Introduction

Toxoplasmosis is a worldwide zoonosis caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, which was first discovered in 1908 in the rodent Ctenodactylus gundi at the Pasteur Institute in Tunisia (Nicolle and Manceaux, Reference Nicolle and Manceaux1908). At the same time, the parasite was noted in the domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) from Brazil (Splendore, Reference Splendore1908). Cats (domestic and wild) are the only definitive hosts of T. gondii and are essential in its epidemiology because they are the only hosts that can shed environmentally resistant oocysts (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010).

Approximately one-third of humanity is infected with T. gondii worldwide although this varies markedly between populations (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010; Robert-Gangneux and Dardè, Reference Robert-Gangneux and Dardé2012). Most infections appear to be asymptomatic in immunocompetent persons; however, the parasite can cause serious disease in unborn fetus and immunocompromised individuals (Peyron et al., Reference Peyron, Wallon, Kieffer, Graweg, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2016). In many animal host species, the infection is also typically subclinical; however, toxoplasmosis can be fatal in many hosts (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010).

Here, we review the detailed prevalence, epidemiological aspects and clinical disease of natural T. gondii infection in humans and animals, with focus on domestic animals, from Egypt.

Methods for present review

Egypt is a large African country and has a human population >100 million. It is divided into 27 governorates (Fig. 1). The largest city in Egypt is Cairo, the capital, with a population of >8 million people. Nearly 57% of people live in rural areas, whereas 43% live in urbanized cities (World Population Review, 2019). The Egyptian economy is variable and depends largely on agriculture.

Fig. 1. Map of Egypt including 27 governorates. (1) Matrouh; (2) Alexandria; (3) Beheira; (4) Kafr ElSheikh; (5) Dakahlia; (6) Damietta; (7) Port Said; (8) North Sinai; (9) Gharbia; (10) Menoufiya; (11) Kalubiya; (12) Sharkia; (13) Ismailia; (14) Giza; (15) Fayoum; (16) Cairo; (17) Suez; (18) South Sinai; (19) Beni Suef; (20) Minia; (21) El Wady El Gadeed; (22) Assiut; (23) Red Sea; (24) Sohag; (25) Qena; (26) Luxor; (27) Aswan.

A systematic electronic search of published data was conducted from November 2018 to May 2019. Different databases were consulted including PubMed, Science Direct and Google Scholar using the following keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, toxoplasmosis, Egypt, human and animals. Websites of the local Egyptian journals were also incorporated in our search. Libraries of different Egyptian medical and veterinary faculties and institutes were consulted for the old published papers, which are not available as electronic files. Full texts of some earlier published papers were available in the collection of one of us (JPD).

We found numerous reports (>250) on toxoplasmosis in humans and animals from Egypt. Criteria for inclusion were the full text of papers, abstracts only were excluded. After filtering the collected studies, 170 articles met the criteria to be selected for this review. No statistical methods were employed in this study. In the present review, we attempted to incorporate all published reports available to us on natural T. gondii infections in Egypt. Some reports of toxoplasmosis in Egypt were included in two reviews on T. gondii infections in Africa (Tonouhewa et al., Reference Tonouhewa, Akpo, Sessou, Adoligbe, Yessinou, Hounmanou, Assogba, Youssao and Farougou2017; Rouatbi et al., Reference Rouatbi, Amairia, Amdouni, Boussaadoun, Ayadi, Al-Hosary, Rekik, Ben Abdallah, Aoun, Darghouth, Wieland and Gharbi2019). The present review is limited to Egypt.

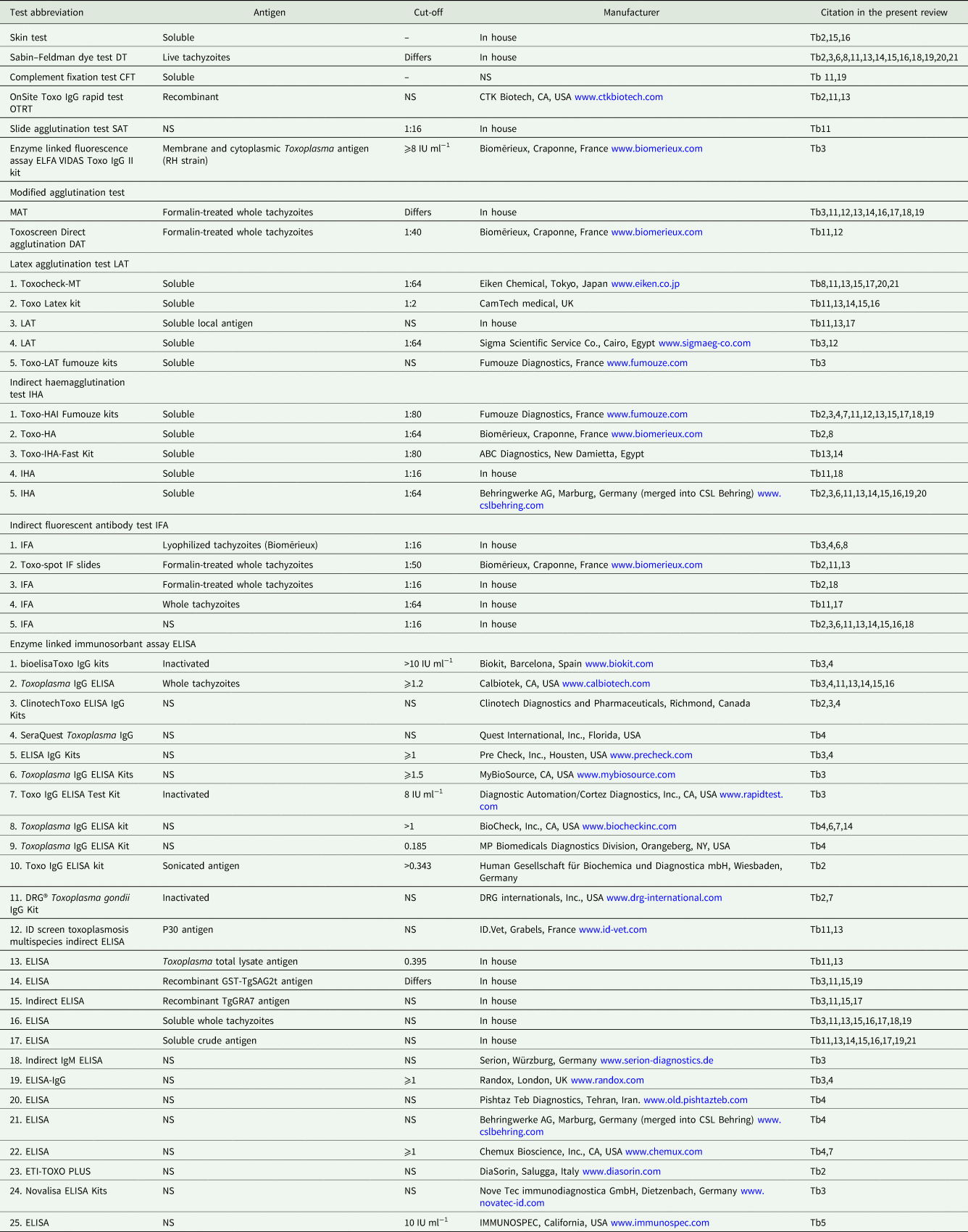

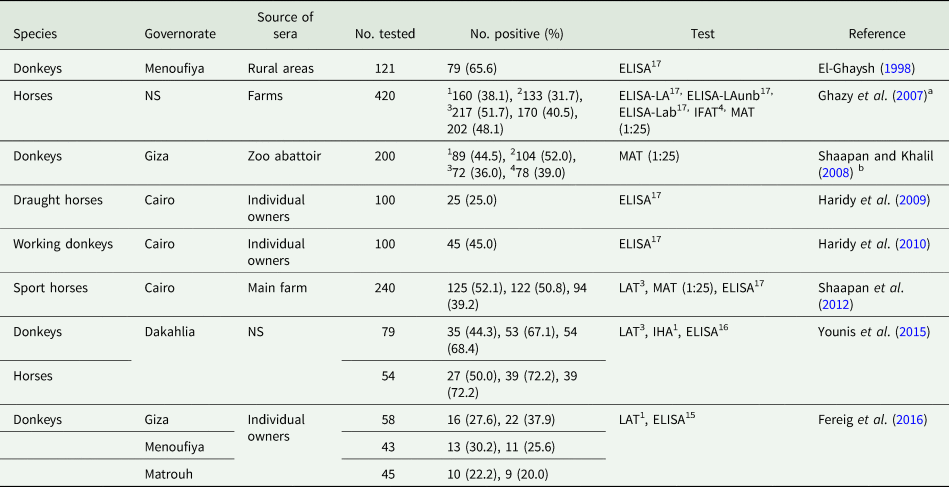

In the present review, detailed serological, parasitological and clinical information on T. gondii infections in humans and animals is summarized in the tables and throughout the text. Different serological techniques used in the Egyptian studies are listed in Table 1. Cut-off values for serological tests are listed wherever the authors provided the information. Superscripts in the tables refer to the details of the serological tests provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Details of serological tests used for the detection of T. gondii antibodies in animals and humans in Egypt

Tb, table.

History of toxoplasmosis in Egypt

Rifaat and Nagaty (Reference Rifaat and Nagaty1959) first reported dermal hypersensitivity to T. gondii in 15.6% of 334 hospital patients and technical personnel from Cairo using the T. gondii skin test. The skin test was one of the first tests developed by Frenkel (Reference Frenkel1948) for a population survey for T. gondii in California, USA; it is a very insensitive test and does not detect acute infection. Subsequently, a highly sensitive and specific test, the dye test (DT), was invented by Sabin and Feldman for the detection of antibodies to T. gondii. Beginning in 1962, Rifaat et al. used the DT to conduct serological surveys for antibodies to T. gondii in humans and other hosts in Egypt. The DT requires the use of live T. gondii and is used now only in few laboratories in the world. Rifaat et al. (Reference Rifaat, Wishahy, Sadek, Elkhalek and Munir1973e) also reported the first case of congenital toxoplasmosis, and they were the first to isolate viable T. gondii in Egypt (Rifaat et al., Reference Rifaat, Mahdi, Arafa, Nasr and Sadek1971, Reference Rifaat, Sadek and Elazghal1973a, Reference Rifaat, Hanna, Abdallah, Moch and Botros1973c, Reference Rifaat, Salem, Sadek, Azab, Abdel-Ghaffar and Abdel-Baki1976b, Reference Rifaat, Arafa, Sadek, Nasr, Azab, Mahmoud and Khalil1976c). Currently, there is no central laboratory or group of researchers actively investigating toxoplasmosis in humans or animals, and unfortunately, no studies are available on the awareness of physicians in Egypt about toxoplasmosis.

Toxoplasmosis in humans

Serological prevalence in general population

In Egypt, there are no centralized data on the national prevalence of T. gondii. Most serological reports are based on convenience samples, including in pregnant women, and patients with disorders (Tables 2–5). Generally, little is known of T. gondii infection from Sinai and Red Sea governorates, although habits of people living there promote T. gondii transmission. Most people living there are Bedouins working mainly in livestock rearing. They usually eat undercooked mutton and drink raw goat and camel milk, in addition to the critical deficiency in hygienic measures and health services. Isolated serological reports in the general population and occupational groups are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in general human population from Egypt

yrs, year; Ab, antibody.

a Now known as Beheira governorate.

Notable among these early surveys is the 16.3% prevalence determined by the DT (Rifaat et al., Reference Rifaat, Salem, Khalil, Khaled, Sadek, Azab and Hanna1975). Higher seroprevalence is reported in emigrants (37.5%) and abattoir workers (30.9%) compared with 24.4% in hospital attendants (Maronpot and Botros, Reference Maronpot and Botros1972). More recently, a very high (33–67%) seroprevalence was reported among blood donors (Table 2). Additionally, T. gondii DNA was found in 10% (15/150) of blood donors from Alexandria (El-Geddawi et al., Reference El-Geddawi, El-Sayad, Sadek, Hussien and Ahmed2018); of them, nine were IgG seropositive and six were seronegative (no IgM testing was done). Toxoplasma gondii DNA was also noted in 6% (18/300) of blood donors from Kalubiya governorate. Of them, eight were IgM seropositive (El-Sayed et al., Reference El-Sayed, Abdel-Wahabl, Kishik and Alhusseini2016a). Authors proposed the acute infection and probability of T. gondii transmission during blood transfusion. This is a very high rate of T. gondii DNA in the blood of asymptomatic individuals. Caution is needed that the accuracy of PCR assay could affect the results. In addition, no further testing was conducted for the positive cases.

Little is known of T. gondii prevalence in children in Egypt. Rifaat et al. (Reference Rifaat, Schafia, Salem, Morsy and Khalid1963) tested 356 school children from El Wady El Gadeed governorate using the skin test. Samples were collected from children ⩾12 years. Nine (2.5%) children were positive. In a recent report, T. gondii antibodies were found in 13 (2.9%) of 6–16 years old 1615 school children (Bayoumy et al., Reference Bayoumy, Ibrahim, Abou El Nour and Said2016). In these two studies, there is no distinction between acquired infection in childhood and congenital infection.

Data on convenience samples in pregnant women from Egypt attending private health clinics are shown in Table 3. Screening sera for toxoplasmosis is routinely done for pregnant women in Egypt. Unfortunately, this screening is conducted mostly in private diagnostic laboratories, which have no systems for archiving the results. In addition, results of this screening are not conclusive because it is based upon the commercially available tests without efficiency verification. Many published reports on toxoplasmosis in pregnant women from Egypt are of limited sample size and have insufficient information on the studied populations. Results are not comparable among different reports because of sample size, diagnostic test used and living conditions of the women tested. There are few data on seroconversion during pregnancy and before pregnancy.

Table 3. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in pregnant women tested in hospitals or private clinics in Egypt

MFTR, maternal fetal transmission rate; OGHA, obstetrics and gynaecology hospitals attendants; Ab, antibody; yrs, years.

a Including some lymphadenopathy, fever and malaise cases, but the authors did not specify numbers of different cases.

b Risk assessment, see Table 6.

Table 4. Diagnosis of T. gondii associated abortion, complicated pregnancy and congenital infection in women from Egypt

Ab, antibody; ND, not done; NS, not stated; IUFD, intrauterine fetal death; CMF, congenital malformation.

Numbers in parenthesis are percentages.

a Risk assessment, see Table 6.

b DNA in the placenta.

Table 5. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in patients with several disorders

ND, not done; NS, not stated; mo, month; yr, year.

a Pathogenic bacteria were excluded.

Risk factors associated with T. gondii infection

Generally, risk factors of T. gondii infection in humans were discussed by many authors (Table 6). Infections were associated with factors such as contact with cats, contact with soil, residence (rural or urban), socioeconomic standards, educational level, ingestion of ready to eat meat products, consumption of undercooked mutton, consumption of raw vegetables, drinking raw milk and consumption of locally prepared Kareish cheese (Elsheikha et al., Reference Elsheikha, Azab, Abousamra, Rahbar, Elghannam and Raafat2009; El Deeb et al., Reference El Deeb, Salah-Eldin, Khodeer and Allah2012; Nassef et al., Reference Nassef, Abd El-Ghaffar, El-Nahas, Hassanain, Shams El-Din and Ammar2015; Hussein et al., Reference Hussein, Elshemy, Abd El-Mawgod and Mohammed2017). Reports from occupational workers (Table 2) particularly butchers illustrated high T. gondii seroprevalence (Abou-Elenin et al., Reference Abou-Elenin, Abdel-Wahab, El-Bestar and Abdel-Aal1983; El-Ridi et al., Reference El-Ridi, Nada, Aly, Habeeb and Aboul-Fattah1990; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Salama, Gawish and Haridy1997). In addition, T. gondii antibodies were found in the sera of 48 (37.7%) of 127 workers in pig farms from Cairo and Kalubiya where pigs were raised completely on garbage feeding. Of them, 15 had high (1:512–1:1024) antibody titres (Barakat et al., Reference Barakat, El Fadaly, Shaapan and Khalil2011). Toxoplasma gondii DNA was found in 17 (35.4%) out of 48 seropositive occupational workers; however, the authors did not specify their professions (Hassanain et al., Reference Hassanain, El-Fadaly, Hassanain, Shaapan, Barakat and Abd El Razik2013). It seems that they tested the same sera used in Barakat et al. (Reference Barakat, El Fadaly, Shaapan and Khalil2011).

Table 6. Risk factors of T. gondii seroprevalence in human population in Egypt

Data linking association between T. gondii infection and several disorders such as chronic liver disease and other conditions were too few for a cause–effect relationship (Table 5).

Clinical toxoplasmosis

Congenital

The first report of a congenital toxoplasmosis-like illness in Egypt was in a 1.5-year-old child from Giza (Rifaat et al., Reference Rifaat, Wishahy, Sadek, Elkhalek and Munir1973e). He was admitted to the hospital presenting with marasmus and a mass in the upper part of the abdomen of 1 year's duration. The abdominal examination revealed enlarged liver without ascites or lymph node enlargement. Skull radiography showed microcephaly and bilateral 1–3 mm wide calcification. An extensive central chorio-retinal lesion was also found. The child had a DT T. gondii antibody titre of 1:512. His parents were also seropositive (1:128 and 1:64). Despite anti-Toxoplasma treatment (not specified), the child died 3 weeks later; post-mortem examination was not performed. In another report, Rifaat et al. (Reference Rifaat, Sadek and Elazghal1973a) first isolated viable T. gondii from human placenta. A 30-year-old woman aborted an edematous macerated 22 weeks gestational age fetus. The fetus also had hydrocephaly. Viable T. gondii was isolated from the placenta (by mouse inoculation) but not from the fetal brain. Thus, there is no definitive evidence of congenital toxoplasmosis in either of these reports.

Other reports on congenital toxoplasmosis in Egypt are very conflicting and mainly published in local journals which are not widely accessible (Table 4). Most of these reports are based on serological results on single samples from pregnant women. The serologic diagnosis of acute maternal infection based on single serum sample is difficult because IgM antibodies can persist for months and the avidity index might remain low for several months (Peyron et al., Reference Peyron, Wallon, Kieffer, Graweg, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2016), thus definitive diagnosis requires the sequential appearance of specific IgM and IgG antibodies in the same sample. Detection of T. gondii in amniotic fluid can confirm the diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis and has been reported by Eida et al. (Reference Eida, Eida and Ahmed2009) and El Deeb et al. (Reference El Deeb, Salah-Eldin, Khodeer and Allah2012). However, no clinical follow-up was reported.

Although T. gondii-infected women can abort, toxoplasmosis is not a common cause of habitual abortion in women (reviewed in Dubey and Beattie, Reference Dubey and Beattie1988). Numerous women in Egypt who aborted fetuses have been tested for toxoplasmosis (Table 4). In some of the reports, T. gondii DNA was detected in placentas or unspecified products of conception. Once again, the accuracy of PCR requires stringent controls to minimize contamination. Caution is needed that the presence of T. gondii DNA in placenta does not equate with congenital infection.

An estimate of the rate of congenital toxoplasmosis can be obtained by data on seroconversion of mothers during pregnancy, serological testing of fetus during pregnancy and after parturition, and clinical follow-up of newborn children. There are no concrete data concerning prevalence of congenital toxoplasmosis in Egypt. To confirm congenital infection, sera would be tested at 12 months showing IgG presence or evidence of neo-synthetized antibodies by Western-blot in children blood from birthday or 3 months of age (Robert-Gangneux and Dardé, Reference Robert-Gangneux and Dardé2012).

In summary, there is no definitive evidence of toxoplasmosis abortion or definitive diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis in any of these cases.

Post-natal clinical toxoplasmosis

Lymphadenopathy, fever and ocular involvement are some of the common symptoms of acquired toxoplasmosis (Peyron et al., Reference Peyron, Wallon, Kieffer, Graweg, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2016). In addition to the report of these symptoms in pregnant women in Egypt discussed by Eida et al. (Reference Eida, Eida and Ahmed2009), there are few other reports of toxoplasmosis-associated lymphadenopathy from Egypt (Azab et al., Reference Azab, Rifaat, Khalil, Safer and Nabaweya1983; Tolba et al., Reference Tolba, El-Taweel, Khalil, Hazzah and Heshmat2014) based on mainly serologic examination. There are also a few reports of ocular toxoplasmosis in Egypt (Table 7). Rifaat et al. (Reference Rifaat, Sadek, Elnaggar and Munir1973b) studied the case of an 18-year-old female student who complained of headache and impaired vision in the right eye. Based on the revealed lesions of uveitis altogether with the positive DT titre (1:128), authors diagnosed the case as toxoplasmic uveitis. This case was treated with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine for 2 weeks. A month after treatment, lesions regressed, the vision acuity was enhanced. Based on positive serology and the lesion, ocular toxoplasmosis has been reported by others (Azab et al., Reference Azab, Rifaat, Khalil, Safer and Nabaweya1983; El-Ridi et al., Reference El-Ridi, Nada, Abdul-Fattah, Habeeb and Awad1991a; Safar et al., Reference Safar, Abd-el Ghaffar, Saffar, Makled, Habib, El Abiad and El Shabrawy1995). Recently, Tolba et al. (Reference Tolba, El-Taweel, Khalil, Hazzah and Heshmat2014) reported three chorioretinitis cases from Alexandria; the three cases were IgG-positive, while a single case had IgM antibodies. No test was performed in aqueous or vitrous humour.

Table 7. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in suspected ocular patients from Egypt

NS, not stated; ND, not done; +ve, positive.

a Antibody titres are given in means.

Toxoplasmosis in animals

Toxoplasmosis can cause severe illness in many domestic and wild animal species. It is a common cause of abortion in sheep and goats worldwide (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). Many species of animals, such as New World primates, Australasian marsupials, Pallas and Sand cats, are highly susceptible to acute toxoplasmosis, whereas cattle, buffaloes and horses are resistant to toxoplasmosis (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). Additionally, animals appear reservoirs of T. gondii infection. Humans become infected postnatally by ingesting food and water contaminated with oocysts shed by felids and by eating undercooked meat. Available information on T. gondii infection in domestic animals from Egypt is summarized here.

Cats

The published seroprevalence estimates in cats are highly variable (12.5–97.4%) (Table 8), depending on the life style and age of cats and the serological test. It is noteworthy that five of the six surveys are from Cairo and Giza governorates.

Table 8. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in cats from Egypt

A very high seroprevalence (>95%) of T. gondii was reported in stray cats. The specificity of the MAT for cats was confirmed by isolation of viable T. gondii (Al-Kappany et al., Reference Al-Kappany, Rajendran, Ferreira, Kwok, Abu-Elwafa, Hilali and Dubey2010). Brains, hearts and tongues from 112 seropositive cats were bioassayed individually in mice. Toxoplasma gondii was isolated from 83 hearts, 53 tongues and 36 brains. We are not aware of any report of clinical toxoplasmosis in cats from Egypt.

Cats are the key hosts in the epidemiology of T. gondii because they are the only hosts that can excrete environmentally resistant oocysts in feces. There is limited information on T. gondii oocyst excretion by cats in Egypt (Table 9). Of these, two reports by Rifaat et al. (Reference Rifaat, Arafa, Sadek, Nasr, Azab, Mahmoud and Khalil1976c) and Al-Kappany et al. (Reference Al-Kappany, Rajendran, Ferreira, Kwok, Abu-Elwafa, Hilali and Dubey2010) need comment. Rifaat et al. (Reference Rifaat, Arafa, Sadek, Nasr, Azab, Mahmoud and Khalil1976c) found T. gondii-like oocysts in feces of 88 (41.3%) of 213 stray cats trapped from Cairo and Giza. A total of 318 cats were trapped, euthanized and blood and feces were collected for T. gondii testing. Antibodies to T. gondii were found in 126 (39.6%) by the DT. Nearly half of the cats were considered adults based on weights of cats. Out of these 318 cats, feces of 213 cats were tested for coccidian oocysts. Feces with T. gondii-like oocysts were bioassayed in mice, and the identity of Toxoplasma oocysts was proven by sub-inoculation of infected mouse tissues to clean mice. Toxoplasma gondii-like oocysts were found in 88 cats (20 in 6–8 weeks old, six in 9–12 weeks old, seven in 4–5 months old and 55 in cats older than 6 months). Serological results and oocyst excretion were compared in 33 cats; 14 (35.7%) of 33 cats excreting oocysts were seropositive, and 19 (15.8%) were seronegative. Thus, both seropositive and seronegative cats were excreting oocysts. From the results presented, it is uncertain whether the results were based solely on the presence of antibodies in mice fed oocysts or demonstration of T. gondii in mouse tissues. If the results were based on serology alone, then data will not exclude the related parasite, Hammondia hammondi infection (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). There are no archived data or specimens for validation. At any rate, this report from Egypt is the highest prevalence of excretion of T. gondii-like oocysts compared with reports from other countries (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010).

Table 9. Prevalence of T. gondii-like oocysts in fecal samples from cats in Egypt

a See comments in the text.

b T. gondii DNA was isolated from both cases.

Al-Kappany et al. (Reference Al-Kappany, Rajendran, Ferreira, Kwok, Abu-Elwafa, Hilali and Dubey2010) did not find T. gondii oocysts in feces of 158 stray cats from Giza, probably because most (97.4%) were seropositive to T. gondii and had already excreted oocysts. Awadallah (Reference Awadallah2010) found T. gondii-like oocysts in 25 (50%) of 50 cat feces from Sharkia; however, oocysts identity was not confirmed by bioassay or PCR.

Toxoplasma gondii oocysts are excreted only for a short period (<2 weeks) in the life of the cat and by the time cats become seropositive, oocysts have already been excreted. However, cats can re-excrete oocysts more than once in life (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010).

Isolation of T. gondii oocysts from the environment

It is technically difficult to isolate T. gondii oocysts from running water (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). However, Elfadaly et al. (Reference Elfadaly, Hassanain, Hassanain, Barakat and Shaapan2018) observed T. gondii-like oocysts in seven (2.9%) of 245 water samples collected from ground pumps (water supplies) in rural areas of Giza governorate. The identity of the recovered oocysts was not confirmed. El-Tras and Tayel (Reference El-Tras and Tayel2009) tested 30 water samples from irrigation canals by bioassay in mice. It is not clear whether all samples were infected, and if samples were inoculated separately or in pools. After 6 weeks, sera of inoculated mice were tested using direct agglutination test for T. gondii; five were reported to be positives; however, the antibody titres were not stated and mice were not tested for viable T. gondii. They also bioassayed in kittens’ 30 vegetable samples irrigated by the sampled water. Four cats excreted T. gondii-like oocysts; however, oocysts infectivity was not reported, and it is not clear if the kittens were tested for T. gondii antibodies before use in the experiment. Recently, methods for detection and viability measure of T. gondii oocysts were described and they could be employed in Egypt in order to determine the contamination of the environment (Rousseau et al., Reference Rousseau, Villena, Dumètre, Escotte-Binet, Favennec, Dubey, Aubert and La Carbona2019).

Dogs

Dogs are considered a source of infection for humans because they roll over and eat cat feces among other foods ingested (Frenkel et al., Reference Frenkel, Lindsay, Parker and Dobesh2003). Antibodies to T. gondii have been demonstrated in the sera of dogs and viable T. gondii has been isolated from naturally infected dog tissues (Table 10). Nothing is known of clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs from Egypt.

Table 10. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in stray dogs from Egypt

ND, not done.

a Viable T. gondii was isolated from the brains of two dogs.

b Viable T. gondii was isolated from 22 out of 43 hearts of seropositive dogs.

Food animals

Sheep

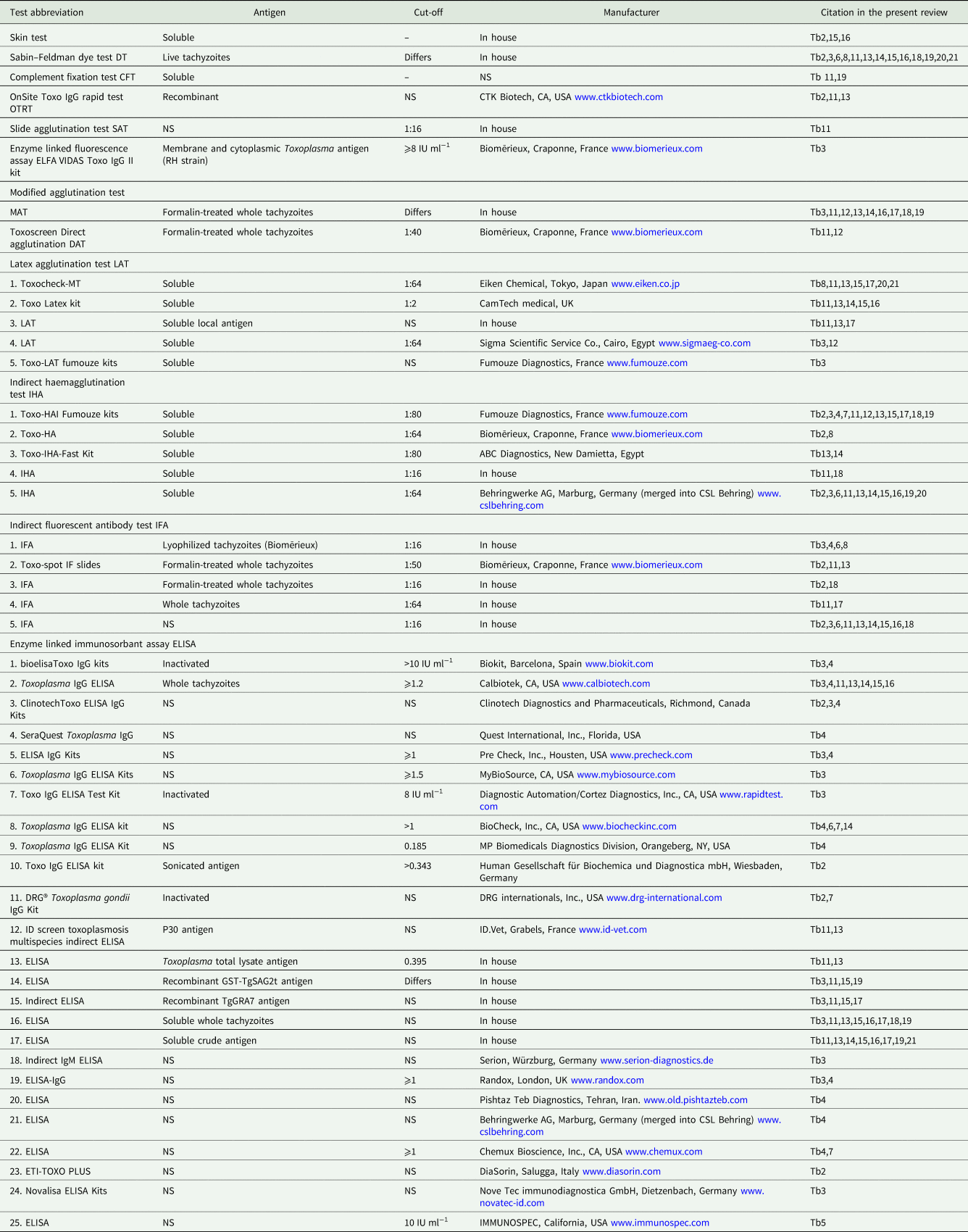

The estimated sheep population in Egypt is 5.5 million (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015). Sheep meat is widely consumed in Egypt, especially during religious holidays. The consumption of undercooked dish ‘Kabob and kofta’ is popular (Hassan-Wassef, Reference Hassan-Wassef2004), which favours T. gondii transmission to humans. Most reports used sera from sheep at abattoirs, while few studies were conducted on sheep in farms (Table 11). In a histological study, T. gondii tissue cysts were noted in brain sections of two out of 60 sheep from a herd in Suez governorate (Anwar et al., Reference Anwar, Mahdy, El-Nesr, El-Dakhly, Shalaby and Yanai2013); we consider the two tissue cysts illustrated in Figure 4 of their paper as Sarcocystis cysts (J.P. Dubey, own opinion).

Table 11. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in sheep from Egypt

a Fifty-four were examined: 27 from Menoufiya governorate and 37 from Tahrir province (currently known as Beheira governorate).

Toxoplasma gondii is an important cause of abortion in sheep worldwide but little is known of its occurrence in sheep from Egypt (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). Direct evidence of ovine congenital toxoplasmosis was provided by Rifaat et al. (Reference Rifaat, Morsy, Sadek, Arafa, Azab and Abdel Ghaffar1977a) who isolated viable T. gondii by mouse bioassay from tissues of an aborted lamb. Toxoplasma gondii DNA has been demonstrated in aborted fetal tissues (Table 12). Finding T. gondii parasites or T. gondii DNA only indicates congenital transmission. Histopathological evaluation and exclusion of other causes of abortion are necessary to establish cause–effect relationship. Serological testing of ewes is of little help because high levels of T. gondii IgG can persist for months and IgM antibodies have already peaked in aborted ewes (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010).

Table 12. Diagnosis of T. gondii in pregnant or aborted sheep and goats from Egypt

ND, not done; NS, not stated; +ve, positive; −ve, negative.

Numbers in parenthesis are percentages.

a Viable T. gondii was isolated from tissues of two stillborns, see comment in the text.

b Brucella, Salmonella, Chlamydia and Neospora caninum

c Details were not given.

d Data are not separated between T. gondii and Brucella melitensis.

e Tachyzoites were found in placental sections, however neither details nor illustrations were given.

Goats

Goat population in Egypt is ~4 million. Goats are usually reared within sheep herds. In a popular system in Egypt, particularly in suburban areas, small numbers of goats are kept in houses, and can roam to feed on the garbage along with cats and dogs. Using different serological tests, high T. gondii seroprevalence was reported from goats in Egypt (Table 13).

Table 13. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in goats from Egypt

Like sheep, little is known of toxoplasmal abortion in goats from Egypt; available information is summarized in Table 12. Ramadan et al. (Reference Ramadan, Abdel-Mageed and Khater2007) found IgG antibodies in 17 (35.4%) of 48 pregnant Balady goats from Kalubiya governorate; 11 (22.9%) of them had IgM. Three goats in the mid pregnancy stage were sulfadimidine-treated for 5 successive days, while another three kept untreated as controls. No abortions had occurred in the treated group and the delivered kids were seronegative, while one of the untreated goats delivered two seropositive-stillborns (IgG and IgM). Viable T. gondii was isolated from tissues of the stillborns.

Transmission of T. gondii to humans by consumption of raw goat milk is of public health significance (Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Verma, Ferreira, Oliveira, Cassinelli, Ying, Kwok, Tuo, Chiesa and Jones2014). Consumption of goat milk is popular in Egyptian rural areas. Abdel-Rahman et al. (Reference Abdel-Rahman, El-Manyawe, Khateib and Saba2012) fed eight cats raw milk from eight seropositive goats (four IgG and four IgM positive goats); we are not aware of the validity of the used commercial kits. Toxoplasma gondii-like oocysts were found in feces from all cats of the IgM group and one cat from the IgG group; however, oocysts infectivity was not proven. Sadek et al. (Reference Sadek, Abdel-Hameed and Kuraa2015) found T. gondii tachyzoites, respectively, in five of 58 and six of 47 milk samples from sheep and goats; this is a very high proportion and the illustrations are not clear. In addition, Ahmed et al. (Reference Ahmed, Shafik, Ali, Elghamry and Ahmed2014) found T. gondii DNA in four (8%) of 50 milk samples from goats. The presence of T. gondii DNA in milk does not mean the viability of the parasite.

Camels

In Egypt, camel meat is inexpensive and consumed mainly in some governorates such as Cairo, Kalubiya, Sharkia and Assiut. It seems that the published reports of toxoplasmosis in camels from Egypt do not reflect the true prevalence in Egyptian camels because most of the sampled camels were imported, particularly those slaughtered at the official abattoir in Cairo (El Basateen). Seroprevalence data are summarized in Table 14. Moreover, T. gondii oocysts were revealed from cats fed pooled meat samples from camels (Abdel-Gawad et al., Reference Abdel-Gawad, Nassar and Hilali1984). Toxoplasma gondii DNA was not found in 50 raw camel milk samples (Saad et al., Reference Saad, Hussein and Ewida2018).

Table 14. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in camels from Egypt

a MAT was conducted using formalin-treated whole tachyzoites from different antigen; 1RH strain, 2local equine strain, 3local camel strain and 4local sheep strain.

Cattle and water buffaloes

Both cattle and buffaloes are considered resistant to T. gondii infection (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). Apparently, they can clear the infection in their tissues and their role in transmission to humans is uncertain; however, some reports indicated the substantial role of beef in T. gondii transmission (Opsteegh et al., Reference Opsteegh, Prickaerts, Frankena and Evers2011; Belluco et al., Reference Belluco, Patuzzi and Ricci2018). Although antibodies to T. gondii have been reported in both species in Egypt (Tables 15 and 16), viable parasite has not been isolated from beef.

Table 15. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in cattle from Egypt

Table 16. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in water buffaloes from Egypt

El-Tras and Tayel (Reference El-Tras and Tayel2009) isolated viable T. gondii from tissues of two out of 30 buffaloes; however, it needs confirmation because there are no valid reports on the isolation of T. gondii from buffalo meat (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010), and the parasite was not found in tissues of three calves experimentally infected with 200 000 T. gondii oocysts (de Oliviera et al., Reference de Oliviera, da Costa, Bechara and Sabatini2001). Moreover, T. gondii DNA was not found in 50 milk samples from cows (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Shafik, Ali, Elghamry and Ahmed2014). The report of the presence of T. gondii DNA in 6% (3/50) of buffalo bull semen samples from Egypt needs confirmation (Abd El-Razik et al., Reference Abd El-Razik, Mahmoud, Sakr, Sosa, Hasanain, Ahmed and Nawito2017).

Pigs

Due to religious concerns, pork is not popular in Egypt. Pigs are reared in small holdings mainly in Cairo and Kalubiya within a complete garbage feeding system including food remnants, rodents, and dead animals and birds. Thus, they are excellent indicators for the spread of T. gondii infection. Reports on the seroprevalence of T. gondii in pigs from Egypt are given in Table 17.

Table 17. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in pigs from Egypt

a Viable T. gondii was isolated by both mice and cat bioassay.

b Forty (40.0%) had IgM antibodies.

Viable T. gondii was isolated from two seropositive pigs (Botros et al., Reference Botros, Moch and Barsoum1973) and seven (23.3%) of 30 pigs by mouse bioassay (Ghattas, Reference Ghattas1999). Ghattas (Reference Ghattas1999) fed cats (T. gondii-seronegative) meats from seropositive pigs. Cats excreted T. gondii-like oocysts. The identity of the recovered oocysts was confirmed by oral inoculation in mice.

Equines

Generally, high T. gondii seroprevalences were reported in horses and donkeys from Egypt (Table 18). However, equine meat is not consumed by humans in Egypt. Anti-T. gondii antibodies were noted in seven out of 15 donkey milk samples (Haridy et al., Reference Haridy, Saleh, Khalil and Morsy2010).

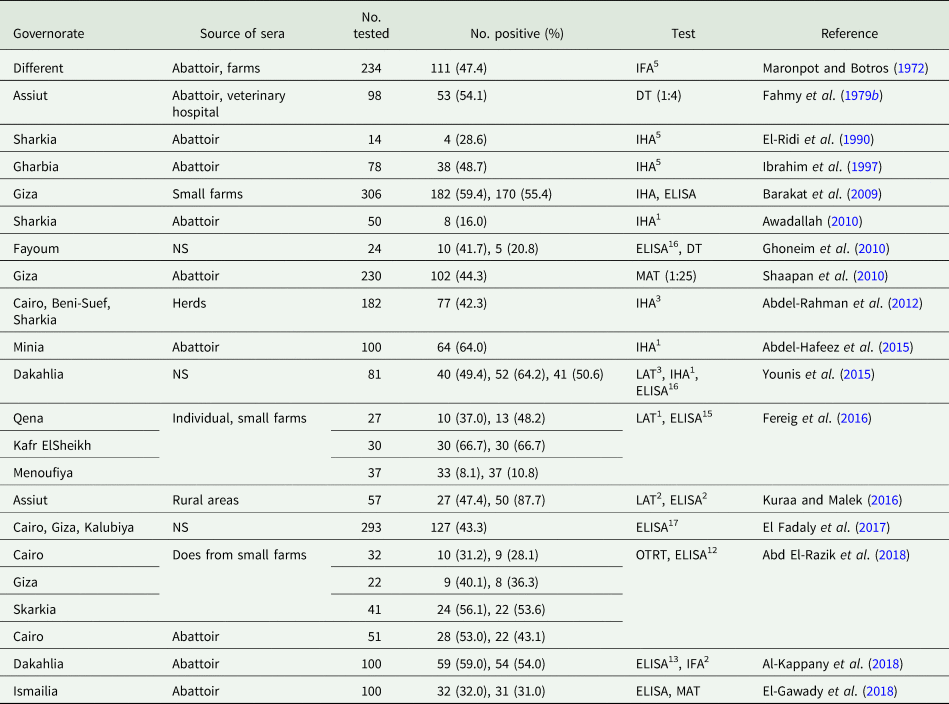

Table 18. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in equines from Egypt

a ELISA were carried out using 1crude antigen (LA) prepared from local horse strain, and its purified immunogenetic fractions; 2bound (LAb) and 3unbound (LAunb) fractions.

b MAT was carried out using formalin-treated whole tachyzoites from different antigen; 1RH strain, 2local equine strain, 3local camel strain and 4local sheep strain.

Viable T. gondii has been isolated from tissues of 25 slaughtered donkeys at Giza zoo abattoir. Toxoplasma gondii-like oocysts were found in nine of 25 cats fed donkey tissues (Younis et al., Reference Younis, Abou-Zeid, Zakaria and Mahmoud2015); however, the identity of these oocysts was not confirmed. Moreover, viable T. gondii were isolated from horses slaughtered at the same zoo (Shaapan and Ghazy, Reference Shaapan and Ghazy2007). Donkeys and horses are slaughtered in the zoo for feeding of wild felids which can excrete T. gondii oocysts.

Chickens and other avian species

Chickens and ducks are widely consumed in Egypt due to their relatively cheap prices in comparison to red meats. Free range (FR) system of rearing birds is common in rural areas particularly in villages of Upper Egypt. FR birds are considered as a common source of human infection (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). High seroprevalence was reported from FR chicken in Egypt, indicating high oocyst-environmental contamination (Table 19). Hassanain et al. (Reference Hassanain, Zayed, Derbala and Kutkat1997) stated a direct correlation between T. gondii seroprevalence and the decrease in egg production, although the seropositives were at low titres (⩽1:64) and the parasite isolation was not done. Viable T. gondii was isolated from both FR and commercially farmed chicken in Egypt (Table 21).

Table 19. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in chickens from Egypt

FR, free range chickens; H, house-bred chickens; M, market chickens; C, commercially farmed chickens; SH, slaughterhouse.

a Six hundred laying hens from three flocks (each of 12000 birds) suffered from drop in eggs production and high percent of embryonic mortalities.

b This test is wrongly identified in the report as MAT.

Table 20. Seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies in rodents from Egypt

a Viable T. gondii was isolated from brain pools by mice bioassay.

b Viable T. gondii was isolated by both mice and cat bioassay.

Table 21. Trials to isolate viable T. gondii from tissues of food animals and birds in Egypt by mice bioassay

ND, not done; NC, not clear; FR, free range; C, commercially farmed.

a The studied samples were from seropositive animals.

Little is known of toxoplasmosis in ducks. In Egypt, T. gondii seroprevalence ranges from 10.5 to 55% using different serological tests in different duck breeds (El-Massry et al., Reference El-Massry, Mahdy, El-Ghaysh and Dubey2000; Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Graham, Dahl, Hilali, El-Ghaysh, Sreekumar, Kwok, Shen and Lehmann2003; Harfoush and Tahoon, Reference Harfoush and Tahoon2010; AbouLaila et al., Reference AbouLaila, El-Bahy, Hilali, Yokoyama and Igarashi2011; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Osman, Mohamed, Al-Selwi, Nishikawa and Abdel-Ghaffar2018). Viable T. gondii was isolated from one of three seropositive FR ducks from Beheira governorate (Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Graham, Dahl, Hilali, El-Ghaysh, Sreekumar, Kwok, Shen and Lehmann2003).

In other avian species, T. gondii seroprevalence was reported from 29.8% of 188 quails (Shaapan et al., Reference Shaapan, Khalil and Abu El Ezz2011), and 59.5% of 173 turkeys (El-Massry et al., Reference El-Massry, Mahdy, El-Ghaysh and Dubey2000) and 12.5% of 120 Ostriches (El-Madawy and Metawea, Reference El-Madawy and Metawea2013). The latter found T. gondii DNA in the blood of nine ostriches. Additionally, T. gondii antibodies were reported from pigeons (Rifaat et al., Reference Rifaat, Morsy and Sadek1969; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Osman, Mohamed, Al-Selwi, Nishikawa and Abdel-Ghaffar2018).

Rabbits

Prevalence of T. gondii in rabbits from different Egyptian governorates is variable and ranges from 0 to 37.5% (Hilali et al., Reference Hilali, Nassar and Ramadan1991; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Huang, Salem, Talaat, Nasr, Xuan and Nishikawa2009; Harfoush and Tahoon, Reference Harfoush and Tahoon2010; Ashmawy et al., Reference Ashmawy, Abuakkada and Awad2011; Abou Elez et al., Reference Abou Elez, Hssanen, Tolba and Elsohaby2017). Despite some reports placing the rabbit as a major source for human infection (Almeria et al., Reference Almería, Calvete, Pagés, Gauss and Dubey2004), we think that the role of rabbits is not of such importance because 90% of rabbits in Egypt are fed commercial pellets in small farms and kept in hutches or cages, which limit the chances of oocyst ingestion.

Rodents

Rodents are important for T. gondii epidemiology because they serve as a source of infection for cats (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010). Reports on the seroprevalence of T. gondii in different species of rodents from Egypt are given in Table 20. Viable T. gondii was isolated by mouse bioassay (Rifaat et al., Reference Rifaat, Mahdi, Arafa, Nasr and Sadek1971, Reference Rifaat, Nasr, Sadek, Arafa and Mahdi1973d, Reference Rifaat, Arafa, Sadek and Nasr1976a) and/or cat bioassay (El Fadaly et al., Reference El Fadaly, Ahmad, Barakat, Soror and Zaki2016).

Isolation of viable T. gondii from food animals

Viable T. gondii was isolated from tissues of different food animals and birds in Egypt by mouse bioassay (Table 21). Cat bioassay was also used in some studies, and T. gondii-like oocysts were excreted from cats fed pooled meat samples. However, no further definitive procedures for theses oocysts were done in many studies (Abdel-Gawad et al., Reference Abdel-Gawad, Nassar and Hilali1984; El-Massry et al., Reference El-Massry, Abdel-Gawad and Nassar1990; Hassanain et al., Reference Hassanain, Elfadaly, Shaapan, Hassanain and Barakat2011).

Perspective

There are many reports on toxoplasmosis in animals and humans from Egypt, but there is no statistically-valid prevalence study on the national level. Little is known concerning clinical toxoplasmosis in humans or livestock in Egypt. Toxoplasmosis is usually considered by the physicians in Egypt as a cause of abortions and complications in pregnant women; however, the published studies are not well-structured and lack definitive diagnosis. There is a great need to establish a well-planned study concerning congenital toxoplasmosis in Egypt. Reports on toxoplasmosis in animals were based on commercial kits with unconfirmed validity. A large-scale study is needed employing validated serological methods and includes procedures for isolation of the parasite to critically evaluate the role of different food animals from Egypt in the transmission of T. gondii to humans.

Acknowledgements

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This work is dedicated to late Professor Mosaad Hilali, Parasitology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt.

Financial support

Ibrahim Abbas is the recipient of a junior visit grant (USC17: 141) supported by the US-Egypt Science and Technology (STDF) Joint Fund.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.