Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite that can infect all warm-blooded animals, including humans (Dubey, Reference Dubey2016; Tagel et al., Reference Tagel, Lassen, Viltrop and Jokelainen2019). Toxoplasmosis is a cosmopolitan zoonosis, approximately one-third of the world's population is infected with T. gondii, and thus this parasite is one of the best adapted to infect humans. The parasite life cycle is complex and characterized by a sexual phase in the intestinal epithelium of the felines, the definitive hosts (Remington et al., Reference Remington, Klein, Wilson and Baker2011). Other mammals, reptiles, amphibians or birds are intermediate hosts (in which asexual reproduction occurs). In humans, the natural course of infection involves an acute phase, with a remarkable proliferation of tachyzoites that are widespread in body fluids (Torgerson and Mastroiacovo, Reference Torgerson and Mastroiacovo2013; Robert-Gangneux, Reference Robert-Gangneux2014), and a chronic phase, in which the immune system response induces a switch to the bradyzoites forms, which reproduce inside cysts in the host's tissues, especially brain, retina and muscles (Remington et al., Reference Remington, Klein, Wilson and Baker2011).

Although the disease is usually mild in immune-competent individuals, it can be devastating in immunocompromised people and congenitally infected neonates or children (Avelino et al., Reference Avelino, Amaral, Rodrigues, Rassi, Gomes, Costa and Castro2014; Bharti et al., Reference Bharti, McCutchan, Deutsch, Smith, Ellis, Cherner, Woods, Heaton, Grant and Letendre2016; Cuervo et al., Reference Cuervo, Simonetti, Alegre, Sanchez-Salado and Podzamczer2016). Manifestations include encephalitis, blindness or even death. Toxoplasma gondii was originally considered a clonal population composed of three dominant strains, designated I, II and III. Types II and III are predominantly observed in Europe and North America, while in Central and South America, there are abundant non-archetypal genotypes. The genotypic diversity in these regions does not present a dominant lineage, but is related to strains that are more virulent and accompanied by more severe clinical signs (Shwab et al., Reference Shwab, Jiang, Pena, Gennari, Dubey and Su2016; Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Black, Oliveira, Burrells, Bartley, Melo, Chianini, Palarea-Albaladejo, Innes, Kelly and Katzer2019).

Despite the impacts of this disease on human health, the available treatments are still very limited. The recommended toxoplasmosis treatment or prophylaxis is a combination of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine. These drugs can reduce parasite replication, especially during the acute phase of the disease. However, they have severe side-effects, including neutropaenia, decreased in platelet count, leucopaenia, increased serum creatinine and serum liver enzymes, haematological abnormalities and hypersensitivity reactions (Petersen and Schmidt, Reference Petersen and Schmidt2003; Remington et al., Reference Remington, Klein, Wilson and Baker2011). In pregnant women suspected of acute toxoplasmosis, spiramycin is used to avoid placental transmission (Gomella et al., Reference Gomella, Eyal and Zenk2004). For the treatment of ocular manifestations in immunocompetent individuals, clotrimazole (sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim) has often been used with good results and lower side-effects, although it does not eliminate the cysts in the ocular membranes, and does not prevent relapses (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Lin and Lu2018).

In view of the urgent need for new medicines for toxoplasmosis treatment, the search for compounds with different mechanisms of action against T. gondii has been a target for many researchers (El-Zawawy et al., Reference El-Zawawy, El-Said, Mossallam, Ramadan and Younis2015a, Reference El-Zawawy, El-Said, Mossallam, Ramadan and Younis2015b; Montazeri et al., Reference Montazeri, Sharif, Sarvi, Mehrzadi, Ahmadpour and Daryani2017; Murata et al., Reference Murata, Sugi, Weiss and Kato2017). Drugs currently used for other purposes could be tested – alone or in combination – as alternative anti-T. gondii treatments (Shiojiri et al., Reference Shiojiri, Kinai, Teruya, Kikuchi and Oka2019; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Si, Shang, Zhang, Li, Zhou and Zhang2019). Additionally, the in vivo evaluation of new anti-T. gondii compounds is conducted mainly in the acute phase of toxoplasmosis (RH strain) (Montazeri et al., Reference Montazeri, Sharif, Sarvi, Mehrzadi, Ahmadpour and Daryani2017). Identifying drugs with anti-bradyzoites effects, effective in the chronic phase, is a great challenge to researchers. Intriguingly, in vitro and in vivo studies showed that statins, a class of lipid-lowering medications, can reduce T. gondii replication (Li et al., Reference Li, Ramakrishnan, Striepen and Moreno2013, Reference Li, Li, Szajnman, Rodriguez and Moreno2017; Sanfelice et al., Reference Sanfelice, da Silva, Bosqui, Miranda-Sapla, Barbosa, Silva, Ferro, Panagio, Navarro, Bordignon, Conchon-Costa, Pavanelli, Almeida and Costa2017a, Reference Sanfelice, Bosqui, da Silva, Miranda-Sapla, Panagio, Navarro, Conchon-Costa, Pavanelli, Almeida and Costa2018), especially rosuvastatin (Sanfelice et al., Reference Sanfelice, Machado, Bosqui, Miranda-Sapla, Tomiotto-Pellissier, de Alcântara Dalevedo, Ioris, Reis, Panagio, Navarro, Bordignon, Conchon-Costa, Pavanelli, Almeida and Costa2017b). Statins are 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors in humans, but studies suggest that statins can also negatively influence T. gondii isoprenoids biosynthesis (Li et al., Reference Li, Ramakrishnan, Striepen and Moreno2013, Reference Li, Li, Szajnman, Rodriguez and Moreno2017). While these studies demonstrated the anti-proliferative action of statins in T. gondii tachyzoites in vitro, there are no studies about the anti-proliferative action of rosuvastatin in chronic phase in vivo models. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of rosuvastatin in vivo on the pathology of chronic T. gondii infection in mice.

Materials and methods

Study design

Female Swiss mice (25–45 days old) were infected orally (gavage) with 25 T. gondii cysts. The animals were divided into five groups as follows: GI – non-infected and non-treated (negative control); GII – infected and treated with saline (infection control); GIII – infected and treated with pyrimethamine 12.5 mg kg−1 body weight day−1 + sulfadiazine 50 mg kg−1 body weight day−1 (PS treatment) (Franco et al., Reference Franco, Silva, Costa, Gomes, Silva, Pena, Mineo and Ferro2011); GIV – infected and treated with rosuvastatin 10 mg kg−1 body weight day−1 (R10); GV – infected and treated with rosuvastatin 40 mg kg−1 body weight day−1 (R40) (GIV and GV are treatments groups) (Reagan-Shaw et al., Reference Reagan-Shaw, Nihal and Ahmad2008; Neto-Ferreira et al., Reference Neto-Ferreira, Rocha, Souza-Mello, Mandarim-de-Lacerda and De Carvalho2013). Fifty days post-infection, the treatments were initiated for 21 days. The mice were observed daily, and mortality and clinical parameters, including alopecia, erection of hairs, abdominal distension and ascites, were analysed.

In vivo assay

At the end of the treatment period (71 days post-infection), the mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane by the inhalation route. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture, and serology was performed by a microagglutination test at a 1:50 screening dilution of the serum. Part of the serum was used to examine the activity of the liver enzymes aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Subsequently, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the brain, liver, lungs and skeletal muscle (biceps femoris) were collected. The organs were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and divided into two parts. One was frozen for future DNA extraction and the other one was fixed in 10% formalin in PBS at pH 7.2 for 18–24 h, and then transferred and maintained in 70% ethanol until tissue processing.

Activity of AST, ALT and ALP

The AST, ALT and ALP activities were measured in the serum by spectrophotometry (Shimadzu UV-1800) using kinetic methods with commercial kits (AST – PP, ALT – PP and ALP – PP; Gold Analisa®, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

The collected brain, liver, lung and muscle were macerated in saline solution, and the total genomic DNA was extracted from 125 µL sample aliquots using ReliaPrep™ gDNA Tissue Miniprep System (Promega, Madison, USA), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Total DNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, US). qPCR was performed in duplicate with 50 ng of the total extracted DNA using the QuantiNova SYBR™ Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers B1 (B22–B23; forward: 5′-AACGGGCGAGTAGCACCTGAGGAGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-TGGGTCTACGTCGATGGCATGACAAC-3′) were used in order to amplify a 115 base pairs (bp) sequence in T. gondii (Burg et al., Reference Burg, Grover, Pouletty and Boothroyd1989). In each reaction, a negative control (mixture without DNA) and a positive control (DNA extracted from ME-49 strain) were processed. The reaction was performed with a LightCycler 96 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) thermal cycler using reaction conditions recommended by the manufacturer: 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 10 min at 95 °C and 50 cycles at 60 °C for 30 s. For the final analysis, a denaturation curve was performed from 60 to 97 °C, followed by electrophoresis of the products in order to ensure there was no non-specific amplifications or dimers. A standard curve was processed using serially diluted DNA in Milli-Q water (Nanassy et al., Reference Nanassy, Haydock and Reed2007). The DNA quantity (ng) for each sample was deduced from standard curves and then, converted in equivalent parasites (Eq. parasite), according to Jauregui et al. (Reference Jauregui, Higgins, Zarlenga, Dubey and Lunney2001).

Histopathology study

Histopathological analysis was performed in the following organs: brain, liver, lungs, and cardiac and skeletal muscles. Five mice from groups GII, GIII, GIV and GV, and two mice from GI were included in the analysis. The tissues were processed by dehydration and paraffin embedding. Three 5 mm histological sections (non-continuous sequence) from each sample were prepared and stained with Harris haematoxylin and eosin (HE) technique.

The sections were examined with a light microscope (OpticamO500R, Doral, Fl., USA), with the 10, 20, 40 and 100× objectives. The pathological lesions in brain tissue were qualitatively classified for the presence of the following parameters: necrosis (N), hyperaemia (HP), haemorrhage (HM), oedema (E), and inflammation (I) and gliosis (G).

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed statistically with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the results among groups. GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical behaviour and mortality rates

Among the 42 animals included in the study, 35 survived until the end of the experiment (i.e. 71 days post-infection). None of the rosuvastatin-treated-mice (GIV and GV) died. The mortality rate was 42.8% (three mice) in the GIII (infected and treated with PS). The other deaths were one mice in each of the control groups, GI (non-infected and non-treated) and GII (infected and non-treated), representing a mortality rate of 14.3%. In GIII, there were notable clinical alterations in the animals, including fur loss on the muzzle and ears and piloerection. No changes were observed in the clinical aspects of the animals in the other groups. Diarrhoea and abdominal distention were not observed in any groups. Table 1 shows the mean liver and brain weights. The liver weight was increased in GII and GIII mice. GI, IV and V mice showed a lower mean body weight compared with GII (P < 0.05). The weight of the livers from GIV and GV mice was not significantly different compared with GI. The brain weight did not differ significantly among the groups except for GI compared with GII (P < 0.05).

Table 1. Mean brain and liver weight of mice (g).

GI, negative control; GII, infected control; GIII, infected and treated with pyrimethamine + sulfadiazine (12.5 mg + 50 mg kg−1 body weight day−1); GIV, infected and treated with rosuvastatin 10 mg kg−1 body weight day−1; GV, infected and treated with rosuvastatin 40 mg kg−1 body weight day−1.

a Statistically significant compared with GII.

b Statistically significant compared with GIII (ANOVA one way – Tukey's post-test applied, P < 0.05).

Biochemical study

AST, ALT and ALP levels showed a non-significant increase after treatment in GIV and GV mice. In GV, ALT values were lower compared with infected mice (GII) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Serum hepatic enzymes levels in mice chronically infected with the Toxoplasma gondii ME-49 strain, treated and untreated with rosuvastatin. Notes and abbreviations: AST – aspartate transaminase; ALT – alanine transaminase; ALP – alkaline phosphatase; GI – negative control; GII – infected control; GIII – infected and treated with pyrimethamine + sulfadiazine (12.5 + 50 mg kg−1 body weight day−1); GIV – infected and treated with rosuvastatin 10 mg kg−1 body weight day−1; GV – infected and treated with rosuvastatin 40 mg kg−1 body weight day−1; IU/L – international units per litre of blood *Statistically significant (P < 0.05).

qPCR

The brain parasite load was significantly reduced in GV compared with GII and GIV mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, T. gondii DNA was also detected in skeletal muscle, but the parasite load was reduced when compared with the brain. The mean of equivalent parasite in the skeletal muscle was: GII – 25 535; GIII – 6993.86; GIV – 8,672.86 and GV – 715.262 Eqp of T. gondii (P > 0.05). In liver and lungs, the parasite load was not detectable by qPCR.

Fig. 2. Parasite load in brain of mice infected with the Toxoplasma gondii ME49 strain (in equivalent parasites). Notes and abbreviations: GI – negative control; GII – infected control; GIII – infected and treated with pyrimethamine + sulfadiazine (12.5 + 50 mg kg−1 body weight day−1); GIV – infected and treated with rosuvastatin 10 mg kg−1 body weight day−1; GV – infected and treated with rosuvastatin 40 mg kg−1 body weight day−1; ab – Statistically significant (P < 0.05) by one-way ANOVA and the Newman-Keuls multiple comparison post-test.

Histopathological findings

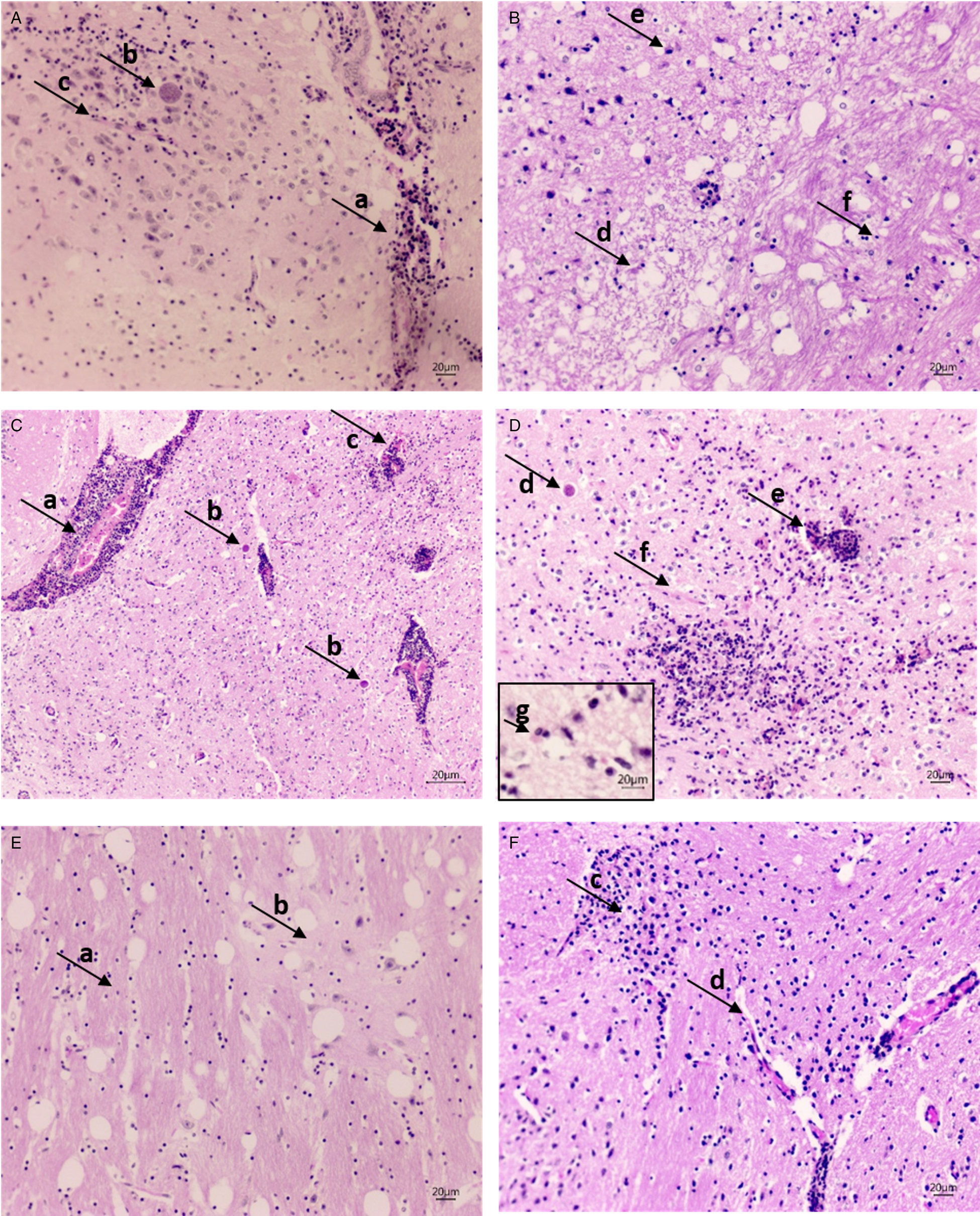

Figure 3 shows HE-stained brain sections from infected groups. The sections exhibited multiple T. gondii cysts in both treated (GIII, GIV and GV) and untreated (GII) animals. Prominent neuropathological changes were observed on day 71 post-infection in GII and GIII mice, including necrosis, inflammatory foci with glial proliferation, hyperaemia, vasculitis with perivascular mononuclear infiltrate and haemorrhage. Glial proliferation and diffuse gliosis were observed throughout the brain (Fig. 3A–D). In contrast, in rosuvastatin-treated mice (GIV and GV), there were cysts along with discrete perivascular infiltrates, hyperaemia and glial focus, but no recent necrosis was observed. However, diffuse glial proliferation with well-established gliosis was present, data that may be indicative of advanced tissue repair (Fig. 3E and F). There were no histopathological findings consistent with chronic T. gondii infection in the lungs, liver and skeletal muscles. In these organs, only non-specific and discrete inflammatory infiltration was observed in some animals. Cysts were not observed in skeletal muscle, even though parasite DNA was detectable in the qPCR analysis of biceps femoris.

Fig. 3. (A and B) Micrographs from GII (positive control) brain. (A) Vasculitis with perivascular infiltrate (arrow, a), bradyzoites inside cysts (arrow, b), lymphomonocytic infiltrate and glial proliferation around, gliosis focus and endothelial proliferation (arrow, c; 20× magnification). (B) Recent necrosis area (arrow, d) with gliosis in progress, gemistocytic astrocyte (arrow, e) contrasted with the area of well-formed gliosis (arrow, f; 20× magnification). (C and D) Micrographs from GIII (PS treated) brain. (C) Intense perivascular infiltrate with vasculitis (arrow, a), bradyzoites within the cysts (arrow, b); inflammatory foci with glial proliferation and diffuse gliosis, vasculitis with haemorrhage (arrow, c; 20× magnification). (D) Inflammatory foci with glial proliferation and diffuse gliosis, bradyzoites within the cysts (arrow, d), vasculitis with haemorrhage (arrow, e), endothelial proliferation (arrow, f; 20× magnification) and a gemistocytic astrocyte (arrow, g; 40× magnification). (E and F) Micrographs from GIV (rosuvastatin 10 mg kg−1) brain. (E) Gliosis (arrow, a) contrasted with normal cortical area and neurons (arrow, b), with evidence of the tissue repair (20× magnification). (F) Micrographs from GV (rosuvastatin 40 mg kg−1) brain. Inflammatory foci with glial proliferation (arrow, c), well-formed gliosis and discreet perivascular infiltrate (arrow, d; 20× magnification).

Discussion

The current study was performed to investigate, for the first time, the in vivo effect of rosuvastatin on T. gondii chronic infection. The results showed that this drug reduced the parasite load in the brain of mice chronically infected (cyst-forming type II) with T. gondii. Our results are similar to Sanfelice et al. (Reference Sanfelice, Machado, Bosqui, Miranda-Sapla, Tomiotto-Pellissier, de Alcântara Dalevedo, Ioris, Reis, Panagio, Navarro, Bordignon, Conchon-Costa, Pavanelli, Almeida and Costa2017b), who demonstrated the in vitro anti-proliferative effect of rosuvastatin against T. gondii tachyzoites (RH strain). In that study, the authors observed a 37 and 27% reduction in the number of infected cells after 50 and 25 mg mL−1 of rosuvastatin treatment, respectively, when compared with the negative control.

Rosuvastatin is a drug widely used to reduce the serological levels of cholesterol and is well-tolerated by the majority of patients. In this study, 40 mg kg−1 day−1 rosuvastatin reduced the DNA quantity in mice brain. It was also well tolerated because the treated animals did not present clinical signs, such as mortality or biochemistry alterations related to toxicity. The treatments were initiated on day 50 post-infection, a time when the chronic phase was well established. The usual rosuvastatin dose for treating humans with high blood cholesterol levels is 10 mg day−1 (Reagan-Shaw et al., Reference Reagan-Shaw, Nihal and Ahmad2008; Neto-Ferreira et al., Reference Neto-Ferreira, Rocha, Souza-Mello, Mandarim-de-Lacerda and De Carvalho2013). The highest rosuvastatin dose (40 mg kg−1 day−1) was utilized to verify the main effects of this drug in rodents because they present a more accelerated metabolism compared to humans. Hence, a higher dose is required for them to respond to the same extent as humans treated with a lower one (Fraulob et al., Reference Fraulob, Souza-Mello, Aguila and Mandarim-de-Lacerda2012; Neto-Ferreira et al., Reference Neto-Ferreira, Rocha, Souza-Mello, Mandarim-de-Lacerda and De Carvalho2013). Of note, the highest rosuvastatin doses showed beneficial effects in our chronic toxoplasmosis in vivo model.

In this study, the reduction of parasite load in the rosuvastatin-treated mice brain indicates that the drug penetrated the blood–brain barrier and interfered with cysts growth. Statins affect isoprenoids, lipid compounds that have myriad crucial functions. They are essential for parasite metabolism and are synthetized in apicoplasts through the 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate (DOXP) pathway. Toxoplasma gondii can salvage some isoprenoid intermediates from the host while depending on its own synthetic machinery for others (Li et al., Reference Li, Ramakrishnan, Striepen and Moreno2013).

There was an increase in the brain and liver weights during T. gondii chronic infection in all infected groups, but comparatively the weights of these organs in the rosuvastatin-treated groups were most similar to uninfected mice. These results may be attributed to the potential of rosuvastatin to reduce the cerebral parasitic load and controlling the inflammatory process. The increased brain weight may be attributed to the inflammatory reaction and driven by pro-inflammatory cytokines and the consequent accumulation of inflammatory cells (Gulinello et al., Reference Gulinello, Acquarone, Kim, Spray, Barbosa, Sellers, Tanowitz and Weiss2010). Furthermore, we observed this effect in the histopathological analyses. The levels of the hepatic enzymes AST, ALT and ALP were increased in GII and GIII and decreased in GIV and GV mice. In GV, ALT values were lower when compared with infected mice (GII). The lower liver weight and reduced hepatic enzymes levels in rosuvastatin-treated groups may be attributed to the cytoprotective actions of this compound. Toxoplasma gondii infection is implicated in causing abnormal liver function tests in mice, including ALT and AST, 6 days after infection (Mordue et al., Reference Mordue, Monroy, La Regina, Dinarello and Sibley2001).

This study showed that in rosuvastatin-treated GIV and GV mice, cysts were present, but discrete perivascular infiltrates and glial proliferation were observed, especially in GV. In GII and GIII brain, besides cysts, necrosis, inflammatory foci with glial proliferation, hyperaemia, vasculitis with abundant perivascular infiltrate and haemorrhage were observed. Glial proliferation and gliosis were observed throughout the brain. These alterations demonstrated that the active inflammatory process was present even in the chronic phase of infection (71 days). The presence of inflammatory infiltrate can contribute to the tissue lesion through oxidative stress and the perivascular infiltrate can modulate necrosis. According to Dincel and Atmaca (Reference Dincel and Atmaca2016) and Dincel (Reference Dincel2017), T. gondii infection can promote marked pathological processes in the brain, potentially via oxidative stress, high levels of nitric oxide production, glial activation and apoptosis.

Necrosis and tissue damage were attenuated in the rosuvastatin-treated mice. In GV, there were areas of gliosis, without neurons, data that indicate previous necrosis was in the process of resolution. In this group, there was a less prominent perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, in both GIV and GV brain, recent necrosis was absent, unlike in GII and GIII animals. However, glial proliferation was present, evidence of advanced tissue repair process. Thus, we infer that rosuvastatin can influence the host's response to the T. gondii ME-49 strain in a chronic brain infection, possibly by modulating the inflammatory level and decreasing tissue injury. Other studies demonstrated that statins attenuate damage that results in the cerebral inflammatory response after stroke. Rosuvastatin contributes to preventing reperfusion damage in mice with brain ischemia by reducing glial cell activation (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Shen, Mai, Zang, Liu, Tsang, Li and Xu2019). Cho et al. (Reference Cho, Jang, Park and Heo2019) showed that statins presented anti-inflammatory activity by tumour necrosis factor suppression. Additionally, the neuropathology in T. gondii-infected mice is reduced by the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs that blocked cyclooxygenase-2 and thus modulate the inflammatory response (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Silva, Franco, de Oliveira Gomes, Souza, Milian, Ribeiro, Rosini, Guirelli, Ramos, Mineo, Mineo, Silva, Ferro and Barbosa2019).

Notably, the currently available chemotherapy for toxoplasmosis presents low effectiveness in the chronic phase of infection, with no activity against bradyzoites inside tissue cysts (Murata et al., Reference Murata, Sugi, Weiss and Kato2017; Montazeri et al., Reference Montazeri, Mehrzadi, Sharif, Sarvi, Shahdin and Daryani2018). Most published studies that evaluate new compounds against T. gondii were developed during the acute phase of infection (Montazeri et al., Reference Montazeri, Sharif, Sarvi, Mehrzadi, Ahmadpour and Daryani2017). There is an urgent need to develop new anti-Toxoplasma agents that are both efficacious and non-toxic to humans, considering that the drugs available are still limited to the elimination of the parasite in the acute phase of the disease and promote important side-effects (Montazeri et al., Reference Montazeri, Sharif, Sarvi, Mehrzadi, Ahmadpour and Daryani2017, Reference Montazeri, Mehrzadi, Sharif, Sarvi, Shahdin and Daryani2018; Murata et al., Reference Murata, Sugi, Weiss and Kato2017). Thus, our findings indicate the therapeutic potential of rosuvastatin in cystic forms of T. gondii. However, further studies are necessary in order to investigate the effect of statins in the physiopathology of chronic toxoplasmosis infection and the interaction of such compounds with the host inflammatory response.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that rosuvastatin, mainly at a dose of 40 mg kg−1 body weight day−1, reduced cerebral parasite load in mice infected with the T. gondii ME-49 strain during the chronic phase of infection, with no clinical or biochemical alterations. The drug penetrated the blood–brain barrier, interfered with bradyzoites and influenced inflammatory foci by reducing the perivascular infiltrate and glial proliferation. These findings suggest that rosuvastatin can be considered a promising alternative composite in the treatment of toxoplasmosis, mainly in the chronic phase of infection.

Studies are necessary to investigate the effect of statins in the physiopathology of chronic toxoplasmosis infection and the interaction of such compounds with the host inflammatory response.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Jurandir Fernando Comar for helping us in the analysis of hepatic enzymes.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Fundação Araucária (grant number 220-2014).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This study was performed following the recommendations of institutional guidelines for animal ethics, Comissão de Ética na Utilização de Animais (CEUA-UEM). All procedures were approved and conducted according to the institutional guidelines for animal ethics (Approval N° 5654290317).