Introduction

Hepatozoon species are apicomplexan, blood protozoan parasites distributed worldwide and adapted to a wide variety of vertebrates (Smith, Reference Smith1996). Their complex life cycle is heteroxenous in nature and involves blood-sucking vectors (metastigmatid and mesostigmatid mites, fleas, mosquitoes and lice), in which the sexual cycle occurs with posterior formation of multisporocystic oocysts containing infective sporozoites. Transmission to vertebrate intermediate hosts occurs through the consumption of infected arthropods. After ingestion, the released sporozoites undergo merogony in a variety of organs (lungs, spleen, liver, kidney and skeletal muscle), depending on the vertebrate hosts or the parasite species. Merogony is followed by gamontogony, with the development of gamonts in leucocytes or erythrocytes (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Desser and Martin1994; Ewing and Panciera, Reference Ewing and Panciera2003; Laison et al., Reference Laison, Paperna and Naiff2003; Watkins et al., Reference Watkins, Moshier and Pinter2006; Baneth et al., Reference Baneth, Samish and Shkap2007).

Alternative life cycles of some Hepatozoon spp. can include more than one vertebrate intermediate host, which acts as a paratenic host, harbouring in the tissues an infective quiescent form of the parasite called the cystozoites (Smith, Reference Smith1996). Those cyst forms have been demonstrated in the life cycle of Hepatozoon species that infect anurans, reptiles and mammals (Desser, Reference Desser1990; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Desser and Martin1994; Laison et al., Reference Laison, Paperna and Naiff2003; Viana et al., Reference Viana, Soares, Silva, Paiva and Coutinho2012). In this predator–prey transmission, the vertebrate intermediate hosts become infected through the ingestion of prey containing cystozoite stages of the parasite (Smith, Reference Smith1996; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Little and Ewing2008; Viana et al., Reference Viana, Soares, Silva, Paiva and Coutinho2012).

Hepatozoon spp. infection has been detected in a wide range of wildlife species (Criado-Fornelio et al., Reference Criado-Fornelio, Ruas, Casado, Farias, Soares, Müller, Brum, Berne, Buling-Saraña and Barba-Carretero2006; Metzger et al., Reference Metzger, Paduan, Rubini, Oliveira, Pereira and O'Dwyer2008; André et al., Reference André, Adania, Teixeira, Vargas, Falcade, Sousa, Salles, Allegretti, Felippe and Machado2010; Farkas et al., Reference Farkas, Solymosi, Takács, Ákos, Hornok, Nachum-Biala and Baneth2014), including wild rodents (Duscher et al., Reference Duscher, Leschnik, Fuehrer and Joachim2014; Rigó et al., Reference Rigó, Majoros, Szekeres, Molnár, Jablonszky, Majláthová, Majláth and Foldvári2016; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Aragona, Muñoz-Leal, Pinto, Melo, Braga, Costa, Martins, Marcili, Pacheco, Labruna and Aguiar2016; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017). However, the knowledge about species diversity, distribution, vectors and life cycle in wild rodent populations remains quite limited.

Balfour (Reference Balfour1905) reported a species of haemogregarina (Leucocytozoon muris) infecting the leucocytes of a rodent, Rattus norvegicus, from Sudan (Wenyon, Reference Wenyon1926) for the first time. Miller (Reference Miller1908), in the USA, elucidated the complete life cycle of a haemogregarina from Rattus rattus and named it Hepatozoon perniciosum. Years later, all known species of Leucocytozoon and Haemogregarina from mammals were transferred to the genus Hepatozoon (Wenyon, Reference Wenyon1926), and H. perniciosum was considered to be synonymous with Hepatozoon muris. In São Paulo State, Brazil, Carini (Reference Carini1910) observed H. muris infecting Mus decumanus and Carini and Maciel (Reference Carini and Maciel1915) first reported Hepatozoon sp. in a wild rodent, Akodon fuliginosus, describing it morphologically and considered as a different species, Hepatozoon akodoni (syn. Haemogregarina akodoni).

Since then, no other reports of rodent Hepatozoon species have been made, mainly in Brazil, primarily because most of the new records of Hepatozoon infections in wild rodents are based on molecular features, without incorporating morphological information of the protozoan (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Alvares, Boratynski, Brito, Leite and Harris2014; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Aragona, Muñoz-Leal, Pinto, Melo, Braga, Costa, Martins, Marcili, Pacheco, Labruna and Aguiar2016; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017). Therefore, unidentified Hepatozoon species have been reported in rodent species (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Alvares, Boratynski, Brito, Leite and Harris2014; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Aragona, Muñoz-Leal, Pinto, Melo, Braga, Costa, Martins, Marcili, Pacheco, Labruna and Aguiar2016; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017; Kamani et al., Reference Kamani, Harrus, Nachum-Biala, Gutiérrez, Mumcuoglu and Baneth2018) without being named. Those aspects emphasize the importance of including the description of life cycle stages in addition to molecular tools to describe new species or to re-describe recognized Hepatozoon organisms.

During a previous study, we investigated the possibility of transmission of Hepatozoon canis to dogs by predation of infected rodents, comparing the species found in wild rodents with H. canis detected in dogs from the same region (Demoner et al., Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016). Moreover, a new species of Hepatozoon infecting wild rodents was detected. Herein, we describe a new rodent Hepatozoon species, Hepatozoon milleri sp. nov., based on morphometric, morphological and molecular aspects.

Material and methods

Rodents’ collection and identification

As part of a study on canine hepatozoonosis in order to evaluate the relationships among Hepatozoon spp. infecting wild rodents and domestic dogs (Demoner et al., Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016), rodents were live-trapped in three forest fragments in the municipality of Botucatu, São Paulo State, southeastern Brazil, between November 2013 and June 2014. The animals were collected along terrestrial transects using Sherman and Pitfall traps as previously described (Demoner et al., Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016). In total, 67 rodents were captured and were anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, and blood collection was performed by cardiac puncture for use in genetic and morphological identification. A thin blood smear of each rodent was prepared, fixed with methanol, stained with Wright–Giemsa and screened for Hepatozoon gamonts. All the ectoparasites attached on the rodents were collected and identified.

This study was performed on blood and tissue samples from 11 Akodon montensis, which had their specific identification determined, first by their morphological aspects, especially from the head, and later, confirmed by PCR and sequencing. The sequences obtained from the rodents blood were compared for similarity with the sequences of other rodents available in GenBank (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and presented 99% of similarity with A. montensis from Brazil (GU938933 and KJ013083).

Euthanasia of all collected rodents was performed by deep anaesthesia with isoflurane, followed by organ removal (heart, lung, kidney, spleen, liver, and skeletal cardiac and muscle) (Demoner et al., Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016).

Hepatozoon sp. identification and characterization

These 11 rodents were found to be infected with a different Hepatozoon species by either microscopy or PCR. The parasitaemia was calculated as the percentage of infected leucocytes observed in 200 cells (Aktas et al., Reference Aktas, Özübek, Altay, Balkaya, Utuk, Kırbase, Simsek and Dumanlı2015). Collected tissues were preserved for molecular identification of Hepatozoon spp. and for histological examination. For histological evaluation, formalin-fixed tissue samples were routinely processed and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (Kiernan, Reference Kiernan2015). Parasite morphology was analysed by optical microscopy, at objectives of 40× or 100×, and ocular of 10×. For the morphometric study, a computerized image analysis system was used, and measurements of the length and the width of gamonts and tissue stages were obtained using the software Qwin Lite 2.5 (Leica). In order to characterize the Hepatozoon species, DNA from rodent blood and tissue samples (approximately 100–200 µL of whole blood and 20–50 mg of skeletal muscle, spleen, liver, lung and kidney) was extracted using the Illustra Blood genomic Prep Mini Spin Kit® and the Illustra Tissue Mini Spin Kit® (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Amplification of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene (a 600 bp fragment) of Hepatozoon spp. was performed on the rodent samples using the primer pair HepF300 (5′-GTT-TCT-GAC-CTA-TCA-GCT-TTC-GAC-G-3′) and Hep900 (5′-CAA-ATC-TAA-GAA-TTT-CAC-CTC-TGA-C-3′) (Ujvari et al., Reference Ujvari, Madsen and Olsson2004). In order to amplify a larger segment of the 18S rRNA of Hepatozoon spp. (approximately 1120 bp), a second PCR assay was carried out using the primers 4558 (5′-GCT-AAT-ACA-TGA-GCA-AAA-TCT-CAA-3′) and 2733 (5′-CGG-AAT-TAA-CCA-GAC-AAA-T-3′) (Mathew et al., Reference Mathew, Van Den Bussche, Ewing, Malayer, Latha and Panciera2000), for additional phylogenetic analysis. PCR reaction conditions and sequencing were described before by Demoner et al. (Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016).

To avoid misdiagnosis of Hepatozoon monozoic cysts with Toxoplasma gondii, a PCR was performed on DNA tissues only from the rodents that were positive to monozoic cyst on the tissues’ histology. The PCR was conducted with the primers TOX4 (5′-CGC TGC AGG GAG GAA GAC GAA AGT TG-3′) and TOX5 (5′-CGC TGC AGA CAC AGT GCA TCT GGA TT-3′), which targeted a 529-bp fragment of the T. gondii repeated sequence (Homan et al., Reference Homan, Vercammen, De Braekeleer and Verschueren2000).

By comparing for similarity with the sequences available in GenBank (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), the sequences obtained in the present study were identified as Hepatozoon sp. and were subjected to multiple alignment analyses (with additional Hepatozoon spp. sequences retrieved from Genbank®) using the MUSCLE algorithm in the software Geneious v.7.1.3 (Biomatters, http://www.geneious.com), for phylogenetic analysis. Only the sequences with at least 990 bp overlapping were used for the multiple alignment.

The best evolutionary model for Bayesian inference, based on the Akaike information criterion, was identified using the jModelTest v.2.1.10 (Darriba et al., Reference Darriba, Taboada, Doallo and Posada2012). The chosen parameter of the substitution model was GTR + G. For phylogenetic reconstruction, MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, Reference Ronquist and Huelsenbeck2003) was used to construct the phylogenetic tree by Bayesian inference. Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations were run for 107 generations in two parallel runs, with sampling of trees at 1000-generation intervals and a burn-in of 25%. Phylogenetic trees were visualized in FigTree v.1.4.3 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). An alignment with 1007 bp from one Hepatozoon sp. sequence obtained in this study and seven Hepatozoon sp. sequences, isolated from rodents available on GenBank®, was used to estimate the percentage of nucleotide divergence. This analysis was performed on the MEGA6 software, using the p-distance model (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher, Peterson, Filipski and Kumar2013).

Results

General observations

Previously, Demoner et al. (Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016) collected 67 rodents from five different species and 55.2% were PCR positive for Hepatozoon spp. One of the species was A. montensis, with 19 animals collected and 17 infected (89.5%) (Demoner et al., Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016). For the present study, we used only the 11 rodents, all identified as A. montensis, that presented Hepatozoon stages on blood or tissues (Table 1), and were PCR positive. For the species description, we used only the seven rodents that had gamonts on blood smears. Their parasitaemia varied from 9 to 65.5% (mean of 38.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Hepatozoon milleri positivity, in Akodon montensis’ tissues and blood by both PCR and microscopy

Gam., gamont; Paras., parasitaemia; Histol., histology; Mer., meront; Cyst., cystozoite.

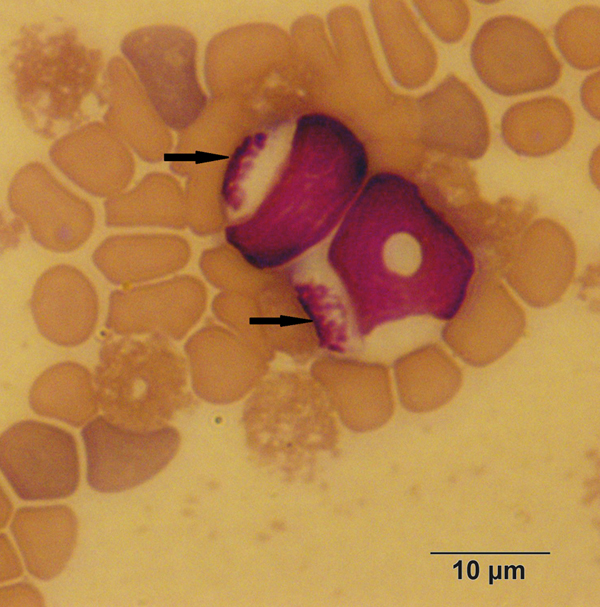

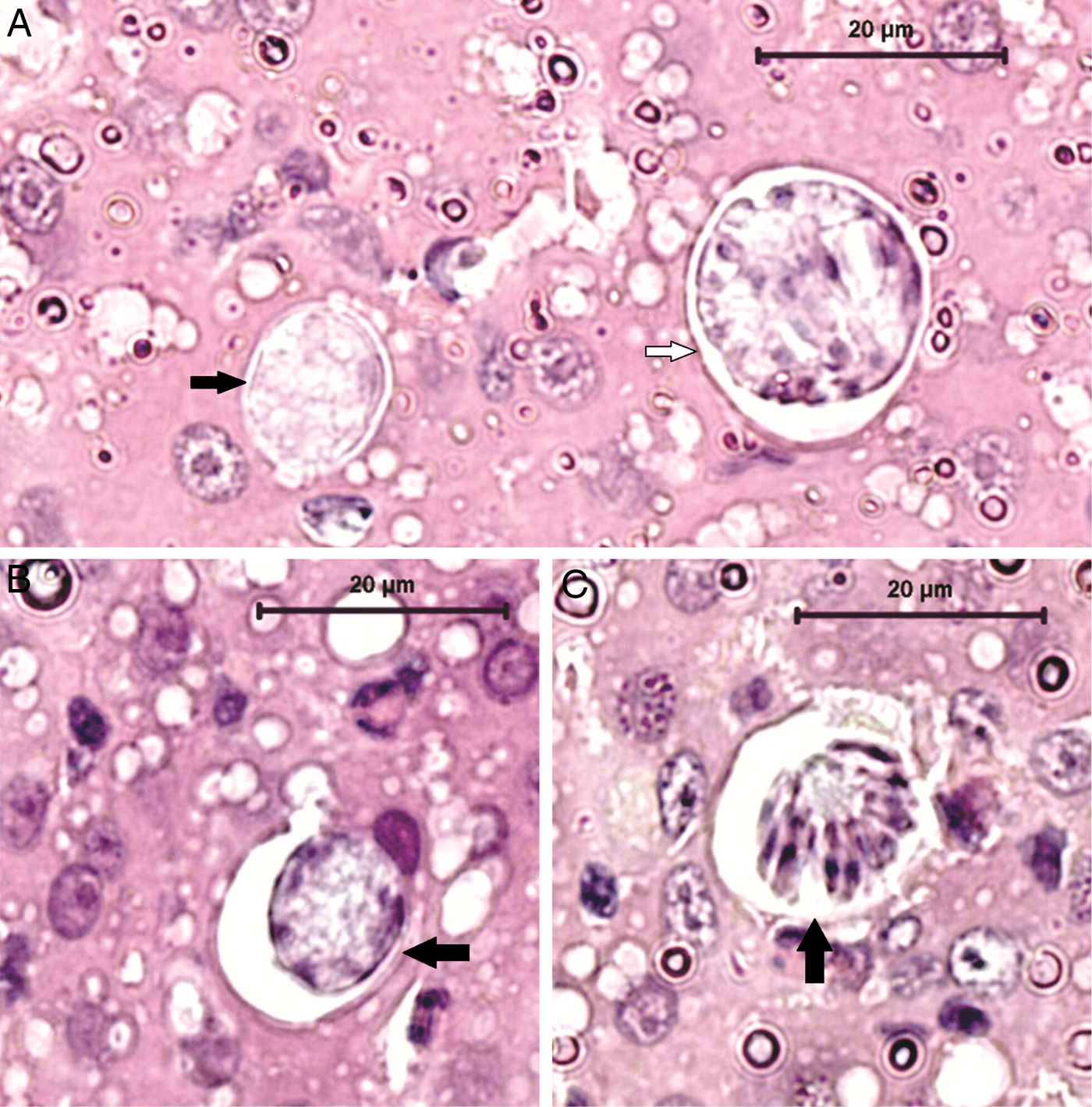

By morphological examination, three different parasite stages were found in the infected rodents: gamonts in the peripheral blood (within mononuclear leucocytes or extracellular/free parasites) (Fig. 1); mature and immature meronts (exclusively in the liver, within hepatocytes) (Fig. 2); and cystozoites (monozoic cysts – cysts with one zoite inside) in the lung, spleen or kidney (Fig. 3) (Table 1). The gamonts were elongated and oval, with the cytoplasm pale blue stained. Its main characteristic was the nucleus that was large, lightly condensed and very granular, occupying almost half of the gamont cytoplasm, centrally located or displaced to one extremity of the gamont. The meronts were in different stages of development. The immature meronts were round-to-oval in shape, containing amorphous material enclosed within a thick wall (Fig. 2A). As it became more developed, a basophilic-stained material was formed at the periphery of the cell, and would originate the merozoites (Fig. 2B). The mature meronts were globular shaped, with a thick membrane enclosing the well-defined and elongated merozoites (with a single nucleus) formed around the residual body, whose number varied from 20 to 30 (Fig. 2C). The cystozoites were ovoid shaped, with the cytoplasm staining white surrounding a single zoite, which was curved and mononuclear (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1. Gamonts of Hepatozoon milleri sp. nov. in the peripheral blood of an Akodon montensis. Giemsa stain.

Fig. 2. Histological detection of Hepatozoon milleri sp. nov. meronts in the liver of an infected Akodon montensis. (A) Two immature meronts, with different developmental stages, containing amorphous material. (B) Further developed meront characterized by basophilic-stained material at the periphery of the cell, which probably gives rise to the merozoites. Haematoxylin and eosin stain, bar = 20 µ m. (C) Mature meront. Note numerous well-defined merozoites arranged around the residual body. Haematoxylin and eosin stain, bar = 20 µ m.

Fig. 3. Cystozoite of Hepatozoon milleri sp. nov. within a monozoic cyst in the spleen of an infected Akodon montensis. Haematoxylin and eosin stain, bar = 20 µ m.

Only two of the 11 infected rodents were infested by a few mesostigmatid mites that were morphologically identified as Androlaelaps rotundus, a non-blood-sucking mite, discarding its role as possible Hepatozoon vector.

Molecular and phylogenetic analysis

The sequences obtained from the 11 PCR-infected animals were all identical, on blood and tissues. Based on the PCR and sequencing, a Hepatozoon sp. sequence, with lengths ranging from 1000 to 1050 base pairs (bp), was obtained from the blood and tissues of infected A. montensis specimens. BLAST analysis of the obtained sequence showed nucleotide sequence similarities (97–99%) with other Hepatozoon sequences detected in wild rodents from various parts of the world [Genbank accession numbers: FJ719817 and FJ719819 (Hepatozoon sp. in Abrothrix olivaceus and Abrothrix sanborni, respectively, from Chile), AB181504 (Hepatozoon sp. in Bandicota indica from Thailand), AY600625 and JX644997 (Hepatozoon sp. detected in bank voles from Europe)].

The phylogenetic tree based on 992 bp from the 18S rRNA fragment indicated that the sequence from the Akodon-derived Hepatozoon, considered as H. milleri sp. nov., grouped into a major clade containing Hepatozoon spp. sequences detected in wild rodents in several regions of the world, while sequences from carnivores, reptiles, amphibians and marsupials formed distinct clades (Fig. 4). The nucleotide divergence among H. milleri sp. nov. and Hepatozoon spp. in rodents around the world ranged from 0.69 to 2.68% (Table 2). The new sequence reported in this study clustered with Hepatozoon sequences previously isolated from wild rodents in Chile (FJ719817; FJ719819) with nucleotide divergence of 0.69 and 0.89%. The p-distance between H. milleri sp. nov. and Hepatozoon spp. from rodents in Brazil were of 0.6% (KP757838), 1.0% (KX776349; KX776353) and 3.7% (KX776335; KX776337). However, the sequences (KP757838; KX776349; KX776353; KX776335; KX776337) were too short (≈600 bp) to be included in the phylogenetic analysis.

Fig. 4. Bayesian inference (BI) tree based on the 18S rRNA gene partial sequences (992 bp) of Hepatozoon milleri sp. nov. isolated from Akodon montensis in south-eastern Brazil and sequences available in the GenBank database, using GTR + G evolutionary model. Babesia vogeli, Cytauxzoon felis, Adelina dimidiata and Adelina grylli were used as outgroups. Numbers at the nodes indicate posterior probabilities under BI. Posterior probabilities lower than 50 are not shown. New sequence identified in the study is indicated in bold.

Table 2. Distance matrix among partial 18S rDNA sequences of Hepatozoon spp. isolated from rodents

Upper triangle shows the number of nucleotide difference, while the lower triangle shows the percentage of nucleotide difference among the sequences.

The tissues of the four animals that presented monozoic cysts in their tissues were PCR negative for T. gondii.

Considering the morphological and molecular features, we described the new Hepatozoon species in A. montensis from Brazil, named H. milleri sp. nov.

Description

Hepatozoon milleri sp. nov.

(Figs 1–3).

Parasite morphology

Gamonts: Elongated with an oval shape, measuring 10.96 ± 0.87 µ m (range 9.42–13.09) long by 4.9 ± 0.51 µ m (3.88–6.38) wide (n = 36). Slightly condensed and granular nucleus, occupying almost half of the cytoplasm, centrally located or displaced to one extremity of the gamont, measuring 5.58 ± 1.02 µ m (3.71–7.13) long by 3.8 ± 0.51 µ m (2.52–4.75) wide (Fig. 1).

Immature meronts: Round-to-oval in shape, containing amorphous material enclosed within a thick wall (Fig. 2A) and measuring 17 ± 3.49 µ m (11.52–25.39) long by 14.43 ± 2.17 µ m (9.83–18.83) wide (n = 42). More developed meronts contained basophilic-stained material at the periphery of the cell, presumed to be merozoite formation (Fig. 2A and B).

Mature meronts: Globular shaped, with a thick membrane enclosing the well-defined and elongated merozoites (with a single nucleus) in numbers of 20–30 (Fig. 2C), formed around the residual body. Meronts measured 20.17 ± 3.26 µ m (15.7–26.94) long by 16.42 ± 2.96 µ m (12.88–21.57) wide (n = 13) and merozoites were 5.63 ± 1.37 µ m (3.11–7.9) long by 1.58 ± 0.27 µ m (1.26–2.06) wide (n = 14).

Cystozoites (monozoic cysts): Ovoid shaped, with the cytoplasm staining white surrounding a single zoite, which is curved and mononuclear (Fig. 3). Cysts measured 5.4 ± 0.82 µ m (4–6.93) long by 1.76 ± 0.28 µ m (1.18–2.58) wide (n = 28).

Taxonomic summary

Phylum Apicomplexa Levine, 1970.

Family Hepatozoidae Wenyon, Reference Wenyon1926.

Genus Hepatozoon Miller, Reference Miller1908.

Type host: Akodon montensis (Rodentia: Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae).

Other hosts: Unknown.

Vector: Unknown.

Type locality: The specimens were captured in forest fragments from the municipality of Botucatu, São Paulo State, southeastern Brazil (22°53′09″S, 48°26′42″W).

Type material: Blood smear and histology slide from Akodon montensis are deposited at INPA (‘The National Institute of Amazonian Research’), Av. André Araújo, 2936 – Petrópolis, Manaus – AM, Brazil, 69067-375. 1x blood smear is deposited under accession number INPA 15a and 1x histology slide is deposited under accession number INPA 15b.

Other material: DNA samples are conserved at the Parasitology Department, IBB, Unesp, São Paulo, Brazil.

DNA sequence: The 18S rRNA gene sequence has been deposited in the Genbank under the accession number KU667308.

ZooBank registration: In accordance with section 8.5 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), details of the new species are submitted to ZooBank with the Life Science Identifier (LSID) urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act: EE4F5009-0860-4D1A-B787-E55FCEAA7C94.

Etymology: The name H. milleri sp. nov. is homage to Dr William Whitfield Miller, who described the genus Hepatozoon as intra-leucocytic haemogregarines in laboratory rats.

Remarks:

The morphometric data of others rodents Hepatozoon species and H. milleri sp. nov. are summarized in Table 3. The gamonts morphometry were similar among the species. In the original description of H. muris (Miller, Reference Miller1908), the gamonts were slightly longer than the H. muris studied by Carini and Maciel (Reference Carini and Maciel1915), and H. milleri from the present study. The morphometry of the gamonts of H. muris described by Miller (Reference Miller1908) was 12 × 6 µ m, whereas the gamonts of the H. muris described by Carini (Reference Carini1910) measured 10–13 µ m × 4–6 µ m. The gamonts of H. akodoni described by Carini and Maciel (Reference Carini and Maciel1915) measured approximately 10 × 3.5 µ m, being smaller than the H. muris gamonts. The gamonts described herein measured 10.9 × 4.9 µ m on average and, despite being smaller than H. muris, are wider than H. akodoni described by Carini and Maciel (Reference Carini and Maciel1915). By contrast, Hepatozoon sp. from Clethrionomys glareolus (syn. Myodes glareolus) (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing, Little and Reichard2007) and H. muris of R. norvegicus (Harikrishnan et al., Reference Harikrishnan, Ponnudurai and Anna2011) were much smaller than the other reported species.

Table 3. Measurements of developmental stages of Hepatozoon milleri sp. nov. and other rodents Hepatozoon

N/A, data not available.

In most of the Hepatozoon species reported, the morphometry of the gamont nucleus was not recorded, but in general, they were ovoid and centrally located, slightly granular. The nucleus of H. milleri was larger than the nucleus of H. akodoni (Carini and Maciel, Reference Carini and Maciel1915) and the one studied by Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing, Little and Reichard2007). The main characteristic of the H. milleri gamont nucleus is its sparsity and large size, occupying half of the gamont cytoplasm. This characteristic was observed in all blood smears from all positive animals. In contrast, the nucleus of H. muris gamonts were central and condensed (Miller, Reference Miller1908). Moreover, the cells parasitized by H. akodoni gamonts had their nucleus morphology changed, becoming more fragmented (Carini and Maciel, Reference Carini and Maciel1915), a characteristic that was not observed in the present study.

Meronts in various stages of maturity were observed in this study. The earliest meronts were similar in size and appearance to immature meronts that have been previously described in small rodents infected with Hepatozoon spp. (Miller, Reference Miller1908; Carini, Reference Carini1910; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing, Little and Reichard2007; Breshears et al., Reference Breshears, Kocan, Johnson and Panciera2009). On the other hand, the morphology and size range of mature meronts, detected in Brazilian wild rodents, are not consistent with previous descriptions of developed meronts in rodents from other regions. For example, Miller (Reference Miller1908) detected larger mature meronts (mean of 25 × 30 µ m, some reaching 28 × 35 µ m) of H. muris in infected laboratory rats, containing a small number of merozoites (12–20), whereas we found meronts, which at maturity measured 20 × 16 µ m on average, containing from 20 to 30 merozoites. The developed meronts of H. muris described by Carini (Reference Carini1910) were smaller (diameter of 15–30 µ m) and enclosed numerous merozoites (25–50). Unfortunately, Carini and Maciel (Reference Carini and Maciel1915) did not observe tissue meronts of H. akodoni in the rodent organs. Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing, Little and Reichard2007) and Breshears et al. (Reference Breshears, Kocan, Johnson and Panciera2009) studied Hepatozoon sp. in Sigmodon hispidus in the USA. The infected wild rodents harboured mature meronts greater (20 × 30 µ m) than those reported in our study and had merozoites radially arranged in numbers of 50 approximately, in contrast to the meronts reported here, which had laterally or radially arranged merozoites.

Cystozoites (monozoic cysts) were detected in the lungs, spleen and kidneys of some Hepatozoon-infected rodents. Laakkonen et al. (Reference Laakkonen, Sukura, Oksanen, Henttonen and Soveri2001) detected monozoic and dizoic cysts of Hepatozoon erhardovae in the lungs of C. glareolus in Europe and cystic forms of Hepatozoon griseisciuri have been recorded in the lungs of the grey squirrel Sciurus carolinensis (Desser, Reference Desser1990). Conversely, Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing, Little and Reichard2007) did not observe cyst formation in tissues from naturally Hepatozoon-infected wild rats from the USA. Among Hepatozoon spp., the cyst form differs mainly in size (10–21 µ m long by 2–17 µ m wide) than it does in morphology, which is typically round-to-oval shaped containing one (monozoic) or two (dizoic) curved mononuclear zoites (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen, Sukura, Oksanen, Henttonen and Soveri2001; Laison et al., Reference Laison, Paperna and Naiff2003; Baneth et al., Reference Baneth, Samish and Shkap2007; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Little and Ewing2008).

Discussion

Based on gamonts morphology, morphological and morphometrical characteristics of the blood and tissue stages and finally, molecular and phylogenetic analyses, the protozoa reported in the present study is a new species, described as H. milleri sp. nov. Although there are several Hepatozoon species reported in rodents, most of them were described many years ago, with some studies dating over 100 years. Additionally, those descriptions were based only on morphology, usually of only one developmental stage, the figures were drawn by hand, and measurements were not standardized. Since the authors did not deposit voucher specimens at that time, it is not possible to study those old Hepatozoon species and compare with ours.

Hepatozoon spp. infections have been reported in a wide variety of vertebrates and are found in several mammalian hosts in Brazil (Criado-Fornelio et al., Reference Criado-Fornelio, Ruas, Casado, Farias, Soares, Müller, Brum, Berne, Buling-Saraña and Barba-Carretero2006; Metzger et al., Reference Metzger, Paduan, Rubini, Oliveira, Pereira and O'Dwyer2008; André et al., Reference André, Adania, Teixeira, Vargas, Falcade, Sousa, Salles, Allegretti, Felippe and Machado2010; Farkas et al., Reference Farkas, Solymosi, Takács, Ákos, Hornok, Nachum-Biala and Baneth2014). However, data on Hepatozoon spp. infecting Brazilian wild rodents are still lacking. The morphological features of the parasite stages suggested that the A. montensis specimens in the present study were infected with a new species of Hepatozoon, whose gamonts have a large and sparse nucleus that occupy half of the gamont cytoplasm, being different from the previously reported species. The possibility that this nucleus characteristic could be the result of nuclear material fragmentation due to an artefact was discarded, as all the smears were done immediately after blood collection, as well as dried and fixed. In addition, we observed the same gamont characteristic in all infected animals.

Balfour (Reference Balfour1905) reported L. muris (syn. H. muris) infecting the R. norvegicus leucocytes (Wenyon, Reference Wenyon1926). A few years later, Miller (Reference Miller1908) elucidated the life cycle of H. muris (H. perniciosum) in laboratory white rats and in its vector, the mite Lelaps echidninus, and observed gamonts formation in lymphocytes of infected rodents (Miller, Reference Miller1908). Remarkable was that H. muris was very pathogenic for the vertebrate host, and that was why Miller (Reference Miller1908), at first, named it H. perniciosum.

With respect to H. muris, the reports from Carini (Reference Carini1910) and from Harikrishnan et al. (Reference Harikrishnan, Ponnudurai and Anna2011) were quite different from the original report (Miller, Reference Miller1908) and may represent different species (Table 3). The gamonts from H. muris described by Miller (Reference Miller1908) were larger (12 × 6 µ m) than the ones from Carini (Reference Carini1910) (10–13 µ m × 4–6 µ m) and Harikrishnan et al. (Reference Harikrishnan, Ponnudurai and Anna2011) (8 µ m). Also, the meronts had different sizes and number of merozoites, being the ones from Miller (Reference Miller1908) larger (25–28 × 30–35 µ m) with a small number of merozoites (12–20), in contrast with those from Carini (Reference Carini1910) which were smaller (15–30 µ m) but with numerous merozoites (25–50). The meronts described by Harikrishnan et al. (Reference Harikrishnan, Ponnudurai and Anna2011) had intermediate size (24–26 × 22 µ m) with no description of the merozoites number.

Developmental stages of H. milleri sp. nov. presented morphological and morphometrical differences from the other reported species. Variations in the tissue tropism of Hepatozoon spp. within the host species are quite common and thereby, influence the location of the tissue merogony (Smith, Reference Smith1996). Histological examination of tissues from Hepatozoon-infected A. montensis revealed Hepatozoon meronts only in the liver. Nevertheless, as we worked with only seven specimens, we cannot assure that merogony occurs exclusively in the liver. Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing, Little and Reichard2007) observed that the merogony of Hepatozoon sp. in S. hispidus and Peromyscus leucopus from North America was limited to the liver. Additionally, H. muris in laboratory white rats (Miller, Reference Miller1908) developed meronts in the liver and Carini (Reference Carini1910) observed meronts of H. muris either in the liver or in the lungs of infected R. norvegicus. Unlike those descriptions, merogony of H. erhardovae reported in C. glareolus from Europe occurred exclusively in the lungs (Laakkonen et al., Reference Laakkonen, Sukura, Oksanen, Henttonen and Soveri2001). Furthermore, the predilection site of tissue merogony of H. griseisciuri infecting the grey squirrel S. carolinensis in the USA was the lungs (Davidson and Calpin, Reference Davidson and Calpin1976). The descriptions of the meronts were scarce.

Extracellular parasites were also detected in the blood smears of the infected rodents in the present study, which is not uncommon because previous studies have demonstrated occasionally free gamonts in infected rodents, probably due to the rupture of host cells (Miller, Reference Miller1908; Carini, Reference Carini1910; Laird, Reference Laird1951; Davidson and Calpin, Reference Davidson and Calpin1976; Rigó et al., Reference Rigó, Majoros, Szekeres, Molnár, Jablonszky, Majláthová, Majláth and Foldvári2016).

Most of the recent reports on Hepatozoon species in wild rodent populations have focused mainly on molecular methods without demonstrating the blood parasite forms (Criado-Fornelio et al., Reference Criado-Fornelio, Ruas, Casado, Farias, Soares, Müller, Brum, Berne, Buling-Saraña and Barba-Carretero2006; Allen et al., Reference Allen, Yabsley, Johnson, Reichard, Panciera, Ewing and Little2011; Maia et al., Reference Maia, Alvares, Boratynski, Brito, Leite and Harris2014; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Aragona, Muñoz-Leal, Pinto, Melo, Braga, Costa, Martins, Marcili, Pacheco, Labruna and Aguiar2016; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017; Kamani et al., Reference Kamani, Harrus, Nachum-Biala, Gutiérrez, Mumcuoglu and Baneth2018). Therefore, gamonts comparison among Hepatozoon spp. infecting mammals from previous studies is difficult.

Molecularly, we identified a novel species of Hepatozoon in the A. montensis specimens. Sequences of Hepatozoon species have been recorded in wild and domestic rodents from Europe (Criado-Fornelio et al., Reference Criado-Fornelio, Ruas, Casado, Farias, Soares, Müller, Brum, Berne, Buling-Saraña and Barba-Carretero2006; Rigó, et al., Reference Rigó, Majoros, Szekeres, Molnár, Jablonszky, Majláthová, Majláth and Foldvári2016), Africa (Maia et al., Reference Maia, Alvares, Boratynski, Brito, Leite and Harris2014; Kamani et al., Reference Kamani, Harrus, Nachum-Biala, Gutiérrez, Mumcuoglu and Baneth2018), North America (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Allen, Panciera, Ewing, Little and Reichard2007) and South America (Merino et al., Reference Merino, Vásquez, Martínez, Celis-Diez, Gutiérrez-Jiménez, Ippi, Sánchez-Monsalvez and De la Puente2009; Demoner et al., Reference Demoner, Magro, da Silva, Antunes, Calabuig and O'Dwyer2016; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Aragona, Muñoz-Leal, Pinto, Melo, Braga, Costa, Martins, Marcili, Pacheco, Labruna and Aguiar2016; Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017).

Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017) have captured 110 wild rodents in southern Pantanal, Brazil, being 77 Thichomys fosteri, 25 Oecomys mamorae and eight Clyomys laticeps. No gamonts were detected in the blood smears, nevertheless, 11 (44%) O. mamorae and 13 T. fosteri (16.9%) were positive for 18SrRNA Hepatozoon spp.-PCR (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017). In contrast, in the present study, the H. milleri parasitaemia was very high, varying from 9 to 65.5% (mean of 38.6%). In relation to the other Hepatozoon sequences from other countries, the nucleotide difference varied from 1.39% with a wild rodent from Thailand (AB181504) and reached 2.68% with the sequence isolated from a squirrel in Spain (EF222259).

The nucleotide divergence among H. milleri sp. nov. and Hepatozoon spp. from rodents in Brazil was of 0.6% (KP757838) and 1.0% (KX776349; KX776353) and among the Chilean rodents was 0.69 and 0.89%, respectively (FJ719817 and FJ719819). These low divergences amidst sequences isolated in rodents from South American demonstrate that these parasites are haplotypes of the species described herein. Nevertheless, since Merino et al. (Reference Merino, Vásquez, Martínez, Celis-Diez, Gutiérrez-Jiménez, Ippi, Sánchez-Monsalvez and De la Puente2009), Wolf et al. (Reference Wolf, Aragona, Muñoz-Leal, Pinto, Melo, Braga, Costa, Martins, Marcili, Pacheco, Labruna and Aguiar2016) and Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017) did not describe the Hepatozoon species, as they had only its molecular data, we decided to describe it providing the morphological data of the parasites.

Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017) observed different Hepatozoon haplotypes and a π value higher through the rodent population than the found amidst other host species; and suggested that there is some degree of Hepatozoon genetic diversity among the population of wild rodents from Brazil. As two of the sequences they have found (KX776335, KX776337) presented a nucleotide divergence of 3.7% in relation to H. milleri sp., they are probably different species.

It has been shown in several studies that differences superior to 1.0% correspond to species-level differences in haemogregarines when the slow-evolving 18S rRNA marker is used (Barta et al., Reference Barta, Ogedengbe, Martin and Smith2012; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Netherlands and Smit2015; Borges-Nojosa et al., Reference Borges-Nojosa, Borges-Leite, Maia, Zanchi-Silva, da Rocha Braga and Harris2017). This was confirmed by Netherlands et al. (Reference Netherlands, Cook, Du Preez, Vanhove, Brendonck and Smit2018) that named three new Hepatozoon species from anurans based on morphological and molecular data, with the new species showing interspecific divergence that varied from 1.0 to 2.0%.

With respect to ectoparasites, Sousa et al. (Reference Sousa, Fernandes, Herrera, Benevenute, Santos, Rocha, Barreto, Macedo, Campos, Martins, de Andrade Pinto, Battesti, Piranda, Cançado, Machado and André2017) in Brazil detected ticks (Amblyomma spp.) and fleas (Polygenis sp.) on rodents, but could not determine if they were infected by Hepatozoon spp. or not. Kamani et al. (Reference Kamani, Harrus, Nachum-Biala, Gutiérrez, Mumcuoglu and Baneth2018), studying Hepatozoon spp. in rodents and their ectoparasites in Nigeria, found two species of ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato and Haemaphysalis leachi), two species of fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis and Ctenophthalmus spp.) and one species of Mesostigmata, gamasid mites (Haemolaelaps spp.), all negative for Hepatozoon spp. DNA. In our study, we did not find ticks infesting the rodents, and unfortunately, we could not identify possible vectors of H. milleri sp. nov. as the only ectoparasites recovered from Hepatozoon-infected rodents were non-haematophagous mites.

In conclusion, in the present study, we described a new Hepatozoon species, H. milleri sp. nov., from wild small rodents in southeastern Brazil. This is the first description of a new Hepatozoon from wild rodent species in Brazil, based on morphological and molecular studies. Further investigation should include the identification of possible vectors, the geographical distribution of the protozoan, as well as the host range, which might clarify some epidemiological aspects of this new parasite.

Author ORCIDs

Lucia Helena O'Dwyer 0000-0002-9367-368X

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to Ana Paula Carmignotto from Federal University of São Carlos (Campus Sorocaba, São Paulo, Brazil) for identifying the rodent species. We are most grateful to Fernando de Castro Jacinavicius from ‘Laboratório Especial de Coleções Zoológicas, Instituto Butantan’, Brazil for identifying the mites.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (Demoner, L.C., FAPESP Proc. No 2012/09715-0 and O'Dwyer, L.H., FAPESP Proc. No 2012/25197-9).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethical Committee for Animal Research at the Instituto de Biociências/UNESP (CEUA – Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais – protocol 431) and under a permanent scientific collection license issued by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) (SISBIO 36283-3).