Introduction

Technological breakthroughs are often the product of scientific knowledge, and can in turn provide new tools for scientific advances. For instance, technology has empowered the study of life, from the invention of the microscope to the latest developments in genomics, imaging and GPS tracking technology. If biologists make rational and unconstrained decisions about what they study, we might expect that research effort would be allocated to different types of organisms in proportion to their diversity and abundance, their accessibility, their importance to society or to scientific progress, and how much funding they are likely to attract. However, much evidence exists to show that this is not always the case, and that allocation of research effort to different taxa is biased in many other ways (e.g. Hendriks and Duarte, Reference Hendriks and Duarte2008; Ahrends et al., Reference Ahrends, Burgess, Gereau, Marchant, Bulling, Lovett, Platts, Kindemba, Owen, Fanning and Rahbek2011; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Blossey and Ellis2012). This may also be reflected in the adoption of technological breakthroughs, with new research tools applied earlier and more frequently to certain taxa than others. In this synthesis, we examine discrepancies in the temporal deployment of new molecular methodologies toward the study of parasitic vs non-parasitic organisms, explore the possible reasons underlying the observed differences, and look ahead to the near future of molecular research on parasites.

A priori, there should be no reason why the application of molecular tools to parasitic organisms should have followed a different trajectory than their application to non-parasites. Most estimates agree that nearly half the living species are parasites, and that every free-living species (except perhaps some small unicellular taxa) harbours parasites (Windsor, Reference Windsor1998; Dobson et al., Reference Dobson, Lafferty, Kuris, Hechinger and Jetz2008; Poulin, Reference Poulin2014). Parasites are phylogenetically diverse, having evolved independently over 200 times among metazoan lineages alone (Weinstein and Kuris, Reference Weinstein and Kuris2016). They occur in all types of environment, surpassing their hosts in absolute abundance, and have been shown to play major roles in host population dynamics (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Dobson and Newborn1998; Tompkins et al., Reference Tompkins, Dobson, Arneberg, Begon, Cattadori, Greenman, Heesterbeek, Hudson, Newborn, Pugliese, Rizzoli, Rosà, Rosso, Wilson, Hudson, Rizzoli, Grenfell, Heesterbeek and Dobson2002; Møller, Reference Møller, Thomas, Renaud and Guégan2005), community structure (Mouritsen and Poulin, Reference Mouritsen and Poulin2005; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Byers, Cottingham, Altman, Donahue and Blakeslee2007; Hatcher and Dunn, Reference Hatcher and Dunn2011), food web stability and energy flow (Kuris et al., Reference Kuris, Hechinger, Shaw, Whitney, Aguirre-Macedo, Boch, Dobson, Dunham, Fredensborg, Huspeni, Lorda, Mabada, Mancini, Mora, Pickering, Talhouk, Torchin and Lafferty2008; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Allesina, Arim, Briggs, De Leo, Dobson, Dunne, Johnson, Kuris, Marcogliese, Martinez, Memmott, Marquet, McLaughlin, Mordecai, Pascual, Poulin and Thieltges2008; Selakovic et al., Reference Selakovic, de Ruiter and Heesterbeek2014; Preston et al., Reference Preston, Mischler, Townsend and Johnson2016). Parasites also have huge impacts on human health. Great white sharks, venomous snakes and killer bees make the headlines, but parasites kill orders of magnitude more people every year, and cause debilitating diseases in an even greater number of people (Torgerson et al., Reference Torgerson, Devleesschauwer, Praet, Speybroeck, Willingham, Kasuga, Rokni, Zhou, Fèvre, Sripa, Gargouri, Fürst, Budke, Carabin, Kirk, Angulo, Havelaar and de Silva2015). Parasites are also responsible for reduced production and huge economic losses in livestock farming (Rist et al., Reference Rist, Garchitorena, Ngonghala, Gillespie and Bonds2015), and pose serious challenges to conservation biologists and wildlife managers striving to protect the free-living species we cherish the most (Lafferty and Gerber, Reference Lafferty and Gerber2002; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Acevedo-Whitehouse and Pedersen2009).

Parasites are therefore arguably as (if not more) diverse, ubiquitous and important as non-parasitic organisms. When new research tools become available, one would thus expect them to be applied to parasites no later than, and as frequently as, they are applied to non-parasites. For instance, the last several decades have witnessed the rapid expansion of molecular technologies as a means to explore the genetic basis of life. Molecular methods are now part of the standard toolkit of scientists in fields as diverse as evolutionary biology, taxonomy, ecology, developmental biology, immunology, medicine, and of course genetics. The growth of molecular technology has been regularly punctuated by major advances and their rapid conversion into usable tools. The molecular genetics era can be split into three distinct periods, each characterized by its own set of methods, analytical or statistical approaches and possibilities (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Snow, Schug, Booton and Fuerst1998; Schlötterer, Reference Schlötterer2004; Metzker, Reference Metzker2005; Schuster, Reference Schuster2007; Metzker, Reference Metzker2009). First, in the allozyme period, one could quantify differences in amino acid composition between enzymes from different individuals or species, as a proxy for genetic variation. Second, in the nucleotide sequencing period, it became possible and relatively simple to obtain actual DNA sequences for multiple genes, greatly expanding our window into an organism's genetic blueprint. Finally, in the genomics period, it is now possible to sequence entire genomes, as well as the transcriptomes, of living organisms, providing a complete picture of their genetic underpinnings.

These developments have provided researchers with an arsenal of new tools to explore the biology of parasites and non-parasites alike. Whereas there is no reason why these should be applied earlier or more frequently to either type of organisms, among parasites we may expect new molecular methods to be first used to study human parasites before they are applied to parasites of other organisms, simply because there is more funding and greater urgency to investigate the former in order to reduce human suffering. Furthermore, among both human parasites and those of other organisms, molecular tools may be applied disproportionately more to certain taxa than others, due to differences in diversity or perceived importance.

Here, we use empirical evidence from the scientific literature to test quantitatively the general hypothesis that the application of molecular tools to study parasites follows the same temporal profile as their application to the study of non-parasites. Also, among parasites, we test the hypothesis that new molecular tools are first adopted and used more extensively to study medically important species than any other type of parasites. More specifically, we answer the following questions: (i) Are new molecular tools adopted at the same time for the study of parasites and non-parasites, and if not, what is the time difference? (ii) How much of the early adoption of new molecular approaches is driven by research on medically important parasites? (iii) What are the most common topics of parasitological research using molecular approaches, and did these stay the same across the three periods of molecular research (allozyme, nucleotide, genomics)? (iv) What are the most commonly studied parasite taxa? and (v) What is the geographical distribution of molecular parasitological research? Our review provides a historical overview and illustration of the growth and development of molecular parasitology, as well as an exploration of the cultural differences between parasitologists and biologists studying non-parasites. We conclude with central take-home messages and recommendations for the future growth of parasitological research to assess the ecology and evolution of these phylogenetically diverse and ecologically important organisms.

Materials and methods

Data search and compilation

In order to analyse the research output on parasites in the molecular era, we identified and characterised three distinct periods of molecular research: the allozyme period, the nucleotide period and the genomics period. The ‘allozyme period’ is characterised by the use allozyme techniques (i.e. analysing differences in enzyme structure between organisms) that were established in the 1960's (Hubby and Lewontin, Reference Hubby and Lewontin1966; Schlötterer, Reference Schlötterer2004). First conceived in the 1970's–1980's but popularised in the 1990's, the ‘nucleotide period’ is largely characterised by the use of Sanger sequencing and microsatellites (Sanger et al., Reference Sanger, Air, Barrell, Brown, Coulson, Fiddes, Hutchison, Slocombe and Smith1977; Litt and Luty, Reference Litt and Luty1989; Mathies and Huang, Reference Mathies and Huang1992; Richard et al., Reference Richard, Kerrest and Dujon2008) and a small number of markers to distinguish between DNA sequence variations. Finally, the ‘genomic period’ is characterised by the onset of next generation sequencing (Solexa, 454, Illumina, SOLiD, etc.) established after 2005 (Bennett, Reference Bennett2004) and use of large datasets frequently utilising 1000s of markers on multiple genomic loci or whole genomes. Although treated as somewhat discrete periods in this study, in reality they are interwoven and overlap in time. For example, many genomes were initially sequenced using Sanger sequencing in the 1990s, but here whole genome research is classed as part of the genomic period.

For each period, we chose a set of keywords (see Supporting File S1) that captures the molecular markers, tools and methods developed and utilized in this context. We examined and compiled data on the publication trends of molecular research in these three periods by conducting a detailed search on the Web of Science™ for all entries until November 2018. In order to only capture relevant publications from the respective periods, we excluded the succeeding period(s) from the searches, e.g. when searching for the nucleotide period, we excluded search terms belonging to the genomics period. Moreover, the searches were restricted to relevant categories (i.e. biological, environmental, medical sciences, etc.), and to peer-reviewed research articles or reviews. For the analyses of publication trends in overall biological research (i.e. research on parasites and non-parasites together) within each period, we downloaded only the numbers of publications per year.

We then performed the same search for each molecular era, with the addition of a range of search terms for parasitic organisms to capture the majority of parasite-related publications within the three molecular periods. Although we did not include bacteria, fungi or viruses in these parasite-search terms, we did not exclude those groups specifically. For the analyses of publication trends on parasitic organisms, we downloaded the full records for all parasite-related publications from each molecular period (including title, abstract, keywords, author country, publication date and journal). The individual search terms for all molecular periods, the specific parasite-search terms and the Web of Science categories are presented in Supporting File S1.

Analyses

All analyses were performed in R (R Core Team, 2018). Data from the searches was imported into R using the bibliometrix package (Aria and Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). To determine what proportion of parasitology research is comprised of medically relevant parasites, we set up two categories of parasitological research, ‘all parasites’ and ‘medical parasites’. All parasites contained the raw parasite data as downloaded from Web of Science. The second group, ‘medical parasites’, contained all the papers from within the all parasite group which were categorised as being medically focused. Assignment to the medically focused category was done by searching across the papers' abstracts, titles and keywords for a list of terms associated with either humans (e.g. human, man, woman) or human-related pathogens and diseases (e.g. Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, lyme disease). Details of the terms are available in Supporting File S2. This resulted in three datasets across the three periods: ‘general’, ‘all parasites’ and ‘medical parasites’.

To compare when and how fast new techniques were adopted across the three datasets, research publication trends within each era and group (‘general, all parasites, medical parasites’) were analysed from 1960–2017 by plotting the number of publications over time. To determine whether research focus had shifted across the three periods within parasitological research (‘all parasites’), we generated word clouds and networks using publication keywords. Keywords were first cleaned to avoid duplications due to abbreviations (e.g. PCR and polymerase chain reaction) or pluralisation (e.g. tick and ticks). For the word clouds, we also removed all our search terms (e.g. ‘nucleotide sequencing’), taxa or disease names (e.g. ‘malaria’ or ‘Plasmodium’) and molecular markers (e.g. ‘COI’). Word clouds were then generated using the top 40 keywords across each period in the wordcloud package in R (Fellows, Reference Fellows2018). Networks for each period were generated using the ggplot2 and ggraph packages in R (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016; Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2018). Within each of the three periods, keyword pairs or words that occur together within an individual article's keywords were summed across all articles. Networks for each period were generated using the top 100 keyword pairs that had a minimum of three counts. To analyse which groups of parasites are most commonly studied using molecular tools, we quantified the proportion of papers published per taxonomic group within parasitological research (‘all parasites’) using a Sankey plot generated via plotly in R (Sievert, Reference Sievert2018). The focal taxon (or taxa) for each paper was determined by searching for taxa names across article description fields (title, abstract, keywords). Papers that mentioned more than one taxonomic group in the description fields were either reassigned to a single category (e.g. studies on arthropods as a vector of Leishmania were assigned to the latter), or classified as ‘multiple species’ (e.g. studies on both cestodes and trematodes were assigned to ‘helminths’ but not divided further). Finally, to visualize the geographic distribution of parasite research, world maps were generated for each molecular period with the R package rworldmap (South, Reference South2011). For each publication the respective country of origin was defined according to the affiliation of the corresponding author.

The R code for all analyses is available in Supporting File S2.

Results

The database search on the three periods of molecular research resulted in a total of 1.33 million publications, the majority of which appeared during the nucleotide period (Table 1). Studies on parasitic organisms constituted less than five percent of the total research output and were lowest in the genomics period.

Table 1. Number of publications in the three periods of molecular research

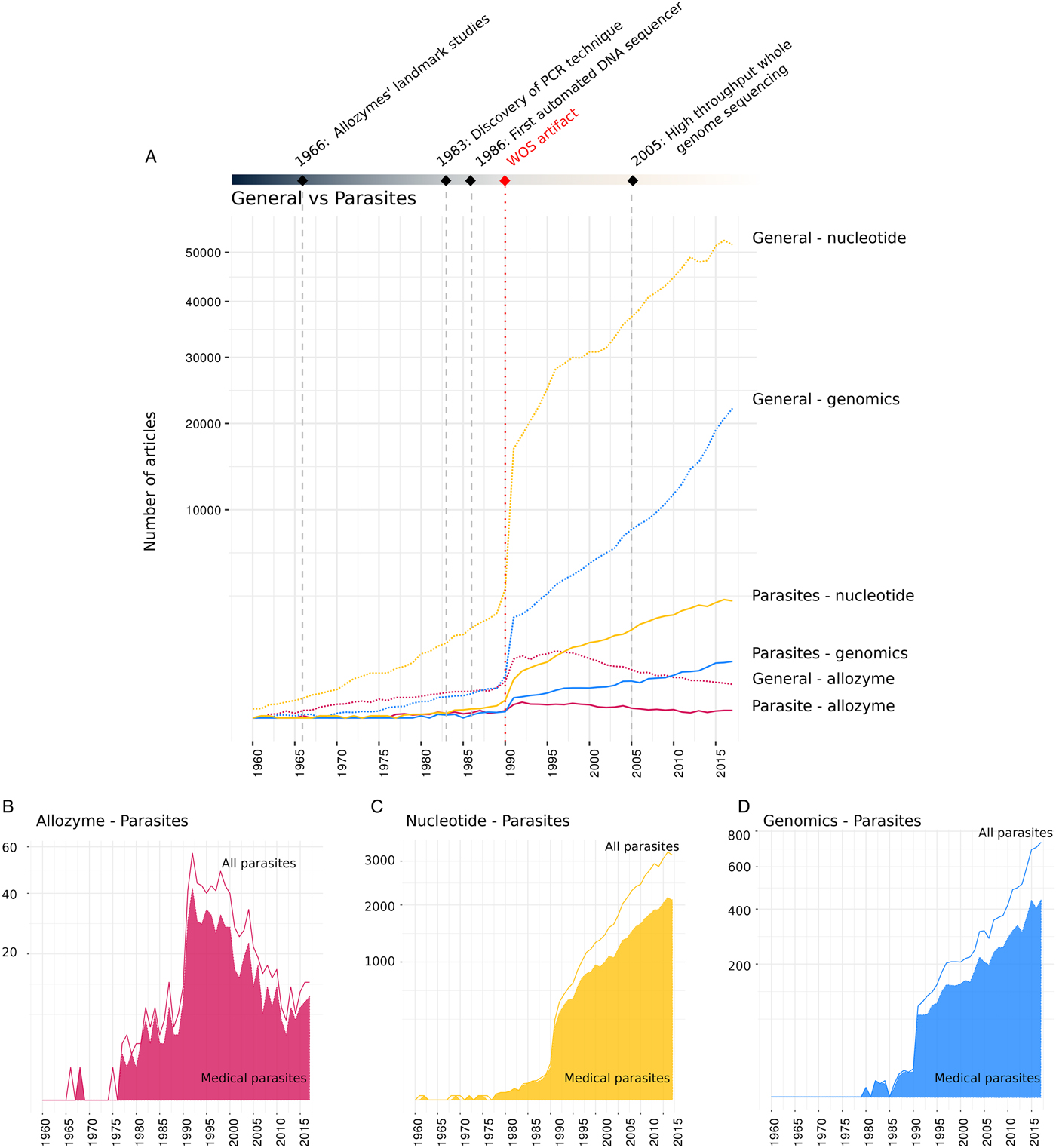

The temporal publication trends show that parasite research in each molecular period followed the same overall patterns as the general output over the years (Fig. 1A). The sudden jump in publication numbers from 1990 to 1991 is an artefact of the Web of Science search algorithm (see Pautasso, Reference Pautasso2014) and does not allow an accurate comparison of pre- and post-1990 publication patterns. However, since we are interested in the differences between overall publication trends and subsets of these datasets (studies on parasites and medically relevant parasites), and the artefact applies to all these groups equally, this does not distort our analyses. Post 1990, publication output in the nucleotide and genomics periods continually increased, while the allozyme dataset revealed a decreasing publication trend. Parasite research output followed these general trends but at a slightly more conservative rate, i.e. they show a slower increase in the nucleotide, and a slower decline in the allozyme periods (see Supporting Fig. S3). Within the parasite subsets across all periods, medically relevant parasites dominate the research output, making up 65–70% of publications. Across all periods of molecular research, early publications almost exclusively comprise studies on medically relevant parasites (Fig. 1B–D); the larger nucleotide and genomics datasets show that research on non-medical parasites only appears in reasonable numbers after a delay of several years, and starts to slowly increase thereafter.

Fig. 1. Number of studies published during the three molecular periods from 1960 to 2017 (research articles and reviews). (A) General research output and parasite-related publications in each period; (B) Output of publications on parasites and medically relevant parasites in the allozyme period; (C) Output of publications on parasites and medically relevant parasites in the nucleotide period; (D) Output of publications on parasites and medically relevant parasites in the genomics period. The sudden jump in publication numbers from 1990 to 1991 is an artefact of the Web of Science search algorithm (see results).

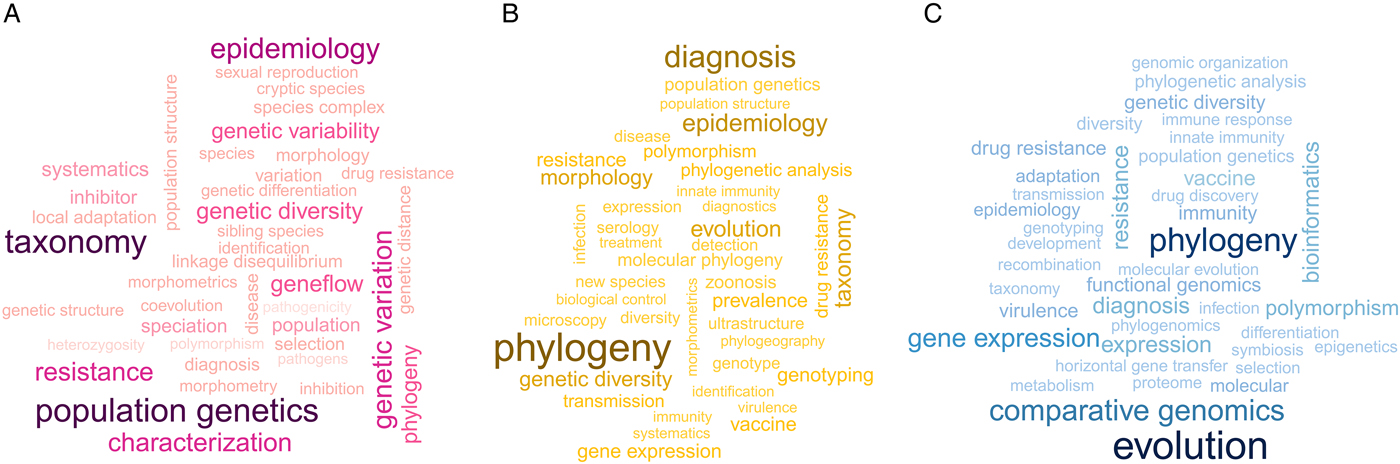

Word clouds and networks of publication keywords show the predominant research fields and topics of parasitological research using the three molecular approaches (Figs 2 and 3; see Supporting File S4 for a large version of Fig. 3). Across the three periods, there is a shift in the main focus of research from discovery and taxonomy in the allozyme period to phylogeographic and disease diagnosis in the nucleotide period, to finally evolutionary genetics and comparative genomics in the genomic period. A large proportion of the top words in all periods are directly related to medical research, e.g. epidemiology, diagnosis. The most interconnected terms within the networks are related to the techniques that define each period (e.g. allozyme, polymerase chain reaction, genomics). In contrast with the later periods, medical research in the allozyme period focuses largely on Leishmania with no reference to Plasmodium and malaria.

Fig. 2. Word clouds highlighting the most common research fields in the individual molecular periods. (A) Allozyme period; (B) nucleotide period; (C) genomics period. The more frequently a term is used in the keywords, the larger and darker it is shown in the word cloud.

Fig. 3. Semantic networks for the individual molecular periods. (A) Allozyme period; (B) nucleotide period; (C) genomics period. Networks are based on terms used in the keywords. The more frequently terms co-occur within the same paper, the bolder and darker the connecting lines (see individual legends). Nodes that represent medically relevant terms are highlighted in orange.

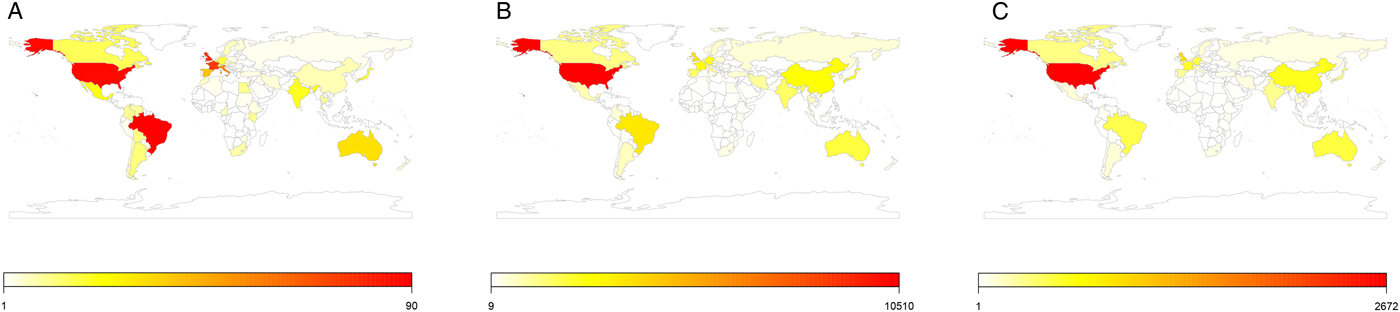

The Sankey plot reveals the most commonly studied parasite taxa from all periods and illustrates the strong research focus on protist parasites, in particular Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, Leishmania, and Toxoplasma (Fig. 4, see Supporting File S5 for an interactive version of the figure). While research on protists remains dominant across all periods, there is a shift in its relative contribution from 56% in the allozyme period to 45 and 41% in the nucleotide and genomics period, respectively, while research interest in other parasite groups increases (e.g. arthropods, multiple species). The analysis of the geographical distribution of molecular parasitological research shows the vast majority of publications originate from the United States, with the exception of research during the allozyme period where Brazil and Europe were considerable contributors (Fig. 5, see Supporting File S6 for an interactive version of the figure). Although the United States remains the highest contributor, within the last 10 years, particularly the last 2 years, a growing number of publications originate from China within both the nucleotide and genomic periods.

Fig. 4. Sankey plot showing the parasite taxa studied using molecular methods. The thickness of each line represents the relative number of publications on that particular taxon.

Fig. 5. Maps showing the publication output (research articles and reviews) during the three molecular periods from 1960 to 2017. (A) Allozyme period; (B) nucleotide period; (C) genomics period. Based on the affiliation of the corresponding author.

Discussion

Since parasites play central roles in all ecosystems and their evolutionary trajectory is closely linked with that of their hosts, research on parasitic organisms is central to our understanding of most fundamental biotic interactions and concepts. Parasitic life styles have evolved multiple times, and parasitic organisms are estimated to account for 30–50% of global biodiversity (Windsor, Reference Windsor1998; Dobson et al., Reference Dobson, Lafferty, Kuris, Hechinger and Jetz2008; Poulin, Reference Poulin2014; Weinstein and Kuris, Reference Weinstein and Kuris2016). We therefore hypothesized that new molecular tools would be applied to parasites no later than, and as frequently as, they are applied to non-parasites.

Our results suggest a more complex picture. Only less than 5% of the 1.3 million publications in our dataset deal with parasitic organisms. Moreover, within these publications on parasites, almost 70% of the studies focused on medically relevant taxa. In particular, protists of the genera Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, Leishmania, and Toxoplasma, as well as mites and ticks (Acari) and the disease agents transmitted by these vectors, have been the predominantly studied parasite groups. Other important disease agents attract far less attention. In fact, the molecular research output on Plasmodium alone (10 800 publications) exceeds the combined publication volume on all helminths (10 600 publications). Likewise, not all so-called neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) receive similar research attention; while Trypanosoma (3750 publications), Leishmania (2930 publications) and Schistosoma (2100 publications) are relatively well-studied groups, other pathogens, such as Ascaris and hookworms receive far less attention (550 and 200 publications, respectively), despite more than a quarter of the world's population being at risk of infection with these soil-transmitted helminths (Jourdan et al., Reference Jourdan, Lamberton, Fenwick and Addiss2018). Overall, these publication trends in molecular research on parasites seem to support recent findings that research effort on different parasitic pathogens does not reflect the actual human disease burden they inflict, and highlights that some medically relevant taxa remain severely understudied (Furuse, Reference Furuse2019).

Beyond this uneven research focus within the group of medically important parasites, our results show that the vast majority of parasite species are not studied with these molecular tools, regardless of whether the true diversity of parasitic organisms is closer to the higher or lower end of current diversity predictions (see Poulin, Reference Poulin2014). Due to the large dataset with over one million published articles and similar relative numbers of medically relevant parasites across all periods of molecular research, we believe our results are representative of the general trends in parasite research. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to see if this discrepancy between predicted biodiversity of parasites and research output, as well as the strong focus on medically important taxa, are similarly pronounced for other methodological approaches, such as electron microscopy and modern imaging technologies.

The comparison of general and parasite-related publication output in the scientific literature indicates some dissimilarities in the temporal trends, i.e. in the nucleotide period, parasite research output showed a slower increase relative to the general field, whereas the output in the allozyme period decreased at a slower rate than the general field. This might suggest that parasite research is slightly more conservative in using these molecular tools. It could be that the way in which parasitologists were trained led to possible cultural differences between them and biologists studying non-parasites, influencing their willingness to adopt new techniques from other fields. However, it must be noted that no difference was apparent in the rapidly developing genomics field.

Given the substantial global burden parasitic diseases impose on humanity (see GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2016), it is not surprising that new molecular methods are first used to study these medically relevant parasites, in order to better understand their biology and distribution, and develop control approaches, treatments and vaccines to reduce human suffering. While during the 1990s, cost per megabase (mb, i.e. a million bases) exceeded 10 000 USD and initial genome projects ran into the hundreds of millions (the human genome project alone is estimated at 2.7 billion USD), recent years have seen the cost of sequencing drastically reduced (2017 estimate <0.1 USD per mb) (Hall, Reference Hall2013; National Human Genome Research Institute, 2018). Moreover, beyond sequencing costs, the increasingly complex datasets in the genomics period require thorough bioinformatic analyses that needed to become more accessible (Muir et al., Reference Muir, Li, Lou, Wang, Spakowicz, Salichos, Zhang, Weinstock, Isaacs, Rozowsky and Gerstein2016). This would explain why, in both the nucleotide and genomics periods, it took years for research on parasites other than medically important ones to get started.

We were interested in finding out what topics parasitological research addresses using molecular approaches, and whether these stayed the same across the three periods of molecular research. The word clouds reveal a gradual shift from predominantly species discovery (taxonomy and population genetics) during the allozyme period to studying the relationships among various species (phylogeny) during the nucleotide period, and finally addressing broader theory-focused questions (evolution) in the genomics period. Correspondingly, the networks suggest an increasing complexity of topics and research questions addressed with more sophisticated methods from the allozyme to the genomics period. Additionally, the networks reveal more detailed changes in the application and research foci of the different molecular methods. While medical research in the allozyme period focuses largely on Trypanosoma and Leishmania with no reference to malaria, the later nucleotide sequencing and genomics periods show a greater diversity of disease-related studies, most likely due to the larger number of studies in the datasets, and a strong emphasis on Plasmodium and malaria research.

The distinctive cluster in the nucleotide era network (Fig. 3B) that links the keywords ‘morphology', ‘taxonomy’ and ‘phylogeny’ highlights the common use of integrative molecular and morphological approaches to identify and describe new parasite species. Indeed, ‘integrative taxonomy’ has replaced classical taxonomy in the early 2000s, right in the middle of the nucleotide period (Dayrat, Reference Dayrat2005). Nucleotide sequencing approaches (e.g. barcoding) have become practical, reliable and cost-efficient tools to address these issues and uncover hidden and cryptic parasite diversity in ecosystems (e.g. Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Selbach et al., Reference Selbach, Soldánová, Georgieva, Kostadinova and Sures2015). Moreover, many parasites have complex life cycles with morphologically highly distinct stages in different hosts; these stages are therefore difficult to match and assign to the same species (Poulin and Leung, Reference Poulin and Leung2010; Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin and Marcogliese2013). Consequently, many parasite life cycles are not yet fully described, and modern molecular tools are proving invaluable to resolve life cycles (e.g. Jensen and Bullard, Reference Jensen and Bullard2010; Blasco-Costa et al., Reference Blasco-Costa, Poulin and Presswell2016). Since much of parasite diversity is still unknown and our discovery efforts lag well behind our knowledge of free-living diversity (see Jorge and Poulin, Reference Jorge and Poulin2018), these well-established molecular approaches are helping to close this gap.

Despite the global disease burden caused by many parasite taxa, the geographical distribution of molecular parasitological research is highly uneven. Across all three periods, the research landscape is dominated by a few individual countries, in particular the United States. Only the allozyme period shows a wider distribution with Brazil and Europe (France and the United Kingdom) contributing markedly to the overall research output. The higher number of studies from Brazil can likely be explained by the strong research focus of allozyme studies on Leishmania spp. and Trypanosoma cruzi that cause leishmaniasis and Chagas disease, respectively. Both represent important public health problems in Brazil, with Chagas disease alone resulting in an average of 5000 deaths per year (Alvar et al., Reference Alvar, Vélez, Bern, Herrero, Desjeux, Cano, Jannin and den Boer2012; Ferro e Silva et al., Reference Ferro e Silva, Sobral-Souza, Vancine, Muylaert, de Abreu, Pelloso, de Barros Carvalho, de Andrade, Ribeiro and de Toledo2018). It must be noted however that our assessment of the geographical distribution of research is based on the affiliation of the corresponding author and therefore typically shows the origin of the funding rather than the study region or the location of collaborators (e.g. a study on malaria vectors in Venezuela by a senior author based at a research institute in the United States will be associated with the latter). Although scientific instruments, such as thermocyclers and sequencers, have become more readily available and cheaper and the overall costs for molecular analyses have decreased, in less economically developed regions such equipment and consumables often remain highly expensive (see van Helden, Reference Van Helden2012), making it even harder for researchers in these countries to utilize molecular tools.

With countries in other regions, especially China in East Asia, increasing their research and development expenditure (UIS, 2019; World Bank, 2019) and many of the world's largest genomic institutes and projects, e.g. Beijing Genomics Institute and Genome Asia 100k, being focused on Asia, we expect a further shift in these patterns in the future. Looking at the research output from the last five years supports this and reveals a strong increase in publications from China in the nucleotide and genomics fields. Moreover, since some major parasitic disease agents, such as Schistosoma japonicum (Gryseels et al., Reference Gryseels, Polman, Clerinx and Kestens2006; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guo, Wu, Chen, Wang, Zhu, Zhang, Steinmann, Yang, Wang, Wu, Wang, Hao, Bergquist, Utzinger and Zhou2009) or Toxoplasma gondii (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Chen, Li, Zheng, He, Lin and Zhu2011) are of public health and economic importance in Asia, we expect an increased research focus on these parasites and their vectors.

We predict that genomic research on parasites will continue to expand as part of the search for new anti-parasite drugs and vaccines, but parasitological research using Sanger sequencing will not decline as fast as it might for non-parasitic organisms. In contrast to many groups of free-living organisms, much of parasite biodiversity remains to be found and recorded. Accordingly, widely used gene markers (such as the mitochondrial COI or the nuclear 28S rRNA genes) will continue to play key roles in parasite discovery and taxonomy for years to come.

At the same time, the slower adoption of new ideas or technologies in basic parasitological research than in general biology should be remedied. New molecular approaches, such as environmental or eDNA analysis, where DNA (or RNA) is extracted from environmental or organismal matrices, provide promising tools for the study of parasitic organisms (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Stentiford, Littlewood and Hartikainen2015). However, although eDNA surveys have found diverse applications to study free-living organisms (e.g. Thomsen and Willerslev, Reference Thomsen and Willerslev2015; Stat et al., Reference Stat, Huggett, Bernasconi, DiBattista, Berry, Newman, Harvey and Bunce2017; Hering et al., Reference Hering, Borja, Jones, Pont, Boets, Bouchez, Bruce, Drakare, Hänfling, Kahlert, Leese, Meissner, Mergen, Reyjol, Segurado, Vogler and Kelly2018; Lacoursière-Roussel et al., Reference Lacoursière-Roussel, Howland, Normandeau, Grey, Archambault, Deiner, Lodge, Hernandez, Leduc and Bernatchez2018), parasitologists have so far been slow to adopt these methods, with a few exceptions (e.g. Huver et al., Reference Huver, Koprivnikar, Johnson and Whyard2015; Carraro et al., Reference Carraro, Hartikainen, Jokela, Bertuzzo and Rinaldo2018; Rusch et al., Reference Rusch, Hansen, Strand, Markussen, Hytterød and Vrålstad2018). This slow adoption is apparent in other areas, too. For example, although the microbiomes of parasites are now recognised as hugely important for understanding their biology and controlling them (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Brindley, Gasser and Cantacessi2019), a coordinated effort to characterise and analyse parasite microbiomes is only a recent initiative (Dheilly et al., Reference Dheilly, Bolnick, Bordenstein, Brindley, Figuères, Holmes, Martinez, Phillips, Poulin and Rosario2017), appearing years after the establishment of other large-scale, organised programmes such as the Human Microbiome Project, or the Earth Microbiome Project.

One way for the faster incorporation of new developments in the study of parasites would be for the walls isolating different research areas to come down. There exists no society, conference or journal devoted exclusively to the study of non-parasitic organisms. Indeed, conferences and journals of ecology, evolutionary biology, or molecular genetics welcome papers on both parasites and non-parasites. In contrast, there are multiple societies, conferences and journals of parasitology, focused solely on the study of parasites. This one-sided compartmentalisation of the study of life may be responsible for the delayed integration of technologies developed originally for the study of non-parasites, by researchers focused on the study of parasites. The onus is therefore on parasitologists to reach across and fully join the wider biological research community.

Progress will come from the right blend of old and new technologies. However, novel approaches and methods need to infiltrate parasitological research faster than they have for the field to meet its future challenges, from making headway with the discovery of parasite biodiversity to the mitigation of their impact on human health.

Conclusions

(i) Our analysis of publication trends shows that parasite-focused research in the three molecular periods (allozyme, nucleotide, genomics) follows the same overall patterns as the general biological research over the years but at a slightly more conservative rate. Despite the great diversity as well as ecological and medical importance of parasites, the total number of studies on parasitic organisms constitutes less than five percent of the total research output across all molecular periods.

(ii) Medically relevant parasites, in particular protists, dominate parasitology research, making up almost 70% of publications. Across all periods of molecular research, early publications almost exclusively comprise studies on medically relevant parasites and research on non-human parasites only appears in significant numbers after a delay of several years.

(iii) Our analysis reveals a gradual shift in research focus between the three periods, from largely species discovery studies (taxonomy and population genetics) in the allozyme period, to investigating the relationships among various species (phylogeny) during the nucleotide period, and finally addressing broader theory-focused questions (evolution) in the genomics period. Altogether, this suggests an increasing complexity of topics and research questions that can be addressed with the development of more sophisticated molecular tools.

(iv) With the exception of the allozyme period, the research output on molecular parasite research is dominated by authors affiliated with, and presumably financed by, institutions in the United States. Molecular tools are now far more cost-effective and accessible to researchers around the world, and the geographic distribution has begun to shift in recent years as other regions, particularly China, develop their genomic research.

(v) Altogether, we conclude that molecular methods provide powerful tools for research on parasitic organisms, including their diverse roles in ecosystems and their importance as human pathogens. Older methods, such as barcoding approaches using the COI gene, will continue to provide valuable items in the molecular toolbox for parasite research for years to come, since much of parasite biodiversity is still undiscovered. At the same time, we encourage researchers to be on the lookout for, and quickly integrate, novel approaches and methods to advance research on parasitic organisms.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182019000726.

Author ORCIDs

Christian Selbach, 0000-0002-7777-6515; Fátima Jorge, 0000-0002-3138-1729; Alan Eriksson, 0000-0003-1857-7935; Ryan Herbison, 0000-0001-5335-2382; Robert Poulin, 0000-0003-1390-1206.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support from Emerson's Brewing Company. We also thank two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions that improved the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by a research fellowship from the German Research Foundation DFG (C.S., Grant Number: SE 2728/1-1, and SE 2728/2-1), a Marsden Fund awarded to R.P. (F.J., B.P.), University of Otago Doctoral Scholarships (J.F.D., A.F., E.P., B.R.), a University of Otago Summer Research Scholarship (X.C.), a University of Otago Masters Scholarship (R.H.), and financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil (CAPES) (P.M.S., A.E., Grant Number: 88881.187634/2018-01).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.