Enthusiasm for autocrats presents something of a conundrum for political science. Ever since Linz’s (Reference Linz1975) seminal analysis of totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, scholars have seen the purposeful demobilization of the population through coercion and institutional manipulation as a defining characteristic of authoritarian regimes. Authoritarian legitimacy (to the extent that it is thought to exist at all) has been understood to be based either on protection from an alleged threat, or on a promise of effective government (Epstein Reference Epstein1984; Nathan Reference Nathan2003).Footnote 1 This view, however, oversimplifies the relationship between leaders and followers in contemporary autocracies. It cannot, for example, provide a satisfying account of the fact that significant portions of societies, in countries from Russia to China, Hungary to Turkey to Venezuela, enthusiastically support leaders who stifle freedom of speech, throttle civil society, and monopolize the political playing field—or worse. In reality, contemporary authoritarians often rely on active mobilization that involves and actively engages citizens who, in turn, do not merely consent to support the leader, but invest in that leadership feelings of trust, pride, and hope.

In this article, we unpack the politics of authoritarian engagement in one archetypical contemporary authoritarian regime, Russia. To do so, we focus on the role of emotions. Once quite marginal to the worldview of most political scientists, the importance of emotions is now widely recognized (Groenendyk Reference Groenendyk2011). In American politics, scholars have explored numerous approaches to understanding the “effect of affect” on attitudes and behavior (Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000). Emotions have been shown to affect political agenda-setting by shifting individuals’ attention and focus (Clore and Gasper Reference Clore, Gasper, Frijda, Manstead and Bem2000), and to create linkages between politically irrelevant events, such as sports scores and political behavior (Healy, Malhotra, and Mo Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010). In international relations, researchers have studied how emotions affect decision-making, terrorism, and the interactions between states (Mercer Reference Mercer2010). Finally, in comparative politics, emotions are increasingly recognized as central to phenomena ranging from violence and ethnic conflict (Petersen Reference Petersen2002) to protest cascades (Pearlman Reference Pearlman2013).

Nevertheless, the role of emotions in providing support for authoritarian regimes is almost completely neglected in contemporary political science. Most work on autocracy has focused either on the economics of how autocrats maintain control (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Treisman Reference Treisman2011), on the role of institutions (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008) and dominant parties (Reuter Reference Reuter2017), or on coercion (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010) and manipulation (Schedler Reference Schedler2006). In the few modern studies looking at emotions and authoritarianism, the focus is either on the opposition (Pearlman Reference Pearlman2013) or on negative emotions such as fear and anger (Bishara Reference Bishara2015; Young Reference Young2019). We contribute to this research, but, crucially, change the focus from negative emotions and the opposition to unpacking the role of positive emotions in generating support for authoritarian leaders.

To illustrate the importance of positive emotions, we turn to one of the most remarkable surges in the political fortunes of an autocrat in recent years. Taking advantage of a unique panel survey conducted immediately before and after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, we are able to unpack not just Vladimir Putin’s well-known dramatic rise in popularity (Hale Reference Hale2018; Rogov Reference Rogov2016), but also to tell—and attempt to explain—the as yet undocumented story of the broader transformation of how Russians felt about their leader, and how they evaluated conditions in the country.

What we see is not just an increase in support, but a powerful strengthening of emotional connection among previously skeptical citizens. Putin went from being widely popular but largely unloved, to being a source of pride and hope and a locus of trust. As we show, the change was not just an isolated, individualized phenomenon. It was also a collective process, in which people became more emotionally invested at the same time as they engaged more deeply with their fellow citizens, with the media, and with politics more broadly. Change was most marked amongst those who became most involved in the collective experience of the Crimean annexation—particularly consuming and discussing news. This highlights, we argue, that the emotional wave came not just from above, but also from Russians interacting with one another and with the shared experience of politics at the time. Moreover, as we demonstrate, this surge of emotional engagement did much more than boost the fortunes of the regime: it transformed the way Russians saw their lives, their futures, and even their past, creating a wave of positivity.

The argument is not that Putin’s post-Crimea wave is typical of how support for authoritarian leaders is maintained from day to day. Nevertheless, our findings do illustrate a common and neglected role for emotions in authoritarian politics. After all, while the Crimean annexation and the war in Ukraine were specific events, the phenomenon of authoritarian regimes mobilizing populations against foreign or domestic enemies is very common. Consequently, while our case may be a particularly vivid example, the general analysis is relevant to autocracies well beyond Russia.

Finally, this article should also be of interest to scholars in political science and sociology interested in “rally around the flag” events. Our analysis expands the existing literature on rallies in two important ways. First, we expand the empirical reference of the rally literature, which has focused almost exclusively on the United States (Feinstein Reference Feinstein2016; Kriner and Schwartz Reference Kriner and Schwartz2009; MacKuen Reference MacKuen1983; McLeod et al. Reference McLeod, Eveland and Signorielli1994; Mueller Reference Mueller1973; Parker Reference Parker1995) and other democracies (Amuzegar Reference Amuzegar1997; Lai and Reiter Reference Lai and Reiter2005) to an authoritarian regime. This is an important step because, as we argue, rallies have different features depending on regime type. Most notably, rally events in democratic regimes typically feature a temporary suspension of intra-elite competition (Brody and Shapiro Reference Brody and Shapiro1989; Brody Reference Brody1991) and the establishment of an also temporary pro-government consensus in the media (Baum and Groeling Reference Baum and Groeling2008). In authoritarian regimes, by contrast, elite consensus and a cheerleading media are not transitory anomalies, but are part of the normal order of business. Consequently, what marks rally periods in authoritarian regimes out from normal politics is less intra-elite politics and the flow of propaganda from above (though these may still play a role), and more the distinctive way in which citizens interact with that propaganda in extraordinary moments. As a result, although rallies in both systems share a large role for popular sentiment, the way sentiment interacts with elite politics is different.

Second, we expand the theoretical scope of the rally literature, shifting the focus to the role of affect. Political scientists looking at rally events have focused on the approval rating of incumbents, which is an important but narrow part of what rallies are about. Scholars in sociology have tended to look more broadly, unpacking effects on identities and affect (Bonikowski and DiMaggio Reference Bonikowski and DiMaggio2016; Citrin, Wong, and Duff Reference Citrin, Wong, Duff, Ashmore and Jussim2001; Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006). Here we expand this path further, looking at how rallies change both identities and affect, demonstrating in the process that, in this case at least, the political effect of the rally has less to do with changing citizens’ sense of identity or patriotic affiliation, than with changes in positive emotions such as pride, hope, and trust.

Emotions, Politics, and Authoritarianism

While there has been some important work on emotions and their role in the politics of protest and of challenging state leaders (Pearlman Reference Pearlman2013; Slater Reference Slater2009), the literature on how authoritarian rule is maintained has been overwhelmingly top-down and materialist in flavor. The key focus has been on institutions and the incentives they create (Geddes Reference Geddes1999). This literature is extensive and wide-ranging, including important work on the role of elections (Lust-Okar Reference Lust-Okar2005), legislatures (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008), and dominant parties (Reuter Reference Reuter2017). Nevertheless, attention is starting to shift away from institutions and elites and towards the interaction between those elites and society at large—although even here the emphasis remains largely materialist, focusing on economic sentiment (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Treisman Reference Treisman2011) or social class (Roberts and Arce Reference Roberts and Arce1998). In Russia specifically, economic factors have figured strongly in explanations of mass support (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017; White and McAllister Reference White and McAllister2008).

However, recent research on authoritarianism has started to move away from a purely materialist account. In path-breaking work in Zimbabwe, Young (Reference Young2019) demonstrates the importance of fear and anger in either inhibiting or encouraging political activity on the part of opposition supporters. Fear is also the primary emotion underlying the substantial literature on preference falsification (Kuran Reference Kuran1997). Pearlman’s research goes further, looking at the contrasting role of fear and “dispiriting emotions” on the one hand and anger and “emboldening emotions” on the other in the Arab uprisings of 2011 (Pearlman Reference Pearlman2013). Russian scholars, writing in Russian, have noted the role of offense and indignation (Baunov Reference Baunov2014), of “ressentiment” (Medvedev Reference Medvedev2014), and of pride (Sheinis Reference Sheinis2016).

Positive emotions, however, are largely absent from analyses of autocracies. In non-authoritarian contexts, researchers have begun to build a considerable literature on the interaction of positive and negative emotions. Lecheler et al. (Reference Lecheler and de Vreese2011), for example, show that enthusiasm, as well as anger, mediate the effect of news frames, and Panagopoulos (Reference Panagopoulos2010) shows how pride and shame work differently to influence electoral turnout. Moreover, appeals to positive emotions like hope and enthusiasm seem to work in similar ways to appeals to negative emotions like fear and anxiety (Brader Reference Brader2006). Following in this vein, there is no reason why positive emotions like pride, hope, and trust should not also play a role in generating support for authoritarian regimes.

How Emotions Build and What They Change

In the rest of this paper, we illustrate the role positive emotions can play in building engagement with and support for an authoritarian ruler. We begin by leveraging the Crimean experience to make two arguments. The first argument, which builds primarily upon literature in political sociology, is that collective experience and rising emotional attachment go hand in hand. Citizens who engage more with politics as a collective experience are also more likely to experience growing emotional attachment to the regime. The second argument, which draws on political and social psychology, suggests that growing positive emotions are likely to have wide-ranging effects on issues quite unrelated to the actual political events of the time.

Our first proposition is that the development of strengthened emotional connections is related to a person’s participation in the broader society’s experience of politics. Those who participate most in the collective experience of politics are also those who develop the strongest sense of emotional engagement. Participation in the experience goes hand in hand with building emotional attachment.

For most political scientists who study emotion, the dominant approach is to study how emotions condition or motivate behavior, whether voting, activism or simply opinion (Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011; Valentino, Gregorowicz, and Groenendyk Reference Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk2008; Groenendyk Reference Groenendyk2011; Brader Reference Brader2005). However, while we clearly think emotions have consequences (as we detail later), our argument suggests that the relationship between the “stimulus” of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and individuals’ emotional “response” is itself related reciprocally to an individual’s propensity to consume more political information (particularly on television) and to discuss politics more frequently with friends and family. An interactive relationship between behavior and emotion is consistent with much recent research on political communication, which has shown the impact of television news on preferences for American presidential candidates to be mediated by emotion (Namkoong. Fung, and Scheufele Reference Namkoong, Fung and Scheufele2012), as well as work in sociology that tends to see emotional responses as being produced during and by the collective political experience itself—politics being inherently a group activity (Nelson Reference Nelson1996; Lawler Reference Lawler, Burke, Owens, Serpe and Thoits2003; Berezin Reference Berezin2002).

In our story, the collective experience of politics comes in part through people discussing politics with their friends, family, co-workers, and neighbors. Existing research shows that discussion is critically related to political participation (Vaccari, Chadwick, and O’Loughlin Reference Vaccari, Chadwick and O’Loughlin2015; Kwak et al. Reference Kwak, Williams, Wang and Lee2005). Here we show that discussion is also related to emotion—people who have larger increases in political discussion are also those who experience more growth in emotional engagement.

Another key part of the story is consumption of politics on television. In a seminal study of big “media events,” Dayan and Katz describe the intense media focus on a single issue as having the capacity to “integrate societies in a collective heartbeat and evoke a renewal of loyalty to the society and its legitimate authority” (Dayan and Katz Reference Dayan and Elihu1992, 9-10; emphasis original), “riveting them not just to programs in general, but to the very same broadcast; transporting them not just elsewhere, but to ‘the center’” (Katz and Dayan Reference Katz and Dayan1985). The result is an interaction of the “automatic” physiological emotions and emotions produced by social context, which influences that psychological response by creating perceptions of others’ emotional states (Gross Reference Gross2002). And as we will document, Russian television went to great lengths to transform the Crimean annexation into such a moment, and the more people engaged with Crimea as a media event, the more emotionally engaged they became.

Second, we argue that growing emotional attachment is likely to have significant and wide-ranging implications for how those who experience the rallying moment see a broad range of elements of the world around them. Psychologists have long known that emotional states can affect judgments on issues far from the emotional state in question (Frijda, Manstead, and Bem Reference Frijda, Manstead and Bem2000). Political scientists have shown that extraneous events that affect people’s sense of well-being can affect voting behavior (Healy, Malhotra, and Mo Reference Healy, Malhotra and Mo2010). Similarly, work in social psychology has shown that participation in or even proximity to collective experiences can lead to increased positive affect and positive social beliefs (Lumsden, Miles, and Macrae Reference Lumsden, Miles and Macrae2014; Páez et al. Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015; Cialdini et al. Reference Cialdini, Borden, Thorne, Walker, Freeman and Sloan1976). Studies have also found effects on “generalized prosocial” emotions, i.e., positive emotions directed not only towards those involved in the shared moment, but to society more broadly (Reddish, Bulbulia, and Fischer Reference Reddish, Bulbulia and Fischer2014).

Taken together, these different streams suggest that we should see quite broad effects of increased emotional engagement of the kind we describe here. In fact, as we will see, the sense of emotional connection experienced by many Russians after Crimea indeed had far-reaching implications for how they perceived the world around them, the future, and even their own past.

The Crimea Moment

The empirical context for our analysis is the extraordinary increase in support for Russia’s President Putin that took place between March and June 2014 (and was sustained for four years, until the summer of 2018). The key event associated with the rise in support for Putin was the Euro-Maidan revolution in Ukraine that played out in late February and March 2014. Within a week of the revolution, Crimea came under the control of pro-Russian forces. On March 18, Putin signed a law incorporating Crimea and Sevastopol into the Russian Federation. At the same time, anti-Maidan forces, also backed by unidentified troops, had taken control of the east Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, with skirmishes in some smaller cities, too.

Prior to the annexation of Crimea, Putin had been in a long ratings “funk.” The Levada Center tracking poll showed his approval at 79% in December 2010, but support steadily fell, and by 2013 it was stuck in the low 60s. Most explanations of Putin’s troubles came down to a combination of economic malaise and negative reaction to Putin’s decision to switch jobs twice with premier-turned-president-turned-premier Dmitry Medvedev (Belanovsky et al. Reference Belanovsky, Dmitriev, Misikhina and Omelchuk2011). Putin’s declining ratings also reflected the anxiety of an economically successful urban class that feared a conservative turn under Putin (Greene Reference Greene2014), and the worries of those who felt left behind by modernization and wanted a more “pro-social” policy (Gel’man Reference Gel’man2015).

After Crimea, however, Putin’s ratings were transformed. In the midst of a blitz of media coverage of the crisis warning of the return of fascism and of threats to the safety of Russian-speakers in Ukraine, approval of the president shot up to 80% in March 2014 and remained above 80% until February 2018. It is not possible to know exactly why Crimea resonated with the Russian public, while, for example, the successful Sochi Olympics did not. Crimea, of course, has long been present as an object of desire in certain sectors of the Russian political discourse, and previous generations of Russian politicians did use it to mobilize support (Colton Reference Colton1999; Zevelev Reference Zevelev1996). It thus might have been primed for emotional resonance in a way that other events were not; the annexation itself also came as a surprise, which may have amplified the emotional response. Or perhaps winning medals and winning territory simply strike different chords.

Television certainly played a key part in this process. The annexation of Crimea and the ensuing emergence of conflict in Donbas was accompanied by a massive outpouring of coverage on Russian television. The content of the coverage featured a dominant “national irredentist” frame that, while emphasizing language over ethnicity to define the “in-group,” nonetheless sought to draw clear boundaries with Ukrainians (and Europeans more generally) as the “out-group” (Teper Reference Teper2015). As presented on Russia’s state-dominated television, this was not a land-grab, but rather the historic return of lost territory, couched in the language of justice and clothed in religious symbolism (Medvedev Reference Medvedev2014). The annexation itself was carried out by mysterious but heroic “little green men” and “polite people” and was the subject of breathless television coverage and documentaries, and rallies and marches in support of Putin and opposition to the Western-backed “fascist junta” in Kyiv. Citizens were invited to participate in countersanctions leveled against imports of Western foods, identifying and turning in contraband as individuals, or under the aegis of various groups, including the Cossacks. Those who preferred to participate from the sofa could witness the televised destruction of thousands of tons of European cheese, poultry, and other goods on the nightly news. The result was the transformation not just of Putin’s popularity, but of many Russians’ emotional orientation towards their leadership.

Many independent media in Russia—often lacking the resources to cover the conflict directly—either fell into line with the mainstream narrative, or else avoided the topic. Even the opposition-minded Russian online television channel Dozhd found itself banned in Ukraine for coverage that authorities in Kyiv felt resonated too closely with that found on Russian state TV (Korrespondent 2017). A similar dynamic affected generally opposition political leaders; some, such as then-Duma Deputy Il’ia Ponomarev and the late Boris Nemtsov, spoke out against the annexation openly; many others, including Alexei Navalny, refused to do so, and disagreements over Crimea contributed to splits within the opposition (BBC 2014).

This hawkish coverage both increased Russian media consumers’ support for the conflict and Russia’s role in it (Ray and Esipova Reference Ray and Esipova2014) and drew more people into engagement with politics and state media. One of our interview respondents—a 44-year-old female receptionist from Yaroslavl—reported an experience that was quite common at the time: “I never used to watch the news very much. But starting in Reference Ray and Esipova2014, I just got hooked on the news, I started watching it constantly. It was Crimea, of course!” Our respondent was not alone in this. According to TV ratings data tracked by the market research agency TNS Russia, viewership of the evening news on the major channels (all of which are controlled by the state) accounted for around 5.9% of total television viewership in 2013. In February Reference Sobolev2014 the month of both the Sochi Olympics and the culmination of the revolution in Ukraine—this figure rose to 6.5% and in March, the month of the Crimea events themselves, to 8.3%. This is a more than 40% increase, and viewing figures remained at that elevated level through the spring and summer, as war erupted in Donbas (Sobolev Reference Sobolev2014). Moreover, experimental research by Stoycheff and Nisbet demonstrated the power of prompts modeled on those used by Russian state TV in shaping respondents’ views of Crimea, independent of any prior knowledge of the event (Stoycheff and Nisbet Reference Stoycheff and Nisbet2016).

Not only did Russian TV news capture more of viewers’ attention, but there was also more of it. News broadcasts previously lasting 20–30 minutes were extended to a full hour, and the usual post-news entertainment was frequently replaced with more news (Borodina Reference Borodina2014); the Sunday news roundups were extended from one hour to two. According to Borodina, in February–April Reference Borodina2014, the two most popular evening news broadcasts—Vesti and Vremia—averaged ten segments of 7–10 minutes each per evening dedicated to Ukraine.

All this coverage was hugely influential. According to a poll conducted by the Levada Center in March Reference Volkov and Goncharov2014, some 51% of respondents reported getting their news and information from only one source—and that source was overwhelmingly television (Volkov and Goncharov Reference Volkov and Goncharov2014); among the further 20% who reported using a second source of information, that source was most frequently “friends and relatives” who, of course, would primarily have gotten their news from the television. Moreover, the impact of the TV narrative and framing was not limited to that medium. Research has shown that TV messaging shaped the way the Ukraine story developed on the Internet as well, primarily by making the “Fascism” and anti-American tropes inescapable (Cottiero et al. Reference Cottiero, Kucharski, Olimpieva and Orttung2015). The overall effect, then, was that the “Crimea Syndrome,” as the Russian political observer Kirill Rogov called it, spread epidemically throughout the population, infecting even those who might have thought of themselves as relatively well inoculated against the ills of Russian state television (Rogov Reference Rogov2015). As we will see, the effects of engaging with this media experience and with other citizens were powerful and wide-ranging.

Ours is not the first paper to look at the rally for President Putin around the annexation of Crimea. In a cross-sectional context, Hale (Reference Hale2018) argues that patriotism is key to approval, though “counter-intuitively” the effects of Crimea appeared to be largest amongst those who watch the least television news. With our panel methodology (interviewing the same respondents before and after the annexation, we are able to go further and show that the effect is in fact largest amongst those who may previously have not paid much attention to politics but who increase most their engagement with politics on television and within their social circles. Moreover, we show that while patriotism appears to lead to increased approval, this effect largely disappears when we take into account emotions, and patriotism cannot explain the broader effects that we see. Our research also provides empirical confirmation of Kirill Rogov’s insightful claim that it is not propaganda per se that matters, but the perception of a united society acting together that made the rally so deep and so durable (Rogov Reference Rogov2016).

Data

We illustrate our arguments using data from a panel survey we conducted in October 2013 and July 2014, five months before and four months after the annexation of Crimea, respectively. About 1,200 respondents completed the full questionnaire in round 1, and 715 in round 2. There is no evidence that panel attrition introduced any substantive differences in the sample between rounds. In fact, mean approval in round 1 amongst those who did not respond in round 2 (2.5) was statistically indistinguishable from those who did (2.4). All results presented here hold when taking panel attrition into account.Footnote 2

Our survey sample was designed to focus on Russia’s urban classes, a group hotly contested both politically and analytically. To accomplish this, we invited residents of cities with at least 1 million people, who were between the ages of 16 and 65, had at least some university education, and had access to the Internet; invitations were also stratified by age and gender to reflect Internet penetration in Russia. Additionally, respondents were screened for income, and only those reporting that they could at least afford basic necessities such as food were included.Footnote 3

The selection of this sample was not nationally representative, but rather was intended to capture a higher proportion of opposition supporters than one would find in the population at large. This allows us better to see different dynamics across supporters and opponents of the Kremlin. Of course, the cost of such a sampling strategy is that it necessarily limits what we can say about levels of support across the population and limits to some degree what we can say about the effects of factors such as education (and, to a limited extent, income), whose variation is truncated in our sample. Nevertheless, since our primary interest here is not in making point estimates, but instead in demonstrating the role of emotions and political engagement, this is a trade-off worth making.Footnote 4

Moreover, the dynamics of presidential approval within our sample are fascinating and illustrate perhaps even more starkly than the national data the degree of rallying round the leader that took place following the annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the war in eastern Ukraine. At the national level, the Levada Center found 85% of respondents approving of the job Vladimir Putin was doing as president, up from 64% in October 2013. In our sample, in October 2013 only 53% of respondents approved of the job Putin was doing. By July 2014, this figure had soared to 80%, almost the same as in the national polls.

The transformation of emotional orientation was even more dramatic than the simple increase in support for Putin. We measured positive emotional engagement in three ways: Pride, hope, and trust. Respondents were asked on a seven-point scale the extent to which they felt each of these emotions when they thought of Russia’s political leadership. While Putin was popular before Crimea, he did not inspire much pride (only 15% expressed any feelings of pride), nor hope (22%), nor trust (25%). After Crimea, it was a different story—now 37% expressed feelings of pride, 44% hope, and 46% trust.

This was a huge change. While it is difficult to compare across differently worded questions and different scales in quite different contexts, a comparison with 9/11 in the United States suggests something of the scale. The twenty-seven-point increase in approval for Putin is only six points less than the increase in approval for George W. Bush after his speech on September 11, 2001 (Schubert, Stewart, and Curran Reference Schubert, Stewart and Curran2002, 572). Moreover, in the 9/11 case, emotions changed much less than approval, but here the changes in approval and emotions are of similar magnitude.Footnote 5

Hypotheses and Measurement

To recap our theoretical arguments, we advance two basic propositions: First, that the increase in emotional attachment to the leadership was related to increased participation in the collective experience of politics at the time; and second, that this kind of positive emotional engagement improves individuals’ sense of their own well-being, thus altering perceptions of a broad range of unrelated material factors that might affect political support. We take these propositions in turn.

Proposition 1: Participation & Emotional Engagement

We test this argument in two equivalent ways: using an individual-level fixed-effects design, and a difference-in-difference design, both of which allow only factors that change from one round to the next to explain changes in the dependent variable. The test is simple and intuitive: if we expect that increased engagement in the politics of the moment boosted emotional engagement, then those who increase their political engagement more should experience more change in emotional engagement. Due to space constraints, only the fixed-effects model is presented and discussed here, while the results for the difference-in-difference analysis, which are substantively the same, are presented in table A1 in the online appendix.

The dependent variable in this analysis is positive emotional engagement, measured using an index of pride, hope, and trust. Respondents were asked on a seven-point scale the extent to which they felt each of these emotions when they thought about Russia’s leaders. We averaged these three responses to a single seven-point scale. Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of the scale is .93. In October 2013, the mean score on our scale was 3.1; by June 2014 it had risen to 4.1.Footnote 6 The results are identical if we run the models on each emotion separately.

We measure participation in the collective experience of Crimea in three ways. First, and most straightforwardly, we looked at the change in the extent to which citizens discuss politics with others. We asked respondents how frequently they discussed politics in five different contexts—with family members, neighbors, colleagues, friends, and on social media. We created a simple additive index to generate a single measure of political discussion and expect increasing political discussion to be associated with increasing political engagement. Like interest in politics, there was a significant increase in the frequency with which our respondents talked politics in their various circles. Before Crimea, some 47% of respondents discussed politics at least once a week on average across these different contexts. After Crimea, that number had increased to 58%.

Our second measure is the extent of change in the consumption of state television news. We asked respondents how often they watch state television for news (never, rarely, a few times a month, a few times a week, daily). Following the television ratings data and the example of our interviewee in Yaroslavl mentioned earlier, we interpret increased attention to state television news in this period as becoming involved in the collective moment.

Scholars of media and mass communications have long understood the consumption of television—and broadcast media more generally—to be a collective, as well as an individual-level phenomenon. Messages received on the evening news, or scenes from popular sit-coms, resonate at lunch tables and in business meetings, in churches and social groups (Silverstone Reference Silverstone1994).Footnote 7 As such, viewers consume television because other people are doing it and because they want others to know they are doing it, too, in a manner akin to Chwe’s (Reference Chwe2013) conceptualization of “common knowledge”—the awareness of what everyone knows that everyone knows that everyone knows. A similar dynamic is at work in the role that television (and other media) plays in classical explanations of the construction of nationalism (Anderson Reference Anderson2006; Billig Reference Billig1995). While we are unable in our survey to capture the increasing intensity of the experience of watching state television, our measure captures well the change in the extent to which any given individual chooses to subject themselves to the emotion-laden experience described by the media scholarship referenced above. Some 27% of respondents increased their state television news consumption, though many also selected out, with 16% of respondents reducing their consumption. Consequently, we would expect that people who start watching more state television are participating more in the collective experience around the Crimean annexation and so should show greater emotional engagement.

Finally, we also measure participation in the Crimean moment by looking at expressed interest in politics. There was a very substantial increase in interest in politics between the two rounds, as the intense media campaign drew more and more attention from previously disinterested citizens. In our survey, some 66% of respondents reported substantial interest in politics in round 1, but after Crimea this number had gone up to 82%. Consequently, we look at the effects of increasing interest in politics on levels of positive emotional engagement, expecting increasing interest to be associated with increasing positive emotions.

In all of our analyses we employ a range of commonly used controls. Following Hale (Reference Hale2018), we think that attention to alternative narratives is likely to matter. We measure this with a binary variable indicating whether respondents used Live Journal—a blogging site popular amongst critical journalists, scholars and citizens—for news and information about politics. We also include a range of socio-economic variables that have been shown to matter in Russia, specifically public sector/private sector employment, wealth, education, sex, age cohort, and perceptions of personal economic experiences in the last year (Colton and Hale Reference Colton and Hale2009).Footnote 8 Perceptions of personal economic experiences, like interest in politics, are measured on an ordinal scale—better, same, worse.

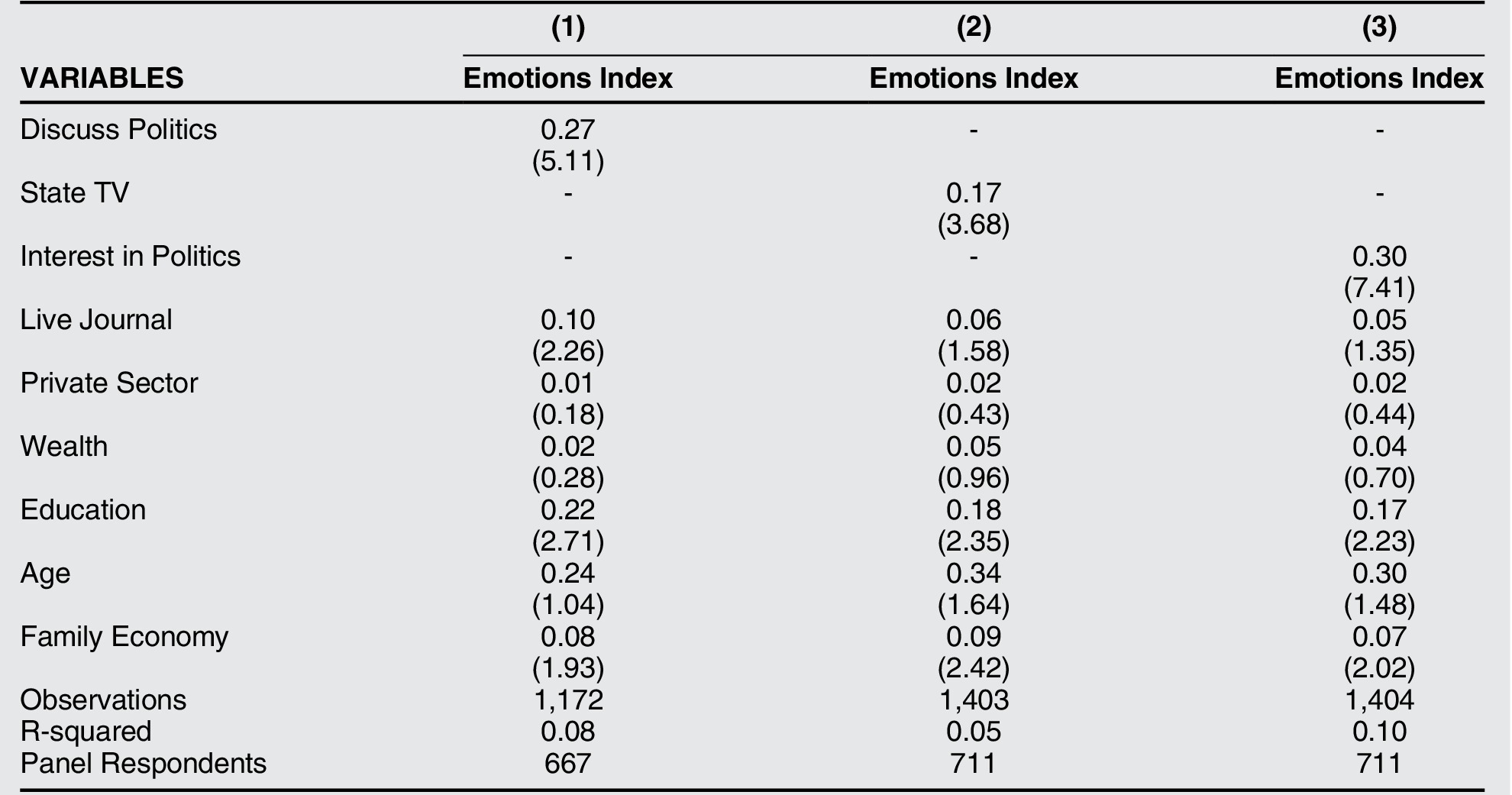

Table 1 presents the results of the individual-level fixed effects models using OLS regression with standardized beta coefficients. In models 1 to 3, we enter discussion, state-owned television-watching, and political interest separately, as they are all intended as different measures of the same phenomenon—participation in the Crimean moment. As the table shows, each of these is substantively and significantly associated with changes in the emotions index; a standard deviation change on our discussion scale is associated with a .27 standard deviation increase in the emotions index. The same change on the television scale is associated with a .17 standard deviation increase in emotions, and on the interest in politics scale, a .30 standard deviation increase. Footnote 9

Table 1 Political engagement and emotions

OLS regressions with individual fixed effects. Beta Coefficients t-statistics in parentheses.

Economics, the factor most focused on in the existing literature, still matters, though the relationship with emotions is much smaller than for television, interest, or political discussion. For respondents whose perceptions of their family’s financial situation shifted from either “getting worse” to “the same” or from “the same” to “improved,” emotional involvement with the political leadership increased by about .08 points on the emotions scale. None of the rest of the control variables seems to matter much, except education. During the course of our survey, eleven respondents reported increased levels of education—it seems they completed their BA in the period between October 2013 and June 2014. These new graduates, the data suggest, increased their level of emotional engagement, too.

In online appendix A, we also look at the effects of collective engagement by round, focusing on levels, not change. Table A2 presents the relationship using OLS regression with standardized betas in round 1 and table A3 shows the relationships in round 2. The results strongly confirm the effects we show with the change models. In round 1, before Crimea, there is a relationship between state television watching and emotional engagement, but this relationship is substantially larger in round 2. Even more interestingly, there is no relationship between discussing politics or interest in politics and emotional engagement before Crimea. Afterwards, both of these relationships are statistically significant and substantively important. This is further evidence of the role of collective engagement in driving the emotional wave.

Proposition 2: Emotions and Perceived Wellbeing

Our second set of hypotheses concerns the effects of positive emotions. Following the theory, increased emotional engagement should be associated with more than just support for the leadership. Rather, it should be associated with a much broader improvement in citizens’ sense of how their country is faring, both politically and economically. We thus sought to measure the impact of the relationship between the Crimean moment and Russian respondents’ evaluation of what was going on in their lives, and in their society as a whole.

To demonstrate the breadth of changes, we measured outcomes in four ways. We began by looking at support for the Kremlin, defined specifically in terms of approval. However, we also wanted to see evidence of change in elements much more distant from emotional engagement with the leadership. To capture this, we asked citizens about important elements of politics and life that we would not have expected to change in any meaningful way (at least not in a positive way) as a result of the annexation of Crimea: corruption, and economic performance. Finally, we asked about something that could not even conceivably have been affected by Crimea—the past.

We measured perceived corruption in two different ways. First, we asked citizens on a three-point scale to tell us how big a problem they felt corruption to be at the top level of politics in Russia. Second, we asked them to give us their sense of low-level corruption. In both cases, we would expect that increased emotional engagement should be associated with decreases in the extent to which corruption is perceived to be a problem. High-level corruption perceptions are of interest because they tap into feelings about the elite, largely insulated from the effects of the actual day-to-day experiences of the respondents. Since the rounds of our survey were separated not only by the annexation of Crimea, but also by the Sochi Winter Olympics, which were a showcase for massive state spending filtered through the pockets of close Putin allies, we might expect high-level corruption to be more prominent in the minds of our respondents in round 2 than in round 1. Low-level corruption, by contrast, is something that citizens might encounter in the normal course of their lives, and so positive emotions about the situation in general are more likely to be tempered by their own actual experiences. There is no evidence that the incidence of low-level corruption in Russia changed in this period.

We also measured how citizens felt about Russia’s economic future. Specifically, we asked whether respondents felt that the Russian economy would improve, stay the same, or decline over the next five years. Again, we expect increases in emotional engagement to be associated with increases in optimism about the economy – even though most commentators (and even prominent government officials) felt that the annexation of Crimea was more likely to be a burden than a benefit.

Finally, we measured the effect of increased emotional engagement on perceptions of the past. Specifically, we asked respondents whether their family had been made better or worse off by the reforms of the 1990s. This is a crucial test, because the empirical facts of the situation could not possibly have been changed by the Crimea-related events, only the perception. We used a three-point scale—worse off, no change, and better off.

To analyze the effect of changes in political discussion on positive emotions in round 2 and the subsequent consequences of emotions, we use the mediation package in R based on the same OLS model with fixed effects and the full range of controls used in Table 1 (Tingley et al. Reference Tingley, Yamamoto, Hirose, Keele and Imai2014). For reasons of space, we show here only the results of the mediated effects of engaging in more political discussion, though the results hold for our other measures of participation—watching state television and political interest (refer to online appendix E).

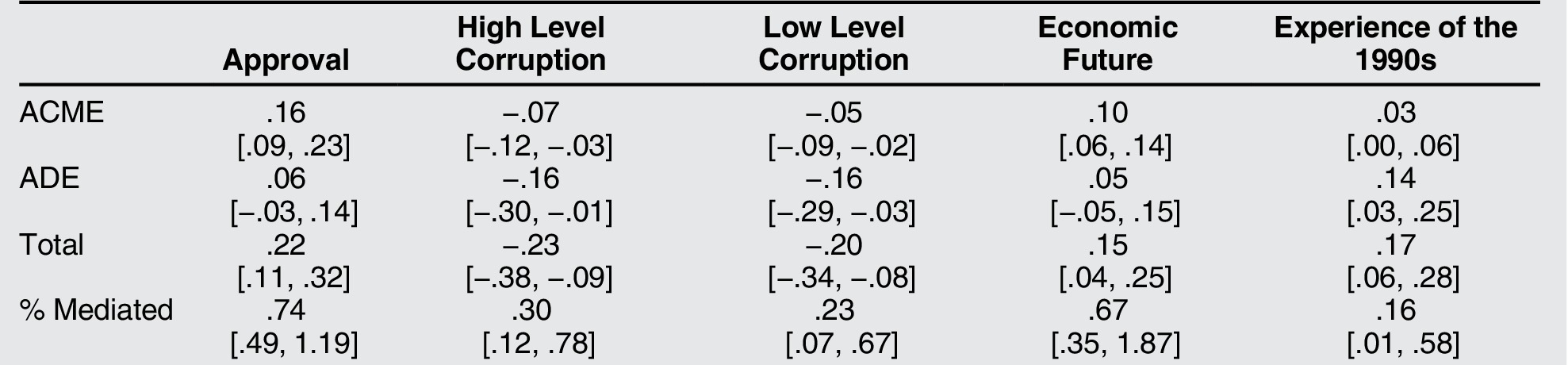

The results are presented in Table 2, for each measure of approval, corruption and economic perceptions, showing the average causal mediation effect (ACME) of changes in discussion, the average direct effect (ADE) and the total effects. The ACME represents the effect of changes in discussion on outcomes that runs through changing emotions. The ADE represents the effect of discussion on these various outcomes that occurs through channels other than changing emotions. These alternative channels could, for example, include learning or the exchange of information that takes place in the context of political discussion. Upper and lower bounds using 95% confidence intervals are in parentheses. We present the results here, before turning to caveats on interpretation.

Table 2 Engagement, emotions, and attitudes Causal mediation analysis

OLS regressions with individual fixed effects.

Table 2 provides good evidence for the role of greater engagement in politics in changing people’s views of non-proximate issues and of the role of emotions in shaping those effects. In all cases, there is a substantial association between increased discussion and the outcome variable—a one standard deviation change in discussion (.9 on 5-point scale) is associated with a .15 to .23 standard deviation change in the various outcome variables. These changes are statistically significant at .95 two-tailed. In each case, the mediation effects through emotions are also statistically significant, though the degree of mediation varies. For changing views of the 1990s and corruption perceptions, there are strong direct effects, but emotions also play a substantively important role. By contrast, for approval and views of the economic future, the direct effects are not statistically significant and most of the association with discussion runs through changes in positive emotions.

What Is the Role of Nationalism?

One possible alternative to the emotions-based story we tell here—and, indeed, one with much currency in the popular press—is an identity-based story. In this argument, citizens who are more patriotic are more likely to increase their approval of the president following Crimea (Hale Reference Hale2018). In this section, we demonstrate that while increased nationalist feeling is associated with increases in approval, the relationship is inconsistent across our dependent variables and disappears when we take into account positive emotional engagement with the leadership.

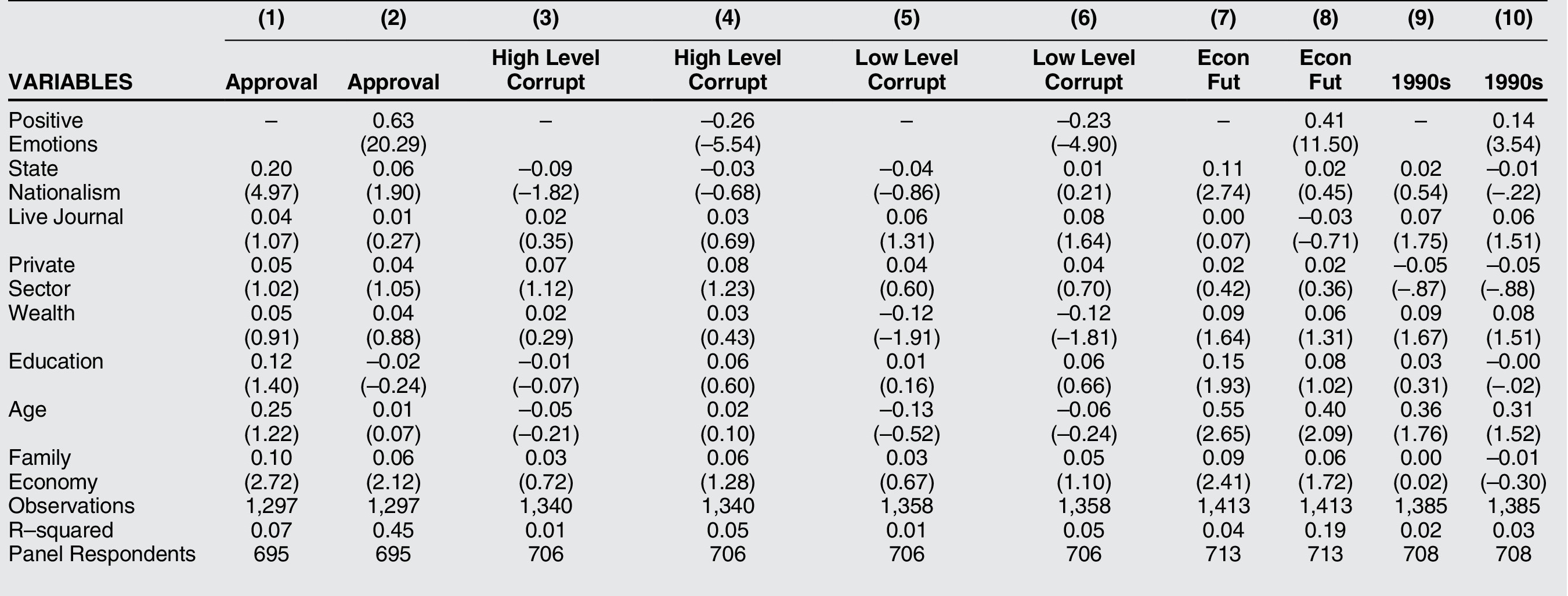

In Table 3, we compare the relationship between state nationalism and our outcomes with the relationship to changes in positive emotional engagement. We measure state nationalism by asking respondents how important to them personally on a 1–5 scale is being part of the Russian state. In online appendix F, we show that this particular measure of nationalism is the one that changes most between rounds and is the strongest competitor as an alternative explanation to our story. Nevertheless, as Table 3 shows, the relationship with nationalism is weak and disappears once we control for changes in emotions.Footnote 10

Table 3 Nationalism and attitudes

OLS regressions with individual fixed effects. Beta Coefficients with t-statistics in parentheses.

Model 1 shows that increasing patriotism is associated with increases in approval, though the effect is no longer statistically significant when we include changes in positive emotions (model 2). The same is true for model 7, which suggests a relationship between increased nationalism and perspectives on the economic future, which again disappears when we control for emotions (model 8). In none of the other cases is there any relationship between nationalism and measures of perceptions of corruption and economics.

Challenges to Inference

The real-world nature of our research imposes certain limitations on our conclusions. Here we are primarily focused on unpacking the chain that goes from engagement and emotions to changing perceptions of the regime, but there are some questions we cannot answer. The important question of what causes increased engagement with politics is one of them. Clearly, there was something powerful for a Russian audience about the particular foreign policy event we study here, but identifying those elements in a theoretically portable way is beyond the scope of a single case like ours.

Similarly, we cannot tell definitively whether collective engagement increases emotional engagement, or the other way round. It is not even clear that the question itself makes much sense. As we have argued, it seems strange to think of either variable—increasing collective engagement or increasing emotional engagement—as being only a cause or only an effect. Moreover, our argument does not require purely unidirectional causation from engagement to emotions. Instead, our point is that engaging more in the collective experience of politics and becoming more emotionally engaged are interactive processes, rising together, as our data show, over time.

At the second stage—the mediation analysis—the evidence is stronger that it is emotions driving change in opinions rather than some omitted variable or the relationship being the other way a round. While we cannot show definite proof of causality with observational data like this, there are a number of reasons to think our story is more plausible than any alternative.

A key challenge to our argument would arise if there were some other variable that drove both engagement and our various dependent variables. If there were, then we would violate a key assumption underlying the mediation analysis – sequential ignorability. Sequential ignorability requires that we can treat the mediator as if it is randomly assigned, conditional on observables. In other words, our claims about mediation would be dubious if three conditions held: if there were a variable that drives both engagement and our dependent variables that is not included in the covariates in the analysis; if that variable changes between the panel survey dates; and if that variable is correlated with emotional engagement and all the dependent variables in the analysis.

To illustrate the point, consider the two most plausible alternative stories. One possibility is that the success of the Crimea annexation increased perceptions of the competence of the government, particularly coming on the heels of the very successful Sochi Olympics. This story of competence is indeed an alternative to our emotions story and meets two of our three criteria—perceptions of competence is not one of our covariates and may change between panel survey dates. But it fails on the third criterion. While evaluations of the competence of the leadership may have improved and so affect some of our dependent variables (perhaps approval and economic perceptions), there is no plausible connection between competence of Putin’s Kremlin and perceptions of how respondents fared in the 1990s, when the current rulers were not in power. Another possibility is that a reaction against western sanctions might drive both emotional engagement and approval—but again, what this could possibly have to do with economic experiences in the 1990s is unclear. Indeed, since part of Putin’s case for his own power is based on a story of how awful the 1990s were, the fact that we find improved perceptions of the 1990s testifies to the emotional nature of these evaluations.

More generally, there is other empirical evidence to suggest that there is no omitted variable driving all the results. We have already demonstrated that the best candidate for such a variable—nationalism—cannot explain what we see. Moreover, if there were such a variable, we would find that, however we run the analysis, all of the different outcomes that we look at would predict each other: all things would rise together. They do not. As we showed in table 2, there is no statistically significant direct connection between political discussion and approval or perceptions of the economic future. In online appendix D, we further show that if we reverse the analysis—using emotions as the outcome and our current dependent variables as mediators—it is not the case that all of our second stage outcomes are simply related to one another. Changes in perceptions of the economy and of corruption are not correlated with one another. High- and low-level corruption perceptions do shape each other, and economic perceptions of the future and the past shape each other, but emotions matter in every case and are always the biggest influence. This is consistent with our argument that emotions play an independent role in shaping perceptions of both kinds, and inconsistent with a story of an omitted variable driving all of the observed outcomes.

Discussion

We have pointed to the importance of positive emotional engagement in undergirding support for a contemporary authoritarian ruler, in the context of an international conflict. Building on work primarily in sociology, we have argued that participation in the collective experience of what we called the “Crimean moment” was a key factor in generating positive emotional engagement with the leadership. Furthermore, we showed that this increase in emotional attachment had substantial consequences for politics. We show clearly that post-Crimea approval for Putin is not a simple story of popular approval of annexation as a matter of policy, nor even the result of latent or resurgent nationalist sentiment. Rather, the Crimean moment as experienced on television and in society creates approval for Putin by increasing the emotional excitement of citizens. This, in turn, helped citizens to feel better not only about their leadership, but also about their country’s present and future, and even their own family’s past. Without emotions, the analysis suggests that Putin’s approval would not have been nearly so stratospheric. While we cannot know exactly, these emotions may also have played a role in the remarkable durability of Putin’s popularity, which only began to fall in summer of 2018, more than four years later.

The analysis here contributes to our understanding of rally events by investigating how a rally can work in an authoritarian state where, unlike in a democracy, elites are almost always publically unified and the media is always a cheerleader for the regime. What distinguish rallies from normal politics in the authoritarian context are not changes in elite dynamics, but changes in the way society responds. In an authoritarian rally, the key element is a dramatic increase in engagement in politics and in discussing politics on the part of citizens. While the regime itself could not have predicted the effects of its actions in Ukraine, those actions and the propaganda around them reverberated in dramatic ways across Russian society, radically shifting citizens’ engagement with politics and with the regime. The consequences of this were profound, wide-ranging, and long-lasting. In shifting the analysis to the emotional foundations of rallies, however, this research raises important questions about how these foundations might eventually erode—or else be bolstered by ratings-hungry autocrats. Indeed, by the time this article went to press, Putin’s support had already substantially decayed.

Finally, our analysis suggests an important alternative research agenda to the dominant institutional approaches in the field of comparative authoritarianism. Without denying the importance of repression and material rewards, our analysis suggests that we should recognize the role that positive emotion may play in keeping dictators in power. Russia, of course, is just one authoritarian regime, and the Crimean moment is itself extraordinary. Consequently, it might be objected that the arguments we are making are exceptional or in some sense aberrant. History, however, suggests that it may be the demobilizational model of authoritarianism that is aberrant. Historians and others working on places as disparate as Nazi Germany (Arendt Reference Arendt1973), Italy (Berezin Reference Berezin2002), and the Dominican Republic (Turits Reference Turits2003) have written about the importance of emotion in supporting authoritarian rulers. Moreover, materialist and institutionalist perspectives have struggled to make sense of the durability of regimes like Putin’s, Erdogan’s, and Chavez’s in the face of economic hardship, and of the “backsliding” of supposedly consolidated democratic systems in Hungary and Poland, and even of the populist turn in the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere. Our research elucidates the ability of leaders to benefit from the sense of community that emotionally charged events can create. Research will show the extent to which the same can be said of other authoritarian leaders, but the power that Putin enjoys including his remarkable ability to remain popular despite four years of declining real incomes rests at least in part on the positive emotions of millions of ordinary Russians.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720002339.