Introduction

The prevalence of inflammatory non-communicable diseases (IND), for example, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, obesity and asthma, is increasing (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Xu, Xu, Pan, Song, Shan, Zhao and Shan2020; Zwicky et al., Reference Zwicky, Unger and Becher2020), and there are reasons to believe that the control of infectious diseases, including those caused by helminth parasites, influences this epidemiological trend (Bach, Reference Bach2002; Platts-Mills, Reference Platts-Mills2015; Caraballo, Reference Caraballo2018). Although important advances have been made on asthma, especially in detecting risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms initiated by allergens and environmental pollutants, it can be said that improvements in terms of treatment and prevention are needed. In fact, the prevalence of asthma has increased over the past 30 years in almost all countries where it has been investigated, and treatment has not progressed substantially in the past 15 years (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Kleinert and Pavord2015). The advent of biologics, such as monoclonal anti-cytokine antibodies, is increasing, but these products are indicated only for patients with severe asthma, who are no more than 15% of asthmatics (O'Toole et al., Reference O'Toole, Mikulic and Kaminsky2016; Hossny et al., Reference Hossny, Caraballo, Casale, El-Gamal and Rosenwasser2017).

One of the advances on asthma pathogenesis is the increasing understanding of the impairment of the regulatory mechanisms associated with the disease (Roth-Walter et al., Reference Roth-Walter, Adcock, Benito-Villalvilla, Bianchini, Bjermer, Boyman, Caramori, Cari, Chung, Diamant, Eguiluz-Gracia, Knol, Kolios, Levi-Schaffer, Nocentini, Palomares, Redegeld, Van Esch and Stellato2020), which could lead to an overexpression of the type 2 immune response against allergens. Besides, basic and clinical investigations have revealed that helminth infections induce modulation (mainly associated with suppression) of the immune responses. In fact, even though the allergic response and helminth immunity share several characteristics, one of the main differences between them is the role of immunomodulation, which is low in allergy and high during helminthiases. This immunomodulation is elicited by numerous parasite-derived molecules, whose significant anti-inflammatory effects have opened a new hope for IND treatments.

The most frequent soil-transmitted helminth infection is ascariasis, caused by A. lumbricoides (Pullan et al., Reference Pullan, Smith, Jasrasaria and Brooker2014). In highly endemic zones, this disease is thought to produce a state of general immune hyporesponsiveness that impedes the efficacy of viral and bacterial vaccines (Labeaud et al., Reference Labeaud, Malhotra, King, King and King2009; Salgame et al., Reference Salgame, Yap and Gause2013). But more recently, it has been shown that, regarding allergy, ascariasis can exert a dual effect on the host. Heavy intensity infections are associated with a reduction of allergic symptoms, while low parasite burden infections are related to increased allergy symptoms (Caraballo, Reference Caraballo2018; Zakzuk et al., Reference Zakzuk, Casadiego, Mercado, Alvis-Guzman and Caraballo2018). The causes of these two general outcomes are unknown but probably have to do with the level of exposure and host genetic susceptibility (Caraballo, Reference Caraballo2018). However, the mechanisms of Ascaris-induced immunosuppression have been investigated during the last years and several anti-inflammatory products have been isolated and tested, among them the cysteine protease inhibitors, also known as cystatins. In this review, we describe the evolution and findings of the experimental studies on the immunomodulatory properties of helminth-derived cystatins, with special focus on the A. lumbricoides cysteine protease inhibitor (Al-CPI) and its effects on a model of allergic airway inflammation.

The role of immunomodulation in host–parasite relationships

General mechanisms of immunity to A. lumbricoides

The relationships between Ascariasis and asthma have been studied in view of the similarities and differences between the immune mechanisms of both conditions and to better understand allergy and Ascaris immunity. However, the information about the natural immune response to Ascaris lumbricoides is very scarce and most of the analyses are the sum of experimental studies with various helminths, several of them infecting non-natural hosts. For human infection with A. lumbricoides (ascariasis), it has been exceedingly difficult (for various reasons including ethical ones) to define the defence mechanisms, so the information is limited; as a result, it is one of the infections with less coherent information, despite its high prevalence and disease burden. Here we make a brief comment on studies evaluating the immune responses in humans and pigs, an experimental model where natural infection with Ascaris suum resembles ascariasis in humans.

Intestine

According to the life cycle of A. lumbricoides, the intestine is its first meeting place with the defence system. Research on the immune response at this level is scarce and has focused on antibody production, the cellular response and the ability to eliminate the parasite (Geiger et al., Reference Geiger, Massara, Bethony, Soboslay, Carvalho and Correa-Oliveira2002; King et al., Reference King, Kim, Dang, Michael, Drake, Needham, Haque, Bundy and Webster2005). To overcome the limitations of human experimentation, studies have been conducted in pigs infected with A. suum. In these animals, most larvae are eliminated from the intestine between 14 and 21 days (Masure et al., Reference Masure, Wang, Vlaminck, Claerhoudt, Chiers, Van den Broeck, Saunders, Vercruysse and Geldhof2013b). Several investigators have identified mechanisms that might be relevant to humans with ascariasis and the factors that influence the progression or control of the infection (Jungersen et al., Reference Jungersen, Eriksen, Roepstorff, Lind, Meeusen, Rasmussen and Nansen1999; Masure et al., Reference Masure, Wang, Vlaminck, Claerhoudt, Chiers, Van den Broeck, Saunders, Vercruysse and Geldhof2013b). In these and other studies, the role of eosinophils has been investigated using different approaches; for example, in vitro degranulation of eosinophils was elicited by L3 larvae in the presence of serum from pigs immunized with infective A. suum eggs and then challenged with L3 larvae. Interestingly, this effect was abolished when inactivating the serum, suggesting the participation of the complement system and the action of eosinophils in early larval stages (Masure et al., Reference Masure, Vlaminck, Wang, Chiers, Van den Broeck, Vercruysse and Geldhof2013a).

Other studies have attempted to clarify the role of antibodies, revealing a local production of cells secreting IgM and IgA antibodies. IgA is secreted by cells residing in the lamina propria of the proximal jejunum. The highest IgA levels coincided with the larval elimination period (Miquel et al., Reference Miquel, Roepstorff, Bailey and Eriksen2005). Although these immune mechanisms may theoretically lead to total larvae expulsion, sterile immunity is not frequently observed. Elimination of infective eggs and L3 larvae has been found in challenged pigs (Masure et al., Reference Masure, Wang, Vlaminck, Claerhoudt, Chiers, Van den Broeck, Saunders, Vercruysse and Geldhof2013b). Microarray analysis reveals a differential gene program in L4 larvae which makes them more suitable to parasitize the host and evade the immune response (Morimoto et al., Reference Morimoto, Zarlenga, Beard, Alkharouf, Matthews and Urban2003). In summary, the intestine is the main local response site against Ascaris spp., and although the mechanisms are not yet well defined, some experiments suggest that, in addition to the cellular response, especially by eosinophils and intraepithelial T lymphocytes, antibodies could be useful by preventing migration of the parasite and supporting its elimination.

Liver

Most studies evaluating immunity in the liver have been carried out in mice. In humans and pigs, a local immune response has been observed, which does not prevent the migration of the parasite to other organs such as the lung; however, some strains of mice manage to do so, although the mechanisms are unclear (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Behnke, Stafford and Holland2006; Dold et al., Reference Dold, Cassidy, Stafford, Behnke and Holland2010; Deslyper et al., Reference Deslyper, Colgan, Cooper, Holland and Carolan2016). The existence of genetic variants in humans controlling the larval load at different stages of the infection cycle is possible, but this needs to be demonstrated. In studies carried out in pigs, factors other than genetics have been evidenced that could influence the blocking of A. suum migration and the complexity of the lesions at the liver level (Eriksen et al., Reference Eriksen, Andersen, Nielsen, Pedersen and Nielsen1980; Serrano et al., Reference Serrano, Reina, Frontera, Roepstorff and Navarrete2001); however, there is no satisfactory explanation as to why Ascaris is not eliminated in the liver and continues its path to the lung.

Lungs

There is no clear evidence showing a protective effect of the immune response against Ascaris spp. at the pulmonary level; however, as it passes through the lungs, an intense local response has been evidenced that can induce respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnoea, and some severe inflammation like in Loeffler's syndrome (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Behnke, Dold and Holland2013). These symptoms are the product of an inflammatory response induced either by the presence of the larvae and its products locally, remotely or both. Doctors from endemic areas observe that parasitized children present occasional respiratory symptoms, which are supposed to be induced by the migration of the larvae; however, there are no studies that objectively demonstrate this condition, although some have indirectly explored it (Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Isturiz, Sanchez, Perez, Martinez and Castes1992; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Behnke, Stafford and Holland2006) To evaluate the immune response at this level, studies have been designed in both mice and pigs. They have described the local changes that occur with the passage of A. suum through the lungs, suggesting that, of the cell types found, eosinophils play a fundamental role in the elimination of parasites (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Beshah, Nishi, Solano-Aguilar, Morimoto, Zhao, Madden, Ledbetter, Dubey, Shea-Donohue, Lunney and Urban2005; Enobe et al., Reference Enobe, Araujo, Perini, Martins, Macedo and Macedo-Soares2006).

Systemic response

During their entry through the intestinal mucosa and their migration to the liver and lungs, in addition to the local inflammatory response, Ascaris larvae induce immunological changes that can be detected in blood and tissues. These changes include cell mobilization, the production of specific antibodies, the activation of various genes and the production of a wide variety of proteins such as cytokines and chemokines. One of the best known systemic immune changes of ascariasis is the increase of total IgE levels, which is derived, at least in part, from a polyclonal stimulation of B lymphocytes by products of the parasite's body fluid (Lee and Xie, Reference Lee and Xie1995). Eosinophilia is also widely known (Jungersen et al., Reference Jungersen, Eriksen, Roepstorff, Lind, Meeusen, Rasmussen and Nansen1999; Medeiros et al., Reference Medeiros, Silva, Rizzo, Motta, Oliveira and Sarinho2006). There is antibody production both in animals (Lejkina, Reference Lejkina1965) and humans; almost all isotypes and also subclasses of IgG have been detected, although their role in immunity against the parasite is still debated (King et al., Reference King, Kim, Dang, Michael, Drake, Needham, Haque, Bundy and Webster2005) because there is only epidemiological evidence (McSharry et al., Reference McSharry, Xia, Holland and Kennedy1999; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Faulkner, Kamgno, Kennedy, Behnke, Boussinesq and Bradley2005), although, as mentioned, the presence of the immune serum was essential to kill the larvae (Masure et al., Reference Masure, Vlaminck, Wang, Chiers, Van den Broeck, Vercruysse and Geldhof2013a). There is evidence that IgA, both local and serum, could be protective (Miquel et al., Reference Miquel, Roepstorff, Bailey and Eriksen2005). Antibodies are directed against a wide variety of protein antigens detected by WB extracts or purified molecules and also against glycolipids (van Riet et al., Reference van Riet, Wuhrer, Wahyuni, Retra, Deelder, Tielens, van der Kleij and Yazdanbakhsh2006).

Cytokine measurement suggests that in children with ascariasis, there is a strong polarization towards a Th2 profile measured by stimulation with various larval stages of the parasite (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Chico, Sandoval, Espinel, Guevara, Kennedy, Urban, Griffin and Nutman2000). This response appears to increase after repeated treatment with albendazole (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Moncayo, Guadalupe, Benitez, Vaca, Chico and Griffin2008), which could be the result of low parasite burden reinfections that reverse the immunomodulation induced by chronic infections. In utero sensitization against Ascaris-specific antigens has been observed studying the cellular response of the umbilical cord in children born to infected mothers (Guadalupe et al., Reference Guadalupe, Mitre, Benitez, Chico, Nutman and Cooper2009). An interesting aspect of the immune response against Ascaris, as with other helminths, is its ability to completely eliminate parasites and establish permanent immunity (Bourke et al., Reference Bourke, Maizels and Mutapi2011). The complete elimination of parasites in natural hosts is not commonly seen, probably because a protective and immunomodulatory response is established that does not eradicate the parasite but limits its reproduction and damaging effects (Zakzuk et al., Reference Zakzuk, Casadiego, Mercado, Alvis-Guzman and Caraballo2018). According to genetic considerations, it is theoretically possible for one group of the population to undergo a self-cure process and another group to be intensely infected (Caraballo, Reference Caraballo and Holland2013).

Evolution of parasitic immunomodulation studies

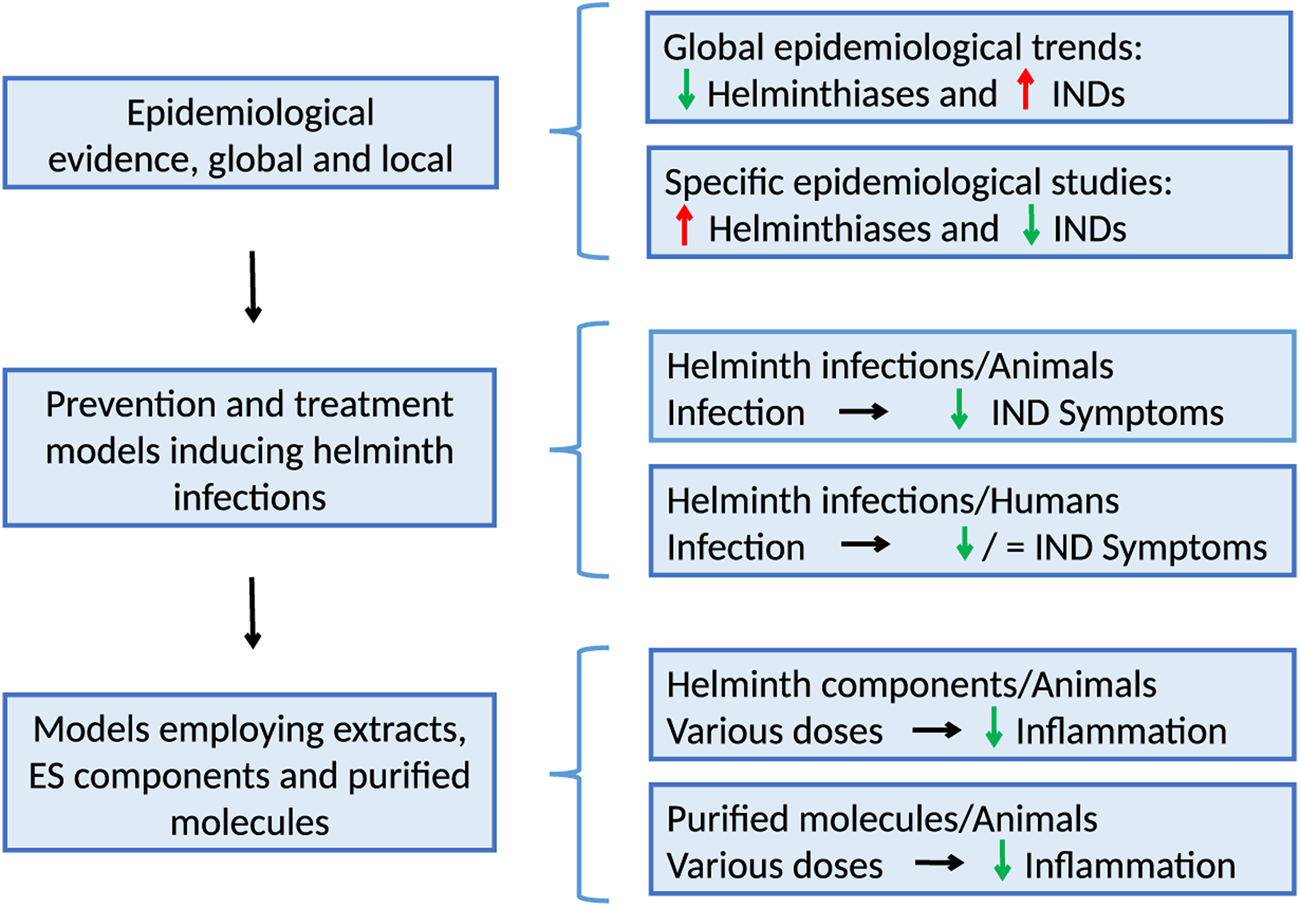

The immunomodulation by parasites was first proposed by Greenwood to explain the low prevalence of autoimmune diseases in Nigeria (Greenwood, Reference Greenwood1968) and then by Gerrard et al. to explain the higher frequency of asthma, eczema and urticaria in the white compared to the Metis populations in Canada (Gerrard et al., Reference Gerrard, Geddes, Reggin, Gerrard and Horne1976). These observations have been followed by a great number of epidemiological studies demonstrating the beneficial effects of different helminthiases on IND, for example, the inflammatory bowel disease and asthma (Maizels, Reference Maizels2016). Also, the possibility that the increasing trends of the prevalence of allergic diseases are related to the parasitic infection control has been considered (Platts-Mills, Reference Platts-Mills2015; Caraballo, Reference Caraballo2018). At the experimental level, several animal models employing a variety of compounds, sometimes purified, have been used (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Barrios, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Franco, Ocampo and Caraballo2017). More recently, ex vivo experiments have been particularly useful for analysing the cellular and molecular effects of recombinant immunomodulators (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Benedetti, Angelina, Palomares and Caraballo2019). The evolution of research on helminth-derived immunomodulators is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The evolution of research on helminth immunomodulation includes epidemiological observations at the local and general levels, case–control studies, treatment trials using helminths, mechanisms of action in animal experimentation and ex vivo assays. IND, inflammatory non-communicable disease.

General mechanisms of helminth immunomodulation

Helminth infections induce species-specific and other more generalized immune responses that may be critical for disease control, but also induce immunomodulation. Two of the most important immunomodulatory effects are systemic activation of type-2 immune responses and immunosuppression. Advances in helminth genomics, proteomics and other systematic biology disciplines have uncovered a wide number of molecules with the potential to modulate host defence and bystander immune responses. Besides proteins, the repertoire of immunomodulatory products derived from helminth includes lipids (Giera et al., Reference Giera, Kaisar, Derks, Steenvoorden, Kruize, Hokke, Yazdanbakhsh and Everts2018) and glycans (Maizels et al., Reference Maizels, Smits and McSorley2018) that activate innate immune responses and play a significant role in immunomodulation. Also, the list of allergenic proteins is growing, and different animal models have shown that they could exert tissue damage through type-2 immune mechanisms and innate immune pathways. The vast number of mechanisms which are relevant in helminth innate immune responses include complement system (Giacomin et al., Reference Giacomin, Gordon, Botto, Daha, Sanderson, Taylor and Dent2008), mucosal barrier (Gerbe et al., Reference Gerbe, Sidot, Smyth, Ohmoto, Matsumoto, Dardalhon, Cesses, Garnier, Pouzolles, Brulin, Bruschi, Harcus, Zimmermann, Taylor, Maizels and Jay2016), neuroimmune networks (Cardoso et al., Reference Cardoso, Chesne, Ribeiro, Garcia-Cassani, Carvalho, Bouchery, Shah, Barbosa-Morais, Harris and Veiga-Fernandes2017), ILC2 (Herbert et al., Reference Herbert, Douglas and Zullo2019) and more classically described granulocyte-mediated mechanisms (Masure et al., Reference Masure, Vlaminck, Wang, Chiers, Van den Broeck, Vercruysse and Geldhof2013a). Also, the role of antigen-presenting cells on immunomodulation is well-studied, even though not well-defined. Induction of tolerogenic APCs has also been linked to helminth immunomodulation; these cells are characterized by predominant IL-10 production and surface expression of ligands of molecules expressed in T cells that may modulate its activity. Other mechanisms include sequestration of adaptor molecules leading to suppression of pivotal innate immune networks: omega-1 is a ribonuclease that targets the global pool of RNA and in this way suppress DC activation through inhibition of CD86 and MHCII expression (Everts et al., Reference Everts, Hussaarts, Driessen, Meevissen, Schramm, van der Ham, van der Hoeven, Scholzen, Burgdorf, Mohrs, Pearce, Hokke, Haas, Smits and Yazdanbakhsh2012). By means of different models of helminth infections, it has been described that specialized innate cells drive type 2 immune polarization. In dendritic cells, parasite products may reduce co-stimulatory molecules and MHC expression which inhibit T-cell activation.

Molecular and genetic aspects of A. lumbricoides cystatins

Structure and biologic function of cystatins

Cystatins are a superfamily of cysteine protease inhibitors that commonly occur as single-domain proteins and mainly inhibit peptidases from the papain (C1) and legumain (C13) families (Turk and Bode, Reference Turk and Bode1991). They were annotated to the gene ontology term ‘cysteine-type endopeptidase inhibitor activity’ (GO 0004869:); by definition: ‘stops, prevents or reduces the activity of a cysteine-type endopeptidase, any enzyme that hydrolyses peptide bonds in polypeptides by a mechanism in which the sulfhydryl group of a cysteine residue at the active centre acts as a nucleophile’ (geneontology.org). Cystatins bind tightly and reversibly to cysteine proteases inhibiting their activities, thus preventing, or controlling protein degradation (Rawlings et al., Reference Rawlings, Tolle and Barrett2004). They are ubiquitously found in most organisms and share a highly conserved motif of five amino acids (Gln-x-Val-x-Gly) in the central part of their sequences as well as an α helix cradled in a sheet of five antiparallel β strands in the tertiary structure (Kordis and Turk, Reference Kordis and Turk2009). Other secreted extracellular proteins such as kininogen, histidine-rich glycoproteins and fetuins also contain cystatin domains and play several functions in addition to inhibiting endogenous thiol proteinases (Turk et al., Reference Turk, Stoka and Turk2008; Shamsi and Bano, Reference Shamsi and Bano2017).

The inhibitory mechanism of cystatins relies on the binding to the active site of a protease by a ‘tripartite wedge’. This consists of a wedge-shaped group of mostly hydrophobic residues that lie at one edge of the β-sheet but arise from three regions on the protein sequence, namely the flexible N-terminus and the two loops between the β-strands. The conserved motif Q-x-V-x-G (where x is usually a small amino acid such as alanine or serine) is in a tight turn between β-strands two and three. The hydrogen-bond ladder between strands two and three extends all the way to the valine in the loop, which forms a hydrogen bond with the glycine. This holds the valine in an unusually strained conformation that enables cystatin to fit into the active site of cysteine proteases and may also help prevent the inhibitor from becoming a substrate of those proteases. Once these residues insert into the active-site groove of the protease, they block access to substrate proteins; the shape of this wedge is complementary to that of the groove, which contributes to the tight binding. Two cystatin molecules can also do ‘domain swapping’ resulting in higher stability or for some vertebrate cystatins allows their oligomerization (Amin et al., Reference Amin, Khan and Bano2020).

Members of the cystatin superfamily are structurally and functionally related, and according to the Pfam annotation (PF00031, https://pfam.xfam.org/family/Cystatin), members of this family can be classified into four types that consider their structural and functional relationships, cellular location and polypeptide features, as follows:

Type 1 or stefins: These are mainly intracellular cystatins but may also appear in body fluids. They are single-chain polypeptides of about 100 residues, without disulphide bonds nor carbohydrate side chains, and with a molecular weight of about 11 kilodaltons (kDa). Stefins inhibit peptidases of the C1 family, for instance lysosomal cathepsins.

Type 2 cystatins: These are extracellular secreted polypeptides largely acidic and synthesized with a 19–28 residue signal peptide. They are about 120 amino acids long, contain conserved cysteine residues that form disulphide bonds and can be glycosylated or phosphorylated. Type 2 cystatins are broadly distributed and found in most body fluids where they inhibit proteases found in the extracellular space, mainly of the C1 family and legumain.

Type 3 or kinin precursor proteins (kininogens): These proteins contain multiple cystatin domains in the same polypeptide chain. In mammals, there are three different types of kininogens: H- (high molecular mass), L- (low molecular mass) kininogen and T-kininogen that is only found in rat. Kininogens ubiquitously exist in vertebrates, including mammals, birds, amphibians and fishes. They vary extremely in both structure and function among different taxa of animals and typically contain a bradykinin domain and one cystatin domain in lampreys, two cystatin domains in fishes or three in mammals, birds and amphibians (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Bongcam-Rudloff, Sollner, Jahnen-Dechent and Claesson-Welsh2009). Kininogens can inhibit calpain and peptidases in families S8 and M12.

Unclassified cystatins: Also designated cystatin-like proteins, this family includes secreted cystatin-like proteins without inhibitory activity such as fetuins and histidine-rich proteins, restricted to vertebrates and phytocystatins from plants. Fetuins can be classified as fetuin-A and fetuin-B and are characterized by the presence of two N-terminally located cystatin-like repeats and a unique C-terminal domain that is not present in other proteins of the cystatin family.

A more recent classification of cystatins has been proposed in the MEROPS database (Rawlings and Bateman, Reference Rawlings and Bateman2021) naming cystatins with the letter ‘I’ for inhibitor and the number 25 (I25), followed by ‘A’ for type 1 stefins (I25A), ‘B’ for type 2 cystatins (I25B) and ‘C’ for type 3 kininogens (I25C). For more information, visit (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops/cgi-bin/famsum?family=I25). Although these classifications are in most cases very useful, for some cystatins can be difficult to apply because there are combinations of different features that may not be attributed to one or other family (Ilgova et al., Reference Ilgova, Jedlickova, Dvorakova, Benovics, Mikes, Janda, Vorel, Roudnicky, Potesil, Zdrahal, Gelnar and Kasny2017), or multidomain cystatins that albeit of high molecular weight (170 kDa), tandem cystatin repeats and degenerated core motifs still resemble type 2 cystatins (Geadkaew et al., Reference Geadkaew, Kosa, Siricoon, Grams and Grams2014).

Genomics of cystatins

The MEROPS database (Rawlings et al., Reference Rawlings, Waller, Barrett and Bateman2014) reports at least 4301 cystatin sequences (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops/inhibitors/) and the SMART database reports at least 9885 cystatin-like domains in 7379 proteins (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/smart/SM00043/). The taxonomic distribution of proteins containing cystatin-like domain (s) is presented in Fig. 2a. Despite their structural diversity, most can inhibit proteinases indicating the conservation of this function. Most cystatins are found in metazoan (76.5%) and viridiplantae (21%) (Fig. 2a). Phylogenomic analysis of the cystatin superfamily tracked their origin prior to the divergence of the major eukaryotic lineages. The progenitor of this superfamily was most probably intracellular and lacked a signal peptide and disulphide bridges. Cystatin from Giardia resembles the most ancestral eukaryotic cystatin (Kordis and Turk, Reference Kordis and Turk2009). A primordial gene duplication produced two ancestral eukaryotic lineages, stefins and cystatins (Muller-Esterl et al., Reference Muller-Esterl, Fritz, Kellermann, Lottspeich, Machleidt and Turk1985). Stefins (Pfam:PF00031) remain encoded by a single or a small number of genes in eukaryotes, whereas cystatins have undergone a more complex and dynamic evolution through numerous gene and domain duplications. In some multicellular eukaryotes, three major bursts of functional diversification have occurred: one in land plants (angiosperms), the second during the evolution of the vertebrates and a third in the ancestor of placental mammals (Margis et al., Reference Margis, Reis and Villeret1998). In plants, cystatins formed a distinct branch called phytocystatins. In vertebrates, there are at least 4360 cystatin-domain-containing proteins with a mutation rate that is faster than in other groups of proteins (Rawlings and Barrett, Reference Rawlings and Barrett1990). Some taxonomic groups such as Fungi, Kinetoplastida and Apicomplexa have lost stefins and cystatins (Kordis and Turk, Reference Kordis and Turk2009).

Fig. 2. (a) Taxonomic distribution of cystatin-domain containing proteins based on the SMART database (SM00043, accessed November 2020), the size on the stacked bar represents the percentage of proteins with the cystatin domain in each taxonomic node. (b) Cladogram of a phylogenetic neighbour-joining tree without distance corrections based on the sequences of type 2 cystatins in parasitic nematodes.

After the analysis of several genomes, it has been established that within metazoan, the highest frequency of cystatins is found in the phylum Chordata (60%), followed by the phyla Arthropoda (12%), Nematoda (3.43%) and Platyhelminthes (0.5%) (Fig. 2a). It seems that the frequency of cystatins in the last three phyla could relate to promoting parasitism and immunomodulation. Indeed, several cystatins have been characterized in parasitic organisms (Klotz et al., Reference Klotz, Ziegler, Danilowicz-Luebert and Hartmann2011a). Cystatins in the salivary glands of ticks are thought to help bypassing the immune response, especially in hard ticks that require to attach to a host for long-term feeding; examples of these arthropod cystatins include syalocystatins, iristatin and Hisc-1 from ixodid ticks (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Kotal, Bensaoud, Chmelar and Kotsyfakis2020). Moreover, transcriptional analysis in Strongyloides ssp. have found that genes encoding cystatins are relevant for parasitism since they are upregulated in parasitic females compared with free-living females (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Tsai, Selkirk and Viney2017).

There are at least 1161 genes coding for cystatin-domain-containing proteins in the phylum Nematoda annotated in the genomes from WormBase Parasite (v15.0). In parasitic nematodes, most characterized cystatins are type 2, although there are also type 1, and others with multidomains. Nematode type 2 cystatins are found in parasitic organisms, including onchocystatin from Onchocerca volvulus, Av-cystatin from Acantocheilonema vitae, Bm-CPI-1 and Bm-CPI-2 from Brugia malayi, Al-CPI from A. lumbricoides and nippocystatin from Nippostrongilus brasiliensis. They are also found in free-living organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans (Fig. 2b). Cystatins regulate physiological processes such as larval moulting and play a critical role as immunomodulators in host–parasite interactions by inhibiting cathepsins, antigen processing and presentation, the expression of pattern recognition receptors and modulating cytokines and nitric oxide production (Khatri et al., Reference Khatri, Chauhan and Kalyanasundaram2020). Some of these immunomodulatory properties have been also described for cystatins in the Platyhelminthes Fasciola hepatica and Schistosoma spp.; although comparative analysis revealed particular structural features in cystatins from cestodes (Guo, Reference Guo2015). In the following section, we describe the biological features of cystatins in the human parasitic nematode A. lumbricoides.

Ascaris lumbricoides cystatins

The MEROPS database reports at least 243 protease inhibitors (known and/or putative) in A. lumbricoides including four cystatins (family IH, clan I25). They are encoded by the genes ALUE_0000175801, ALUE_0002323401, ALUE_0001430001 and ALUE_0001868501 and predicted to be translated in the A. lumbricoides proteome to cystatins of 69, 107, 131 and 138 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 3a.) (UP000036681, TrEMBL, https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000036681). The 69 amino acids cystatin was found to be encoded by a transcript of 237 bp and a single exon; while the 107 amino acids cystatin is encoded by a transcript of 351 bp in three exons, both having 13 homologues in the Onchocercidae family. On the other hand, the 138 amino acids cystatin is encoded by a transcript of 417 bp and four exons, with 169 orthologues within several nematode families including cpi-2 from C. elegans. These transcripts suggest that A. lumbricoides has at least four cystatins, with and without signal peptide, with different lengths and amino acids substitutions (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. (a) Transcript structure of four cystatins in A. lumbricoides (genome PRJEB4950, assembly Ecuador_v1_5_4) encoding the 69 amino acids (aa), 107 aa, 131 aa (Al-CPI) and 138 aa, respectively. (b) Annotation of the protein domains and features in the transcript ALUE_0001430001-mRNA-1 encoding the experimentally verified A. lumbricoides cystatin (Al-CPI).

An experimentally verified cystatin of A. lumbricoides, denominated cpi or Al-CPI, is encoded in the forward strand of the ALUE_0001430001 gene (WormBase https://parasite.wormbase.org) and spans in four coding exons transcribed to 523 base pairs (bp) (ALUE_0001430001-mRNA-1) (Fig. 3b). This gene is translated to the A. lumbricoides cystatin (E9N3T6), which has 131 amino acids and a molecular weight of 14.2 kDa. It has a signal peptide (a.a. 1–20) and a cystatin domain between amino acids 23 and 131 (Fig. 3b). This cystatin also has two disulphide bonds (a.a. 88–98) and (a.a. 109–129) and the biochemical features of a type 2 cystatin. Mei et al. determined the crystal structure of this cystatin to 2.1 Å resolution (PDB 4it7) (Mei et al., Reference Mei, Dong, Li, Liu, Liu, Sun, Liu, Su and Liu2014) and demonstrated that Al-CPI strongly inhibited the activities of cathepsin L, C, S and, in a lower level, of on cathepsin B. Two segments of Al-CPI loops 1 and 2 were proposed as the key structural motifs responsible for Al-CPI binding to proteases and its inhibitory activity. Comparative sequence analysis revealed that Al-CPI has 29 orthologues including two homologues in the pig roundworm (92% identity with the cystatin from A. suum: A. suum: F1LHQ3), two homologues in Parascaris ssp. (85% identity with the cystatin of Parascaris univalens) and 71.5% identity with the cystatin of Toxocara canis (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, the amino acid identity of Al-CPI with the cystatin Ani s 4 from the fish-infecting nematode Anisakis simplex and type 2 cystatins in free-living species such as Caenorhabditis ssp., drops to 40%. Al-CPI also has sequence homology ranging from 48 to 33% with the other three sequences annotated as cystatin-domain-containing proteins in the A. lumbricoides genome (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 4. Gene tree views of the four A. lumbricoides cystatins. (a) The 69 aa (ALUE_0000175801) and 107 aa (ALUE_0002323401) cystatins. (b) The experimentally validated A. lumbricoides cystatin (Al-CPI). (c) The 138 aa cystatin (ALUE_0001868501) which is the orthologue of cpi-2 from the free-living nematode C. elegans.

Fig. 5. (a) Multiple sequence alignment of four A. lumbricoides cystatins. (b) Gene expression profile of cystatins in Ascaris suum based on public RNAseq data from experiments SRP005511 (left), SRP013609 (middle) and SRP010159 (left) showing RNA expression levels in transcripts per million (TPK) in different tissues and lifecycle stages (data from public RNAseq studies downloaded from parasite.wormbase.org). The cystatin annotated as AgR030_g085 in A. suum is the equivalent of Al-CPI in A. lumbricoides.

Data on expression profiles of A. lumbricoides cystatins at the transcriptional or protein levels are extremely limited. However, at least five homologous cystatins are annotated in the A. suum genome with available RNAseq data in different tissues and lifecycle stages (Jex et al., Reference Jex, Liu, Li, Young, Hall, Li, Yang, Zeng, Xu, Xiong, Chen, Wu, Zhang, Fang, Kang, Anderson, Harris, Campbell, Vlaminck, Wang, Cantacessi, Schwarz, Ranganathan, Geldhof, Nejsum, Sternberg, Yang, Wang, Wang and Gasser2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Czech, Crunk, Wallace, Mitreva, Hannon and Davis2011; Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Jasmer and Mitreva2014). We extracted the data on cystatin levels and the results suggest remarkable differences in cystatin mRNA expression between different A. suum tissues (e.g. embryo vs testis) or stages (Fig. 5b). In addition, a proteomic analysis of A. suum fluid compartments and secretory products confirmed the presence of CPI-2a cystatin-like inhibitors in the perienteric and uterine fluids of the adult worm (Chehayeb et al., Reference Chehayeb, Robertson, Martin and Geary2014). Cystatins have been also detected in extracellular vesicles and secretion/excretion body fluids from A. suum (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Fromm, Andersen, Marcilla, Andersen, Borup, Williams, Jex, Gasser, Young, Hall, Stensballe, Ovchinnikov, Yan, Fredholm, Thamsborg and Nejsum2019). Detailed transcriptome and proteomic analyses of A. lumbricoides are needed to verify these results and the relationship between cystatin expression during the different lifecycle stages, as well as specific effects of cystatin variants during host–parasite interactions.

Ascaris lumbricoides-induced immunomodulation

General aspects of the immunomodulation induced by A. lumbricoides

The mechanisms of helminth immunomodulation vary with the species, and some of them have been extensively studied (Homan and Bremel, Reference Homan and Bremel2018; Zakeri et al., Reference Zakeri, Hansen, Andersen, Williams and Nejsum2018; de Ruiter et al., Reference de Ruiter, Jochems, Tahapary, Stam, Konig, van Unen, Laban, Hollt, Mbow, Lelieveldt, Koning, Sartono, Smit, Supali and Yazdanbakhsh2020; Wiedemann and Voehringer, Reference Wiedemann and Voehringer2020); however, basic research on the mechanisms of Ascaris-induced immunomodulation is limited. Ascaris spp. are able to downregulate the immune responses of hosts (Barriga, Reference Barriga1984; Faquim-Mauro and Macedo, Reference Faquim-Mauro and Macedo1998; Caraballo et al., Reference Caraballo, Acevedo and Zakzuk2019), which explains why they are among the most successful parasites. This has been shown in humans and experimental animals, using various strategies. For example, different patterns of cytokine production have been detected among young adults living in an A. lumbricoides endemic area. Chronically infected Ascaris and Trichuris patients with high parasite load presented reduced PBMC reactivity and lower type 1 cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-12, than those non-infected endemic controls (Geiger et al., Reference Geiger, Massara, Bethony, Soboslay, Carvalho and Correa-Oliveira2002). This immune hypo-responsiveness has been associated with greater frequencies of the spontaneous production of IL-10 (Figueiredo et al., Reference Figueiredo, Barreto, Rodrigues, Cooper, Silva, Amorim and Alcantara-Neves2010) and modified Th2-like immune phenotype (Reina Ortiz et al., Reference Reina Ortiz, Schreiber, Benitez, Broncano, Chico, Vaca, Alexander, Lewis, Dougan and Cooper2011) that can impair the immune response to co-infecting parasites (Hagel et al., Reference Hagel, Cabrera, Puccio, Santaella, Buvat, Infante, Zabala, Cordero and Di Prisco2011) and the normal response to vaccines (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Chico, Sandoval, Espinel, Guevara, Levine, Griffin and Nutman2001).

Whether Ascaris-induced immune hyporesponsiveness has an impact on preventing asthma or other allergic diseases remains to be defined, but recent reports show that soil-transmitted helminthiases during childhood protect from wheezing and asthma but not from allergen sensitization (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Chico, Vaca, Sandoval, Loor, Amorim, Rodrigues, Barreto and Strachan2017; Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Versteeg, Wiria, Wammes, Wahyuni, Supali, Sartono, van Ree and Yazdanbakhsh2017). Since Ascaris and other helminths co-infection is very frequent, it is difficult to evaluate their individual downregulatory properties in humans; however, progress on the molecular characterization of parasite immunomodulatory components is expected to facilitate this research.

The mechanisms of the immune downregulatory effects of A. suum infection have been recently explored in a mouse model of LPS-induced inflammatory response (Titz et al., Reference Titz, de Araujo, Enobe, Rigato, Oshiro and de Macedo-Soares2017), finding that infection suppressed secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6) and induces high levels of IL-10 and TGF-β, as well as CD4 + CD25high, Foxp3 + T cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes. This has also been investigated in pigs using transcriptomic analysis, showing that chronic A. suum infection induces suppression of inflammatory pathways in the intestinal mucosa, downregulating genes encoding cytokines and antigen-processing and co-stimulatory molecules. This effect was reproduced by A. suum body fluid in human dendritic cells in vitro (Midttun et al., Reference Midttun, Acevedo, Skallerup, Almeida, Skovgaard, Andresen, Skov, Caraballo, van Die, Jorgensen, Fredholm, Thamsborg, Nejsum and Williams2018).

The immunomodulatory capacity of A. suum and A. lumbricoides components has also been studied in animal models (Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Leite, Pompeu, Cunha, Verri, Soares, Castro and Cunha2008; Dowling et al., Reference Dowling, Noone, Adams, Vukman, Molloy, Forde, Asaolu and O'Neill2011; Almeida et al., Reference Almeida, Nejsum and Williams2018) and some immunomodulatory components found in excretory/secretory products of Ascaris have been identified. Among them, phosphorylcholine-containing glycosphingolipids (Deehan et al., Reference Deehan, Goodridge, Blair, Lochnit, Dennis, Geyer, Harnett and Harnett2002; Kean et al., Reference Kean, Ohtsuka, Sato, Hada, Takeda, Lochnit, Geyer, Harnett and Harnett2006) and PAS-1 (Itami et al., Reference Itami, Oshiro, Araujo, Perini, Martins, Macedo and Macedo-Soares2005; Antunes et al., Reference Antunes, Titz, Batista, Marques-Porto, Oliveira, Alves de Araujo and Macedo-Soares2015) have been more analysed; however, according to the A. suum genome (Jex et al., Reference Jex, Liu, Li, Young, Hall, Li, Yang, Zeng, Xu, Xiong, Chen, Wu, Zhang, Fang, Kang, Anderson, Harris, Campbell, Vlaminck, Wang, Cantacessi, Schwarz, Ranganathan, Geldhof, Nejsum, Sternberg, Yang, Wang, Wang and Gasser2011), this genus might have more than 15 potential immunomodulators. In this regard, the recent analysis of the anti-inflammatory properties of A. lumbricoides cystatin (Al-CPI) (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Barrios, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Franco, Ocampo and Caraballo2017) started a new stage of research on the immunosuppressive potential of this nematode.

Immunomodulation by A. lumbricoides cystatin

Helminth cystatins are secreted during different developmental stages and participate in various physiological processes. As mentioned, they are classified into three classes, in which type-2 members are the ones linked to immunosuppression in mammals. According to the characterization of diverse cystatins from parasites, most common mechanisms of action include inhibition of MHC-II expression and antigenic presentation, an increase of nitric oxide production and the induction of regulatory cytokines (IL-10 and TGF-β) as well as a regulatory profile in macrophages and T cells. T-cell immunosuppression has also been described, but it is still an open question if cystatins act directly or it is mediated by innate immune cells (Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Kyewski, Sonnenburg and Lucius1997; Schonemeyer et al., Reference Schonemeyer, Lucius, Sonnenburg, Brattig, Sabat, Schilling, Bradley and Hartmann2001).

Production of a recombinant Al-CPI

Genome sequencing of A. suum led to identify a sequence with homology to other helminth cystatins. Based on this, we designed primers to amplify this sequence from a cDNA library of A. lumbricoides and the amplicon was cloned directly to the pQE30 vector. This led to the production of E. coli of a His-tagged protein with the functional activity of cysteine protease inhibition. This recombinant protein was injected in mice at different doses to test its toxicity, observing it is a safe product that does not induce abnormal physical or behavioural patterns in treated animals (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Barrios, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Franco, Ocampo and Caraballo2017).

Intestinal anti-inflammatory properties

Al-CPI has proved to prevent inflammation and tissue damage in a murine model of dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis and asthma, adding evidence on its anti-inflammatory effects on different contexts of exacerbated and pathologic immune responses. In the colitis model, recombinant Al-CPI (rAl-CPI) was intra-peritoneal administered daily for 15 days before and during the acute phase of inflammation. It was found that rAl-CPI reduced disease severity and epithelial damage. Colon samples of rAl-CPI mice had lower destruction of intestinal crypts and of goblet cell depletion. Mice treated with rAl-CPI showed high expression of IL-10 and TGF-β in colonic tissue together with the reduction of IL-6 and TNF-α RNA and protein levels (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Barrios, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Franco, Ocampo and Caraballo2017). Like Al-CPI, four other helminth cystatins with therapeutic potential on inflammatory bowel disease have been reported (Schnoeller et al., Reference Schnoeller, Rausch, Pillai, Avagyan, Wittig, Loddenkemper, Hamann, Hamelmann, Lucius and Hartmann2008; Jang et al., Reference Jang, Cho, Park, Kang, Na, Ahn, Kim and Yu2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xie, Yang, Wang, Yan, Zhong, Wang, Xu, Zhang, Liu and Shen2016; Togre et al., Reference Togre, Bhoj, Goswami, Tarnekar, Patil and Shende2018),

Anti-inflammatory properties in an allergy respiratory model

The house dust mite Blomia tropicalis is abundant in the Tropics, where it is an important source of allergens (Caraballo et al., Reference Caraballo, Valenta, Puerta, Pomes, Zakzuk, Fernandez-Caldas, Acevedo, Sanchez-Borges, Ansotegui, Zhang, van Hage, Fernandez, Arruda, Vrtala, Curin, Gronlund, Karsonova, Kilimajer, Riabova, Trifonova and Karaulov2020) and one of the main risk factors for asthma. In another study, we found that, similar to other helminth cystatins (Danilowicz-Luebert et al., Reference Danilowicz-Luebert, Steinfelder, Kuhl, Drozdenko, Lucius, Worm, Hamelmann and Hartmann2013; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Hu, Yang, Wei, Zhu, Liu, Feng, Yang, Okanurak, Li, Zeng, Zheng, Wu and Lv2015), Al-CPI reduces allergic airway inflammation, airway hyper-reactivity and other hallmarks of allergic inflammation after B. tropicalis sensitization, including eosinophil airways infiltration, goblet cell hyperplasia and elevated Th2 cytokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage and IgE production. In this model, rAl-CPI was intra-peritoneal administered, 4 h before sensitization, successfully reducing allergic inflammation (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Benedetti, Angelina, Palomares and Caraballo2019). This agreed with the observation that rAl-CPI induced an immunoregulatory response that included systemic IL-10 and TGF-β production as well as a strong IgG2 response that may dampen the allergenic effects of B. tropicalis (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Benedetti, Angelina, Palomares and Caraballo2019). Administration of rAl-CPI and B. tropicalis extract caused a significant elevation of IFNγ together with immunoregulatory cytokines, as observed for other Ascaris immunomodulators (Araujo et al., Reference Araujo, Perini, Martins, Macedo and Macedo-Soares2008). As Al-CPI, other helminth cystatins have been tested in models of allergic airway inflammation, showing similar results (Schnoeller et al., Reference Schnoeller, Rausch, Pillai, Avagyan, Wittig, Loddenkemper, Hamann, Hamelmann, Lucius and Hartmann2008; Danilowicz-Luebert et al., Reference Danilowicz-Luebert, Steinfelder, Kuhl, Drozdenko, Lucius, Worm, Hamelmann and Hartmann2013; Ziegler et al., Reference Ziegler, Rausch, Steinfelder, Klotz, Hepworth, Kuhl, Burda, Lucius and Hartmann2015).

Mechanisms of AL-CPI immunomodulation

Based on different observations, macrophages/monocytes and dendritic cells are thought to be the main target of cystatins immunomodulation. Klotz et al found that filarial cystatin is mainly captured by these cell populations when injected intraperitoneally (Klotz et al., Reference Klotz, Ziegler, Figueiredo, Rausch, Hepworth, Obsivac, Sers, Lang, Hammerstein and Lucius2011b). Also, monocyte depletion from peripheral blood mononuclear cells resulted in the abolition of the immunomodulatory effects of O. volvulus cystatin (Schonemeyer et al., Reference Schonemeyer, Lucius, Sonnenburg, Brattig, Sabat, Schilling, Bradley and Hartmann2001). It has been experimentally confirmed that several cystatins, including Al-CPI, block different cathepsins which participate in proteasome and proteolytic digestion in the endosomal compartment. Brugia malayi cystatin interferes directly with antigen processing and presentation by inhibiting cysteine protease activity in endolysosomes (Manoury et al., Reference Manoury, Gregory, Maizels and Watts2001; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Manoury, Balic, Watts and Maizels2005). Also, intraperitoneal treatment with recombinant Nippostrongylus brasiliensis cystatin (rNbCys) reduced 20% of the total activity of lysosomal cysteine proteases from the spleens or mesenteric lymph nodes. In this murine model, rNbCys reduced OVA-specific T-cell proliferation, probably due to its effects on antigen presentation (Dainichi et al., Reference Dainichi, Maekawa, Ishii, Zhang, Fawzy Nashed, Sakai, Takashima and Himeno2001). Al-CPI strongly inhibit cathepsin L, C and S (Mei et al., Reference Mei, Dong, Li, Liu, Liu, Sun, Liu, Su and Liu2014), and it is possible that this enzymatic activity partially supports its immunomodulatory effects.

Inhibition of antigen processing results in an impairment of expressing MHC and co-stimulatory molecules on the cell surface in APCs (Kobpornchai et al., Reference Kobpornchai, Flynn, Reamtong, Rittisoonthorn, Kosoltanapiwat, Boonnak, Ampawong, Jiratanh, Tattiyapong and Adisakwattana2020). Regarding Al-CPI, we found that it modulates the surface expression of co-stimulatory molecules (i.e. CD83 and CD86) in monocyte-derived human dendritic cells (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Benedetti, Angelina, Palomares and Caraballo2019). For other cystatins, it has been demonstrated by co-culture experiments that cystatin-primed APCs induce lower T-cell proliferation (Manoury et al., Reference Manoury, Gregory, Maizels and Watts2001; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Liu, Li, Chen, Liu, Liu and Su2013). Although not yet confirmed, our preliminary experiments showed that, in PBMC cultures, rAl-CPI significantly suppressed CD4 + CD3 + T-cell proliferation stimulated polyclonally with a reduction of IL-5 and an increase of IFN-γ levels, without changes in IL-10 production. Also, rAl-CPI reduced the B. tropicalis-induced production of IL-5 from allergic patients PBMC but not in healthy controls (Lozano et al., Reference Lozano, Zakzuk, Mercado and Caraballo2020). We also found that Al-CPI may have direct effects on other cell populations because it inhibited the proliferation (about 60%) of purified CD3 + CD4 + T cells stimulated with CD-Mix, raising new questions about its mechanism of action (Lozano et al., Reference Lozano, Zakzuk, Mercado and Caraballo2020). Hartmann et al. also found direct suppression of proliferation of purified CD3+ populations in murine T cells by AvCys (Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Kyewski, Sonnenburg and Lucius1997).

Besides its effects on antigen presentation, modulation of cytokine production by innate immune cells has been documented for different cystatins, both in human and mouse studies (Schonemeyer et al., Reference Schonemeyer, Lucius, Sonnenburg, Brattig, Sabat, Schilling, Bradley and Hartmann2001; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Liu, Yue, Chen, Song, Zhan and Wu2014). Cystatins induce primarily a strong IL-10 production. In the case of rAl-CPI, in vitro stimulation of mouse peritoneal macrophages and spleen cells induced a parallel increase of IL-10, TGFβ, IL-6 and IFNγ. Similarly, the filarial cystatin increased IL-6 and IL-8 concomitantly with IL-10 (Venugopal et al., Reference Venugopal, Mueller, Hartmann and Steinfelder2017). As with other parasite cystatins, despite inducing this moderate production of inflammatory cytokines, the net effect observed with LPS is inhibition of its capacity to elicit IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β secretion.

Although the inflammatory cytokines accompanying IL-10 production vary depending on the helminth cystatin or the cell population being analysed, this is an expected pattern of IL-10 secretion in innate immune cells. Several TLR ligands derived from bacteria, including LPS, induce IL-10 concomitant to the typical release of inflammatory cytokines (Saraiva and O'Garra, Reference Saraiva and O'Garra2010). For filarial cystatins, it has been shown that the role of ERK, MAPK and p38-dependent pathways, which are known to participate in bacterial products, activated TLR signalling, on IL-10 induction (Klotz et al., Reference Klotz, Ziegler, Figueiredo, Rausch, Hepworth, Obsivac, Sers, Lang, Hammerstein and Lucius2011b; Venugopal et al., Reference Venugopal, Mueller, Hartmann and Steinfelder2017). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that cystatins could have receptor-mediated effects, in addition to their inhibition of protease activity.

IL-10 was proposed to be a major mechanism of the protection from airway allergic inflammation induced by Acanthocheilonema vitae cystatin (Schnoeller et al., Reference Schnoeller, Rausch, Pillai, Avagyan, Wittig, Loddenkemper, Hamann, Hamelmann, Lucius and Hartmann2008). When we assessed the relevance of this cytokine as a mechanism of action of Al-CPI to prevent airway allergic inflammation, we found that IL-10R blockade reduced Treg cell numbers and the local IL-10 production in the lung, while significantly increasing type 2 humoral responses. Despite these cellular effects, it did not fully counteract the effects of rAl-CPI on airway inflammation in BAL neither bronchial hyper-reactivity, suggesting that other mechanisms may be involved in rAl-CPI-mediated modulation of allergic responses induced by B. tropicalis (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Zakzuk, Regino, Ahumada, Benedetti, Angelina, Palomares and Caraballo2019). In agreement with this, Schönemeyer et al. observed that addition of anti-IL-10 antibodies did not restore the inhibition of anti-CD3-induced proliferation of PBMC by O. volvulus cystatin. This suggests that IL-10 is not a major component of the rOv17-induced inhibition of T-cell proliferation (Schonemeyer et al., Reference Schonemeyer, Lucius, Sonnenburg, Brattig, Sabat, Schilling, Bradley and Hartmann2001). The role of other immunoregulatory mechanisms (TGF-β and Tregs) that are stimulated by cystatins, including rAl-CPI, deserves further investigation.

The increase of nitric oxide production (NO) has been proposed as another mechanism of action of cystatins. NO release has been associated with T-cell suppression, but it has also been reported that NO production by activated macrophages is associated with reduced parasite burden. rAl-CPI induced the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthetase (iNOS) in colonic tissue. Other cystatins, for example, those from B. malayi, O. volvulus and A. vitae (Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Schönemeyer, Sonnenburg, Vray and Lucius2002), induce NO secretion from primed macrophages. However, the relevance of these mechanisms on human macrophages remains to be investigated.

Concerns about the allergenic potential of cystatins have been raised by the recognition of the Anisakis simplex cystatin Ani s 4 as an allergen (Rodriguez-Mahillo et al., Reference Rodriguez-Mahillo, Gonzalez-Muñoz, Gomez-Aguado, Rodriguez-Perez, Corcuera, Caballero and Moneo2007) as well as cystatins from other non-helminth allergenic sources (Ichikawa et al., Reference Ichikawa, Vailes, Pomes and Chapman2001). Also, native A. vitae cystatin – which is a strong immunosuppressive helminth product – elicits β-hexosaminidase release in rat basophil leukaemia cells sensitized with sera from immunized gerbils (Hartmann et al., Reference Hartmann, Sollwedel, Hoffmann, Sonnenburg and Lucius2003), which suggest that it has allergenic activity. Although we could not definitely rule out this possibility, most of our results support that Al-CPI is poorly allergenic. First, bioinformatic analyses have shown that A. lumbricoides cystatins are homologous to other Anisakis simplex cystatins but not to Ani s 4. In addition, the nasal challenge with rAl-CPI did not induce an eosinophilic inflammatory response in airways, neither increased Penh values as observed with the B. tropicalis extract. Furthermore, rAl-CPI-specific IgE levels were undetectable in B. tropicalis sensitized/challenged mice perhaps justifying the failure of rAl-CPI to increase airway reactivity (supported by the Penh values) and induce passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (Coronado et al., Reference Coronado, Manotas, Zakzuk and Caraballo2015).

In summary, Al-CPI appears to be a safe product with tolerogenic effects on antigen-presenting cells and T cells that may be useful as an additional product for immunotherapy of asthma. Since humans have been naturally exposed to this protein through exposure to Ascaris without harmful reactions, this suggests that adverse effects associated with Al-CPI administration would be less probable. Although further deep characterization of its allergenic activity is necessary, preliminary data suggest it has low potential to induce allergic reactions. A graphic integration of the different effects of AL-CPI and the possible mechanisms of action leading to its anti-inflammatory properties is presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Graphic integration of the different immunomodulatory effects of Al-CPI and the possible mechanisms of action leading to its immunomodulatory properties.

Conclusions

The search for better anti-inflammatory compounds is the practical outcome of a long time basic research in the field of immunoparasitology. From epidemiological observations in humans, the field has advanced to the experimentation in animal models and ex vivo human cells using single purified molecules and multi-omics tools. In this race, an indefinite number of helminth-derived immunomodulators have been discovered, among them an A. lumbricoides cystatin, which has been evaluated by several strategies. Al-CPI is anti-inflammatory and non-toxic in mouse models of intestinal and lung inflammation. In human ex vivo experiments, it reduces the mite-induced IL-5 secretion from PBMC and the maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. In addition, Al-CPI is hypoallergenic. These characteristics suggest that it is potentially useful for treating INDs such as intestinal inflammatory disease and asthma, which means that further immunological and pharmacologic studies should be done. In addition, this and other helminth-immunomodulators will help to further explore the basic mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of IND.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of Cartagena and Minciencias, grants 406-2011; 699-2017 and 803-2018.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.