INTRODUCTION

The Thelastomatoidea (Nematoda: Oxyurida) are pinworms found in the hindgut of terrestrial arthropods (Hominick and Davey, Reference Hominick and Davey1973; Connor and Adamson, Reference Connor and Adamson1998; Adamson and Noble, Reference Adamson and Noble1992, Reference Adamson and Noble1993). Although there have been many taxonomic studies of the Thelastomatoidea, there has been only one that has examined thelastomatoid biogeography (Jarry, Reference Jarry1964) and only two examining levels of host-specificity (Adamson, Reference Adamson1989; Jex et al. Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a). Jarry (Reference Jarry1964) provided distribution maps for 16 species from several species of millipedes, beetles and cockroaches from localities in Europe. Adamson (Reference Adamson1989) inferred levels of thelastomatoid specificity from host-parasite records in the literature but undertook no direct investigation. He concluded that there appeared to be some support, based on these records, for a high family level specificity for thelastomatoids from the families Hystrignathidae, Protrelloididae, Psuedonymidae and Travassosinematidae, but not for the largest family, Thelastomatidae (Adamson, Reference Adamson1989). Adamson (Reference Adamson1989) could find no evidence to support the hypothesis that the Thelastomatidae is a monophyletic lineage and suggested that paraphyly within this family may be largely responsible for obscuring any higher levels of host specificity. Jex et al. (Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a) examined the sharing of thelastomatoids across ecological and taxonomic divides between log-dwelling and leaf litter-dwelling arthropods. These authors suggested that thelastomatoid sharing was largely driven by host ecology not host taxonomy (Jex et al. Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a). However, no study has comprehensively examined the biogeography of an entire thelastomatoid system spanning all species of a host subfamily across its entire geographical range. Thus, there is essentially no knowledge of the patterns of distribution of thelastomatoids of cockroaches across broad systems and between closely related host species.

Many studies have examined the role of co-evolutionary descent in structuring patterns in specificity and distribution of nematodes in a variety of other host-parasite systems (Brooks and Glen, Reference Brooks and Glen1982; Adamson, Reference Adamson1989; Hoberg and Lichtenfels, Reference Hoberg and Lichtenfels1994; Sorci et al. Reference Sorci, Morand and Hugot1997; Hugot, Reference Hugot1999; Hugot et al. Reference Hugot, Gonzalez and Denys2001). Within the Oxyurida, there is perhaps no better example of coevolutionary speciation than has been documented for pinworms parasitizing primates (Brooks and Glen, Reference Brooks and Glen1982; Hugot et al. Reference Hugot, Gardner and Morand1996; Sorci et al. Reference Sorci, Morand and Hugot1997; Hugot, Reference Hugot1998, Reference Hugot1999). Cameron (1921) hypothesized that pinworms parasitizing primates “had evolved with the host” but that “evolution of the parasite is slower than that of the primate”, such that “one [pinworm] species restricts itself to one genus of host rather than to one species”. Subsequent studies have suggested that speciation within pinworm guilds in primates is largely attributable to coevolutionary processes (Brooks and Glen, Reference Brooks and Glen1982; Hugot et al. Reference Hugot, Gardner and Morand1996; Sorci et al. Reference Sorci, Morand and Hugot1997; Hugot, Reference Hugot1998, Reference Hugot1999). No study has examined the role of co-evolution in shaping the patterns of distribution and association in pinworms within arthropods.

In the present study, we examine the thelastomatoid fauna of 2 closely related cockroach subfamilies found in Australia. The Panesthiinae and Geoscapheinae are sister cockroach subfamilies in the Blaberidae (Roth, Reference Roth1977; Rugg and Rose, Reference Rugg and Rose1991). The panesthiines are log-burrowing, wood-feeding cockroaches, distributed throughout Australia and parts of Asia (Roth, Reference Roth1977, Reference Roth1982; Maekawa et al. Reference Maekawa, Lo, Rose and Matsumoto2003). In total, the Panesthiinae is comprised of approximately 250 species in 9 genera: 12 panesthiine species are found in Australia, 11 Panesthia and 1 Ancaudellia (Roth, Reference Roth1977). The geoscapheines are soil-burrowing, leaf litter-feeding cockroaches found only in Australia (Roth, Reference Roth1977; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Rugg and Rose1994). There are 20 described species of Geoscapheinae from 4 genera, Geoscapheus (6 species), Neogeoscapheus (3 species), Macropanesthia (9 species) and Parapanesthia (2 species) (Roth, Reference Roth1977; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Rugg and Rose1994).

Twenty-one thelastomatoid species, from 20 genera belonging to 2 families have been reported from 5 species of Australian burrowing cockroach, Panesthia cribrata, P. tryoni tryoni, Geoscapheus dilatatus, Macropanesthia rhinoceros and M. rothi (see Cobb, Reference Cobb1920; Chitwood, Reference Chitwood1932; Jex et al. Reference Jex, Cribb and Schneider2004, Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2005, Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2006b, Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribbc). In this study, we report the thelastomatoid fauna of all 24 known species of Geoscapheinae (4 undescribed), and 12 of the 13 known species of Panesthiinae (1 undescribed) from across most of their known geographical range in Australia. We examine 5 specific questions in relation to the data obtained. (1) Is the thelastomatoid fauna of Australian burrowing cockroaches distributed homogeneously or heterogeneously? (2) Do the thelastomatoids reported here have high or low specificity and broad or narrow geographical ranges? (3) Is there a correlation between host specificity and geographical range? (4) To what extent are thelastomatoid species shared between geoscapheine and panesthiine cockroaches; is there a system of high guild similarity, potentially explained by their close relationship, or a system of low similarity, potentially explained by ecological disparity? (5) Are the patterns of association between host and parasite consistent with one of co-evolutionary descent, as has been documented for the pinworms of primates?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Geoscapheine and panesthiine individuals were collected over a period of about 20 years, to 2005, from soil burrows and decaying logs throughout their range in Australia. The cockroaches were killed and preserved in 70% ethanol until dissection during 2002–2005. All cockroach specimens were identified to species according to Roth (Reference Roth1977) and Walker et al. (Reference Walker, Rugg and Rose1994) by one of us (H.A.R.).

A transverse incision was made along the posterior end of the abdomen. The hindgut was then teased out into 0·85% saline and severed at the point just anterior to the origin of the Malphigian tubules. The excised hindgut was dissected, and all nematodes found were extracted and preserved in fresh 70% ethanol.

All nematodes were identified using a morphological character database compiled from the literature as outlined by Jex et al. (Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2005). All of the species reported here have been treated systematically, except for 4 undescribed species: 3 species from Panesthia cribrata from Eumundi and 1 species from Panesthia tryoni tryoni from the Lamington National Park (Jex et al. Reference Jex, Cribb and Schneider2004, Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2005, Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2006b). These specimens, while sufficient to allow their differentiation from the other thelastomatoid species identified here, were not of suitable quality to allow formal descriptions.

Species richness estimates were calculated using the software package EstimateS v.7.0 (available at http://viceroy.eeb.uconn.edu/estimates). Although this software package provides many species richness estimators, only Bootstrap (Smith and van Belle, Reference Smith and van Belle1984), Chao2 (Chao, Reference Chao1987) and Jack1 (Burnham and Overton, Reference Burnham and Overton1978, Reference Burnham and Overton1979; Heltshe and Forrester, Reference Heltshe and Forrester1983; Smith and van Belle, Reference Smith and van Belle1984) were used as recommended by Poulin (Reference Poulin1998) and Walther and Morand (Reference Walther and Morand1998). Estimation values were calculated over 1000 runs, using a randomized dataset order for each run. Distribution maps were created using Biolink v.2.0 (available at http://www.biolink.csiro.au).

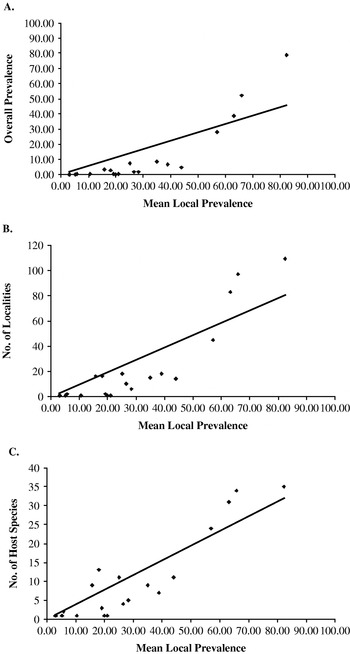

XY scatterplots were generated, comparing mean local prevalence levels for each thelastomatoid species with levels of regional dominance. Local prevalence, was defined as the prevalence of infection for each thelastomatoid species in each host species at each locality for which 5 or more host specimens were examined. Mean local prevalence was calculated as the mean of all local prevalence values for an individual thelastomatoid species from each host species at each locality in which the thelastomatoid species was found and from which 5 or more specimens were examined. Regional dominance was defined as a combination of overall prevalence, number of localities and number of host species. Overall prevalence was defined as the percentage of specimens infected with a given thelastomatoid species, regardless of host species or locality. XY scatterplots were generated using Excel 2003 (Microsoft). Linear regression analysis of the XY scatterplots was also performed using Excel 2003 (Microsoft).

RESULTS

We examined 845 individual cockroaches from 31 described and 5 undescribed species of Australian burrowing cockroach from 127 localities across Australia (Table 1). For each cockroach species, these localities represented most or all of the known distribution. Five or more cockroach individuals were collected from 65 localities; only data from these host-locality combinations (henceforth referred to as HLCs) were used in subsequent statistical calculations (Tables 2 and 3). The remaining 62 localities were used only to describe parasite distributions.

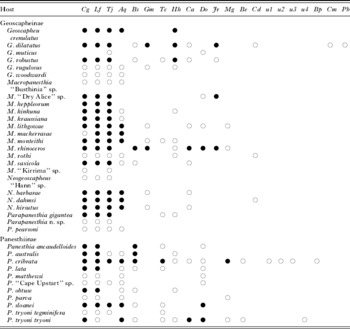

Table 1. Summary of the thelastomatoid guild of each species of Australian burrowing cockroach across all collection sites. Thelastomatoids found from multiple localities (●), thelastomatoids found from only one locality (○)

(Columns represent thelastomatoid species and are sorted by decreasing overall prevalence.)

u1-4=undescribed species 1-4. Aq=Aoruroides queenslandensis; Be=Bilobostoma exerovulvae; Bp=Blattophila praelongacoda; Bs=Blattophila sphaerolaima; Cn=Cephalobellus nolani; Cg=Cordonicola gibsoni; Ca=Coronostoma australiae; Cm=Corpicracens munozae; Do=Desmicola ornata; Gm=Geoscaphenema megaovum; Hh=Hammerschmidtiella hochi; Jr=Jaidenema rhinoceratum; Lf=Leidynemella fusiformis; Mg=Malaspinanema goateri; Pb=Pseudodesmicola botti; Tj=Travassosinema jaidenae; Tc=Tsuganema cribrata.

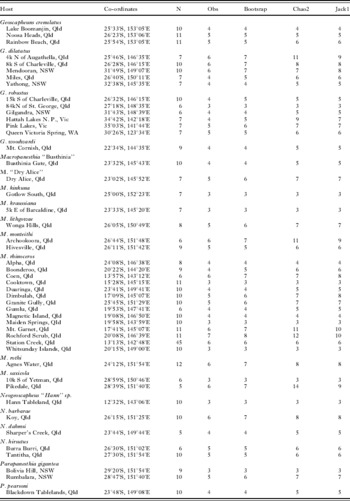

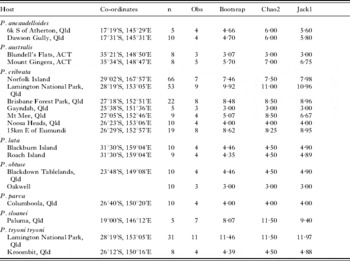

Table 2. Species richness for the thelastomatoid fauna for each geoscapheine species by locality

(Note: Species and localities for which fewer than 4 cockroach specimenswere dissected have not been included.)

Table 3. Species richness for the thelastomatoid fauna for each panesthiine species by locality

(Note: Species and localities for which fewer than 4 cockroach specimens were dissected have not been included.)

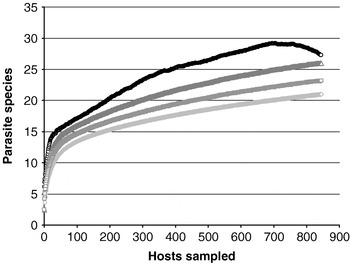

Twenty-one thelastomatoid species were found. Estimated richness for the entire host-parasite system ranged from 23 (Bootstrap) to 27 (Jack1) species (Fig. 1). Observed richness per host-locality combination (HLC) ranged from 3 to 11 species (mean observed richness: 5±2; Bootstrap: 5±2; Chao2: 6±3; Jack1: 6±2). Fifteen thelastomatoid species were recorded from geoscapheines (Bootstrap: 16; Chao2: 16; Jack1: 17) and 16 from panesthiines (Bootstrap: 17; Chao2: 20; Jack1: 19). Ten species were shared by the 2 subfamilies. Six species were found only in geoscapheines. Five species were found only in panesthiines.

Fig. 1. Observed and estimated thelastomatoid species accumulation curves for the entire panesthiine-geoscapheine dataset. Observed richness (◊), Bootstrap estimated richness (□), Chao2 estimated richness (○), Jack1 estimated richness (△).

XY scatterplots were generated comparing mean local prevalence for each thelastomatoid species with its overall prevalence, number of localities and number of host species (Fig. 2). All 3 comparisons resulted in positive correlations (r=0·81, 0·90 and 0·85, respectively) which were statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (d.f.=19; r=0·37).

Fig. 2. Comparison of local dominance versus regional dominance. Mean local prevalence versus overall prevalence (r=0·81) (A). Mean local prevalence versus number of localities (r=0·90) (B). Mean local prevalence versus number of host species infected (r=0·85) (C).

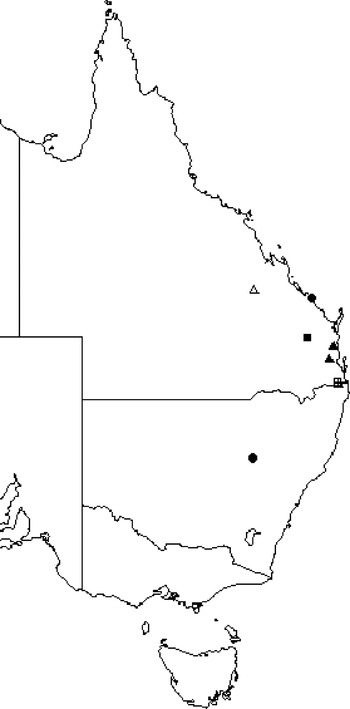

Four thelastomatoid species, Aoruroides queenslandensis, Cordonicola gibsoni, Leidynemella fusiformis and Travassosinema jaidenae, were highly prevalent at local levels (57·1–82·3% of all localities), infected most geoscapheine and panesthiine species and had broad geographical distributions (Fig. 3). Another group, formed by Blattophila sphaerolaima, Coronostoma australiae, Desmicola ornata, Geoscaphenema megaovum, Hammerschmidtiella hochi, Jaidenema rhinoceratum, Malaspinanema goateri and Tsuganema cribrata, were less prevalent (15·8–44·0% of all localities), but still infected numerous host species and had broad distributions (Fig. 4). The remaining 9 species had low to moderate local prevalences (3·0–21·0%) and were recorded from only one or a few contiguous collection sites (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3. Distribution maps for the widespread, dominant thelastomatoid parasites of the panesthiine and geoscapheine species. Aoruroides queenslandensis (A); Cordonicola gibsoni (B); Leidynemella fusiformis (C); Travassosinema jaidenae (D).

Fig. 4. Distribution maps for the mid-range thelastomatoid parasites of the panesthiine and geoscapheine species. Blattophila sphaerolaima (○) and Coronostoma australiae (+) (A); Desmicola ornata (○) and Geoscaphenema megaovum (+) (B); Hammerschmidtiella hochi (○) and Jaidenema rhinoceratum (+) (C); Malaspinanema goateri (○) and Tsuganema cribrata (+) (D).

Fig. 5. Distribution maps for the rare thelastomatoid parasites of the panesthiine and geoscapheine species. Bilobostoma exerovulvae (▲); undescribed species 1–3 (●); undescribed species 4 sp. (+); undescribed species 3 (△); Cephalobellus nolani (■) and Blattophila praelongacoda (□).

DISCUSSION

Survey completeness

For most of the cockroach species examined here, our sampling distribution met or went beyond the known distribution reported by Roth (Reference Roth1977) and Walker et al. (Reference Walker, Rugg and Rose1994). However, a few regions and species have not been adequately sampled. Specifically, Ancaudellia marshallae was not examined. While this species is common in Papua New Guinea and Irian Jaya, it has only been found once in far northern Australia (Roth, Reference Roth1977), and we did not find it. Panesthia cribrata was common in Queensland and Norfolk Island, but was under-represented in parts of New South Wales and all of Victoria. Only small numbers of Geoscapheus muticus, Macropanesthia mackerrasae, M. ‘Kirrima’ sp., Panesthia matthewsi, P. ‘Cape Upstart’ sp., P. tryoni tegminifera and Parapanesthia ‘Mount Molloy’ sp. were examined. Despite these gaps, this dataset is probably as comprehensive as has ever been assembled for the parasites of a significant lineage of terrestrial invertebrates.

Overall parasite species richness estimation

Twenty-one thelastomatoid species were found. Estimated richness for the entire dataset was between 23 and 27 species. The higher value for this range is based on the Chao2 formula. We have found that Chao2 tends to overestimate species richness in the early stage of collection and decreases as sample size increases (unpublished). The species accumulation curve for the entire dataset presented here suggests that this pattern applies to these data. The Chao2-based estimate peaked at 29 species after 696 randomized host dissections and had decreased to 27 having examined 847 specimens. In our experience, once the randomized Chao2 estimate begins to decrease, it does not increase appreciably again. This finding suggests that the true species richness for the host parasite system is probably less than 27 species. This in turn suggests that, although we did not find every thelastomatoid species present in the Geoscapheinae and Panesthiinae, we found all but the rarest species.

Eighteen (28%) of the 65 host-locality combinations, for which species richness was estimated, produced values that were equal to observed richness. Thirty-seven (57%) of the 65, including the above-mentioned 18, produced estimated richness values within 1 of observed richness and 57 (88%) of the 65 estimates were within 2 species of observed richness. These data suggest that, for most host-locality combinations for which more than 5 individuals have been sampled, we found all, or most of the thelastomatoid species present.

Patterns of association

The relationship between mean local prevalence and regional dominance for thelastomatoids was analysed based on 3 parameters: overall prevalence, number of localities, and number of host species. In all 3 comparisons, there was a significant, positive correlation between local prevalence and regional dominance, such that locally rare species tended to have low prevalences throughout the system, were present in few localities and infected few host species. In contrast, locally common species tended to have high prevalences throughout the system, were present in many localities and infected a wide range of host species. No thelastomatoid species was locally dominant and regionally rare.

Dominant species

Four species, Cordonicola gibsoni (present in 85·8% of all HLCs), Leidynemella fusiformis (76·4%), Travassosinema jaidenae (65·4%) and Aoruroides queenslandensis (35·4%), were common in both cockroach subfamilies and had broad distributions. Cordonicola gibsoni and Leidynemella fusiformis were found in every host species, except G. muticus (n=1) in the former, and G. muticus and M. ‘Kirrima’ sp. (n=3) in the latter. Given the low sample sizes for these host species and the high prevalence of these 2 thelastomatoids in the other Australian panesthiines and geoscapheines, we predict that it is likely that C. gibsoni and L. fusiformis also occur in these hosts. Travassosinema jaidenae is common in most panesthiine and geoscapheine species examined, but was not found in P. ancaudelloides (n=16), P. lata (n=19) or P. obtusa (n=20). For the geoscapheine and panesthiine species in which T. jaidenae was found, the mean prevalence was 62·2%. Therefore, it is likely that if T. jaidenae is present in P. ancaudelloides, P. lata or P. obtusa, it is at a greatly reduced prevalence level. Aoruroides queenslandensis, although found in 45 (35·4%) of the 127 localities surveyed, was far more common in the Panesthiinae (9 of 11 species; 81%) than Geoscapheinae (14 of 25 species; 56%). Within the panesthiines, T. jaidenae was only absent from P. ancaudelloides and P. tryoni tegminifera. Given that only 1 specimen of P. tryoni tegminifera was dissected, it cannot be interpreted that A. queenslandensis is absent from this species. Therefore, within the Panesthiinae, only for P. ancaudelloides (n=16) would it be reasonable to suggest that there are enough data to conclude at least a diminished prevalence, if not an absence, of A. queenslandensis. In contrast, of the 11 geoscapheine species for which we have no record of parasitism by A. queenslandensis, all but 3, namely G. muticus (n=1), M. ‘Kirrima’ sp. (n=3) and Parapanesthia ‘Mount Molloy’ sp. (n=1), were sampled at levels that should have been adequate to detect such a relatively prevalent parasite. This finding is especially striking in the apparent absence of A. queenslandensis from one of the most commonly sampled cockroach species in this study, M. rhinoceros (n=129). If this thelastomatoid species is present in many of these geoscapheine species, it must be at a greatly reduced prevalence.

Moderate species

Eight thelastomatoid species occurred at low prevalences (4·7–14·2% of all HLCs) and yet remained widely distributed. Most of these species were far more prevalent in one host subfamily than the other. Three species, B. sphaerolaima, D. ornata and T. cribrata, infected panesthiines prefentially. Seven of the 11 species of panesthiines (64%) were parasitized by B. sphaerolaima and D. ornata, whereas these thelastomatoid species were found in only 4 of the 25 species of geoscapheines (16%). Similarly, T. cribrata was found in 6 panesthiine (55%) and 3 geoscapheine (12%) species. Few specimens of P. matthewsi (3), P. ‘Cape Upstart’ sp. (2) and P. tryoni tegminifera (1) were dissected; further sampling of these species will likely extend the recognized host range of B. sphaerolaima, D. ornata and T. cribrata.

Three thelastomatoids were more common in geoscapheine than panesthiine species. Geoscaphenema megaovum was found at 13·4% of all host-locality combinations examined and was present at a mean prevalence of 26% across all host individuals, regardless of species. Despite being so common, G. megaovum was not found in any panesthiine species. Coronostoma australiae was found in 8 geoscapheine (32%) but only 2 panesthiine species (18%). Jaidenema rhinoceratum was found in 3 geoscapheine species but no panesthiines. Both G. megaovum and J. rhinoceratum have been characterized as ‘aridity specialists’ that have not been found in wet localities (Jex et al. Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2007). Geoscapheines often live in dry areas but panesthiines do not. The restriction of these species to geoscapheines likely reflects host habitat differences rather than physiological specificity.

The remaining 2 thelastomatoids considered in this group are Hammerschmidtiella hochi and Malaspinanema goateri. H. hochi infects numerous geoscapheines and panesthiines and has a broad distribution, whereas M. goateri was found in 3 panesthiine and 2 geoscapheine species. Neither species parasitizes one subfamily more commonly than the other.

Rare species

The remaining 9 thelastomatoid species were rare (prevalences of 0·8–1·6% across all localities), localized, and each was found in just one or a few host species. Within the cockroach species parasitized by these thelastomatoids, the mean prevalence of infection ranged from 3·0 to 21·0%. The female thelastomatoid individuals examined here were fully developed and had uteri containing eggs, inferring genuine parasitism. We suggest 2 possible explanations for the rarity of these species. (1) They may be genuine specialists that are particularly suited to one or a few host species, having a limited geographical distribution. However, one would expect such specialist species to be common, if not dominant, in a specific set of circumstances, although rare or non-existent elsewhere; these species are exceptionally rare or absent everywhere. (2) It is more likely that these are peripheral parasites, or ‘stragglers’, that are more prevalent in another host species in the same area. Jex et al. (Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a) reported significant sharing of thelastomatoid species among some panesthiines and other sympatric, log-dwelling arthropods, such as beetles and millipedes. This included 1 species involved here (undescribed species 4). Although just 1 individual of this species was found in Panesthia tryoni tryoni, it was relatively common in the passalid beetle, Mastachilus quaestionis (21·4% prevalence) (Jex et al. Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a). Thus, ‘straggling’ evidently explains at least some of the rare species examined here. It is important to note that few non-panesthiine and non-geoscapheine arthropods in Australia have been examined for thelastomatoids, and, thus, there is considerable opportunity for further such sharing. We predict that all of the species designated as ‘rare’ will prove to be shared with other arthropods in which they are more common.

A system of low specificity and broad distributions

An analysis of the literature by Jex et al. (Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a) showed that of the ∼350 currently recognized species of Thelastomatoidea, nearly 80% had been recorded from just a single species of cockroach. This figure could be interpreted as suggesting a system of exceptionally high host specificity. However, of those thelastomatoids for which only a single host species is known, 99% (274 of 276) were from a single reporting, thereby revealing very little about the true specificity of these parasites. Despite the number of thelastomatoid species that have been described, for most species virtually nothing is known about the extent of their distributions or the extent to which they are shared between taxonomically or ecologically similar hosts.

We suspect that the appearance, from the published record, of an overall pattern of high host-specificity for thelastomatoid species is spurious and results from more narrowly focused studies and low sample sizes. The present, more completely examined, assemblage reveals a clear pattern of broadly distributed parasites for this group. The majority (71%) of the thelastomatoids reported here parasitize multiple host species and were from multiple localities. We are sceptical that any of the species reported here are genuinely restricted to a single cockroach species. Based on the present findings, it appears evident that a dominant pattern of low host specificity is far more common within the Thelastomatoidea than previously realized.

High or low guild similarity between geoscapheines and panesthiines?

Ten thelastomatoid species (48%) were shared between geoscapheine and panesthiine species. The high degree of sharing presumably reflects the close evolutionary relationship between the 2 subfamilies. A recent molecular phylogeny for representatives of the Geoscapheinae and Panesthiinae (Maekawa et al. Reference Maekawa, Lo, Rose and Matsumoto2003) suggests that the two subfamilies are paraphyletic and will likely be judged as synonymous. Given the close evolutionary relationship between panesthiines and geoscapheines, it is not surprising that such a large number of parasites are shared. In fact, perhaps more interesting, is that 11 (52%) of the thelastomatoid species are not shared between the 2 subfamilies; 6 species (29%) were exclusive to geoscapheines and 5 (23%) to panesthiines. Although most of these species were rare, 2 species (G. megaovum and J. rhinoceratum) are relatively widespread. The ecological differences between these 2 host groups are probably important in explaining these restricted distributions. Panesthiinae burrow in and feed upon decaying wood; they require moist environments and live in large aggregate populations (Roth, Reference Roth1977; O'Neill et al. Reference O'Neill, Rose and Rugg1987; Matsumoto, Reference Matsumoto1988). Geoscapheinae burrow in soil and feed upon leaf litter; they are often found in dry regions and usually live in small familial groups (Roth, Reference Roth1977; Rugg and Rose, Reference Rugg and Rose1991; Matsumoto, Reference Matsumoto1992; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Rugg and Rose1994). Species of the 2 subfamilies never occur precisely sympatrically; and even when parapatric, the habitats are always distinct. For this reason, it is difficult to distinguish between the effects of spatial versus ecological differences between the 2 host groups. However, Jex et al. (Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a) indicated that such differences could be expected to be important. In that study, the sharing of parasites between panesthiines and other log-dwelling and leaf litter-dwelling arthropods was examined. Although there was a high degree of sharing of thelastomatoid species between panesthiines and other log-dwellers, there was no sharing with leaf-dwellers. This information suggests that a common host niche is important in thelastomatoid sharing. The log burrowing versus soil-burrowing ecology of panesthiines and geoscapheines, respectively, is probably a significant contributor to the differences in their respective thelastomatoid faunas. Different local environmental conditions common between the regions in which panesthiines and geoscapheines are found, is another likely contributor to the differences in thelastomatoid fauna. In an examination of the effects of local climate aridity on the thelastomatoid fauna of Macropanesthia rhinoceros, Jex et al. (Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2007) found that thelastomatoid guild richness and composition varied greatly in relation to local climate aridity and that there was a low richness in wet and dry climates and a high richness in moderate climates. Geoscaphenema megaovum and Jaidenema rhinoceratum were widespread throughout arid regions but not found in wet regions. Given the ability for geoscapheines to withstand much more arid conditions than panesthiines, local habitat conditions, particularly local climate aridity, are also likely contributors to thelastomatoid faunal composition of burrowing cockroaches.

The role of coevolution

A number of studies (Brooks and Glen, Reference Brooks and Glen1982; Hugot et al. Reference Hugot, Gardner and Morand1996; Sorci et al. Reference Sorci, Morand and Hugot1997; Hugot, Reference Hugot1998, Reference Hugot1999) have suggested that the pinworm fauna of primates has arisen through coevolution. Because there has been only limited study of other pinworm systems, little is known as to whether this pattern occurs in pinworms of arthropods. Adamson (Reference Adamson1989) reviewed levels of host specificity occurring within the 5 families comprising the Thelastomatoidea. Although he found that the Thelastomatidae appeared to have low specificity, the other 4 host families showed at least moderate levels of specificity. The Pseudonymidae and Hystrignathidae are only known to parasitize water beetles (Coleoptera: Hydrophilidae) and passalid beetles (Coleotpera: Passalidae), respectively. The Protrelloididae are restricted to cockroaches (Blattodea) with the exception of 2 species in orthopterans (crickets), and the Travassosinematidae are restricted to mole crickets (Orthoptera: Gryllotapoidea), except for a few species of Travassosinema found in millipedes (Hunt, Reference Hunt1993, Reference Hunt1996), beetles (Adamson, Reference Adamson1987) or cockroaches (Jex et al. Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2005, Reference Jex, Schneider, Rose and Cribb2006c). Based on the these patterns of specificity, Adamson (Reference Adamson1989) suggested that there was some evidence for co-evolution as an important component of speciation in pinworms of invertebrates and that the apparent lack of specificity within the Thelastomatidae might be misleading because there is evidence that it is paraphyletic relative to the other 4 thelastomatoid families. He suggested that the apparently low specificity of the Thelastomatidae may reflect a spurious taxonomic hypothesis for the family rather than a lack of specificity (Adamson, Reference Adamson1989).

There is no complete phylogenetic analysis for the Panesthiinae and Geoscapheinae. Without a host phylogeny, the analysis of coevolutionary descent is theoretically difficult, but the data presented here suggest that such formal analysis is redundant. Of the 21 species reported from this system, only 2, namely Blattophila sphaerolaima and Blattophila praelongacoda, are congeneric. Ten of the genera reported here, including Blattophila, have been reported from arthropods other than geoscaephines and panesthiines (Adamson and van Waerebeke, Reference Adamson and Noble1992; Jex et al. Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a). Six of the species have been found in hosts other than geocsapheines or panesthiines, and several more show signs of being ‘stragglers’ which are common in other hosts (Jex et al. Reference Jex, Schneider and Cribb2006a). Most of the thelastomatoid species reported in the present study infect multiple host species, with no particular fealty to the currently recognized cockroach generic divisions. There is no evidence that speciation of thelastomatoids has tracked that of the cockroache's hosts in this system. Although the close evolutionary relationship between geoscapheines and panesthiines appears to have resulted in a sharing of thelastomatoid species, a considerable number of species are not shared. The lack of consistency in the taxonomic relationships of these non-shared species suggests that these host-distribution patterns are probably driven by the substantial ecological differences between the 2 host subfamilies and not by high levels of host-specificity or coevolutionary descent.

This study was supported by the Queen Elizabeth II Centennial Scholarship (Government of British Columbia, Canada), The University of Queensland International Postgraduate Research Scholarship, the International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (Government of Australia), and the Australian Biological Research Study. The authors thank Peter Cook, Matt Nolan and Terry Miller for their help in collecting samples.