Introduction

Among Haemogregarines, those belonging to the Hepatozoon genus (Miller, 1908) are the most common parasites reported infecting mammals (Wenyon, Reference Wenyon1926; Clark, Reference Clark1958; Desser, Reference Desser1990), birds (Hoare, Reference Hoare1924; Merino et al., Reference Merino, Martínez, Masello, Bedolla and Quillfeldt2014; Valkiūnas et al., Reference Valkiūnas, Mobley and Iezhova2016), amphibians (da Costa et al., Reference da Costa, Pessoa, de Pereira and Colombo1973; Netherlands et al., Reference Netherlands, Cook, Du Preez, Vanhove, Brendonck and Smit2018) and reptiles-like snakes (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Chao and Telford1967; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Desser and Martin1994), lizards (Mackerras, Reference Mackerras1962; Desser, Reference Desser1997) and crocodiles (Carini, Reference Carini1909; Soares et al., Reference Soares, Borghesan, Tavares, Ferreira, Teixeira and Paiva2017); but they are rarely seen in chelonians (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Smit and Davies2009). Haemogregarines are heteroxenous coccidians, their life cycle involves blood-sucking invertebrate vectors (fleas, ticks and mosquitoes, etc.) where sexual development occurs and various vertebrates are intermediate hosts, where the merogonic and gamontogonic cycle take place (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Telford, Reference Telford2008) .

Hepatozoon is a highly diverse group of parasites that has been described in almost all vertebrates around the globe (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Telford, Reference Telford2008) . However, the description and characterization of these organisms are not exempt from difficulties. At the morphological level, descriptions are based on the traits of the gamonts that frequently are the only visible structures in the blood films. Nevertheless, at this stage, only a few morphologic characters are available that are often poorly distinctive (Ball, Reference Ball1967; Telford, Reference Telford2008); Cook et al., Reference Cook, Lawton, Davies and Smit2014; Dvořáková et al., Reference Dvořáková, Kvičerová, Hostovský and Široký2015; Hayes and Smit, Reference Hayes and Smit2019). Also, since for some species, there is little knowledge on the development of the parasite, it may occur that early stages that are rare in blood films might be mistakenly taken as gamonts of different species (Smith, Reference Smith1996). Therefore, for species identification, some authors have recommended that when characterizing the development of the parasites throughout their life cycle, it is good to include morphological characters from other stages different from gamonts (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Chao and Telford1967; Smith, Reference Smith1996; O'Dwyer et al., Reference Valkiūnas2013).

To improve our understanding of the phylogenetic relationships of Adeleorina parasites, genetic information has been included using the 18S rRNA (Barta et al., Reference Barta, Ogedengbe, Martin and Smith2012; Maia et al., Reference Maia, Carranza and Harris2016). This molecular marker has a slow rate of evolution; hence it is widely used for the reconstruction of deep phylogenetic relationships at the higher taxonomic levels such as classes or orders (Hwang and Kim, Reference Hwang and Kim1999). Notwithstanding the above, for this particular case and using this gene, the phylogenetic relationships within the adeleorinid parasites have been mostly clarified (Barta et al., Reference Barta, Ogedengbe, Martin and Smith2012; Karadjian et al., Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015). In fact, the analysis using these sequences have shown that Hepatozoon is a paraphyletic group that includes some species of other genera such as Karyolysus (Karadjian et al., Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2016) and it is closely related to Hemolivia (Kvičerová et al., Reference Kvičerová, Hypša, Dvořáková, Mikulíček, Jandzik, Gardner, Javanbakht, Tiar and Široký2014). This suggests that the scope of the marker for this group could be slightly broader, providing information for the resolution of the genus or even species (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2015; Borges-Nojosa et al., Reference Borges-Nojosa, Borges-Leite, Maia, Zanchi-Silva, da Rocha Braga and Harris2017; Netherlands et al., Reference Netherlands, Cook, Du Preez, Vanhove, Brendonck and Smit2018). In the course of the last decades, the genetic information from the sequences of 18s rRNA has not only allowed the delimitation of some species but has played an important role in genus reassignment for at least two of the parasites described in the Testudines: Haemogregarina parvula, which was assigned to the Hemolivia (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2015) and Heamogregarina fitzsimonsi, which after being placed in the Hepatozoon clade becomes the only species of this genus described as infecting chelonians (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Smit and Davies2009).

During the past decade, many studies have characterized the apicomplexan parasites that infect reptiles of tropical regions of South America (i.e. O'Dwyer et al., Reference O'Dwyer, Moço, dos Santos Paduan, Spenassatto, da Silva and Ribolla2013; Pineda-Catalan et al., Reference Pineda-Catalan, Perkins, Peirce, Engstrand, Garcia-Davila, Pinedo-Vasquez and Aguirre2013; Borges-Nojosa et al., Reference Borges-Nojosa, Borges-Leite, Maia, Zanchi-Silva, da Rocha Braga and Harris2017; Matta et al., Reference Matta, González, Pacheco, Escalante, Moreno, González and Calderón-Espinosa2018; Úngari et al., Reference Úngari, Santos, O'Dwyer, da Silva, de Melo Fava, Paiva, de Pinto and Cury2018; González et al., Reference González, Pacheco, Escalante, Maldonado, Cepeda, Rodríguez-Fandiño, Vargas-Ramírez and Matta2019). Despite this, knowledge about Haemogregarines, particularly in Testudines, is still scarce. Here, we explore the hemoparasites associated with Rhinoclemmys melanosterna, a semi-aquatic turtle inhabiting forested areas in the presence of lentic water bodies (Rueda-Almonacid et al., Reference Rueda-Almonacid, Carr, Mittermeier, Rodríguez-Mahecha, Mast, Vogt, Rhodin, de la Ossa-Velásquez, Rueda and Mittermeier2007). The turtle is distributed from the east coast of Panama, part of the Caribbean coast of Colombia, following the course of the Magdalena River to the Middle Magdalena region and throughout the Pacific coast region to north western Ecuador (Rueda-Almonacid et al., Reference Rueda-Almonacid, Carr, Mittermeier, Rodríguez-Mahecha, Mast, Vogt, Rhodin, de la Ossa-Velásquez, Rueda and Mittermeier2007). Although the species is currently not included in any threat category either globally or in Colombia, the implications of the deep phylogeographic structure revealed for the species by Vargas-Ramirez et al. (Reference Vargas-Ramirez, Carr and Fritz2013), suggest the presence of seven evolutionary significant units (ESU) that should have conservation status.

The goals of this study were (i) to perform the morphological description and molecular characterization of the first hepatozoid species parasitizing a continental turtle in the neotropics; and (ii) to elucidate the phylogenetic relationship with other species of the genus and other adeleorinid coccidias, while discussing the suitability of the use of morphological characters and 18s rRNA sequences for the description of new species. Additionally, we discuss advances in the use of new molecular markers for species identifications of Hepatozoon. This study registered a new host and increases the knowledge about parasitic fauna that infect turtles in Colombia, which has been poorly studied, despite the ecological importance of its charismatic hosts. In this sense, we expect this new information to be useful for the identification of unknown threat factors that should be taken into account in the generation of conservation strategies for Testudines.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and blood film examination

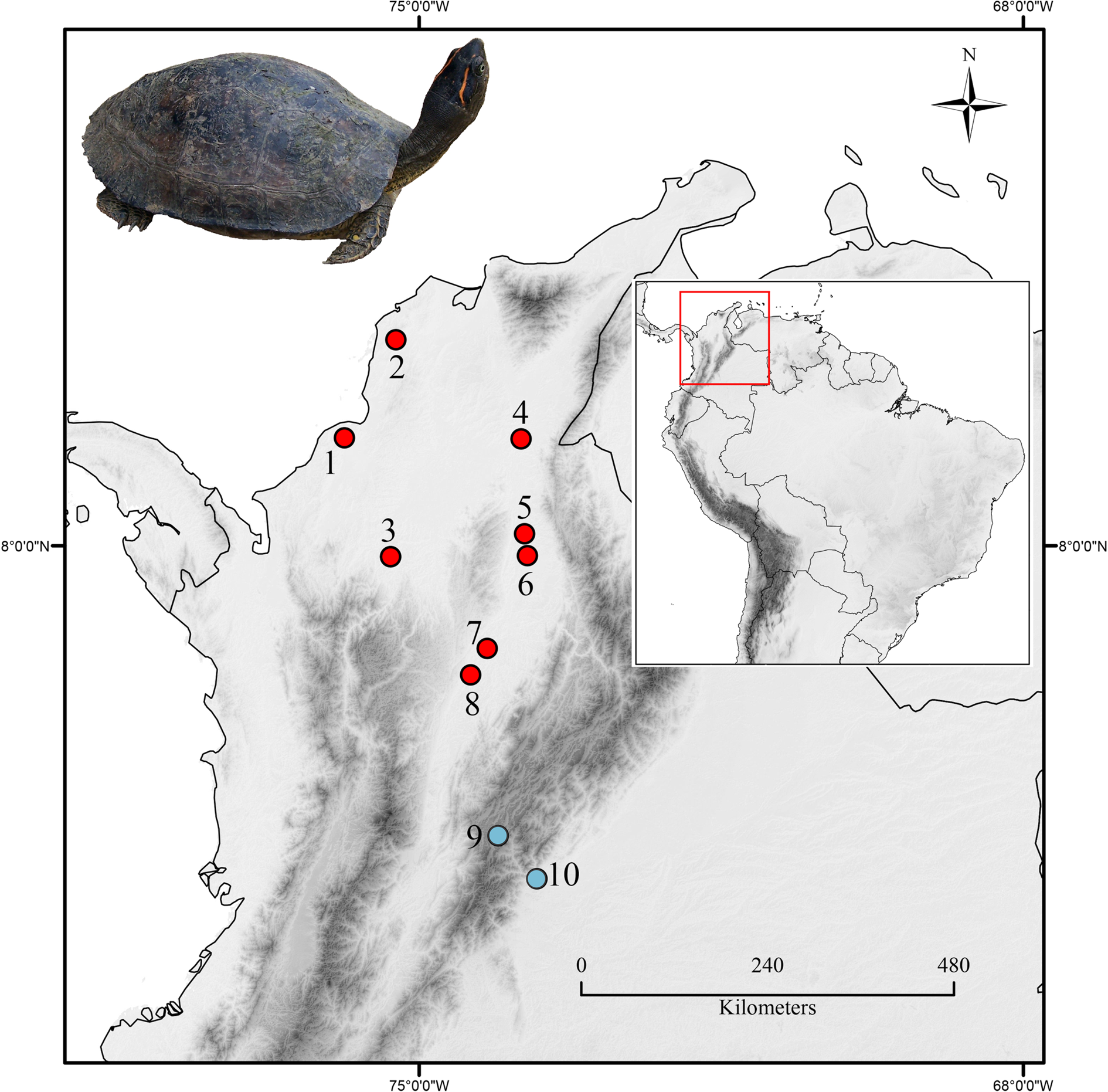

Analysed samples were obtained from individuals captured in the wild, as well as individuals held in captivity in rescue animal centres (Fig. 1, Table 1). Wild turtles were sampled from eight sites in four departments in their natural range of distribution (Fig. 1). At all localities, turtles were found near bodies of water (i.e. swamps, lagoons and marshes) inside of or near forested areas. Forty-six tissue samples from those individuals for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) identification procedures came from the Banco de ADN y Tejidos de la Biodiversidad (BTBC), of the Genetics Institute, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Meanwhile, captive individuals were sampled from two places outside their range of distribution; the animals had been seized from illegal wildlife trafficking. The turtles sampled in the Unidad de Rescate y Rehabilitación de Animales Silvestres (URRAS) in Bogotá at 2600 meters above sea level (m.a.s.l), were kept in plastic pools inside rooms with controlled environmental conditions. The average temperature of the enclosure was 30°C with a 12/12 photoperiod. The turtles from the Estación de Biología Tropical Roberto Franco (EBTRF) in Villavicencio at 459 m.a.s.l., animals were held in artificial ponds, surrounded by vegetation; and the temperature varied from 24 to 26°C, and the relative humidity ranged between 79 and 95%.

Fig. 1. The geographical location of the sampling places. Names and coordinates are provided in Table 1, according to the numbering. Red dots (dark grey in printed version) indicate the places where free-living turtles were captured and sampled and the blue dots (Light grey dots) correspond to rescue animal centres. Inset Photo: Female Rhinoclemmys melanosterna from Arjona, Bolivar.

Table 1. Localities and report of infection of the studied individuals of the Colombian wood turtle Rhinoclemmys melanosterna

N, total number of samples; n mic, number of samples examined by microscopy; *, individual infected with H. simidi sp. nov.

a Localities where the turtles were captured from the wild.

b Animal rescue centres where animals were held in captivity.

From all individuals, about 1 mL of blood was taken from the subcarapacial venous sinus and did not exceed 1% of the body weight. Three thin blood films were made and the remaining blood sample was stored in ethanol 96% for further molecular analyses. The blood films were quickly dried using a fan, fixed with methanol for 5 min and stained with Giemsa at 4% as proposed by Rodríguez and Matta (Reference Rodríguez and Matta2001).

The blood films obtained from the individuals sampled in Yondó (Antioquia) and URRAS (Bogotá) were analysed using an Olympus CX41 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification of 100 × and photographs were taken using the Olympus DP27 integrated camera and the CellSens software (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The Haemogregarines were identified to genus using morphological and morphometric characteristics (Telford, Reference Telford2008); Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2015; Javanbakht et al., Reference Javanbakht, Široký, Mikulíček and Sharifi2015). Parasitaemia was established by the relationship between the number of infected erythrocytes in a total of 10 000 screened erythrocytes. This resulted from the close observation of 100 optical fields at 1000 magnification.

DNA extraction and 18s rRNA amplification

DNA was extracted from blood samples preserved in absolute ethanol using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue extraction kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). 18S rRNA gene amplification was performed using the primers set HepF300/HepR900 (Ujvari et al., Reference Ujvari, Madsen and Olsson2004) to obtain a fragment of approximately 600 base pairs (bp). The original protocol was modified by adding five cycles with an annealing temperature of 50°C for 45 s prior to the 35 cycles of amplification that were indicated. The PCR products were visualized in a 1.5% agarose gel, cleaned using differential precipitation with ammonium acetate protocol (Bensch et al., Reference Bensch, Stjernman, Hasselquist, Örjan, Hannson, Westerdahl and Pinheiro2000) and sequenced in both directions using a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Phylogenetic analysis

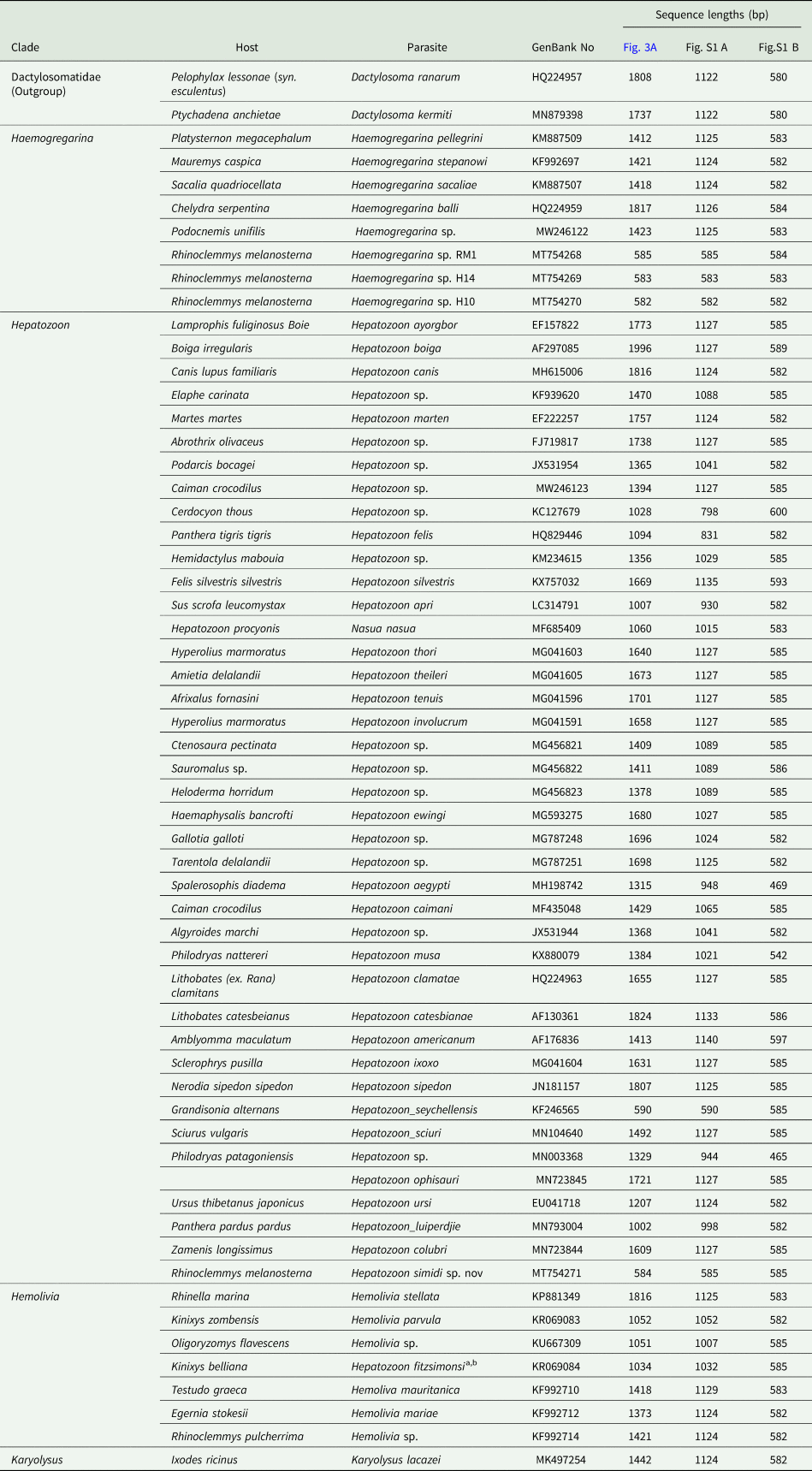

Three alignments using sequences of different lengths were generated to estimate the phylogenetic relationships of the new Hepatozoon species described here, as well as the lineages of Haemogregarina sp. reported in this study. All databases included 59 sequences of 18s rRNA of Hepatozoon (43 lineages), Hemolivia sp. (5), Karyolysus sp. (1), Haemogregarina sp. (8, including lineages here reported) and Dactylosoma sp. (2, used as outgroup). In the first alignment, full-size sequences up to 1800 bp were analysed while in the second and third databases, lineages of 1000 and 585 bp, respectively, were used (Table 2). Such alignments were constructed in MEGA 7 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016) and were aligned with MAFFT (Katoh et al., Reference Katoh, Misawa, Kuma and Miyata2002), available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/mafft/.

Table 2. Morphometric measurements of gamonts and host cells of Hepatozoon simidi sp. nov. Measurements of H. fitzsimonsi, H. colubri and H. rarefaciens are provided for comparison

Measurements are given in μm or μm2. Minimum and maximum values and mean ± s.d. are provided.

a According to Cook et al. (Reference Cook, Smit and Davies2009).

b According to Börner (Reference Börner1901).

c According to Han et al. (Reference Han, Wu, Dong, Zhu, Li, Zhao, Wu, Pei, Wang and Huang2015).

d According to Ball et al. (Reference Ball, Chao and Telford1967).

The phylogenetic reconstructions were estimated using both Bayesian inference (BI) as well as Maximum Likelihood (ML). The BI analyses were carried out using MrBayes version 3.1.2 (Ronquist et al., Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, Van Der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012), and implemented in the platform CIPRES Science Gateway V 3.3 (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2010). These analyses were performed under the general time-reversal model (GTR + I + G) suggested by jModelTest 2.1.1 (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Taboada, Doallo and Posada2012) as the best of 88 models according to the corrected information criterion of Akaike (AIC). For BI two independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations were run simultaneously; using 5 × 106 generations sampled every 500 generations. Convergence was reached when the average standard deviation of the posterior probability was less than 0.01 and was also assessed using the software Tracer v1.6 (Rambaut et al., Reference Rambaut, Suchard, Xie and Drummond2013). After discarding 25% of the trees as burn-in, 37 500 trees were used to build the majority rule consensus tree, which was visualized and edited using FigTree version 1.3.1 (Rambaut and Drummond, Reference Rambaut and Drummond2010).

The ML analyses were performed using the software PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., Reference Guindon, Delsuc, Dufayard, Gascuel and Posada2009) using the same model mentioned above, leaving the ‘estimated’ option for the proportion of invariable sites and the gamma shape parameter. In this phylogenetic analysis nodal supports were calculated using 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Genetic distances between taxa were calculated for both alignments, whereas between and within genera were estimated only for the first alignment using the Kimura two-parameter substitution model implemented in the software MEGA 7 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher and Tamura2016).

Results

Sample collection and blood film examination

Samples of 70 turtles R. melanosterna were screened for blood parasites. Although PCR tested all individuals, only 24 had a blood smear available for microscopic analysis. The other 46 samples came from the BTBC, which has a different purpose and does not collect blood films (Fig. 1, Table 1). Eight samples were positive (overall prevalence: 11.42%) four of them were screened by microscopy, but all the samples were positive by PCR. Seven infected with Haemogregarina sp. (prevalence: 10%) and one that corresponds to a single infection of the new Hepatozoon species (prevalence: 1.42%).

Taxonomic summary

Suborder: Adeleorina Léger, 1911

Family: Hepatozoidae Wenyon, 1926

Genus: Hepatozoon Miller, 1908

Hepatozoon (simidi sp. nov

Type host: Rhinoclemmys melanosterna Gray, 1861 (Geoemydidae) Colombian wood turtle.

Type locality: free-living environment in ‘El Silencio’ natural reserve (6.8057N, −74.206W), Middle Magdalena river valley rain forest, municipality of Yondó, Antioquia, Colombia.

Type material: Hapantotype, three blood smears from R. melanosterna were deposited at the biological collection ‘Grupo de Estudio Relación Parásito Hospedero’ (GERPH), at the Department of Biology, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

Site of infection: mature erythrocytes

Prevalence: One individual was positive (1.42%) for Hepatozoon simidi sp. nov.

Parasitemia: the parasitemia for Hepatozoon simidi sp. nov, was 0.68%.

Distribution: This species was found only in the type locality.

Vector: Unknown.

DNA sequences: the 18S rRNA lineage RM4 (585 bp) obtained from type host R melanosterna was deposited in GenBank under accession N°MT754271.

Etymology: The species name refers to the word ‘simidi’, which is used by the ‘Embera’ native group to name ‘turtle.’ These native people live in a part of the geographical area of Colombia, where R. melanosterna is found.

Description of blood stages

The morphology found reflects different stages of development of the parasite. Immature gamonts (Fig. 2A–H) are cylindrical with a straight central axis and rounded ends, or slightly curved ‘bean-like’ (Fig. 2E–H). Interestingly, it should be noted that 100% of the gamonts cause the host cell nucleus to be pushed aside. A capsule may surround the parasite (Fig. 2B, E, H); the pale-blue cytoplasm has a granular appearance and sometimes possesses fine vacuoles and granules of different sizes (Fig. 2C, D, G, H). A round vacuole is often seen at one end of the parasite (Fig. 2A and D). Uncondensed chromatin is observed at the central (Fig. 2A) or subcentral position (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Hepatozoon simidi sp. nov. (A–L) and Haemogregarina sp. (M–P) found in the Colombian Wood Turtle (Rhinoclemmys melanosterna). Young gamonts (A–H), and mature gamonts (I–L) of Hepatozoon simidi sp. nov. from the bloodstream of the type host. Black arrows indicate the parasite nucleus, whereas the white arrows show the vacuole-like patches at the tip of parasite structures. Black arrowheads indicate the granules and white arrowheads, the tiny vacuoles in the cytoplasm. Asterisks are located over the host cell nucleus. Giemsa-stained blood films. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Mature gamonts, this stage shows larger parasites (Fig. 2I–L; Table 2), which causes a great deformation of infected cells. The chromatin is condensed, and the nucleus of RBC is displaced from a central position to a lateral position (Fig. 2J) or polar position (Fig. 2L) or even expelled from the host cell (Fig. 2I). The parasite shows an intense blue-stained cytoplasm, irregular in appearance. Multiple pigment granules with variable affinities for the dye from pink to purple (Fig. 2J and L) are mainly distributed around the parasite nucleus (Fig. 2K) but can also be found dispersed throughout the entire body of the gamont (Fig. 2I and L). In at least 70% of the mature parasites, clear space between the parasite and RBC's cytoplasm is observed; it could be a capsule or parasitophorous vacuole (Fig. 2K, L).

Remarks

To date, Hepatozoon fitzsimonsi is the only parasite that has been found parasitizing chelonian hosts (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Smit and Davies2009). The species described here is the second Hepatozoon species reported in a cryptodiran turtle species and the first species reported in a freshwater turtle species of the family Geoemydidae. Despite the phylogenetic proximity with H. fitzsimonsi hosts, gamonts of H. simidi sp. nov are similar to Hepatozoon rarefaciens, a parasite that has been found infecting colubrid snakes in Canada. However, H. rarefaciens gamonts are slightly shorter and slender than H. simidi sp. nov (Table 3). Unfortunately, there are no genetic lineages from H. rarefaciens available for comparison.

Table 3. 18S rRNA sequences aligned to construct the phylogenetic hypothesis. Sequence length used in each phylogenetic hypothesis of Fig. 3 and Fig. S1 are provided

Hepatozoon simidi sp. nov can distinguish from H. fitzsimonsi and other Hepatozoon species by combining their morphological features with the nuclear molecular marker's information. For this species, it is noteworthy that the mature gamonts' width is almost twice the width of most of the genus species already described; and gamonts possessed equally wide ends that give a characteristic appearance of a slightly curved cylinder (Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis

Using sequences with different lengths, three phylogenetic hypotheses were generated and different rearrangements of clades and taxa were observed. Overall, both tree-building methods for phylogenetic reconstruction showed almost the same topology. Hepatozoon parasites appear into four different clades (Fig. 3, clades A–E), and Karyolysus was included in one of them (Fig. 3, clade E). In the phylogenetic reconstruction using full-length sequences (Fig. 3A), Haemogregarina (clade II) parasites diverge from a clade that includes Hepatozoon, Karyolysus and Hemolivia, depicted in clade I. In such clade I, Hemolivia lies basal to Hepatozoon clades from amphibia (Fig. 3, clade A) and reptile (clades B and C).

Fig. 3. Phylogenetic hypothesis obtained using Bayesian inference and maximum likelihood constructed from 18S rRNA sequences of 1800 bp. The lineages obtained in this study are highlighted in bold font. Branches colour indicates the parasite genus as follows: green (light grey in printed version) for Hepatozoon sp., blue (medium grey) for Hemolivia sp., purple (white) for Karyolysus sp., red (black) for Haemogregarina and grey (Dark grey) for the outgroup (Dactylosoma sp.). The silhouettes located near the clade nodes indicate the host from which the parasites were isolated: a frog for amphibians, a lizard for reptiles, a turtle for turtles and tortoises, and a bear for mammals. Bootstrap values and posterior probabilities are shown above the nodes. Nodal supports below 80/0.8 are not shown. The branch lengths are proportional to the amount of change. Scale bar indicating substitutions per site is provided.

Hepatozoon simidi sp. nov. was located in a small clade (Fig. 3, clade C) along with H. colubri in all hypotheses performed (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1) with a low nodal support. This small clade was placed in a polytomy that included lineages from other reptiles, and the clade of amphibian Hepatozoon (Fig. 3, clades A and B), whose genetic divergences ranged between 0.03 (clade B vs clade C) and 0.05 (clade A vs clade C- Table S1). Furthermore, the new Hepatozoon species was separated by its sister taxa H. colubri by a genetic distance of 0.019; and from the second most closely related H. fitzsimonsi by a divergence of 0.03 (Table 4).

Table 4. Genetic distance calculated using K2P model of substitutions, between 18SrRNA lineages of Adeleorina parasites for the three different alignments in Fig. 3 and Fig. S1

Haemogregarina lineages amplified in this study were placed basal of two distinct clades including parasite species reported infecting old-world Testudines (Fig. 3 clades G, H and I). The genetic distance between neotropical and old-world parasites of this genus ranged between 0.49 (clade G vs clade H) and 0.082 using 585 bp sequences (Fig. S1 B, clade G vs clade I), or 0.076 using sequences of 1000 bp (Fig. S1 A, clade G vs clade I; Table S1). Indeed, divergences within Haemogregarina parasites may reach values of 0.096 when comparing lineage (MT754270 with Haemogregarina sacaliae, Table 4, Fig. 3 and Fig. S1).

Discussion

Sample collection and blood film examination

This is the first report of an Hepatozoon parasite infecting a neotropical continental turtle, R. melanosterna, distributed in northwestern South America. In the Neotropics other species of Rhinoclemmys have been previously reported infected with Hemoregarines: in Costa Rica, the black river turtle (Rhinoclemmys funerea) was found infected with Haemogregarina sp. and probably Hepatozoon sp., (Rossow et al., Reference Rossow, Hernandez, Sumner, Altman, Crider, Gammage, Segal and Yabsley2013) and in Nicaragua, the Central American wood turtle (Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima) infected with Hemolivia sp. (Kvičerová et al., Reference Kvičerová, Hypša, Dvořáková, Mikulíček, Jandzik, Gardner, Javanbakht, Tiar and Široký2014). Genetic distances with the latest were for H. simidi sp. nov. of 0.04 (Table 4), which is between Haemogregarina sp. RM1 and Hemolivia sp. from R. pulcherrima; while for Haemogregarina lineages H10 and H14 were 0.09 and 0.05, respectively (Table 4).

At the genetic level, the closest taxon to H. simidi is H. colubri (Börner, Reference Börner1901), a parasite isolated from Zamenis longissimus (Zechmeisterová, unpublished results) and other Colubridae (Pessoa, Reference Pessoa1967), and also from Phytonidae (Börner, Reference Börner1901). The next closest is H. fitzsimonsi. There are few morphological details on H. colubri; however, according to the original description, the parasites seem to be shorter and slender than H. simidi sp. nov. (Table 4).

Hepatozoon parasites can be transmitted by many blood-sucking arthropods. To the successful transmission of a heteroxenous parasite, there should be a spatiotemporal coincidence of the parasite, the host and the vector (Eldridge, Reference Eldridge, Eldridge and Edman2004). Besides, some heteroxenous parasites may be transmitted horizontally or even vertically by facultative vias without the participation of true vectors (Kauffman et al., Reference Kauffman, Sparkman, Bronikowski and Palacios2017). Rhinoclemmys melanosterna is a semi-aquatic turtle that prefers swampy environments and is rarely found far away from such water bodies, so the habitat preference shown by this turtle may make transmission difficult if the vectors are ticks [as it is supposed for H. fitzsimonsi; (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Smit and Davies2009)], or blood-sucking dipterans (Smith, Reference Smith1996). An alternative pathway for the transmission of Hepatozoon in reptiles is the ingestion of infective stages through predation (Ball, Reference Ball1967; Landau et al., Reference Landau, Michel, Chabaud and Brygoo1972). Although R. melanosterna is mainly herbivorous, occasionally eats small fishes, frogs or tadpoles (Rueda-Almonacid et al., Reference Rueda-Almonacid, Carr, Mittermeier, Rodríguez-Mahecha, Mast, Vogt, Rhodin, de la Ossa-Velásquez, Rueda and Mittermeier2007); thereby the infection by ingestion of an infected animal, as well as the possibility of this host species being an intermediate in a more complex life cycle, cannot be ruled out.

To date, only H. fitzsimonsi has been described in a Testudine host using molecular and morphological data. Although there are few distinctive characters in the gamonts that can be used in the description of the Hepatozoon species (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Chao and Telford1967), such parasite structures of H. simidi sp. nov. found in R. melanosterna were compared to those present in H. fitzsimonsi, revealing many distinctive features that the species in this description possesses. This parasite is even larger than others belonging to the Haemogregarine's group (Table 3, Fig. 2), that cause marked hypertrophy of the host cell from early stages. Also, the presence of large granules dispersed throughout the parasite is distinctive. The nature of these granules is still unknown; however, similar granules have been reported in haemosporidians as volutine granules (Valkiūnas, Reference Valkiūnas2005; Lotta et al., Reference Lotta, Valkiūnas, Pacheco, Escalante, Hernández and Matta2019). Electronic micrography studies are desirable for characterizing the morphological features, as well as to define more microscopic details that eventually can be used as diagnostic morphological characters.

Phylogenetic analysis

In agreement with previous studies, our phylogenetic reconstructions revealed Karyolysus lineages within Hepatozoon, making it a paraphyletic genus (Barta et al., Reference Barta, Ogedengbe, Martin and Smith2012; Karadjian et al., Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2016). Furthermore, H. simidi sp. nov. was consistently placed as part of a polytomy, including some other reptile and anuran parasite species, with low nodal support, most probably due to the size of the sequence analysed.

Using sequences of 18S rRNA, several authors have proposed that an interspecific genetic distance of above 1% could be enough to differentiate species, bearing in mind the low evolutionary rate mentioned (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2015; Borges-Nojosa et al., Reference Borges-Nojosa, Borges-Leite, Maia, Zanchi-Silva, da Rocha Braga and Harris2017; Netherlands et al., Reference Netherlands, Cook, Du Preez, Vanhove, Brendonck and Smit2018). Based on the large genetic distance found between the lineage MT754271 (H. simidi sp. nov.) with the closest lineages belonging to the genus Hepatozoon isolated from reptiles (2% with H. colubri and 3% with H. fitzsimonsi from the tortoise Kinixys belliana), we might conclude that this parasite lineage represents an undescribed parasite species.

It is important to mention that the lineage of H. simidi sp. nov. fall in the clade identified as Bartazoon genus proposed by Karadjian et al. (Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015). However, the Bartazoon genus has specific features in the sporogonic development in the invertebrate vector, described widely in Karadjian et al. (Reference Karadjian, Chavatte and Landau2015). Unfortunately, we have no information about sporogonic development or even a possible vector that allows us to give bases to designate this new species to the Bartazoon genus.

As for Haemogregarina parasites, high genetic distances found between the different lineages analysed, either from the old world and neotropical hosts, might be revealing a high diversity within this parasite genus that remains to unveil. In turn, it can also be indicative of the low number of taxa of this genus used to build the phylogenetic hypothesis.

Here we described a new parasite species belonging to the genus Hepatozoon. The description of H. simidi sp. nov. was based on both morphological and molecular approaches, and this is the first report of Adeleorinid hemoparasite infections in R. melanosterna from Colombia. To a more accurate description of new parasite species belonging to this group, it would be ideal to have information about the vector's development stages and tissue stages in the vertebrate (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Chao and Telford1967; Smith, Reference Smith1996). Besides, new molecular markers would improve phylogenetic relationships. The mitochondrial genome has been seen as a good candidate given the evolution rate of the genes encoded there (Escalante et al., Reference Escalante, Freeland, Collins and Lal1998; Pacheco et al., Reference Pacheco, Matta, Valkiūnas, Parker, Mello, Stanley, Lentino, Garcia-Amado, Cranfield and Kosakovsky Pond2017) as well as their widespread use in other apicomplexa groups of parasites (Bensch et al., Reference Bensch, Stjernman, Hasselquist, Örjan, Hannson, Westerdahl and Pinheiro2000; Martinsen et al., Reference Martinsen, Perkins and Schall2008; Perkins, Reference Perkins2008; Ogedengbe et al., Reference Ogedengbe, Hanner and Barta2011; Witsenburg et al., Reference Witsenburg, Salamin and Christe2012; Borner et al., Reference Borner, Pick, Thiede, Kolawole, Kingsley, Schulze, Cottontail, Wellinghausen, Schmidt-Chanasit and Bruchhaus2016; González et al., Reference González, Pacheco, Escalante, Maldonado, Cepeda, Rodríguez-Fandiño, Vargas-Ramírez and Matta2019 among others). In this regard, recent advances have been achieved for the mitochondrial genome sequencing of Hepatozoon catesbianae and Hepatozoon griseisciuri (Léveillé et al., Reference Léveillé, Ogedengbe, Hafeez, Tu and Barta2014, Reference Léveillé, El Skhawy and Barta2020), from which high genetic divergences have been found within the nominal taxa.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182021000184.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professors Favio González and Luis Fernando García of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for their advice and assistance with this research project. A special acknowledgment goes to Paola González, friend and a member of the GERPH research group for her kind help during the development of the manuscript. Also, thanks to the staff of the reserve ‘El Silencio’ of the Biodiversa Foundation in Yondó, Antioquia, to the professor Carlos Moreno leader of the ‘Unidad de Rescate y Rehabilitación de Animales Silvestres’ (URRAS) in Bogotá, and the ‘Estación de Biología Tropical Roberto Franco’ (EBTRF) in Villavicencio for their collaboration during the field work.

Financial support

This study was supported by the ‘Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación’ MINCIENCIAS (Project code 1101-776-57872) and the ‘Dirección de Investigación’ of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Specimens were collected under the collection permit 255 of 2014 issued by the National Environmental Licenses Authority (ANLA) to the Universidad Nacional de Colombia by resolution. All specimens captured were released after the blood sample collection. Sampling methods were approved by the ‘Institutional Bioethics committee of the Fundación Universitaria-Unitrópico’ on May 22 of 2017 and the Bioethics Committee of the science Faculty of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, by act 03-2019.