Introduction

Chagas disease is a neglected disease affecting 6–7 million people in Latin America (World Health Organization, 2015). The disease is caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) and transmitted by triatomines, hematophagous insects from Triatominae subfamily (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Trypanosoma cruzi displays a wide genetic diversity and has been grouped in seven discrete typing units (DTUs) (TcI-TcVI and Tcbat) (Marcili et al., Reference Marcili, Lima, Cavazzana, Junqueira, Veludo, Maia Da Silva, Campaner, Paiva and Teixeira2009; Zingales et al., Reference Zingales, Andrade, Briones, Campbell, Chiari, Fernandes, Guhl, Lages-Silva, Macedo, Machado, Miles, Romanha, Sturm, Tibayrenc and Schijman2009). This genetic variability correlates with their geographic distribution and ecological and epidemiological associations. The development of T. cruzi in the vector is related to several factors linked to triatomine species and/or parasite lineage. Historically, assessment of susceptibility of different triatomine species to T. cruzi strains started since 1940s. At the time, xenodiagnosis was the only diagnostic method available in most endemic areas. In the search of a high susceptible vector that could increase the sensitivity of this parasitological test, Dias (Reference Dias1939) compared the susceptibility of Panstrongylus megistus and Rhodnius prolixus to a given T. cruzi strain and found infection rates of 90.4 and 54.7%, respectively. Little et al. (Reference Little, Tay and Francisco1966) found Triatoma barberi to be more susceptible to some Mexicans strains of T. cruzi than Triatoma infestans. Other study compared the ability of nine triatomine species to Y strain (TcII) and found that sylvatic species such as P. megistus and Rhodnius neglectus were more susceptible to infection compared to domiciliated T. infestans/R. prolixus (Perlowagora-Szumlewicz and Müller, Reference Perlowagora-Szumlewicz and Müller1982). Consistent with those observations, nine species (domestic and sylvatic) of triatomines were later infected with three different strains of T. cruzi (Perlowagora-Szumlewicz et al., Reference Perlowagora-Szumlewicz, Muller and Moreira1990). Again, regardless parasite strain sylvatic triatomines were more susceptible to infection. In another study, Y, CL and YuYu strains were able to sustain infection in T. infestans. However, Y strain developed a moderate infection in this vector compared to the other strains exhibiting lower numbers of metacyclic trypomastigotes (Alvarenga and Bronfen, Reference Alvarenga and Bronfen1997). Although most of the studied vectors can be susceptible to various T. cruzi strains, the mechanisms underlying susceptibility rates and kinetics of infection during migration through the intestinal tract are still very scarce.

A few detailed studies have focused on the morphogenetic processes that occur in T. cruzi along the digestive tract of triatomines. Those include the differentiation of ingested blood trypomastigote forms to epimastigotes/intermediate forms, multiplication and development of infective metacyclic trypomastigotes (Brener, Reference Brener1973). Interestingly, these morphological changes may occur even in the absence of blood suggesting that factors released by the intestinal tract may affect this phenomenon (Alvarenga and Brener, Reference Alvarenga and Brener1978). Since most of the studies have focused on the final ability of triatomine vectors to sustain infection and achieve metacyclogenesis, studies on parasite kinetics are still in its infancy. Gaps still exist especially during escape/differentiation from the anterior to the posterior parts of the midgut. In this context, a recent study has explored the interaction of T. cruzi (CL strain) in R. prolixus (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016). In this vector, a reduction of 80% in the parasite numbers in the anterior midgut (AM) was detected after 24 h of parasite ingestion and only a residual population [detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)] was observed in this intestinal region after 96 h. A significant increase in parasite mortality observed in in vitro experiments, where trypomastigotes were incubated with the AM of recently fed nymphs, indicated that this T. cruzi strain is eliminated from the AM of R. prolixus (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016). The absence of a multiplicative population of T. cruzi in the AM of triatomines has also been reported in other studies (Dias, Reference Dias1934; Brener, Reference Brener1972; Dias et al., Reference Dias, Guerra, Vieira, Perdomo, Gandara, Amaral, Vollu, Gomes, Lara, Sorgine, Medei, de Oliveira and Salmon2015), but the details of this part of the midgut colonization process are still unknown.

Triatoma infestans is the main vector of T. cruzi in the southern cone of South America due to its strong adaptation to human dwellings (Waleckx et al., Reference Waleckx, Gourbière and Dumonteil2015) and its capacity to competitively displace other species (Silveira et al., Reference Silveira, Feitosa and Borges1984; Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Gontijo, Guarneri, Sant'Anna and Diotaiuti2006).

As part of a wider study on T. cruzi–triatomine interaction, we explored the susceptibility of T. infestans to three T. cruzi DTUs (I, V and VI) frequently isolated from this species (Brenière et al., Reference Brenière, Waleckx and Barnabé2016). We also evaluated the kinetics of parasite colonization after insect exposure to epi-and trypomastigotes. We intended to elucidate unknown aspects during early interaction of T. cruzi in the T. infestans intestinal tract.

Material and methods

Cell culture and insect maintenance

Trypanosoma cruzi strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Epimastigote forms from all strains were grown in LIT medium supplemented with 15% FBS, penicillin (100 U mL−1) and streptomycin (100 μg mL−1) (27°C and pH 7.2). Triatoma infestans were obtained from a laboratory colony derived from insects collected in Brazil and maintained by the Reference Laboratory of Triatomines and Epidemiology of Chagas Disease, René Rachou Institute, Fiocruz. Triatomines were reared at 25 ± 1°C, 60 ± 10% relative humidity and natural illumination. Fourth instar nymphs starved for 30 days were used in the assays.

Table 1. Trypanosoma cruzi strains, hosts, geographical origin and lineages used in the study

Susceptibility assays

Artificial infection of T. infestans was performed with glass feeders connected to a water bath as previously reported (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016; Guarneri, Reference Guarneri, Michels, Ginger and Zilberstein2020). Insects were fed on citrated heat-inactivated (56°C 30 min−1) rabbit blood mixed with each strain of T. cruzi (1 × 107 parasites mL−1). Rabbit blood was provided by CECAL (Centro de Criação de Animais de Laboratório, Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro). After 28 and 49 days post infection (dpi), 15 nymphs of each group were fed on citrated rabbit blood and transferred to 1.5 mL eppendorffs for urine recovery. Ten μL of each sample was fixed in 10% methanol and stained with Giemsa® for trypomastigote quantification. For parasite quantification in the intestinal tract of T. infestans, 20 nymphs were dissected at days 49–50 post infection (these nymphs were fed on citrated rabbit blood on day 30 post infection). The midgut (M) and the rectum (R) were individually transferred to 1.5 mL tubes containing 20 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 0.15 M NaCl at 0.01 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4) and macerated. Parasite quantification was performed in a Neubauer chamber.

Kinetics of infection with epimastigotes from different strains

Triatoma infestans (n = 30 per group) were infected using artificial glass feeders as described above (1 × 107 epimastigotes mL−1 in citrated heat-inactivated rabbit blood) using the strains Dm28c and Bug. AM and posterior midgut + rectum (PM + R) were individually dissected after 3 h (n = 15) and 72 h (n = 15). They were macerated in 20 μL of PBS and parasites counted (Brener, Reference Brener1962).

Kinetics of infection with trypomastigotes of Dm28c strain

This procedure was approved by the Ethical Committee on Animal Handling (CEUA) from Fiocruz (Protocol LW-8/17). Knockout interferon gamma (INF-γ) mice (B6⋅129S7) were injected intraperitoneally with T. cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes obtained from the urine of infected bugs. Infected mice with parasitemia of at least 7.5 × 103 parasites mL−1 were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (150 mg kg−1) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1) and used to feed T. infestans nymphs (each insect ingested 20–30 mg of blood) (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016). Dissections were performed in different periods (3, 24 and 72 h, 7 and 21 dpi) (n = 14 for each period). AM and PM + R were dissected and parasites were counted as described above. To estimate the proportion of developmental forms in the released urine, 5 μL of each sample were fixed in 10% methanol and stained with Giemsa®. The parasites were morphologically differentiated according to the classification for Trypanosomatidae (Hoare and Wallace, Reference Hoare and Wallace1966) which8] considers the relative position of the kinetoplast and flagellum in the parasite's cell body. The forms in which the position of the kinetoplast was not clear were called intermediate forms. Blood and metacyclic trypomastigotes were determined based in the life-cycle moment of the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data were analysed by GLZ models in groups with multiple categories, followed by Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn post hoc test. In groups with a single category, Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn's post hoc and Mann–Whitney's tests were used. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Evaluation of the susceptibility of T. infestans to different T. cruzi strains

The percentage of nymphs with parasites in the midgut at 49–50 dpi varied from 15 to 25% (20, 25, 25 and 15% for Dm28c, YuYu, Bug and CL-Brener, respectively). In positive insects, low concentrations of parasites were observed in similar numbers among the strains (Fig. 1A, Kruskal–Wallis, P > 0.05). Nevertheless, independent from the strain, all examined insects had parasites in the rectum and their densities varied among strains (Fig. 1A, Kruskal–Wallis, P < 0.0001). YuYu strain reached highest parasite numbers followed by Bug, CL-Brener and Dm28c strains (Fig. 1A, Dunn, YuYu vs CL-Brener P < 0.001, YuYu vs Dm28c P < 0.001, Bug vs Dm28c P < 0.001). All strains accomplished metacyclogenesis (Fig. 1B). Indeed, for all strains, the majority of T. cruzi forms in the urine of T. infestans were metacyclic trypomastigotes (100 ± 0, 98.5 ± 6.2, 97.9 ± 61 and 100 ± 0 for Dm28c, YuYu, Bug and CL-Brener, respectively). No statistical differences were observed between the two collection times (28 and 49 dpi) and for this reason, data from both periods were merged (GLZ, gamma distribution, P > 0.05). Metacyclic numbers in the urine varied depending on the strain (Fig. 1B, Kruskal–Wallis, P < 0.0001). Bug strain reached highest numbers followed by YuYu and CL-Brener/Dm28c (Fig. 1B, Dunn, Bug vs YuYu P < 0.05, Bug vs CL-Brener P < 0.0001, Bug vs Dm28c P < 0.0001, YuYu vs Dm28c P < 0.001).

Fig. 1. Trypanosoma cruzi strains produce different parasite loads along the digestive tract of Triatoma infestans. (A) Parasites present in the midgut and in the rectum (intestines were dissected at 49–50 dpi). (B) Metacyclic trypomastigotes present in the urine produced during diuresis (urine was collected at 28 and 49 dpi). Each point represents the quantification of parasites μL−1 of one insect and each horizontal bar corresponds to the median. M, midgut; R, rectum. Asterisks indicate statistical differences among groups (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001).

Evaluation of the initial colonization of T. infestans intestinal tract by T. cruzi

Infection with epimastigotes

To evaluate the initial colonization process of T. cruzi in the intestinal tract of T. infestans, this vector was artificially fed with citrated heat-inactivated rabbit blood containing epimastigotes (Dm28c and Bug). The strains exhibited different patterns during escape from the AM. In nymphs infected with Dm28c, only the AM had parasites at 3 h post infection (Fig. 2A and B). After 72 h post infection parasites were found in both AM and PM + R (Fig. 2A and B). A 44% reduction in the AM was detected between 3 and 72 h post infection (Mann Whitney, P < 0.0001). For nymphs infected with Bug strain, a complete parasite reduction was observed in the AM between 3 and 72 h post infection (Fig. 2C). In the PM + R, a similar profile to that of Dm28c was observed (Fig. 2D, Mann Whitney, P < 0.0001). Interestingly, parasite densities for both strains in PM + R at 72 h almost doubled (Fig. 2B and D).

Fig. 2. Early migration of Trypanosoma cruzi strains in the midgut of Triatoma infestans after epimastigote infection. (A) Parasite counts of Dm28c strain in the anterior midgut and, (B) posterior midgut + rectum. (C) Parasite counts of Bug strain in the anterior midgut and, (D) posterior midgut + rectum. Each point represents the quantification of the parasites μL−1 of one insect and each horizontal bar corresponds to the median.

Infection with blood trypomastigotes

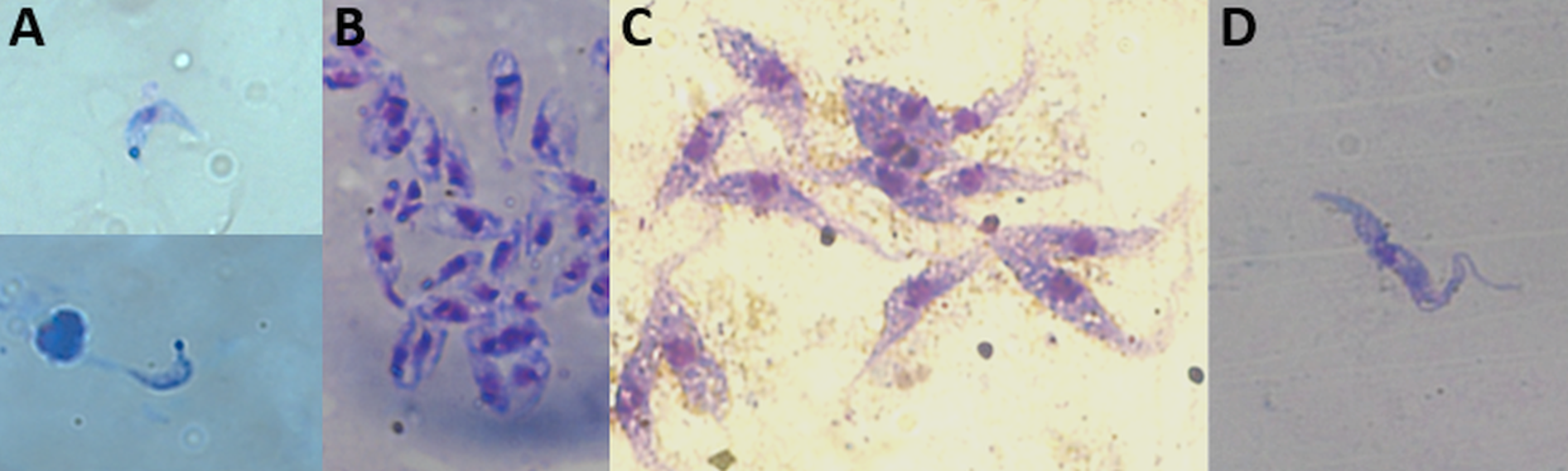

To compare if the evolutive form used for infection could affect parasite escape, nymphs were fed on mice infected with Dm28c strain (Fig. 3). Different from infection with epimastigote forms (Fig. 2A), trypomastigote reduction in the AM was complete at 72 h post infection and no parasites were found at this intestinal portion at 7 and 21 post infection (Fig. 3A). A reduction of 77.1% in the numbers of parasites was found between 3 and 24 h (Fig. 3A, Dunn, P < 0.05). Trypanosoma cruzi parasites were found in the PM + R after 24 h post infection with parasite increase until 21 dpi (Fig. 3B, Dunn, 3 h vs 72 h, 7 and 21d P < 0.0001, 24 h vs 7d P < 0.0001, 24 h vs 21d P < 0.05). Finally, to characterize the kinetics of parasite differentiation, parasites were stained with Giemsa® and morphological forms identified. Following trypomastigote infection, this form was detected between 3 and 24 h post infection in the AM (Figs 4A and 5A). Differently from what was observed in the fresh examination of AM samples in which no parasites were found, at 72 h post infection a few intermediate forms could be identified in the stained preparations (Figs 4A and 5B). In the PM + R samples, intermediate and epimastigote forms were observed at 72 h post infection (Figs 4B and 5C). Metacyclic trypomastigotes were seen at 7 and 21 dpi in PM + R samples, reaching higher proportions in the last time point (Figs 4B and 5D).

Fig. 3. Kinetics of Trypanosoma cruzi (Dm28c strain) migration along the intestinal tract of Triatoma infestans after trypomastigote infection. (A) Parasites found in the anterior midgut and, (B) posterior midgut + rectum. Each point represents the quantification of the parasites μL−1 of one insect and each horizontal bar corresponds to the median.

Fig. 4. Kinetics of Trypanosoma cruzi (Dm28c strain) differentiation (%) along the intestinal tract of Triatoma infestans after trypomastigote infection. (A) Parasites found in the anterior midgut and, (B) posterior midgut + rectum. The numbers of parasites μL−1 found in the different intestinal portions were plotted in the right axis to show the total parasite load in each portion and period. The parasites were counted in Giemsa® stained smears.

Fig. 5. Different forms of Trypanosoma cruzi (Dm28c strain) found in the Triatoma infestans intestinal tract: blood trypomastigotes (A) and intermediate forms (B) in the anterior midgut; epimastigote (C) and metacyclic trypomastigote (D) forms in the posterior midgut + rectum. Giemsa@ stained smear (630 x magnification).

Discussion

After artificial feeding, T. infestans nymphs were susceptible to all T. cruzi strains, which were able to accomplish metacyclogenesis. These data are in accordance with previous studies that showed the T. infestans susceptibility to different T. cruzi strains (Perlowagora-Szumlewics et al., Reference Perlowagora-Szumlewicz, Muller and Moreira1990; Little et al., Reference Little, Tay and Francisco1966; de Lana et al., Reference de Lana, da Pinto, Barnabé, Quesney, Noël and Tibayrenc1998). Moreover, our results showed that the parasite densities in the rectum as well as the concentration of metacyclic trypomastigotes released in the urine were higher for Bug and YuYu than those observed for CL-Brener and Dm28c strains. Bug strain showed lesser parasites in the intestinal tract than YuYu but produced a significantly higher number of metacyclic trypomastigotes released in the urine, which might increase its capacity of transmission. It is worth mentioning that we did not measure the volume of urine produced by the insects, which could affect the total numbers of parasites released. But, as we compared insects from the same instar and species, it is probable that these values did not vary significantly.

In nature, different T. cruzi DTUs circulate between vectors and vertebrate hosts, contributing for the dynamics of infection and parasite maintenance in the environment (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Xavier and Roque2015, Reference Jansen, das Xavier and Roque2018). A recent systematic review analysed 6,343 DTU identifications according to host origins and geographic distribution (Brenière et al., Reference Brenière, Waleckx and Barnabé2016). According to the study, T. cruzi was identified in 158 species, being 42 of them triatomines belonging to seven genera. Triatoma infestans was showed to be infected with all T. cruzi DTUs, but mainly those from TcI, TcV and TcVI (Brenière et al., Reference Brenière, Waleckx and Barnabé2016). Several papers that evaluated the evolutionary relationships among the DTUs demonstrated that TcI is a pure lineage that has evolved separately for a long time, while TcV and TcVI have hybrid origins, probably from TcII and TcIII crossings (reviewed by Zingales, Reference Zingales2018). TcI is the predominant DTU identified in sylvatic and domestic environments, with very wide geographic distribution, while TcV and TCVI are clearly associated with domestic transmission cycles (Brenière et al., Reference Brenière, Waleckx and Barnabé2016). Our results confirmed the high susceptibility of T. infestans to T. cruzi, and highlighted differences in the ability of the different strains to develop in the insect. Indeed, the two TcI strains evaluated, YuYu and Dm28c, showed the best and worse development in T. infestans, respectively. This suggests that other factors rather than genetics may be affecting parasite development.

A small percentage of the examined insects had parasites in the midgut 50 days after the infection, independent of the strain evaluated (15–25%). As already seen in previous studies, T. cruzi seems to concentrate the established populations in the rectum, where parasites can be found free in the rectal lumen and adhered to the rectal wall (Kollien et al., Reference Kollien, Schmidt and Schaub1998; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Kleffmann and Schaub1998). Nevertheless, populations of epimastigotes can also be maintained in the PM (Asin and Catalá, Reference Asin and Catala1995).

The differences in the number of parasites found in the rectum and urine could be a consequence of the dynamics of strains colonization when the infection started. Therefore, we evaluated the process of colonization of cultured epimastigotes of Bug and Dm28c, strains that showed statistical differences in both, the number of parasites present in the rectum and the number of metacyclic trypomastigotes released in the urine. We found that the Bug strain reduced the number of parasites in the AM earlier than Dm28c. These differences did not affect the numbers of parasites found in the PM at 72 h post infection, which were similar for both strains. Nevertheless, the Bug strain reached a larger parasite load than did Dm28c in the long-term infection, perhaps suggesting a better viability of parasites that manage to scape quickly from the AM.

Next, to better understand how Dm28c strain produces such a small number of parasites in long-term infections, we evaluated the colonization process in T. infestans fed on blood trypomastigotes from mice. Interestingly, we found that the dynamics of early colonization differs from that found when epimastigotes were used. No parasites were found in the AM at 72 h post infection when the infection started with blood trypomastigotes, while 66% of the epimastigotes remained there at this time point. These results agree with those observed when R. prolixus were infected with CL and Dm28c strains that also found an earlier reduction of trypomastigotes in the AM of the bugs (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Contreras, Marliére, Guarneri, Silva, Mazzarotto, Batista, Soccol, Krieger and Probst2017). Blood trypomastigotes face several adverse conditions in the AM of the insect when they are ingested by the later during a blood meal. Those include changes in temperature, hydrolytic enzymes, microbiota and immune responses, among others (summarized by Guarneri and Lorenzo, Reference Guarneri and Lorenzo2017). In addition, triatomines ingest part of the released saliva during the blood meal (Soares et al., Reference Soares, Carvalho-Tavares, Gontijo, dos Santos, Teixeira and Pereira2006). Triatoma infestans salivary glands secrete the antimicrobial peptide trialysin, which has been shown to lyse blood trypomastigotes (Amino et al., Reference Amino, Martins, Procopio, Hirata, Juliano and Schenkman2002). Interestingly, the epimastigote forms secrete a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase that binds to and neutralizes trialysin (Kulkarni et al., Reference Kulkarni, Karafova, Kamysz, Schenkman, Pelle and McGwire2013), which could promote a temporary protection to the epimastigotes while they are in the AM. Nevertheless, this region of the intestine seems not to be an appropriated environment for T. cruzi development since several studies report the absence of multiplicative populations of the parasite there (Dias, Reference Dias1934; Dias et al., Reference Dias, Guerra, Vieira, Perdomo, Gandara, Amaral, Vollu, Gomes, Lara, Sorgine, Medei, de Oliveira and Salmon2015; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016). Altogether, those data indicate that regardless the evolutive form used for infection, T. cruzi passage through the AM seems to be very transient.

The time required for T. cruzi to produce metacyclic forms in the triatomine depends on several factors, such as the parasite strain, the triatomine species, the temperature at which the infected insects are maintained and the nutritional status of the bugs (Guarneri and Lorenzo, Reference Guarneri and Lorenzo2017). We found a rapid development of Dm28c strain in T. infestans gut, with metacyclic trypomastigotes appearing at 7 dpi. Similar results were found when T. infestans were infected with the strain X-t and maintained at 28°C (Asin and Catalá, Reference Asin and Catala1995). In the cited study, epimastigotes were observed in the PM from day 1 to day 5 post infection. From day 6, both epimastigotes and trypomastigotes could be found in the rectum (Asin and Catalá, Reference Asin and Catala1995). Interestingly, we found a 100-fold reduction in the number of parasites in the bugs examined at 49 dpi (in the experiment started with epimastigotes) when compared with those examined at 21 dpi (in the experiment started with trypomastigotes). Several factors could have affected these numbers, such as the developmental form of the parasite used to infect the bugs (trypomastigotes leave the AM early than epimastigotes) or the blood used for the infection (rabbit and mice; Schaub, Reference Schaub1989). In addition, insects with long-term infections received two complete blood meals (the first for parasite ingestion, and the second 30 dpi). This could decrease parasite populations due to defecation after the first blood meal, and during the diuresis process and defecation after the second blood meal.

In the experiments that evaluated the colonization process of CL strain in R. prolixus (Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016), a small number of parasites was found in the PM of the bugs at 1, 2, 4, 7 and even 15 dpi. The study showed that in that case parasites suffered a population reduction of >80% in the AM, during the first 24 h after feeding. Therefore, the colonization started with few parasites, which could explain the reduced numbers until 15 days of infection. In the present work, we found almost twice more parasites than the initial number in both Bug and Dm28c strains in the PM at 72 h after ingestion. Specific characteristics of T. cruzi strains or of triatomine species could explain these different results. Regarding T. cruzi strains, Bug and Dm28c strains could be able to rapidly cross the AM of the bug, reaching the PM before being killed. Alternatively, CL strain could be susceptible to factors present in the AM. Regarding triatomine differences, the AM of T. infestans could possess physiological characteristics different from that of R. prolixus, not causing the death of blood trypomastigotes when they arrive in the bug intestinal tract. This last hypothesis seems less probable, since parasites usually do not develop in the AM of T. infestans, in the same way as seen in R. prolixus (the present study and Dias et al., Reference Dias, Guerra, Vieira, Perdomo, Gandara, Amaral, Vollu, Gomes, Lara, Sorgine, Medei, de Oliveira and Salmon2015; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Kessler, Lorenzo, Paim, Ferreira, Probst, Alves-Silva and Guarneri2016). Future experiments infecting T. infestans with CL strain will help us to better understand these differences.

In conclusion, our results show that even that T. infestans is susceptible to strains from different DTUs, the parasites show different dynamics of development in the bug, which can change their abilities to be transmitted to vertebrate hosts. We are aware that the results showed in this study do not exactly reflect the triatomine-trypanosome interaction in nature. We used reference T. cruzi strains that have been maintained for long periods in culture medium, which may affect their original biological characteristics. However, the fact that all strains managed to multiply and complete their development in the intestinal tract of the bug, producing metacyclic forms, indicate that, despite the artificial maintenance, parasites and triatomines still preserve the ability of interaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Reference Laboratory of Triatomines and Epidemiology of Chagas Disease, René Rachou Institute, Fiocruz, for providing the insects used in this study.

Financial support

A.A.G. and R.P.S. were supported by CNPq productivity grants. This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais, FAPEMIG (A.A.G., grant numbers APQ-00569-15 and PPM-00162-17; R.P.S. grant number PPM-X00102-16), Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Entomologia Molecular, INCTEM/CNPq (A.A.G., grant number 465678/2014-9) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, CNPq (R.P.S., grant number 302972/2019-6).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.