Introduction

Clonorchis sinensis (C. sinensis) infection remains a major medical burden, especially in Asia and Eastern Europe, with an estimated 15 million infected people (Qian et al. Reference Qian, Chen, Liang, Yang and Zhou2012). With a relatively long life cycle of C. sinensis at 10–20 years (Attwood and Chou, Reference Attwood and Chou1978), the chronic infection with C. sinensis is associated with cholangiocarcinoma (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Rim and Bak1993; Watanapa and Watanapa, Reference Watanapa and Watanapa2002; Papachristou et al. Reference Papachristou, Schoedel, Ramanathan and Rabinovitz2005; Choi et al. Reference Choi, Lim, Lee, Lee, Choi, Heo, Jang, Lee, Kim and Hong2006), posing a serious health risk to humans. The rate of intestinal parasitic infection in Korea, mostly caused by soil-transmitted helminths such as Trichocephalus trichiurus, Ascaris lumbricoides and Ancylostoma duodenale, used to be high, but decreased dramatically, to under 3%, according to a national survey in 2013 (Cho et al. Reference Cho, Chung and Lee2013). Despite the reduction in the incidence of infections with the soil-transmitted helminth, the infection with snail-transmitted helminth C. sinensis persists, currently being the major intestinal parasite in Korea, with ~70% of all infection cases (Cho et al. Reference Cho, Chung and Lee2013). Clonorchis sinensis infection is usually caused by eating raw fish, and evidently, people living near one of the five major rivers in Korea with a raw-fish eating habit show a high infection prevalence (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Cheun, Cheun, Lee, Kim, Lee, Lee and Cho2010a). Despite continued use of the drug praziquantel (Loscher et al. Reference Loscher, Nothdurft, Prufer, von Sonnenburg and Lang1981), infection with C. sinensis persists in the Korean population owing to the absence of reliable diagnostics. Even though a crude lysate or excretory–secretory proteins of C. sinensis (CsESPs) have been reported to be good sensitive serodiagnosis antigens (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Park, Li and Hong2003), it is difficult to obtain them in a sufficient amount, and they show cross-reactivity with similar parasites (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Park, Li and Hong2003). Thus, we need recombinant antigens for sensitive assays. Although much effort has been devoted to finding antigens for specific and highly sensitive assays, there remains an unmet need for accurate and sensitive serodiagnostics for early management of C. sinensis infection (Ju et al. Reference Ju, Joo, Lee, Cho, Cheun, Kim, Lee, Lee, Sohn, Kim, Kim, Park and Kim2009; Li et al. Reference Li, Shin, Cho, Kim, Hong and Hong2011, Reference Li, Hu, Liu, Huang, Xu, Zhao, Wu and Yu2012; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Zheng, Li, Yang, Li, Zeng, Yu, Huang and Hu2013; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Chen, Tian, Mao, Lv, Shang, Li, Yu and Huang2014). Previously, adenylate kinase 1 of C. sinensis (CsAK1) has been identified as a potential serodiagnosis target antigen (Liang et al. Reference Liang, Zhang, Chen, Hu, Huang, Li, Ren, He, Li, Li, Xu, Wu, Lu and Yu2013b), and was verified as a component of CsESPs and was confirmed to be immunoreactive towards serum samples from C. sinensis-infected rats.

With the aim to identify new candidate antigens for serodiagnosis of C. sinensis infection, here we performed in silico screening using the transcriptome database CsUniDB v3.0 (Yoo et al. Reference Yoo, Kim, Ju, Cho, Kim, Cho, Choi, Park, Kim and Hong2011), and identified adenylate kinase 3 of C. sinensis (CsAK3) as a potential relevant secretory protein (Fig. 1A). Previously, CsAK3, as an isotype of CsAK1, was evaluated for its biochemical activities (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Yu, Wu, Xu, Song, Zhang, Hu, Zheng, Guo, Xu, Dai, Ji, Gu and Ying2005), but its histochemical properties and potential use as a serodiagnosis target have not yet been reported. The efficacy of an immune-reaction-based diagnosis largely depends on the quality of recombinant antigens, where the purity and conformation determine the specificity of antigen–antibody reactions. Thus, a robust expression system ensuring solubility and biologically relevant conformation is desirable. Here, CsAK3 was expressed in soluble form in Escherichia coli (E. coli) using the N-terminal RNA-interacting domain of human LysRS (hRID) (Francin et al. Reference Francin, Kaminska, Kerjan and Mirande2002) as a novel soluble carrier and immunologically tailored folding vehicle. Then, the immunostaining profiles of C. sinensis were investigated. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using recombinant CsAK3 and the serum samples from C. sinensis-infected patients suggest that CsAK3 could serve as a candidate antigen for improving the clinical serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis.

Fig. 1. Prediction of a signal peptide and transmembrane domain and a phylogenetic tree of AK3. (A) Phobius software was used to predict the presence of a transmembrane domain (T.M.) and signal peptide (S.P.) in the AK3 of Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma mansoni, Homo sapiens, Oryctolagus cuniculus, Rattus norvegicus, Mus musculus and Drosophila melanogaster. (B) The phylogenetic tree was constructed using Phylogeny.fr. Sequence similarity (%) to AK3 of C. sinensis (CsAK3) is shown on the right.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The animal experiments were approved and reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Yonsei University Health System, Seoul, Korea (IACUC No. 2013-0300 and 2016-0343). They were also conducted in accordance with the internationally accepted principles for laboratory animal use and care as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines (NIH publication No. 85-23, 1985, revised 1996). Animal experiments were conducted at animal biosafety level-3 facilities, and the animal facility was certified by the Ministry of Food and Drug Administration and by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (LNL08-402).

Human serum

Serum samples of C. sinensis-infected patients and negative serum samples were obtained from the Department of Environmental Medical Biology, Yonsei University College of Medicine in Seoul, Korea, with consent of the patients. Parasitic infections were confirmed by ELISA, using crude lysate of the worms, based on a proven high sensitivity (88.2%) and specificity (100%) for infection against healthy people (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Park, Li and Hong2003; Hong and Fang, Reference Hong and Fang2012). The crude lysate of other parasites, such as Paragonimus westermani, Spirometra spp or Cysticercus cellulosae, was used for comparison.

Prediction of secretion and the construction of a phylogenetic tree

The Phobius website was used to predict the signal peptide and transmembrane domain (Kall et al. Reference Kall, Krogh and Sonnhammer2004, Reference Kall, Krogh and Sonnhammer2005, Reference Kall, Krogh and Sonnhammer2007). The proteins with a signal peptide but without a transmembrane domain were initially classified as proteins with a good secretory potential (Young et al. Reference Young, Nagarajan, Lin, Korhonen, Jex, Hall, Safavi-Hemami, Kaewkong, Bertrand, Gao, Seet, Wongkham, Teh, Wongkham, Intapan, Maleewong, Yang, Hu, Wang, Hofmann, Sternberg, Tan, Wang and Gasser2014). As a means of evaluating the genetic relatedness, a phylogenetic tree was constructed by Phylogeny.fr and edited in Jalview, with calculation of the ‘average distance’ based on the percentage of identity (Dereeper et al. Reference Dereeper, Guignon, Blanc, Audic, Buffet, Chevenet, Dufayard, Guindon, Lefort, Lescot, Claverie and Gascuel2008, Reference Dereeper, Audic, Claverie and Blanc2010). Sequences of the protein were collected from NCBI: CsAK3 (AAV40857.1), Opisthorchis viverrini (XP_009162289.1), Schistosoma japonicum (AAW25461.1), Schistosoma mansoni (XP_018646897.1), Drosophila melanogaster (NP_001287280.1), Mus musculus (AAH19174.1), Rattus norvegicus (BAA02379.1), Oryctolagus cuniculus (AAL07503.1) and Homo sapiens (AAH1377.1) were selected for further analysis.

Clonorchis sinensis culture and preparation of a cell lysate and excretory–secretory proteins

The protocol was modified from the previous report (Sim et al. Reference Sim, Park and Yong2003). Metacercariae of C. sinensis were obtained from freshwater fish caught in a reservoir in Jin-ju Province, Gyeongsangnam-do, Korea. Sprague–Dawley rats were infected orally with 200 C. sinensis metacercariae. Six weeks after infection, adult C. sinensis worms were collected from the bile ducts of the rats. They were used immediately for the preparation of a crude lysate, and immunohistochemical analysis, or stored at −70 °C until use. For the preparation of a crude lysate, we placed adult C. sinensis worms in a mortar and cooled them with liquid nitrogen. The worms were finely ground and powdered, and then the powder was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). We removed debris by centrifugation (15 000 × g/1 h), and the supernatant served as a crude lysate of C. sinensis. For the preparation of excretory–secretory proteins (ESPs), adult C. sinensis worms in the DMEM medium were cultivated in a CO2 incubator for a week. The culture medium was collected and centrifuged to remove the debris and C. sinensis sperms, and the supernatant was used as a solution of ESPs from C. sinensis.

Expression vector construction

The pGE-hRID3 vector was constructed from the previously constructed pGE-LysRS vector (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Han, Kim, Ryu, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kang, Shin, Lim, Kim, Hyun and Seong2008) by replacing LysRS with hRID–tev site–6 × His tag. cDNA of CsAK3 was synthesized from total RNA of adult C. sinensis by RT-PCR using Maxime RT-PCR PreMix Kit (iNtRON BIOTECHNOLOGY, Korea, 25131) with oligo-dT and specific primers [5′-gtcacg catatg(Nde I site) aggtcaacgcggccaatg, 5′-gtcacg ggatcc(BamH I site) aggtcaacgcggccaatg and 5′-gtcacg aagctt(Hind III site) tcacttgtattccgtgtattg], following manufacturer's instruction. The cDNA was inserted into the pGE-hRID3 vector via Nde I /Hind III or BamH I /Hind III cleavage for the expression of CsAK3 as a wild-type or fusion form, respectively.

Protein expression

Each plasmid was transfected into E. coli BL21*(pLysS) competent cells (Novagen), and the cells were screened for resistance to ampicillin (50 µg mL−1) and chloramphenicol (34 µg mL−1). Next, 0.75 mL of overnight-cultured cells was added to 15 mL of the Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C. After growth to optical density at 600 nm (OD600) >0.5, 1 mm isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 3.5 h. The cells were harvested and stored at −80 °C. The stored cells were lysed in PBS by sonication. The total cell lysates (T) were centrifuged at 12 000 × g for 12 min to separate the soluble (S) from the pellet fractions (P). Each fraction was analysed by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Elpis, Korea, EBP-1011). Solubility of a target protein was calculated by dividing the amount in the soluble fraction by the amount in the total fraction. This procedure was repeated three times.

Purification and quantification

The transformed BL21*(pLysS) cells were incubated in 400 mL of the LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics. After OD600 reached >0.7, 1 mm IPTG was added and incubated at 30 °C for 4 h, and then the cells were harvested and stored in a −80 °C freezer. The stored cells were lysed in 10 mL of buffer A (50 mm Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 300 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Tween 20 and 10 mm imidazole, filtered and degassed) by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 12 000 × g for 12 min, and the soluble fraction was filtered by means of a 0.45 µm syringe filter (HYUNDAI Micro, Korea, SP25P045S) and loaded onto a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare LifeSciences, England, 17-5248-02). Using buffer A and buffer B (50 mm Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 300 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Tween 20 and 300 mm imidazole, filtered and degassed), the proteins were eluted with an increasing imidazole concentration. Purified proteins were dialysed against storage buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT) and concentrated by means of Centriprep (Millipore, Germany, Centriprep 30 K device, cat. # 4306). After sequential dilution, the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. The amount of each protein was estimated by densitometry scanning of the protein bands using Bio1D software, in comparison with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

Immunization of mice

Eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 50 µg of the purified recombinant CsAK3 mixed with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant (Sigma, MO, USA). Two weeks later, the mice were boosted with the same amount of the antigen, followed by second boosting with 20 µg of the antigen without adjuvant via the tail vein. Three days later, the mice were euthanized, bled and the immune sera were harvested by centrifugation.

Western blotting

Expressed and purified proteins were analysed by SDS-PAGE. The hRID-CsAK3 fusion protein was cleaved at the linker site by Actev protease (Invitrogen, CA, USA, 12575-015) at room temperature for 1 h. The total lysate (40 µg) and ESPs (10 µg) of adult C. sinensis were also analysed. After electrophoresis, resolved protein bands were transferred and immobilized onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, ISEQ00010). After that, 5% (w/v) skim milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% of Tween 20 (TBST) was used to block the membrane for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes with TBST, the membrane was treated with Penta•His Antibody (QIAGEN, Germany, 34660) or serum samples from immunized mice, clonorchiasis patients as well as from healthy people, and incubated at 4 °C overnight. After three washes with TBST, an anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma, A4416) or anti-human IgG antibody (Abfrontier, Korea, LF-SA5006) was used as a secondary antibody and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Each serum was diluted in TBST to various concentrations for optimization.

Immunohistochemical analysis of adult C. sinensis worms and bile ducts of rats

Extensively washed adult C. sinensis worms and the liver from the infected SD rats were fixed with 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Rat samples without infection were used as control. Slide sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and mounted onto glass slides. After inactivation of endogenous peroxidases, the slides were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h and then incubated with the murine immune sera or normal serum samples at room temperature for 1 h. After three washes, the slides were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rat IgG (Dako, CA, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing, the 3,3′diaminobenzidine reagent was incubated with the slides (tissue slices) for visualization of immunoreactivity. The slices were then counterstained with haematoxylin. Colour development on the slides was examined by light microscopy.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

This assay was carried out as described elsewhere (Jang et al. Reference Jang, Cho, Son, Lee, Lee, Lee and Seong2014). In brief, 96-well microplates (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA, 439454) were coated with 0.46 µg of purified hRID-CsAK3 or 3 µg of crude lysate of C. sinensis, P. westermani, Spirometra spp or C. cellulosae at 4 °C, overnight. Human serum samples were diluted 2500-fold in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 and 0.25% BSA, and the anti-human IgG antibody (Abfrontier, LF-SA5006) was diluted 16900-fold in the same buffer. The 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Fisher Scientific, NH, USA, BDB555214) was used for colorimetric reaction. The final result was obtained by subtracting the OD value from that of uncoated wells. ELISA was performed three times, independently.

Statistical analysis

The values in each graph represent means ± s.d. of the results, and Student's t-test was used to analyse statistical significance. A P value was considered statistically significant when it was lower than 0.05 (* for <0.05, and ** for <0.01).

Results

Signal peptide prediction and phylogenetic analysis of adenylate kinase 3

By analysis of the transcriptome DB CsUniDB v3.0, we identified CsTA805 as CsAK3. The protein was predicted as a secretory protein by Phobius analysis (Fig. 1A). The phylogenetic tree of adenylate kinase (AK) shows that CsAK3 shares high identity with AK3 of O. viverrini, and relatively low identity with AK3s of S. japonicum, S. mansoni or H. sapiens (Fig. 1B). Notably, homologous AK3s from other species, even the highly homologous O. viverrini, are not predicted to be secretory proteins (Fig. 1A) as deduced from the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1B). Considering the proven usefulness of ESPs for serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis (Kim, Reference Kim1998; Choi et al. Reference Choi, Park, Li and Hong2003; Li et al. Reference Li, Chung, Choi and Hong2004), the recombinant CsTA805, being identified as a secretory protein, could serve as a novel antigen for serodiagnosis.

The expression level of CsAK3 in each stage of C. sinensis was deduced from the CsUniDB v3.0. Transcriptome DB was highest in adult stage among three stages of life cycle (expression scores of CsAK3 in egg stage:metacercariae stage:adult stage = 0:2:6).

Recombinant protein design, cloning, expression and purification

Total RNA extracts were prepared from adult C. sinensis, and cDNAs were synthesized by reverse transcriptase with oligo-dT primers. The target gene was amplified by PCR. Two different versions of expression plasmids, for a wild-type form and for an hRID fusion form of CsAK3, were constructed (Fig. 2A). hRID is a tRNA-interacting domain, corresponding to the N-terminal 71 amino acids of human LysRS (Francin et al. Reference Francin, Kaminska, Kerjan and Mirande2002). As a prototype of the RNA interaction-mediated folding vehicle, the vector was designed for soluble expression of target proteins, based on the enhancement of folding and solubility by the interacting RNA molecule (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Han, Kim, Ryu, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kang, Shin, Lim, Kim, Hyun and Seong2008, Reference Choi, Ryu and Seong2009, Reference Choi, Lim and Seong2011, Reference Choi, Son, Lim, Jeong and Seong2012, Reference Choi, Kwon, Son, Jeong, Kim and Seong2013). Here, hRID was chosen as a fusion partner because of its small size and non-specific tRNA-binding ability (Francin et al. Reference Francin, Kaminska, Kerjan and Mirande2002), allowing for an interaction with E. coli’s resident tRNAs so as to assist folding in vivo in E. coli cytoplasm. Furthermore, hRID was expected to be relatively non-immunogenic in mice because of sequence similarity with the homologous domain of the mouse protein (74.6% of sequence identity). Thus, immunization of mice was expected to elicit antibodies predominantly to CsAK3 rather than to hRID. A 7-aa peptide, MSEQHAQ (ATGTCTGAACAACACGCACAG: DNA sequence), derived from LysRS of E. coli, was added to the N-terminal end of hRID, to ensure strong expression by enhancement of translation initiation (Qing et al. Reference Qing, Xia and Inouye2003).

Fig. 2. Expression and purification of CsAK3. (A) A diagram of the expression cassette. ‘Tev site’ represents recognition sequence of TEV protease, and ‘His tag’, six histidines as an affinity tag. (B) Proteins were expressed and analysed by SDS-PAGE. The lanes (T, S and P) represent a total extract, soluble fraction and pellet fraction, respectively. The target protein is shown with arrows. The fusion protein was detected by anti-his antibody. (C) The protein bands were semi-quantitated by densitometric scanning of the gel in Fig. 2B, and the relative solubility is shown as histogram. Vertical bars represent mean ± s.d., and a P value was considered statistically significant (* for <0.05, ** for <0.01) (D) hRID-CsAK3 was purified by single-step nickel affinity chromatography, dialysed, concentrated and quantified by gel densitometry using BSA as a standard. The purified protein was also detected by anti-his antibody.

After transformation of E. coli BL21*(pLysS) competent cells, protein was expressed. The hRID fusion greatly increased the solubility of CsAK3 (Fig. 2B,C). We also confirmed the expression of CsAK3 by Western blotting (WB). After initial screening for culture conditions for high soluble expression, the hRID-CsAK3 fusion protein was expressed at 30 °C, and the protein was purified by nickel affinity chromatography (final concentration: 9.2 mg mL−1; Fig. 2D). The production yield of hRID-CsAK3 (46 mg L−1) is ~3.2-fold greater than previously reported for glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-CsAK3 using GST as a soluble carrier (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Yu, Wu, Xu, Song, Zhang, Hu, Zheng, Guo, Xu, Dai, Ji, Gu and Ying2005).

Antiserum production and WB analysis

Three mice were immunized with a purified hRID-CsAK3 protein, and the serum samples were collected. The hRID-CsAK3 fusion protein was treated with TEV protease (Fig. 3A), and analysed by SDS-PAGE and by WB using the antisera from immunized mice (Fig. 3B). The results showed high specificity of the antisera to CsAK3, but not to hRID carrier, confirming that the hRID carrier itself is not immunogenic in mice, as expected from high sequence similarity to the murine counterpart. The normal serum samples as a negative control failed to react with the recombinant protein (Fig. 3B). Of note, the migration of hRID (MW 8.3 kDa) during SDS-PAGE was unusual, being located at a 17 to 18 kDa position (Fig. 3B). Expression of unfused hRID also revealed a similar pattern: hRID was located at 17–18 kDa (data not shown). The retardation of the migration velocity was not due to potential dimer formation, e.g. via disulfide bond formation even under reducing conditions of SDS-PAGE, because hRID does not carry any cysteine residues. The highly centred positive charge distribution of hRID may be responsible for retarded migration during SDS-PAGE, like some proteins, with unusual amino acid composition (Tompa, Reference Tompa2002). Anti-CsAK3 sera was also used to verify the presence of CsAK3 in crude lysate of adult C. sinensis. A band corresponding to 26 kDa was detected (Fig. 3C), confirming the expression of CsAK3 at the adult stage and specificity of anti-CsAK3 sera. Similar analysis also detected a clear-cut band of the expected size from ESPs. From the above results, we confirmed that CsAK3 was expressed and excreted at adult stage of C. sinensis as predicted.

Fig. 3. Western blot (WB) analysis of the obtained immune serum samples. (A) A diagram of cleavage of the hRID-CsAK3 fusion protein with TEV protease. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis before (−) and after (+) tev cleavage (M: size markers). The target proteins were visualized by Coomassie staining or WB (with immune serum or normal serum). The black and grey arrows indicate the location and the identity of proteins, respectively. (C) SDS-PAGE and WB analysis of a crude lysate and ESPs of adult C lonorchis sinensis.

Immunostaining of adult C. sinensis and bile ducts of C. sinensis-infected rats

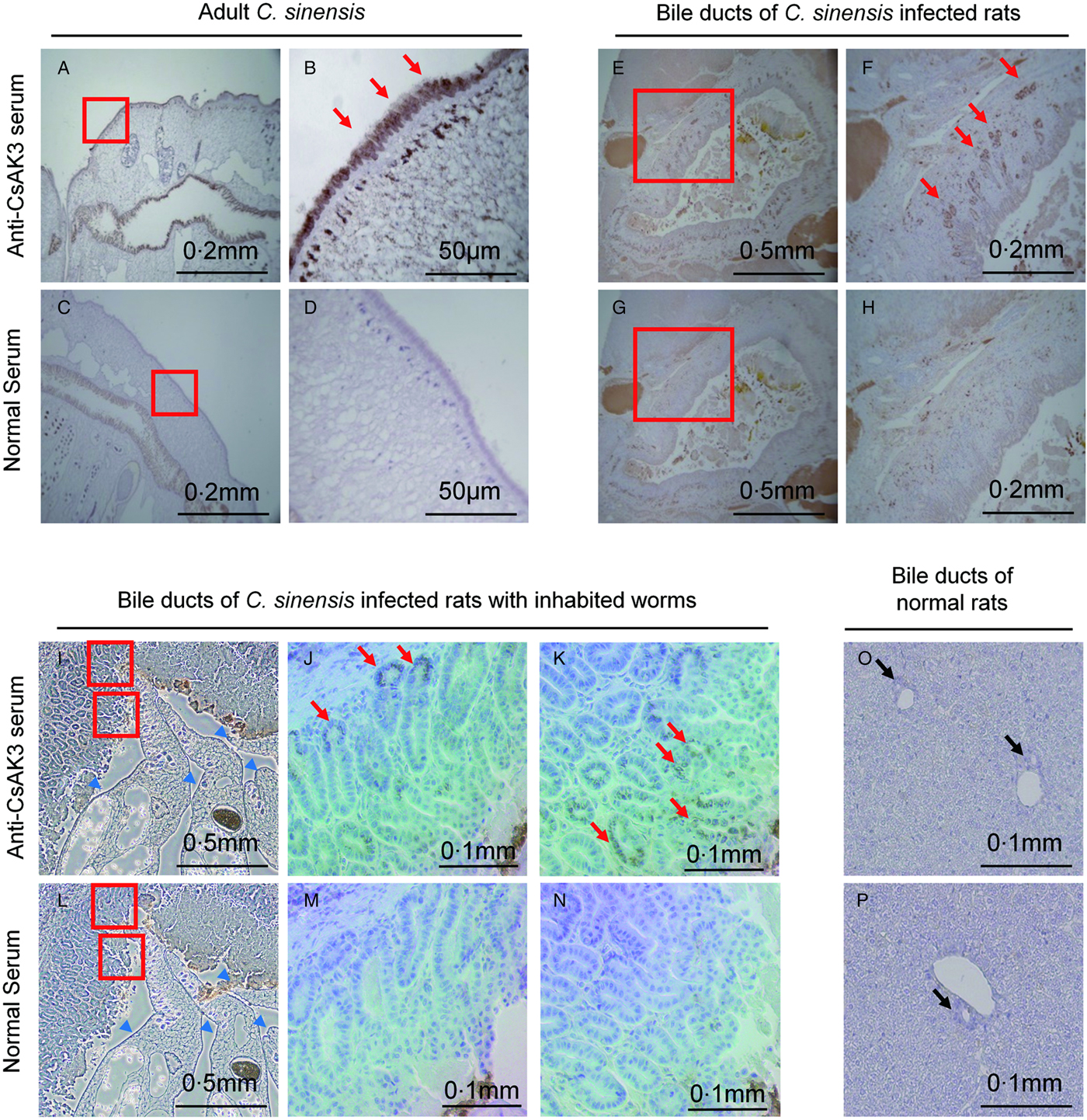

Confirming that CsAK3 was expressed at the adult stage of C. sinensis, we next investigated the localization of the protein in adult C. sinensis. Histochemical immunostaining using the antisera showed that CsAK3 was localized predominantly to subtegumental tissues (Fig. 4A,B), as compared with the negative control of normal mouse serum samples (Fig. 4C,D). Considering bile ducts as major habitats for C. sinensis (Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Zhu, Zhao, Wu, Okanurak and Lv2017), we then performed immunostaining of the bile ducts of C. sinensis-infected rats and uninfected rats. The bile ducts in C. sinensis-infected rats (Fig. 4E,G,I,L) appear to be enlarged as a physiological sign of infection as compared with that of uninfected rats (Fig. 4O,P), and there were inhabited adult worms of C. sinensis in bile ducts of infected rats (Fig. 4I,L). The CsAK3 protein was clearly detectable by anti-CsAK3 sera on the surface of bile ducts (Fig. 4E,F,I,J,K), in clear contrast to the controls (Fig. 4G,H,L,M,N,O,P). The results suggest that CsAK3 is indeed secreted as predicted and excreted in vivo, indicating a possible candidate antigen for serodiagnosis.

Fig. 4. Immuno-histochemical analyses of adult C lonorchis sinensis and bile ducts of C. sinensis-infected rats. Adult specimens of C. sinensis were analysed by immunostaining with (A,B) anti-CsAK3 mice serum, or (C,D) normal mice serum samples. Bile ducts of C. sinensis infected rats were analysed by means of (E,F,I,J,K) anti-CsAK3 serum or (G,H,L,M,N) normal murine serum samples. Blue arrow heads indicate inhabited adult worms in bile ducts of infected rats. Magnification of the areas of interest (red boxes) is shown at the right side of each figure (B,D,F,H,J,K,M,N). Red arrows indicate stained areas. As a control, bile ducts of normal rats were analysed either by means of (O) anti-CsAK3 serum, or (P) normal murine serum without immunization. Black arrows indicate bile ducts.

Serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis

We next tested whether the recombinant CsAK3 can serve an antigen for serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis. First, WB analysis was performed on the recombinant protein using the serum samples from C. sinensis-infected patients (positive serum) and healthy persons (negative serum). Positive serum detected a clear-cut band, specifically of the target size (Fig. 5A). Recombinant CsAK3 or crude lysates were also used as coating antigens on a microplate for an ELISA assay, using the serum samples from C. sinensis-infected patients and healthy persons (Fig. 5B). The ELISA assay was performed in two independent experimental settings: set1 comprising six and two independent samples of positive and negative sera, respectively, and set2 comprising eight and five independent samples of positive and negative sera, respectively. Overall, using the CsAK3 recombinant antigen, the ELISA positivity rate was 64% (9/14) in the positive sera, in contrast to zero value (0/7) in the negative serum samples. The control experiment using the crude lysates as coating antigen showed the ELISA response of (14/14) in the positive serum samples and (0/7) in the negative serum samples.

Fig. 5. Serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis by means of purified recombinant CsAK3 and a crude lysate. (A) SDS-PAGE and WB analysis of purified recombinant hRID-CsAK3 using serum samples from a C lonorchis sinensis-infected patient (positive serum) and a healthy person (negative serum). (B) ELISA, involving purified recombinant CsAK3 and a Cs lysate as coating antigens, was performed in two independent experimental settings: set1 comprising six and two independent positive (P) and negative (N) sera, and set2 comprising eight and five independent positive and negative sera, respectively. Horizontal lines represent cut-off values (mean of negative sera + 3 × s.d. of negative sera). (C) Cross-reaction with sera from other parasites. Sera from Paragonimus westermani (PW), Spirometra spp (Sp) or Cysticercus cellulosae (Cyst) infected patients, and negative sera from healthy people (N) were assayed. PW lysate, Sp lysate, Cyst lysate, Cs lysate and recombinant CsAK3 were used as a coating antigen.

We then examined potential cross-reaction of CsAK3 with serum samples from other parasites: P. westermani, Spirometra spp and C. cellulosae (Fig. 5C). We confirmed that there were no or a little cross-reaction with other parasites: (0/9) for P. westermani, (0/9) for Spirometra spp and (1/10) for C. cellulosae. The Cs lysates, however, exhibited higher cross-reaction with the parasites, (8/9), (6/9) and (1/10) for P. westermani, Spirometra spp and C. cellulosae, respectively. The results show that the recombinant CsAK3 could replace Cs lysates for specific serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis.

Discussion

CsAK1 has been previously identified as a potential serodiagnosis target antigen for C. sinensis infection (Liang et al. Reference Liang, Zhang, Chen, Hu, Huang, Li, Ren, He, Li, Li, Xu, Wu, Lu and Yu2013b). The isotype CsAK3 was also discovered and its biochemical activities characterized (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Yu, Wu, Xu, Song, Zhang, Hu, Zheng, Guo, Xu, Dai, Ji, Gu and Ying2005), but its histochemical properties and potential use as a serodiagnosis target antigen has not been investigated. In this study, CsAK3 was expressed in soluble form in E. coli and purified, and antisera were raised by mouse immunization, then immunohistochemical analyses of C. sinensis were performed. We next validated and confirmed its potential as a serodiagnosis target antigen by an ELISA using serum samples from C. sinensis-infected patients.

Here, we employed an RNA interaction-mediated protein-folding vehicle for soluble expression of CsAK3. This system utilizes an RNA-interaction domain as a folding and solubility enhancer, where the RNA molecule performs the chaperone function (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Han, Kim, Ryu, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kang, Shin, Lim, Kim, Hyun and Seong2008, Reference Choi, Ryu and Seong2009, Reference Choi, Lim and Seong2011, Reference Choi, Son, Lim, Jeong and Seong2012, Reference Choi, Kwon, Son, Jeong, Kim and Seong2013; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Choi and Seong2010b; Docter et al. Reference Docter, Horowitz, Gray, Jakob and Bardwell2016). The chaperna (RNA-mediated chaperone function) was originally described in viral infections (HIV TAR RNA-tat folding system) (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Choi and Seong2017) and in an E. coli ribozyme (M1 RNA-C5 protein folding) (Son et al. Reference Son, Choi, Han and Seong2015), and here, was extended in a designer ‘immunologically tailored’ antigen expression system. Unlike the previously reported case of LysRS (Lys-tRNA synthetase of E. coli origin), which is well structured and relatively large in size (~57 kD) (Desogus et al. Reference Desogus, Todone, Brick and Onesti2000), hRID is small (~8 kD) and contains an unstructured region (Yiadom et al. Reference Yiadom, Hammamieh, Ukpabi, Tsang and Yang2003). Despite such differences, both proteins interact with tRNAs: Lys-tRNA specifically for LysRS and non-specific tRNAs for hRID, respectively (Francin et al. Reference Francin, Kaminska, Kerjan and Mirande2002; Choi et al. Reference Choi, Han, Kim, Ryu, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kang, Shin, Lim, Kim, Hyun and Seong2008). Besides the profound usefulness of the folding vehicle for obtaining soluble proteins, considerations should be given to the choice of the fusion partner, especially for the preparation of antigens with a view to raise specific antibodies for diagnostic purposes and histochemical analyses. Unlike LysRS of bacterial origin, hRID of human origin is highly homologous with its rodent counterpart (sequence similarity 74.6%), and therefore, is relatively non-immunogenic during mouse immunization (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the antisera against the hRID-CsAK3 fusion protein are specific for CsAK3 without cross-reaction with the hRID domain, thereby minimizing non-specific signals and increasing the specificity of detection (Fig. 3B). A dual use of the chaperna function not only as chaperones but as an immunologically tailored folding vehicle should greatly extend the repertoire of target antigens amenable to diagnostic applications.

Here, we predicted in silico that CsAK3 is a secretory protein, and confirmed that CsAK3 is indeed excreted into bile ducts of C. sinensis-infected rats (Fig. 4E,F,I,J,K). Expression of CsAK3 in subtegumental tissues at the adult stage was verified by immunostaining (Fig. 4A,B). The potential as a serodiagnosis target antigen was also confirmed by WB and an ELISA (Fig. 5). Although the crude lysate from adult C. sinensis manifested better sensitivity than purified recombinant CsAK3 as a serodiagnosis target antigen, it showed cross-reactivity with C. sinensis-related parasites (Fig. 5C) (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Park, Li and Hong2003). In content, virtual lack of cross-reaction against other related parasites underscores the utility of recombinant CsAK3 for specific diagnosis of C. sinensis infection. Moreover, the preparation of a crude lysate requires the culture and purification of C. sinensis from experimentally infected animals; this work is laborious and time-consuming. Instead, the recombinant antigen could be produced in a bacterial host with a high yield and purity by well-established standardized procedures. The sensitivity of diagnosis via recombinant CsAK3 could be augmented by combination with other previously identified antigens, e.g. CsAK1 (Liang et al. Reference Liang, Zhang, Chen, Hu, Huang, Li, Ren, He, Li, Li, Xu, Wu, Lu and Yu2013b), CsTMX (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Bian, Liao, Mao, Li, Zhou, Wang, Li, Liang, Li, Huang and Yu2013), CsFBPase (Liang et al. Reference Liang, Sun, Huang, Zhang, Zhou, Hu, Wang, Liang, Zheng, Xu, Mao, Hu, Li, Xu, Lu and Yu2013a), CsSTK17A (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Lv, Huang, Hu, Yan, Zheng, Zeng, Li, Liang, Wu and Yu2014) or CsNOSIP (Bian et al. Reference Bian, Li, Wang, Xu, Chen, Zhou, Chen, He, Xu, Liang, Wu, Huang, Li and Yu2014), thereby enhancing the robustness of the diagnostic tool for clonorchiasis.

In conclusion, CsAK3 was identified and validated as a new candidate for a serodiagnosis antigen. CsAK3 was successfully generated in soluble form by means of a robust chaperna-based immunologically tailored folding vehicle wherein the RID domain was judiciously chosen to minimize cross-reactions. The results warrant the validation of its utility as serodiagnosis of clonorchiasis by further increasing the member of infected serum samples. The present results are expected to improve the clinical diagnosis of clonorchiasis and provide a user-friendly technical platform for the preparation of diagnostic antigens from a repertoire of infectious agents.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank Division of Malaria and Parasitic Diseases, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) for providing CsUniDB v3.0 and analysing the DB.

Financial support

This work was supported by the grants from Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant number 2014-E54007-00); Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare (grant numbers HI13C0826, HI15C2934).