Article contents

Clotrimazole, ketoconazole, and clodinafop-propargyl inhibit the in vitro growth of Babesia bigemina and Babesia bovis (Phylum Apicomplexa)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 October 2003

Abstract

We evaluated the growth inhibitory efficacy of the imidazole derivatives, clotrimazole (CLT) and ketoconazole (KC), and the herbicide clodinafop-propargyl (CP), in in vitro cultures of Babesia bovis and B. bigemina. Clotrimazole was effective in a dose range of 15 to 60 μM (IC50: 11 and 23·5 μM), followed by KC (50 to 100 μM; IC50: 50 and 32 μM) and CP (500 μM; IC50: 265 and 390 μM). In transmission electron microscopy, extensive damage was observed in the cytoplasm of drug-treated parasites. Combinations of CLT/KC, CLT/CP and CLT/KC/CP acted synergistically in both parasites. In contrast, the combination of KC/CP was exclusively effective in B. bovis, but not in B. bigemina.

Keywords

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- 2003 Cambridge University Press

INTRODUCTION

Bovine babesiosis is a well-recognized tick-borne protozoan disease of cattle in most tropical, subtropical, and some temperate regions of the world (Kuttler, 1988). Babesia bovis and B. bigemina are two of the major aetiological agents that cause severe babesioses in ruminants, characterized by haemolytic anaemia, fever, haemoglobinuria, and even death in acute cases (Ristic, 1988). Therefore, babesiosis is a major threat to the livestock industry (Kuttler, 1988).

Currently, several babesiacidal drugs e.g. imidocarb (Carbesia®), oxytetracycline and diminazene (Berenil®) (Kuttler & Johnson, 1986; de Vos et al. 1994) and, moreover, live vaccines (de Vos & Bock, 2000), acaricides and tick-vaccines (Jonsson et al. 2000) are available. Nevertheless, in B. bovis, the occurrence of drug resistance against imidocarb (Dalgliesh & Stewart, 1977) and amicarbalide isethionate (Yeruham, Pipano & Davidson, 1985) has been reported. Therefore, the development of a new and effective chemotherapy of bovine babesiosis should be a continuing endeavor.

The 2 imidazole derivatives and anti-fungal agents clotrimazole (CLT) and ketoconazole (KC), were potent inhibitors of the in vitro growth of Plasmodium falciparum (Pfaller & Krogstad, 1983; Tiffert et al. 2000). KC was additionally effective against P. berghei and Trypanosoma cruzi in vivo (Raether & Seidenath, 1984). The herbicide clodinafop-propargyl (CP) inhibited the in vitro growth of Toxoplasma gondii (Zuther et al. 1999). Recently, we demonstrated the potent growth inhibitory efficacy of these compounds against the equine B. equi and B. caballi in an in vitro culture system (Bork et al. 2003 b). Therefore, the inhibitory effects of CLT, KC and CP against the bovine Babesia parasites, as well as possible synergistic and antagonistic effects in combined applications, were examined in the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and in vitro cultivation

The Texas strain of B. bovis (Hines et al. 1992) and the Argentina strain of B. bigemina (Hotzel et al. 1997) were grown in a 10% bovine red blood cell suspension according to the method for the continuous microaerophilous stationary-phase culture system (Igarashi et al. 1998).

Chemicals

CTL (1-[α-(2-chlorophenyl)benzhydryl]imidazole) and KC (cis-1-acetyl-4-[4-[[2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-2-(1H-imidazole-1-ylmethyl)-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl]methoxy]phenyl]piperazine) were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO, USA), and CP (2-propynyl(R)-2-[4-(5-chloro-3-fluoro-2-pyridyloxy)phenoxy]propionate), from Riedel-de Haën Laborchemikalien (Seelze, Germany). Stock solutions of 25 mM were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (WAKO Pure Chemical Industrial Ltd, Osaka, Japan) as a solvent and stored at −30 °C until use. It was established that DMSO was not toxic to parasites or host cells (Tables 1 and 2).

In vitro growth inhibition assay of each drug and drug combination test

The in vitro growth inhibition assays followed the method previously described by Igarashi et al. (1998) and Bork et al. (2003 a). Different drug concentrations were prepared by dissolving the active compounds in growth medium, and were then added to the parasites. The in vitro growth inhibition tests were repeated 3 times, and the data represent the average of these experiments. Drug concentrations of CLT, KC and CP which were suppressive, but not destructive to the parasites, were prepared as described above, and applied simultaneously to the cultured parasites. The calculation of IC50 values was determined by interpolation after curve fitting.

Viability tests

After 4 days, the viability of the parasites exposed to the different drug concentrations was examined (Bork et al. 2003 b).

Morphological studies

For the transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the standard Araldite embedding method was applied (Robinson et al. 1985) as described previously (Bork et al. 2003 a,b).

RESULTS

In vitro growth inhibition assay of each drug and drug combination test

Growth inhibition of 100% was obtained with 30 μM CLT in B. bigemina, 60 μM CLT in B. bovis, and with 100 μM KC and 1000 μM CP in both parasites (Table 1). Babesia bigemina was more susceptible to CLT and CP, while B. bovis was found to be more sensitive to KC. It was proven that 5% DMSO (in its highest applied concentration in the in vitro cultured parasites) did not influence parasitic growth and multiplication, as determined by light microscopy (Tables 1 and 2).

Furthermore, we performed drug combination experiments in order to evaluate possible synergistic or antagonistic effects (Table 2). The simultaneous application of CLT/KC, CLT/CP or CLT/KC/CP significantly enhanced the killing efficacy in both parasites. In marked contrast, in B. bigemina, the combination of KC/CP caused only 37·5% inhibition, compared to 32% and 48% respectively, when KC and CP were administered alone.

Morphological changes in TEM

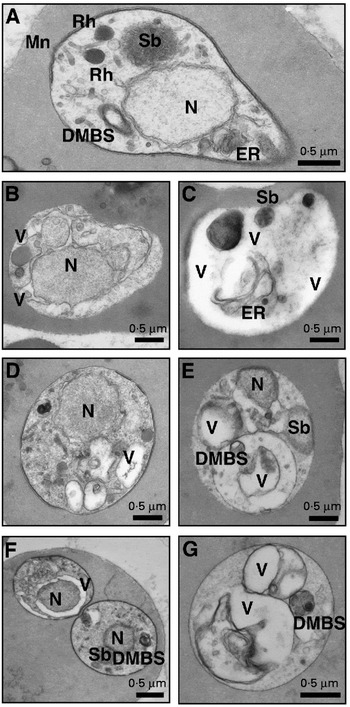

The changes to B. bigemina (Fig. 1) and B. bovis (Fig. 2) caused by CLT (B, C), KC (D, E) and CP (F, G) were examined in TEM after 1 day of drug exposure. Extensive vacuolization occurred in the parasitic cytoplasm, while the spherical body, the double membrane-bounded structure, and the parasitic membranes remained intact until the complete destruction (Fig. 1B–G; Fig. 2B–G). Damage could also be observed in the cytoplasm of parasites out of the host cells (data not shown). The host red blood cells were not affected by the drugs or by the solvent as determined in light microscopy and in TEM.

Fig. 1. TEM of Babesia bigemina. Control (A). Treatment with 60 μM CLT (B, C), 100 μM KC (D, E), and 1000 μM CP (F, G). N, Nucleus; Sb, spherical body; Rh, rhoptry; Mn, mitochondrion; DMBS, double membrane-bounded structure; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; V, vacuole.

Fig. 2. TEM of Babesia bovis. Control (A). Treatment with 60 μM CLT (B, C), 100 μM KC (D, E), and 1000 μM CP (F, G). N, Nucleus; Rh, rhoptry; Mn, mitochondrion; DMBS, double membrane-bounded structure; V, vacuole.

DISCUSSION

The efficacy of CLT, KC and CP was tested against the in vitro growth and multiplication of B. bovis and B. bigemina. The destructive effects to bovine Babesia spp. required relatively higher drug concentrations as compared to those for B. equi and B. caballi (Bork et al. 2003 b). The tolerance of both bovine parasites to CP was higher compared to those in the equine Babesia parasites, while their sensitivities against KC were similar to B. caballi. In CLT, B. bigemina and B. equi have identical sensitivity (30 μM), while 60 μM had to be applied in B. bovis. The inhibitory effect of CLT on the in vitro growth of P. falciparum was demonstrated at 2 μM (Tiffert et al. 2000), while 20 mg/kg applied orally to humans suffering from sickle cell anaemia, caused an inhibition of the Gardos channel (Brugnara et al. 1996). Moreover, 10 μM CLT reduced recovery of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) cells (Ito et al. 2002). KC destroyed T. cruzi at 1 μM (Lazardi, Urbina & De Souza, 1990), and CP could clear T. gondii between 10 and 100 μM (Zuther et al. 1999). Compared to the IC50 value of the already well-established drug imidocarbdipropionate (1·646 μM) (Rodriguez & Trees, 1996), the IC50 values of CLT, KC and CP were found to be higher, probably indicating a lower sensitivity of the tested parasites.

The principal aims of drug combinations are anchored in evaluation of combination compounds and also in delay of resistance phenomena. The combination of KC with allylamine terbinafine produced synergistic effects on intracellular amastigote proliferation of in vitro cultured Leishmania amazonensis (Vannier-Santos et al. 1995). In combination with benznidazole, KC enhanced the efficacy of chemotherapy of T. cruzi in vivo (Araujo et al. 2000), and CLT was found to be synergistic with mefloquine (Tiffert et al. 2000). Therefore, the tested compounds hold much promise for combined application in the future.

In conclusion, the potent growth inhibitory efficacy of CLT, KC and CP was clearly demonstrated against B. bovis and B. bigemina, when applied alone or moreover in combinations.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and by a grant from The 21st Century COE Program (A-1), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

References

REFERENCES

Table 1. Actual parasitaemia (p%), growth inhibition (inh.%) and IC50 values of CLT, KC, and CP in Babesia bigemina and B. bovis

Table 2. Actual parasitaemia (p%), and growth inhibition (inh.%) of combined applications of CLT, KC and CP in Babesia bigemina and B. bovis

Fig. 1. TEM of Babesia bigemina. Control (A). Treatment with 60 μM CLT (B, C), 100 μM KC (D, E), and 1000 μM CP (F, G). N, Nucleus; Sb, spherical body; Rh, rhoptry; Mn, mitochondrion; DMBS, double membrane-bounded structure; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; V, vacuole.

Fig. 2. TEM of Babesia bovis. Control (A). Treatment with 60 μM CLT (B, C), 100 μM KC (D, E), and 1000 μM CP (F, G). N, Nucleus; Rh, rhoptry; Mn, mitochondrion; DMBS, double membrane-bounded structure; V, vacuole.

- 24

- Cited by