Introduction

The genus Posthodiplostomum Dubois, Reference Dubois1936 (Platyhelminthes: Diplostomidae) is a large and widely distributed group of digenetic trematodes in which larval stages infect snails and fish, and adults occur in the intestine of piscivorous birds. In freshwater fish hosts, metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum can negatively impact growth, change feeding rates (Osorio-Sarabia et al., Reference Osorio-Sarabia, Pérez-Ponce de León and García-Marquez1986), affect response to predation (Ondračková et al., Reference Ondračková, Dávidová, Gelnar and Jurajda2006) or cause mortality (Lane and Morris, Reference Lane and Morris2000).

Over the last decade, molecular studies have revealed novel species diversity and linked unknown larvae with identified adults in Posthodiplostomum (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Li, Makouloutou, Jimenez and Sato2012; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018; López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018; Pérez-Ponce de León et al., Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022). Several studies also demonstrated a need for revision in Posthodiplostomum and related genera (Blasco-Costa and Locke, Reference Blasco-Costa and Locke2017; López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018; Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Pulis, Fecchio, Schlosser and Tkach2019), culminating in the recent work of Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), who synonymized Ornithodiplostomum and Mesoophorodiplostomum with Posthodiplostomum and presented several new molecular life-stage linkages. These authors also found no support for the traditional subfamily system within the Diplostomidae, which rested partly on larval morphotypes shared among various genera. These include the neascus (from Greek, ‘new bladder’), a type of metacercariae that Hughes (Reference Hughes1927) named for the prominent reserve bladder that occurs in Posthodiplostomum and certain other diplostomid genera such as Uvulifer Yamaguti, 1934 and Crassiphiala Van Haitsma, 1925 (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1955; Gibson, Reference Gibson, Margolis and Kabata1996). Regardless of the status of neascus as a character within the Diplostomidae, it remains a useful concept for characterization of diplostomid diversity, as it effectively narrows down the identity of genera and species of metacercariae under consideration.

A review of molecular studies of Posthodiplostomum and other neascus shows strong geographic bias (Supplementary Table 1). Two-thirds (11/16) of all studies have been carried out in the Palaearctic (5) and Nearctic (6), with a sequencing effort disproportionately intense in North America (586/838 sequences). Probably as a consequence of this bias, most (at least 2/3) of the genetically distinguished Posthodiplostomum species come from North America (more precise estimates of regional species diversity are impeded by the use of different markers by different authors, raising the possibility of the same species delineated with different loci in different studies). Moreover, from the relatively few sequences sampled outside the Nearctic and Palaearctic regions (238/838), most (143) originate in a single recent study by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), 1 of only 3 with data from the Neotropics. This unbalanced sampling effort is particularly noteworthy because the diversity of fish and bird hosts is higher in Neotropic and Afrotropic regions compared to regions further north (Balian et al., Reference Balian, Segers, Lévêque and Martens2008), which suggests that parasite diversity is also higher. Still, while the study effort given in Supplementary Table 1 shows strong regional sampling and sequencing bias, it nonetheless represents an improvement. In 2016, <3% of specimens sequenced from the superfamily Diplostomoidea were obtained from the southern hemisphere and non-temperate regions (Blasco-Costa and Locke, Reference Blasco-Costa and Locke2017). Overall, however, additional data from neascus-forming taxa in the Neotropical regions are still needed to characterize the distribution, diversity and host-use patterns of Posthodiplostomum and related parasites.

Views of the identity and host specificity of metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum have changed in light of molecular data. In northeastern North America, for example, metacercariae of genetically distinguished species of Posthodiplostomum have proven to be specific to narrow ranges of centrarchid or leuciscid fish hosts (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018). Metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum minimum, Posthodiplostomum centrarchi and Posthodiplostomum sp. 8 have subsequently shown similar specificity in novel environments such as in Europe (Kvach et al., Reference Kvach, Jurajda, Bryjová, Trichkova, Ribeiro, Přikrylová and Ondračková2017; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017), Puerto Rico (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Van Dam, Caffara, Pinto, López-Hernández and Blanar2018) and Japan (Komatsu et al., Reference Komatsu, Itoh and Ogawa2020; Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021). In Central America, however, the metacercariae of most lineages of Posthodiplostomum surveyed by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) were found in multiple families of fish, suggesting patterns of host specificity initially observed in temperate regions may not generalize to tropical regions. The sequences from the extensive survey of Posthodiplostomum in Central America by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) have yet to be compared with those of Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), who sequenced adults across the Americas, partly because both studies were published nearly simultaneously.

In the Caribbean, little work has been conducted on metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum. Bunkley-Williams and Williams (Reference Bunkley-Williams and Williams1994) reported metacercariae of Po. minimum in centrarchids and in Poecilia reticulata, all of which are introduced to the island. Mohammed et al. (Reference Mohammed, King, Bentzen, Marcogliese, van Oosterhout and Lighten2020) reported metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum from the guppy Poe. reticulata in its native range (Trinidad). Aside from a DNA sequence and report of Po. centrarchi in Lepomis microlophus in Puerto Rico (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Van Dam, Caffara, Pinto, López-Hernández and Blanar2018), no genetic studies have been carried out to characterize the diversity of these worms in introduced or native freshwater fishes in the Caribbean region. The general trends of diversity that emerge from molecular surveys of diplostomoid and particularly neascus metacercariae suggest that diversity may be underestimated in the Caribbean and in Central and South America.

The present work aimed to characterize the diversity and host use of Posthodiplostomum and similar neascus-type metacercariae in fishes from western Puerto Rico, by integrating molecular and morphological analysis. Seven genetically distinct neascus-type metacercariae were found in native and introduced freshwater fishes, including 3 novel lineages, all of which display narrow specificity for their second-intermediate hosts on the island.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Most parasites studied herein were from fish from freshwater bodies in western Puerto Rico: Quebrada de Oro and Rio Yagüez in Mayagüez, a small pond in Centro Vacacional de Añasco, Cerrillos Reservoir near Ponce, and Rio Rosario in Maricao. Additional sequences were obtained from metacercariae from Gambusia affinis sampled in the Pascagoula River, Mississippi (USA), from Lepomis macrochirus in Lake Ontario and Lake Opinicon, Ontario (Canada), Lepomis gibbosus in St. Didace, Quebec (Canada), Micropterus salmoides in Canadarago Lake, New York (USA), and Micropterus dolomieu in Ottawa River, and Lake Saint Pierre, Quebec (Canada) and in Oaks Creek, New York (USA). In Puerto Rico, fish were caught using a backpack or boat-mounted electrofisher, while those from sites on the North American mainland were collected with a beach seine, cast net or hook and line. Fish collected in Puerto Rico were transported to the laboratory where they were maintained in aquaria until euthanization by immersion in clove oil solution until necropsy (Kvach et al., Reference Kvach, Jurajda, Bryjová, Trichkova, Ribeiro, Přikrylová and Ondračková2017). Fish were identified based on Sterba (Reference Sterba1967) as well as using molecular data (see below), and prior to necropsy were measured and weighed. Guppies and small fish were crushed whole between glass plates. Metacercariae were extracted from cysts manually with forceps for preservation in 95% alcohol and refrigeration at 4°C. Prevalence and mean abundance were calculated according to Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997).

At the same site of the Quebrada de Oro from which infected Poe. reticulata and Dajaus monticola were sampled, 1639 Tarebia granifera and 124 Melanoides tuberculata (Thiaridae), 747 Physa acuta (Physidae) and 202 Neritidae gen. sp. were collected. Ten Marisa cornuarietis were collected from the small pond in Añasco where infected Parachromis managuensis were obtained. No other snail species were observed at these localities. Most snails were housed in a small container with dechlorinated water for acclimation, placed in a multi-well culture plate and exposed to a 5 h light and dark cycle (a minority were dissected directly). Snails were examined twice for cercariae infections under a dissecting microscope. Non-shedding snails were crushed and examined for sporocysts.

Morphological study

Metacercariae were gradually rehydrated from 95% alcohol concentration to pure water, stained with Semichon's acid carmine, dehydrated in pure alcohol, cleared in clove oil and mounted on permanent slides using Permount toluene medium. Three types of morphological vouchers were deposited in the Museum of Southwestern Biology (MSB:Para:33294-301): paragenophores (from pairs of complete worms from the same individual host separated for either morphological or molecular evaluation), syngenophores (representatives from a different individual host of the same species collected from the same locality from which sequenced worms were obtained) and hologenophores (individual sub-sectioned worms from which DNA was extracted and sequenced) (Pleijel et al., Reference Pleijel, Jondelius, Norlinder, Nygren, Oxelman, Schander, Sundberg and Thollesson2008).

Morphological characterization of metacercariae was based on features studied by Dubois (Reference Dubois1970b), Athokpam and Tandon (Reference Athokpam and Tandon2014) and Stoyanov et al. (Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017) with metrical data reported in micrometres. Principal component analysis (PCA), analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) and permutational analysis of multivariate dispersion (PERMDISP) were performed using PRIMER-e software (Clarke and Gorley, Reference Clarke and Gorley2015) to assess morphometric variation within and between genetically distinguished species, based on Euclidean morphometric distances among specimens calculated from log-transformed measurements. Line drawings were made with the aid of a camera lucida Nikon Alphaphot YS and a drawing tube.

Molecular and phylogenetic analysis

Extraction of DNA from excysted metacercariae preserved in 95% ethanol employed the protocol for invertebrates of Ivanova et al. (Reference Ivanova, Dewaard and Hebert2006) and the Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding protocols. The DNA barcode region of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) gene was initially amplified using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and degenerate primers Dice1F forward with the Dice11-R including D3Ar sequence reverse primer (Van Steenkiste et al., Reference Van Steenkiste, Locke, Castelin, Marcogliese and Abbott2015) and/or primers MplatCOX1dF/R of Moszczynska et al. (Reference Moszczynska, Locke, McLaughlin, Marcogliese and Crease2009). In Posthodiplostomum and other members of the former Crassiphialinae, the barcode region of CO1 can be difficult to sequence bidirectionally because of poly-T regions (Van Steenkiste et al., Reference Van Steenkiste, Locke, Castelin, Marcogliese and Abbott2015). Nonetheless, this region of CO1 has utility because even lower quality contigs (single read, or only partially bidirectional reads) typically yield data allowing reliable discrimination of species. For example, Locke et al. (Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010) highlighted several species in which CO1 variation was likely inflated by problems with contig assembly and electropherogram quality, but the species distinguished have generally been supported in subsequent studies of the same taxa (Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018; Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021). In addition, the standardized use of this region of CO1 ensures comparability among a wide range of animals (Ondrejicka et al., Reference Ondrejicka, Locke, Morey, Borisenko and Hanner2014), including Posthodiplostomum and related taxa (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010, Reference Locke, Al-Nasiri, Caffara, Drago, Kalbe, Lapierre, McLaughlin, Nie, Overstreet, Souza, Takemoto and Marcogliese2015; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018; López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018).

Individual hosts suspected to be Pa. managuensis were sub-adult and did not show all diagnostic characters, and belong to Cichlidae, in which morphological variability can complicate identification (Sowersby, Reference Sowersby2017). In poeciliids, phenotypic plasticity and sexual dimorphism, with some species-specific characters only in males, can also hamper identifications (Schories et al., Reference Schories, Meyer and Schartl2009; Mise et al., Reference Mise, Souza, Pagotto and Goulart2015). Identification of Pa. managuensis and Poe. reticulata was therefore confirmed by amplification and sequencing CO1 using primers FishF1 (TCAACCAACCACAAAGACATTGGCAC) and FishR1 (TAGACTTCTGGGTGGCCAAAGAATCA) (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Zemlak, Innes, Last and Hebert2005) after extracting DNA from muscle tissue using a Qiagen DNeasy blood & tissue kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland, USA) following the manufacturer's protocols. The extracts were amplified in 25 μL reactions [3 μL template, 8.5 μL H2O, 0.5 μL of each primer, 12.5 μL Taq 2× Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ippswich, Massachusetts, USA)] with initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 0.5 min at 94°C, 0.5 min at 54°C and 1 min at 72°C; followed by a final 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were visualized on 1.0% agarose gels and sequenced at Genewiz (Genewiz, South Plainfield, New Jersey, USA).

Forward and reverse electropherograms were assembled using Geneious Prime v. 2020.2.3 (Biomatters Ltd., New Zealand). In many sequences obtained from parasites, a manual alignment was required to assemble contigs because unidirectional amplicons overlapped only in a poly-T region, where bidirectional contigs were obtained. Alignments were then generated using MUSCLE implemented in MEGA v.10.1.8 (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Li, Knyaz and Tamura2018) and pairwise uncorrected P-distances were calculated between and within clusters using the same program. Sequences from other studies used in the present analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 2. For phylogenetic reconstruction, maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) were used. The best nucleotide substitution model determined for CO1 (GTR + G + I) was selected based on the Bayesian information criterion (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Stecher, Li, Knyaz and Tamura2018). The ML analysis of non-redundant (<100% identical) CO1 sequences was carried out using RAxML v. 8 (Stamatakis, Reference Stamatakis2014) in Geneious v.11.2. Phylogenetic accuracy was estimated by bootstrapping the constructed trees with 500 replicates (Pattengale et al., Reference Pattengale, Alipour, Bininda-Emonds, Moret and Stamatakis2010). For BI gene tree estimation, MrBayes 3.2.6 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, Reference Huelsenbeck and Ronquist2001) was used with 2 runs of the Markov chain Monte Carlo for 1.1 million generations, sampled every 200 generations, a heating parameter value of 0.2, burn-in length of 100 000 and Diplostomum spathaceum set as outgroup. Species were delineated based on reciprocal monophyly in phylogenetic analysis and considering the magnitudes of P-distances within and between clades thus distinguished. Barcode index numbers (BINs), which are unique identifiers assigned in BOLD based on CO1 distance cluster quality (Ratnasingham and Hebert, Reference Ratnasingham and Hebert2007, Reference Ratnasingham and Hebert2013) were also used as a species-delineation proxy, and the geographic distributions, host spectra, infection site and morphology of specimens were also considered in determining species boundaries.

Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) sequenced CO1 in metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum in a wide range of fishes across Central America and obtained results highly relevant to the present study. However, sequences of DNA from Posthodiplostomum in the study by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) were from a different region of CO1 than those obtained in the present study, and direct comparison was not possible. Some sequences from Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), which all include the same region of CO1 sequenced herein, extend to the region sequenced by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), allowing indirect comparisons of the latter data with sequences in the present study. We used Discontinuous Megablast (Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Church, Federhen, Lash, Madden, Pontius, Schuler, Schriml, Sequeira, Tatusova and Wagner2003) to query CO1 sequences of Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021) against taxonomic identifiers created for lineages I–V in Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022).

Results

Infection levels

Neascus resembling Posthodiplostomum spp. were found in 64 of 170 (38%) fish belonging to 4 families collected in western Puerto Rico. Prevalence was highest in M. salmoides (17/29 infected), followed by Pa. managuensis (8/14), Poe. reticulata (28/58) and D. monticola (10/54) (Table 1). A total of 144 metacercariae were recovered from the mesentery, viscera and body cavity in Poe. reticulata, M. salmoides and L. microlophus, and from muscle tissue of Pa. managuensis and D. monticola. No diplostomid sporocysts or cercariae were recovered from snails.

Table 1. Origins and biometric parameters (mean ± standard deviation in parentheses) of fish collected in Puerto Rico and other localities in the present study

ND, no data.

Molecular analyses

Amplification and direct sequencing of CO1 was successful in 64/88 specimens from Puerto Rico (GenBank accession numbers: OP071162–225, Supplementary Table 3). Forward and reverse chromatograms were aligned to generate bidirectional contigs when possible. In most samples, a 13 bp poly-T region common in CO1 in diplostomids (Van Steenkiste et al., Reference Van Steenkiste, Locke, Castelin, Marcogliese and Abbott2015) caused short or low-quality electropherograms in downstream sequencing and contigs were therefore based on single-direction reads assembled on either side of the poly-T span. After including previously published data, and removing identical and short sequences (<300 bp), the final alignment of 78 CO1 consensus sequences was 441 bp in length. All study sequences were between 14.5 and 22.4% divergent from those of Posthodiplostomum brevicaudatum (KX931418-20), which were excluded from subsequent analysis because they resulted in a shortened contiguous alignment. In ML and BI analyses, CO1 sequences from specimens collected in the present study fell into 7 well-supported and reciprocally monophyletic species-level clades (hereafter, species) (Fig. 1) with interspecific divergence of at least 6.4% and mean intraspecific mean distances of 0.9% (range 0–3.8%) (Table 2). Deeper nodes in the ML and BI phylogenies were generally weakly supported (bootstrap support <70%, posterior probability <0.9), but in both ML and BI trees sequences generated in the present study fell into a monophyletic clade consisting of data from Posthodiplostomum spp. Separate ML/BI analysis based on translated amino acids, or on only the first 2 codons, did not clarify relationships, and therefore, only the ML tree based on all nucleotide positions is shown herein (Fig. 1). Sequences from the present study were comprised of 3 species from Poe. reticulata (body cavity) (Posthodiplostomum spp. 23, 24 and 26), 1 from D. monticola (muscle) (Posthodiplostomum sp. 25), 1 from Pa. managuensis (muscle) (Posthodiplostomum macrocotyle), 1 from M. dolomieu and M. salmoides (liver) (Posthodiplostomum sp. 8) and 1 from L. macrochirus (liver, kidney) and L. gibbosus (heart, liver) (Po. centrarchi). Most of the species we distinguished were consistent with the BINs assigned in BOLD (Ratnasingham and Hebert, Reference Ratnasingham and Hebert2007, Reference Ratnasingham and Hebert2013), except in Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 and 24, which each contained 2 BINs. Within Posthodiplostomum sp. 23, the BIN algorithm separated 2 sequences from parasites from G. affinis in Mississippi (BIN: AAM7098) from 7 sequences from parasites from Poe. reticulata in Puerto Rico in the present study, and 1 from an adult from Ardea herodias from Georgia, USA, from Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021) (BIN: ADE4068), based on BOLD calculations of 2.52% CO1 distance between these BINs. Nonetheless, we provisionally place both clusters of sequences in AAM7098 and ADE4068 within Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 (following nomenclature of Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), because this level of genetic divergence is within that recorded in other studies of Posthodiplostomum (e.g. Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), intermediate hosts belong to the same family (Poeciliidae), the data originate from a plausible geographic scope for a single species of Posthodiplostomum and genetic distances based on our own alignments differed (Table 2). In what we consider to be Posthodiplostomum sp. 24, 2 BINs (AEF4897, n = 5; AEF4552, n = 1) differing by 3.81% in CO1 were distinguished on BOLD. Although this is an unusually high level of intraspecific variation in CO1 in Posthodiplostomum, in the absence of any other evidence, such as differential host use, we provisionally assign sequences in both AEF4897 and AEF4552 to a single putative species. Notably, the single specimen in AEF4552 was found in the same individual guppy as a specimen of AEF4897.

Fig. 1. Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree of 75 sequences of partial CO1 from Posthodiplostomum spp. and other diplostomids using the GTR + G + I model of nucleotide evolution. Nodes with ML bootstrap values above 70% in 1000 replicates are annotated with ML bootstrap support/BI posterior probability based on 8252 trees. Species present in Puerto Rico are indicated by shaded boxes and annotated with hosts and geographic realms (purple square = Neotropical; green circle = Nearctic; red triangle = Palaearctic); those newly characterized are in bold text.

Table 2. Mean uncorrected P-distance (%) in partial CO1 among and within species of Posthodiplostomum from Puerto Rico (ranges in parentheses) and heterospecific species with minimal genetic distance (i.e. nearest neighbour)

Four of the 7 species sequenced in the present study presented species-level matches with published data. Six CO1 sequences from Po. centrarchi in L. macrochirus from Ontario were 99–100% similar to those of Po. centrarchi from Canada, Europe and Puerto Rico (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010, Reference Locke, Van Dam, Caffara, Pinto, López-Hernández and Blanar2018; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017). Six CO1 sequences from metacercariae from the liver of M. salmoides from Cerrillos Reservoir matched (98–99.8%) Posthodiplostomum sp. 8 from Micropterus spp. from North America (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018). Fifteen CO1 sequences from metacercariae from the muscle of Pa. managuensis showed 100% identity with adult Po. macrocotyle from Busarellus nigricollis from the Pantanal, Brazil (Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021). Eight CO1 sequences from metacercariae infecting Poe. reticulata and 2 of G. affinis in Mississippi matched (99.6%) an adult of Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 from A. herodias in Georgia, USA (Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021). The CO1 sequences of Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 from Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021) were long enough for comparison with data from Posthodiplostomum of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), but no species-level match was observed for this or other species in the 2 studies (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of genetic distances (uncorrected-P) among sequences of CO1 from species of Posthodiplostomum in Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021) and Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), based on BLAST searches

Preliminary morphological identifications of representative cichlid and poeciliid hosts were supported with CO1 data. A 595-bp CO1 sequence from a sub-adult cichlid (OP071160) collected in Añasco was 99.5–100% identical to 12 CO1 sequences of Pa. managuensis in GenBank (HQ654748-52, HQ654748, KP728467, KP728467, MG496183-6). A 596-bp CO1 sequence from a guppy (OP071161) collected in Quebrada de Oro, Mayagüez, averaged 97.66 (range 86.6–99.8% similarity) to 63 sequences from Poe. reticulata in GenBank. The lower range of these similarities was driven by an unpublished sequence (MT428036) attributed to Poe. reticulata that differed from other CO1 sequences from Poe. reticulata by ≥12.4%; MT428036 is likely misidentified as it has high similarity (>99%) with numerous CO1 sequences from Poecilia gillii, Poecilia mexicana, Poecilia orri and Poecilia sphenops, which form part of a species complex that does not include Poe. reticulata (Bagley et al., Reference Bagley, Alda, Breitman, Bermingham, van den Berghe and Johnson2015). Excluding MT428036, the CO1 sequence from Poe. reticulata in Quebrada de Oro averaged 97.83 (range 94.8–99.8% similarity) to the remaining 62 CO1 sequences from Poe. reticulata in GenBank. Tissue vouchers from these 2 sequenced fish hosts were deposited at the Museum of Southwestern Biology (Poe. reticulata MSB:Host:24820, Pa. managuensis MSB:Host:24821).

Morphology of parasites

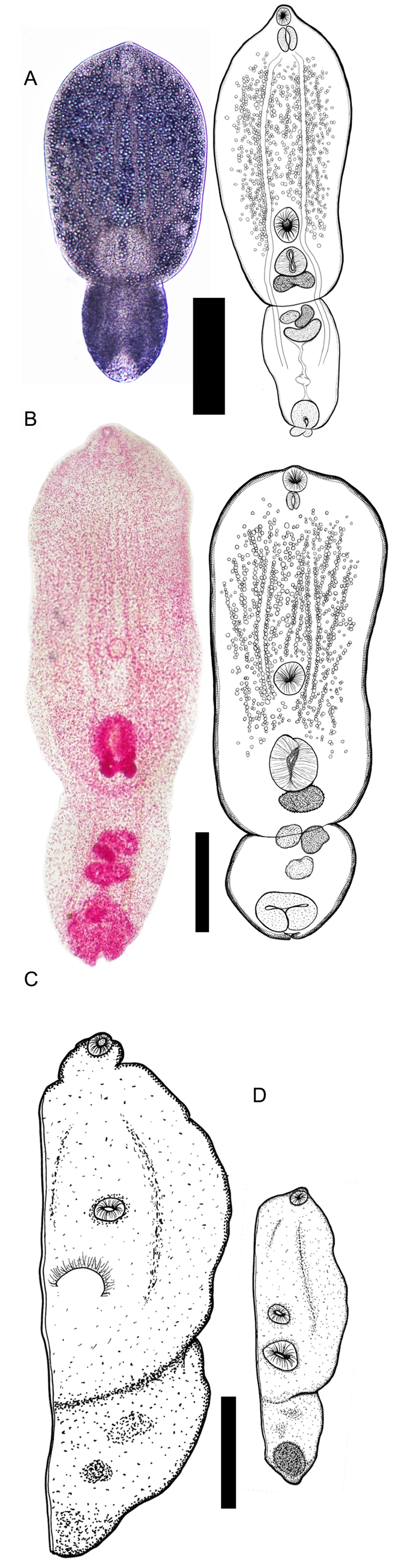

A total of 147 neascus metacercariae were recovered from fish in western Puerto Rico, of which 66 were from the body cavity of Poe. reticulata, 37 were from muscle of D. monticola and 44 from muscle of Pa. managuensis. For morphometric analysis, 105 worms were stained and measured, including vouchered metacercariae from centrarchid hosts sampled in Canada and USA. The morphology of the neascus metacercariae was consistent with Posthodiplostomum spp. Worms were in voluminous cysts, exhibited a bipartite body, and lacked lateral pseudosuckers in the foliaceous prosoma (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Line drawings and whole mounts of metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum from fish collected in western Puerto Rico. (A) Paragenophores of Posthodiplostomum macrocotyle from the muscle of Parachromis managuensis. Scale bar: 100 μm. Left specimen is a temporary mount of a live, unstained specimen. (B) Paragenophores of Posthodiplostomum sp. 25 from the muscle of Dajaus monticola. Left specimen is stained and permanently mounted. (C, D) Hologenophores of metacercariae from body cavity of a single individual Poecilia reticulata. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Posthodiplostomum sp. 23; (D) Posthodiplostomum sp. 24.

The 105 specimens studied morphometrically included 6 hologenophores from 2 Posthodiplostomum species from Poe. reticulata (Posthodiplostomum spp. 23 and 24; no hologenophore was obtained from Posthodiplostomum sp. 26). All voucher specimens, including all those from Poe. reticulata that likely comprise a mixture of Posthodiplostomum spp. 23, 24 and 26, were characterized morphometrically with accompanying statistical analysis of morphometric distances. Because only a single species of Posthodiplostomum distinguished genetically was recovered from each of Pa. managuensis, D. monticola, Lepomis spp. and Micropterus spp., unsequenced voucher specimens from each of these hosts were considered para- or syngenophores for purposes of morphological characterization. Consistent with this assumption, metacercariae from the same host species were more morphometrically similar than those from different host species (ANOSIM global: R = 0.389, P = 0.001, 999 permutations of Euclidean distances based on 16 log-transformed measurements). Morphometric distances between worms from all pairs of host species were significantly greater than those within host species (pairwise ANOSIM: R = 0.219–0.966, P ≤ 0.001) except between worms from Lepomis and Micropterus (R = 0.004, P = 0.396). The greatest morphometric distances were between parasites from Pa. managuensis and those from D. monticola (R = 0.902, P = 0.001) and Micropterus spp. (R = 0.966, P = 0.002).

These differences are apparent in PCA, in which the first 2 axes explain the 75.3% of total morphometric variation (Fig. 3). Along PC1 (62.8% of total variation), worms from Pa. managuensis were morphometrically distinct from all others except for some originating from Poe. reticulata. Along PC2, 2 groups were formed, one scoring positively and comprising metacercariae from all host species, and a second scoring negatively and comprising a subset of worms from Poe. reticulata and D. monticola. Morphometric variability was highest in worms from Poe. reticulata, which were widely dispersed along PC1 and PC2. Morphometric dispersion (approximated in 2 dimensions by the spread of the data cloud in Fig. 3) differed among metacercariae from different host species (PERMDISP: F ratio = 4.435, P = 0.0024). Worms from Poe. reticulata presented the highest morphometric dispersion, with an average spread to median of morphometric distances of 1.360 (s.d. 0.075), followed by parasites from D. monticola (average spread to median = 1.048, s.d. 0.053). The high morphometric variability of specimens from Poe. reticulata is consistent with the molecular results indicating the presence of 3 species (Posthodiplostomum spp. 23, 24 and 26) in this host. Consequently, only hologenophores were used to describe metacercariae of species from Poe. reticulata, while other species were characterized also based on para- and syngenophores (Table 4, see sections Descriptions and Remarks).

Fig. 3. Principal Component Analysis of morphometric distances among 105 metacercariae of species of Posthodiplostomum infecting fishes in Puerto Rico. Axes (PC1, PC2) are labelled with amount of morphometric variation explained and points with host species (see inset legend). Euclidean morphometric distances are based on 16 log-transformed measurements.

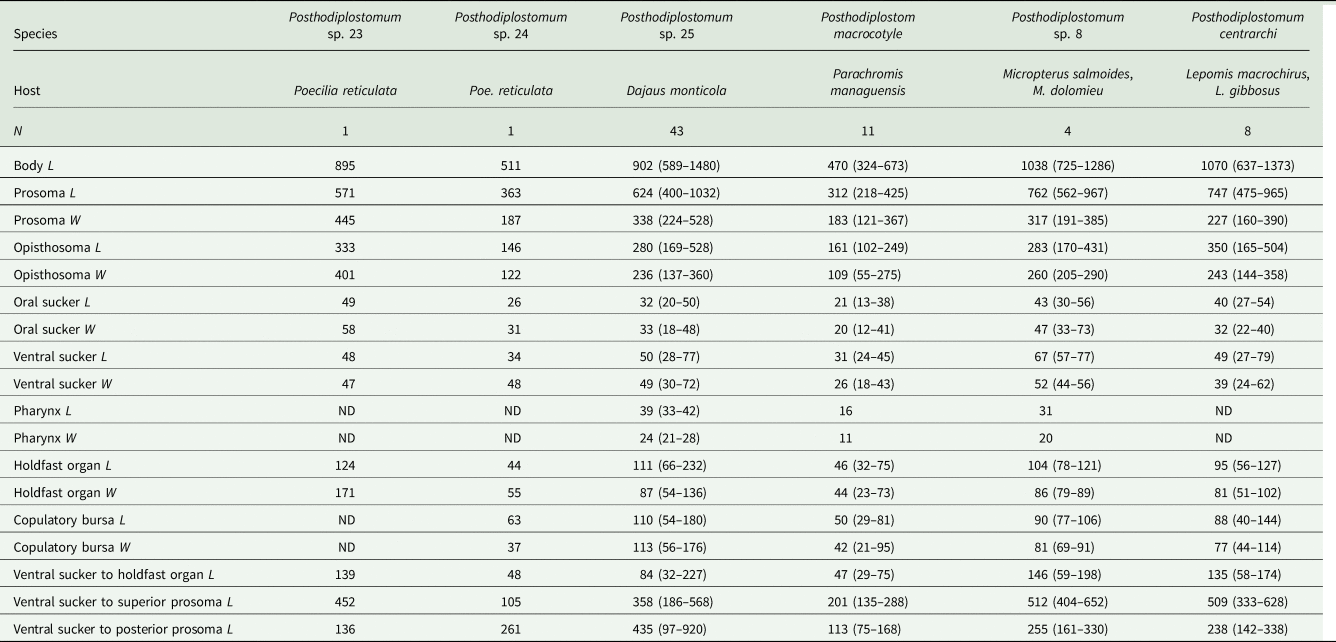

Table 4. Comparative morphometrics of metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum from the present study: mean (range in parentheses) in μm

L, length; W, width; ND, no data.

Descriptions

Posthodiplostomum sp. 23

Host: Poecilia reticulata, Gambusia affinis (Poeciliidae).

Localities: Quebrada de Oro (18.2129, −67.1429), Mayagüez, Puerto Rico; Pascagoula River, Mississippi, USA.

Site of infection: mesentery.

Voucher specimen: MSB:Para:33301.

BINs: ADE4068, AAM7098.

GenBank: OP071188-97.

Description based on 1 hologenophore from Poe. reticulata from Quebrada de Oro (Fig. 2C; Table 4). Body slightly bipartite, with prosoma elongated and round, opisthosoma round. Prepharynx not observed. Oral sucker oval, well developed, slightly larger than ventral sucker. Muscular holdfast organ close to ventral sucker and to posterior margin of prosoma. Copulatory bursa and genital primordia not visible. In spacious, colourless, thin-walled cysts.

Posthodiplostomum sp. 24

Host: Poecilia reticulata (Poeciliidae).

Locality: Quebrada de Oro (18.2129, −67.1429), Mayagüez, Puerto Rico.

Site of infection: mesentery.

Voucher specimen: MSB:Para:33296.

BINs: AEF4897, AEF4552.

GenBank: OP071198-205.

Description based on 1 hologenophore (Fig. 2D; Table 4). Body small. Prosoma spatulated and bigger than opisthosoma, separated by marked constriction. Oral sucker terminal and oval. Ventral sucker oval, muscular and slightly larger than oral sucker. Prepharynx not observed. Oval holdfast organ well-developed located close to ventral sucker. Holdfast gland not observed. Testes and ovary in opisthosoma, poorly developed. Copulatory bursa terminal and elongate. In spacious, colourless, thin-walled cysts.

Posthodiplostomum sp. 25

Host: Dajaus monticola (Mugilidae).

Localities: Rio Yaguez (18.2051, −67.1299) and Quebrada de Oro (18.2129, −67.1429), Mayagüez, Puerto Rico.

Site of infection: muscle.

Voucher specimens: MSB:Para:33294-5, MSB:Para:33298.

BIN: ADE2986.

GenBank: OP071206-18.

Description based on 12 paragenophores (Fig. 2B; Table 4). Prosoma spatulated, separated by marked constriction from oval or round opisthosoma. Oral sucker small, round, at anterior extremity of prosoma. Prepharynx not observed, pharynx oval, longer than wide, observed in 4 specimens. Ventral sucker usually larger than oral sucker, located in middle of prosoma, well-separated from holdfast organ. Holdfast organ large, slightly oval, holdfast glands usually absent. Testis and ovary poorly differentiated, copulatory bursa at posterior of opisthosoma, rounded. In yellowish, semi-opaque, thicker-walled cysts, possibly consisting partly of encapsulating tissue of host origin.

Posthodiplostomum macrocotyle Dubois, Reference Dubois1937

Host: Parachromis managuensis (Cichlidae).

Locality: Tres Hermanos National Park (18.2941, −67.2009), Añasco, Puerto Rico.

Site of infection: muscle.

Voucher specimens: MSB:Para:33297, MSB:Para:33299-300.

BIN: AEF4898.

GenBank: OP071172-87.

Description based on 11 paragenophores (Fig. 2A; Table 4). Body small, distinctly bipartite. Prosoma spatulated, opisthosoma oval. Prepharynx not observed. Oral sucker elongated slightly from superior of prosoma, but round. Muscular oval ventral sucker located close to margin anterior to holdfast organ. Holdfast organ smaller, closest to posterior margin of prosoma. Copulatory bursa oval, contractile. In colourless, transparent, thin-walled cysts.

Remarks

The metacercariae of the 7 genetically distinguished species reported herein were assigned to the genus Posthodiplostomum based on morphological features such as the bipartite body divided into a foliate prosoma lacking pseudosuckers and a roughly spherical opisthoma, as well as molecular phylogenetic analysis. Morphological characterization of Posthodiplostomum spp. 23, 24 was limited to hologenophores (Table 4; Fig. 2) and no morphological characterization of Posthodiplostomum sp. 26 was possible. Posthodiplostomum spp. 23, 24 and 26 were all from the same host (Poe. reticulata), sometimes in mixed infections, making it unclear whether unsequenced specimens could be considered paragenophores of Posthodiplostomum sp. 23, 24 or 26. Consistent with the higher species diversity of parasites in Poe. reticulata, morphometric heterogeneity was significantly greater in vouchered metacercariae from guppies than in parasites from other hosts, in which only single species of Posthodiplostomum were detected in DNA sequences. Despite these limitations, most of the genetically distinguished species can be differentiated from each other based on straightforward characters such as total length. For example, hologenophores of Posthodiplostomum spp. 23 and 24 differ markedly in size (Fig. 2; Table 4) and, notably, these 2 metacercariae were collected from the same individual guppy. The metacercaria of Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 resembles that of Posthodiplostomum nanum from guppies as described by López-Hernández et al. (Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018), but in Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 the oral sucker is larger (49 × 58 μm vs maximum of 41 × 41 μm in 20 metacercariae of Po. nanum, López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018), and the ventral sucker is further from the tribocytic organ (cf. Fig. 2 herein and Fig. 1D in López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018).

Metacercariae of Po. macrocotyle were the smallest worms, overlapping in total length only with Posthodiplostomum sp. 24 and smaller individuals of Posthodiplostomum sp. 25. These 2 smallest species, Posthodiplostomum sp. 24 and Po. macrocotyle, can be distinguished by the width of the ventral sucker and the distances between the ventral sucker and the anterior and posterior margins of the prosoma.

Metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum sp. 8 and Po. centrarchi, the 2 species infecting centrarchid hosts, were generally larger than those of other species encountered. As in Kvach et al. (Reference Kvach, Jurajda, Bryjová, Trichkova, Ribeiro, Přikrylová and Ondračková2017), morphological distinctions were not observed between the metacercariae of these 2 species, which can be distinguished genetically and by their tendency to infect either Lepomis or Micropterus (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018).

Metacercarial paragenophores of Posthodiplostomum sp. 25, from the muscle of D. monticola, were variable in size, such that some specimens were as small as the smaller species (Posthodiplostomum sp. 24 and Po. macrocotyle) and some were as large as the larger species from centrarchids. Unlike the other species studied here, metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum sp. 25 were usually found in a pale-yellow capsule or cyst, possibly including tissue of host origin.

In Posthodiplostomum spp. 8, 24, 25 and Po. centrarchi, 69–73% of the total body length is accounted for by the prosoma, while in Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 and Po. macrocotyle, the prosoma represented 64–66% of the total length. The length of the ventral sucker was 13% of the length of the prosoma in Posthodiplostomum sp. 24, while it accounted for 6–8% of the prosoma length in Po. centrarchi and Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 and 25.

Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) recently reported 6 lineages of Posthodiplostomum infecting various fishes throughout Central America, but using internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rDNA and a different region of CO1 than sequenced in the present study. Consequently, morphological comparisons between lineages of Posthodiplostomum encountered in the same host taxa by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) and in the present study are of particular interest. Based on specimen drawings in Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), the 3 lineages that these authors recovered from poeciliids have estimated total lengths of 971 (lineage I), 1045 (lineage II) and 948 (lineage IV) μm. The hologenophore of one of the species recovered from Poe. reticulata in Puerto Rico, Posthodiplostomum sp. 24, is substantially smaller (Table 4). The oral sucker of the hologenophore of Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 (also from Poe. reticulata) was larger than those of these lineages (estimated to be 14, 25 and 14 μm in diameter in lineages I, II and IV, respectively). Interestingly, both Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 and lineage IV in Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) are closely related to Po. nanum, and other than the aforementioned difference in the size of the oral sucker, appear morphologically similar. However, CO1 differs substantially in Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 and lineage IV, indicating they are different species (see Remarks above on MZ707217, and Table 3).

Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) recovered lineage III from cichlids in the amphilophine clade (Archocentrus nigrofasciata, Amatitlania siquia) collected in the native range of Pa. managuensis, also an amphilophine (Concheiro Pérez et al., Reference Concheiro Pérez, Říčan, Ortí, Bermingham, Doadrio and Zardoya2007). However, lineage III appears to be 1725 μm in total length, much larger than any specimens we recovered, particularly the diminutive metacercariae of Po. macrocotyle that originated in Pa. managuensis introduced in Puerto Rico.

Discussion

Unrecognized species diversity frequently emerges from molecular surveys of diplostomoids (e.g. Blasco-Costa and Locke, Reference Blasco-Costa and Locke2017) and was therefore expected in this survey of metacercariae in Puerto Rico. Of 7 genetically distinct species of Posthodiplostomum detected, 3 are probably new additions to sequence databases and the present records add host and geographic range data for the other 4. The present results suggest that substantial species diversity remains to be discovered in Posthodiplostomum in this region, and point to certain host taxa as deserving of further parasitological study.

In phylogenetic analysis, all CO1 sequences fell within a clade composed of species of Posthodiplostomum, corroborating morphological identifications at the genus level. Within most of the 7 well-supported species-level clades, CO1 varied by <2%, despite the inclusion of data from geographically distant samples, such as Po. centrarchi from Canada and Europe, Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 from Georgia, USA and Po. macrocotyle from the Pantanal, Brazil. In contrast, interspecific CO1 distances were at least 6.4%, which exceeds the smallest interspecific CO1 distances (5.3%) reported by Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), in a wide survey in which many species were distinguished with the added support of 28S and morphology from adults. When considered alongside differences in metacercarial morphology, host use and infection sites, and reciprocal monophyly in phylogenetic analysis, this gap in CO1 distances constitutes strong evidence the sympatric lineages we encountered correspond to 7 distinct species.

Molecular data show that 4 of 7 species of Posthodiplostomum in Puerto Rico are conspecific with those sequenced in other studies, yielding new information on host spectra and geographic distributions of these parasites. One of these 4 species-level matches was published by Locke et al. (Reference Locke, Van Dam, Caffara, Pinto, López-Hernández and Blanar2018), i.e. identical CO1 in Po. centrarchi from North American mainland samples (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018) and from L. microlophus in Puerto Rico. The other 3 species-level matches are newly reported here. CO1 from metacercariae from Poe. reticulata in Puerto Rico and from another poeciliid, G. affinis, in Mississippi matches Posthodiplostomum sp. 23, previously known only from A. herodias in the southeastern USA (Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021).

Phylogenetic analysis indicates Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 is closely related to Po. nanum (this also emerges from analysis of 28S by Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021). Interestingly, similar to Posthodiplostomum sp. 23, Po. nanum is also known from Poe. reticulata (López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018) and has also recently been recovered from an ardeid (A. herodias) in the southeastern USA (Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021). Based on sequences of ITS rDNA, Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) placed lineage IV, from P. sphenops and Profundulus spp. from Oaxaca, Mexico in a clade with Po. nanum (along with an unidentified species from Tilapia sparrmanii from South Africa, Hoogendoorn et al., Reference Hoogendoorn, Smit and Kudlai2019). However, by comparison with longer sequences of Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 (e.g. MZ707217, 1024 bp) of Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), a species-level match between Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 in the present study with lineage IV of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) can be excluded. Taken together, these findings indicate that 3 closely related species of Posthodiplostomum share overlapping geographic distributions across the Americas, and similar hosts in their life cycles [Po. nanum, Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 of Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021) and Posthodiplostomum lineage IV of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) all have metacercariae in Poecilia, and adults of Po. nanum and Posthodiplostomum sp. 23 occur in A. herodias in North America].

The present results also provide the first molecular links to larval forms of Po. macrocotyle, the first account of its metacercarial morphology, and the first report of this species outside South America. Morphology-based records of adults of Po. macrocotyle originate from diverse fish-eating birds [Spheniscus magellanicus (Sphenisciformes), B. nigricollis (Accipitriformes), several ardeids (Pelecaniformes) and the type host Rynchops niger (Charadriiformes)] in Cuba, Brazil and Argentina (Dubois, Reference Dubois1937, Reference Dubois1970a, Reference Dubois1970b; Dubois and Macko, Reference Dubois and Macko1972; Travassos et al., Reference Travassos, Teixeira de Freitas and Koh1969; Brandaõ et al., Reference Brandaõ, Luque, Szholz and Kostadinova2013; Drago et al., Reference Drago, Lunaschi and Draghi2014). The CO1 obtained from metacercariae from the introduced jaguar guapote Pa. managuensis in Puerto Rico matches with adults from the accipitrid B. nigricollis in the Pantanal, Brazil, which have recently been sequenced by Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021). Previous reports of metacercariae of Po. macrocotyle from South American cichlids were questionable. Azevedo et al. (Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2006, Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2011) and Mesquita et al. (Reference Mesquita, Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2011) identified Po. macrocotyle metacercariae from cichlid (Geophagus brasiliensis) and catfish (Trachelyopterus striatulus) hosts in Brazil, but provided no support other than citation of Travassos et al. (Reference Travassos, Teixeira de Freitas and Koh1969), who only reproduced the description of Dubois (Reference Dubois1937, Reference Dubois1938) of the adult form, which presents ambiguous morphological relation to the metacercaria. For example, Travassos et al. (Reference Travassos, Teixeira de Freitas and Koh1969) reported the adult of Po. macrocotyle to be 890–1170 μm in total length, much larger than the metacercariae observed herein. Moreover, cysts of Po. macrocotyle were only found in muscle in the present study, while these earlier works reported this species from unusual sites such as buccal cavity and stomach (Azevedo et al., Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2006; Mesquita et al., Reference Mesquita, Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2011). The parasites reported as Po. macrocotyle by Azevedo et al. (Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2006, Reference Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2011) and Mesquita et al. (Reference Mesquita, Azevedo, Abdallah and Luque2011) are therefore suspected to represent a different species.

Cichlids are one of the most species-rich and widespread families of freshwater fish, and are often reported to harbour Posthodiplostomum or neascus-type parasites, particularly in the Neotropics (Salgado-Maldonado et al., Reference Salgado-Maldonado, Mercado-Silva, Cabañas-Carranza, Caspeta-Mandujano, Aguilar-Aguilar and Iñiguez2004, Reference Salgado-Maldonado, Caspeta-Mandujano, Martínez-Ramírez, Montoya-Mendoza and Mendoza-Franco2020; Neves et al., Reference Neves, Pereira, Tavares-Dias and Luque2013; Tavares-Dias and Oliveira, Reference Tavares-Dias and Oliveira2017; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Oliveira, Neves and Tavares-Dias2018; Salgado et al., Reference Salgado-Maldonado, Caspeta-Mandujano, Martínez-Ramírez, Montoya-Mendoza and Mendoza-Franco2020). Two of 6 molecular lineages (III and VI) of Posthodiplostomum sampled by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) across North and Middle America were from cichlids, 1 lineage widely distributed between northeastern Mexico and Costa Rica, and the other recovered only in southeastern Mexico. The only other molecular data from neascus from this host family are those from Posthodiplostomum sp. 9 from T. sparrmanii from South Africa (Hoogendoorn et al., Reference Hoogendoorn, Smit and Kudlai2019). Despite these efforts, this is the first report of Posthodiplostomum in the jaguar guapote Pa. managuensis, one of the largest (Conkel, Reference Conkel1993) and most widely introduced (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Williams and Power2020) cichlids.

The remaining 2 CO1-based matches with prior work were in species of Posthodiplostomum (Po. centrarchi and Posthodiplostomum sp. 8) from centrarchid fish hosts. Posthodiplostomum centrarchi was previously found in L. microlophus introduced to the island (Locke et al., Reference Locke, Van Dam, Caffara, Pinto, López-Hernández and Blanar2018), while the present record extends the geographic distribution of Posthodiplostomum sp. 8 to the Caribbean. Both these species are known mainly from North America (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018; Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), but have also been introduced in Europe (Kvach et al., Reference Kvach, Jurajda, Bryjová, Trichkova, Ribeiro, Přikrylová and Ondračková2017). Based on ITS sequences, Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) cast doubt on the separation of Posthodiplostomum sp. 8 and Po. centrarchi, but we found unambiguous separation of these species in analysis of available CO1 sequences, and their exclusive recovery from different centrarchid hosts in multiple studies provides strong support of their distinct status.

The 3 remaining species detected in the present study (Posthodiplostomum spp. 24, 25 and 26) have not been reported previously, at least not using the barcode locus of the CO1 gene. Posthodiplostomum sp. 25 from the muscle of D. monticola (Mugilidae) is new in terms of not being previously sequenced, as well as a new record for the genus Posthodiplostomum in this host. Parasitological surveys of D. monticola in Mexico (Salgado-Maldonado et al., Reference Salgado-Maldonado, Mercado-Silva, Cabañas-Carranza, Caspeta-Mandujano, Aguilar-Aguilar and Iñiguez2004, Reference Salgado-Maldonado, Caspeta-Mandujano, Martínez-Ramírez, Montoya-Mendoza and Mendoza-Franco2020) and Costa Rica (Sandlund et al., Reference Sandlund, Daverdin, Choudhury, Brooks and Diserud2010) have reported few digeneans. Although D. monticola is common and abundant in Puerto Rico (Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Cooney and Brown2007; Cancel-Villamil and Locke, Reference Cancel-Villamil and Locke2022), and the present results indicate infections with Posthodiplostomum sp. 25 are not uncommon, no neascus has been reported previously in this host. The only helminths reported from D. monticola in Puerto Rico are cystidicolid nematodes in the genus Spinitectus and metacercariae of Echinochasmus donaldsoni (Bunkley-Williams and Williams, Reference Bunkley-Williams and Williams1994; Dyer et al., Reference Dyer, Williams and Williams1998). Compared with the numerous records in the wide spectra of leuciscids and centrarchids (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1999), Posthodiplostomum spp. are infrequently reported from a small number of fishes of the Mugilidae (Domitch and Sarabeev, Reference Domitch and Sarabeev2000; Özer and Yilmaz Kirca, Reference Özer and Yilmaz Kirca2015; Sarabeev et al., Reference Sarabeev, Balbuena and Morand2017).

The 2 remaining species of Posthodiplostomum newly sequenced herein (spp. 24 and 26) were both from the guppy Poe. reticulata, a fish native to Trinidad and Venezuela that has been introduced widely (Deacon et al., Reference Deacon, Ramnarine and Magurran2011). The poeciliids are a species-rich group of Neotropical origin, but molecular work on their parasites has just begun (López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018; Pérez-Ponce de León et al., Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022). Metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum were recorded in 11% of 270 Poe. reticulata sampled in its native range in Trinidad (Mohammed et al., Reference Mohammed, King, Bentzen, Marcogliese, van Oosterhout and Lighten2020), and Po. nanum has been recorded in Poe. reticulata in Brazil (López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018). Hoffman (Reference Hoffman1999) compiled records of metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum (as Po. minimum) in G. affinis in Tennessee and in Poe. mexicana in Mexico. Four lineages of Posthodiplostomum were recorded from poeciliids (though not Poe. reticulata) and other cyprinodontiform fishes by Pérez-Ponce de León (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) in Central America.

The present results add to an evolving picture of metacercarial host-specificity in Posthodiplostomum. In the more intensively sequenced species of Posthodiplostomum, patterns of host specificity emerging from early surveys (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010) have generally been maintained. These patterns are consistent with subspecies Hoffman (Reference Hoffman1958) created based largely on the compatibility of cercariae with different fishes. In molecular surveys, metacercariae of Po. minimum have been recovered only from leuciscid hosts (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010; Komatsu et al., Reference Komatsu, Itoh and Ogawa2020; Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), and those of Po. centrarchi nearly exclusively from Lepomis spp., which mirrors the specificity of cercariae in Hoffman's (Reference Hoffman1958) experiments. Notably, except for 7 specimens from 3 fish that Boone et al. (Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018) suspected to be M. salmoides × Micropterus punctulatus hybrids, Po. centrarchi has not been recovered from species in the centrarchid genus Micropterus in modern sequencing surveys, and cercariae of Po. centrarchi were also incompatible with M. salmoides in Hoffman's (Reference Hoffman1958) experimental infections. In other words, what Hoffman (Reference Hoffman1958) and later authors have called the ‘centrarchid line’ does not infect all centrarchids. Instead, in molecular surveys, members of Micropterus commonly harbour Posthodiplostomum sp. 8. All of these nearly exclusive associations have remained consistent in sequencing surveys, despite the novel hosts that cercariae of Po. minimum, Posthodiplostomum sp. 8 and Po. centrarchi encounter in diverse and widespread habitats (present study; Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010, Reference Locke, Van Dam, Caffara, Pinto, López-Hernández and Blanar2018; Kvach et al., Reference Kvach, Jurajda, Bryjová, Trichkova, Ribeiro, Přikrylová and Ondračková2017; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Mutafchiev, Pankov and Georgiev2018; Cech et al., Reference Cech, Sándor, Molnár, Paulus, Papp, Preiszner, Vitál, Varga and Székely2020; Komatsu et al., Reference Komatsu, Itoh and Ogawa2020). Our data from Caribbean hosts and parasites not previously surveyed are thus consistent with both these particular patterns and the host specificity that generally prevails among this group of parasites. It is relevant to note that other than what is reported herein, no similar neascus have been observed in hundreds of additional fish, including all native species to the island and over a dozen of introduced species (Locke SA, unpublished data).

The present results thus suggest a narrow second-intermediate host use in 7 lineages of Posthodiplostomum in Puerto Rico that is consistent with most molecular surveys to date. In contrast, Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) recently reported 6 lineages of Posthodiplostomum, 4 infecting multiple families of fish throughout Central America. Unfortunately, a direct comparison of sequences with those of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) is impossible. One or more of the species encountered in Puerto Rico may be conspecific with lineages I–VI from Central America of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), particularly Po. macrocotyle, and Posthodiplostomum spp. 24, 25 and 26, some of which were found in host families (cichlids and poeciliids) also sampled by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022). While morphological comparisons do not support conspecificity, the differences observed (see Remarks) may be to some extent related to geographic (Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017) and host-associated (Palmieri, Reference Palmieri1975, Reference Palmieri1977a, Reference Palmieri1977b, Reference Palmieri1977c) morphological variation within species. If the same species of Posthodiplostomum have indeed been studied and sequenced in our study and throughout Central America by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), then differences in host range in the 2 studies could be attributed to the comparatively depauperate fish fauna of Puerto Rico. For example, Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) reported 3 lineages (I, II and IV) from families of fish [Leuciscidae (as Cyprinidae), Goodeidae, Profundulidae, Fundulidae] that are absent or uncommon in Puerto Rico, as well as in various poeciliids, which are represented in our collections by Poe. reticulata. In the present study, lineages I, II or IV of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) may have been restricted to a locally available poeciliid host (Poe. reticulata) because of the absence of other compatible host taxa on the island.

However, we consider that Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) probably underestimated the number of species represented in their sequence data, and that other interpretations of host specificity in their samples are possible. For example, levels of CO1 divergence within lineages III (8%) and IV (6%) reported by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) exceed those known within species of Posthodiplostomum [maxima of intraspecific CO1 divergence of 2.26% (Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010), 1.7% (Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017), 3.91% (Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018) and 3.8% (Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021)] and other digeneans (e.g. the suggested 5% cutoff of Vilas et al., Reference Vilas, Criscione and Blouin2005), including Diplostomum species in which hundreds of individuals were sequenced with geographically widespread sampling (maximum intraspecific CO1 K2P = 2.66% in Locke et al., Reference Locke, Al-Nasiri, Caffara, Drago, Kalbe, Lapierre, McLaughlin, Nie, Overstreet, Souza, Takemoto and Marcogliese2015). Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) also delineated most species based on ITS with incomplete support from CO1. For example, while the ITS sequences of lineage I were obtained from parasites from multiple fish families, CO1 was only available from a subset from poeciliids, meaning that the wide host range of lineage I is effectively based on ITS alone. This is problematic because ITS can vary little or not at all between recently separated species (Vilas et al., Reference Vilas, Criscione and Blouin2005; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Al-Nasiri, Caffara, Drago, Kalbe, Lapierre, McLaughlin, Nie, Overstreet, Souza, Takemoto and Marcogliese2015; Cribb et al., Reference Cribb, Bray, Justine, Reimer, Sasal, Shirakashi and Cutmore2022).

To some extent, the contrasting host-use patterns emerging from this study and that of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) will be clarified by determining which species of Posthodiplostomum are co-distributed in fish in both Central America and Puerto Rico (most pragmatically achievable by sequencing homologous CO1). The available data show that 3 of 7 species we found in Puerto Rico (Po. centrarchi, Posthodiplostomum spp. 8 and 23) were not encountered by Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022). However, regardless if species co-occur in both regions, we believe it to be unlikely that the host specificity of metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum differs fundamentally in the Caribbean and Middle America, and for this reason, we believe that 2 types of additional data are necessary to reconcile our results with those of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022). First, as most of the species of Posthodiplostomum encountered herein are only known from a limited study area, CO1-based records from additional samples in novel environments will allow assessment of metacercarial host specificity against the background of a different or richer host fauna. Second, we contend that the multi-family host range of several lineages in Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) remains to be verified, for example through sequencing CO1 in isolates of lineage I from non-poeciliid hosts. In addition, care is needed in interpreting host ranges of lineages in Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022) due to conflicts between the paper and GenBank records. For example, OK315743 and OK314903 appear to be sequences from the same individual worm (see Table 1 in Pérez-Ponce de León et al., Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), but these GenBank records list different hosts (Poecilia latipunctata and Herichthys labridens) and lineages (I and III).

Our prediction is that subsequent studies will reveal most species of Posthodiplostomum to have metacercariae restricted to a narrow range of hosts (e.g. a single family). This expectation is based on molecular surveys of metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum, which have revealed 3 generalists and 11 specialists. The generalists comprise Posthodiplostomum pricei, with CO1-based records of metacercariae in Fundulidae, Centrarchidae and Moronidae (Blasco-Costa and Locke, Reference Blasco-Costa and Locke2017); Posthodiplostomum cf. podicipitis, with CO1-based records in Leuciscidae and Catostomidae (Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021) and Posthodiplostomum lineage II, with CO1-based records in Leuciscidae and Goodeidae (Pérez-Ponce de León et al., Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022). In contrast, the CO1-based species delimitations of the following 11 species reveal single-family host ranges: Po. centrarchi, Po. minimum, Posthodiplostomum cf. anterovarium and Posthodiplostomum sp. 8 (sampled in multiple contexts in the present study, Locke et al., Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010, Reference Locke, Van Dam, Caffara, Pinto, López-Hernández and Blanar2018; Kvach et al., Reference Kvach, Jurajda, Bryjová, Trichkova, Ribeiro, Přikrylová and Ondračková2017; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Georgieva, Pankov, Kudlai, Kostadinova and Georgiev2017; Boone et al., Reference Boone, Laursen, Colombo, Meiners, Romani and Keeney2018; Stoyanov et al., Reference Stoyanov, Mutafchiev, Pankov and Georgiev2018; Cech et al., Reference Cech, Sándor, Molnár, Paulus, Papp, Preiszner, Vitál, Varga and Székely2020; Komatsu et al., Reference Komatsu, Itoh and Ogawa2020; Achatz et al., Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), and 7 species of Posthodiplostomum sampled in the St. Lawrence River [Posthodiplostomum spp. 5 and 7 in Locke et al. (Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010) and Posthodiplostomum spp. 10–14 of Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021) (=Ornithodiplostomum spp. 1–3, 4, 8 of Locke et al. (Reference Locke, McLaughlin, Dayanandan and Marcogliese2010)].

The modern world provides species of Posthodiplostomum with many opportunities to colonize newly encountered host taxa, by reshuffling host assemblages through changing climate (Marcogliese, Reference Marcogliese2001) and species introductions (Rahel, Reference Rahel, Gido and Jackson2010). In Puerto Rico, the accidental or intentional introduction of non-native fish species has occurred since the early 1900s (Neal et al., Reference Neal, Noble, Olmeda, Lilyestrom, Nickum, Mazik, Nickum and MacKinlay2004, cited in Neal et al., Reference Neal, Lilyestrom and Kwak2009). Forty-six freshwater fishes have been reported in the island, of which only 9 species are native (Rodríguez-Barreras et al., Reference Rodríguez-Barreras, Zapata-Arroyo, Falcón and Olmeda2020). Introduction of new host species can cause a decrease in abundance of native species through co-introduction of pathogens (reviewed by Daszak et al., Reference Daszak, Cunningham and Hyatt2000 and Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Smith, Torchin, Dobson, Kuris, Sax, Stachowicz and Gaines2005), although this has not been studied in Puerto Rico freshwater fish assemblages. Bunkley-Williams and Williams (Reference Bunkley-Williams and Williams1994) encountered varying infection levels of Posthodiplostomum-type neascus from freshwater fishes introduced to Puerto Rico, but found none in native fishes. These authors reported intensities of 1–2 metacercariae per host of Po. centrarchi (as Po. minimum) in Lepomis spp., of which 9 of 10 were infected. Only 1 of 33 Micropterus sp. was infected (presumably with Posthodiplostomum sp. 8). Few (2/8) guppies were infected, but intensity was high (8–10 metacercariae per host). In the present study, a similar infection intensity was observed in guppies, and overall infection levels were higher in introduced hosts than in the native D. monticola. No evidence was seen for ‘spill over’ of Posthodiplostomum between introduced and native fish hosts, nor for that matter were species of Posthodiplostomum shared among any host species. This stands in contrast to the recent discovery of a digenean native to the Indomalayan region, Transversotrema patialense, in introduced snails and both native and introduced fishes in the Quebrada de Oro, i.e. the same small stream studied here (Perales Macedo et al., Reference Perales Macedo, Díaz Pernett, Díaz González, Torres Nieves, Santos Flores, Díaz Lameiro and Locke2022).

Attempts to identify the first-intermediate hosts of any of the Posthodiplostomum species found in fish were unsuccessful, although the presence of metacercariae provides unequivocal evidence that the life cycle is completed locally. In 2722 individual snails, no diplostomid infections were observed in the single native gastropod species (Neritidae gen. sp.) nor the other species, all of which are introduced in Puerto Rico. Multiple species of Physa, such as Ph. anatina, Ph. gyrina, Ph. fontinalis and Ph. integra, have been reported to be suitable hosts for cercariae of Posthodiplostomum and Ornithodiplostomum species (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1958; Sankurathri and Holmes, Reference Sankurathri and Holmes1976; Radabaugh, Reference Radabaugh1980; Hendrickson, Reference Hendrickson1986). Among the snails collected, Physa acuta is therefore the most likely first-intermediate host of the Posthodiplostomum species observed in Poe. reticulata and D. monticola, in view of prior records of Posthodiplostomum and similar neascus-forming species in members of the Hygrophila such as Physidae and Planorbidae (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1960; Ostrowski de Núñez, Reference Ostrowski de Núñez1973; Velázquez-Urrieta and Pérez-Ponce de León, Reference Velázquez-Urrieta and Pérez-Ponce de León2021). The absence of infections in 747 Ph. acuta collected from the same localities as the infected fish is consistent with reported prevalences, which are particularly low in non-native populations of Ph. acuta (Ebbs et al., Reference Ebbs, Loker and Brant2018). Diplostomid infections were also absent from 1763 thiarids belonging to 2 species, and a small number of M. cornuarietis (Ampullariidae), which is unsurprising given the absence of prior reports of Posthodiplostomum in these snail families. However, the recent expansion of the genus Posthodiplostomum by Achatz et al. (Reference Achatz, Chermak, Martens, Pulis, Fecchio, Bell, Greiman, Cromwell, Brant, Kent and Tkach2021), along with the high number of species known only genetically, or in which snail hosts are unknown, suggests that new host–parasite combinations in Posthodiplostomum remain to be discovered, particularly for snails. Diplostomoids have been recorded from the thiarid species we sampled in their native range in Southeast Asia (Krailas et al., Reference Krailas, Namchote, Koonchornboon, Dechruksa and Boonmekam2014; Veeravechsukij et al., Reference Veeravechsukij, Namchote, Neiber, Glaubrecht and Krailas2018), but not in introduced populations. Nasir et al. (Reference Nasir, Hamana and Díaz1969) recorded a longifurcocercous cercariae in M. cornuarietis in its native range (Venezuela). However, the furcocercous cercariae recorded by Krailas et al. (Reference Krailas, Namchote, Koonchornboon, Dechruksa and Boonmekam2014), Veeravechsukij et al. (Reference Veeravechsukij, Namchote, Neiber, Glaubrecht and Krailas2018) and Nasir et al. (Reference Nasir, Hamana and Díaz1969) all possess well-developed ventral suckers and other characters that distinguish them from cercariae known from Posthodiplostomum (Blair, Reference Blair1977; Hendrickson, Reference Hendrickson1986; Ritossa et al., Reference Ritossa, Flores and Viozzi2013; López-Hernández et al., Reference López-Hernández, Locke, De Melo, Rabelo and Pinto2018).

Compared with previous records based on morphology (Bunkley-Williams and Williams, Reference Bunkley-Williams and Williams1994), the present molecular results constitute a substantial increase in species diversity, particularly given that our sampling effort was not especially intense: 58 infected guppies, 54 mountain mullet, 14 jaguar guapote and 6 from Micropterus spp. Clearly, this indicates that further studies, particularly with greater host species coverage, are likely to reveal additional species of Posthodiplostomum in the Caribbean. Remarkably, most species of Posthodiplostomum recovered herein were from non-native hosts, which typically harbour fewer species of parasites than native hosts (Torchin et al., Reference Torchin, Lafferty, Dobson, McKenzie and Kuris2003). Taken together with the findings of Pérez-Ponce de León et al. (Reference Pérez-Ponce de León, Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho and García-Varela2022), these results suggest a particularly fruitful area of further molecular prospecting in Posthodiplostomum will be in poeciliids and cichlids in their native ranges.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of Posthodiplostomum infecting Pa. managuensis and D. monticola. These results also suggest that non-native hosts in Puerto Rico (Pa. managuensis, Poe. reticulata, L. macrochirus, L. gibbosus, M. salmoides, M. dolomieu) have co-introduced diplostomid parasites into the local environment, or facilitated their establishment, although no evidence was observed for Posthodiplostomum species shared among native and introduced freshwater fishes on the island. The relatively small geographical area surveyed demonstrates that the diversity of this group of parasites in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean is potentially much higher.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182022001214.

Data availability

The newly generated sequences are deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers OP071160-225. Morphological vouchers of parasites and of host tissues were deposited in the Museum of Southwestern Biology (MSB:Para:33294-301, MSB:Host:24820-1).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Diana Perales Macedo, María Díaz Gonzalez and Jacob Lopez Cruz for assistance in the field and laboratory; to Florian B. Reyda, David J. Marcogliese and Robin M. Overstreet for providing samples, and to Benjamin van Ee, Carlos J. Santos Flores, and 3 anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on early versions of the manuscript.

Author contributions

S. A. L. and S. C. D. P. conceived, designed and conducted the study. S. C. D. P. performed statistical and phylogenetic analyses. S. A. L., S. C. D. P. and S. V. B. wrote and revised the article.

Financial support

This research was funded mainly by the National Science Foundation (DEB award 1845021) with early support from the Puerto Rico Science, Technology and Research Trust (PRSTRT grant 2016-00080). S. C. D. P. was supported by the COVID-19 Science Communication and Living Expenses Grant from the PRSTRT in 2021.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This study was conducted with approval of the UPRM IACUC (OLAW assurance D20-01098).