INTRODUCTION

The free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has been used previously to screen plant cysteine proteinases (CPs) from Carica papaya for nematicidal activity (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). Plant extracts containing active CPs kill parasitic and free-living nematodes in vitro by hydrolysis of the worms’ cuticles. This mode of action is different from that of all commercially available synthetic anthelmintics. Although C. elegans has already been used to screen for compounds or drugs with anthelmintic properties (Simpkin and Coles, Reference Simpkin and Coles1981; Boyd et al. Reference Boyd, McBride, Rice, Snyder and Freedman2010), measurement of efficacy is largely based on assays of motility, effects on lethality and on the number of damaged worms (Katiki et al. Reference Katiki, Ferreira, Zajac, Masler, Lindsay, Chagas and Amarante2011; Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014), most of which are dependent on the observer's subjective interpretation of microscopical images. However, to enable rapid-throughput screening of multiple samples, observer-independent, and preferably automated methods are required. One such recently developed method relies on automated measurement of worm motility (Buckingham and Sattelle, Reference Buckingham and Sattelle2009; Buckingham et al. Reference Buckingham, Partridge and Sattelle2014).

To develop an alternative observer-independent assay for assessment of cuticular damage to C. elegans, we investigated the uptake, retention and release of Neutral red by the worm. Our project was motivated by the precedent of cellular Neutral red retention in coelomocytes derived from earthworms (Lumbricus rubellus) (Weeks and Svendsen, Reference Weeks and Svendsen1996) and pioneering work in Daphnia (Koehring, Reference Koehring1930). Assays based on uptake of Neutral red are widely used with cell lines as measures of cytotoxicity and have been employed with many other applications in the biomedical and environmental sciences (Borenfreund and Puerner, Reference Borenfreund and Puerner1984; Babich and Borenfreund, Reference Babich and Borenfreund1990; Cavanaugh et al. Reference Cavanaugh, Moskwa, Donish, Pera, Richardson and Andrese1990; Repetto and Sanz, Reference Repetto and Sanz1993; Liebsch and Spielmann, Reference Liebsch and Spielmann1995; Repetto et al. Reference Repetto, del Peso and Zurita2008). The success of Neutral red based assays is dependent on the ability of viable cells to incorporate dye by passive diffusion leading to its subsequent binding within the lysosomes. Up to 90% of Neutral red is taken up by lysosomes (Koehring, Reference Koehring1930; Winckler, Reference Winckler1974; Nemes et al. Reference Nemes, Dietz, Luth, Gomba, Hackenthal and Gross1979), and subsequent release of this dye in quantifiable amounts when the cells harbouring the dye are damaged by toxic agents, provides quantitative assessment of damage, hence Neutral red leakage assay (NRLA; Repetto and Sanz, Reference Repetto and Sanz1993; Weeks and Svendsen, Reference Weeks and Svendsen1996; Repetto et al. Reference Repetto, del Peso and Zurita2008).

The availability of bacterially unswollen (bus) C. elegans strains (Gravato-Nobre et al. Reference Gravato-Nobre, Nicholas, Nijland, O'Rourke, Whittington, Yook and Hodgkin2005; Partridge et al. Reference Partridge, Tearle, Gravato-Nobre, Schafer and Hodgkin2008), with their characteristically fragile cuticles, was exploited in this study to explore the cuticular response to CPs of Neutral red-stained worms. The bus phenotype can arise from mutations in several genes affecting the cuticle, bacterial adhesion or colonization, the host swelling response and glycoconjugate biosynthesis (Gravato-Nobre and Hodgkin, Reference Gravato-Nobre and Hodgkin2005; Gravato-Nobre et al. Reference Gravato-Nobre, Nicholas, Nijland, O'Rourke, Whittington, Yook and Hodgkin2005; Partridge et al. Reference Partridge, Tearle, Gravato-Nobre, Schafer and Hodgkin2008; Palaima et al. Reference Palaima, Leymarie, Stroud, Mizanur, Hodgkin, Gravato-Nobre, Costello and Cipollo2010). The reorganization of the epidermis and cuticular layers of these worms results in a more fragile surface as revealed by increased bleach sensitivity, cuticle permeability and multi-drug sensitivity (Partridge et al. Reference Partridge, Tearle, Gravato-Nobre, Schafer and Hodgkin2008). These qualities afford an opportunity for bus strains of C. elegans to be used in drug screening (Partridge et al. Reference Partridge, Tearle, Gravato-Nobre, Schafer and Hodgkin2008; Palaima et al. Reference Palaima, Leymarie, Stroud, Mizanur, Hodgkin, Gravato-Nobre, Costello and Cipollo2010).

It must be noted that all parasitic nematodes tested in vitro, thus far have proved sensitive to plant-derived CPs (Stepek et al. Reference Stepek, Behnke, Buttle and Duce2004, Reference Stepek, Duce, Buttle, Lowe and Behnke2005, Reference Stepek, Lowe, Buttle, Duce and Behnke2007; Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Buttle, Stepek, Lowe and Duce2008; Buttle et al. Reference Buttle, Behnke, Bartley, Elsheikha, Bartley, Garnett, Donnan, Jackson, Lowe and Duce2011; Luoga et al. Reference Luoga, Mansur, Buttle, Duce, Garnett, Lowe and Behnke2015). However, C. elegans is normally relatively resistant through cystatin inhibition of CP action (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). Therefore, using bus or cpi null mutants offers the practical advantage of rendering C. elegans sensitive to CP attack, so that it can act as a surrogate (and much cheaper) model for parasitic species when screening CP-containing plant products for anthelminthic activity.

In order to validate the assay that we report here, intact bus mutant C. elegans worms were stained with Neutral red, and then following exposure to CPs, the stain that leaked into the incubation medium was measured spectrophotometrically to estimate the extent of CP damage to the cuticles and underlying tissues, and concurrent physical damage to the cuticle was assessed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Further evidence in support of the usefulness of the NRLA was provided by assessment of dye release by cystatin null mutants (cpi-1−/− and cpi-2−/−) which, lacking cystatin gene products encoded by the cpi-1 or cpi-2 genes, cannot as readily resist externally applied CPs (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). Since wild-type C. elegans are also highly susceptible to damage by CPs at 0 °C, a temperature at which it has been hypothesized cystatins fail to protect the worms, we also conducted some experiments at both 0 °C and at ambient temperature (a temperature at which wild-type worms are resistant to CPs) (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source and maintenance of worm strains and papaya latex supernatant (PLS)

All strains were maintained on Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) agar plates containing a lawn of 0P50 Escherichia coli at 15 °C as described previously (Guven et al. Reference Guven, Duce and de Pomerai1994). Worms were harvested from agar plates using K medium (53 mm NaCl, 32 mm KCl; Williams and Dusenbery, Reference Williams and Dusenbery1990); Table 1 shows the strain name and genotype of worms employed in this study. All bus strains (Table 1) were provided by Professor Jonathan Hodgkin (University of Oxford, Oxford, UK), and both cystatin null mutants [cpi-1−/− (ok1213) and cpi-2−/− (ok1256)] as well as the wild-type Bristol N2 strain, were supplied by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Centre (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA). All preparations of PLS, containing four CPs (Buttle et al. Reference Buttle, Dando, Coe, Sharp, Shepherd and Barrett1990), were prepared as described previously (Buttle et al. Reference Buttle, Behnke, Bartley, Elsheikha, Bartley, Garnett, Donnan, Jackson, Lowe and Duce2011), and 1 mm L-cysteine was included in all incubations with PLS. Once the preparations were made, aliquoted and frozen, there was no detectable deterioration of the enzyme activity (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). Preparation and active-site titration of micromolar concentrations of CPs was carried out as previously described (Buttle et al. Reference Buttle, Behnke, Bartley, Elsheikha, Bartley, Garnett, Donnan, Jackson, Lowe and Duce2011; Luoga et al. Reference Luoga, Mansur, Buttle, Duce, Garnett, Lowe and Behnke2015), using the CP-specific inhibitor L-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucylamido-(4-guanidino) butane (E-64) (Sigma-Aldrich Ltd., Poole, UK).

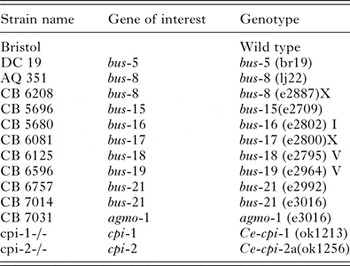

Table 1. Strain names and genotypes of Caenorhabditis elegans used in this study

Neutral red dye

Neutral red (Sigma®, St Louis, USA) stock solution (4 mg mL−1) was prepared by dissolving 40 mg Neutral red dye in 10 mL K medium. The stock solution was kept at ambient temperature protected from light by aluminium foil for up to 2 months until use. To remove any precipitated dye particles from the 4 mg mL−1 stock solution, the stain was filtered through a 0·2 µm Millipore® filter.

Assessment of Neutral red uptake and staining of C. elegans

Worms at different stages of growth were washed off NGM plates with ice-cold K medium and handled as described previously (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). The worm pellets were then transferred into a 50 mL centrifuge tube containing K medium plus a dense bacterial suspension (optical density = 1·0–1·5 at 550 nm) mixed with a 40 µg mL−1 final concentration of Neutral red. The worms and dye were incubated at 20 °C for at least 2 h to allow for consistent staining of the worms, though only a minority of wild-type N2 worms showed any signs of taking up the dye. The suspension was agitated gently using a slow speed on a tube roller during staining. Thereafter, worms were washed three or four times in ice-cold water and centrifuged for 3 min at 1619 × g between washes to remove excess dye.

Assessment of Neutral red retention

Successful uptake and retention of Neutral red was evaluated microscopically. Worm samples of all strains were inspected under an inverted microscope to check for successful and consistent staining. Photographs were taken using a Hiro High Resolution Microscope camera (American Lab and Science, Minnesota, USA) with TSView Digital imaging software.

Treatment of worms and measurement of Neutral red absorbance

Treatments involved 200 µL of stained living worm suspension added to 1000 µL of PLS to give the stated final active CP concentration in 1·5 mL micro-tubes, with or without the addition of E-64 at double the molar concentration of PLS; the concentration of PLS (and E-64), test temperature and duration of exposure were varied, depending upon the aim of the experiment. After treatment, the micro-tubes were shaken and placed on ice for 10–15 min or centrifuged at 11 586 × g for 1 min, to allow worms to settle at the bottom of the tubes. One millilitre of the supernatant was carefully removed from the micro-tube and transferred into a clean plastic cuvette with a 1 cm optical path length. The absorbance of the supernatant was then measured at 540 nm in a spectrophotometer (model-Libra 6, Biochrom, Scientific Laboratory Supplies, Nottingham, UK) that had been zeroed on a K medium blank.

Assessing cuticular damage of Neutral red stained worms using Trypan blue dye

As an independent measure of cell death, samples of the worms treated with CPs as described above and their controls were counterstained with 40 mg L−1 Trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) for microscopy. Controls included unstained worms and worms stained with Neutral red but not treated with CPs. Immediately after Trypan blue staining, worms were placed on a glass slide and cuticular damage was viewed and photographed using a Hiro High Resolution Microscope camera as above.

Effect of PLS on bus and cpi null mutant strains assessed by SEM

The bus strains used were CB 6081, CB 6125, CB 6757, CB 7014, DC 19, CB 5696, CB 7031, AQ 351 and CB 5680 (Table 1), together with N2 controls and both cpi null mutants. Mixed life-stage worms of each strain were prepared from NGM plates and handled separately as described previously. They were left unstained and exposed in duplicate to 45 µ m PLS with or without 100 µ m E-64 for 30 and 60 min. For each strain, an appropriate K medium control was employed. Assays were placed in 24-well plates and incubated at ambient temperature or at 0 °C, because the earlier work had shown that at temperatures above 15 °C wild-type C. elegans resist damage from CPs (it is hypothesized by secretion of cystatins), whereas as 0 °C they are highly susceptible (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). A rapid microscopical assessment of the worms was made at each time point before samples were processed for SEM as described by Phiri et al. (Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014), the latter essentially stopping any further enzyme reaction. Briefly, worms were fixed in 2·5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde for 1 h, and then placed in 0·15 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7·2) for a further hour before the phosphate buffer was changed and worms left overnight at 4 °C. After removal of the phosphate buffer, worms were further fixed in 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide (Agar Scientific Ltd., Stansted, Essex, UK) before being washed three times with distilled water. This was followed by dehydrating the worms for 1 h in ascending concentrations of acetone (30–100%) before drying with a Polaron E3000 critical point drier. All samples were then coated with gold to a thickness of 50 nm using a Polaron sputter-coating unit (Polaron E5100). Worms were examined using a scanning electron microscope (Jeol JSM 840) and images were collected using a digital camera.

Statistical analysis

For the Neutral red assays, optical density measurements (± sem) were analysed in Graphpad Prism 6 by one-way or two-way ANOVA, with Dunnett's or Tukey's post hoc multiple comparisons tests against corresponding K medium controls (no CP). Statistical significance was ascribed at P < 0·05.

RESULTS

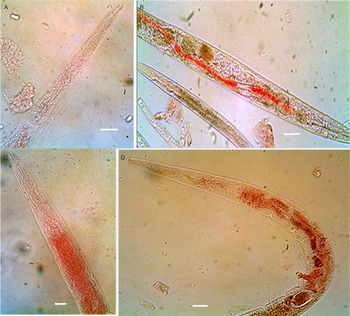

Successful Neutral red uptake and staining in C. elegans

Figure 1 shows a sample of wild-type N2 worms exhibiting successful uptake of Neutral red and consistent staining of the worms at 2 h when feeding bacteria were incorporated, and contrasts this with worms cultured without bacteria, which had minimal staining of the gut, the dye mostly failing to penetrate the cuticle of wild-type N2 worms. All the stained worms were alive prior to CP treatment. In general, only a minority of wild-type N2 worms showed detectable staining with Neutral red, even when abundant food bacteria were present. This may reflect their tough and impermeable cuticle; staining may only be possible when this is weakened, shed and replaced during moulting – a stage through which only some of the larvae present will pass during any given incubation period in the dye.

Fig. 1. Incorporation of OP50 E. coli feeding bacteria in the Neutral red dye enhanced dye uptake. Retention of dye was imaged in N2 wild-type worms after 2 h of incubation at 20 °C in K medium in the presence of 40 µg mL−1 of Neutral red, and was less apparent in the absence (A, B) as compared to the presence (C, D) of feeding bacteria. Scale bars = 63·1 µm.

Caenorhabditis elegans bus strains were highly susceptible to the nematicidal effects of PLS

Caenorhabditis elegans bus strains were exposed to PLS for either 30 or 60 min. In contrast to the wild-type N2 controls, all the bus strains were affected by the CPs within 30 min of exposure at ambient temperature. Cuticular damage was evident in all strains except for N2 (Fig. 2), with previously retained Neutral red escaping through the damaged cuticles of the PLS-treated bus strain worms but not wild-type N2 worms. CP-induced damage was not confined to the cuticle, but started with it. Since the worm interior is under high hydrostatic pressure, once the cuticle was breached, the worms gave way and split outwards from that break. In that event, the worm can be completely destroyed without showing the initial site of cuticular damage. Even though damage was most obvious in the large adult worms, similar damage to much smaller larval worms was also present and much easier to see by SEM. Overall, in quantitative terms, it was easy to count 50 worms in untreated controls, but the number was significantly reduced to single digits in the treated samples as a result of damaged cuticles and disintegration of whole worms.

Fig. 2. Damage by PLS in mixed-stage C. elegans bus mutant strains: worms were stained with Neutral red and exposed to 45 µ m PLS for 30 min at 20 °C. The panels show the control worms alongside the PLS-treated worms. Scale bars: 63·1 µm.

Neutral red leakage is reduced when PLS is blocked with E-64

Neutral red leakage after 1 h at 20 °C was significantly greater for PLS-treated groups than for K medium controls in all of the tested bus strains (P < 0·01 in all cases), but was non-significant in N2 controls (P > 0·05), as shown in Fig. 3. However, Neutral red leakage from bus strains was reduced significantly when PLS was present together with a molar excess of the specific CP inhibitor, E-64 (P < 0·01 for all bus strains). However, in the case of N2 there was no effect (P > 0·05). Although PLS-induced leakage of dye and its blockade by E-64 was clearly seen in all bus genotypes, this was not the case in the wild-type N2, which showed the least response to CP treatment and no reduction when exposed to CP in the presence of E-64.

Fig. 3. Responses of bus strains and wild-type N2 C. elegans to cysteine proteinases: Worms stained with Neutral red were treated with 100 µ m PLS and 100 µ m PLS plus 200 µ m E-64 and incubated at 20 °C for 1 h. Absorbance of Neutral red in the supernatant from exposed worms was measured in a spectrophotometer. The data are expressed as mean and sem derived from three replicates (four for N2 controls). * = P < 0·05, ** = P < 0·01, *** = P < 0·001, or ns = not significant (P > 0·05) (Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

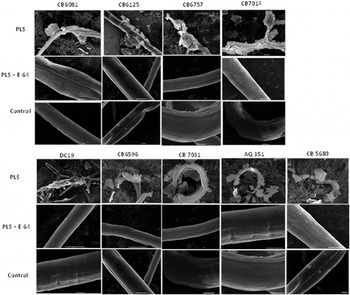

Effect of PLS on bus strains by SEM

All bus strains showed extensive physical damage to their cuticles when exposed to PLS after 30 min at 20 °C (Fig. 4). However, worms incubated in K medium and those exposed to PLS plus E-64 did not show any obvious signs of damage. N2 did not show any damage from PLS alone and no great difference when E-64 was also included (not shown).

Fig. 4. Scanning electron microscopy of bacterially unswollen (bus) strains of C. elegans exposed for 30 min to papaya latex supernatant (PLS): Worms were exposed to 45 µ m PLS and incubated at 20 °C for 30 min. The upper row shows electron micrographs of PLS-treated worms and depicts PLS damage to the cuticle; the middle row shows the blocking effect of incubating PLS with cysteine proteinase inhibitor (E-64), while the lower row shows control worms in K medium only. Scale bars: 10 µm.

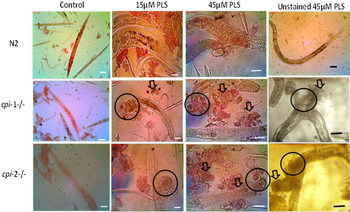

CP-induced cuticular damage highlighted by use of both Neutral red and Trypan blue dyes

Figure 5 confirms extensive CP-induced cuticular damage in cystatin null mutants, and to some extent in wild-type N2 worms, with Neutral red escaping through the damaged cuticle of pre-stained C. elegans (red background) at 20 °C. Although Trypan blue was used to counterstain worms in order to highlight the damage more clearly, the blue stain in the composite images in Fig. 5 is far from obvious, perhaps confirming that these tissues were still viable at the time the worms burst open, and implying that they had not been poisoned as such (through Neutral red or bacterial toxicity) but rather burst open at some point before cell death. Substantial Trypan blue staining of dead cells was not seen in any of the panels shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Assessment of cuticular damage in cystatin mutant worms stained with Neutral red as a result of cysteine proteinase (CP) activity. After 30 min at 20°C, cuticular damage from the action of CPs was evaluated microscopically in worms pre-stained with Neutral red dye. The different rows show wild-type (N2; top), cpi-1−/− (middle) and cpi-2−/− (bottom) strains of C. elegans. In addition, determination of cell death was demonstrated in PLS treated worm samples counter-stained with Trypan blue. All strains were inspected under an inverted microscope. Unstained worm samples are included for comparison. The circles show the part of the worm that was initially damaged and the worms burst or disintegrated from there. The arrows show worm debris after cuticular damage. Scale bars: 63·1 µm.

Time course of NRLA with cystatin null mutant strains

There were no significant effects of PLS (45 µ m PLS and 45 µ m PLS in the presence of 90 µ m E-64) on N2 worms at any time point tested at 20 °C (P > 0·05), whereas both cpi mutant strains showed a significant increase in dye leakage following PLS treatment, even after 1 h (P < 0·05), as shown in Fig. 6. However, there was seemingly no blocking effect of the CP inhibitor E-64 at 1 h and only a small, non-significant inhibition at 3 h (P > 0·05). After 24 h, however, CP treatment of both cpi mutants released large amounts of dye (P < 0·001), and this was largely blocked by E-64 (P < 0·001), whereas no such effect was seen with N2 control worms.

Fig. 6. Time course of Neutral red release from wild-type and cystatin knockout worms exposed to PLS at 20 °C. Cuticular damage as a result of PLS treatment (45 µ m PLS) and the blocking effects of E-64 (45 µ m PLS in the presence of 90 µ m E-64), were evaluated after 1, 3 and 24 h of incubation by measuring the absorbance of Neutral red in supernatants from wild-type N2, cpi-1−/− and cpi-2−/− C. elegans. Bars show the mean and sem derived from 3 replicates (4 in the case of N2). * = P < 0·05, ** = P < 0·001, *** = P < 0·0001, or ns = not significant (P > 0·05) (Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

Effects of PLS on cystatin null mutants at the SEM level

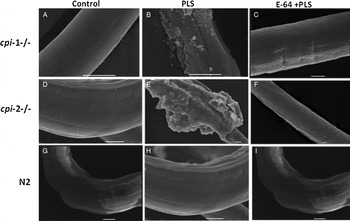

The cuticles of cpi-1−/−, cpi-2−/− and wild-type N2 worms were observed at equivalent points along the body length after exposure to K medium (controls), 45 µm PLS, or 45 µm PLS + 100 µ m E-64. Figure 7 shows scanning electron micrographs of cuticular damage in these null mutants, which is not seen in N2 controls, demonstrating the protective effect of the endogenous cystatins against exogenous CP attack. Null mutant worms treated with PLS exhibited extensive cuticular damage and disruption and digestion of cuticular structure after just 30 min of incubation at ambient temperature, but this effect was largely blocked by E-64.

Fig. 7. Scanning electron micrographs of unstained cystatin null mutants (cpi-1−/− and cpi-2−/−) worms incubated with (45 µm PLS) or without PLS, in the presence (45 µ m PLS + 100 µ m E-64) or absence of excess E-64 at ambient temperature for 30 min. Micrographs were taken as far as possible at equivalent points along the worm's surface near the mid-point. Panels (A–C) show cpi-1−/−, (D–F) show cpi-2−/−, and (G–I) show wild-type N2. The disruption and digestion of the worms’ cuticle by PLS exposed the internal structures (B and E), but this was largely blocked by E-64 (compare C and F). The cuticles of K medium controls (A, D and G) remain intact. Scale bars, 10 µm.

DISCUSSION

All parasitic nematodes tested to-date have proved to be susceptible to digestion by CPs in vitro (Stepek et al. Reference Stepek, Behnke, Buttle and Duce2004, Reference Stepek, Duce, Buttle, Lowe and Behnke2005, Reference Stepek, Lowe, Buttle, Duce and Behnke2007; Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Buttle, Stepek, Lowe and Duce2008; Buttle et al. Reference Buttle, Behnke, Bartley, Elsheikha, Bartley, Garnett, Donnan, Jackson, Lowe and Duce2011; Luoga et al. Reference Luoga, Mansur, Buttle, Duce, Garnett, Lowe and Behnke2015), but screening for novel compounds depends on the provision of live parasitic stages for suitable in vitro assays and therefore entails high costs (e.g. infection and culling of animal hosts) and is extremely labour intensive. Here, a cheap, technically simple and rapid NRLA based on C. elegans has been developed for screening plant CP extracts for anthelmintic activity targeting the cuticular surface of worms, and its suitability for screening purposes has been demonstrated in this study. Although an automated method for assessing worm viability based on motility has been described (Buckingham et al. Reference Buckingham, Partridge and Sattelle2014), our method does not require the use of software and can be carried out using a spectrophotometer as well as a plate reader. Neutral red has been widely applied to mammalian cells in culture (Parish and Müllbacher, Reference Parish and Müllbacher1983; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lipsky, Trump and Hsu1990; Repetto et al. Reference Repetto, del Peso and Zurita2008; Girishkumar et al. Reference Girishkumar, Sreepriya, Praveenkumar, Bali and Jagadeesh2010; Thorne et al. Reference Thorne, Kilford, Payne, Haswell, Dalrymple, Meredith and Dillon2014), and exploited in in vitro cytotoxicity assays based on leakage of the dye from damaged stained cells. Here this approach was successfully adapted for C. elegans and the study of CPs, although at this stage it is not known whether leakage of the dye from damaged worms reflects leakage from cells or through the damaged cuticle from within the worms. This is the first report showing the use of Neutral red as a readily quantifiable way of identifying nematicidal activity of plant products on C. elegans that is independent of investigator bias. It complements previously reported assays that involved counting the number of worms damaged by CPs (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). Using bus strains, this assay provides a cheap, sensitive and simple procedure to run at ambient temperature (rather than at 0 °C as with wild-type worms – see Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). The Neutral red leakage protocol reported here required less equipment than conventional incubation and microscopy-based assessment and about 30 min to run to completion; however, as a result of the leaky structure of their cuticles, some absorbance was also noted in the untreated bus controls. As a quantitative measure of the extent of cuticular damage, the absorbance of leaked Neutral red can be measured on a conventional spectrophotometer at 540 nm; alternatively, this assay can be adapted for use in 96-well plates where the dye concentration in supernatants can be read automatically with a spectrophotometric microplate reader. Additionally, it has been reported that sensitivity could be enhanced by measuring the fluorescence of Neutral red in supernatants with excitation at 530 nm and emission read at 645 nm (Repetto et al. Reference Repetto, del Peso and Zurita2008).

In the development of a suitable protocol for measuring the uptake and leakage of Neutral red, it was important first to find a concentration of the dye that was not toxic to C. elegans, and that was less prone to precipitation yet sufficient to achieve successful uptake and staining. Secondly, standardization of the time needed for adequate staining was required. Thirdly, K medium plus bacterial suspension was incorporated as a medium for dissolving the Neutral red, which in turn enhanced feeding and stain uptake by the worms. The use of this specific staining protocol incorporating feeding bacteria in K medium offered better and more consistent results than using K medium alone. Furthermore, a combination of the staining, exposure to CPs and measurement of Neutral red absorbance in the incubation supernatant was successful when employed with a series of bus strains.

Agents that attack the external layers of a worm are potential anthelmintics (Craig et al. Reference Craig, Isaac and Brooks2007). CPs have been shown to act in this manner, with remarkable success in mammalian hosts (Buttle et al. Reference Buttle, Behnke, Bartley, Elsheikha, Bartley, Garnett, Donnan, Jackson, Lowe and Duce2011; Levecke et al. Reference Levecke, Buttle, Behnke, Duce and Vercruysse2014; Luoga et al. Reference Luoga, Mansur, Buttle, Duce, Garnett, Lowe and Behnke2015) and are capable of killing parasitic nematode worms in vitro as well as in vivo (Stepek et al. Reference Stepek, Duce, Buttle, Lowe and Behnke2005, Reference Stepek, Lowe, Buttle, Duce and Behnke2007; Levecke et al. Reference Levecke, Buttle, Behnke, Duce and Vercruysse2014). However, in contrast to parasitic nematodes, free-living C. elegans worms, across their optimal temperature range (15–25 °C), are known to resist CP attack, at least in part through the action of the secreted cystatins CPI-1 and CPI-2 (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). When the secretion of cystatins is impaired in C. elegans (as in cpi-null mutants), the worms become incapable of mounting effective resistance against CP attack (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). Both of the available cystatin null mutants were far more sensitive to CP attack than wild-type N2 C. elegans. Using the NRLA described herein, the cpi-1−/− mutant in particular was shown to provide an effective rapid-throughput C. elegans-based assay for screening the nematicidal activities of plant-derived CPs. However, the time course for cpi mutants suggests that dye release is slower as compared with bus mutants. The characteristics and severity of cuticular damage are consistent with those reported in parasitic nematodes (Stepek et al. Reference Stepek, Behnke, Buttle and Duce2004, Reference Stepek, Duce, Buttle, Lowe and Behnke2005; Behnke et al. Reference Behnke, Buttle, Stepek, Lowe and Duce2008). While cystatin null mutants have proven to be good models for screening CPs (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014), the quantification of cuticular damage using microscopy had limitations. Adoption of the NRLA with this model ensured that nematicidal effects could be quantified independently of the investigator.

When bus strains that had been exposed to PLS for 30 min at ambient temperature were examined, their susceptibility to CPs was clearly evident through the changes in cuticular integrity that were visualized by SEM. The observed damage seemed even more severe and extensive than that observed in cystatin null mutants (Phiri et al. Reference Phiri, De Pomerai, Buttle and Behnke2014). However, cuticular damage was prevented when worms were incubated with both PLS and the CP inhibitor, E-64. This finding provides strong support for the conclusion that CPs were indeed the cause of the cuticular damage and led to the leakage of the Neutral red and thus increased absorbance. We hypothesize that the mode of action of CPs in this case was facilitated by the fragile cuticle integrity (mechanical and structural) of bus strains, thus allowing easier access by CPs to the underlying structural proteins that they attack. In N2 worms, the cuticle on its own is a formidable barrier that, coupled with cystatins, inhibits CP attack. The presence of active cystatins (CPI-1 and CPI-2) at the surface of the cuticle on their own is unlikely to provide much protection if it is much easier for the CPs to permeate and attack the cuticle from within.

In conclusion, a NRLA has been developed for assessment of damage to the cuticular surface of C. elegans. It involves the pre-staining of worms with Neutral red dye in the presence of bacteria for 2 h, followed by exposure of the stained worms to CPs. Subsequent assessment (through spectrophotometric measurement of absorbance in the supernatant) of the amount of dye released following leakage through the damaged cuticle is then used as a quantitative estimate of cuticular damage. This assay can be carried out at ambient temperature and is independent of any observer-dependent variation. When it incorporates strains with fragile cuticles (bus strains) especially CB 7014, CB 6757 and CB 7031, screening can be completed within 30–60 min after exposure to CPs at concentrations over 15 µ m. The assay requires controls, including untreated worms and those with CP treatment blocked by E-64. Further adaptations to the assay, such as replacement of a conventional spectrophotometer with 96-well plates and a spectrophotometric microplate reader, would increase the speed and number of tests that can be carried out.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Technical assistance and expertise with scanning electron microscopy was provided by Tim Smith in the Advanced Microscopy Unit (School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK).

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

A.M.P. was funded and supported by the Commonwealth Scholarship, University of Nottingham and University of Zambia.