INTRODUCTION

Infection with parasites and pathogens represents one of the strongest and most dynamic selective forces for the evolution of organisms. Co-evolution between hosts and parasites is supposed to lead to an evolutionary arms race, which was denoted as the “Red Queen” process by van Valen (1973). The species composition of parasitic communities is influenced by various ecological factors, such as the occurrence of susceptible intermediate and final hosts, or suitable environmental conditions for parasite transmission. Consequently, different host populations are often exposed to dissimilar communities of infectious agents. Spatially distinct populations of a given host species are therefore expected to evolve different defence mechanisms that are specifically adapted to the local parasite fauna. On the other hand, parasites are also under selection pressure from their host's defence strategies.

The susceptibility of spatially separated host populations to their sympatric and allopatric parasites has frequently been investigated in invertebrates (e.g. Lively, 1989; Ebert, 1994; Imhoof and Schmid-Hempel,1998; Altizer, 2001; Kraaijeveld and Godfray, 2001; Kurtz et al. 2002), vertebrates (e.g. Ballabeni and Ward, 1993; Dufva, 1996; Oppliger, Vernet and Baez, 1999; McCoy et al. 2002; Criscione and Blouin, 2004) and plants (e.g. Mutikainen et al. 2000; Kaltz and Shykoff, 2002; Thrall, Burdon and Bever, 2002). In fact, local adaptation phenomena were found to act in different directions: many studies revealed that parasites usually are best adapted to the most common genotypes within a local host population (Lively and Dybdahl, 2000) and perform less successfully, in terms of infectivity or host exploitation in individuals of the same species from geographically distant populations. Investigations of other model systems failed to detect any influence of host and parasite origin, whereas in a large third group of studies parasites were found to be locally maladapted, indicating a local adaptation of the host. In the latter case, individuals of a local host population have a selective advantage over immigrating conspecifics. As a consequence, locally dissimilar host-parasite coevolution might result in a reduction of gene flow between populations and, therefore, parasites could be regarded as an important driving force in ecological diversification and speciation.

Population differences that provide protection against parasites may be based on traits that enable the avoidance or clearance of an infection, or the reduction of the negative impact of an established infection on host fitness. The presumably most important tool to fulfill these tasks is the immune system. In vertebrates there are two branches of the immune system, innate and adaptive (or acquired) immunity (Janeway et al. 1999): innate immunity acts as a first line of defence against invading pathogens. This branch of immunity is evolutionarily ancient and already present in invertebrates. Although still generally regarded as rather unspecific, this notion, as well as its clear separation from adaptive immunity, is currently under debate (Flajnik and Du Pasquier, 2004; Kurtz, 2005). Vertebrate acquired immunity that is responsible for specific pathogen recognition after previous immunization, is based on the production of highly specific antibodies and the formation of immunological memory (Janeway et al. 1999). A crucial step for the development of an acquired immune response is the presentation of parasite-derived peptides by molecules of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Genes of the MHC are highly polymorphic at the level of populations (Klein, 1986) and in several cases associated with susceptibility to (locally) prevalent parasites (Briles, Stone and Cole, 1977; Hill et al. 1991; Godot et al. 2000).

Three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.) have become prime vertebrate model organisms to study host-parasite coevolution. In northern Germany, these small fish have been shown to form numerous genetically distinct populations (Reusch, Wegner and Kalbe, 2001), with especially high divergence between different types of habitats (i.e. brackish/marine, lakes and rivers), which also harbour different compositions of parasite species (Kalbe, Wegner and Reusch, 2002). Moreover, diversity in stickleback MHC class II genes differed between populations of these habitat types, which correlated with the diversity of the natural macroparasite fauna (Wegner, Reusch and Kalbe, 2003a). Field studies and laboratory experiments revealed that higher individual resistance against multiple parasite infections and supression of parasite growth was related to certain MHC class II characteristics (Wegner et al. 2003a,b; Kurtz et al. 2004).

On the level of populations, one would expect that G. aculeatus from different habitat types have optimized their immune system to cope with sympatric parasites of their particular environment. To test this assumption, we exposed naïve, laboratory bred offspring of sticklebacks from a lake and a river population, as well as F1 hybrids between both populations, to infectious stages (cercariae) of the common eye fluke Diplostomum pseudospathaceum. These digenean trematodes reproduce in the gut of gulls and terns, which excrete the eggs with the faeces. After development in water, miracidia hatch, locate, and penetrate Lymnaea stagnalis snails, the first intermediate hosts, where they develop into sporocysts and produce cercariae. These leave the host snails in enormous numbers and infect freshwater fish as second intermediate hosts, in which they inhabit the eye lenses. Eye flukes are known to cause mortality in fish populations (Pennycuick, 1971; Lester, 1977; Kennedy and Bourroghs, 1977; Kennedy, 1984; McKeown and Irwin, 1997), mainly by inducing increased predation by piscivorous birds, like the parasites' definitive hosts (Chappell, Hardie and Secombes, 1994). Eye flukes are highly prevalent in lake sticklebacks, but usually absent in fish from flowing waters in northern Germany (Kalbe et al. 2002). The aims of this study were to evaluate whether sympatric and allopatric hosts differ genetically in susceptibility to infection. Importantly, we wanted to relate potential differences in infection to innate or adaptive immunity. We thus compared infection success and immune activation after single and repeated exposures to cercariae. We further analysed several morphological parameters of the exposed fish in order to estimate the impact of the parasite on the body condition and physiological status of sympatric and allopatric sticklebacks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sticklebacks and parasites

Sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.) were caught in autumn from natural populations of 2 different habitat types in Schleswig-Holstein (northern Germany), the river ‘Schwale’ and the lake ‘Vierer See’ (for geographical location see Kalbe et al. 2002). These two populations are not naturally connected with each other. After catching, the fish were kept under winter conditions in the lab for 3 months before they were transferred stepwise during another 2 months, to a temperature of 18 °C and a day[ratio ]night rhythm of 14 h[ratio ]10 h, which corresponds to natural breeding conditions.

For use in the experiments, we raised F1 offspring from these two populations, which will be denoted as ‘S’ and ‘V’, respectively. We further bred hybrids (denoted as ‘H’), using either S males and V females or the reversed constellation, to enable the identification of potential maternal effects.

For breeding, males were housed individually in 16 L tanks with constant water exchange (1 L per h) and provided with sand and artificial nesting material. Females were kept in groups of 10 fish and were introduced singly into a male's tanks for 30 min for spawning. Egg clutches were then removed and incubated in aerated well water at 18 °C in 1 L glass jars for 8 days. Water was exchanged every second day and Malachite Green (0·1 ppm) was added to prevent fungal infection. Hatched fry of the whole egg clutch was kept in 16 L tanks until an age of 6–8 weeks, when the offspring were divided into groups of 20 fish per tank. Freshly hatched fish were fed daily with naupliae of Artemia salina, whereas older juvenile fish and adults received frozen chironomid larvae and cladocerans ad libitum for 5 days per week.

Cercariae of the digenean trematode Diplostomum pseudospathaceum (Niewiadomska, 1984) were obtained from naturally infected pond snails Lymnaea stagnalis collected in autumn in a lake belonging to the same drainage system as the Vierer See. Snails were kept in the lab at 18 °C with a daily light period of 14 h and were fed with washed lettuce and frozen chironomid larvae ad libitum.

Design of the experiment

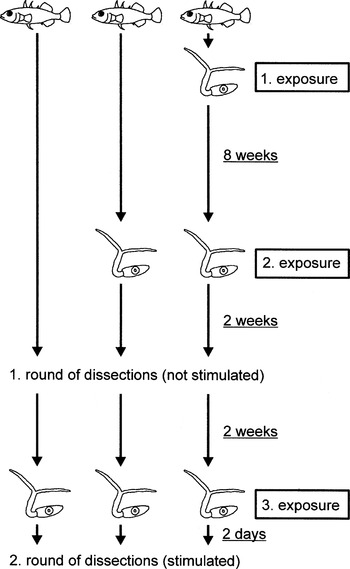

The whole experiment comprised 3 rounds of infection, and 2 rounds of dissection (Fig. 1). To enable sufficient time for an adaptive immune reaction to develop, the first and the second rounds of infection were separated by 8 weeks. The first round of dissection (including about half of the fish in equal amounts from all families and treatments) was performed 2 weeks after the second infection, i.e. 10 weeks after the first infection. By contrast, the second round of dissection (i.e. the remaining fish, 2 weeks after the first dissection round) was only 2 days after the preceding third round of infection. In this way, metacercariae establishing from this round of infection will be distinguishable by size from previous infections. Moreover, exposure immediately before the second round of dissection may lead to a stimulation of immune reactions, which would then still be measurable, but might not be active long after the parasites have reached the eye lenses. We included sham-treated (i.e. not exposed) fish in all but the third round of infection in order to gain maximal statistical power for our main question, which was the likelihood of infection resulting from the last, third round of infection. If adaptive immunity is relevant, infection success was here expected to depend on the prior experience of the fish: no previous contact with the parasite (i.e. only innate defences), 1 previous exposure, and repeated previous exposure with a potentially boosting effect on adaptive immunity. Assignment of fish to the different treatment groups was random and balanced within families, but without consideration of sex, since in immature fish, males and females cannot be distinguished accurately.

Fig. 1. Graphical representation of the experimental design.

Experimental infections

To obtain D. pseudospathaceum cercariae for experimental infection of sticklebacks, infected snails were placed individually into a glass beaker that contained 50 ml of tap water and was brightly illuminated, as light is known to stimulate cercarial shedding. After 90 min, equal amounts of cercariae obtained from 5 snails were pooled and gently mixed. From this suspension, 20 cercariae were transferred with a Pasteur pipette into disposable Petri dishes. After another 90 min, these 20 cercariae, together with their Petri dish, were immersed into a small tank containing 1 stickleback and 1 L of tap water. This procedure ensured that all experimental hosts received infective parasites of the same age (i.e. between 90 min and 3 h), probably the optimum age of infectivity for cercariae at 18 °C, which had been determined as the period between 0 and 5 h at 14 °C (Whyte, Secombes and Chappel, 1991). Thereafter, fish remained individually in the infection tanks for 24 h before they were returned to 16 L aquaria into their original sibship groups.

For the first round of infection, 7 fish from each tank/sibship, were exposed to a dose of 20 cercariae, while the remaining 13 fish were treated similarly, but without addition of cercariae (sham exposed). Exposed and sham-treated fish of the same sibship were kept in the same tank, but distinguished by clipping the tip of different dorsal spines. Eight weeks later, fish were weighed (to the nearest 0·1 mg) and the total body length (to the nearest mm, respectively). They were now marked by an individual code of clipped dorsal and lateral spines, before the eye lenses of all fish were checked in vivo under a dissection microscope to count established D. pseudospathaceum metacercariae. Previous comparisons of counts in vivo and after dissection revealed that up to 10 metacercariae per eye lens can be determined by a trained observer with high reliability. Thereafter, all previously exposed fish and 7 fish from the sham group were again infected with 20 cercariae as described above.

Two weeks after the second exposure, we started the first round of dissection. On each of 7 consecutive days we randomly selected 1 sibship per population (V, S and H), for dissection of about half of the fishes (i.e. 3 or 4 fish each from the sham, singly and doubly exposed groups). In the second round of infection, 2 weeks later, the remaining fish were dissected in the same order of sibships. This time, however, fish of all treatment groups had received a dose of 20 cercariae 2 days prior to dissection (these fish will therefore be denoted as ‘stimulated’).

Measurements and analysis

Fish were stunned by a blow on the head and total length (to the nearest mm) and weight (to the nearest 0·1 mg) were determined before cutting off the tail to obtain blood samples from the caudal vein into heparinized micro-capillaries. After decapitation, the body cavity was opened and head kidneys, liver, spleen and gonads were removed. From the head kidneys, the major lymphatic organ in teleost fish (Press and Evensen, 1999), cell suspensions were prepared and washed as described previously by Scharsack et al. (2004). The other organs were weighed (to the nearest 0·1 mg), and liver and spleen were stored at −85 °C for further analysis. For determination of infection rates, eye lenses were removed and metacercariae were counted under a dissection microscope.

Blood in micro-capillaries was centrifuged at 2500 g and 4 °C for 10 min. Before the plasma samples were stored at −85 °C for further analysis, the height of the supernatant and the underlying cellular fraction were measured (to the nearest 0·1 mm) in order to calculate the haematocrit value, a function of the relative erythrocyte volume.

Although all fish were kept under identical constant light and temperature conditions, some individual females started to develop egg clutches during the experiment. Hence, for morphometric calculations, the weight of gonads was subtracted from total body weight to level out individual differences in sex and sexual maturation; calculation of all indices was based on the weight without gonads (WWG). The hepatosomatic index (IH), as a measure of the energy status (Chellappa et al. 1995), was determined according to the formula IH=(weight of liver in mg)×100/(WWG in mg). The splenosomatic index (IS), as a rough estimate of the immune status, was calculated in a similar way. The condition factor (cf) was determined by the method of Frischknecht (1993) according to formula cf=100×WWG/Lb (WWG in g, fish length L in cm and the exponent from the linear regression analysis b=2·83 of log-transformed values of WWG and L).

Cell counts and respiratory burst assay

Suspensions of freshly isolated head kidney leucocytes (HKL) were prepared for analysis by flow cytometry as described by Scharsack et al. (2004). After being washed and adjusted to a uniform volume of 1 ml, aliquots of the HKL suspensions were transferred into tubes and supplemented with 2×105 green flourescent standard beads (4 μm; Polyscience, USA) and propidium iodide (2 mg/L; Sigma-Aldrich). Measurements were performed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) using the CellQuest Pro 4.02 software for acquisition and analysis. Forward and side scatter values (FSC/SSC) of at least 10000 events were acquired in linear mode, fluorescence intensity at 530 nm (beads) and 585 nm (propidium iodide) was acquired on log-scale. Granulocytes and lymphocytes were identified by their characteristic FSC/SSC profiles (Scharsack et al. 2004) and their absolute numbers in individual samples were calculated on the basis of the number of detected standard beads (Pechhold, Pohl and Kabelitz, 1994). Dead cells (propidium iodide positive) and cellular debris were excluded from further calculations.

As one of the most important effector mechanisms of the innate immune system, we quantified the respiratory burst reaction of HKL in a lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay (CL) modified after Scott and Klesius (1981), as described by Kurtz et al. (2004). The CL assay was performed in vitro using a 96-well microtitre plate luminometer (Berthold, Germany) with 2×105 cells/well. Phagocytosis and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was initiated by addition of zymosan particles and was measured for 3 h at 18–20 °C. Whenever enough HKL from individual fish was available, the reaction was carried out in duplicate together with a control (no zymosan) to estimate spontaneous ROS production.

Data analysis

The original sample comprised 7 stickleback families from each population (V, S and H) with 20 fish each, i.e. 420 fish. Ten fish died before exposure, leaving 410 fish for the experiment. During the period of 100 days between the first exposure and the final dissection, 7 sticklebacks died and were excluded from further analysis, so that the final sample consisted of 403 fish. Of these, 189 were dissected during the first round of infection and 214 during the second round. Infection success (i.e. the number of metacercariae in the eyelenses) resulting from the first round of infection (‘1. exposure’) was based on 142 fish (other fish were sham exposed during the first round of infection) which included 63 fish that were dissected during the first dissection round and 79 fish dissected during the second round. Infection success resulting from the second round of infection (‘2. exposure’) was based on 285 fish (other fish were sham exposed during the second round of infection), which included 128 that were dissected during the first dissection round and 157 fish dissected during the second round. Finally, infection success resulting from the third round of infection (‘3. exposure’) was based on all 213 fish dissected during the second round, since all these fish had been exposed 2 days previously.

Using analyses of variance (ANOVA), we examined whether the population of origin (‘population’: V, S or H) or previous exposure (‘infection status’: sham, 1×exposed, 2×exposed) affected the infection success. We also included fish gender (‘sex’: male, female) and the sibship the fish belonged to (nested within population) into the model, as well as all possible interaction terms. All interactions were left in the models, although only significant interactions are shown in the tables. To identify potential maternal effects on infection, we calculated ANOVA models for the hybrid fish that contained, instead of the factor ‘population’, the population of origin of the mother (S or V). Further ANOVA models were calculated to analyse a possible relation between the above factors and measures of immune activity and body condition. In addition to these factors, the models also contained the round of dissection as a factor, since immune parameters of fish dissected during the second round might have been stimulated by the recent parasitic exposure. Sample sizes were reduced for haematocrit, respiratory burst, and G[ratio ]L ratio because from several fish either insufficient amounts of blood or of head kidney cells could be obtained for accurate measurements.

We checked for normal distribution of the residuals from the models, with Shapiro-Wilk tests. We used square-root data transformation for the ‘respiratory burst’ and Box-Cox transformations for G[ratio ]L ratio, HSI and SSI. After that, all residuals were normally distributed (P>0·20, ‘growth’: P>0·10), except for ‘2. exposure’ (P<0·01) and SSI (P<0·001), where we could not find an appropriate transformation. We nevertheless decided to do parametric statistics also for these variables, because visual inspection of the distribution did not show any severe directed deviations from normality (the statistical power to detect deviations from normality in our data set is large due to huge sample sizes). All reported tests are 2-sided, with a P-value of 0·05 regarded as the level of significance. For representation in the figures, means and confidence limits were transformed back where necessary.

RESULTS

Infection success

Infection success of D. pseudospathaceum trematodes after experimental exposure to 20 cercariae differed strongly between the fish populations (Fig. 2A). Laboratory-raised offspring of lake sticklebacks (V) always harboured the lowest number of established D. pseudospathaceum, whereas the highest number of metacercariae was recovered from eye lenses of river fish (S). F1 hybrids (H) of the 2 habitat types harboured an intermediate number of parasites. This pattern was repeatable for all 3 rounds of experimental infection (Fig. 2 A–C). Analyses of variance showed that the population of origin explained by far the largest proportion of the variation in infection success (Table 1). In addition, infection success also varied significantly among the fish sibships and between the genders. Females were more strongly infected, which was significant for the first and the third round of exposure (Table 1). To find out whether maternal effects may influence infection, we analysed infection success in the hybrid fish with regard to the population of origin of the mother. There was no significant difference for any of the 3 rounds of exposure between fish whose mothers were from the S or V population (ANOVA, P>0·10).

Fig. 2. Diplostomum pseudospathaceum infection of lab-bred sticklebacks derived from a lake population, a river population and the F1 hybrid. D. pseudospathaceum occurs naturally only in the lake population. Bars show mean parasite loads (with 95% confidence limits) resulting from experimental exposure of individual sticklebacks to 20 cercariae each. (A) Infection of naïve fish, i.e. without previous exposure (cf Table 1, ‘Infection 1’). (B) Infection of fish that had been exposed for the first or second time (cf Table 1, ‘Infection 2’). (C) Infection of fish that had been exposed for the first, second, or third time (cf Table 1, ‘Infection 3’).

Table 1. Results of analyses of variance (ANOVA) for the effect of fish population of origin, previous parasitic exposure, dissection round, fish sex and fish sibship on Diplostomum pseudospathaceum infection (All possible interaction terms are included in the models, but only shown where significant.)

To evaluate the potential relevance of adaptive immunity against this parasite, we were interested in the effect of prior experience with the parasite on subsequent infection. Comparisons of infection success are valid only between different treatment groups (naïve or previously exposed), gender, sibships or habitat types within 1 round of exposure, where all fish received cercariae from the same pool. Differences between the 3 rounds of exposure are basically not comparable, because they might also be due to differences in viability and clonal composition of the infective parasite stages. In contrast to expectation for adaptive defences, we found only a marginal reduction in parasite loads for fish that had previously been exposed (Fig. 2B). This effect was not statistically significant for the second round of infection, whereas it was significant for the third round of infection (Fig. 2C), where fishes had encountered the parasite up to twice before, over a time-span of 3 months (Fig. 1). A post-hoc comparison revealed that only this group of fish had significantly more parasites than the previously not exposed fish (Tukey HSD, P<0·05).

Immunological and morphological measurements

The differences between the stickleback populations in D. pseudospathaceum infection after experimental exposure were paralleled by differences in measures of the innate immune activity (Fig. 3; Table 2). Head kidney cells obtained from sticklebacks of the lake population (V) showed a substantially higher respiratory burst reaction in vitro (Fig. 3B), which is an important measure of the strength of the innate immune system in fish. Hybrid fish were intermediate to purebred V and S fish. These population differences in the respiratory burst seemed to result only partially from a higher proportion of granulocytes (Fig. 3A), since population differences in the G[ratio ]L ratio were only marginally significant, leaving the activity status of the granulocytes as the main factor for the observed differences. Similar population differences were also observed for another measure of immunity: V fish had larger spleens (Fig. 3C) than S fish, hybrids were intermediate. The same pattern was observed for measures of condition, i.e. the hepatosomatic index (HSI; Fig. 3D), a measure of metabolic condition, the haematocrit, primarily a function of erythrocyte concentration (Fig. 3F), and the body condition factor (cf Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3. Measures of immunity and body condition of lab-bred sticklebacks derived from a lake population, a river population and the F1 hybrid. The fish were experimentally exposed to the eye fluke Diplostomum pseudospathaceum. The 2 different bars (with 95% confidence limits) for each population distinguish fish with or without a stimulatory exposure 2 days prior to dissecting and obtaining the measures of immunity and condition. Otherwise, fish with differing history of previous exposure were pooled, since there were no corresponding differences in the traits measured (cf Table 2). (A) Ratio of head kidney granulocytes to lymphocytes. (B) Respiratory burst of head kidney cells, measured in an in vitro chemiluminescence-enhanced assay. (C) Splenosomatic index, i.e. the weight of the spleen in relation to body weight. (D) Hepatosomatic index, i.e. the weight of the liver in relation to body weight, which is a measure of metabolic body condition. (E) Haematocrit value, representing the amount of cellular compounds in whole blood samples. (F) Body condition factor, as a function of fish length and fish weight.

Table 2. Results of analyses of variance (ANOVA) for the effect of fish population of origin, previous parasitic exposure, dissection round, fish sex and fish sibship on measures of fish immunity and body condition (All possible interaction terms are included in the models, but only shown where significant.)

The sexes differed in several parameters of immunity. Females showed a substantially stronger respiratory burst reaction, had a slightly higher G[ratio ]L ratio and a significantly higher haematocrit value. Females also had relatively larger livers, but a lower body condition factor.

There were no significant differences with regard to previous exposure for any of our measures of immunity and body condition. This indicates that single or repeated encounters with D. pseudospathaceum cercariae did not result in a lasting change in immunological activity of sticklebacks, at least for the measures obtained here. Moreover, infection with this parasite seems not to show any clear negative impact on energy reserves and body condition of the fishes under laboratory conditions. However, we found interesting differences in immune parameters between the two rounds of dissection. Fish dissected during the second round had stronger respiratory burst reactions, but a reduced G[ratio ]L ratio and haematocrit. Since these fish had obtained a parasitic exposure only 2 days previously, these changes might represent the recent stimulation of the immune system by the parasites.

DISCUSSION

Eye flukes of the genus Diplostomum are well known for their strong impact on fresh water fish populations. Mass infections with Diplostomum cercariae have been reported to kill young/small fish (Brassard, Rau and Curtis, 1982) and by reduction of visual capacity of their second intermediate hosts, the parasite interferes with feeding efficiency and predator avoidance (Crowden and Broom, 1980; Owen, Barber and Hart, 1993; Seppälä, Karvonen and Valtonen, 2004). These effects are probably responsible for parasite-induced mortality in wild and farmed fish, as detected in epidemiological studies (Pennycuick, 1971; Kennedy and Burrough, 1977; Lester, 1977; Kennedy, 1984; McKeown and Irwin, 1997). Diplostomum parasites may thus have the potential to drive the evolution of host defence strategies.

In the present study, we found that lab-bred sticklebacks from a lake population, where eye flukes occur with high prevalence, were less susceptible to infection with D. pseudospathaceum than fish from a river population. Since L. stagnalis, the host snail of this eye fluke, usually does not occur in flowing water, it can be assumed that sticklebacks from the river population were not exposed to this parasite for many generations.

Interestingly, F1 hybrids from both populations always ranged at intermediate infection levels, no matter whether the respective mother was of lake or river origin. This shows the genetic basis of this parasite resistance, while ruling out maternal effects. The clear distinction in susceptibility appeared already after the very first exposure of naïve hosts to infective stages of the parasite, indicating that higher resistance of sympatric lake fish was due primarily to the innate immune system. An innate immune mechanism of major relevance is the respiratory burst reaction, which is based on the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or superoxide anions (O2−) by granulocytes and macrophages. This reaction has been shown in vitro to kill diplostomules, the eye flukes' larval stages inside the fish (Whyte, Chappell and Secombes, 1989; Chappell et al. 1994). In the current study, the respiratory burst reaction was highest in sticklebacks from lakes, followed by F1 hybrids and was lowest in purebred river fish, clearly reflecting the pattern seen in infection rates. Additional evidence for the relevance of this immune response in the defence against Diplostomum can be deduced from the fact that ROS production increased 2 days after exposure to cercariae, compared to measurement of fish that were not recently stimulated. The apparently short period of increased respiratory burst activity is in line with the time-span during which the diplostomules are accessible to the immune system, since they reach the immunologically privileged eye lenses usually within less than 24 h (Whyte et al. 1991; Lyholt and Buchmann, 1996). Furthermore, higher respiratory burst intensity in lake fish seems to be a consequence of specific activation or efficiency of single cells rather than increased proportions of granulocytes, since the granulocyte to lymphocyte ratio did not differ significantly between fish of both habitat types. The observed decrease in granulocytes 2 days p.i. in the second dissection round might have been caused by migration of granulocytes from the head kidney to the penetrating diplostomules in the periphery. Besides the production of toxic ROS, fish granulocytes and monocytes are capable of encapsulating diplostomules (Ratanarat-Brockelmann, 1974).

Another striking immunological difference between sticklebacks from the different origins was the relative size of their spleen. Lake sticklebacks had much higher spleen weights than river fish, regardless of infection status. Hence, the actual size of this lymphatic organ does not seem to be a consequence of experienced contact with the parasite, but a general characteristic of these populations. Its potential role in protection against infection with D. pseudospathaceum thus remains to be demonstrated.

A single previous contact with D. pseudospathaceum did not lead to an increased protection of lake or river sticklebacks after an 8-week interval. This period was assumed to be sufficient for mounting an adaptive immune response because, in rainbow trout, specific antibodies against Diplostomum appeared 6 weeks after injection of homogenized cercariae (Whyte et al. 1987). Only a further exposure to the parasite 2 weeks later resulted in slightly reduced infection success. However, enhanced protection after previous exposure was unexpectedly small, and became significant only when all fish (i.e. both habitats and hybrids) were included in the analysis.

The apparently minor relevance of acquired immunity in the current study deserves further inspection, in particular in relation to previous studies in the same host, which showed remarkable associations of the local parasite species composition and abundance with MHC class II genes that are central to acquired immunity (Wegner et al. 2003a; Reusch and Wegner, unpublished observations). It remains to be shown whether local adaptation of MHC genetics might be more relevant under natural situations, compared to the experimental situation chosen here. For example, acquired immunity might become stronger when sticklebacks encounter Diplostomum cercariae continuously over an even longer time-span from spring to late autumn. Long-term accumulation of eye flukes is quite likely, since microsatellite studies revealed much higher clonal diversity of D. pseudospathaceum in sticklebacks than in sympatric first intermediate host snails (Rauch, Kalbe and Reusch, 2005). In rainbow trout, several repeated exposures or continuous exposition to Diplostomum cercariae have been shown to reduce infection rate (Höglund and Thuvander, 1990; Karvonen et al. 2005). Moreover, acquired immunity might be more relevant for defence against other species of parasites, or for defence against a combination of diverse parasite species (Wegner et al. 2003a,b; Kurtz et al. 2004).

Whyte et al. (1989) have shown in in vitro assays with serum from immunized rainbow trout that respiratory burst activity of macrophages as well as effectiveness of the complement system against diplostomules were increased in the presence of specific antibodies. Since the different levels of respiratory burst activity found in sticklebacks of different origin are not influenced by previous encounters with D. pseudospathaceum, one could speculate that natural antibodies might be a contributing factor. Lake sticklebacks may have higher levels of these pre-existing specific antibodies, or their affinity to diplostomules might be higher than in river fish, enhancing effector mechanisms of the innate immunity. Natural antibodies have already been found in goldfish as the basis for remarkable intra-specific differences in mortality from a bacterial pathogen (Sinyakov et al. 2002).

The results of this study contrast with the assumption that parasites perform generally better in their sympatric local host populations (Ebert and Hamilton, 1996). However, in numerous examples of host-parasite interactions no local adaptation of the parasite could be detected, and in several cases even the reverse pattern was found (Kaltz and Shykoff, 1998). Lajeunesse and Forbes (2002) discovered a regularity in these contradictory findings: parasites with a narrow host range, i.e. those which develop only in one or a few host species tend to become locally adapted, whereas in parasites with broad host range local adaptation is rather unlikely. Generalist parasites with the potential to infect several different species of host may hardly afford specialization on the locally most common genotype of only one of the many host species (Lively and Dybdahl, 2000). Eye flukes of the genus Diplostomum are normally rather unspecific with respect to their fish hosts (Sweeting, 1974; Chappell et al. 1994). Yet there are exceptions: the brain-encysting Diplostomum phoxini is restricted to only 1 fish species as second intermediate host, the European minnow Phoxinus phoxinus. Interestingly, parasite local adaptation does occur in diplostomatids of this species (Ballabeni and Ward, 1993). However, in contrast to those previous studies, we did not aim at delivering just another example of parasite local (mal-) adaptation here, in which case we would have chosen a reciprocal experimental design, exposing hosts with sympatric and allopatric parasite populations. Since we were rather interested in evolutionary adaptations of host immunity to the different parasite species that are present or absent in local populations, we compared a host population where Diplostomum does not occur, thus excluding evolution of this host population with that particular parasite species. Using sticklebacks from a fast flowing river ensured that fish from this population have not encountered eye flukes during their recent evolutionary history, because of the absence of suitable host snails.

The differences in immunity observed here may result from adaptation to local conditions in the two populations, such as the presence or absence of certain parasites, or more general adaptations to the different habitats, i.e. lake versus river. Lake fish had a higher basic immunocompetence, measured as respiratory burst activity and spleen weight, compared to river sticklebacks and their F1 hybrids, which ranged between the purebred fish. This probably reflects an adaptation to the higher abundance and species diversity of stickleback parasites in lakes (Kalbe et al. 2002; Wegner et al. 2003a). This would be in agreement with recent findings in different island populations of Darwin's finches, where investment to immunity correlated with parasite pressure (Lindström et al. 2004).

The current study may be seen as a first step towards identifying immunological correlates of the adaptation of hosts to parasites that differ between populations and habitats. It may thus help to bridge the gap between the purely mechanistic understanding of the immunological interaction between hosts and parasites, and the evolutionarily relevant variability in resistance that is observed among and within populations of hosts.

We wish to thank Withe Derner, Kerstin Brzezek and Anja Hasselmayer for assistance with dissections and running immunological assays. We further thank Gerhard Augustin, Dietmar Lemcke and Monika Wulf, who provided help in catching sticklebacks, collecting snails and maintaining several hundreds of fish in the lab. Furthermore, we thank Gisep Rauch, Joern Scharsack and Mathias Wegner for valuable and stimulating discussions.