Introduction

Recognition of parasites as an integral part of global biodiversity (Poulin and Morand, Reference Poulin and Morand2004; Gómez and Nichols, Reference Gómez and Nichols2013) and their roles in structuring natural communities (e.g. Wood et al., Reference Wood, Byers, Cottingham, Altman, Donahue and Blakeslee2007; Mellado and Zamora, Reference Mellado and Zamora2017) and food webs (e.g. Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Dobson and Kuris2006; Sukhdeo, Reference Sukhdeo2012) has led to a burst of studies of parasite community ecology during the last two decades (e.g. Matějusová et al., Reference Matějusová, Morand and Gelnar2000; Gotelli and Rohde, Reference Gotelli and Rohde2002; Poulin and Luque, Reference Poulin and Luque2003; Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Matthee, Lareschi, Korallo-Vinarskaya and Vinarski2010; Dallas et al., Reference Dallas, Laine and Ovaskainen2019). In particular, patterns of variation in species composition ( = compositional turnover) of parasite communities received much attention and were studied in a variety of parasite taxa exploiting various hosts in many geographic regions and in terrestrial, marine and freshwater environments (Perdiguero-Alonso et al., Reference Perdiguero-Alonso, Montero, Raga and Kostadinova2008; Quiroz-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado, Reference Quiroz-Martínez and Salgado-Maldonado2013; Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Shenbrot, Khokhlova, Stanko, Morand and Mouillot2015, Reference Krasnov, Vinarski, Korallo-Vinarskaya and Khokhlova2020; Spickett et al., Reference Spickett, Junker, Krasnov, Haukisalmi and Matthee2017; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Clegg, Sam, Goulding, Koane and Wells2018).

The main aim of many studies of variation in parasite species composition was a search for general laws, i.e. patterns repeatable in several parasites and host taxa. If a general pattern for parasite compositional turnover was found, it would indicate a certain level of predictability of parasite communities. This, in turn, would allow a better understanding of the rules governing these communities and facilitate the prevention of parasitic diseases in humans, livestock and wildlife. It is well known that parasite communities are complex entities that exist in a set of hierarchical scales and are fragmented between host individuals, populations of conspecific hosts (within a locality or between localities), as well as communities of hosts occurring at different localities. Parasite assemblages at these hierarchical scales are termed infracommunities, component communities, and compound communities, respectively (Holmes and Price, Reference Holmes, Price, Kittawa and Anderson1986; Poulin, Reference Poulin2007). Given that parasite communities at the lowest scale (infracommunities) are ephemeral and assembled mainly via demographic processes, whereas communities at the higher scales (component and compound communities) persist much longer and are shaped via evolutionary and biogeographic processes (Morand et al., Reference Morand, Rohde and Hayward2002; Poulin, Reference Poulin2007), it is not surprising that patterns of compositional variation differ between communities of the same parasite taxon at different scales (e.g. van der Mescht et al., Reference van der Mescht, Krasnov, Matthee and Matthee2016; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Kohler and Vonhof2016). In other words, these patterns should be considered separately for each scale.

Recently, Krasnov et al. (Reference Krasnov, Vinarski, Korallo-Vinarskaya and Khokhlova2020) studied compositional turnover in communities of fleas and gamasid mites harboured by small mammals in Western Siberia. They found that the patterns of turnover differed substantially between infracommunities and compound communities. However, the patterns of flea and mite turnover within these hierarchical scales were similar. In contrast, the patterns of turnover in component communities differed between fleas and mites. The study of Krasnov et al. (Reference Krasnov, Vinarski, Korallo-Vinarskaya and Khokhlova2020) dealt with two taxa with (a) similar strategies of parasitism (both haematophagous ectoparasites with alternating periods of staying on the host and being off-host, but remaining in the latter's burrow/nest) and (b) infesting multiple host species. It thus remained unclear whether (a) the patterns found in infracommunities are indeed parasite taxon-invariant and (b) the patterns found in component communities are indeed parasite taxon-dependent but are not affected by the identity of a host species. These questions can be answered by exploring compositional turnover in infracommunities and component communities of parasites with contrasting parasitism strategies (e.g. ectoparasites vs endoparasites) and infecting the same host species. Here, we attempted to fill this gap and studied compositional turnover in infracommunities and component communities of ecto- and endoparasites infesting the same host species, the insectivorous Natal long-fingered bat, Miniopterus natalensis (Chiroptera, Miniopteridae).

Several aspects of its biology make M. natalensis a convenient model for parasite community studies. The species has a wide geographic range in southern Africa, covering several of the South African biomes, and, being a gregarious cave dweller, occurs in large colonies (Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005). The diet of M. natalensis is diverse and largely composed of dipterans, hemipterans, isopterans, lepidopterans and coleopterans, caught entirely on the wing, and with different insect groups being the dominant food items at different sites (Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005; Schoeman and Jacobs, Reference Schoeman and Jacobs2011). Miniopterus natalensis have adapted to a large range of vegetational associations, likely due to their migratory nature, and are limited in their distribution only by the availability of caves or similar extensive shelters as well as an adequate supply of food. Female bats migrate seasonally between wintering roosts where mating and hibernating colonies are formed, and summer maternity roosts where the young are born and raised; while many males undertake this migration as well, they usually only spend a short period of time in the maternity roosts, leaving soon upon the arrival of pregnant females (Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005). There is little morphological variation between males and females (Miller-Butterworth et al., Reference Miller-Butterworth, Jacobs and Harley2003; Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005), but morphological variation between the different subpopulations in South Africa might indicate that these bats have adapted to local environmental conditions, such as vegetation type, climate and/or prey differences (Jacobs, Reference Jacobs1999; Miller-Butterworth et al., Reference Miller-Butterworth, Jacobs and Harley2003). The parasite fauna of bats in Africa is generally poorly known and the majority of studies are of a taxonomic nature (Ortlepp, Reference Ortlepp1932; Jobling, Reference Jobling1936; Zumpt, Reference Zumpt1950; Dubois, Reference Dubois1956; Maa, Reference Maa1965; Baruš, Reference Baruš1973; Saoud and Ramadan, Reference Saoud and Ramadan1976), with few parasite surveys having been conducted (Junker et al., Reference Junker, Bain and Boomker2008). However, studies of bats in other parts of the world demonstrated that they are hosts to a variety of ecto- and endoparasites (Jameson, Reference Jameson1959; Blankespoor and Ulmer, Reference Blankespoor and Ulmer1970; Esteban et al., Reference Esteban, Amengual and Cobo2001; Dick and Gettinger, Reference Dick and Gettinger2005; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Kohler and Vonhof2016).

Following Krasnov et al. (Reference Krasnov, Vinarski, Korallo-Vinarskaya and Khokhlova2020), we investigated patterns of variation in species composition of parasite assemblages harboured by M. natalensis, using a novel metric, zeta diversity (Hui and McGeoch, Reference Hui and McGeoch2014). Zeta diversity (denoted as ζi) measures the average number of species shared by i communities, where i is called the zeta order (Hui and McGeoch, Reference Hui and McGeoch2014). The main advantage of zeta diversity is that, in contrast to traditional pairwise metrics of community dissimilarity (e.g. beta-diversity) that tend to overestimate the contribution of rare species and to underestimate the contribution of common species to compositional turnover (Latombe et al., Reference Latombe, Hui and McGeoch2017), it takes into account the full spectrum of species, independent of the level of their rareness or commonness (McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019). Furthermore, zeta diversity, by definition, represents compositional overlap across multiple (rather than only two) communities and thus expresses compositional change as similarity rather than dissimilarity. Obviously, zeta diversity values inevitably decline with zeta order. The shape of this decline indicates whether either stochastic or niche-based processes drive differentiation of species composition (McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019; see details below).

The aims of this study were threefold. First, we asked whether the patterns of zeta diversity differ between hierarchical scales (i.e. infracommunities vs component communities) and expected predomination of stochastic processes in infracommunities and niche-based processes in component communities. This is because infracommunity dynamics are strongly affected by stochastic demographic processes (Poulin, Reference Poulin2007; see above), whereas the relationships between parasites and local environmental conditions play an important role in the dynamics of component communities (Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Shenbrot, Mouillot, Khokhlova and Poulin2005; Spickett et al., Reference Spickett, Junker, Krasnov, Haukisalmi and Matthee2017; but see Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Vinarski, Korallo-Vinarskaya and Khokhlova2020). Second, we asked whether the patterns of (a) zeta diversity in infracommunities and component communities and (b) variation in zeta diversity over space ( = zeta decay; see details below) in component communities differ between ecto- and endoparasites. We expected a more rapid zeta diversity decline for ecto- than for endoparasites, indicating fewer species shared by many assemblages in the former than in the latter. We also expected higher spatial stability in endo- as compared to ectoparasite communities. This is because the majority (albeit not all) of ectoparasites use their host intermittently, whereas the majority of endoparasites persist in a host individual or population for a much longer period. Third, we asked whether the patterns of zeta diversity and zeta decay differ between subsets of parasite communities harboured by male and female hosts. Earlier, Krasnov et al. (Reference Krasnov, Stanko, Matthee, Laudisoit, Leirs, Khokhlova, Korallo-Vinarskaya, Vinarski and Morand2011) reported that community structure in ectoparasites of rodents was mainly driven by male hosts and that the same factors (e.g. differences in the level of immunocompetence and mobility between male and female rodents) are responsible for both male-biased infection patterns and the male-biased manifestation of parasite community structure. Here, we expected that the patterns of zeta decline and zeta decay would be more pronounced (i.e. steeper zeta decline and zeta decay) in communities harboured by female bats because of female-biased parasitism often reported for ecto- and endoparasites of chiropterans (see Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Bordes, Khokhlova and Morand2012 and references therein).

Materials and methods

Study sites

A total of 96 M. natalensis were captured at seven sites across South Africa during a single summer season (mid-September 2009 to early January 2010), in order to minimize the possible impacts of seasonal migration and/or hibernation. Sampling sites were situated in six of the eight South African Biomes (see Supplementary Material, Appendix 1, Fig. S1, Tables S1 and S2) and included representatives of the three major-subpopulations of this bat species in South Africa: De Hoop Guano Cave in the south; Steenkampskraal Mine, Koegelbeen Sinkhole and Vanderkloof Dam in the west; Sudwala Caves and Shongweni Dam in the northeast, as well as Table Farm in the southeast regions of the country (Miller-Butterworth et al., Reference Miller-Butterworth, Jacobs and Harley2003).

Bat sampling and parasite collection

Bats were caught as they emerged from their roosts at dusk using mist nets and/or harp-traps placed close to the entrance of the roost. Immediately upon capture, bats were temporarily placed into individual cloth bags for later identification of species (following Stoffberg et al., Reference Stoffberg, Jacobs and Miller-Butterworth2004), sex and age (adult or juvenile following Anthony, Reference Anthony and Kunz1988). Any non-target species, pregnant females and juveniles were subsequently released. Pregnancy was determined by palpation and examination of nipples following Racey (Reference Racey1969). Specimens of M. natalensis were placed into sealable glass jars, together with the contents of their holding bags and euthanized using halothane (Leach et al., Reference Leach, Bowell, Allan and Morton2004).

Following euthanasia, the gastrointestinal tracts (GITs) were removed from the bats and placed into individual glass jars. GITs were fixed using boiling water and subsequently transferred into 70% ethanol. Similarly, the dissected bats, as well as ectoparasites, were placed into separate vials containing 70% ethanol. In the laboratory, any endoparasites present were collected from the abdominal cavity of each bat as well as from the various sections of the GIT (stomach, small and large intestine) and stored in 70% ethanol. Identification of endo- and ectoparasites was done following standard procedures and using the relevant taxonomic keys, descriptions and/or re-descriptions. Parasite specimens that could not be identified to species level, but which differed morphologically from each other and all known congeners, were designated as ‘sp. A, B, etc.’ (Supplementary Material, Appendix 2, Tables S2 and S3). Cestodes (Hymenolepididae) and some nematodes (Capillariidae) could only be identified to the family level. The latter two families were each included in the counts for species richness as a single taxon.

Data analyses

The analyses of compositional turnover of ecto- and endoparasites were carried out at two scales. At the scale of infracommunities, we analysed the turnover of parasite species across individual bats within a sampling site. For these analyses, we selected three sampling sites at which 19–20 bat individuals were captured and found infested. These sites were the Sudwala Caves, Koegelbeen Sinkhole and Table Farm (Supplementary Material, Appendix 1, Fig. S1, Table S1). At the scale of component communities, we analysed compositional turnover of parasites across bat populations inhabiting the seven sampling sites (see above).

For each parasite group (i.e. ecto- and endoparasites separately) at each scale (i.e. infracommunities at each of the three sampling sites and component communities), we constructed incidence matrices with bat individuals (for infracommunities) or sampling sites (for component communities) as rows and parasite species as columns. Then, we calculated the zeta decline and retention rate for each of these matrices (Hui and McGeoch, Reference Hui and McGeoch2014; McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019). Zeta decline represents a decrease in the average number of shared species with an increase in the number of sampling units ( = zeta order), that is the number of individual bats for infracommunities and the number of sampling sites for component communities. The steepness of the zeta decline indicates whether compositional turnover is mostly due to rare (steeper decline) or common (shallower decline) species. Given that zeta diversity at ever-increasing orders reflects the relative contribution of species with an ever-increasing degree of commonness (see details in Hui and McGeoch, Reference Hui and McGeoch2014; Latombe et al., Reference Latombe, Hui and McGeoch2017; McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019), the difference between zeta values at successive zeta orders demonstrates the relative difference in the number of rare as compared with that of common species. The shape of zeta decline is most often approximated by either a negative exponential or a power-law function (McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019). Each of these fits indicates the process most likely governing the differentiation of species composition. An exponential or a power-law fit suggests either equal or unequal chances, respectively, for species to occur in a given host individual or at a locality and, thus, indicates whether stochastic or niche-based processes, respectively, are the main mechanism of species turnover (Hui and McGeoch, Reference Hui and McGeoch2014; McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019).

The zeta ratio is a quotient of two consecutive zeta values with a preceding zeta order as a denominator and a subsequent zeta order as a numerator. This ratio measures the proportion of species that remain ( = retained) if more host individuals or sampling sites are added for calculating zeta values (Hui and McGeoch, Reference Hui and McGeoch2014). A plot of zeta ratios against the denominator zeta orders is called a retention rate curve. The shape of a retention rate curve (increasing, asymptotic, modal, decreasing) indicates the rate and pattern at which common species remain across host individuals or sampling sites from low to high zeta orders (see McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019). For example, a modal curve indicates a complete turnover in the species composition beyond a certain zeta order. An asymptotic curve suggests the presence of certain species in all hosts or at all sampling sites. An ascending curve shows that common but not rare species are retained in additional samples and that the community is likely under-sampled.

To quantify variation in the number of shared species with an increase in distance between sampling sites, Hui and McGeoch (Reference Hui and McGeoch2014) adapted the concept of the distance decay of similarity (Nekola and White, Reference Nekola and White1999) to zeta diversity. This adaptation is called zeta decay and is represented by a series of plots of zeta values for samples distributed at different distances across zeta orders, visualizing thus the variation in the number of species shared by communities in dependence of spatial distance between them. The differences between slopes of zeta decay of different zeta orders allow the differentiation of spatial trends between rare and common species (low zeta orders and high zeta orders, respectively). Obviously, zeta decay was analysed for component communities only.

All calculations were carried out using the package ‘zetadiv’ (Latombe et al., Reference Latombe, McGeoch, Nipperess and Hui2018a) implemented in R (R Core Team, 2019). Initially, we analysed patterns of zeta diversity (zeta decline, retention rate, zeta decay), pooling data on parasites harboured by both male and female bats. To understand whether these patterns are affected by host sex, we then repeated all analyses for parasites infecting only male or only female hosts. Calculations of the values of zeta diversity and zeta ratio were done for all orders of zeta available for a given matrix, whereas zeta decay was calculated for orders 2–5 or 2–4 (because no female bats were captured at the Steenkampskraal Mine).

Results

Parasite assemblages

Miniopterus natalensis harboured diverse parasite assemblages, comprising ectoparasites, including flies, mites, ticks and fleas as well as endoparasites, represented by nematodes, cestodes and trematodes (Supplementary Material, Appendix 2, Table S1). Of the 15 species of ectoparasites, mites were the most speciose (n = 9), whereas ticks and fleas were represented by a single species each, namely Ixodes simplex (Ixodidae) and Oxyparius isomalus (Ischnopsyllidae), respectively. Only three bat individuals were not infested by any ectoparasites at all and prevalence (proportion of infested individuals) of the various ectoparasite species ranged from 0.01 to 0.75. The highest prevalence was seen in the nycteribiid bat fly Nycteribia schmidlii (0.75), followed by two species of mites, Spinturnix semilunaris (0.406) and Macronyssus sp. C (0.344). Mean abundance (mean number of parasites per individual bat) was generally low, ranging from 0.01 ± 0.01 (recorded in four species) to 2.09 ± 0.23 in N. schmidlii.

Among the 11 endoparasite taxa, the onchocercid nematode Litomosa chiropterorum had by far the highest prevalence (0.667) as well as the second-highest mean abundance (7.32 ± 1.16); the latter only exceeded by that of the lecithodendriid trematode Paralecithodendrium khalili (14.95 ± 8.11), which also had the highest prevalence (0.146) among the trematodes. Hymenolepidid cestodes had a prevalence of 0.156, with a mean abundance of 0.24 ± 0.07. Mean abundance of the remaining taxa ranged from 0.01 ± 0.01 to 1.57 ± 1.01. Similar to the ectoparasites, only five hosts remained uninfected. Mean ectoparasite and endoparasite species richness on/in an individual bat across all sampling sites were 2.87 ± 0.14 and 1.89 ± 0.10, respectively, with no significant differences between male and female bats (ANOVAs; F 1,91 = 0.67 for ectoparasites and F 1,94 = 0.08 for endoparasites, respectively, P > 0.40 for both) (see Supplementary Material, Appendix 1, Table S1 for parasite species richness per site).

Compositional turnover in infracommunities

The average number of shared ecto- and endoparasite species declined as the number of bat individuals included in the calculations increased and attained zero at zeta orders smaller than or equal to the total number of bats (Table 1, Fig. 1). The rate of this decline for ectoparasites was either steeper (at Table Farm) or equal (at Koegelbeen Sinkhole) or else shallower (at Sudwala Caves) than that for endoparasites (Fig. 1). The shape of the zeta decline was consistently best fitted by the negative exponential function (Table 1). Retention curves for infracommunities of both ecto- and endoparasites were modal, attaining zero at higher zeta orders (Fig. 1). Initially, all curves increased, and then, the zeta ratios dropped beyond zeta orders 4–5 for ectoparasites and 4–6 for endoparasites (Table 1). The difference in the probabilities of retaining common species between ecto- and endoparasite infracommunities varied between sampling sites with the probability of retaining common ectoparasites being higher than that of endoparasites at Sudwala Caves and Koegelbeen Sinkhole, whereas the opposite was the case for Table Farm (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate curves for ecto- and endoparasite infracommunities harboured by Miniopterus natalensis at the Sudwala Caves (a, b), Koegelbeen Sinkhole (c, d) and Table Farm (e, f). The legend on the plot (a) also applies to other plots.

Fig. 2. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate curves for ecto- (Ect) and endoparasite (End) infracommunities harboured by male and female Miniopterus natalensis at the Sudwala Caves. The legend on the zeta decline plot for ectoparasites also applies to other plots.

Table 1. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate for ecto- and endoparasite infracommunities harboured by Miniopterus natalensis at three sampling sites

Site (N): SC, Sudwala Caves; KGBS, Koegelbeen Sinkhole; TF, Table Farm; Parasites (N): Ect, ectoparasites; End, Endoparasites; N, number of species. Sex (N): Both, both male and female hosts; M, male hosts; F, female hosts; N, number of individuals. ζ = 0: zeta order at which zeta diversity attains zero, ΔAIC: difference in Akaike Information Criterion between the negative exponential and the power-law regression of zeta diversity values against zeta order, E/P: whether the negative exponential (E) or the power-law (P) fit was found to be the best; Shape, shape of zeta retention curve; OrderMax: zeta order at which zeta ratio attains maximal value.

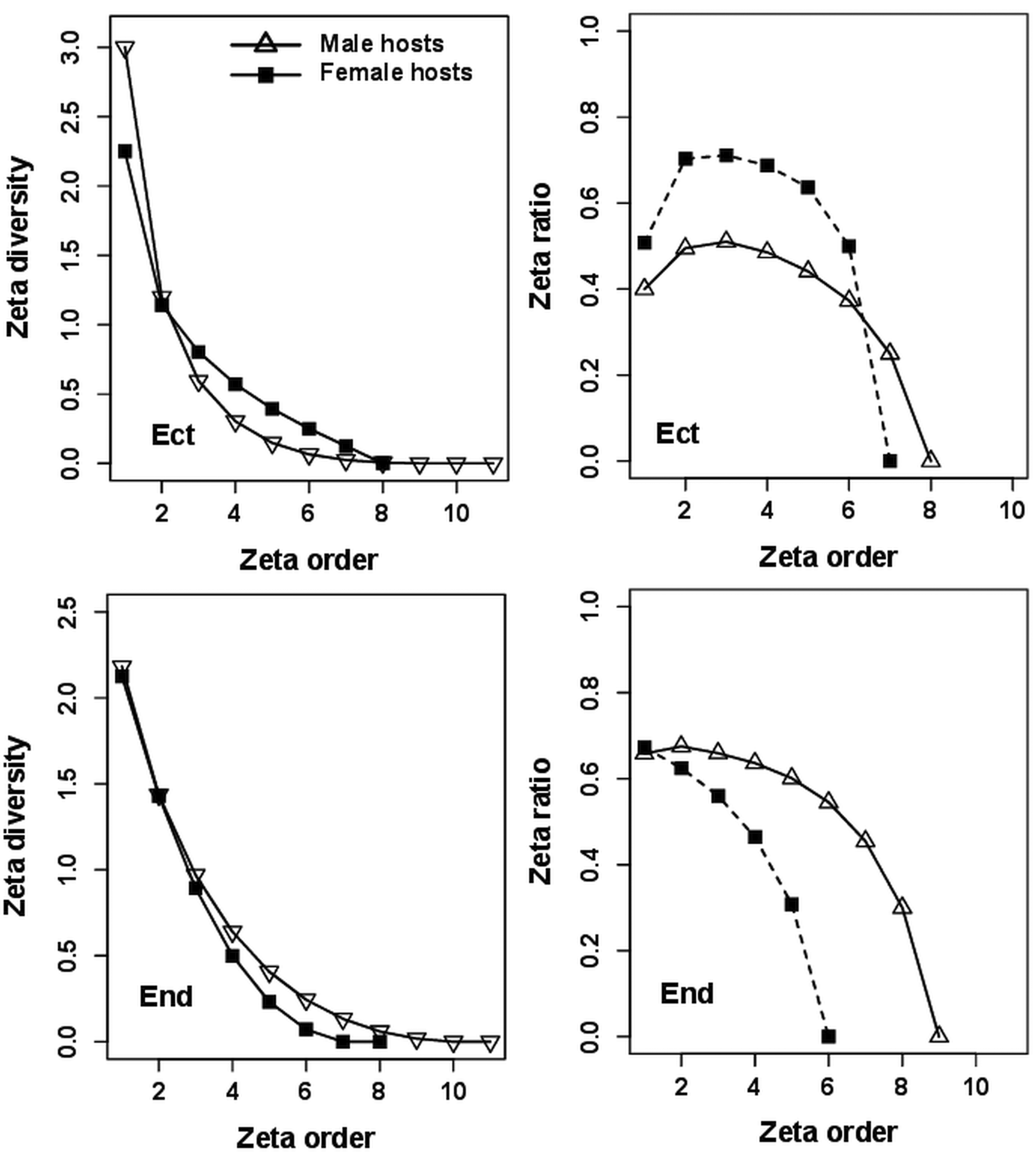

The shape of a decrease in the number of ecto- or endoparasite species with an increase in the number of bats was similar in infracommunities harboured by male or female bats (Figs 2–4, Table 1); except the zeta decline of ectoparasites was shallower in male than in female hosts at Sudwala Caves. However, the probability of retaining common ecto- or endoparasites differed between male- and female-harboured infracommunities with the pattern of this difference varying both between parasite groups and between sampling sites (Figs 2–4). Nevertheless, the shape of zeta decline for both ecto- and endoparasites harboured by both male and female hosts and in the three sampling sites was consistently best fitted by the negative exponential function (Table 1).

Fig. 3. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate curves for ecto- (Ect) and endoparasite (End) infracommunities harboured by male and female Miniopterus natalensis at the Koegelbeen Sinkhole. The legend on the zeta decline plot for ectoparasites also applies to other plots.

Fig. 4. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate curves for ecto- (Ect) and endoparasite (End) infracommunities harboured by male and female Miniopterus natalensis at the Table Farm. The legend on the zeta decline plot for ectoparasites also applies to other plots.

Compositional turnover in component communities

Values of zeta diversity of component communities of ecto- and endoparasites harboured by both males and females declined with an increase in the number of sampling sites and did not attain zero at high zeta orders with two ectoparasites (the nycteribiid N. schmidlii and the spinturnicid S. semilunaris) and one endoparasite (the onchocercid L. chiropterorum) infecting bats at every sampling site (Fig. 5). The best fit of zeta decline for ectoparasites was found to be negative exponential (although the difference between power and exponential fit was small), whereas zeta decline for endoparasites was best described by the power-law function (Table 2). The rate of the zeta decline in component communities of ectoparasites was slightly slower than that for endoparasites (Fig. 5). The retention rate curve for ectoparasite component communities tended to be modal with a slow increase to zeta order 5 and then a slow decrease to zeta order 6 (Fig. 5). In endoparasites, the retention rate curve was ascending, attaining the highest zeta ratio of 0.875 (Table 2, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate curves for ecto- and endoparasite component communities harboured by Miniopterus natalensis. The legend on the zeta decline plot also applies to the retention rate plot.

Table 2. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate for ecto- and endoparasite component communities harboured by Miniopterus natalensis across sampling sites

Parasites (S, N): Ect, ectoparasites; End, Endoparasites; S, number of sites; N, number of species. Sex: Both, both male and female hosts; M, male hosts; F, female hosts. ζ = 0: zeta order at which zeta diversity attains zero, ΔAIC: difference in Akaike Information Criterion between the negative exponential and the power-law regression of zeta diversity values against zeta order, E/P: whether the negative exponential (E) or the power-law (P) fit was found to be the best; Shape: shape of zeta retention curve; OrderMax: zeta order at which zeta ratio attains maximal value.

Patterns of compositional turnover in component communities of ectoparasites harboured by either male or female hosts did not substantially differ from patterns found when data on ectoparasites were pooled for both host sexes, except that the modal shape of the retention rate curves was distinctly more pronounced (Fig. 6). The shape of zeta decline was fitted by the negative exponential function with the absolute value of the coefficient of the fit being about 30% higher for male- than female-harboured communities (Table 2), indicating a faster decrease in the average number of shared species with an increasing number of sites for the latter as compared with the former. Similar to turnover in component communities of endoparasites pooled for all host individuals within a site, zeta decline of both male- and female-harboured endoparasites was best described by the power-law function (Table 2, Fig. 6) and the retention rate curves were ascending.

Fig. 6. Zeta diversity decline and retention rate curves for ecto- (Ect) and endoparasite (End) component communities harboured by male and female Miniopterus natalensis. The legend on the zeta decline plot for ectoparasites also applies to other plots.

The rates of distance decay in the number of shared species were low and pronounced mainly for rare species (i.e. low zeta orders) for ectoparasites and moderately common species for endoparasites (zeta orders 3–4) (Table 3, Fig. 7). There was more ubiquitous ectoparasite than endoparasite species. For example, over distances of 100 km, there were, on average, 4–7 shared ectoparasites and 1–3 endoparasites (across zeta orders). Nevertheless, the number of shared endoparasites declined more slowly with distance than the number of shared ectoparasites did. In addition, there was no distance-associated trend in endoparasite zeta diversity beyond zeta order 4 (Table 3, Fig. 7). When the zeta decay was calculated for parasites infecting male and female bats separately, the rate of the decay for ectoparasites appeared to be slightly higher for male than female hosts (Table 3, Fig. 7). In endoparasites, the number of species shared by male bats across 2–4 sampling sites demonstrated a weak decay with the distance between these sites, whereas no zeta decay with distance was found in species shared by female bats for any zeta order (Table 3, Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Distance decay of zeta diversity for ecto- and endoparasite component communities harboured by Miniopterus natalensis for zeta orders 2–5 (separately for both sexes, male hosts only and female hosts only).

Table 3. Zeta diversity decay across space for ecto- and endoparasite component communities harboured by Miniopterus natalensis across sampling sites

Parasites: Ect, ectoparasites; End, endoparasites. Sex: Both, both male and female hosts; M, male hosts; F, female hosts.

Discussion

Our expectations were partly supported. We found that the pattern of compositional turnover differed between infracommunities and component communities in endoparasites, but not ectoparasites. As we expected, (a) the shape of zeta decline for infracommunities indicated that there were approximately equal probabilities of ecto- and endoparasitic species to occur in any bat individual within a sampling site and (b) distribution of endoparasite species across component communities was likely driven by niche-based processes. Contrary to our expectations, the shape of zeta decline for component communities of ectoparasites suggested the lack of structure in these communities and stochasticity of ectoparasite turnover. Our prediction regarding the rate of zeta decline in ecto- and endoparasites has not been supported. In general, the direction of difference in the rate of zeta decline between ecto- and endoparasites in infracommunities varied across sampling sites, whereas zeta diversity for ectoparasites declined more rapidly than that for endoparasites in component communities. Turnover in the component community composition of ectoparasites appeared to be more spatially dependent than that of endoparasites. Furthermore, the spatial independence of compositional turnover in endoparasites was mainly due to subcommunities harboured by female bats. In other words, patterns of zeta decay in female as compared to male bats contradicted our prediction, whereas our prediction regarding host sex-specific patterns of zeta decline of parasites was supported. In particular, the average number of shared parasite species declined faster in female bats, although this was true for component communities only. In infracommunities, the rates of zeta decline of parasites did not differ substantially between male and female hosts.

Ectoparasites and endoparasites

Compositional turnover of both ecto- and endoparasites among individual bats was characterized by a decline of zeta diversity to zero at zeta orders smaller than the total number of infected bats (except for endoparasites at Table Farm; Table 1). This means that (a) no parasite species infected all bats at a given locality and (b) the entire parasite community was well represented by parasitological examination at each site. The modal shape of the retention rate curves supported these conclusions. Indeed, zeta ratios attained their highest values at low and median zeta orders (from the lowest zeta order 2 in endoparasites at Koegelbeen Sinkhole to the highest zeta order 6 for endoparasites at Table Farm) and dropped to zero at high zeta orders. The modal shape of the retention rate curve indicating fast loss of rare species (the fastest for endoparasites at Koegelbeen Sinkhole), and either medium (ecto- and endoparasites at Koegelbeen Sinkhole) or slow (ectoparasites at Sudwala Caves and endoparasites at Table Farm) loss of widespread species (McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019). The form of zeta decline for both ecto- and endoparasites in infracommunities consistently indicated a lack of structure. The main reason for this is the ephemerality of an infracommunity with its lifespan limited by the lifespan of an individual host (Poulin, Reference Poulin2007), although the longevity of bats is much greater than that of non-flying mammals of similar size (e.g. Wilkinson and South, Reference Wilkinson and South2002). This is especially true for ectoparasites because many of them infest the host only for the time needed to engorge and then fall off (Lehane, Reference Lehane2005). For example, the ectoparasite assemblages of M. natalensis are dominated by macronyssid mites and nycteribiid bat flies. Adults of the former come into contact with their hosts only when a bloodmeal is due, are fast feeders, engorge within minutes and subsequently leave the host (Radovsky, Reference Radovsky and Houck1994; Dowling, Reference Dowling, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006), whereas the latter readily disperse among bat individuals (Dick and Patterson, Reference Dick, Patterson, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006).

The lack of structure in endoparasite assemblages may be associated with species that can be easily exchanged between individual bats inhabiting the same roost, such as directly transmitted nematodes or the vector-transmitted filarial nematode L. chiropterorum. Little is known about the life cycle of any of the monoxenous nematodes of bats. According to Moravec et al. (Reference Moravec, Prokopič and Shlikas1987), some species of Aonchotheca are monoxenous whereas others are heteroxenous, with oligochaetes as typical intermediate hosts. Given the prey spectrum of M. natalensis and that prey is caught on the wing (Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005; Schoeman and Jacobs, Reference Schoeman and Jacobs2011), we consider it more likely that specimens of Aonchotheca collected in the present study, are monoxenous. It follows that the majority of nematodes collected from the bats in the present study, except for Physaloptera sp. and L. chiropterorum, have a direct life cycle. Junker et al. (Reference Junker, Bain and Boomker2008) attributed the high prevalence of the molineid Molinostrongylus ornatus in M. natalensis to host density-induced accumulation of infective stages in the environment at De Hoop Guano Cave. Miniopterus natalensis form tightly packed clusters in their roosts (Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005), and it is likely that this proximity facilitates parasite transmission. To date, the life cycle of L. chiropterorum or any of its congeners is unknown, but filariae, in general, are transmitted by haematophagous arthropods. The genus Litomosa is closely related to another onchocercid genus parasitic in bats, Litomosoides (Junker et al., Reference Junker, Barbuto, Casiraghi, Martin, Uni, Boomker and Bain2009), which is transmitted by haematophagous macronyssids (Guerrero et al., Reference Guerrero, Bain, Attout and Martin2006). It thus seems likely that L. chiropterorum is freely transmitted between individuals of M. natalensis by their macronyssid parasites during blood feeding, contributing to the observed lack of structure in the endoparasite assemblages of M. natalensis.

In contrast to infracommunities, the patterns of species turnover in component communities differed between ecto- and endoparasites. The shape of the zeta decline for ectoparasites was exponential. However, there was little difference between power and exponential fit (ΔAIC = 0.75). This suggests that both stochastic and deterministic (niche-driven) processes play a role in ectoparasite species assembly. In other words, turnover of some ectoparasite species among sampling sites was stochastic, whereas the distribution of other ectoparasite species among these sites was affected by their environmental preferences. For example, streblid bat flies of the genus Ascodipteron spend their entire life on a bat, with females embedded in the skin of their hosts (Maa, Reference Maa1965), whereas spinturnicid mites do not leave the wing membrane of their host (Dick and Patterson, Reference Dick, Patterson, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006). The strong dependence of these species on an individual bat host is presumably accompanied by their low dependence on external environmental conditions so that their distribution across sampling sites is stochastic. On the other hand, I. simplex is a tick with a three-host life cycle: each active stage attaches to a host for a period of several days, engorges and falls off; moulting takes place in the roost substrate and each emerging stage has to find a new host to further continue its development (Durden, Reference Durden, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006; Sándor et al., Reference Sándor, Corduneanu, Péter, Mihalca, Barti, Csősz, Szőke and Hornok2019). Obviously, once detached from their bat hosts, these ticks are strongly influenced by external conditions. Given the strong environmental preferences (i.e. distinct environmental niche) reported for many ixodid species, I. simplex may be responsible for the niche-associated component in the parametric form of the zeta decline for ectoparasites.

The shape of the zeta decline across component communities of endoparasites clearly demonstrated unequal probabilities among helminth species to occur across compound communities. In other words, the most likely assembly processes of component communities of endoparasites are niche-based. The two main components of a niche for any parasite species are the component associated with its hosts (see Poulin et al., Reference Poulin, Krasnov and Mouillot2011 for review) and another associated with the external environment. Evidently, the host-associated niche component does not play any role when parasite communities harboured by the same host species are considered, as in the present study. Consequently, the pattern of compositional change of endoparasite communities was most likely determined by (a) differences in the degree of environmental tolerance/environmental preferences of immature stages among both monoxenous and heteroxenous taxa and (b) differences in the availability of intermediate hosts among sampling localities for heteroxenous endoparasites. For example, variation in air temperature and vegetation structure among sites may affect the occurrence of nematodes with direct life cycles because they require suitable environments for egg survival and larval development (e.g. Hulbert and Boag, Reference Hulbert and Boag2001). The abundance of various terrestrial arthropods that serve as intermediate hosts for many hymenolepidid cestodes (Georgiev et al., Reference Georgiev, Bray, Timothy, Littlewood, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006) and nematodes such as Physaloptera species (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000) as well as terrestrial molluscs and aquatic insects that serve as intermediate hosts for trematodes such as Paralecithodendrium species (Kudlai et al., Reference Kudlai, Stunžėnas and Tkach2015), is most certainly affected by environmental conditions and will thus vary among localities. This, in turn, leads to variation in the species composition of endoparasite communities harboured by the same host species at these localities (e.g. Dybing et al., Reference Dybing, Fleming and Adams2013; Spickett et al., Reference Spickett, Junker, Krasnov, Haukisalmi and Matthee2017).

Spatial decay of zeta diversity for both ecto- and endoparasites, respectively, was pronounced at lower zeta orders only, indicating that changes in species composition over space were due to rare species (e.g. Latombe et al., Reference Latombe, Richardson, Pyšek, Kučera and Hui2018b). Furthermore, the number of shared ectoparasite species decreased with the distance between localities faster than the number of shared endoparasites for the same zeta order. This suggests that endoparasite turnover was much less dependent on the distance between sites than that of ectoparasites. At first glance, this contradicts our results on mainly random (i.e. stochastic) ectoparasite vs structured (i.e. deterministic) endoparasite communities. However, it is still unclear whether the distance decay in community similarity arises from random and dispersal-related (i.e. neutral; Hubbell, Reference Hubbell2001) or niche-related processes (Cottenie, Reference Cottenie2005), with numerous empirical studies supporting either the former or the latter hypothesis (e.g. Carola and Baselga, Reference Carola and Baselga2018 vs Bahram et al., Reference Bahram, Koljalg, Courty, Diedhiou, Kjøller, Polme, Ryberg, Veldre and Tedersoo2013, respectively). In other words, stochastic vs niche-based assembly processes may not necessarily be associated with the relationship between the average number of shared species and the average distance between communities. In indirect support of this, distance explained only a small part of the variation in bat gene flow between these sites, suggesting that other factors, besides distance, determine bat movement between sites (Miller-Butterworth et al., Reference Miller-Butterworth, Jacobs and Harley2003).

Male hosts and female hosts

In contrast to the majority of small mammals, parasitism in chiropterans is mainly female- rather than male-biased (see Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Bordes, Khokhlova and Morand2012 for review). The reason behind this difference is that, for example, rodent males are characterized by higher mobility and lower immunocompetence (due to the immunosuppressive effect of testosterone) and thus have a higher chance to encounter parasites, combined with a reduced ability to cope with parasitism (see Krasnov et al., Reference Krasnov, Bordes, Khokhlova and Morand2012 and references therein). In bats, female-biased parasitism has also been attributed to reduced resistance to parasites (in terms of, for example, immunocompetence) in reproducing females at early stages of pregnancy (McLean and Speakman, Reference McLean and Speakman1997; Christe et al., Reference Christe, Arlettaz and Vogel2000) or increased survival of parasites due to presumably better nutrition status in non-reproductive females (Christe et al., Reference Christe, Giorgi, Vogel and Arlettaz2003, Reference Christe, Glaizot, Evanno, Bruyndonckx, Devevey, Yannic, Patthey, Maeder, Vogel and Arlettaz2007). However, in this study, we examined parasite assemblages in adult male and adult non-reproductive female bats only; consequently, behavioural (in terms of mobility) and hormonal differences between the sexes were likely minor, which resulted in similar parasite species richness in male and female M. natalensis. Nevertheless, the shape of zeta decline was steeper for parasites harboured by the female as compared to male bats. Furthermore, the retention rate curves suggested that common ectoparasites are more likely retained across sites in male-harboured subcommunities than in female-harboured subcommunities. This may be the result of differential survival of ectoparasites on males and females but in an opposite manner to that found by Christe et al. (Reference Christe, Glaizot, Evanno, Bruyndonckx, Devevey, Yannic, Patthey, Maeder, Vogel and Arlettaz2007).

Another explanation for the observed difference in retention rates of ectoparasites between male and female bats might be associated with the increased mobility of male M. natalensis within their natal area (van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe1975), exposing them to ectoparasites from other caves. Like female M. natalensis, male M. natalensis bats return to their natal caves (van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe1973; Miller-Butterworth et al., Reference Miller-Butterworth, Jacobs and Harley2003) and occupy the same maternity caves with females and pups, after mating has occurred in hibernacula (van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe1973). However, males then leave the maternity caves for other as yet unknown caves (van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe1975), where they may be exposed to other ectoparasites either from the caves or other species of bats with whom they share these caves.

In addition, the ascending retention rate curve of endoparasites in subcommunities of female bats hinted that the sampling extent was, perhaps, smaller than the entire female-associated helminth metacommunity (McGeoch et al., Reference McGeoch, Latombe, Andrew, Nakagawa, Nipperess, Roigé, Marzinelli, Campbell, Vergés, Thomas, Steinberg, Selwood, Henriksen and Hui2019). Indeed, no female bats were captured at the Steenkampskraal Mine, while the only three females captured at De Hoop Guano Cave were not infected with any helminths.

Patterns of zeta decay for ectoparasites did not reveal any substantial differences between subcommunities on male and female bats in the association between ectoparasite zeta diversity and distance. However, the compositional similarity in endoparasite subcommunities harboured by female bats did not differ between sampling sites situated at either short or long distances. In other words, the dependence of endoparasite turnover among localities on the distance between these localities was due to parasites residing in male but not female hosts. Here, too, these differences might be associated with differences in mobility between males and females. Although nuclear and mitochondrial DNA supports strong philopatry in both sexes of M. natalensis, additional movement of males within their natal area compared to females is reflected in a weak but significant correlation between genetic variation and distance for females suggesting that females may move less than males (Miller-Butterworth et al., Reference Miller-Butterworth, Jacobs and Harley2003; see also van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe1973, Reference van der Merwe1975). This additional movement by males may also be accompanied by additional parasite exchange between males. Mark-recapture studies support the notion that movement of both males and females within the natal area is more complex and involves the use of more caves, at least by males, than just those associated with hibernation or the rearing of pups. Females, and some males, form pre-maternity colonies in different caves used for maternity colonies but tended to use the same set of caves each year. Males from different maternity colonies may disperse from these colonies, leaving females and pups behind, and move to, as yet, unknown caves. Some males return to the hibernacula and the maternity caves before the females and will leave the maternity caves as more females arrive from the pre-maternity caves for other unknown caves (van der Merwe, Reference van der Merwe1973, Reference van der Merwe1975). One of the consequences of these complex movement patterns to caves not used by females but shared with other males may be higher chances for parasite exchange between males from different localities, as well as exposure to a wider variety of possible intermediate hosts.

In conclusion, our results support the results of Krasnov et al. (Reference Krasnov, Vinarski, Korallo-Vinarskaya and Khokhlova2020) that the rules governing compositional turnover in parasite communities for the lowest hierarchical scale (infracommunities) are taxon-invariant. The patterns of compositional turnover in infracommunities were similar in ecto- and endoparasites, whereas the patterns of turnover in component communities differed between these parasite groups.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182020001602.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jonathan Aronson, Hassan Babiker, Lizelle Odendaal and Alicia Thomas for their assistance in the field. Thanks also to Cape Nature and the South African National Biodiversity Institute for allowing us access, accommodation and logistical support whilst in the field. Specific thanks go to the staff of the De Hoop Nature Reserve, Shongweni and Vanderkloof Dams, the owners/stewards of Koegelbeen Farm (Johan Cornelissen), Table Farm (Francie White), Steenkampskraal Mine (Sarel Mostert) and Sudwala Caves (Philip du Toit) for their help and guidance on site. This is publication no. 1083 of the Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology.

Financial support

Funding for this research was provided by the KW Johnstone Research Scholarship and the Postgraduate Entrance Level Scholarship, via the UCT Postgraduate Funding Office as well as from a Grant to David S. Jacobs from the South African Research Chair Initiative (funded by the Department of Science and Technology and administered by the National Research Foundation, South Africa GUN 64798).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Ethical clearance for this research was obtained from the Science Faculty Animal Ethics Committee, University of Cape Town (ethics clearance number 2009\V16\SW). Permits to capture and handle bats were obtained from the relevant provincial authorities of the KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, Northern Cape, Eastern Cape and Western Cape Provinces, South Africa.