INTRODUCTION

Microsporidia are a group of unicellular eukaryotes, all living as obligate intracellular parasites and forming small spores able to persist in the environment (Wittner and Weiss, 1999). These organisms infect many animals and several species are responsible for opportunistic diseases in immunocompromised humans (Didier, 2005). The initiation of microsporidian invasion requires the extrusion at the spore apex of a very long and coiled structure, the polar tube, through which the sporoplasm is pushed to enter into a potential host cell (Franzen, 2004). After sporoplasm internalization, the development of the parasite comprises a proliferative phase or merogony (multiplication of meronts) and a differentiation phase or sporogony that starts with the conversion of meronts into sporonts, marked by the formation of an electron-dense cell coat. Sporonts then divide to give sporoblasts that undergo spore differentiation, involving the biogenesis of a thick bipartite wall (outer part: exospore; inner part: endospore) and of a characteristic set of cytoplasmic structures (polar tube, anchoring disk, polaroplast, posterior vacuole) commonly named the invasion apparatus. In Encephalitozoon species, all steps of the intracellular cycle occur inside a specialized vacuole of the host cell (parasitophorous vacuole). Spores are released in close environment after host cell lysis.

The programme of differential gene expression related to microsporidian spore differentiation is still poorly known. The best characterized proteins of Encephalitozoon spores are PTP1, PTP2 and PTP3 located to the polar tube (Delbac et al. 1998b, 2001; Keohane et al. 1998; Peuvel et al. 2000, 2002) and SWP1 assigned to the exospore (Böhne et al. 2000; Hayman et al. 2001). A long-duration IgG antibody response to SWP1 has been observed in an immunocompetent individual that was infected with Encephalitozoon cuniculi (van Gool et al. 2004). A transcriptional control of the synthesis of such proteins has been inferred from reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) assays with RNA from infected mammalian cell cultures (Böhne et al. 2000; Hayman et al. 2001; Peuvel et al. 2002). However, it should be stressed that the timing of mRNA content variations after contact of spores with tissue cultures cannot be strictly applied to the succession of cell stages characterizing the progression of Encephalitozoon development. One major reason is that merogonic and sporogonic stages co-exist in parasitophorous vacuoles, their enlargement involving both multiplication of meronts close to the vacuole membrane and multi-step formation of spores inside the remaining vacuolar space (Sprague and Vernick, 1971; Shadduck, Bendele and Robinson, 1978). Moreover, there is no precise information about the duration of individual developmental steps.

A recent study in our laboratory has led to the molecular characterization of 2 novel E. cuniculi wall proteins (EnP1 and EnP2) that were targeted to the endospore (Peuvel-Fanget et al. 2006). A very high representation of enp1 mRNA in a cDNA library was suggestive of a highly abundant mRNA in E. cuniculi cells. This encouraged us to test a protocol of in situ hybridization (ISH) on ultrathin frozen sections, as an attempt to better correlate mRNA fluctuations with transmission electron microscopy (TEM)-identified microsporidian stages. In this study, the use of immunocytochemical and ISH techniques coupled with cryo-ultramicrotomy allowed a comparison of exospore SWP1 and endospore EnP1 in terms of protein deposition and mRNA level changes during parasite development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures

Encephalitozoon cuniculi was propagated in culture with Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) or Human Foreskin Fibroblast (HFF) cells in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine, at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Electron microscopy

Infected MDCK or HFF cells were fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0·1% glutaraldehyde in 0·1 M phosphate buffer pH 7·4, scrapped off, concentrated by centrifugation at 1700 g for 15 min and finally rinsed in the same buffer for 30 min. In the cryosectioning method (Tokuyasu, 1973), cells were infiltrated with 2·3 M sucrose for 16 h, then frozen in slush nitrogen at 10−6 Torr and stored in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin frozen sections (85–100 nm in thickness) were obtained using a dry sectioning device at −110 °C with an UltracutS Leica ultramicrotome fitted with the low-temperature sectioning system FC4. Sections were mounted on collodion-coated nickel grids, stored in 2·3 M sucrose at 4 °C, and then used for either protein immunolocalization or RNA hybridization. For comparison, infected cells were also embedded in a hydrophilic resin. After dehydration, cells were infiltrated in 50% ethanol-50% Unicryl™ resin (British Bio-Cell International) overnight at 4 °C. The polymerization was performed for 3 days in pure Unicryl™ over UV light at −20 °C. The sections were cut at 85 nm thickness. All sections were viewed at 80 keV under a 1200EX Jeol transmission electron microscope.

Protein immunocytochemistry

The monoclonal antibody Mab 11A1 reacting specifically with SWP1, was kindly provided by Dr W. Böhne (Department of Bacteriology, University of Göttingen, Germany). Mouse polyclonal antibodies were previously raised against EnP1 (anti-01_0820 antisera) in our laboratory by Drs I. Peuvel-Fanget and F. Delbac. Specificity was checked by Western blotting. After 30 min of PBS washing, ultrathin frozen sections were blocked for 30 min with 1% ovalbumin-PBS, incubated for 2 h with primary mouse antibodies, diluted at 1[ratio ]100 in PBS, washed and incubated for 1 h with a 1[ratio ]100 dilution of a goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with 5 nm colloidal gold particles (Sigma). Grids were washed then stained in 0·8% uranyl acetate-1·6% methylcellulose before TEM observation. Controls were carried out either with pre-immune sera or without primary antibody.

Oligonucleotide probes

From the complete genome sequence of E. cuniculi (Katinka et al. 2001), oligonucleotide sequences (22–25 bases) were designed for the targeted mRNAs, using bioinformatic tools associated with an ACeDB database in our laboratory. The primers used for ISH were 5′-CCGGCTCGATGCACACTTCGGAGC-3′ and 5′-CATGGTCGTTCCAGTAGAGCACG-3′ for enp1 (coding sequence ECU01_0820, GenBank Accession number CAD24952), 5′-GCCTGATCCGCTTCCGCTTGATCC-3′ and 5′-CCGCTTCCATCTGATCCGCTTCC-3′ for swp1 (coding sequence ECU10_1660, GenBank Accession number CAD25887). Five oligonucleotides specific for 5·8S and 23S rRNA sequences were also determined. No potential hybridization with other E. cuniculi RNAs was predicted, even when authorizing 5 mismatches. Biotinylated oligonucleotides probes were synthesized by solid-phase phosphoramidite chemistry and labelled by tailing 3′ ends with biotin (Eurogentec).

RNA in situ hybridization

An RNA hybridization technique for cryosections was developed on the basis of the various protocols described by Morel and Cavalier (2000). Sections from either Unicryl™-embedded or frozen material were washed in 2×SSC (Standard Sodium Citrate) buffer and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in the hybridization buffer without the probe. Hybridization was performed for 3 h at 37 °C in a buffer containing 30% deionized formamide, 4×SSC, 2×Denhardt's solution (0·04% BSA, 0·04% Ficoll 400, 0·04% polyvinylpyrolidone 360) and 0·1–1 μM of each oligonucleotide. Grids were washed for 10 min in 4X SSC and 3 times for 10 min each in 2×SSC, then fixed for 5 min in 4% paraformaldehyde-2×SSC. After washing in 2×SSC for 30 min, grids were incubated with 2% ovalbumin in 0·1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7·4, for 30 min. Hybridized biotin probes were reacted for 1 h with a goat anti-biotin antibody (Sigma) diluted to 1[ratio ]50 with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7·6, 300 mM NaCl, and rinsed for 30 min in the same buffer. Grids were subsequently treated for 1 h with a 1[ratio ]50 dilution of rabbit anti-goat IgG 5 nm gold conjugate (Sigma) in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7·6, 300 mM NaCl, washed twice for 10 min each in the same buffer then in 2×SSC. After a final rinse for 10 min in distilled water, cryosections were contrasted with 0·8% uranyl acetate-1·6% methylcellulose. Resin sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate-50% ethanol. Different controls were performed: (a) hybridization with oligonucleotides specific to E. cuniculi (5·8S and 23S) rRNA as a positive control, (b) omission of the probes, (c) hybridization with a labelled sense probe, (d) omission of the different antibodies. Host cell regions that were negative for parasite mRNA expression served as internal control. The largest cross-sections of parasite cells (more than 1·4 μm2) were selected for counting gold particles (8–12 cells per stage sample). Areas were determined after cutting cell profiles on electron micrograph hard copies and weighting.

RESULTS

Structural preservation of cryo-sectioned Encephalitozoon cuniculi cells

Hydrophilic resin-embedding methods have previously been used for investigating the localization of microsporidial antigenic proteins such as Encephalitozoon PTPs (Keohane et al. 1998; Delbac et al. 2001) and SWPs (Böhne et al. 2000; Hayman et al. 2001). The ultrastructural preservation of membrane systems was generally poor, compared with that observed in standard conditions of epoxy resin embedding. Cryo-ultramicrotomy is known to avoid most preparation artifacts even if some local distortions may persist. In addition, frozen sections offer a high sensitivity for hybridization experiments. A cryosectioning method was therefore applied to samples of E. cuniculi-infected cell cultures, using saccharose as cryoprotectant, slush nitrogen for freezing, very low temperatures for cutting and methylcellulose as a final embedding agent.

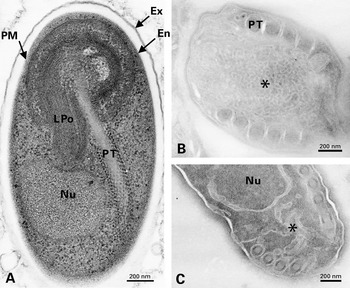

A section of an E. cuniculi mature spore after usual epoxy resin embedding is shown in Fig. 1A. Some parts of the invasion apparatus could be identified and the 2 major layers of the spore wall were easily distinguished on the basis of both thickness and staining intensity. Numerous ribosomes accounted for the electron-dense character of the cytoplasm. The images from ultrathin frozen sections (Figs 1B–4C) were of particular interest for a better discrimination of meronts, sporonts and early sporoblasts when referring to some changes in cell shape and complexity of cell surface. Cisternae of the endoplasmic reticulum were clearly visible, which was rarely the case on Unicryl™ sections. Vesicles of various sizes could be mainly related to the non-dictyosomal Golgi apparatus and steps of biogenesis of the polar tube and polaroplast in sporoblasts. The close junction between the meront plasma membrane and the parasitophorous vacuole membrane was also preserved (Figs 3B, C and 4A). This junction at the host-parasite interface is possibly permeable to allow an extensive transport of molecules required for meront growth.

Fig. 1. (A) Longitudinal section of an Encephalitozoon cuniculi spore after standard epoxy resin embedding. Two spore wall layers are distinguished: the thin electron-dense exospore (Ex) and the thick electron-translucent endospore (En) closer to the plasma membrane (PM). The nucleus (Nu), the lamellar part of the polaroplast (LPo) and the straight anterior part of the polar tube (PT) surrounded by numerous ribosomes are visible. (B-C) Ultrathin frozen sections of E. cuniculi sporoblasts (control experiment without primary antibody for protein immunolocalization). The formation of polar tube (PT) coils involves the fusion of numerous tubulovesicular elements and a close association with the cortical region.

Immunolocalization of SWP1 and EnP1 proteins

The precursors of E. cuniculi SWP1 and EnP1 proteins, with a cleavable signal peptide, were encoded by single-copy genes on 2 different chromosomes (ECU10_1660 on chromosome X for SWP1; ECU01_0820 on chromosome I for EnP1). No homologue was found in non-microsporidian organisms. The apparent molecular sizes of mature proteins deduced from SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were 51 kDa for SWP1 (Böhne et al. 2000) and 40 kDa for EnP1 (Peuvel-Fanget et al. 2006), close to the predicted sizes. The localization of EnP1 in the inner layer (endospore) of the E. cuniculi spore wall has been demonstrated by TEM immunocytochemistry on Unicryl™ sections (Peuvel-Fanget et al. 2006). In this study, to obtain images of antigen localization that could be more easily correlated with those of mRNA localization in similar E. cuniculi cell stages, cryosections were treated with anti-SWP1 and anti-EnP1 antibodies. Negative controls are illustrated in Fig. 1B and C.

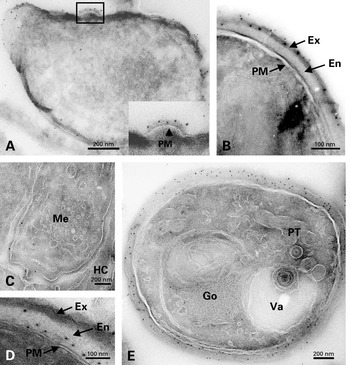

No significant gold labelling with anti-SWP1 antibody was detected in typical meronts (not shown). The first sign of SWP1 localization was represented by restricted areas of the corrugated cell surface (‘lamellar patches’) characteristic of the meront-sporont transitional stage (Fig. 2A). As expected, gold particles were distributed over the whole coat of sporonts to become specifically associated with the outer wall layer of late sporoblasts and spores (Fig. 2B). In sections treated with anti-EnP1 antibody, meronts exhibited regularly a slight labelling of the cytoplasm and plasma membrane (Fig. 2C), suggesting that EnP1 begins to be synthesized very early in merogony. All sporogonic stages were strongly reactive. Gold particles were preferentially located throughout the wall layer that strongly increases in thickness during spore differentiation and will give the endospore (Fig. 2D, E). Considering this thickening, a nearly continuous deposition of EnP1 likely occurs in sporoblasts. This is also supported by the persistence of a slight cytoplasmic labelling that may reflect the continuation of synthesis and transport processes. The number of gold particles associated with endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi vesicles was generally low, suggesting a high rate of intracellular transport of these wall proteins.

Fig. 2. (A–B) Immunolocalization of SWP1 on cryosections of Encephalitozoon cuniculi cells. Gold labelling can be seen on lamellar patches apposed to the plasma membrane in a developing sporont and on the outer wall layer in a late sporoblast. (C–E) Immunolocalization of EnP1 on cryosections of E. cuniculi cells. (C) Slight reactivity to anti-EnP1 of the cell surface of a meront (Me) lying at the periphery of the parasitophorous vacuole. HC, host cell. (D) Labelling of the thickened cell coat in a spore. (E) In a late sporoblast containing typical polar tube (PT) elements, gold particles are distributed throughout the endospore. Go, Golgi vesicles. Va, vacuole.

Detection of swp1 and enp1 mRNAs by in situ hybridization (ISH)

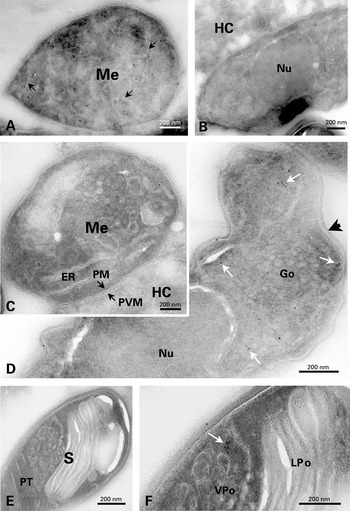

In preliminary experiments, the TEM ISH technique was used for detecting swp1 mRNA in sections of Unicryl™-embedded E. cuniculi cells, in spite of a rather mediocre ultrastructural preservation. Hybridization signals were very rare, casting doubt on their specificity. Additional tests were done with probes for 2 other mRNAs (enp2 for another endospore protein, ptp1 for a polar tube protein) or with another hydrophilic resin (LR White, London Resin Company, Berkshire, UK). No convincing data were obtained. Further ISH experiments were carried out on ultrathin frozen sections and initially applied to the detection of abundant ribosomal RNAs (5·8S and 23S rRNAs). Hybridization signals were observed in all E. cuniculi developmental stages, as shown in Fig. 3A for a meront and in Fig. 3B for a sporont. The best results were obtained with a 0·1 μM probe concentration, using different rRNA probes incubated for 3 h in the hybridization buffer and paraformaldehyde for hybrid stabilization. There was no cross-reactivity with host cell rRNAs.

Fig. 3. In situ hybridizations on cryosections of Encephalitozoon cuniculi cells. (A–B) Hybridization with rRNA probes. Cytoplasmic labelling in meront (A) and sporont (B) stages. Arrows indicate some elements of endoplasmic reticulum. No gold labelling is observed on the host cell (HC). (C–F) swp1 mRNA hybridization. (C) Meront (Me) with a very faint cytoplasmic labelling. Note the close junction between the parasite plasma membrane (PM) and the parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM). ER, endoplasmic reticulum. HC, host cell. (D) Expression of swp1 mRNA in a sporont. White arrows indicate some individual or clustered gold particles. Black arrow shows the typical SWP1-containing electron-dense coat. Go, Golgi vesicles. Nu, nucleus. (E) Reduced labelling in a mature spore (S). Polar tube (PT) coils are seen in the posterior region of the spore. (F) Enlarged part of (E), centered on a small cluster of gold particles (arrow). LPo, lamellar polaroplast. VPo, vesicular polaroplast.

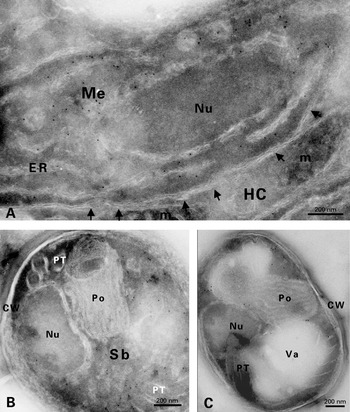

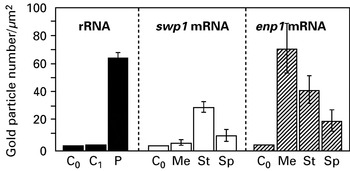

Cryosections were found to be also favourable to the detection of swp1 and enp1 mRNAs. The specificity of the reaction was confirmed by the absence of signal in controls without either probe or primary antibody, as well as in those with a complementary or antisense probe. With regard to swp1 mRNA, only a few gold particles were associated with meront cytoplasm (Fig. 3C). Gold labelling clearly increased in the cytoplasm of sporonts (Fig. 3D) and early sporoblasts. A low level in mature spores (Fig. 3E, F) was suggestive of a decrease during late sporogony. Contrastingly, hybridization signals for enp1 mRNA were abundantly detected in meronts (Fig. 4A). This mRNA was also represented in sporoblasts, including stages that were deeply engaged in the assembly of the polar tube and polaroplast (Fig. 4B). A slight labelling of mature spores (Fig. 4C) may be significant because the background was low and the gold particles were located on electron-dense cytoplasmic zones known to be rich in ribosomes. In an attempt to quantify the mRNA level changes during E. cuniculi development, the number of gold particles was counted on large cross-sections of parasite cells then calculated for a same area unit. Significant differences between the considered cell stages were found for each mRNA (Fig. 5). Meronts display the lowest value for swp1 mRNA and the highest one for enp1 mRNA. The sporont-sporoblast class is marked by a 5-fold increase of swp1 mRNA level and a decrease (~60%) of enp1 mRNA level. A subsequent reduction occurs in spores for both mRNAs. As the different probes may not have identical hybridization efficiencies, the comparison of the values obtained for swp1 and enp1 in a same cell stage may be not valid. However, it seems reasonable to think that enp1 mRNA is globally more abundant or more stable than swp1 mRNA because of a very significant expression during a larger part of the parasite cycle as of a higher frequency in cDNA library and a higher relative amount deduced from RT-PCR experiments at different post-infection times (Peuvel-Fanget et al. 2006).

Fig. 4. In situ hybridizations on cryosections of Encephalitozoon cuniculi cells for the detection of enp1 mRNA. (A) High abundance of enp1 mRNA in a meront (Me). Most gold particles are seen close to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) cisternae. Arrowheads show the parasitophorous vacuole membrane adjacent to the meront plasma membrane. Mitochondria (m) of the host cell (HC) are frequently found near the junction with the parasite cell. Nu, nucleus. (B) In a sporoblast (Sb), hybridization signals are associated with ribosome-rich cytoplasmic areas extending between precursor structures of the polar tube (PT) and polaroplast (Po). CW, cell wall. Nu, nucleus. (C) In the sporal stage, hybridization signals are rare (arrows) but specifically restricted to ribosome-containing regions. Note that polar tube (PT) coils are positioned around a large vacuole (Va) in the posterior region of the spore. CW, cell wall. Nu, nucleus. Po, polaroplast.

Fig. 5. Levels of mRNAs encoding SWP1 and EnP1 in Encephalitozoon cuniculi, as estimated by the labelling intensities after hybridization on cryosections of different cell stages (Me, meronts. St, sporonts-sporoblasts. Sp, spores). The level of rRNA (5·8S+23S) calculated for all parasite stages is also shown (P). C0 and C1 represent controls without oligonucleotide and with a sense probe, respectively. Labelling intensity is expressed as the mean number of gold particles per μm2 of cell area. Vertical bars represent standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Cryo-ultramicrotomy has been used successfully to localize 2 antigenic proteins and corresponding mRNAs in cell stages of the microsporidian Encephalitozoon cuniculi. From a technical point of view, cryosectioning offered a good compromise between cytological preservation and labelling specificity and intensity. In particular, the internal membranes of meronts and early differentiating stages were better preserved than after embedding in hydrophilic resins. Ultrathin frozen sections of 3 microsporidian species belonging to different genera (Antonospora locustae, Brachiola algerae and Nosema bombycis) also gave us high quality images (data not shown), which is encouraging for further comparative studies. As far as we know, only one ultracytochemical study using cryosections has been reported previously for microsporidia. A mitochondrial HSP70 homologue was shown to be localized inside small double-membrane bounded vesicles of the meronts and sporonts of Trachipleistophora hominis, providing first experimental evidence of relict mitochondrion-derived organelles (mitosomes) in microsporidia (Williams et al. 2002). Likewise, mitosomes were identified in the diplomonad Giardia intestinalis after treatment of frozen sections with antibodies raised against 2 mitochondrial markers (Tovar et al. 2003). Cryosectioning has therefore proven to be useful in the visualization of cryptic organelles in unicellular parasites.

The SWP1 and EnP1 proteins here considered were good molecular markers for the two major layers of the Encephalitozoon spore. The exospore shares an electron-dense appearance with the coat of sporonts, suggesting that its biogenesis is initiated during early sporogony. Two exospore glycoproteins (SWP1 and SWP2) have been identified in E. intestinalis and immunolocalization experiments have shown that SWP1 is initially deposited on the surface of early sporonts while SWP2 is first detected on fully formed sporonts (Hayman et al. 2001). In the case of the unique SWP1 protein in E. cuniculi, the first stages to have a SWP1-positive cell surface were also shown to be developing sporonts (Böhne et al. 2000). This has been verified in our study with frozen sections. The patchy labelling pattern fits with the scalloped appearance of transitional stages from meront to sporont. We assume that SWP1 deposition contributes to the relaxation of the attachment of meronts to the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) membrane. Curiously, some ‘tubular’ appendages reacting with anti-SWP1 were claimed to extend from spores to the PV lumen in E. cuniculi, leading to the hypothesis of a release of SWP1 from mature spores (Böhne et al. 2000). It is known that E. intestinalis, not E. cuniculi, induces the formation of a septated PV characterized by a network of fibrous septa enclosing individual spores (Cali, Kotler and Orenstein, 1993). The contribution of exospore proteins to septa formation in E. intestinalis is supported by the strong reactivity of these septa with an antibody recognizing a 125 kDa exospore protein that remains to be analysed at the sequence level (Prigneau et al. 2000). In contrast, a study on the localization of both SWP1 and SWP2 in E. intestinalis did not provide evidence for reactive septa and ‘tubular’ projections (Hayman et al. 2001). We also failed to identify SWP1-containing elements within the E. cuniculi PV lumen. Additional investigations are therefore required to determine whether SWP1 is really released in the PV, or not.

The endospore is electron lucent under standard staining conditions and extends between the plasma membrane and the exospore. Chitin is the major endospore component and has been visualized as a complex network of thick fibrils in deep-etched preparations (Bigliardi et al. 1996). During microsporidian development, the intercalation of poorly contrasted material is initiated in newly formed sporoblasts then the corresponding layer increases in thickness until the spore is completely mature. On the basis of morphological criteria, endospore formation would therefore span all the period required for the differentiation of sporoblasts into spores. The presence of specific proteins in the endospore has been first documented by TEM immunocytochemistry in 2 Encephalitozoon species (Delbac et al. 1998a; Prigneau et al. 2000). This study has revealed a very early deposition of EnP1 on E. cuniculi meront stages without cytological sign of meront-sporont transition. It is somewhat surprising that the onset of the migration of EnP1 to the parasite surface precedes that of SWP1, given that the EnP1-containing layer will occupy an inner position in the spore wall. For the same species, it has been demonstrated that a chitin deacetylase-like protein is initially deposited onto developing sporonts with the same patchy pattern as SWP1 but remains distributed at a very close proximity of the plasma membrane in later sporogonic stages including mature spores (Brosson et al. 2005). Chitin deacetylase catalyses the conversion of chitin into chitosan, a more resistant polymer that may account for the rigidity of the microsporidian spore wall. Whether chitin deposition begins in very early sporogony and whether the placement of EnP1 throughout the inner wall layer depends on specific interactions with chitin microfibrils are open questions. Various chitin-binding proteins share a common structural motif including a conserved core of 4 intramolecular disulfide bonds, known as the chitin-binding domain type-1 (Wright, Sandrasegaram and Wright, 1991). Such a domain is not predicted in the EnP1 sequence. However, EnP1 is rich in cysteine residues (23 residues; 6·4%) and several disulfide bonds are predicted with a very high score using the web server DiANNA (http://clavius.bc.edu/~clotelab/DiANNA). A future search for EnP1 homologues in other microsporidia should enable determination of whether a conserved region retains cysteine residues involved in the potential disulfide linkages.

RT-PCR assays have previously been used to study the expression of swp1 and swp2 mRNAs during Encephalitozoon development (Böhne et al. 2000; Hayman et al. 2001). The experimental approach consisted of the ‘synchronization’ of the infection by incubation of host cell cultures with parasite spores for a short period, and the harvesting of infected host cells at different times to perform successively total RNA isolation, reverse transcription and PCR amplification. Compared with beta-tubulin mRNA, the levels of swp mRNAs increased strongly between 24 and 72 h, supporting an up-regulation at the transcriptional level. This increase correlates with the accumulation of parasite cells inside numerous PVs but the relation with peculiar developmental stages remains unclear. All of these stages are indeed present in large PVs. Therefore, a TEM ISH approach was of interest to investigate mRNA expression in microsporidia for which no protocol of isolation of merogonic stages exists. One example of successful application of TEM ISH to the analysis of the cycle of an intracellular parasite is provided by the report of a stage-specific expression of the ATP/ADP translocator mRNA in Plasmodium falciparum (Jambou, Hatin and Jaureguiberry, 1995). Here, we have shown that enp1 and swp1 transcripts are especially abundant in meront and sporont-sporoblast stages, respectively. This fits with the immunocytochemical detection of EnP1 on meronts and SWP1 on developing sporonts. ISH evidence for enp1 mRNA in meronts also correlates with the significant level of this mRNA that was detected by RT-PCR in samples of cultures taken at early post-infection times (Peuvel-Fanget et al. 2006). The enp1 mRNA level was still relatively high in sporoblasts, indicating that the accumulation of EnP1 within the future endospore requires the continuation of the transcriptional activity during at least early sporogenesis. Whatever the studied transcript, the intensity of hybridization signals was weak in fully mature spores, which is consistent with the view that these non-dividing cells would be poorly active in transcription. Obviously, the regulation of the expression of spore wall proteins may not depend exclusively on mRNA synthesis.

Much remains to be studied to understand the molecular complexity of the microsporidian spore wall and the dynamics of the secretion of its protein and carbohydrate components. The glycosylated status of SWPs is supported by lectin binding data (Böhne et al. 2000; Hayman et al. 2001), but the hypothesis of an N-linked oligosaccharide needs in-depth investigations. Indeed, genes homologous to those specifically required for protein N-glycosylation are not found in the genome of E. cuniculi and only O-mannosylation has been predicted (Katinka et al. 2001; Vivarès and Méténier, 2004). A major polar tube protein (PTP1) in E. hellem would be modified by O-linked mannosylation (Xu et al. 2004). Experiments are in progress to better characterize carbohydrate chains and glycoproteins in E. cuniculi. Finally, the availability of the E. cuniculi genome sequence authorizes the application of ISH on ultrathin frozen sections to numerous gene products. Recent proteomic approaches have revealed that various proteins of unknown function are expressed in the E. cuniculi sporal stage (Texier et al. 2005). Further use of corresponding sequences for ISH may be expected to provide significant advances in the knowledge of developmental expression of mRNAs related to that of novel microsporidia-specific proteins.

The authors are gratefully indebted to Dr W. Böhne for the gift of anti-SWP1 monoclonal antibodies. We also thank Dr I. Peuvel-Fanget for providing anti-EnP1 polyclonal antibodies and a copy of the manuscript reporting the identification of two endospore proteins.