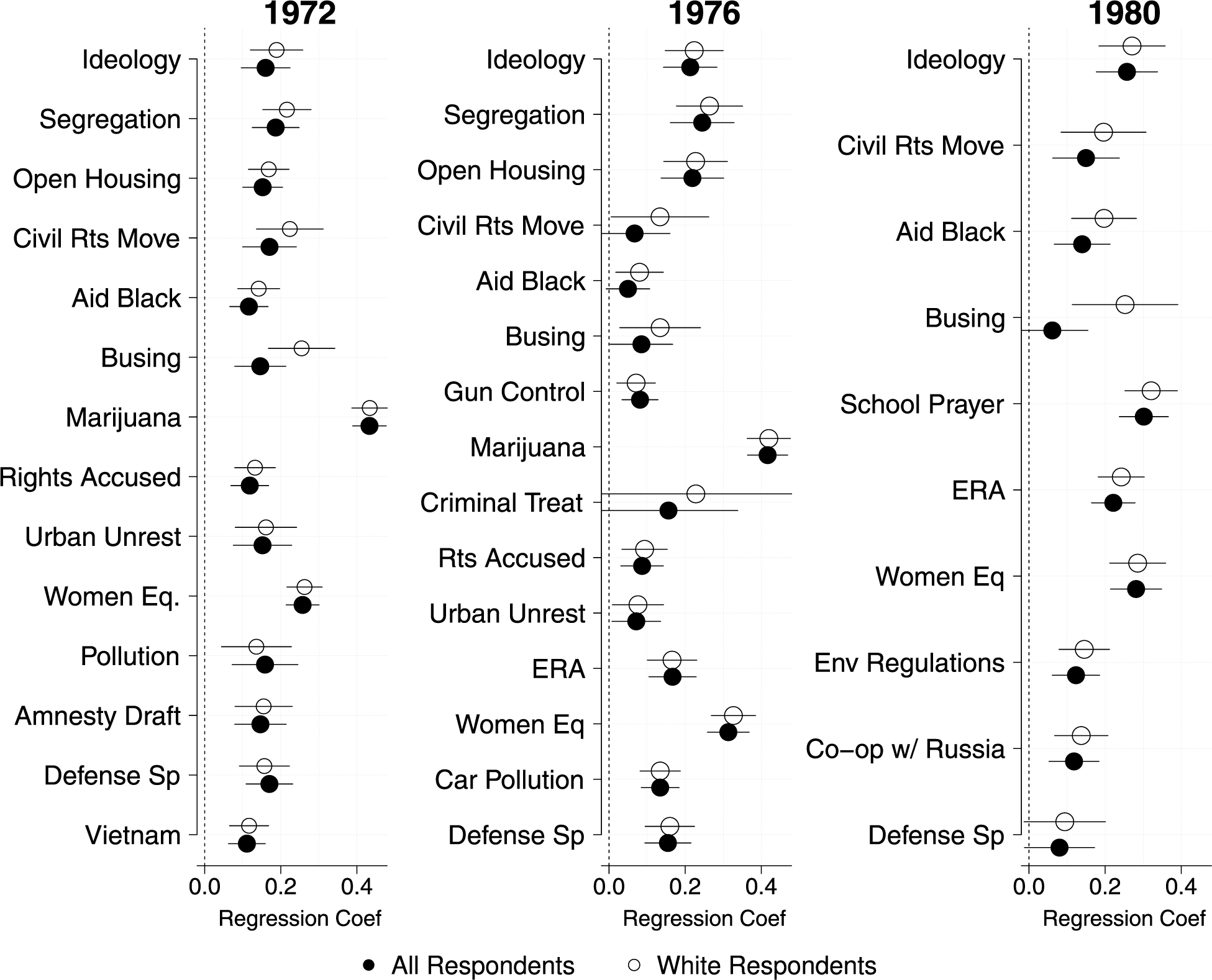

Figure 1 shows that across nearly every noneconomic issue on the ANES, respondents who expressed conservative (liberal) positions on other issue attitudes were more likely to express a conservative (liberal) abortion position too (refer to the Supplementary Appendix section, “Question Wording,” for details of each variable).

Figure 1 Issue Bundles

Notes: Black points are results for all respondents; open circles are for white respondents only. Using the bivariate regression equation,

![]() ${\rm{Abortio}}{{\rm{n}}_{\rm{i}}} = {\rm{\alpha }} + {{\rm{\beta }}_1}{{\rm{X}}_{\rm{i}}} + {\varepsilon _{\rm{i}}}$

, positive values mean that respondents who are, for example, conservative on defense spending on average take more conservative abortion positions too. Lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

${\rm{Abortio}}{{\rm{n}}_{\rm{i}}} = {\rm{\alpha }} + {{\rm{\beta }}_1}{{\rm{X}}_{\rm{i}}} + {\varepsilon _{\rm{i}}}$

, positive values mean that respondents who are, for example, conservative on defense spending on average take more conservative abortion positions too. Lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

For example, the top-left regression coefficient in figure 1 (in the 1972 panel) shows that respondents who identify as having a broadly conservative ideology are 16 percentage points more likely to express a conservative abortion view than those who identify as liberal. Footnote 10 Across questions related to race, racial conservatives are consistently more likely to oppose abortion than racial liberals. For example, the second point in the top-left panel shows those who favor segregation are 19 percentage points more likely to take an antiabortion position than those who oppose segregation in 1972. Attitudes on legalizing marijuana have the largest overlap with abortion attitudes: those opposed to legalization are 43 percentage points more likely to take a conservative position on abortion in 1972.

However, as previously discussed, the Republican Party’s appeals focused on white voters. The racial and economic liberalism of national Democrats by the late 1960s had locked African Americans into the Democratic Party, leaving the parties to compete for white “swing voters” (Frymer Reference Frymer2010). Footnote 11 For this reason, figure 1 also plots issue bundles for white respondents only. The relationship between issue attitudes looks similar, if not slightly larger among white respondents, than it does for all respondents. Footnote 12

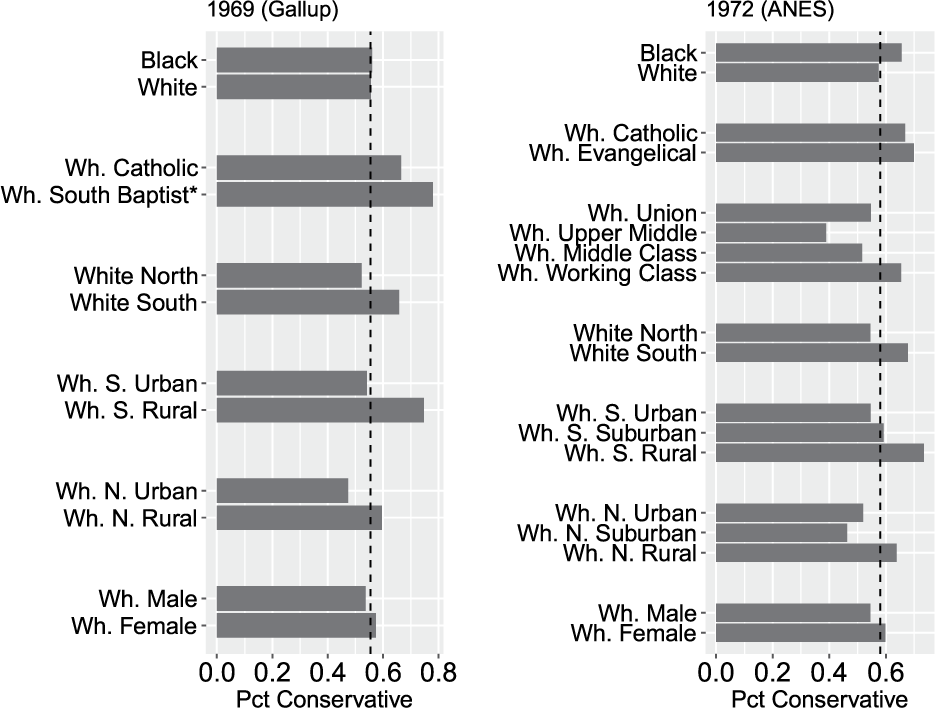

Abortion Attitudes by Group

Figure 2 splits abortion attitudes by salient political constituencies. Most noticeably, white evangelicals expressed positions on abortion that were as conservative as those of white Catholics by the 1972 ANES. Even earlier, a Gallup survey in 1969 showed that 77% of white Baptists in the South opposed elective first-trimester abortions compared to just 66% of white Catholics. Footnote 13 Furthermore, by 1969 the white South, a region that became crucial to the GOP’s success, took quite conservative positions on abortion too, as did rural areas compared to urban areas.

Figure 2 Abortion Attitudes by Group

Notes : Bars reflect the average abortion position for each subgroup. Values to the right are more conservative. The dashed line represents the average position. In the left-hand panel, Gallup asks respondents whether they would favor a law that allowed abortion in the first trimester. Those who answer no are labeled “conservative,” and those who answer yes are labeled “liberal.” Unsure responses are not included. In the right-hand panel, I label a conservative response as those who believe abortion should never be allowed or only when pregnancy endangers the life and health of a woman. (*Because Gallup does not ask for a specific denomination, I proxy white Southern Baptists as white Baptists living in the South. See Ammerman (Reference Ammerman1990)).

These observations have critical implications. First, the Christian Right did not mobilize around abortion until the late 1970s, meaning conservative abortion views predated mid-level activism among evangelical leaders. Second, when white Southerners migrated to the Republican Party on account of backlash to racial liberalism, they clearly brought with them their conservative positions on abortion too. By the time abortion had become salient in the 1980s, the Republican Party’s electorate already contained a large and conservative constituency on the issue. Footnote 14

Vote Choice

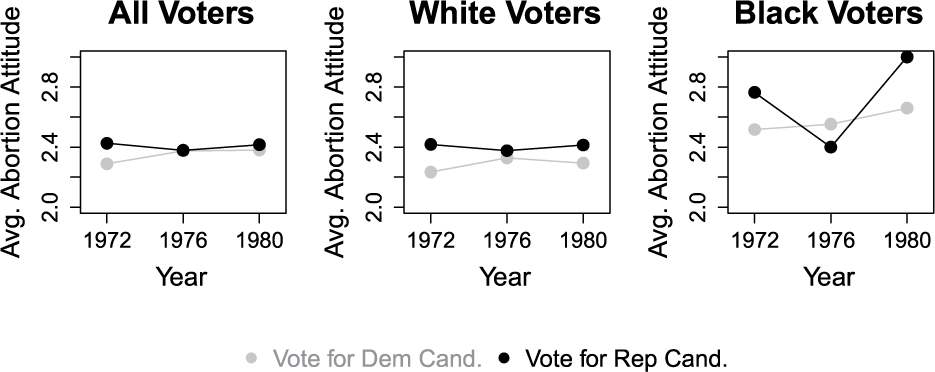

The result of Nixon’s Southern strategy and the Republican Party’s efforts to incorporate the New Majority meant that, by the 1972 election, although Republican identifiers might be more liberal than Democratic identifiers on abortion (Adams Reference Adams1997), those voting for Republican presidential candidates were more conservative on abortion than those supporting Democratic presidential candidates. Racial realignment meant that partisan identification in this era poorly predicted party support. Notably, many white Southerners by the 1970s supported Republican presidential candidates yet identified as Democrats or Independents.

Figure 3 maps abortion attitudes by presidential vote choice. The largest divide emerged in 1972, narrowed in 1976, and then reemerged in 1980. While the Nixon and Reagan campaigns aggressively pursued a “Southern strategy,” the 1976 campaign represented the last gasp of the old Democratic Party. Carter, a white governor from Georgia and a born-again Christian, walked a thin line to appease both his Southern base and northern liberals.

Figure 3 Vote Choice and Abortion Views

Notes: Each figure charts the average position taken on the ANES’ 4-point abortion scale by presidential vote choice. Higher values are more conservative. Respondents are given the following four choices: (1) abortion should never be forbidden; (2) abortion should be permitted if due to personal reasons, the woman would have difficulty caring for the child; (3) abortion should only be permitted if the life and health of the woman are in danger; and (4) abortion should never be permitted. The sample of African Americans who support Republican candidates is small, and results should be interpreted with caution (an N of 17, 5, and 7 in 1972, 1976, and 1980, respectively).

Elite Learning?

An existing strand of scholarship on public opinion argues that creative elites construct ideologies and diffuse these packages down to voters (Converse 1964). Consequently, one alternative explanation suggests that the issue bundles in figures 1–3 are the result of rank-and-file voters learning what goes with what from political elites. The previous section casts doubt on this explanation, because the linkages between policy attitudes predated the parties taking clear positions. However, this section further evaluates whether the linkages between abortion and other policy attitudes are unique to those who have learned what positions Democrats and Republicans support.

In 1976 and 1980, the ANES asked respondents to place the Democratic and Republican Party’s position on abortion and other policy issues on a left–right policy scale. Footnote 15 This allows separate analyses of respondents who knew the parties’ positions and those who did not. I classified “knowers” as those who perceived the Republican party’s policy stance to be to the right of the Democratic Party on abortion and the secondary issue. These voters are “knowers” in the sense that they have received or perceived partisan cues on both issues.

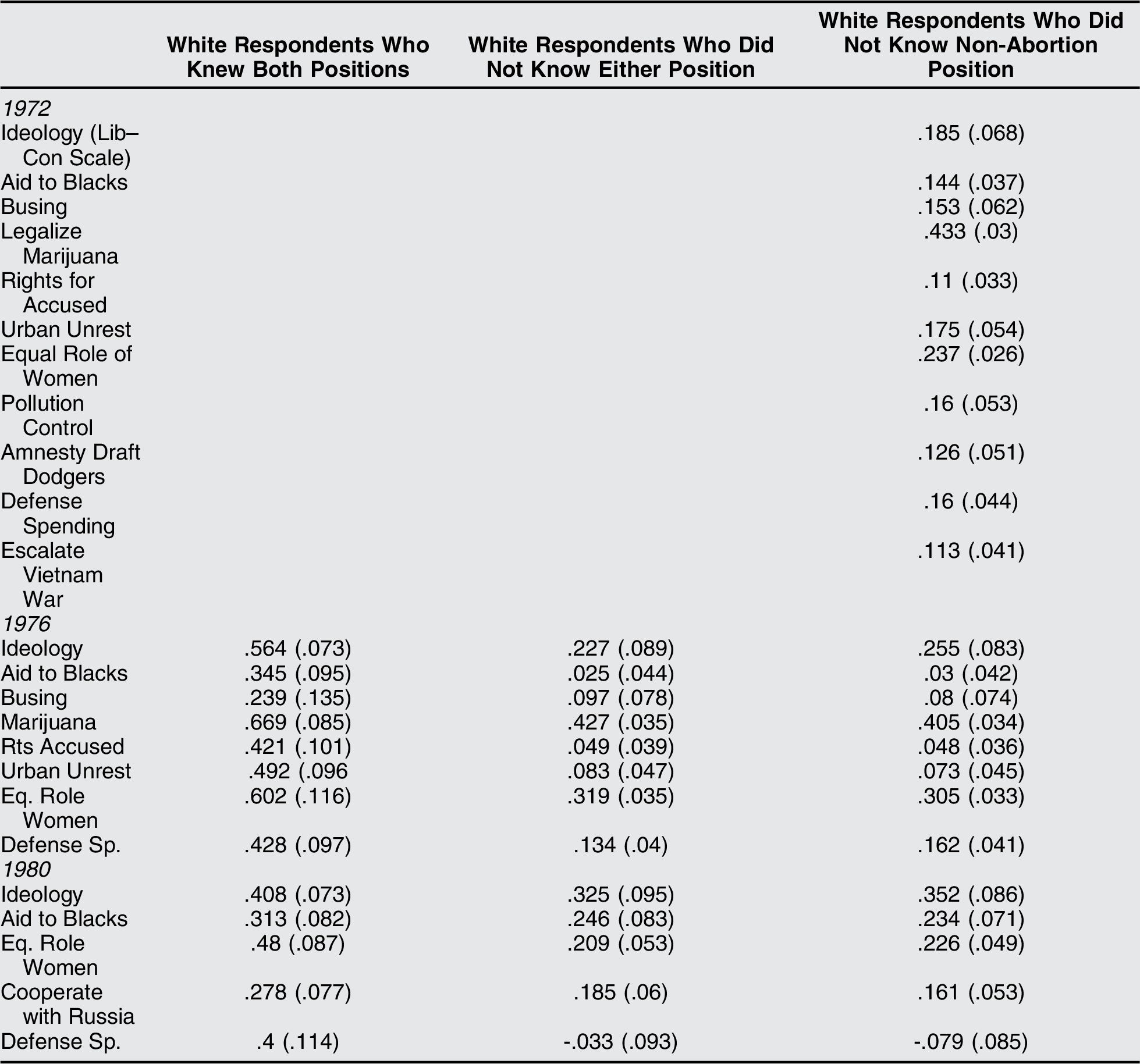

Elite-driven theories suggest that those who know the parties’ positions should consistently link issues together, whereas those who have not received partisan cues should not do so. However, table 1 shows that voters who “don’t know” the parties’ positions on either abortion or the secondary issue consistently express conservative attitudes on both abortion and the other issue (middle column). Although those who have learned where the parties stand on both issues (first column) show greater constraint, the fact that those who have not received partisan cues still bundle issues together suggests that elite learning cannot fully account for these linkages. Footnote 16

Table 1 White Respondents’ Knowledge of the Democratic Party’s Position on Abortion and a Secondary Issue

Note: Each cell represents the regression coefficient from regressing abortion attitudes on attitudes towards the policy listed down the left-hand column (same model as figure 1). I divided the sample between those that have and have not received partisan cues on both abortion and the secondary issues.

The last column of table 1 examines only respondents who do not know the parties’ position on the non-abortion question. This subsample includes respondents who do not know the parties’ relative position on busing or defense spending (for example), but may or may not perceive the parties to be different on abortion (the 1972 ANES did not ask respondents to place the parties’ positions on abortion). Footnote 17 A similar pattern persists.

However, an alternative argument can be marshaled. Although the parties lacked clear positions, both the pro- and antiabortion social movements, albeit small and ideologically heterogeneous, existed before 1972 (the section on interest groups discusses this in depth): therefore, the mass public may have adopted positions through learning from social movements.

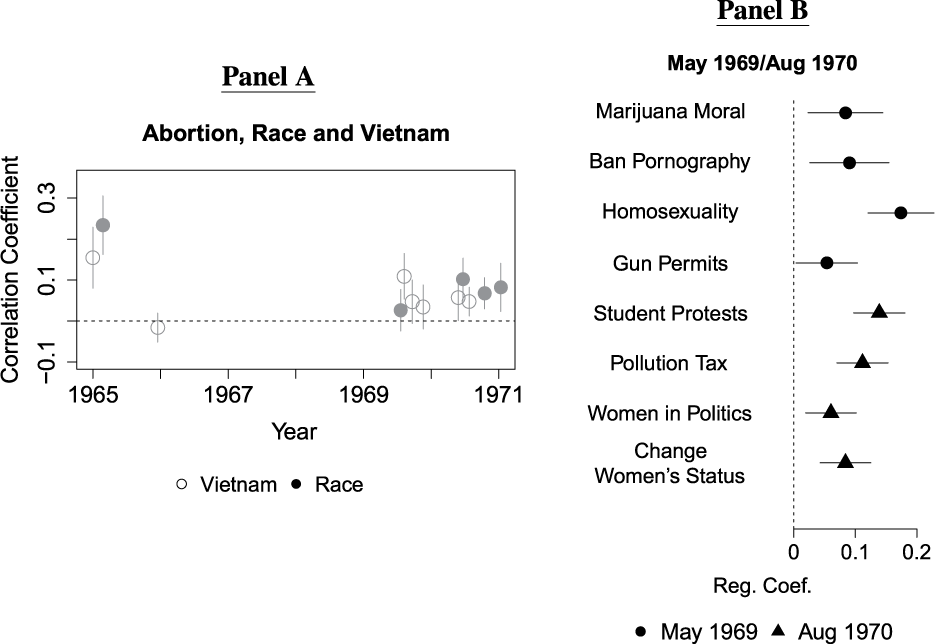

To account for this alternative explanation, panel A of figure 4 plots the correlation between (1) abortion attitudes and race and (2) abortion attitudes and military hawkishness before 1972. (I used historical survey data from Harris and Gallup polls, because the ANES lacked abortion-related questions before 1972.) Figure 4 shows that by 1965, conservative abortion views fit with conservative views on race and Vietnam. These data precede even the earliest rumblings of the abortion movement on the Left or Right.

Figure 4 A Longer Look

Notes: Each point in panel A represents the correlation between abortion attitudes and attitudes towards either Vietnam/defense spending or race. Positive coefficients mean that conservative abortion attitudes correlate with more conservative attitudes on Vietnam/race (refer to section 10 of the Supplementary Appendix for coding and data citations). Each point in panel B is the regression coefficient from regressing abortion attitudes on each variable listed down the left-hand column (same as table 1) using data from Harris surveys in May 1969 and August 1970. Each variable is 0/1. Positive values mean that those opposed to legalized abortion support the conservative position on each secondary variable.

To gain a broader understanding of early public opinion, panel B uses Harris survey data from May 1969 and August 1970, which to my knowledge, represent the earliest polling data that includes both abortion questions and these other policy issues. These data show that conservative abortion attitudes by 1969/1970 already aligned with conservative views on a range of other noneconomic issues. Although difficult to generate an exact timeline, these surveys coincide with the women’s movement becoming visibly associated with abortion rights for the first time (Freeman Reference Freeman1975, 84; Greenhouse and Siegel Reference Greenhouse and Siegel2012, 41). If the issue connections are going from activists to the mass level, the communication would have to be instantaneous and widespread. Alternatively, the pro-choice movement more likely gained success in liberal circles because it articulated a package of latent views that already fit together in the mass public.

Abortion and Economic Attitudes

Do attitudes about abortion align with those on economic issues? Economic liberals and economic conservatives hold statistically similar attitudes on abortion. Furthermore, those bundles that do exist are restricted to respondents who have learned the parties’ positions (refer to the section, “Economic Issues,” of the Supplementary Appendix). As I argue earlier, the fact that economic issues lack a substantive relationship with abortion attitudes makes it less costly for politicians to exploit the racial cleavage once race became activated in the 1960s (because economic issues do not act as a countervailing force). Consistent with top-down theories, elite actors seem to drive the eventual linkage of economic issues with abortion attitudes (see Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002).

Interest Groups

The coalition of antiabortion activists with other conservative groups inside the Republican Party matches a prominent constellation of attitudes first observed in the mass public. I argue that preexisting issue connections among ordinary voters enabled the eventual alignment of the pro-life movement, conservatism, and the Republican Party. This raises the question: What was the possibility for an alternative outcome?

Although it is impossible to explore the counterfactual, the earliest antiabortion activists were not members of the Christian Right, which first organized around abortion politics in 1979 (Balmer Reference Balmer2006; Schlozman Reference Schlozman2015). Instead, the pro-life movement was founded by an ideologically diverse group of activists, many of whom tried to connect their movement with other progressive causes and initially sought to ally themselves with the Democratic Party (Williams Reference Williams2016; Ziegler Reference Ziegler2015). However, building a pro-life movement in progressive circles meant trying to connect issues that did not already “go together” among ordinary people. For example, one pro-life leader believed that peace activists might serve as a core constituency. Footnote 18 Yet peace activists largely supported abortion rights (see figure 1), and such appeals lacked a broad audience.

Ideological Diversity in the Early Pro-Life Movement

Part of the pro-life movement’s initial liberal dynamic resulted from it being fairly small. Before Roe, national pro-life activism rested largely within the United States Catholic Conference and the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCC/NCCB). Footnote 19 Although heterogeneity exists throughout the broader Catholic Church, many leaders at the USCC/NCCB took liberal positions on social welfare programs and civil rights and vocally supported nuclear detente (National Review 1982; Williams Reference Williams2016). In the 1976 election, one Ford staffer noted that the “platform statement of the USCC reads like a laundry list for a Democratic Congress, except for abortion.” Footnote 20

Second, the Minnesota Citizens Concerned for Life (MCCL), one of the earliest and most successful state-level right-to-life groups, provided key leadership to the early national pro-life movement; this is partially because they had successfully organized at the state level. Most members of the Minnesota pro-life movement were otherwise liberals, and the MCCL was led by Marjory and Fred Mecklenburg, both political progressives who strongly believed in social welfare programs, women’s rights, and the use of contraception (Williams Reference Williams2016, 158). Footnote 21 Members of the MCCL argued, “How can you oppose killing in Vietnam while you support it at the abortionist’s clinic?” (Williams Reference Williams2016, 164).

Marjory Mecklenburg served as the first chair of the board of the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC), which today boasts that it is both the oldest and largest pro-life group. Other liberals joined her as well. Warren Schaller, the first executive director of the NRLC, favored the Equal Rights Amendment and supported social welfare programs to dissuade abortion for financial reasons (Ziegler Reference Ziegler2015, 187). Footnote 22

Mildred Jefferson, the first black woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School, served as the NRLC’s president in the mid-1970s. Jefferson, like other pro-life advocates, painted the pro-choice movement as an assault on African Americans and likened Roe to the Dred Scott case (qtd. in Klemesrud Reference Klemesrud1976; Williams Reference Williams2016, 170).

However, as the national pro-life movement expanded, and although more politically diverse than stereotypes might imply, it increasingly included more right-wing members (Granberg Reference Granberg1981). In democratic organizations such as the NRLC, this meant that new members supported more conservative leaders and pro-life pragmatists lost their influence or were forced to accommodate conservative forces. Mildred Jefferson felt pressured to move rightward to gain credibility among the group, Footnote 23 while Marjory Mecklenburg left the NRLC to start an antiabortion group that appealed to more diverse constituencies. Others, like Warren Schaller, left the organized abortion movement altogether (Ziegler Reference Ziegler2015, 217).

Rise of the Christian Right

Contrast early pro-life efforts to those of the Christian Right in the late 1970s. The very appeals made by Christian Right and New Right leaders—linking opposition to abortion to other conservative causes—matched many of the preexisting bundles of issues among the mass public.

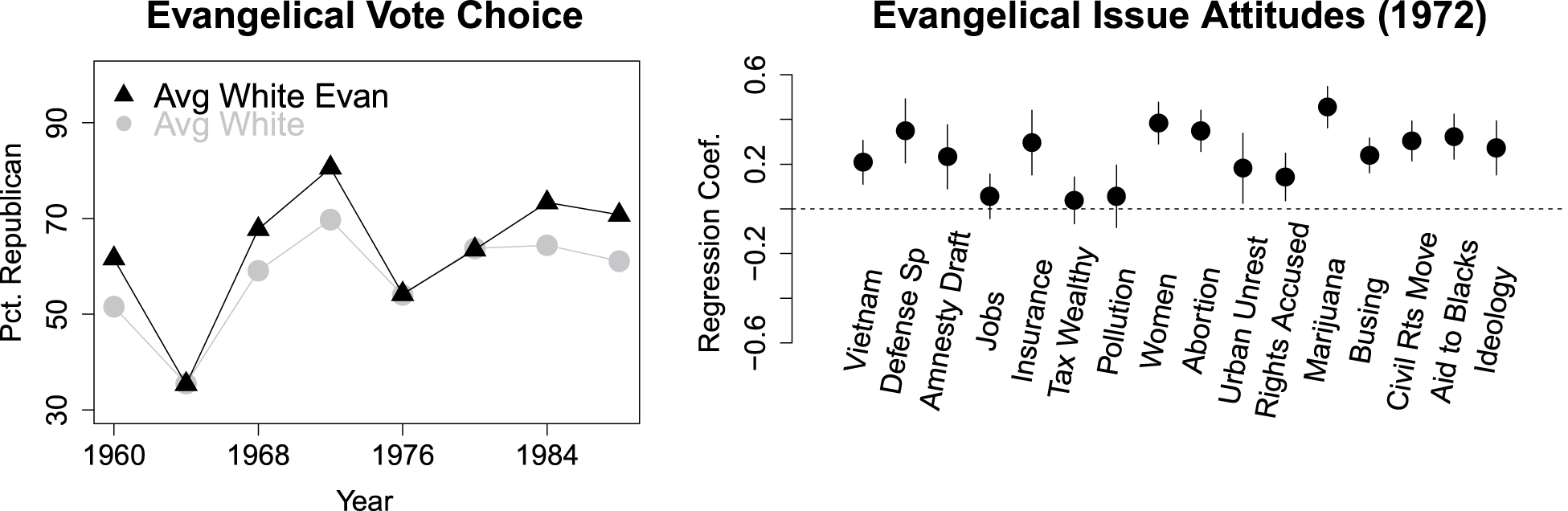

In fact, many evangelical leaders stayed quiet or even supported moderate to liberal abortion policies in the early 1970s. (Their initial reticence was partly due to evangelical leaders viewing abortion as an issue of importance for Catholics, an out-group.) This is despite the evangelical laity expressing as conservative positions on abortion as Catholics by the late 1960s (see figure 2). Furthermore, figure 5 shows that white evangelicals disproportionately voted for Republican candidates and otherwise held conservative political views decades before the Christian Right became politically activated in the late 1970s.

Figure 5 Evangelicals

Notes: Left-hand panel compares the percent of white evangelicals compared to all white voters who voted for the Republican presidential candidate (two-party vote share). Right-hand panel plots the regression coefficient from regressing each issue response (mean = 0; std = 1) on whether a respondent identifies as an evangelical (I limited the subsample to white respondents only). Positive values indicate that respondents who identify as evangelical take a more conservative position on the respective issue. Data are from the ANES.

In 1971, the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), the largest Protestant denomination and center of Protestant evangelism, passed a resolution that endorsed moderate abortion policies. Foy Valentine, the head of the SBC’s Christian Life Commission and advocate of the 1971 resolution, expressed moderate abortion positions and joined efforts that explicitly endorsed Roe and abortion rights. Footnote 24 Valentine had company. In February 1973, W. A. Criswell, a former SBC president and conservative religious leader, endorsed a woman’s right to choose (Schlozman Reference Schlozman2015, 103). Footnote 25 Adrian Rogers, whose election as the SBC’s president in 1979 marked the initial victory of a conservative insurgency within the Southern Baptist Convention, supported the SBC’s 1971 resolution. Footnote 26 And Billy Graham in 1970 reportedly remarked that abortion was permissible in some cases and that “nowhere in the Bible was it indicated that abortion is wrong.” Footnote 27

Other leaders simply stayed quiet. Jerry Falwell did not preach about abortion until 1978 (Schlozman Reference Schlozman2015, 103). Francis Schaeffer, an evangelical theologian whom many credit for raising the salience of the antiabortion movement among evangelical leaders, publicly opposed abortion only after his son prodded him to do so. Schaeffer initially argued he did not want to risk his reputation on a “Catholic issue” (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer2007, 266). Footnote 28

Furthermore, the Christian Right originally mobilized in national politics to protect the tax-exempt status of racially segregated Christian schools, not to fight against legalized abortion. Ed Dobson, a founding member of the Moral Majority, recalls, “I frankly do not remember abortion ever being mentioned as a reason why we ought to do something” (qtd. in Balmer Reference Balmer2006, 16). Indeed, the pivot of Christian Right leaders from school integration to abortion (which did not occur until the late 1970s) was facilitated by leaders who recognized that the white evangelical laity, on average, was conservative on both race and abortion (see Balmer Reference Balmer2006, 16).

This suggests that preexisting public opinion created an environment that enabled Christian Right leaders to enter the political arena and build a powerful social movement that reinforced issue connections already held by ordinary voters. And has been told from many perspectives, mid-level actors did play a crucial role in building the antiabortion movement. New Right political operatives recruited evangelical leaders such as Jerry Falwell to become politically active (Layman Reference Layman2001, 44). And evangelical leaders provided crucial resources and an organizational infrastructure to mobilize latent constituencies and raise issue salience (Layman Reference Layman2001; Schlozman Reference Schlozman2015; Wilcox Reference Wilcox1992; Ziegler Reference Ziegler2015, 201). Furthermore, Religious Right and New Right leaders built ecumenical alliances and raised awareness that Catholics were not the only ones who opposed abortion (Schlozman Reference Schlozman2015).

Pro-Life Activists Move to the Republican Party

What then of party positioning? Could interest groups have pushed the Democrats to the right of Republicans? Both the earliest antiabortion activists, as well as many leaders of the Christian Right, initially sought to align with the Democratic Party or were agnostic about which party aligned with their cause.

Some leaders at the USCC/NCCB, although careful to stay out of explicitly partisan politics, privately expressed disappointment that Democrats opposed their abortion stance. (Catholic leadership at the USCC/NCCB, like the Catholic laity, had been historically aligned with the Democratic Party.) Bishop Robert Lynch, then serving as the president of the National Committee for a Human Life Amendment, wrote his board of directors that “unfortunately… our strongest support for a human life amendment seems to almost innately rest among conservative and moderate Republicans [in Congress].” Footnote 29

Marjory Mecklenberg believed Democrats would support the pro-life movement because they had historically been an advocate for the oppressed, a label often assigned by pro-lifers to the fetus. Footnote 30 She worked hard to build the pro-life movement within the national Democratic Party and joined with leading Democratic politicians and operatives to support her cause. Footnote 31 In fact, Mecklenburg initially joined Sargent Shriver’s 1976 campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. Footnote 32 However, the Shriver campaign failed, and any ambiguity about Carter’s position or that the Democratic National Convention would support a pro-life plank dissipated. Footnote 33 Perhaps reluctantly, Mecklenberg noted, “Republicans have chosen to make abortion their issue” and without a Democratic alternative, she went to work for the Ford campaign. Footnote 34

Other liberals had similar experiences. Nellie Gray, who founded the March for Life, a pro-life rally that prominent politicians still attend today, was a self-identified feminist and was otherwise liberal. Alarmed at Roe v. Wade, she sought out Ted Kennedy and other liberal Democrats assuming they, like her, saw overturning Roe as an extension of the civil rights movement. One by one they turned Gray down before Senator Jim Buckley, a member of the Conservative Party from New York, agreed to help. One activist remembered that Gray’s “jaw dropped” because she could not believe that a Republican would help her cause (author interview with Connie Marshner, June 19, 2018). Footnote 35 When Ted Kennedy sought the Democratic nomination in 1980, Gray refused to endorse him because he supported a pro-choice plank, “regardless of his other votes [on non-abortion issues], no matter how good they are” (McCarthy Reference McCarthy1980).

Surprisingly, conservative activists also did not envy the GOP: “No one wanted the pro-life issue to be wedded to the Republican party,” Connie Marshner, a conservative “pro-family” activist remembers (author interview with Connie Marshner, June 19, 2018). Even leaders who later served as the face of the Religious Right only turned to Republicans after it became clear that Jimmy Carter was a liberal. Televangelist Pat Robertson, a modern-day fixture of the Christian Right, stated that he had “done everything this side of breaking FCC regulations” to get Carter, a born-gain Christian, in the White House in 1976 (Martin Reference Martin1996, 166). Footnote 36

The bottom line is that broader forces pushed pro-life activists to the Republican Party, even in instances where powerful leaders tried to achieve the alternative outcome.

Pro-Choice Feminism and the Democratic Party

Before 1973, only a few organizations undertook efforts to repeal abortion laws, and the movement’s small size meant that the pro-choice coalition crosscut ideological lines (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1991, 27). This is because some of the earliest and loudest proabortion voices advocated for abortion reform not as a woman’s right, but as a means for population control or to legally protect doctors (see Friedan Reference Friedan1976; Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1991). Indeed, at the time of Roe, Zero Population Growth (ZPG)—which supported abortion reform as a means of population control—was the only pro-choice group with a lobbying operation in Washington, DC (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1991, 63).

In the early 1970s, organized pro-choice activists had yet to emerge as national power players. Planned Parenthood did not endorse abortion repeal until 1969 and did not offer organizational support for the national effort until 1973 (Staggenborg 1991, 15). The National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (what is now NARAL) had just 651 individual members in January 1972. Footnote 37

And although the National Organization for Women (NOW; founded in 1966), endorsed repealing abortion restrictions in 1967, the topic caused internal divisions among the organization’s delegates. Footnote 38 First-wave feminists wanted to maintain organizational focus on economic equality, whereas younger members pushed the organization to endorse abortion repeal (Greenhouse and Siegel Reference Greenhouse and Siegel2012, 36). Some of the earliest feminists, including Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger, opposed legalized abortion (Critchlow Reference Critchlow1999, 135). Coupled with a lack of resources, the internal fracture precluded NOW from becoming a powerful abortion advocate before Roe (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1991, 20). In addition, pro-choice groups (as well as pro-life groups) struggled financially in their early years (Freeman Reference Freeman1975, 91).

The bottom line is that the pro-choice movement, particularly as a woman’s right movement, did not gain financial or organizational strength before Roe. However, just as preexisting opinion enabled the Christian Right to articulate pro-life views in a web of conservative causes, latent opinion facilitated framing pro-choice issues in a web of liberal causes. When Betty Friedan, then leader of the nascent National Organization for Women, pronounced that abortion access was a woman’s civil right (Greenhouse and Siegel Reference Greenhouse and Siegel2012, 38–39), she was expressing two ideas that already seemed to go together in the mind of the mass public (see figures 1 and 4).

Politicians

Like abortion activists, pro-life politicians came from both sides of the aisle, and many politicians changed their policy positions as abortion became increasingly salient (Karol Reference Karol2009). The resulting equilibrium among politicians—one in which pro-life views migrated to the Republican Party—mirrored the prevailing cleavage already found at the mass level. I argue that issue overlap in the mass public created an environment that made it easier for Republicans (Democrats) to pursue antiabortion (proabortion) voters, even when those positions ran contrary to interest groups’ demands.

Republicans

Nixon initially opposed abortion in the years leading up to the 1972 campaign in an effort to appeal to blue-collar Catholic voters, a constituency that had traditionally supported Democratic candidates (Greenhouse and Siegel Reference Greenhouse and Siegel2012, 157, 215, 291; Karol Reference Karol2009, 59–60). Footnote 39 Two intertwining factors motivated Nixon’s antiabortion stance during the 1972 campaign. First, Nixon injected abortion into the campaign because it divided Democrats. Second, Nixon and his aides realized that issue overlap between abortion, Vietnam, aid to minorities, and marijuana legalization meant that his opposing abortion rights would reinforce existing divides between Nixon and the leftward shifting Democratic party (Greenhouse and Siegel Reference Greenhouse and Siegel2012, 215–18). Footnote 40 The mass-level issue connections meant that, for Nixon to support abortion rights, he would have had to appeal to voters who already disliked him on other nonabortion social issues. Footnote 41 It was easier for Nixon to follow prevailing opinion. Footnote 42

However, Nixon ultimately dropped the abortion issue in the middle of the campaign. Public opinion data showed that race and Vietnam, not abortion, drove Catholics to Nixon (Greenhouse and Siegel Reference Greenhouse and Siegel2012, 292, n.122). Footnote 43 Catholics had already supported Nixon before he took his antiabortion stance, pollster Robert Teeter told Nixon’s chief of staff. Footnote 44 Without the benefit of attracting further Catholic support and to avoid offending other voters, Teeter advised Nixon that he should not discuss abortion. As a result of this poll, Nixon dropped the issue and privately expressed that the federal government should avoid setting abortion policy (Kotlowski Reference Kotlowski2001, 252).

Nixon’s experience underscores several key points. First, abortion conservatives had entered the Republican Party even without explicit appeals on the issue. Second, patterns among ordinary voters, not interest groups, created a set of opportunities and constraints that sparked Nixon’s and the Republicans’ shifting positions. Indeed, early pro-life activists wondered what compelled Nixon’s sudden fealty toward their issue. Footnote 45

Four years later Gerald Ford took a modestly conservative abortion position. As with Nixon, Ford’s position seemed more focused on dividing Democrats and winning conservative Catholic voters than a response to demands from conservative policy groups. Footnote 46 In fact, Ford, unwilling to move further right, rejected lobbying efforts by the Catholic Bishops and other pro-life leaders. Footnote 47 Many pro-life groups ultimately supported Ford, but only after Reagan, George Wallace (Democrat), and Ellen McCormack (Democrat) lost in the primaries.

By the 1980 election, Reagan had long opposed abortion beyond traumatic circumstances and opposed government funding for abortions (Williams Reference Williams2016, 80–84, 118). Whether voters, activists, or personal views motivated this view is unclear. Footnote 48 What is more certain is that the Christian Right played a prominent role in keeping the issue on Reagan’s radar. Yet even the Christian Right’s influence had limits; Reagan ultimately disappointed many abortion conservatives who believed he did not genuinely care or go far enough. Footnote 49

Democrats

Although feminists had entered the Democratic party in 1972, the party also contained large socially conservative constituencies, which precluded Democrats from sending clear signals on abortion through the 1970s (see Layman Reference Layman2001, chap. 4; Layman and Carsey Reference Layman and Carsey2002, 794; Young Reference Young2000).

The Democrats’ initial 1972 front-runner, Edmund Muskie, voiced skepticism toward abortion in early 1971, and Hubert Humphrey campaigned explicitly against abortion rights in 1972 (Williams Reference Williams2011, 520). Even George McGovern, who perhaps apocryphally started the campaign with a liberal position, had by May 1972 expressed opposition to abortion and said that states should decide their own policy. Footnote 50 In fact, McGovern floor whips successfully squashed efforts made by the Democratic National Committee to include pro-choice language in the Democratic platform, fearing it would “siphon off nation-wide votes” (Perlstein Reference Perlstein2008, 694). Footnote 51 Indeed, McGovern’s public indifference to abortion rights frustrated feminists (Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000, 37). Women leaders in the GOP actually pushed the Republican Platform committee to adopt a pro-choice position to lure feminists disaffected by McGovern’s betrayal (Williams Reference Williams2011, 523).

In the 1976 election, as on most issues, Carter purposefully adopted a moderate stance to position himself between his more conservative white Southern base and northern liberals who were needed for victory (author interview with Stuart Eizenstat, August 31, 2018). Throughout his presidency, Carter adopted a moderate position and opposed both constitutional efforts to overturn Roe and federal funding for abortion.

By the mid-1970s many pro-choice groups believed Ted Kennedy, the liberal (and Catholic) Democratic senator from Massachusetts, would carry their cause in presidential elections. This is despite Kennedy sending constituent mail opposing abortion until at least 1971 (Douthat Reference Douthat2009). What initiated Kennedy’s change of position?

In 1975, Kennedy led Senate opposition against a ban on federal funding for abortion. This perplexed national Catholic leadership, both because of Kennedy’s Catholic faith and their assumption that Massachusetts, the most Catholic state, would reject such rhetoric. Catholic leadership decided to confront Kennedy, but learned from Kennedy’s staff that the senator was “convinced” a majority of Massachusetts voters supported his view. Footnote 52 In a “Church-Kennedy” test on abortion, a member of the USCC writes, Kennedy would win because the electorate stood with him. Footnote 53

Apparently, Kennedy’s aggressively liberal stance on the abortion amendment also surprised both the National Organization for Women and NARAL founder Lawrence Lader. Footnote 54 Lader concluded that Kennedy’s move was politically calculated to win over liberal constituencies should he enter the 1976 primaries.

Kennedy ultimately did not run for president in 1976 and lost to Carter in the 1980 primary. Democrats did not nominate a firmly pro-choice candidate until 1984 and included compromise language in their national party platforms through the 1980s (Young Reference Young2000, 107).

Public Intellectuals

An influential argument advanced by Hans Noel (Reference Noel2013) contends that political thinkers at leading newspapers and magazines bundled issues together into ideologies decades before the party system reflected similar positions. However, evidence suggests that conservative intellectuals lagged behind voters and activists in linking antiabortion views with other tenets of conservatism.

For example, William F. Buckley, the founder of the National Review and arguably the most prominent conservative opinion leader of the mid-twentieth century, initially wrote harshly of the Catholic Church’s opposition to abortion. In April 1966 Buckley boldly wrote that labeling a fetus as a person with human rights “is a vision so utterly unapproachable as to suggest that the requirements of prudence and of charity intervene” (1966, 308). Readers responded harshly to Buckley’s seemingly proabortion position, and the National Review wrote few pieces on abortion over the next several years (at which point they switched to a fairly standard conservative position).

James J. Kilpatrick, a prominent conservative columnist who among other things opposed desegregation (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2010), emphatically expressed that the Catholic Church had no right to impose their abortion views on others (Kilpatrick Reference Kilpatrick1976).

Robert Bartley, editor of the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), adopted a compromise position in which he supported legalized abortion but believed it should not be publicly funded. Footnote 55 Indeed, the WSJ shifted from being pro-choice in the early 1970s to opposing abortion rights in the 1980s (Noel Reference Noel2013, 161–62).

And on the pro-choice side, many early intellectuals who supported decriminalizing abortion did so because it would legally protect doctors or as a means of population control, not to advance women’s rights (see Friedan Reference Friedan1976, 122; Williams Reference Williams2016, 109).

The bottom line is that the abortion attitudes of early thought leaders crosscut ideological lines before sorting into their now familiar pattern.

Conclusion

The alignment of white Evangelicals, the pro-life movement, and the Republican party contradicts what seemed to be true before the 1980 election: abortion was a Catholic concern, and Catholics were Democrats. Furthermore, in the 1970s, Democratic identifiers in the mass public were marginally more conservative on abortion than Republicans, and economic cleavages were effectively orthogonal to abortion attitudes. Therefore, existing scholarship emphasizes that antiabortion activists and party elites played the pivotal role in aligning the pro-life movement with the Republican Party.

I argue such views overstate the role of elite influence. Republican politicians were making choices in an environment where antiabortion attitudes overlapped with conservative policies already adopted by the Republican Party. For example, Nixon decided on his abortion stance in a political environment that was not defined solely by economic policies, and he did not view his coalition as limited to Republican identifiers. Rather, race, Vietnam, and marijuana legalization divided the electorate, and because he had positioned himself to the right on each of these issues, issue connections among voters made it easier to oppose abortion rights too. Similarly, although Catholics had historically supported Democrats, the turbulence of the 1960s meant that racially conservative and hawkish Catholics, who happened to be the most conservative Catholics on abortion, had already begun entering the Republican Party before any national politician made antiabortion appeals.

Likewise among activists, I argue that the very success of the Christian Right hinged partially on their ability to articulate what many voters already believed. The messages sent by Christian Right leaders were made in an environment where antiabortion appeals already fit into a web of conservative causes at the mass level.

Of course, if partisan divisions on Vietnam and race were themselves elite-led events, then party positioning would be about sequencing, rather than whether voters or elites are the first mover. In either scenario, however, the activation of race as a partisan cleavage created a set of contingencies that would be absent had the parties kept a lid on civil rights.

Finally, although this article focuses on abortion, the theory is generalizable. The political parties’ ability to position themselves on new issues may often be contingent on the latent views of constituencies already inside the party (see Schickler Reference Schickler2016). Numerous “single issues” gained political salience in the 1970s; to what extent did preexisting issue bundles narrow elites’ ability to position themselves on gun control or environmentalism? Can this theory help explain the Republican’s immigration position in the 2000s? Whereas existing scholarship emphasizes the ways mid-level actors and party elites matter for party position change, the argument here suggests top-down theories should be modified to more fully account for how and when public opinion matters too.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592719003840