Introduction

Accidental hosts of the metastrongyloid nematode Angiostrongylus cantonensis (the rat lungworm) include man, dog, horse and various wildlife species (Cowie, Reference Cowie2013; Barratt et al., Reference Barratt, Chan, Sandaradura, Malik, Spielman, Lee, Marriott, Harkness, Ellis and Stark2016). In these hosts, infection is acquired after ingesting third-stage larvae (L3) encysted within intermediate hosts (various molluscs) or paratenic hosts (frogs, toads, monitor lizards, planarians, freshwater prawns, centipedes and land crabs) (Barratt et al., Reference Barratt, Chan, Sandaradura, Malik, Spielman, Lee, Marriott, Harkness, Ellis and Stark2016). After ingestion, L3 penetrate the walls of the stomach and small intestine, travel via the portal circulation to the liver, then to the right side of the heart, lungs and the left ventricle (Mackerras and Sandars, Reference Mackerras and Sandars1955). Subsequent haematogenous spread results in localization to the central nervous system (CNS) where mechanical damage and inflammation cause clinical disease, referred to as neuroangiostrongyliasis (NA) or rat lungworm disease (Lunn et al., Reference Lunn, Lee, Smaller, Mackay, King, Hunt, Martin, Krockenberger, Spielman and Malik2012). Some researchers have speculated that the migration pathway to the spinal cord may involve peripheral nerves (Prociv and Turner, Reference Prociv and Turner2018) to explain preferential involvement of the cauda equina in some species, such as the dog (Jindrak and Alicata, Reference Jindrak and Alicata1970; Mason, Reference Mason1987).

The nervous system provides an environment which favours the growth and development of L3 as they migrate cranially (Mackerras and Sandars, Reference Mackerras and Sandars1955). In accidental hosts, third- and fourth-stage larvae generally remain in the CNS until they eventually die. Their movement, excretory products, shed cuticle (after moulting) and eventual death triggers eosinophilic meningitis and sometimes encephalitis, myeloradiculitis and/or peripheral radiculoneuritis (Lunn et al., Reference Lunn, Lee, Smaller, Mackay, King, Hunt, Martin, Krockenberger, Spielman and Malik2012; Barratt et al., Reference Barratt, Chan, Sandaradura, Malik, Spielman, Lee, Marriott, Harkness, Ellis and Stark2016). In some human patients (Prociv and Turner, Reference Prociv and Turner2018) and macrobats (Mackie et al., Reference Mackie, Lacasse and Spratt2013), worms may mature and reach the pulmonary arteries. Ocular disease can occur if larvae reach the eye (Barratt et al., Reference Barratt, Chan, Sandaradura, Malik, Spielman, Lee, Marriott, Harkness, Ellis and Stark2016). The most common clinical features of human NA include headache, nuchal rigidity, paraesthesiae (usually of the extremities), vomiting and nausea (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lai, Zhu, Chen and Lun2008). In dogs, however, signs of ascending motor paresis to paralysis, spinal and tail base hyperaesthesia and urinary incontinence predominate (Mason, Reference Mason1987; Lunn et al., Reference Lunn, Lee, Smaller, Mackay, King, Hunt, Martin, Krockenberger, Spielman and Malik2012).

In human NA, changes observed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spinal cord are diverse, non-specific and dynamic. Focal to widespread areas of T2-weighted (T2W) and T2W fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity are often seen in the white matter of the brain, as well as enhancement of the leptomeninges on post-gadolinium T1-weighted (T1W) sequences (Kanpittaya et al., Reference Kanpittaya, Jitpimolmard, Tiamkao and Mairiang2000; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Ma, Ma, He, Ji and Yin2008; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Tseng, Yen, Chen, Sy, Lee, Wann and Chen2012). Characteristic nodular, linear or hockey-stick-shaped lesions that are T2 hyperintense, T1 hypointense and contrast-enhancing are sometimes seen, which likely represent worm tracks and microhaemorrhagic lesions due to larval migration through the CNS (Kanpittaya et al., Reference Kanpittaya, Jitpimolmard, Tiamkao and Mairiang2000; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Ma, Ma, He, Ji and Yin2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kuo, Lo, Huang, Wang and Wang2014). These signs of larva migrans may be more readily seen with T2*-weighted (T2*W) gradient echo (GRE) and susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) sequences which allow for more sensitive detection of blood degradation products (Kanpittaya et al., Reference Kanpittaya, Jitpimolmard, Tiamkao and Mairiang2000; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kuo, Lo, Huang, Wang and Wang2014; Ansdell and Wattanagoon, Reference Ansdell and Wattanagoon2018). In humans, use of high tesla (T) scanners and cutting-edge technology such as three-dimensional (3D) MRI may provide the opportunity for earlier diagnosis, as more subtle lesions can be appreciated (Ansdell and Wattanagoon, Reference Ansdell and Wattanagoon2018). In human cases with radicular syndromes, such as migratory neuropathic pain, focused MRI of the spine can detect a patchy increased signal intensity in the anterior (ventral) or central grey matter (Ansdell and Wattanagoon, Reference Ansdell and Wattanagoon2018; Busse et al., Reference Busse, Gottlieb, Ferreras, Bain and Schechter2018; McAuliffe et al., Reference McAuliffe, Fortin Ensign, Volk, Quast, Narita, Cathey, Larson, McAuliffe, Mukaigawara, Yetto, Ohkusu and Bavaro2018), and axial T1W post-contrast imaging of the cauda equina can show diffuse abnormal nerve root enhancement (McAuliffe et al., Reference McAuliffe, Fortin Ensign, Volk, Quast, Narita, Cathey, Larson, McAuliffe, Mukaigawara, Yetto, Ohkusu and Bavaro2018). Although the use of imaging is not essential to make a definitive diagnosis of NA, MRI assessment of the extent and severity of brain and spinal cord involvement facilitates the determination of disease severity, thereby informing on the overall clinical course and prognosis (McAuliffe et al., Reference McAuliffe, Fortin Ensign, Volk, Quast, Narita, Cathey, Larson, McAuliffe, Mukaigawara, Yetto, Ohkusu and Bavaro2018).

MRI findings in dogs with NA have not been reported to date. Thus, the contribution of such imaging studies in relation to both the pathophysiology of canine NA and its differential diagnosis is currently unknown. This case series aims to amend this knowledge gap by providing preliminary MRI observations in a representative cohort of 11 dogs with NA.

Methods

MRI sequences were obtained from dogs with presumptively or definitively diagnosed NA that had undergone an MRI examination as part of their diagnostic work-up. Patients were investigated in several multi-disciplinary veterinary referral hospitals around Australia. A presumptive diagnosis of NA was made based on characteristic clinical signs (hind-limb paresis and/or proprioceptive ataxia, tail paresis, spinal and tail base hyperaesthesia, and urinary incontinence), eosinophilic pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and an appropriate response to therapy (prednisolone ± fenbendazole). A definitive diagnosis was made based on positive CSF serology [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody testing at the Parasitology Unit, Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research, Westmead Hospital] and/or real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) testing (Veterinary Pathology Diagnostics Service, Sydney School of Veterinary Science) using a novel, highly sensitive, bioinformatically-informed repetitive target developed at the Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD, USA (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Pai, Churcher, Davies, Braddock, Linton, Yu, Bell, Wimpole, Dengate, Collins, Brown, Reppas, Jaensch, Wun, Martin, Slapeta and Malik2020).

Depending on the referral hospital, MR images of the spinal cord and/or brain were obtained using either high-field 1.5 T (Siemens MAGNETOM Essenza®) or low-field 0.25 T (Esaote Vet-MR GRANDE®) machines. MRI protocols were selected by the case radiologist and included various combinations of the following: transverse, sagittal, dorsal and 3D T1W; transverse, sagittal and dorsal T2W; transverse T2W FLAIR and T2*W GRE; dorsal T2W short tau inversion recovery (STIR); and post-gadolinium transverse, sagittal, dorsal and 3D T1W and transverse T2W FLAIR sequences.

Eleven dogs meeting the inclusion criteria were found; 4 from Small Animal Specialist Hospital (North Ryde), 3 from the University Veterinary Teaching Hospital Sydney (Camperdown) and 1 each from Sydney Veterinary Emergency & Specialists (Rosebery), North Shore Veterinary Specialist and Emergency Centre (Artarmon), and James Cook University Veterinary Hospital (Townsville). Our tabulated findings are based on the specialist radiology reports and case histories that were retrievable (cases 1–6 & 8–11), and case notes on the CSF analysis laboratory submission sheet in the remaining patient (case 7). In 7 cases the diagnosis of NA was definitive, based on positive CSF serology (cases 1, 3, 5 and 7) and/or qPCR testing (cases 2, 6 and 9), while the remaining 4 cases were presumptively diagnosed (cases 4, 8, 10 and 11). A high-field 1.5 T scanner was used in 8 patients (cases 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10 and 11), while a low-field 0.25 T scanner was used in the remaining 3 patients (cases 5, 6 and 9).

In 8 dogs, breed predispositions for other disease conditions and additional considerations gave cause for the attending clinician to obtain neuroimaging of the spine and/or brain, even though NA was the most likely diagnostic possibility, in addition to CSF collection for laboratory analyses under the same general anaesthetic. In the remaining 3 cases (1, 5 and 9) signs of encephalitis eclipsed those referable to spinal cord dysfunction, and MRI of the brain was considered essential to fully characterize the nature and extent of the cerebral disease process. In general, only areas of neuroanatomical dysfunction were imaged, based on detailed neurological assessment of the patient. As a result, none of the imaging studies included the entire CNS. MR imaging was conducted at variable time points after the first onset of clinical signs (1–31 days; unknown in 2 cases).

Results

Signalment, clinical signs and CSF cytology, serology and qPCR data are tabulated together with detailed MRI observations for all 11 cases (Table 1). The median age at presentation was 7 months (range 2–120 months). Six were small purebred dogs while the remaining 5 were medium to large dogs. Eight dogs were male; 3 were female. The median duration of clinical signs prior to presentation was 3 days (range 1–30 days; unknown for 2 cases). The most common clinical signs were hind-limb proprioceptive ataxia and/or paresis (7 dogs) and spinal hyperaesthesia (7 dogs), which was either focal (6 dogs) or diffuse (1 dog). Other findings included dull mentation (2 dogs), strabismus (2 dogs), urinary incontinence (2 dogs), tetraparesis (1 dog), tail paresis (1 dog), blindness (1 dog), facial twitching (1 dog), head tremor (1 dog), unusual behaviour (1 dog) and kyphotic posture (1 dog).

Table 1. MRI and CSF findings in 11 dogs with neuroangiostrongyliasis

3D, three-dimensional; CT, cycling threshold; d, dorsal; F, entire female; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; FN, female neutered; GRE, gradient echo; M, entire male; MN, male neutered; n/a, not available; s, sagittal; STIR, short tau inversion recovery; t, transverse; T, tesla; T1W, T1-weighted; T2*W, T2*-weighted; T2W, T2-weighted.

The brain was imaged in 6 cases. In 4 of these, the meninges of both cerebral hemispheres appeared hyperintense on T2W and T2W FLAIR sequences and had increased contrast enhancement on post-gadolinium T1W and T2W FLAIR images, suggestive of diffuse meningitis (Fig. 1A, B & C). In 1 dog (case 5), there were multifocal hyperintense areas in T2W and T2W FLAIR sequences; these areas were ill-defined, asymmetrical and distributed in both the grey and white matter of the cerebral cortex bilaterally, consistent with encephalitis (Fig. 2). The brain appeared normal in 2 cases; case 9, a dog with a sudden onset of head tremor 3-days prior to admission that had unremarkable CSF cytology (but was qPCR positive), and case 3, a dog with neuroanatomical localization to the lumbar spinal cord.

Fig. 1. High-field MR images from a 14-month-old French Bulldog with a definitive diagnosis of neuroangiostrongyliasis and mainly forebrain signs (case 1). Transverse (A) and dorsal (B) plane post-gadolinium T1W images of the cerebral hemispheres. Note the prominent contrast enhancement of the meninges in both cerebral hemispheres. A transverse T2W FLAIR image of the parietal lobes is shown in (C). Note the FLAIR hyperintensity associated with the meninges (red arrows), particularly in the left parietal lobe. Transverse post-gadolinium T1W image of the cervical spine is presented in (D); note the ring of contrast enhancement surrounding the spinal cord (red arrows).

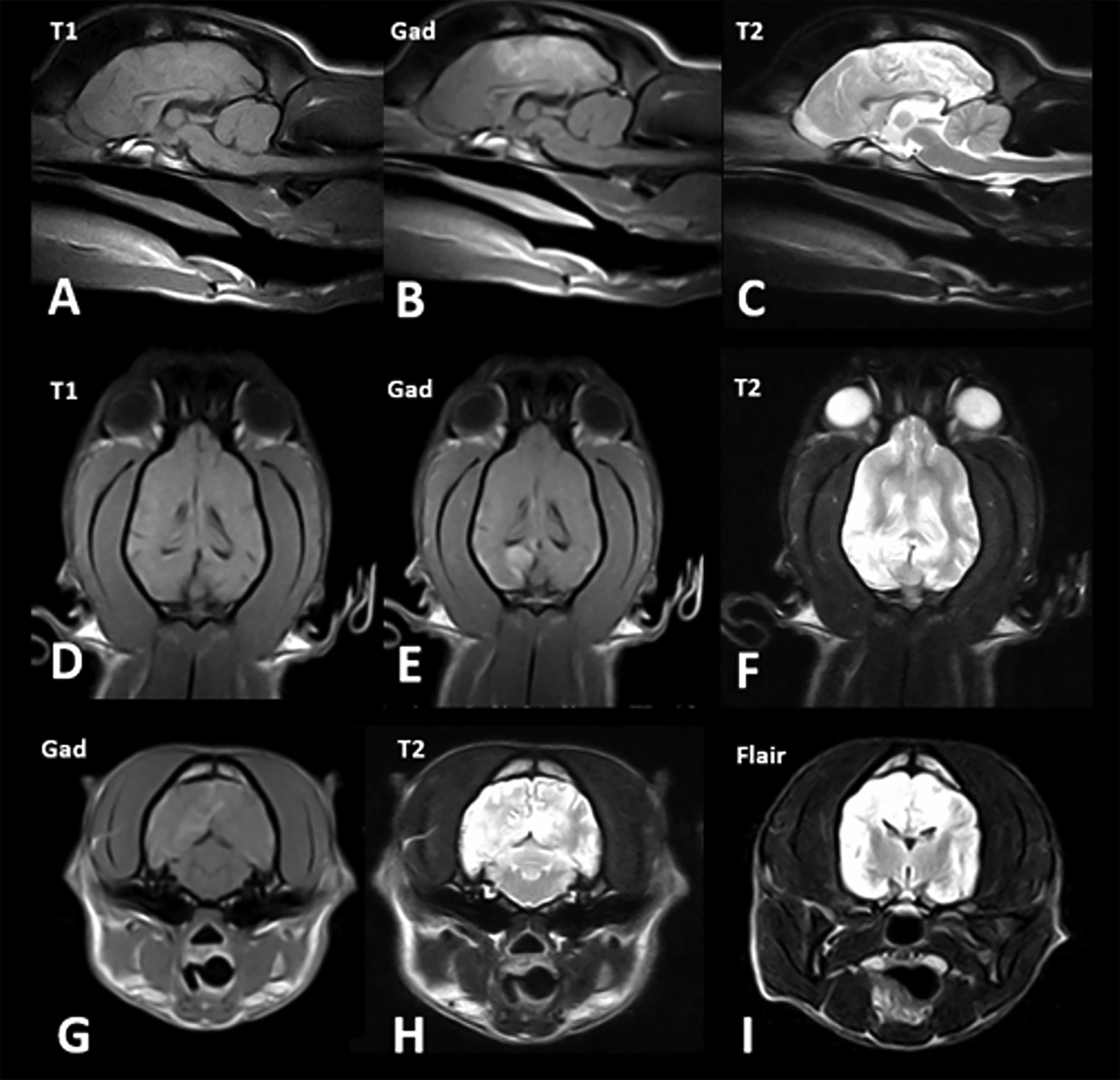

Fig. 2. Low-field MR images from a 1-year-old Jack Russell terrier crossbred dog with a definitive diagnosis of neuroangiostrongyliasis and forebrain signs (case 5). Sagittal images: T1W (A), post-gadolinium T1W (B) and T2W (C). Dorsal images: T1W (D), post-gadolinium T1W (E) and T2W (F). Transverse images: post-gadolinium T1W (G), T2W (H) and T2W FLAIR (I). There were multifocal areas of T2 and FLAIR hyperintensity that were ill-defined, asymmetrical and distributed in the grey and white matter of the cerebral cortex bilaterally. Grey and white matter distinction was poor. Severe, diffuse meningeal enhancement was present, mainly pachymeningeal in the forebrain and leptomeningeal in the parieto-occipital lobe region.

Various portions of the spinal cord and cauda equina were imaged in 9 cases. Two dogs (cases 1 and 2) showed hyperintensity of the cervical meninges on T2W and post-gadolinium T1W sequences, consistent with meningitis (Fig. 1D). In 6 patients, there were diffuse or patchy intramedullary hyperintensities of the spinal cord on T2W and T2W STIR images, which were sometimes contrast-enhancing on post-gadolinium T1W images (Figs. 3 & 4). Lesions were variable in their size and anatomical location (cervical in cases 2 and 7; thoracic in case 4; lumbar in cases 3, 6 and 10) and were associated with mild diffuse enlargement of the affected portion of the spinal cord in 2 patients (cases 3 and 4). These changes are consistent with myelitis, although in 1 dog (case 10) the changes were mild. In 2 dogs (cases 8 and 11), the spinal cord was considered normal despite neuroanatomical localization of dysfunction to the thoracolumbar region.

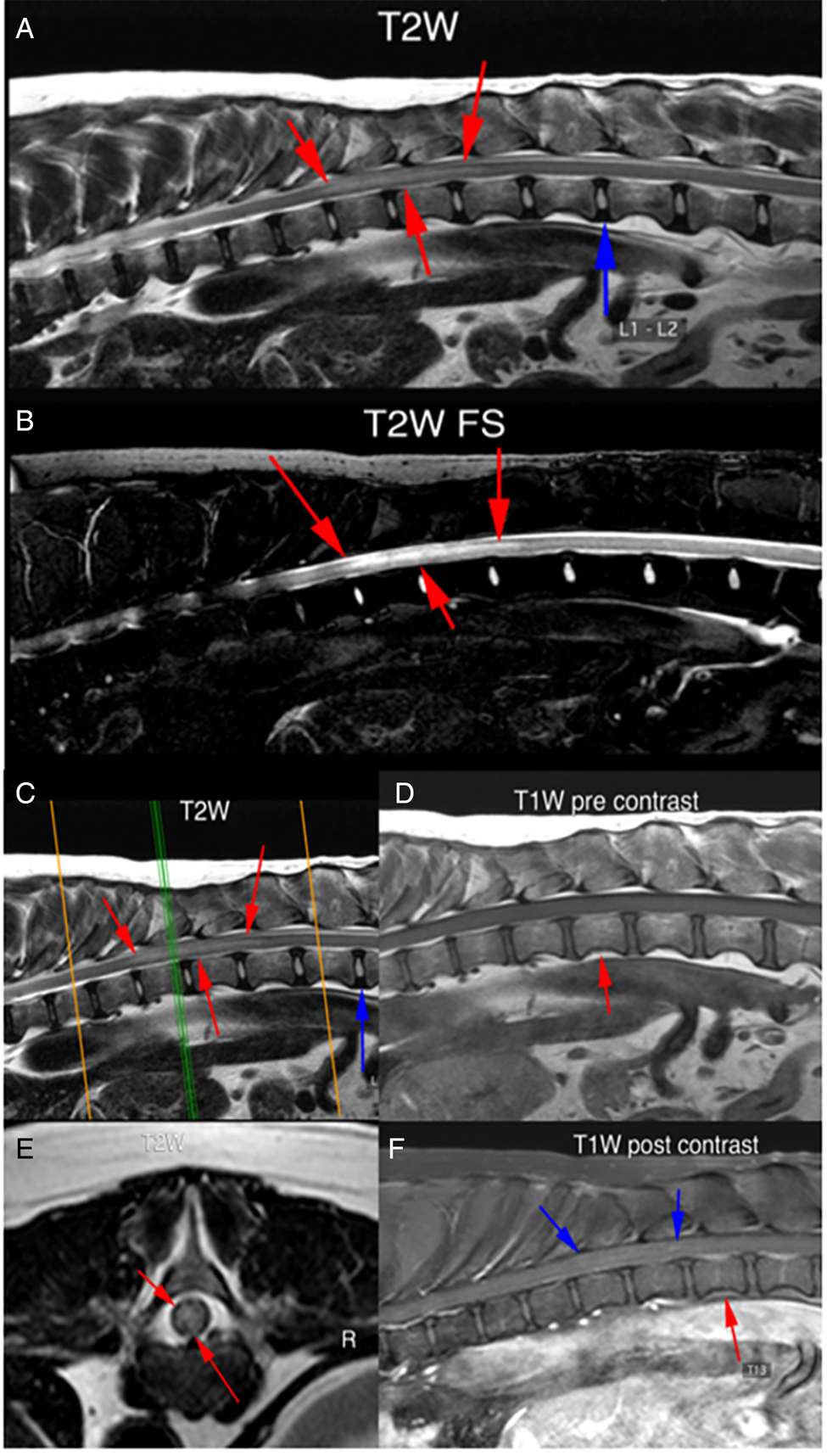

Fig. 3. High-field MR images from a 10-year-old Bull Arab dog with a presumptive diagnosis of neuroangiostrongyliasis and thoracolumbar signs (case 4). Sagittal T2W images (A and B) showing a diffuse intramedullary hyperintensity from the T10–T11 disc space to the T13 vertebra (red arrows). There is mild cord swelling at this site. Sagittal T2W image (C); the green line marks the point where the spinal cord was transected to obtain the transverse view (E). The intramedullary hyperintensity can be seen (red arrows). Sagittal T1W (D) and post-gadolinium T1W (F) images showing subtle streaky contrast enhancement within the spinal cord (blue arrows). The red arrows denote the T13 vertebral body.

Fig. 4. Low-field MR images from a 7-month-old Dalmatian with a definitive diagnosis of neuroangiostrongyliasis and lumbosacral signs (case 6). T2W sagittal (A) and transverse (B) images are presented. There is a focal, ill-defined T2 hyperintensity in the spinal cord at the level of L2-L3 vertebrae (orange arrows).

Discussion

This report provides the first description of MRI observations in the CNS of dogs with NA. One limitation is that dogs with classical clinical features of NA (young dogs with a history of snail ingestion, tail weakness, incontinence, and a mix of upper and lower motor neuron hind-limb paresis and spinal hyperaesthesia, which initially affects the lumbosacral area but subsequently ascends to become thoracolumbar and cervical) are not usually subjected to MRI; instead, these cases are typically diagnosed with NA based on CSF collection and analysis, with antibody and nucleic acid testing. This is reflected by a higher median age of dogs at presentation in this case series compared to a large database of Australian cases (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Pai, Churcher, Davies, Braddock, Linton, Yu, Bell, Wimpole, Dengate, Collins, Brown, Reppas, Jaensch, Wun, Martin, Slapeta and Malik2020). In companion animal practice, an MRI examination is an expensive procedure requiring a relatively long period of general anaesthesia. It does not provide a definitive diagnosis but rather a picture of the anatomical extent and severity of the disease, with some differentiation of meningeal vs parenchymal involvement, and the potential to detect haemorrhagic tracts indicative of larval migration. The 11 MRI studies reviewed here were from 4 atypical ‘encephalitic’ neurologic presentations and 7 more classic ‘spinoradicular’ cases (Barratt et al., Reference Barratt, Chan, Sandaradura, Malik, Spielman, Lee, Marriott, Harkness, Ellis and Stark2016).

Interestingly, 4/6 patients subjected to brain imaging showed at least some MRI evidence of meningoencephalitis, even in patients that presented primarily for spinal abnormalities and radicular pain. The brain appeared unremarkable in the only case where it was imaged in the absence of clinical evidence for prosencephalic dysfunction. Patients with neurologic signs that localized to the spinal cord showed changes suggestive of meningitis and/or myelitis, except for 2 cases where no abnormalities could be detected despite examination using a high-field MRI scanner. These changes indicative of meningoencephalomyelitis are consistent with necropsy findings in infected dogs, comprising of widespread eosinophilic meningitis and granulomatous encephalomyelitis associated with larvae and larval fragments (Jindrak and Alicata, Reference Jindrak and Alicata1970; Mason et al., Reference Mason, Prescott, Kelly and Waddell1976). Inflammation is likely secondary to mechanical tissue damage and microscopic haemorrhage from larval migration through the CNS parenchyma and meninges, as well as eosinophilic chemotaxis mediated by various larval antigens (Jindrak and Alicata, Reference Jindrak and Alicata1970; Mason et al., Reference Mason, Prescott, Kelly and Waddell1976; Ishida and Yoshimura, Reference Ishida and Yoshimura1990, Reference Ishida and Yoshimura1992; Barratt et al., Reference Barratt, Chan, Sandaradura, Malik, Spielman, Lee, Marriott, Harkness, Ellis and Stark2016). In addition, the release of neurotoxic proteins from eosinophils causing damage to surrounding tissue may also contribute to the MRI findings observed (Fredens et al., Reference Fredens, Dahl and Venge1985; Perez et al., Reference Perez, Capron, Lastre, Venge, Khalife and Capron1989).

Abnormalities were seen in both the brain and cervical spinal cord in all cases where both regions were imaged together, consistent with the cranial movement of larvae from the cord to the brain (Lunn et al., Reference Lunn, Lee, Smaller, Mackay, King, Hunt, Martin, Krockenberger, Spielman and Malik2012). Given the neuroanatomic predilection of larvae for the cauda equina in dogs, it is perhaps surprising that no MRI abnormalities in this region were reported in the 5 cases where the lumbosacral spine was imaged, despite 2 patients (cases 6 and 11) exhibiting characteristic signs of lumbosacral nerve root involvement. It is possible lesions may have been missed in case 6 due to the use of low-field MRI and lack of post-contrast sequences, but such consideration does not apply to case 11 where high-field post-contrast T1W images were obtained. Perhaps the explanation is that the larvae, initially present preferentially in the cauda equina region, had migrated cranially by the time the dogs were assessed neurologically and scheduled for an MRI scan, with the resolution of any associated tissue inflammation.

Overall, the information from the MRI examinations was consistent with the neuroanatomical localization for 8/11 dogs; no MRI abnormalities were detected in the remaining 3 dogs despite clinical evidence of spinal cord disease. None of the MRI studies showed signs specifically indicative of larva migrans as seen in some human patients, such as worm migration tracks and microhaemorrhagic lesions (Kanpittaya et al., Reference Kanpittaya, Jitpimolmard, Tiamkao and Mairiang2000; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Ma, Ma, He, Ji and Yin2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kuo, Lo, Huang, Wang and Wang2014), despite the use of GRE sequences in some cases. The smaller size of the canine brain and spinal cord and limitations of the low-field 0.25 T scanner used in 3 cases may have reduced the sensitivity of the examinations, making such lesions impossible to discern. As such, MRI is currently an inexact tool to distinguish canine NA from other inflammatory diseases of dogs causing meningoencephalomyelitis, such as meningoencephalitis of unknown origin (Granger et al., Reference Granger, Smith and Jeffery2010), idiopathic eosinophilic meningoencephalitis (Salvadori et al., Reference Salvadori, Baroni, Arispici and Cantile2007; Henke et al., Reference Henke, Vandevelde, Gorgas, Lang, Oevermann, O'hara and Berrill2009; Windsor et al., Reference Windsor, Sturges, Vernau and Vernau2009; Cardy and Cornelis, Reference Cardy and Cornelis2018), cryptococcosis (Sykes et al., Reference Sykes, Sturges, Cannon, Gericota, Higgins, Trivedi, Dickinson, Vernau, Meyer and Wisner2010), neosporosis (Parzefall et al., Reference Parzefall, Driver, Benigni and Davies2014) and toxoplasmosis (Lamb et al., Reference Lamb, Croson, Cappello and Cherubini2005). Ideally, 3 T scanners in conjunction with the use of SWI sequences could be employed in future cases to provide increased anatomic detail and sensitivity for haemorrhagic products. Such studies might enhance our ability to detect subtle changes associated with larval migration.

It is of great interest that 1 dog (case 9) with normal MRI findings had abundant A. cantonensis DNA in the CSF (CT 23.8), despite negative ELISA serology and unremarkable CSF cytology. The most parsimonious explanation is that this case presented early in the disease course, prior to the development of detectable inflammation or host immunological response. Although qPCR data is lacking, we suspect the same explanation may apply to the other patients with normal MRI findings (cases 8 and 11), although case 11 is more difficult to explain considering the relatively long duration of clinical signs prior to the MRI examination.

Limitations of our study include its retrospective nature, and the variable and relatively early period in which MR imaging was obtained following the onset of clinical signs. Serial MRI scans of human patients taken over the entire clinical course of NA have established that MRI lesions appear most severe 5–8 weeks after ingestion of infective larvae (following an incubation period of 3–9 days) (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Ma, Liang, Ji and Gan2005). Of course, the different time-course of NA in humans v dogs must be kept in mind when extrapolating this finding to canine NA. Unfortunately, we do not yet have sufficient data to correlate CSF cytology, serology, qPCR and MRI findings with the onset and severity of clinical signs in canine patients, although it is interesting that the dog with arguably the most severe MRI lesions (case 5) also had the longest duration of clinical sings prior to its MRI examination (4 weeks). Serial MRI scans in canine patients would be required to properly investigate the time course of changes, but the high cost and requirement for general anaesthesia make this likely cost-prohibitive in a veterinary setting. Sequential MRI studies in dogs with confirmed NA would help us better understand the relationship between imaging findings, disease progression and the response to therapy.

Conclusions

MRI is currently a relatively sensitive but nonspecific modality of some value in the diagnosis and characterization of canine NA. Imaging findings reflect meningeal and/or parenchymal inflammation of variable portions of the CNS, with the area of involvement generally consistent with the neuroanatomical localization. In light of these findings, we recommend NA be included in the differential diagnosis of dogs with MRI evidence of focal or diffuse meningitis, myelitis and/or encephalitis, especially in endemic areas. In such cases, the collection of CSF for cytological analysis, A. cantonensis serology and qPCR testing is strongly recommended. It should be noted that some dogs with NA diagnosed using qPCR had normal MRI examinations, so a normal MRI study does not preclude a diagnosis of canine NA. In dogs with so-called idiopathic eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, specific testing for A. cantonensis and A. vasorum using serology and qPCR, and for other potential pathogens using next-generation sequencing (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Sample, Zorn, Arevalo, Yu, Neuhaus, Federman, Stryke, Briggs, Langelier and Berger2019), would be a worthwhile undertaking.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jody Braddock, Georgina Child, Christine Griebsch and Joyce Chow for their assistance in obtaining case material for this project.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None

Ethical standards

Not applicable