Introduction

The genus Spirocerca (Railliet and Henry, Reference Railliet and Henry1911) belongs to the family of nematodes Spirocercidae (Chabaud, Reference Chabaud1959). The taxonomic status of the members of this genus has been subjected to several changes in the past (Chabaud, Reference Chabaud1959; Clark, Reference Clark1981), and to date, Spirocerca lupi (Rudolphi, Reference Rudolphi1819) and Spirocerca vigisiana (Kadenazii, 1946) are the only species ranked in this taxonomic group. Spirocerca lupi was firstly classified as Spiroptera sanguinolenta syn. Strongylus lupi (Rudolphi, Reference Rudolphi1819) and described as a parasitic nematode of carnivores. Later, the genus was changed to Spirocerca, with S. lupi as the type species (Railliet and Henry, Reference Railliet and Henry1911; Spindler, Reference Spindler1933). Other former Spirocerca spp. of mammals and marsupials were reclassified to other genera, such as Cylicospirura and Didelphonema, based on the morphological traits of the anterior end of the body and total body length (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson2009). For instance, Cylicospirura heydoni (Baylis, 1927) was previously known as Spirocerca heydoni, Cylicospirura arctica (Petrow, 1927) as Spirocerca arctica and Didelphonema longispiculata (Hill, 1939) as Spirocerca longispiculata (Stewart and Dean, Reference Stewart and Dean1971).

Spirocerca lupi is a parasitic helminth mainly associated with domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), which induces the formation of the oesophageal nodules that may transform to osteosarcoma or fibrosarcoma in cases of chronic infection (van der Merwe et al. Reference van der Merwe2008). This nematode species has also been reported in several wild canids, including red foxes (Vulpes vulpes; Segovia et al. Reference Segovia2001; Meshgi et al. Reference Meshgi2009; Ferrantelli et al. Reference Ferrantelli2010; Diakou et al. Reference Diakou2012; Morandi et al. Reference Morandi2014; Magi et al. Reference Magi2015), grey foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus; Pence and Stone, Reference Pence and Stone1978), grey wolves (C. lupus; Szafrańska et al. 2010), coyotes (Canis latrans; Pence and Stone, Reference Pence and Stone1978), maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus; Blume et al. Reference Blume2014), bush dogs (Speothos venaticus; Rinas et al. Reference Rinas2009), golden jackals (Canis aureus; Meshgi et al. Reference Meshgi2009) and black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas; Rothmann and de Waal, Reference Rothmann and de Waal2017). Moreover, S. lupi has been reported as a parasite of other mammalian species, including lemurs (Blancou and Albignac, Reference Blancou and Albignac1976; Alexander et al. Reference Alexander2016) and felines (Murray, Reference Murray1968; Pence and Stone, Reference Pence and Stone1978; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Stafford and Coles2016). These reports are mainly derived from the finding of helminth eggs in feces or the macroscopic observation of adult worms in tissue lesions, without using molecular methods or detailed morphometric analyses, with the exception of Rothmann and de Waal (Reference Rothmann and de Waal2017) who characterized a partial sequence of the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene in S. lupi from the black-backed jackal and domestic dogs. Therefore, possible species misidentification in some of the reports above cannot be ruled out.

Recent studies have reported S. lupi-like nematodes in the stomach nodules of red foxes. Al-Sabi et al. (Reference Al-Sabi2014) described the presence of Spirocerca sp. in the stomach nodules of red foxes from Denmark, which had a COI sequence identity of up to 93% with S. lupi. Similarly, Sanchis-Monsonís (Reference Sanchis-Monsonís2015) reported adult stage helminths in the same anatomical location in the red foxes from Spain and identified them as S. lupi based on macroscopic observation. Based on the DNA sequence and phylogenetic data and the different anatomical location where adult worms were located (i.e. stomach), the nematodes described in the red foxes might correspond to a cryptic species of S. lupi (i.e. morphologically identical species but genetically different) or a different species (i.e. both morphologically and phylogenetically distant). In this study, we characterized Spirocerca nematodes collected from the stomach nodules of red foxes and compared them to S. lupi worms from domestic dogs by performing morphological and morphometric analyses, and by molecular identification based on mitochondrial (COI) and nuclear (18S rRNA) genes. We present morphological and phylogenetic findings to support the presence of a different species of Spirocerca in the red foxes designated herein as Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov.

Materials and methods

Collection of samples

Adult stages of Spirocerca sp. and S. lupi were obtained from red foxes (V. vulpes) (Fig. 1A) and domestic dogs, respectively. Carcasses of foxes from the provinces of Valencia, in Spain (n = 286; Alicante and Castellón), from seven regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina (n = 1106; Prozor, Rama, Sanski Most, Kupres, Široki Brijeg, Trnovo and Mostar) and from the Basilicata region in Italy (n = 1; Matera) were obtained from authorized captures as part of predator and post-vaccinal rabies control programmes, from wildlife protection centres, or from road-killed animals after car accidents. Fifty-four Spirocerca sp. worms (26 from Spain, 27 from Bosnia and Herzegovina and one from Italy) from the total number of nematodes found in the stomach nodules after post-mortem analysis (Fig. 1B and C) were maintained in 70% ethanol for further analysis. In addition, S. lupi worms were obtained from the oesophageal nodules at the post-mortem dissection of euthanized dogs from Rishon Lezion, Israel (n = 32), Mizoram, India (n = 5) and Pretoria, South Africa (n = 4) (Supplementary Material Table S1).

Fig. 1. Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. nematodes found in a red fox from the Valencian region, Spain. (A) A red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in its natural habitat. (B) Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. adult found in a nodule located in the stomach wall of a red fox. (C) Multiple nodules located in the stomach wall of a red fox.

Histopathological analysis of lesions

Histopathological evaluation of the parasitic nodules was carried out on the tissues from 26 of the infected red foxes from Spain and 31 from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Stomach wall tissue samples collected for histopathology were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Carlo Erba Reagents, Dasit Group, Italy) for 24–48 h, embedded in paraffin, cut at 4–6 µm width, placed on slides, stained with haematoxylin and eosin and examined under the light microscope.

Morphometric analysis of specimens

Twenty-one adult worms (11 females and 10 males) obtained from red foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Spain and 18 adults (10 females and eight males) collected from dogs in Israel were cleared overnight in lactophenol solution containing 20% lactic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 40% glycerol (Gadot Group, Israel) and 20% phenol (Sigma-Aldrich) and then mounted in glycerol in a paraffin ring. Morphological analysis was performed by visualizing the specimens using a light microscope (Zeiss Primo Star, ZEISS, Germany) equipped with a digital camera (AxioCam ERc 5s, ZEISS). Taxonomically relevant structures of the nematodes (see Tables 1 and 2) were measured using the AxioVision Rel 4.8 software (ZEISS), and the mean and standard deviation were calculated. In addition, digital line drawings were produced by editing photomicrographs using the Inkscape 0.91 (Free Software Foundation Inc., Boston, MA, USA). The measurements of worms and their structures were analysed using the Mann–Whitney test with the GraphPad Prism 7.04 software.

Table 1. Comparative morphometric analysis of anatomic structures of Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. and Spirocerca lupi female adults

s.d., standard deviation; NA, not applicable.

a Measurement done from SEM pictures using the ImageJ v1.48 software (Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri2012).

b Measurements significantly different when comparing S. vulpis sp. nov. and S. lupi (P < 0.05).

Table 2. Comparative morphometric analysis of anatomic structures between Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. and Spirocerca lupi male adults

s.d., standard deviation; NA, not applicable.

a Measurement done with SEM pictures using the ImageJ v1.48 software (Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri2012).

b Measurements significantly different when comparing S. vulpis sp. nov. and S. lupi (P < 0.05).

Scanning electron microscopy analysis

Eleven worms (five females and six males) collected from red foxes from Spain and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and six worms (three males and three females) from dogs from Israel were prepared for electron microscopy. Worms were washed 20 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 min to remove mucus and additional host tissue residues and then fixed in a solution containing 4% formaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 h. The worms were then washed by five passages in PBS, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (25–100%), dried with a critical point dryer (Quorum K850, Quorum Technologies Ltd., UK) with CO2, mounted on aluminium stubs and coated with iridium for 20 s (Quorum Spatter coater Q150 T ES, Quorum Technologies Ltd.). Finally, the samples were imaged in a scanning electron microscope (SEM; JSM-IT100, JEOL USA Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) in a 10 mm stage height operated at 5 kv. Worm structures including teeth-like formations and distances between pre-anal and post-anal papillae were measured using the ImageJ 1.48v software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) (Schneider et al. Reference Schneider, Rasband and Eliceiri2012).

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses

Twenty-two worms collected from red foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina (n = 14), Italy (n = 1) and Spain (n = 7) and 17 collected from dogs from Israel (n = 8), South Africa (n = 4) and India (n = 5) were subjected to molecular analysis (Supplementary Material Table S1). Genomic DNA was extracted from the worms using the Qiagen Blood & Tissue kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was run to amplify a 551 bp partial fragment of the (COI) gene of S. lupi using primers NTF 5′-TGATTGGTGGTTTTGGTAA-3′ and NTR 5′-ATAAGTACGAGTATCAATATC-3′ (Casiraghi et al. Reference Casiraghi2001) as previously described (Rojas et al. Reference Rojas2017a). The absence of co-amplification of nuclear mitochondrial genes (numts) was verified by aligning the obtained sequences with the COI DNA sequence of the S. lupi mitochondrial genome (Liu et al. Reference Liu2013), by visual verification of ambiguities in the sequence chromatograms and by translation of nucleotide to the amino acid sequences using the MEGA6 software (Tamura et al. Reference Tamura2013) to search for stop codons and indels as recommended (Song et al. Reference Song2008).

A 1611 bp fragment of the 18S rRNA gene was amplified with two primer sets. Primers Nem18S-F1 5′-CGCGAATRGCTCATTACAACAGC-3′ and Nem18S-R1 5′-GGGCGGTATCTGATCGCC-3′ (Floyd et al. Reference Floyd2005), and Nem18S-F2 5′-CGAAAGTCAGAGGTTCGAAGG-3′ and Nem18S-R2 5′-AACCTTGTTACGACTTTTGCCC-3′ designed using the PrimerBLAST program (Ye et al. Reference Ye2012) were used, and amplified regions of approximately 750 and 870 bp, respectively. The reactions included primers at a final concentration of 400 nm each and 3 µL DNA in PCR ready-to-use tubes (Syntezza Bioscience Ltd., Israel). Reactions with both primer sets were run using the same protocol: 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles at 95 °C for 1 min, 56 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 2 min, with a final elongation step at 72 °C for 5 min.

PCR amplicons were visualized in a 2% agarose gel with ethidium bromide. PCR products were sequenced using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing chemistry from Applied Biosystems using the ABI3700 DNA Analyser and the ABI's Data Collection and Sequence Analysis software (Applied Biosystems, ThermoFisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

The COI and 18S sequences obtained in this study were aligned using the MEGA6 software (Tamura et al. Reference Tamura2013) with S. lupi, Spirocerca sp., Cylicospirura spp. and Protospirura muricola reference sequences available in the GenBank database. The best nucleotide substitution model was chosen according to the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) option in MEGA6. A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was generated in MEGA6 with 1000 bootstrap replicates using all sites of the sequences. Additionally, a Bayesian inference (BI) phylogram was created using the MrBayes (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, Reference Huelsenbeck and Ronquist2001) plugin in the Geneious software 7.1.9 (Kearse et al. Reference Kearse2012) with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis run for 1 100 000 generations with 100 000 of burn-in length. One phylogram sampled each 1000 iterations and a consensus phylogram was generated by the same software. Cylicospirura felineus (GenBank accession number GQ342967.1), Cylicospirura subaequalis (GQ342968.1), Cylicospirura petrowi (KF719952.1) and P. muricola (KP760207.1) were used as outgroups for the COI trees and C. petrowi (KM434335.1) for the 18S rRNA phylograms. Finally, a Templeton–Crandall–Sing (TCS) network was calculated using COI sequences (Clement et al. Reference Clement, Posada and Crandall2000) with a 95% connection limit using the PopArt software (http://popart.otago.ac.nz).

Results

Lesions associated with Spirocerca sp. in infected animals

Spirocerca sp. worms collected from red foxes were found mainly in the gastric nodules (Fig. 1B and C). Twenty-two per cent [63/286, 95% confidence interval (CI) 17.4–27.3%] of the red foxes from Spain were infected with Spirocerca sp. adults and 96.8% (61/63, 95% CI 89.0–99.6%) and 7.9% (5/63, 95% CI 2.6–17.6) of them had nodules in the stomach wall or major omentum, respectively. Additionally, one of the infected foxes had nodules in the mesenterium and another fox harboured one nematode in a pericardium nodule (Sanchis-Monsonís, Reference Sanchis-Monsonís2015). Moreover, 9.5% (105/1106, 95% CI 7.8–11.4%) of the red foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina were infected with Spirocerca sp., of which 96.2% (101/105, 95% CI 90.5–98.9%), 10.5% (11/105, 95% CI 5.3–18.0%) and 1.9% (2/105, 95% CI 2.3–6.7%) had nodules in the stomach, omentum or aorta, respectively. The nodules were grey to brown in colour, firm, circular to discoid and had a smooth surface without perforation or necrotic lesions. Their diameter ranged from 0.5 to 4.7 cm, varying according to the number of worms and the anatomical location within the fox. Most of the nodules were encircled by a red rim of hyperaemia or haemorrhage and those in the stomach were most commonly observed on the serosa or incorporated in the gastric wall (Fig. 1B and C).

Aneurisms in the cranial and caudal thoracic aorta were found in 1.8% (5/286, 95% CI 0.6–4.0%) of the foxes from Spain. Notably, nodules with adult worms were not found in these five animals (Sanchis-Monsonís, Reference Sanchis-Monsonís2015). Furthermore, 1.9% (2/105, 95% CI 0.2–6.7) of the red foxes from Bosnia and Herzegovina also had thoracic aorta aneurisms and a few cross-sections of nematode parasites were observed in these lesions.

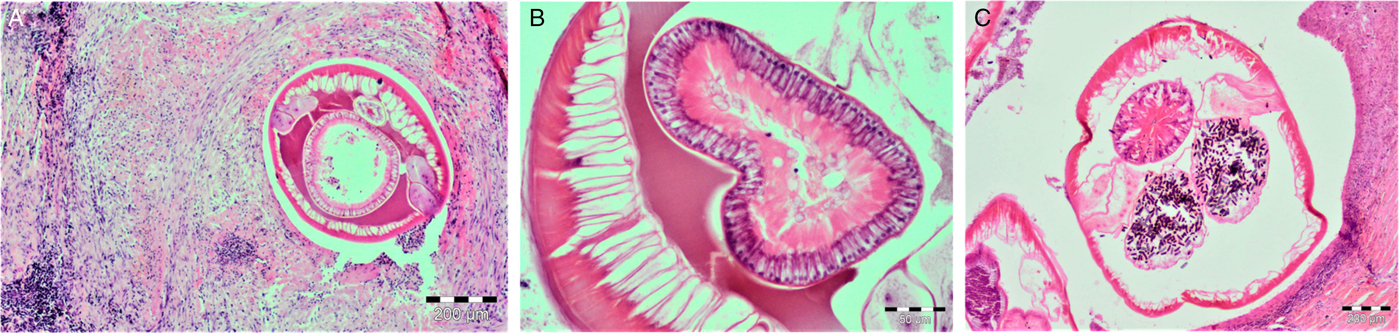

Histopathology of the stomach nodules revealed granulomatous lesions with cellular infiltrates surrounding nematodes (Fig. 2A). The nodules showed a central cavitary space containing multiple cross-sections of nematode parasites surrounded by an eosinophilic and granular exudate. Parasites had striated cuticle, celomyarian musculature and large lateral cords. The intestine was large and composed of uninuclear cuboidal cells with eosinophilic often vacuolated cytoplasm and prominent brush border (Fig. 2B). Multiple sections of uteri were filled with embryonated eggs (Fig. 2C). In the pseudocoelom, eosinophilic material surrounded the intestine and uterine sections. In addition, numerous eosinophils, plasmatic cells, macrophages and, in lesser numbers, lymphocytes and neutrophils were observed around the worms. Moreover, multiple layers of dense collagen and fibroblasts were present in the outer wall of the nodules. In contrast, all S. lupi nematodes from domestic dogs were found in the oesophageal nodules. These nodules had a smooth surface with a nipple-like protuberance and shared the characteristics described by van der Merwe et al. (Reference van der Merwe2008).

Fig. 2. Gastric nodules with Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. worms stained with haematoxylin–eosin. (A) Layers of fibrotic material with lymphocyte, plasma cell, eosinophil and macrophage infiltration. (B) Cross-section of S. vulpis sp. nov. gut showing cuboidal cells with apical brush borders. (C) Cross-section of a S. vulpis sp. nov. female with uterus containing embryonated eggs. Scale bar in A and C = 200 μm, B = 50 μm.

Morphological analyses

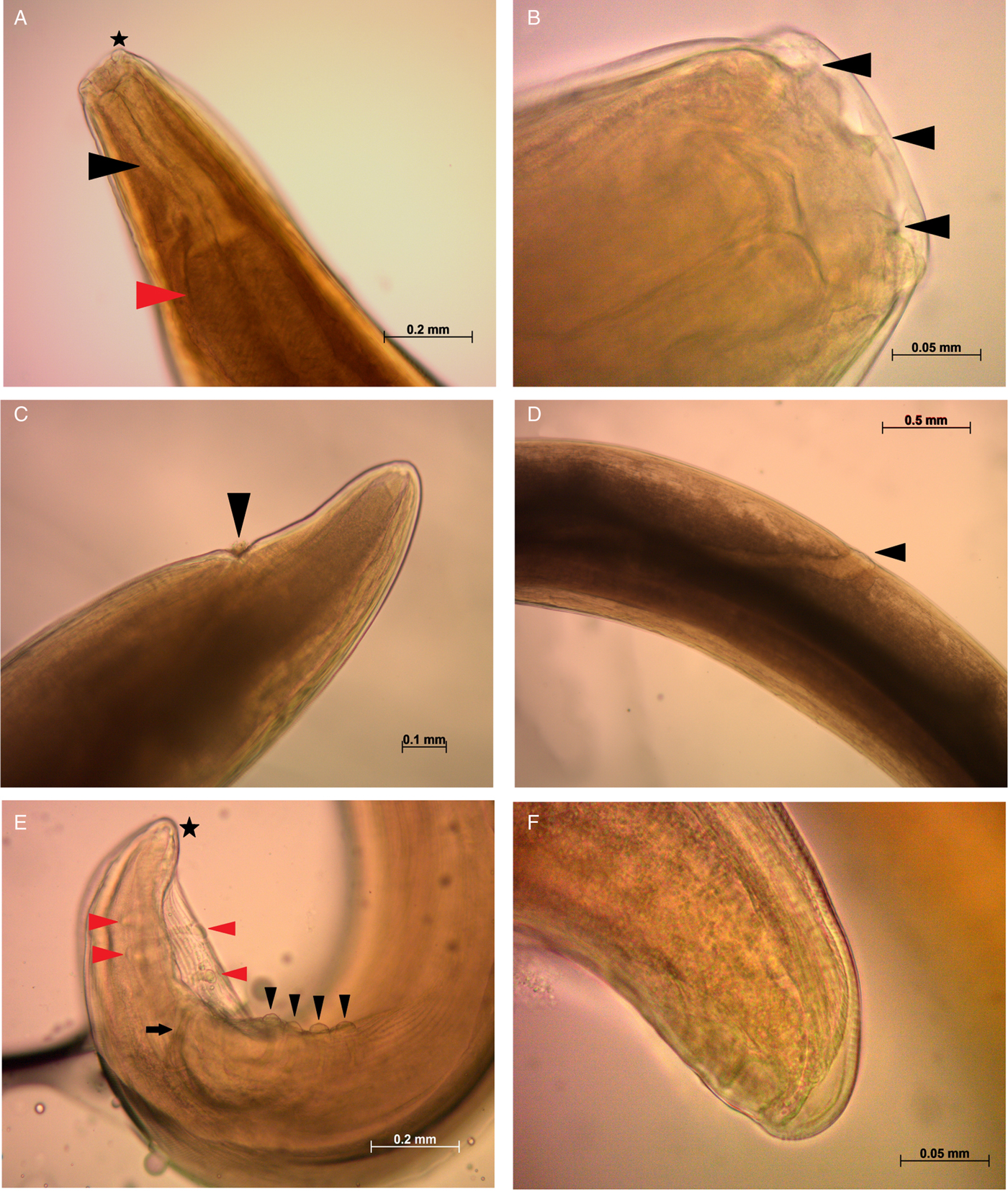

All Spirocerca sp. adult specimens shared the same morphological characteristics including colour (i.e. red or pink), length, body structures of the anterior and posterior parts and measures. Females were usually larger than males and shared the same anterior end structures. These consisted of a highly sclerotized buccal capsule (Fig. 3A and B) and four cephalic papillae with one pair of amphids (Figs 4A, B, 5A and C). Importantly, these specimens had six teeth emerging from the buccal capsule evident both by SEM and light microscopy (Figs 3A, B, 4A, B and 5C). The posterior end of the females showed a slit-like anus (Figs 3C and 4C) and one terminal papilla (Fig. 4D). Moreover, the females had a uterus containing mostly embryonated eggs (Fig. 5B) and with a simple vulva without lips or additional structures (Fig. 3D). The posterior end of males consisted of four pairs of pre-anal papillae and two pairs of post-anal papillae (Figs 3E, 4E, F and 5D), and an irregularly shaped gubernaculum (Fig. 3F). The morphological characteristics of S. lupi nematodes from domestic dogs were compatible with the previous descriptions of this species (Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Material Fig. S1) (Rudolphi, Reference Rudolphi1819; Goyanes Alvarez, Reference Goyanes Alvarez1937), with a sclerotized buccal capsule, four cephalic papillae and one pair of amphids in the anterior end.

Fig. 3. Light microscopy images of Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. adult females and males. (A) Anterior part of the body of a female specimen showing the cephalic papillae (black star), muscular oesophagus (black triangle) and anterior portion of the glandular oesophagus (red triangle). (B) Triangular teeth-like structures (black triangles) emerging from the buccal capsule to the oral opening. (C) Anal opening (black triangle) observed in the posterior end of a female. (D) Vulva opening (black triangle) observed in a female. (E) Posterior end of a male showing pre-anal (black triangles) and post-anal papillae (red triangles), minor spicule (black arrow) and gubernaculum (black star). (F) Close-up of the irregularly shaped gubernaculum in the posterior end of a male. Scale bars are shown in each picture.

Fig. 4. Scanning electron microscopy of Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. specimens. (A) Anterior end showing four cephalic papillae, oral opening and teeth-like structures emerging from the buccal capsule. (B) Close-up of oral opening depicting six teeth and one pair of amphids ventrally and dorsally positioned. (C) Posterior end of a female showing anal opening. (D) Posterior end of a female with terminal papillae. (E) Posterior portion of a male displaying minor spicule, pre-anal and post-anal papillae. (F) Close-up of pre-anal papillae and short parallel longitudinal striations. Scale bars are shown in each picture.

Fig. 5. Line drawings of S. vulpis sp. nov. (A) Anterior portion of a female showing muscular and glandular oesophagus, gastro-oesophagic junction, vulva opening and posterior end of the uterus. (B) Thick-layered egg with larva inside. (C) Close-up of the anterior end depicting lip-like crescents in the mouth opening and teeth, sclerotized buccal capsule and anterior end of the muscular oesophagus. (D) Posterior part of a male illustrating gut, cloaca, minor and greater spicules, pre-anal and post-anal papillae, gubernaculum and ventral longitudinal striations. Scale bars shown in each drawing.

The eggs of Spirocerca sp. from red foxes were elongated, thick shelled and morphologically undistinguishable from those of S. lupi. In the proximal uterus, the eggs were fully embryonated, while non-embryonated eggs were observed in the distal portions of the uterus.

The comparison of adult specimens of both Spirocerca spp. revealed significant differences in some anatomical structures. In females, the ratio of the glandular-to-muscular oesophagus length was significantly larger in Spirocerca sp. from foxes compared with S. lupi (P = 0.004) and the same was found for the distance between the vulva opening and the anterior end (P = 0.0238) (Table 1). In male nematodes, the whole oesophagus and glandular oesophagus lengths, the ratio of the glandular-to-muscular oesophagus lengths and the percentage of the oesophagus length to the total body length were significantly larger in S. lupi as compared with Spirocerca sp. (all P < 0.0238) (Table 2).

Molecular and phylogenetic analyses

The analysis of the COI partial sequence (551 bp) showed that the interspecific nucleotide distances ranged from 7.8 to 10.6% (average: 9.2 ± 0.4%) between Spirocerca sp. specimens from foxes and S. lupi. The intraspecific nucleotide distance within the Spirocerca sp. from foxes ranged from 0.1 to 2.6% (average: 0.7 ± 0.6%) and 0.2 to 3.8% (average: 2.1 ± 0.1%) in S. lupi specimens. The nucleotide differences between the reference sequence of Spirocerca sp. from Danish red foxes (KJ605487.1) (Al-Sabi et al. Reference Al-Sabi2014) and the sequences from Spirocerca sp. from red foxes from this study ranged from 0.2 to 1.3%. Additionally, the distance between Spirocerca sp. from foxes and C. petrowi (KF719952), C. felineus (GQ342967), C. subaequalis (GQ342968) and P. muricola (KP760207) ranged from 10.2 to 16.1% (average: 12.9 ± 1.5%). When comparing S. lupi with Cylicospirura spp. and P. muricola, the pairwise distances ranged from 10.6 to 18.4% (average: 13.0 ± 2.7%) with the highest value recorded when comparing S. lupi from Israel and P. muricola (18.4%). Importantly, the sequences were well resolved in the chromatograms, aligned correctly to the reference mitochondrial genome (Liu et al. Reference Liu2013) and, when translated, there were no stop codons in the amino acid sequences, suggesting the absence of co-amplified numts. Finally, translated protein sequences in the COI gene showed five amino acid changes between Spirocerca sp. from foxes and S. lupi from dogs, namely, from tyrosine to cysteine, serine to phenylalanine, proline to leucine, glutamate to valine and aspartate to alanine.

A nearly full-length DNA sequence of the 18S rRNA gene (1611 bp) was obtained from all specimens (n = 37). This gene showed less variability between S. lupi and Spirocerca sp. in comparison with the COI sequences. Accordingly, the interspecific nucleotide pairwise distance ranged from 0.19 to 0.25% between Spirocerca sp. from red foxes and S. lupi and four indels in sites 76, 107, 126 and 580 and an A–G transition in position 129 were identified. The sequences of Spirocerca sp. from red foxes (n = 20) were identical to each other, except for one sequence which had a single transversion from G to C in position 848. All sequences of S. lupi (n = 17) were 100% identical to each other. Moreover, Spirocerca sp. and S. lupi showed a pairwise distance of 3.12 and 5.00%, respectively, to an 18S rRNA reference sequence obtained from a Spirocerca sp. from a fox in the USA (AY751498). Finally, both Spirocerca spp. had a pairwise distance of 0.54% to C. petrowi (KM434335) from a wildcat in Germany.

Phylogenetic analysis using the BI and ML methods showed that the specimens of S. lupi and Spirocerca sp. from red foxes formed monophyletic sister clades with high support when analysing the sequences of the COI and 18S rRNA genes (Figs 6 and 7 and Supplementary Material Fig. S2), and Jukes–Cantor model according to the AIC results. The COI sequence of Spirocerca sp. from Danish red foxes (GenBank KJ605487.1) grouped in the same clade with Spirocerca sp. obtained from the foxes in this study. Conversely, the COI fragment from the whole mitochondrial genome of S. lupi (Liu et al. Reference Liu2013) clustered together with the S. lupi sequences, within those obtained from India in this study. The parsimony network replicated the same observations as the phylograms with COI sequences of Spirocerca sp. from the foxes grouped in a separate cluster than S. lupi.

Fig. 6. Phylogenetic analysis of the COI gene 551 bp fragment of Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. compared with Spirocerca lupi, Cylicospirura spp. and Protospirura muricola. Maximum likelihood (ML) (A) and Bayesian inference (BI) (B) trees show bootstrap replicate values and posterior probabilities, respectively. Host, geographical location and GenBank accession number (when available) are indicated in each node. The identity of each taxa is colour-coded according to the species.

Fig. 7. Maximum parsimony network of the COI gene 551 bp fragment. Coloured and black circles correspond to a species genotype or a hypothetical genotype, respectively. The size of each circle is proportional to the number of individuals sharing that genotype. The identity of each taxa is colour-coded according to the species.

Description

Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. (Figs 3–5)

Spirocerca lupi (Segovia et al. Reference Segovia2001; Sanchis-Monsonís, Reference Sanchis-Monsonís2015).

Characteristics of adult stage: red when freshly collected. Cylindrical body with tapered ends and maximum width around the location of half of the body length. Cuticle 12 µm thick with narrow striations separated approximately 3 µm. The anterior part is similar in both sexes with a hexagonal opening and six lip-like crescents in the mouth located in the lateral and submedian positions, and a highly sclerotized buccal capsule, rectangular and delimited at the end by the muscular oesophagus. Six triangular teeth-like structures arise from the buccal capsule to the mouth opening in front of each lip. Four wart-shaped cephalic papillae aligned with ventral and dorsal teeth. Two amphids aligned with two lateral teeth below the mouth opening. Ventral and dorsal borders of the mouth opening protrude. Oesophagus divided into an anterior muscular and almost cylindrical oesophagus, and a posterior glandular oesophagus increasing in width until the oesophageal–intestinal junction. Nerve ring located at the second third of the muscular oesophagus and excretory pore and deirid near the junction of both oesophagi.

Female

The description is based on the measurement of 11 female adults. Table 1 summarizes the average, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values of each structure measurement. Body 6.335 ± 1.266 cm long and 1.11 ± 0.185 mm wide. Buccal capsule 98 ± 21 µm long and 171 ± 9 µm wide with 6.643 ± 0.652 µm long teeth. The total length of the oesophagus is 6.585 ± 0.386 mm, with a muscular oesophagus length of 0.416 ± 0.046 mm and a glandular oesophagus length of 6.175 ± 0.420, with a ratio of the glandular–muscular oesophagus of 15.4 ± 3.0. The percentage of the oesophagus to the total body length is 9.9 ± 0.7%. Distance of nerve ring, excretory pore and vulva opening to the anterior end of 0.560 ± 0.045, 0.608 ± 0.061 and 9.772 ± 1.216 mm, respectively. A coiled uterus is present throughout the body until the anterior end. Thick-layered eggs 35 ± 5 µm long and 12 ± 4 µm wide with progressive embryonic development from the posterior end of the worm to the anterior part until reaching the vagina. A tubular-shaped vagina is projected to the outside with a simple vulva opening of 9.772 ± 1.216 mm from the anterior end. The posterior end of the body is slightly curved and culminates with a tip and terminal papillae. A slit-like anus is found 0.308 ± 0.054 mm from the posterior end.

Male

Description of males is based on the measurements of 10 adults. Table 2 summarizes the average, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values of each structure measurement. Body 3.963 ± 0.537 cm long and 0.690 ± 0.090 mm wide. Buccal capsule 0.081 ± 0.016 mm long and 0.148 ± 0.009 mm wide with six teeth-like structures 7.758 ± 2.083 µm long. The total oesophagus length is 4.048 ± 0.240 mm, 11.2 ± 1.76% of the total body length, with a muscular oesophagus length of 0.446 ± 0.026 mm and a glandular oesophagus length of 3.609 ± 0.216 mm. The glandular–muscular oesophagus ratio is 8.3 ± 0.5. The distances of the nerve ring and excretory pore to the anterior end are 0.443 ± 0.069 and 0.536 ± 0.083 mm, respectively.

The posterior end is ventrally curved, with copulatory organs. There are short and parallel longitudinal cuticular ridges ending in a scale-like shape, present in all posterior and ventral parts of the body, and absent in the areas around the cloaca and the tip. Narrow caudal alae and two sets of four pre-anal, nipple-shaped and pedunculated papillae disposed ventrolaterally. The distances between pre-anal papillae 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4 are 42.75 ± 4.68, 66.67 ± 4.03 and 58.39 ± 4.54 µm, respectively. There are two pairs of nipple-shaped post-anal papillae smaller in size than pre-anal papillae, 49.46 ± 2.96 µm apart and not equidistant from the lateral body border. Four pairs of minute nipple-shaped terminal papillae are irregularly disposed in the tip of the posterior end. The cloaca is 0.405 ± 0.073 mm from the posterior end, with a submedian and ward-like cloacal papilla. Two spicules unequal in length and shape, with greater spicules being 2.364 ± 0.166 mm long and needle shaped; and minor spicules 0.566 ± 0.058 mm in length with a distal portion broader and rounder than the base. Irregularly shaped gubernaculum positioned 0.067 ± 0.013 mm from the posterior end.

Type specimens: a holotype of an adult male and three paratypes of two adult females and one male were deposited in the National Natural History Collection of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, with catalogue numbers HUJINVNEM500 for the holotype and HUJINVNEM501, HUJINVNEM502 and HUJINVNEM503 for the paratypes.

Type host: Vulpes vulpes (Carnivora: Canidae); collected between April 2010 and October 2012.

Site in host: Nodules in the stomach wall protruding to the gastric lumen and serosa.

Holotype locality: the holotype specimen was collected from Cortes de Pallás (GPS coordinates X: 672.933, Y: 4.342.786), Valencia, Spain.

Paratype localities: Vall de Gallinera (GPS coordinates X: 738.912, Y: 4.301.914), Alicante, Spain; Jarafuel (GPS coordinates X: 673.417, Y: 4.337.963), Valencia, Spain; Cabanes (GPS coordinates X: 762.082, Y: 4.449.285), Castellón, Spain.

Other localities: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Basilicata region of Italy.

Name of collector: Gloria Sanchis-Monsonís.

Prevalence: 22.03% prevalence in 286 red fox carcasses in the Valencian region from Spain (Sanchis-Monsonís, Reference Sanchis-Monsonís2015).

Other material: DNA samples from all specimens are stored in the Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

Representative DNA sequences: representative 18S rRNA and COI sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MG957119 to MG957121 and MG957122 to MG957144, respectively.

Etymology: the species name is given after the Latin name of its type host V. Vulpes (Lat. genitive singular vulpis ‘of a fox’).

Remarks: Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. shares morphological similarities with S. lupi (Rudolphi, Reference Rudolphi1819) (Tables 1 and 2). However, these species can be distinguished according to the following distinctive criteria: (i) S. vulpis sp. nov. has six triangular teeth-like structures that emerge from the buccal capsule and project anteriorly to the mouth opening. These teeth can be observed by SEM, but also in cleared nematodes by light microscopy. In contrast, S. lupi lacks these structures. (ii) The ratio between the glandular oesophagus and muscular oesophagus lengths is higher in S. vulpis sp. nov females compared with S. lupi females, being 15.41 ± 3.01 and 9.60 ± 2.21, respectively. (iii) The distance from the vulva opening to the anterior end in S. vulpis sp. nov. (9.772 ± 1.216 mm) is much longer compared with S. lupi (2.036 ± 0.847 mm). (iv) The total oesophagus length and the glandular oesophagus length of S. vulpis sp. nov. males (4.05 ± 0.24 and 3.61 ± 0.22 mm) are shorter than those distances in S. lupi males (7.08 ± 0.47 and 6.53 ± 0.41 mm). Therefore, the ratio of the glandular-to-muscular oesophagus length is larger in S. lupi (12.4 ± 2.8) compared with S. vulpis sp. nov. (8.2 ± 0.5). Also, the percentage of the oesophagus length respective to the total body length is 11.15 ± 1.76% in S. vulpis sp. nov. and 20.16 ± 2.8% in S. lupi. (v) Molecularly, both species can be distinguished by their COI sequences, since they have a nucleotide pairwise distance >9%.

Cylicospirura arctica (Petrow, 1927) (syn. S. arctica) is another red-coloured nematode from the Spirocercidae family that possess six triangular-shaped teeth (Clark, Reference Clark1981). This species can be differentiated from S. vulpis sp. nov. by the total body length in females and males (S. vulpis sp. nov.: 6.3 and 4.0 cm, respectively; C. arctica: 9.5–12.5 and 6.2–6.8 mm, respectively) and the position of the vulva in females, which is anteriorly located in S. vulpis sp. nov. and medially positioned in C. arctica.

Discussion

The data presented herein indicate that S. vulpis sp. nov. is a helminth species parasitizing the stomach and the omentum of red foxes, which clearly differs from S. lupi by morphological and molecular characteristics. While studying the life cycle, genetic characterization and molecular diagnosis of S. lupi (Rojas et al. Reference Rojas2017a, Reference Rojas2017b) and collecting samples from carnivores in different areas in the world where this helminth is present, we realized that specimens originating from red foxes are different morphologically and genetically from those described from domestic dogs. These observational data were strengthened by a previous report of Spirocerca sp. in the stomach nodules of red foxes from Denmark and the genetic characterization of these specimens, which suggested the presence of a distinct Spirocerca sp. that has similarities to S. lupi (Al-Sabi et al. Reference Al-Sabi2014). This led to morphometric and phylogenetic analyses to compare Spirocerca sp. specimens obtained from red foxes with those of S. lupi collected from dogs. Our observations led to the proposal of a novel member of this genus, named S. vulpis sp. nov., a parasite of red foxes.

The evidence for separation of S. vulpis sp. nov. from S. lupi and other Spirocercidae species is based on a combination of morphological traits, genetic characteristics and the main location of the adult worm in the host (i.e. the stomach wall vs the oesophagus). A main morphological difference between both Spirocerca spp. is the presence of triangular teeth-like structures present in the buccal capsule evident by SEM and light microscopy in S. vulpis sp. nov. The absence of teeth in S. lupi was confirmed by SEM in six S. lupi adults collected from Israel and agrees with the previous observations on S. lupi from dogs from Iran (Naem, Reference Naem2004). Interestingly, in an early study, Goyanes-Alvarez (Reference Goyanes Alvarez1937) observed what was termed odontoid formations in some S. lupi specimens collected from dogs in Spain. However, it is not specified whether these formations stand for teeth or other sclerotized structures. Perhaps the use of more sensitive imaging equipment, which were not available in 1937 when this report was made, could have obtained a better resolution. More recently, teeth structures were detected by SEM of Spirocerca worms collected also from the stomach nodules of red foxes of Portugal (Segovia et al. Reference Segovia2001). However, the latter study identified these specimens as S. lupi. Thus, it is possible that these S. lupi specimens with teeth-like structures could represent S. vulpis sp. nov. Nevertheless, a molecular analysis would be needed to confirm this.

The morphological differentiation between S. vulpis sp. nov. and S. lupi was also quantified and confirmed by structure measurements of the specimens. We found differences in the total oesophagus and glandular oesophagus lengths in males and in the distance of the vulva opening to the anterior end in females, as well as the ratios and percentages derived from the oesophagus lengths in both sexes. In regard to the difference in the total oesophagus and glandular oesophagus length observed in males, Segovia et al. (Reference Segovia2001) reported that S. lupi males obtained from red foxes of Portugal had a mean length of 4.9 and 4.4 mm, respectively, which are only 0.9 mm larger for both measurements than S. vulpis sp. nov., and 2.2 and 2.1 mm, respectively, smaller than S. lupi. The difference in the measurements between the report of Segovia et al. (Reference Segovia2001) and S. vulpis sp. nov. might rely on the use of different measuring techniques, imaging equipment or software, as well as the conditions in which the worms were kept. Moreover, to our knowledge, the distance of the vulva opening to the anterior end in S. lupi females has not been measured in other studies. However, it is an important and widely studied character in the development of female nematodes, which has been shown to be associated with the phylogenetic placement of species (Kiontke et al. Reference Kiontke2007).

Traditional taxonomic keys classify specimens from the Spirocercidae family into the genus Cylicospirura if teeth in the buccal cavity are present (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson2009), and those without them are classified in the genus Spirocerca (Chabaud, Reference Chabaud1959). Thus, S. vulpis sp. nov. could be misclassified as Cylicospirura sp., if morphology-based keys are used alone. However, these keys have proven to be inconclusive for the taxonomic classification of members of the Spirocercidae family regarding other characters such as median lobes (Chabaud, Reference Chabaud1959) and vulva position (Clark, Reference Clark1981) and indicate that the presence of teeth in the buccal cavity might not be a good character to delineate the two genera. Briefly, Chabaud (Reference Chabaud1959) implied that some features are not known in some congeners by stating that ‘if the genus is reduced to species that lack teeth in the buccal capsule, only the species type S. lupi, and S. vigisiana (Kadenazii, 1946) will remain in the group (…), however, since the author (describing S. vigisiana) didn't provide drawings of the apical view it is impossible to know if there are median lobes’. To date, no further publications on S. vigisiana are available. Therefore, it is unknown if all members of the genus Spirocerca lack teeth or have median lobes and if these traits should determine the genus placement. In addition, Clark (Reference Clark1981) previously stated that not all Cylicospirura spp. have the vulva in the same positions as these keys point out. Furthermore, he described Cylicospirura advena, a nematode from a feral cat in New Zealand without any teeth-like structures in the buccal capsule. In addition, our study demonstrates by phylogenetic comparisons of mitochondrial and nuclear gene loci that Cylicospirura spp. are paraphyletic to Spirocerca spp. and that S. vulpis sp. nov. and S. lupi indeed represent monophyletic sister groups according to the ML and BI phylograms of the COI gene. Therefore, since morphology characters in this family can be misleading for taxonomic classification, we consider that the new species described herein belongs to the genus Spirocerca based on molecular evidence. Discrepancies in taxonomic classification of organisms, when using morphological characters and molecular analyses, have become more common with the incorporation of DNA sequences during species description. In these cases, phylogenetic studies classify organisms differently to morphology-based keys, as observed for Discocriconemella inarata, a nematode of a rhizomatous perennial herb (Powers et al. Reference Powers2010), and the plant parasitic nematodes of the genera Pratylenchus (Janssen et al. Reference Janssen2017) and Xiphinema (Palomares-Rius et al. Reference Palomares-Rius2017). In these examples, authors have followed the molecular evidence to describe new species and have proposed the careful re-description of type specimens, the incorporation of DNA barcodes in the identification of specimens and suggested not to rely only on morphology. Thus, integrative taxonomy tries to unify evidence from different biological disciplines for species delimitation, reaching a high level of confidence when describing a new species (Dayrat, Reference Dayrat2005).

The use of two different molecular markers for species delimitation (Pérez-Ponce de León and Nadler, Reference Pérez-Ponce de León and Nadler2010) enabled an accurate identification of S. vulpis sp. nov. as a new species. We used three different phylogenetic methods for the COI analysis, which confirmed that S. vulpis sp. nov. clustered together with a Spirocerca sp. from a fox from Denmark with a mean distance of 0.7%, and was separated from S. lupi and Cylicospirura spp. with mean distances 13 and 18 times higher, respectively. The COI is usually employed for phylogenetic studies due to its maternal inheritance and higher evolution rate (Blouin, Reference Blouin2002). The use of this gene has shown to resolve species differences in several groups of nematode parasites such as in filarioids (Ferri et al. Reference Ferri2009). In that case, low nucleotide distances (from 0 to 2%) occurred in the COI gene within the species of filarioids (Ferri et al. Reference Ferri2009), while closely congeneric species exhibited a larger variation (i.e. 8–20%) (Blouin et al. Reference Blouin1998; Blouin, Reference Blouin2002), and differences in species within the same family were up to 27% (Ferri et al. Reference Ferri2009). Our results confirmed that the fox-associated species is a congener of S. lupi and has sufficient nucleotide difference to distinguish it from the species of the genus Cylicospirura (from 10.2 to 14.3%). In addition, it is suggested that the worms characterized from Denmark could in fact belong to S. vulpis sp. nov. In contrast, as the 18S rRNA gene has a slower rate of variation, it has been used to reconstruct the phylogenetic history of nematode clades (Blaxter et al. Reference Blaxter1998). Despite the expected lower variation in this locus, both Spirocerca spp. could be distinguished from each other in five nucleotide positions. However, the use of the COI is recommended for more accurate species identification.

The main anatomical location of S. vulpis sp. nov in the definitive host (i.e. gastric nodules) differs from the main site of adult S. lupi in dogs which are nodules in the oesophageal wall. However, S. lupi has occasionally been described to a lesser extent in the gastric mucosa (Mazaki-Tovi et al. Reference Mazaki-Tovi2002) and in a plethora of organs in the dog as a consequence of aberrant migrations. The histopathological description of the gastric nodules described herein resembles the early inflammatory non-neoplastic lesions associated with S. lupi (Dvir et al. Reference Dvir, Clift and Williams2010) due to the presence of fibrosis, lymphocytes and plasmatic cells. Additionally, high numbers of eosinophils were observed in most of S. vulpis sp. nov. nodules, as expected for helminth infections (Allen and Maizels, Reference Allen and Maizels2011). In contrast, it has been observed that eosinophil infiltrates are not common in S. lupi nodules, since Dvir et al. (Reference Dvir, Clift and Williams2010) found eosinophilic infiltrates only in three out of 42 non-neoplastic samples, which might have been associated with an early inflammatory stage during nodule formation. The different preferential sites of adult worm localization may reflect an evolutionary differentiated tropism in hosts. However, it is unknown if S. vulpis sp. nov. can additionally infect domestic dogs and other wild canids, since parasites frequently use more than one host species to guarantee their reproductive success (Rózsa et al. Reference Rózsa, Tryjanowski, Vas, Morand, Krasnov and Littlewood2015). If the specimens with odontoid formations found in domestic dogs from Spain (Goyanes Alvarez, Reference Goyanes Alvarez1937) were indeed S. vulpis sp. nov., it would suggest that this new nematode can use both canid species as definitive hosts. If so, epidemiological and clinical implications may arise for the diagnosis of an infection that crosses host species from wildlife to domestic animals.

Spirocerca vulpis sp. nov. described in the present study seems to present an apparent host preference to red foxes, as demonstrated by the finding of this novel species only in this canid, so far. However, future studies may indicate that the species has a wider host range. Host shift may lead to species separation when the flow of infective stages between the primary and secondary hosts stops, and therefore, the parasite may begin to acquire genetic changes that distinguish it from its ancestor (Rózsa et al. Reference Rózsa, Tryjanowski, Vas, Morand, Krasnov and Littlewood2015). Therefore, the transmission of helminths from domestic dogs to wild animals and vice versa can influence the distribution of helminthiases and have a profound effect on the adaptation and speciation within the populations of parasites (Huyse et al. Reference Huyse, Poulin and Théron2005). For instance, of the 51 nematode species known to infect domestic dogs, it has been proposed that only 17 originated from dogs, and 14 of these, including S. lupi, have been found in wild animal species, suggesting parasite spillover (Weinstein and Lafferty, Reference Weinstein and Lafferty2015). Further phylogeographic studies can clarify the origin of Spirocerca spp. in domestic and wild canids, i.e. whether S. vulpis sp. nov. originated from domestic dogs or other wild canid such as the wolf which is the dog's ancestor, and later spread to red foxes, or if it passed to dogs and then evolved in the dog itself to give rise to S. lupi.

In this study, we describe S. vulpis sp. nov. as a morphologically and phylogenetically new parasite of red foxes. In addition, phylogenetic analyses highlight the re-evaluation of the taxonomical keys for the Spirocercidae family for an integrative taxonomical perspective. Further studies will be needed to clarify the life history, biology and possible pathological effects of S. vulpis sp. nov., and whether dung beetles’ species, the intermediate hosts of S. lupi, also act as intermediate hosts for this parasite, or if it has different intermediate hosts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182018000707.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sanjoy Borthakur, Kalyan Sarma, Eran Dvir and Alex Markovics for the provision of adult S. lupi specimens from dogs for DNA analysis.

Financial support

This study was funded by internal resources of Prof. Gad Baneth's laboratory, and a stipend from the University of Costa Rica granted to Alicia Rojas.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.