INTRODUCTION

Fasciolosis is an important parasitic disease in animals and humans and is caused by the two valid species Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica, which are classically identified by morphological characteristics such as body length and width. Fasciola hepatica is mainly distributed in Europe, Americas, Oceania and Asia, while F. gigantica exists in Africa and Asia, and therefore the two species co-exist in some Asian countries (Torgerson and Claxton, Reference Torgerson, Claxton and Dalton1999). Although both F. hepatica and F. gigantica are hermaphroditic digeneans, they seem generally to reproduce bisexually by means of insemination due to mating with another individual in the bile duct of a definitive host. The two Fasciola species have been shown to be meiotically functional diploids (Sanderson, Reference Sanderson1953; Reddy and Subramanyam, Reference Reddy and Subramanyam1973) and yield haploid spermatids and ootids. Sperm injected into the uterus by mating enter oocytes in the entrance of the uterus. Fertilized eggs become mature in the uterus and are excreted from the genital pore. The two Fasciola species can also be clearly discriminated by differences in nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences, and mutations between the two species include 6 sites in the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) 1 region and 8 sites in the ITS2 region (Itagaki and Tsutsumi, Reference Itagaki and Tsutsumi1998; Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Kikawa, Sakaguchi, Shimo, Terasaki, Shibahara and Fukuda2005a).

Fasciola specimens intermediate between F. hepatica and F. gigantica in morphology have been found in Asian countries, including Japan (Watanabe and Iwata, Reference Watanabe and Iwata1954; Oshima et al. Reference Oshima, Akahane and Shimazu1968), India (Varma, Reference Varma1953), Korea (Chu and Kim, Reference Chu and Kim1967), the Philippines (Kimura et al. Reference Kimura, Shimizu and Kawano1984), Iran (Ashrafi et al. Reference Ashrafi, Valero, Panova, Periago, Massoud and Mas-Coma2006), Vietnam (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Sakaguchi, Terasaki, Sasaki, Yoshihara and Van Dung2009) and China (Peng et al. Reference Peng, Ichinomiya, Ohtori, Ichikawa, Shibahara and Itagaki2009), and also in Egypt (Periago et al. Reference Periago, Valero, El Sayed, Ashrafi, El Wakeel, Mohamed, Desquesnes, Curtale and Mas-Coma2007). Accurate species identification of these intermediate forms is difficult. Moreover, Asian Fasciola forms include aspermic diploid and triploid specimens that are meiotically dysfunctional and gynogenic (Moriyama et al. Reference Moriyama, Tsuji and Seto1979; Sakaguchi, Reference Sakaguchi1980; Terasaki et al. Reference Terasaki, Moriyama-Gonda and Noda1998). Aspermic specimens from Japan, Korea, Vietnam and China exhibited heterogeneity between F. hepatica and F. gigantica in nuclear ribosomal and mitochondrial DNA, suggesting that their origin may be hybridization between the two Fasciola species (Itagaki and Tsutsumi, Reference Itagaki and Tsutsumi1998; Agatsuma et al. Reference Agatsuma, Arakawa, Iwagami, Honzako, Cahyaningsih, Kang and Hong2000; Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Kikawa, Sakaguchi, Shimo, Terasaki, Shibahara and Fukuda2005 a,Reference Itagaki, Kikawa, Terasaki, Shibahara and Fukudab, Reference Itagaki, Sakaguchi, Terasaki, Sasaki, Yoshihara and Van Dung2009, Peng et al. Reference Peng, Ichinomiya, Ohtori, Ichikawa, Shibahara and Itagaki2009).

The present study was designed to clarify the possibility of interspecific hybridization between F. hepatica and F. gigantica by mixed infections in experimental animals and to address the question of reproductive isolation between the two Fasciola species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and snail hosts

Fasciola hepatica was isolated from the bile duct of infected sheep in Montevideo, Uruguay and maintained in a laboratory of the Biological Parasitology Unit of Institute of Hygiene, Uruguay using the snail host Lymnaea viatrix and a definitive host (sheep). Fasciola gigantica was isolated from the bile duct of naturally infected cattle sacrificed in a local abattoir in Lusaka, Zambia, and the flukes were accurately identified on the basis of morphological criteria such as ratio of body length and width (the ratio being more than 4) and DNA sequence in nuclear ribosomal ITS1 (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Kikawa, Sakaguchi, Shimo, Terasaki, Shibahara and Fukuda2005a), and they had many sperm in the seminal vesicles (spermatogenesis).

The snail host, Lymnaea ollula, which can be a common intermediate host of the two Fasciola species (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Fujiwara, Mashima and Itagaki1988, Reference Itagaki, Uchida and Itagaki1989), was collected in Naha and Uruma, Okinawa Prefecture, in Tazawako, Akita Prefecture, and in Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, where Fasciola infections in animals have not been detected. The snails were used for production of metacercariae of F1 and F2 generations as well as parental F. gigantica.

Experiments on hybridization between F. hepatica and F. gigantica

Metacercariae of F. hepatica were sent to the laboratory of Veterinary Parasitology, Iwate University, Japan and were used for hybridization experiments. The eggs of F. gigantica were shipped to the laboratory and kept at 27°C for miracidia to hatch out. Metacercariae of F. gigantica were derived from 200 snails of L. ollula exposed individually to 5–10 miracidia each and kept at 27°C for about 40 days.

Two goats of the Japanese Saanen breed, which is a common definitive host of F. hepatica and F. gigantica, were orally infected with 30 and 40 metacercariae each of both F. hepatica and F. gigantica and were sacrificed 7 months after infection by exsanguination under ketamine anaesthesia. Animal experiments carried out in the study were approved by the animal ethics committees of Iwate University and National Defense Medical College. From the bile ducts of the individual livers dissected out, 15 and 18 adult flukes were recovered and kept in 0·85% saline. These Fasciola worms termed the parental generation were identified to the species using the PCR-RFLP method (Ichikawa and Itagaki, Reference Ichikawa and Itagaki2010) and additional DNA sequencing as described below. In addition, to clarify insemination between F. hepatica and F. gigantica, intrauterine sperm were recovered from the individual flukes using a micropipette under a stereomicroscope and the species of the sperm was confirmed by the PCR-RFLP.

Experiments for F1 and F2 generations

Uterine eggs of the 33 parental Fasciola flukes obtained in the hybridization experiments were recovered individually and incubated at 28°C for 15 to 23 days. About 700 snails of L. ollula collected in Naha and Uruma were exposed to hatched miracidia of individual Fasciola worms and were kept at 27°C in the laboratory. However, snails of the Naha population unfortunately all died before producing cercariae, and only snails of the Uruma population that were exposed to miracidia derived from 1 parental adult (Fh no. 3) of F. hepatica and 3 parental adults (Fg no. 3, Fg no. 20, Fg no. 23) of F. gigantica produced sufficient metacercariae to be used for infection to final hosts. In order to obtain adult flukes of the F1 generation derived from the 4 parental Fasciola flukes, 4 groups of five 6-week-old male Wistar rats were each fed 20 metacercariae from 1 of the 4 parental flukes.

Uterine eggs were recovered from individual adult flukes of the F1 generation derived from parental Fh no. 3 and Fg no. 20 and were incubated at 28°C for 15 to 23 days. Hatched miracidia were exposed to L. ollula snails that had been collected in Kawasaki and Tazawako, and metacercariae were produced after 30 days. Twenty metacercariae each derived from Fh no. 3 and Fg no. 20 were orally given to 6 male 6-week-old Wistar rats, and adult flukes of the F2 generation were recovered from the rats after 23 to 26 weeks of infection.

Measurements and morphology of adult flukes obtained in experimental infections

Adult flukes obtained in experiments for F1 and F2 generations were put between 2 slide glasses with slight pressure, and then their body length and width were measured. Thereafter, the anterior parts including the vesicula seminalis and parts of the uterus were separately dissected out from the individual flukes, and the remaining fluke bodies were frozen at –30°C. The anterior parts were put between 2 slide glasses, fixed in 70% ethanol, stained with Haematoxylin-Carmin solution, and observed for the presence of sperm within the vesicles. Mature eggs were recovered from the uteri and used to observe their development and to be hatched out.

DNA analysis

Total DNA was extracted from individual adult flukes and intrauterine sperm using E.Z.N.A. mollusk DNA kits (Omega Bio-tek, Doraville, USA) and QIAamp DNA micro kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), respectively. DNA fragments of the ITS1 region were amplified, and their DNA types (F. hepatica type, F. gigantica type and heterogeneous types) were analysed based on the nucleotide in the 6 variable sites using direct sequencing (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Kikawa, Sakaguchi, Shimo, Terasaki, Shibahara and Fukuda2005a) and/or the PCR-RFLP method (Ichikawa and Itagaki, Reference Ichikawa and Itagaki2010).

Development of eggs

To clarify the viability and development of the eggs of F1 and F2 generations derived from the parental flukes Fh no. 3 and Fg no. 20, intrauterine eggs were incubated at 28°C for 10 days under no light and then exposed to light at 3-day intervals for a period of 30 days for miracidia to hatch out. The development of eggs was recorded on day 30 after incubation.

RESULTS

Hybridization experiments

Two and 13 out of the 15 parental Fasciola adults recovered from one goat showed PCR-RFLP band patterns (Fig. 1) and sequences identical to those (AB207139, AB207142) of F. hepatica and F. gigantica, respectively, and they were therefore identified as F. hepatica and F. gigantica, respectively. Similarly, 3 and 15 of the 18 parental adults from the other goat were identified as F. hepatica and F. gigantica, respectively. These results confirmed that adult flukes of the two Fasciola species co-existed in the bile ducts of individual goats. All of the adults obtained had many sperm in the seminal vesicles.

Fig. 1. PCR-RFLP band patterns in the ITS1 amplicons of parental adults of Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica recoverd from 1 goat. Lanes 3 and 4 show the band patterns of F. hepatica, and the other lanes show those of F. gigantica.

Spermatozoa observed as cotton-like masses were recovered from uteri of the 30 parental adults except for 2 adults (including Fg no. 23) of F. gigantica and 1 adult (Fh no. 3) of F. hepatica, in which there were no sperm in the uteri. From the results of ITS1 typing by PCR-RFLP and sequencing in the ITS1 region, the sperms obtained from the uteri of 12 (including Fg no. 3) and 9 (including Fg no. 20) parental adults of F. gigantica were identified as F. gigantica and F. hepatica, respectively, and the sperms from 4 parental adults of F. hepatica were all identified as F. hepatica. The other 5 parental adults of F. gigantica were considered to have simultaneously had both sperm of F. hepatica and F. gigantica in their uterus, because ITS1 types of their sperm showed the heterogeneous type of the two Fasciola species. These findings suggested that at least 14 parental adults of F. gigantica had been inseminated with sperm of F. hepatica.

F1 generation

The recovery rates of adults from infected rats were 47·5% (38 adults) in the F1 generation from parental Fh no. 3, 13% (13 adults) in F1 from Fg no. 3, 45% (45 adults) in F1 from Fg no. 20, and 37·5% (30 adults) in F1 from Fg no. 23. All of the F1 adults showed heterogeneous type (AB207147) in the ITS1 sequence, suggesting that they were hybrids F1 between the two Fasciola species.

The 123 adults of F1, except for 3 adults, had many spermatozoa in seminal vesicles, suggesting that they have the ability for spermatogenesis (Figs. 2 and 3). The other 3 F1 adults, of which 2 were derived from Fh no. 3 and 1 from Fg no. 20, contained no or only a few spermatozoa with round rosetted cells in the vesicles, indicating that they have abnormal spermatogenesis (Fig. 3). The ratios of body length and width (BL/BW) of the adults were 2·97±0·54 (mean±s.d.) with a range of 2·2 to 4·5 in F1 derived from Fh no. 3 and 2·48±0·70 (mean±s.d.) with a range of 1·8–4·7 in F1 from Fg no. 20.

Fig. 2. An adult fluke of the hybrid F1 between Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. A scale bar shows 5 mm.

Fig. 3. The seminal vesicles of hybrid F1 adults between Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. The vesicles contain many spermatozoa (1), many round rosetted cells with only a few spermatozoa (2 and 3), and no spermatozoa and rosetted cells (4).

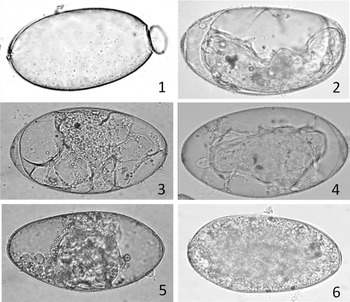

Eggs obtained from the F1 adults could be classified into 4 categories according to their development: category 1 for empty eggs due to hatching out, category 2 for eggs containing an apparently mature miracidium with eyespots, category 3 for eggs containing an embryo of delayed or aberrant development, and category 4 for dead eggs with no development (Fig. 4). Percentages of eggs in the 4 categories are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 4. Egg development of the hybrid F1 between Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica. The eggs were incubated at 28°C for 17 days. (1) The egg classified into category 1 was empty for a miracidium hatching; (2) the egg classified into category 2 contains a well-developed miracidium with eyespots; (3–5) the eggs classified into category 3 contain miracidium forming embryo with delayed or aberrant development; (6) the egg classified into category 4 is dead with no development of egg cell.

Table 1. Development of uterine eggs of the hybrid Fl and F2 adults derived from parental Fh no. 3 and Fg no. 20

* The numbers show average percentages and minimum to maximum percentages in parentheses.

At least 100 eggs were used from each adult worm.

F2 generation

Five (12·5%) and 12 (15%) adults of the F2 generation derived from parental Fh no. 3 and Fg no. 20, respectively, were obtained from rats infected with their metacercariae, and all of the adults showed heterogeneous type (Fh/Fg) in ITS1. Adults of the F2 generation derived from Fh no. 3 had many sperm in the seminal vesicles and showed 2·93±0·19 (mean± s.d.) with a range of 2·83 to 3·03 in BL/BW, and F2 adults from Fg no. 20 had no spermatozoa in the vesicles and showed 2·91±0·38 (mean±s.d.) with a range of 2·37 to 3·48 in BL/BW. Percentages of eggs in the four categories are shown in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Inseminative behaviour of hermaphroditic digeneans includes cross-and self-insemination (Nollen, Reference Nollen1983). Although the inseminative behaviour of Fasciola species remains unclear, Echinostoma caproni conducts self-insemination in parasitization with a single fluke and both cross- and self-insemination with multiple flukes (Nollen, Reference Nollen1990). The present study clarified that F. gigantica carried out interspecific cross-insemination with F. hepatica, since 14 adult flukes of parental F. gigantica obtained from goats in hybridization experiments had the sperm of F. hepatica in their uteri. Moreover, the adults of F. gigantica were thought to actively choose F. hepatica as a partner for mating, since adults of parental F. hepatica recovered were less than one fifth of F. gigantica in number (4 adults of F. hepatica versus 26 of F. gigantica). The adults of F. hepatica might choose another individual of the same species as a partner for mating, although the possibility that they self-inseminated could not be excluded. Digeneans tend to prefer cross-insemination between adults of the same species rather than different species (Nollen, Reference Nollen1996; Cosgrove and Southgate, Reference Cosgrove and Southgate2002). Thus, it is unclear why only F. gigantica mated with F. hepatica and received heterospecific sperm. Although pre-mating isolation and post–mating isolation are known as isolating mechanisms of interspecific hybridization, this study suggests that there is no pre-mating isolation mechanism between F. hepatica and F. gigantica.

A mixture of parental ITS1 sequences in the F1 progeny is convincing evidence for hybridization (Koch et al. Reference Koch, Dobes and Mitchell-Olds2003; Morgan-Richards and Trewick, Reference Morgan-Richards and Trewick2005). The results of ITS1 analysis in the present study suggested that all of the F1 adults derived from the 4 maternal parents (Fh no. 3, Fg no. 3, Fg no. 20, Fg no. 23) were hybrids between F. hepatica and F. gigantica. Although the present results could not confirm the existence of F. hepatica sperm in the uterus of Fg no. 3 (F. gigantica), uterine eggs of Fg no. 3 had certainly been fertilized by sperm of F. hepatica. A possible explanation for this is that the sperm by which mature eggs were fertilized and the sperm found in the uterus were derived from distinct worms. Interspecific hybrid F1 formation in digeneans has been reported in the genera Schistosoma and Echinostoma (Nollen, Reference Nollen1996; Tchuem Tchuente et al. Reference Tchuem Tchuente, Southgate, Jourdane, Kaukas and Vercruysse1997; Morgan et al. Reference Morgan, Dejong, Lwanbo, Mungai, Mkoji and Loker2003; Webster and Southgate, Reference Webster and Southgate2003; Fan and Lin, Reference Fan and Lin2005). Hybrid F1 between 2 species having distinct phenotypes would exhibit mixed phenotypes inherited from parental species, and the hybrid F1 between S. japonicum and S. mansoni, which are different in snail host species, acquired infectivity to both Oncomelania h. chiui and Biomphalaria glabrata (Fan and Lin, Reference Fan and Lin2005). The hybrid F1 between F. hepatica and F. gigantica showed that the recovery rates of adults in rats were 13–47·5%. Published recovery rates of F. hepatica in rats were relatively high, 26·7–27·5% (Thorpe, Reference Thorpe1965) and 24–40% (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Sakamoto, Tsutsumi and Itagaki1994), while those of F. gigantica were remarkably low, 1% (Mango et al. Reference Mango, Mango and Esamal1972) and 0–5% (Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Sakamoto, Tsutsumi and Itagaki1994), suggesting considerable differences in infectivity to rats between the two species. Therefore, the hybrid F1 (e.g. F1 from Fg no. 20) of which the maternal parent was F. gigantica would inherit the capacity of high infectivity to rats from paternal F. hepatica. Furthermore, the present hybrid F1, which showed a wide range of variations in BL/BW (2·2–4·5 for the F1 from Fh no. 3 and 1·8–4·7 for the F1 from Fg no. 20), also should inherit morphological characteristics from both F. hepatica and F. gigantica, since the ratios were low (1·29–2·80) for F. hepatica and high (3·40–6·78) for F. gigantica (Periago et al. Reference Periago, Valero, El Sayed, Ashrafi, El Wakeel, Mohamed, Desquesnes, Curtale and Mas-Coma2007).

Death of egg cells and aberrant development of embryos were observed in the eggs of hybrid F1 and F2 generations, and thus the eggs would experience an extremely low hatching rate. Similar phenomena have also been reported in hybrid offspring between S. mansoni and S. japonicum (Fan and Lin, Reference Fan and Lin2005). In the hybrid progenies between 2 distinct strains of S. intercalatum (Pages et al. Reference Pages, Southgate, Tchuem Tchuente and Jourdane2002) and between 2 strains of E. caproni (Trouve et al. Reference Trouve, Renaud, Durand and Jourdane1998), cercarial and egg production decreased with succession of the hybrid generations. The decreased viability and suitability in hybrid offspring constitute a barrier to gene flow (Byrne and Anderson, Reference Byrne and Anderson1994) and are a post-mating isolation mechanism. Therefore, the present study shows that a post-mating isolation mechanism would appear between F. hepatica and F. gigantica. Nevertheless, the fact that the hybrid F2, as well as F1, matured in final hosts indicates that the isolation mechanism between the two Fasciola species is incomplete.

Most adults of the hybrid F1 experimentally produced in this study are thought to be spermic and to have the ability for normal spermatogenesis because of the presence of many sperm in seminal vesicles. Therefore, the hybrid F1 is completely different in mode of reproduction from aspermic Fasciola forms that occur in Asia and seem to be offspring originating from hybridization between F. hepatica and F. gigantica (Itagaki and Tsutsumi, Reference Itagaki and Tsutsumi1998; Agatsuma et al. Reference Agatsuma, Arakawa, Iwagami, Honzako, Cahyaningsih, Kang and Hong2000; Itagaki et al. Reference Itagaki, Kikawa, Sakaguchi, Shimo, Terasaki, Shibahara and Fukuda2005a,b, 2009, Peng et al. Reference Peng, Ichinomiya, Ohtori, Ichikawa, Shibahara and Itagaki2009) and to reproduce parthenogenically most probably in apomixis. Furthermore, aspermic adults of the hybrid F2 derived from Fg no. 20 would also differ from Asian aspermic Fasciola forms in mode of reproduction, since only a few uterine eggs of the adults developed and hatched out in contrast to Asian aspermic Fasciola sp. showing high hatching rate of eggs (Itagaki et al. unpublished data).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (no. 18405035) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.