Article contents

- Abstract

- INTRODUCTION

- USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF CE

- SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY OF ULTRASOUND AS A DIAGNOSTIC TEST

- USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE TREATMENT OF CE

- USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF AE

- COMMUNITY-BASED ULTRASOUND MASS SCREENING SURVEYS

- ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN COMMUNITY-BASED SURVEYS AND TREATMENT

- THE EDUCATIONAL IMPACT OF MASS COMMUNITY-BASED ULTRASOUND SCREENING SURVEYS

- THE VALUE OF ULTRASOUND IN CONTROL PROGRAMMES FOR CE AND AE

- References

Application of ultrasound in diagnosis, treatment, epidemiology, public health and control of Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 March 2004

- Abstract

- INTRODUCTION

- USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF CE

- SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY OF ULTRASOUND AS A DIAGNOSTIC TEST

- USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE TREATMENT OF CE

- USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF AE

- COMMUNITY-BASED ULTRASOUND MASS SCREENING SURVEYS

- ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN COMMUNITY-BASED SURVEYS AND TREATMENT

- THE EDUCATIONAL IMPACT OF MASS COMMUNITY-BASED ULTRASOUND SCREENING SURVEYS

- THE VALUE OF ULTRASOUND IN CONTROL PROGRAMMES FOR CE AND AE

- References

Abstract

The last 30 years have seen an impressive use of ultrasonography (US) in many fields of veterinary and clinical medicine and the technique is being increasingly applied to a wide variety of parasitic infections including the cestode zoonoses Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis. US provides real-time results which are permanently recordable with a high resolution and diagnostic accuracy. These properties, coupled with the clinical value of the images obtained and the non-invasive nature of the test which is safe, require no special patient preparation time; it is easy to operate and this has resulted in the establishment of US as the diagnostic technique of choice for cystic (CE) and alveolar (AE) echinococcosis. The lack of ionizing radiation and side-effects mean that examination times are not restricted. The hand-held probes facilitate what amounts to a rapid, bloodless non-invasive laparotomy, enabling a search from an infinite number of angles for lesions producing information on their number, size and type of cysts, their location and clinical implications. Such clinical information has facilitated the development of treatment protocols for different cyst types. Less invasive surgical techniques, such as US guidance for PAIR (Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Re-aspiration), PAIRD (PAIR plus Drainage) or PPDC (Percutaneous Puncture with Drainage and Curettage) are also possible. Longitudinal US studies have facilitated monitoring the effects of the outcome of treatment and chemotherapy. Portable ultrasound scanners which today weigh as little as a few pounds, powered by battery or generators have facilitated the use of the technique in mass community-based screening studies. The majority of these studies have been conducted in remote, low socio-economic areas where there were few, if any, hospitals, veterinary facilities, schools or trained personnel. The surveys led to the discovery of unexpectedly high prevalences of CE and AE in asymptomatic individuals of endemic areas and especially amongst transhumant or nomadic pastoralists living in various parts of the world. Screening for CE and AE is justified as an early diagnosis leads to a better prognosis following treatment. The application of US in field and clinical settings has led to a better understanding of the natural history of CE and AE and to the development of a WHO standardized classification of cyst types for CE. This classification can be used in helping define the treatment options for the different cysts found during the surveys, which in turn can also be used to calculate the public health cost of treating the disease in an endemic community. The case mix revealed can also influence the specificity (particularly proportions of cyst types CE4 and CE5 and cystic lesions – CL) of US as a diagnostic test in a particular setting. Community based US surveys have provided new insights into the public health importance of CE and AE in different endemic settings. By screening whole populations they disclose the true extent of the disease and reveal particular age and sex risk factors. Through the treatment and follow-up of all infected cases found during the mass screening surveys a drastic reduction in the public health impact of the disease in endemic communities can be achieved. Educational impacts of such surveys at the national, community and individual levels for both professional and lay people are beginning to be appreciated. The translation of the information gained into active control programmes remains to be realized. In areas where intermediate hosts, such as sheep and goats, are not slaughtered in large numbers mass US screening surveys to determine the prevalence of CE in livestock has proved possible. Longitudinal studies in such intermediate hosts would reveal changes in prevalence over time, which has been used as a marker for control success in other programmes. Mass US screening surveys in an ongoing control programme in Argentina has demonstrated the early impact of control in the human population and identified breakthroughs in that control programme. Mass US screening surveys must adhere to the highest ethical standards and the outcome of surveys should result in the application of appropriate WHO recommended treatment options for different cyst types. Follow-up strategies have to be in place prior to the implementation of such surveys for all infected individuals who do not require treatment and for all suspected, but not confirmed, cases found during the surveys. The use of US in community screening surveys has revealed the complexity of ethical issues (informed consent, confidentiality, follow-up, detection of lesions that are not the focus of the study etc) and also provided real solutions to providing the most ethical guidelines for the early detection and treatment of CE and AE.

Keywords

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- © 2003 Cambridge University Press

INTRODUCTION

Cystic and alveolar echinococcosis (CE and AE) in humans results from infection with eggs released from carnivorous mammal definitive hosts infected with the adult parasites Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis respectively. CE exists in a synanthropic cycle with a broad geographical distribution occurring on all the inhabited continents. AE occurs largely in sylvatic cycles and is restricted to the Northern Hemisphere. The dog is the definitive host par excellence of E. granulosus and dogs are becoming increasingly recognized as the main source of human infection with E. multilocularis (Macpherson & Craig, 2000). The main predilection site of the larval stage, the hydatid cyst, in humans is the liver with between 70% (CE) and up to 100% (AE) of the cysts occurring in this organ. After oral egg ingestion the natural history of the metacestode stage is extremely variable reflecting a heterogeneity of susceptibility within individuals (genetic, immunological, physiological, nutritional, age and sex) and also possibly intrinsic and extrinsic differences in the parasite in different parts of the world. In general, CE is usually diagnosed at an earlier age than cases of AE (Pawlowski et al. 2001) but many CE infections never become clinically symptomatic (Frider et al. 1988; Frider, Larrieu & Odriozola, 1999; Larrieu et al. 2000). In some individuals CE cysts spontaneously degenerate and die (Romig et al. 1986). In AE, although some infections may naturally degenerate, calcify and die (Rausch et al. 1987; Craig et al. 2000; Bartholomot et al. 2002), it is thought that most infections are ultimately fatal to the host (Ammann & Eckert, 1996; Wilson et al. 1992). Biologically CE grows as distinct encapsulated cysts which are usually unilocular whilst AE behaves as a slowly growing malignant tumour. In symptomatic CE and AE cases the resultant lesions become large or invasive enough to start producing clinical signs due to pressure effects on the adjacent parenchyma and the induction of other pathological changes. Upper abdominal pain and jaundice are the most common clinical signs but they depend on the organs infested and are not pathognomonic (Pawlowski et al. 2001).

The asymptomatic nature of the infection, particularly the early stages, and the lack of production of parasite stages that can be directly detected in blood, sputum, urine or faeces restricts diagnostic options to serological or imaging techniques. From a historical point of view immunodiagnostic tests, detecting serum antibody, have a well established role in the diagnosis of CE and AE (Lightowlers & Gottstein, 1995; Schantz et al. 1995; Gottstein & Reichen, 1996). Specificity of immunodiagnostic tests for CE can be increased by using antigen-5-precipitation (arc-5-test) or immunoblotting for a relatively specific 8 kDa/12 kDa hydatid fluid polypeptide antigen (Hira et al. 1990; Porretti et al. 1999). For AE the use of purified E. multilocularis antigens, such as the Em2-antigen, the Em18-antigen or recombinant antigens II/3-10 or EM10 or others, provide diagnostic sensitivities ranging between 91% and 100%, with overall specificities of between 98% and 100% (Gottstein et al. 1993; Nirmalan & Craig, 1997; Sarciron et al. 1997). These antigens also allow discrimination between AE and CE with a reliability of 95%. Immunodiagnostic tests however provide little clinical information about the infection.

With the introduction of imaging procedures a few decades ago their provision of detailed clinical information coupled with their high sensitivity and specificity today relegates immunodiagnosis as a useful secondary diagnostic tool. Immunodiagnosis is useful to confirm the identity of the aetiological agent especially in AE infections but also for CE when no pathognomonic signs are visible (Macpherson, Gottstein & Geerts, 2000). Among the imaging procedures, ultrasound (US), computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or MRI cholangiography (MRIC) are of greatest diagnostic value for CE and AE. Imaging techniques for treatment also include percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) (Pawlowski et al. 2001). Irregularly dispersed clusters of calcifications on plain abdominal radiographs may give an indication of AE infection and X-ray is useful for bone and lung localizations of CE. This paper examines the usefulness and range of applications of US in the diagnosis, epidemiology and control of CE and AE.

USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF CE

The value of US for the diagnosis of CE was recognized in the late 1960s when the technique was fist used in the medical field (King, 1973; Vicary et al. 1977). Its introduction completely revolutionized the diagnosis of intra-abdominal CE which could previously only be diagnosed with immunological tests which had low sensitivities and specificities or by laparotomy. The early imaging techniques of X-ray could only visualize calcified cysts in the abdomen but were useful for pulmonary or bone localizations. Clinical information on the number, size, location and condition (cyst type) of the cysts was available for the first time. This information was especially useful to surgeons, and also with the introduction of benzimidazoles in the late 1970s for longitudinal studies to monitor the effect of chemotherapy (Caremani et al. 1997). The advantages of the technique were quickly appreciated by operators and patients alike. They included, its lack of ionizing radiation allowing prolonged and repeated examinations if necessary, there are no unpleasant preparations or injections, the procedure is painless, harmless, non-invasive, provides instant reproducible results which can be permanently recorded and both operational and maintenance costs are low, especially in relation to other imaging techniques. Further improvements to the technique including the development of varying frequency transducers from 3·5–7·0 MHz are helping improve the resolution and performance of US. Other developments such as colour doppler and 3D, will likely result is a greater range of applicability of the technique in many fields of medicine and veterinary medicine including parasitology a field in which US is already widely used (Macpherson, 1992). Its limitations are the relatively high initial purchase cost of the equipment, the specialized training for the operator and its inability to diagnose most extra-abdominal cysts.

The identification of different types of CE cysts prompted the description of the first classification (Gharbi et al. 1981) based on clinical cases. Other classifications were subsequently produced (Beggs, 1983; Lewall & McCorkell, 1985; Perdomo et al. 1997) but were not as widely used. With the advent of portable US scanners and their use from the mid 1980s for screening in rural communities more information on the natural history of CE was obtained and a further classification was produced (Shambesh et al. 1999). A detailed clinical classification was also developed for the various changes observed following treatment (Caremani et al. 1997). Subsequently reports were published with results cited using poorly defined modifications of Gharbi's initial classification. None of these studies enabled an easy comparison of the data reported and potentially valuable information was lost. In an attempt to develop a standardized classification to facilitate both the uniform reporting of results from field epidemiological studies as well as in clinical studies, conducted in different parts of the world, a WHO working group was created in 1995. The resultant standardized classification was designed to be user friendly to operators in the field or in clinical settings, follow the known natural history of CE and, perhaps most importantly, to be agreed upon by the majority of physicians and scientists working in this area of medicine. The agreed WHO standardized classification differs from Gharbi's original by introducing a cystic lesion (CL) stage and by reversing the order of CE Types 2 and 3 (Fig. 1: WHO, 2002). These changes reflect the observation in many screening programmes of CL stages which have no pathognomonic signs but which may be early undifferentiated CE lesions. They are not included as a Type of CE as they have to be further diagnostically evaluated before being classified as CE. The reversal of CE2 and CE3 is felt to more accurately reflect the natural history of the parasite and to facilitate the grouping of the different cyst types into active, transitional and inactive groups. These three clinical groups represent different evolutionary stages of the cysts and makes it possible for clinicians to evaluate standard treatment options which are currently recommended by WHO for each cyst type and which can be appropriately applied using WHO protocols (WHO, 1996, 2001, 2003). The first group encompasses CE Types 1 and 2 which are active, usually fertile cysts containing viable protoscoleces. The second group is a transitional stage, CE3 comprising cysts where the integrity of the cyst has been compromised, either by the host or by chemotherapy: such cysts may arise from CE1 or CE2 type cysts and on occasion CE2 cysts may evolve from CE3 type cysts. The final group comprises cyst types CE4 and 5 are inactive cysts which have normally lost their fertility and are degenerative.

Fig. 1. The WHO standardized classification of CE showing the three clinical groups. Adherence to this classification will facilitate similar standards and principles of treatment, which are currently recommended for each cyst type (Reproduced from WHO, 2003).

Serological studies support the view that evolutive and subsequent involutive phases occur in the natural history of CE (Daeki, Craig & Shambesh, 2000). Specific IgG4 antibody responses have been shown to be particularly associated with the evolutive phase of CE (CL, CE1 and CE2), and were therefore associated with, or could be a marker for, cystic development, growth and disease progression. IgG1, IgG2 and IgG3 responses have been found to be associated with the involutive phase (CE4 and CE5) and predominate when cysts became infiltrated or were destroyed by the host (Daeki, Craig & Shambesh, 2000).

SENSITIVITY AND SPECIFICITY OF ULTRASOUND AS A DIAGNOSTIC TEST

Although some localizations are not visible to US the test has a reported sensitivity and specificity for abdominal localizations of between 93–98% to 88–90% and 93–100% for cases diagnosed in Italy and South America respectively (Caremani et al. 1997; del Carpio et al. 2000). Since US is able to visualize internal structures of the cysts this provides secondary or additional diagnostic information. This information can increase the specificity of the test by ruling out other aetiologies that result in space occupying lesions. The following US images of space-occupying lesions in the liver are considered to be pathognomonic diagnostic signs of CE due to E. granulosus (Fig. 1). (1) Unilocular anechoic lesions which are round or oval with a clear well defined wall (laminated membrane), double line sign (laminated membrane and pericyst). Such cysts may or may not contain small dense mobile echoes, snow like inclusions (these are floating broodcapsules which are often called hydatid sand). Classification – CE1 (WHO, 2003). (2) Multivesicular or multiseptated cysts with a wheel like appearance – CE2. 3. Unilocular cysts with daughter cysts which may present with a honeycomb appearance – CE2. Cysts with floating laminated membranes which may also contain daughter cysts – CE3.

As specificity is a property of the US diagnostic test it will vary if the case mix, the relative proportions of cyst types, reported in different studies varies, especially the proportion of CE4, CE5 and CLs found (Macpherson & Milner, 2003) (Fig. 2). The use of the standardized US classification (WHO, 2003) (Fig. 1) for CE is essential to help determine the case mix and hence the specificity of US as a diagnostic test. The use of different classifications could substantially vary the specificity of US.

Fig. 2. The case mix of different cyst types reported in four different studies. Cysts that require confirmation by diagnostic tests other than just by US alone comprise approximately 50 per cent of all cases seen. For CE types CE4 and 5 US diagnosis is very suggestive of CE. Data from China (n=316) (Schantz & Ito, unpublished), Argentina (n=186) (Pelaez et al. unpublished), Libya (n=279) (Shambesh et al. 1999) and Morocco (n=131) (Macpherson et al. unpublished).

The sensitivity of secondary serological diagnostic tests appears to vary with different CE types (Table 1). The more recently developed ELISA tests show very close correlations with CE types 1, 2 and 3 which have pathognomonic signs on US. Positive serological tests particularly help in the interpretation of CL (early CE cases?) which have no pathognomonic signs on US and also with CE4 and CE5 cyst types which have images suggestive of CE on US. Serologically-negative cases require subsequent follow-up to rule out a false negative result.

The probability of disease given the results of a test is called the predictive value of the test. The predictive value is not a property of the test itself but will vary according to the prevalence of the disease in the population studied. The positive predictive value (PPV) is the probability that the subject tested positive has the disease. The negative predictive value (NPV) is the probability that the subject tested negative is normal. As the prevalence of a disease in a population approaches zero so the PPV will also approach zero and most of the positive cases will be ‘false positives’. Since in most endemic areas the prevalence of CE and AE is less than 5·0% (Table 1) false positives may be an important problem to consider. Conversely the NPV will be very high at low prevalence and there will be few ‘false negative’ results.

Epidemiological data on the risk factors for CE or AE for particular socio-economic or socio-cultural settings together with dog/wild canid-human-livestock interactions in given endemic settings also play a role in the differential diagnosis of the disease (Frider, 2002). In high risk communities where the prevalence is fairly high most space-occupying lesions may be considered as cystic until ruled out using diagnostic tests.

USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE TREATMENT OF CE

The ability to visualise the number, size, location and internal structure (CE type) of intra-abdominal cysts by US provides clinical information necessary to the clinician and surgeon to determine the best course of therapy. Different cyst types are suggestive of different treatment approaches (WHO, 1996, 2001, 2003; Pawlowski et al. 2001). Using the WHO standardized classification (WHO, 2002) group 1 cysts are active and usually contain viable protoscolices and would always require chemotherapy in addition to surgical intervention. CL cysts that are serologically confirmed together with CE1 and some CE2 cases lend themselves to be treated by a technique introduced in 1986 of a minimally invasive surgical approach known as PAIR (Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Re-aspiration). PAIR compliments or replaces more invasive surgical treatments (Ben Amor et al. 1986a,b). The safety and effectiveness of PAIR, the percutaneous drainage of abdominal cysts, has been demonstrated by the publication of numerous articles detailing over 2000 cases (WHO, 2001). Prior to the introduction of US this procedure was prohibitively risky and ruled out because inter alia of the risk of secondary hydatidosis due to the spillage of viable protoscolices, anaphylactic shock and the lack of visual information on the cysts location, number or condition. The use of US has facilitated a number of modifications to the basic PAIR technique such as PAIRD, where the catheter is temporarily left in for drainage or PPDC (Percutaneous Puncture with Drainage and Curettage) if numerous large daughter cysts are present (CE2 cysts) (WHO, 2003). Patients with CE3 (transitional cysts – Group 2), CE4 and CE5 (inactive cysts – Group 3) cyst types may require only observation. Decisions on this will vary from patient to patient and the clinician should carefully consult the WHO treatment guidelines (WHO, 1996, 2001).

USE OF ULTRASOUND IN THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF AE

US has been used for many years for the diagnosis of AE (Didier et al. 1985; Choji et al. 1992). A PNM classification for the staging of AE has been developed (Pawlowski et al. 2001). Since primary lesions of AE occur in the liver, the sensitivity and specificity to detect AE lesions is high and in community-based studies was found to be 84% (Craig et al. 1992) and 96% (Bartholomot et al. 2002). Serological back-up tests are required for AE in most instances to confirm the aetiology of the lesions detected by US. Early AE lesions present as hyperechoic adenoma-like nodules and have no pathognomonic signs (Fig. 3). Similarly, later forms may present as nodular hyperechoic well limited lesions which are also difficult to identify with certainty by US alone. Advanced lesions may have a central necrotic hypoechoic area surrounded by a parasitic hyperechoic area. A number of AE metacestodes die at an early stage of infection (Gottstein et al. 1987; Rausch et al. 1987) and non-pathognomonic hyperechoic punctate calcified lesions may be found in community based US surveys in patients who are serologically positive (Craig et al. 1992; Bartholomot et al. 2002) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. US appearance of early (A), evolutive (B), late (C) and nodular calcified lesion (D) of AE. Early lesions have a small well defined angioma-like hyperechoic appearance (A) which may develop into a larger lesion (B) and then may eventually evolve into a lesion with a central necrotic hypoechoic area surrounded by hyperechoic parasitic tissue (C). Punctate calcifications in patients who are serologically positive for AE may represent abortive AE forms. Such calcified structures may be single, multiple and sometimes arranged in a circular arrangement.

US is also useful for the assessment of the efficacy of long-term chemotherapy with benzimadazoles (WHO, 1996; Pawlowski et al. 2001). Focally directed US guided therapies for AE are currently being investigated (Wen Hao, personal communication).

COMMUNITY-BASED ULTRASOUND MASS SCREENING SURVEYS

With the development and introduction of portable US scanners, which today can weigh as little as a few pounds, US has become the instrument of choice for mass community-based screening surveys in many parts of the world. The strengths of US over immunodiagnostic test(s) for the primary screening of CE and AE, which has been the test of choice for many decades (Craig, Rogan & Allan, 1996) are numerous and include: (1) US has a greater sensitivity and specificity than serology, as demonstrated in surveys for CE where both techniques were used concurrently (Mlika et al. 1986; Macpherson et al. 1987; Frider et al. 1988; Barbieri et al. 1994; Larrieu et al. 1994; Cohen et al. 1998) and for surveys for AE (Craig et al. 1992; Bartholomot et al. 2002). (2) US provides in the majority of cases, in a single-examination diagnosis, the clinical information necessary for decisions on appropriate treatment or follow-up. (3) US results are produced instantly facilitating early counselling. (4) Up to 40 people an hour can be screened. (5) The painless, non-invasive nature of US provides a favourable technique for screening the whole community, including young children, providing accurate age/sex prevalence data. (6) US is cheap to perform per diagnostic test. (7) The ability to demonstrate cysts on the video display unit of the US scanner can play an important educational role, particularly amongst peoples who have difficulty conceptualizing a cyst in the liver. The impact of this visualization of illness usually encourages participation in mass surveys and can have a profound effect on community members.

Screening, particularly when many thousands of individuals are involved, is expensive and the main endemic foci of CE and AE are located in low socio-economic areas. The screening technique must therefore be as cheap as possible and US facilitates this goal. Whether secondary diagnostic techniques such as serology or miniature X-ray are used simultaneously is debatable. Prior to the introduction of US, screening surveys were conducted by immunodiagnostic test(s) only (Craig, Rogan & Allan, 1996) and in some surveys for CE in South America this was supplemented with X-ray to detect pulmonary cysts (Schantz, Williams & Riva Posse, 1973; Purriel et al. 1974). In an early US study, conducted between 1984 and 1986, in Uruguay, 84 (1·4%) out of 6027 people screened by US were positive for CE whereas concurrent X-ray examination revealed no cases of pulmonary cysts in 3593 people studied (Perdomo et al. 1988). Recently a screening survey used concurrent US, serological and X-ray diagnostic tests (Moro et al. 1997) but the cost effectiveness of this approach was not studied. Most of the screening programmes conducted so far have been in collaboration with sophisticated laboratories with the goal to examine prevalence rates in endemic foci usually preselected due to high surgical incidences being reported. Such surveys have used more than just US for screening and cost[ratio ]benefit analyses have yet to be performed. Indeed the cost[ratio ]benfit of using a screening technique in addition to US needs evaluation. It can be argued that community-based prevalence surveys for CE should use US alone, with serology and/or other imaging techniques being used only for confirmation of suspected cases. The combined use of US with serology is only justified if serologically positive but US negative cases are carefully followed-up. This was done in a study in Uruguay where 2 out of 8 serologically positive but US negative individuals were subsequently found to have CE. One of the individuals had a pulmonary cyst detected by X-ray and the other a liver cyst detected by CT (Cohen et al. 1998). The greater sensitivity and specificity of serology for AE and the difficulty of differentiating many AE lesions from other hepatic space occupying lesions make a combination of the two tests desirable for mass screening surveys for AE.

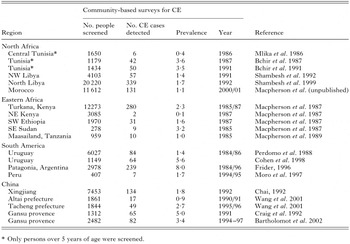

US surveys have greatly increased our understanding of the public health importance of CE and AE in large areas where the disease was previously poorly documented (Table 2). US screening in endemic areas can be justified as diagnosis of asymptomatic and early stages can lead to a better prognosis following treatment. Early detection and treatment of AE has been shown to significantly improve survival time (Bresson-Hadni et al. 1994; Sato et al. 1997).

The lack of medical, educational and veterinary facilities coupled with neither sanitation nor safe piped water provides ideal conditions for the survival and propagation of CE and AE in nomadic or transhumant pastoral communities (Macpherson, 1994). The lack of trained personnel or facilities, particularly abattoirs coupled to no dog control or dog treatment programmes in such areas allows the parasite to proliferate unchecked and there is invariably no recognition of the public health importance of the disease. A number of different regions of the world serve as clear examples of the prior lack of knowledge of CE and AE in such low socio-economic areas. For example, CE was unknown in Africa South of the Sahara until just over 45 years ago when Wray (1958), a surgeon working in Kitale, a small town south of Turkana District, in north-western Kenya, published the first reports of CE amongst the nomadic Turkana people. Over a decade later Schwabe (1964) re-examined the records and estimated that the annual incidence of the disease in these peoples was over 40 per 100000 per annum. With the introduction of surgical facilities within the District this estimate was revised upwards. The first serological screening surveys conducted by French & Nelson (1982) and later US mass community-based surveys conducted by Macpherson et al. (1987) confirmed that the people living in the District had the highest known prevalence of CE anywhere in the world. Prevalence increased with age and was twice as common in females, with almost 16% in women over 50 years of age infected (Fig. 4) (Macpherson et al. 1989). The high prevalence was also recognized to exist in all the contiguous areas occupied by nomadic pastoralists, including southwestern Ethiopia (Fuller & Fuller, 1981; Lindtjorn, Kiserud & Roth, 1982) which was confirmed by community-based mass US surveys (Macpherson et al. 1989; Klungsoyr, Courtright & Hendrickson, 1993), southern Sudan, northeastern Uganda (Owor & Bitakiramire, 1975) and in northern Tanzania (Macpherson et al. 1989) (Table 2).

Fig. 4. Age sex prevalences of CE in Turkana, Kenya (left) and AE in Gansu, China obtained from US mass community screening surveys (data from Macpherson et al. 1987; Craig et al. 2000).

Similarly mass US screening surveys among transhumant pastoral people in north west China have confirmed the high prevalence of CE amongst the predominantly Mongolian (2·7%), Kazakh (0·9%) (Wang et al. 2001) and Tibetan pastoralists (1·0%) (Bai et al. 2002). US mass screening surveys have also been carried out for E. multilocularis in an endemic agricultural mainly Han Chinese community in South Gansu (Zhang County) in central China where a US prevalence of 5·0% was reported (Craig et al. 1992). The extent of the high prevalence area has been further investigated by more recent combined US and serological screening surveys in Zhang and Puma Xian counties in Gansu Provence which resulted in a US prevalence of 3·4% (Bartholomot et al. 2002). In both of these screening surveys a number of persons exhibited small calcified hepatic lesions and were also seroreactive for E. multilocularis antibodies suggesting abortive AE infection (Craig et al. 1992, 2000; Bartholomot et al. 2002). US screening surveys also reveal the prevalence of other asymptomatic abnormalities in the abdomen and in the latter survey at least one abnormality was found in 25·3% of 2482 volunteers screened. The discovery of the existence of other abnormalities requires reporting and treatment, if indicated.

The long incubation periods of many months to years for CE and 5–15 years for AE (Ammann & Eckert, 1995) coupled with the asymptomatic nature of the majority of infected patients (Frider, Larrieu & Odriozola, 1999; Pawlowski et al. 2001) means that mass screening surveys will detect patients at an earlier age and development of the parasite. This is considered a prerequisite for effective treatment and management of AE (Pawlowski et al. 2001) and earlier detection of smaller CE cysts will normally result in a better prognosis. Mass prevalence studies by US have shown that infection with CE and AE is common at an early age and increases with time (Fig. 4).

The mean age of AE patients in populations where screening has not been carried out is high being 53 years in Alaska (Wilson & Rausch, 1980) and 55 years in Switzerland (Gloor, 1988). In screened populations the age at diagnosis was 39·3 years in Gansu, China (n=149) (Craig et al. 1992; Bartholomot et al. 2002). In Hokkaido Japan, where there is an active immunodiagnostic mass-screening programme with US (or other imaging techniques) providing a confirmation of diagnosis in positive cases (e.g. Sato et al. 1993), the mean age at diagnosis was 43 years (n=124) (Sasaki et al. 1994). As for CE, mass screening surveys for AE should detect early infections which have a better prognosis following treatment and will therefore help to reduce the public health impact of the disease.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN COMMUNITY-BASED SURVEYS AND TREATMENT

Ethical considerations tend to centre around risks, benefits, and probabilities. One significant benefit of screening surveys for AE and CE is the detection of parasitic lesions at an earlier developmental stage. For individual participants, this enhances a good prognosis following treatment, may reduce mortality and also long term sub-clinical morbidity for patients with either or both AE and CE. This is a strong ethical justification for conducting screening surveys in all areas where hospital surgical records indicate that high prevalences of AE or CE are suspected. Additionally, such surveys are justifiable in low socio-economic areas such as transhumant or nomadic areas where there are few hospital or diagnostic facilities, but where epidemiological conditions suggest that transmission opportunities would facilitate the existence of high prevalences of AE and CE.

Ethical guidelines require that participants be informed of the possible risks of participation. The risks of US surveys for AE and CE are small but they include the potential for stigma, and the fear arising from participants' new knowledge about being infected with AE or CE. Anecdotally, stigma has not been an issue in these sorts of studies, and it is perhaps counterproductive to inform participants that they may become afraid. Hence, for this specific sort of study, it may be more valuable for researchers and healthcare workers to be sensitive to these risks than to inform participants of these risks. Local physicians who will be responsible for subsequent follow-up and treatment should, if possible, be involved with the surveys to address participants anxiety related to screening, diagnosis and a positive disease finding.

The development of new surgical, chemotherapy and diagnostic techniques for CE and AE over the past 15 years has produced more options than have ever been available before to diagnose and treat these parasitic infections. The multiple diagnostic and treatment options vary considerably in their costs and availability, and some techniques will not be affordable in countries where CE and AE is prevalent. This poses the ethical issue of how to provide effective but affordable treatment. Inherent in that issue is the dilemma of how to obtain informed consent for community-based mass screening surveys. One approach has been to explain fully the goals and objectives of the screening survey to a number of respected individuals from the community to be studied, and to obtain consent on behalf of the community from them (Pawlowski et al. 2001). The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) elaborates upon several issues that must be considered in each unique setting before adopting this approach (CIOMS, 1991). Another approach used by Hall (1989) and which was recently used in mass screening surveys in Morocco (Macpherson et al. unpublished) is to use a hierarchical approach beginning with the government then moving to the chief of the district and to the head of the village. With permission of these leaders, village meetings are held to explain the study, and each individual is asked if he or she agrees to participate in his or her household. This approach provides an effective model for consent, permission and consensus (Gostin, 1991). After explaining that participation in the survey is voluntary, agreement is taken as consent to participate. Serological and other diagnostic and screening tests sometimes pose small risks, but no deleterious effects have been reported thus far with the use of US.

Clinical and field epidemiological studies must have clearly defined objectives as well as diagnosis and treatment procedures prior to the start of a survey. In a clinical setting the treatment options must be carefully explained to each participant, including the option of no treatment. Prior to community-based screening surveys decisions must be made on how to inform the community of the results of the survey, and how to inform infected patients (including asymptomatic patients). If serological screening is carried out concurrently with US, then policies must be in place to follow-up serologically positive people who are US negative. Patients may fall into several categories including those who require immediate treatment due to life threatening lesions, and treatment for symptomatic cases. Options for asymptomatic patients with cyst types CE4 and 5 and also possibly CE3 types may only require observation. Patients with CE1 and CE2 type lesions require treatment as this group have active, usually fertile (containing protoscolices) cysts. Patients with CL lesions require further diagnostic tests to confirm the identity of the lesions. The use of the WHO standardized US classification means that similar standards and principles of treatment, which are currently recommended for each cyst type by WHO, can be applied appropriately and ethically. The use of US in control programmes provides exciting new options in the control of CE, but raises the ethical question of who will cover treatment and follow-up costs, and what regimens will be cost effective in different socioeconomic settings. As stated above, it also raises the question of how to obtain informed consent effectively in different cultural contexts. It is hoped that ethical guidelines on these issues will be developed in ways that can be meaningfully applied in surveys conducted in different cultural and socio-economic settings.

THE EDUCATIONAL IMPACT OF MASS COMMUNITY-BASED ULTRASOUND SCREENING SURVEYS

There are many different ways in which mass surveys may be carried out but the preparation, implementation and subsequent follow-up of patients found to have CE or AE in community-based US surveys can be an important component of rising awareness of the public health importance of the disease amongst policy makers, local professionals and the general public in the endemic communities screened (Kachani et al. 2003). Such surveys can be used to impart important educational messages at the individual, household, community, regional and national levels. US surveys are usually appealing to rural communities where such services are not generally available but where US is recognized by its application in other fields of medicine. The qualities of US being painless, non-invasive and providing instant results are attractive to participants during such surveys and the majority of the population in a selected study area choose to be screened. In two recent surveys conducted in the mid-Atlas mountains of Morocco there was a deliberate attempt to use the surveys as an educational tool in addition to obtaining some indication of the prevalence of CE (Kachani et al. 2003). Initial educational messages were directed at local policy makers and medical, veterinary and educational professionals who lived in the endemic area to be studied. This was followed by several weeks of meetings with local community leaders who subsequently explained the objectives of the survey to the local population. Individuals who volunteered to be screened entered the study and as far as is known there were no refusals. The concept of voluntary participation, the explanation of the life cycle and clinical manifestations of the disease and its prevention were all important educational messages. The occurrence of the disease is invariably known in endemic communities but is usually very poorly understood. This often leads to a fear of the disease, especially amongst families with an infected individual who has previously undergone surgery. The surveys in Morocco began with an educational component for all who entered the study. This was done by administering a questionnaire and by showing hydatid cysts, either freshly obtained from the abattoir of from photographs. Animal cysts were recognized by almost everyone but parasite transmission and the link to human disease was mostly unknown. Next came a clinical examination to assess the ability to detect cysts by clinical palpation. This provided an educational input to physicians about the asymptomatic nature of the disease and the patients appreciated the opportunity to discuss abdominal problems they may have been experiencing with a doctor. Patients were then screened by US and 1 in 10 were randomly selected for serology. Patients found to be infected with CE were always confidentially counselled and followed up for treatment, if required. Treatment options were explained to the individual or to parents in the case of a child. Local physicians participated in discussions on the WHO guidelines for the treatment of CE and all cases were fully discussed providing an educational element for the local doctors. The over 1% US prevalence found sent an important message to the local politicians about the importance of the disease and local leaders made calls for a control programme. The high prevalence provided the impetus for discussions on the requirement for a national control programme and was taken up at the highest levels. US mass community-based screening programmes therefore can play many different roles in endemic communities.

In some rural populations, with poor educational standards and access to health facilities the concept of a disease can be abstract. In such settings it is very difficult to imagine a cystic lesion inside the liver. This abstract concept turns to an objective concept of illness, watching the image on the video display unit (VDU) of the US scanner. In many communities. the visualization of cysts on the VDU enhances participation, trust and general agreement by participant in the ability of the technique to find disease should it be present. The visualization of the presence of a liver cyst in his son was very important for a Chief of a Mapuche tribe from Patagonia who subsequently facilitated the screening of more people than was originally planned and overcame the skepticism of the people with the survey (Frider, personal communication).

THE VALUE OF ULTRASOUND IN CONTROL PROGRAMMES FOR CE AND AE

Mass US surveys identify most of the asymptomatic and symptomatic CE and AE cases in the communities studied. For example, in a recent study on AE in central China up to 92% of people in some villages were included in the study which moved from village to village after a single screening period (Bartholomot et al. 2002). The ability to screen large numbers of people has been demonstrated in Libya (Shambesh et al. 1999) and Morocco where over 20000 and 11000 people respectively were screened, the latter in a period of less than three weeks (Macpherson et al. unpublished). The cases of CE found can be classified into different treatment groups using the WHO classification (WHO, 2003; Pawlowski et al. 2001). By combining these data with recommended WHO treatment protocols the approximate cost of treatment for the various cyst types in the communities studied can be roughly calculated. The economic cost of treatment and follow-up can therefore be estimated for each endemic setting. The identification of most of the cases can also provide an indication of the public health importance of the disease in each endemic setting and provide the medical justification for the need for an intervention programme.

Complementary data on the economic cost of the disease (CE only) in livestock would strengthen the advantages that may be gained from the introduction of a control programme. Prevalence data from livestock is usually available from abattoirs and in most CE control programmes the prevalence changes in sheep are monitored (Gemmell & Roberts, 1995). There are some areas of the world where such a surveillance system in livestock intermediate hosts is not possible. For example, nomadic pastoralists keep livestock for the more erudite reasons of cementing friendships, bride price, prestige and for milk and blood so few animals are slaughtered for meat (Macpherson, 1994). The low frequency of slaughter and the lack of abattoirs in Turkana, northern Kenya coupled to the lack of ante mortem immunodiagnostic tests stimulated a study to examine the possible role of US for the ante mortem diagnosis of CE in sheep and goats. The technique was found to be relatively easy to carry out and in a study involving 300 sheep and goats which were subsequently examined post mortem a US sensitivity and specificity of 54% and 98% were found with a positive predictive value of 81% (Sage et al. 1998). These results prompted a mass US prevalence study in 1390 goats from southern Sudan and Turkana and prevalences of 4·3 and 1·8% were recorded (Njoroje et al. 2000). These studies demonstrate that in areas where animals are rarely slaughtered US can play a role in determining the prevalence of CE infection in shall animals and for surveillance of the changes in prevalence in livestock over time.

The long incubation periods of CE and AE mean that single simultaneous cross-sectional US and risk factor studies reflect transmission conditions which pertained many years previously and may not be representative of those that exist at the time of the study. For example, sequential AE mass US screenings in Gansu, China carried out between 1994–1999 revealed that history of dog ownership, as discovered by use of a questionnaire, was an important risk factor, yet not a single dog was seen in the area during that survey period of 5 years (Craig et al. 2000). However, earlier surveys carried out in the same area between 1990 and 1991 noted a large dog population with 10% of the dogs infected with E. multilocularis (Craig et al. 1992).The dogs apparently had died out after the early surveys due to an outbreak of distemper and had not recovered. Long-term studies are thus clearly important and in this case it would have been difficult to explain the role of dogs in the transmission of the disease had the earlier studies not been conducted. Similarly, longitudinal studies using regular US screening to obtain age/sex incidence data coupled with risk factor studies will provide more relevant information on human behaviour and other important transmission factors than single point prevalence studies.

Longitudinal mass community-based US studies can also be used as sensitive markers for the detection of changes in the prevalence of CE or AE in the human population. Such surveys have been planned for monitoring the effects of control programmes in Turkana, Kenya (Macpherson et al. 1986) and also in the Andean Provence of Rio Negro in Argentina (Frider et al. 2001). In Rio Negro, a control programme was initiated in 1980 and was based on education, regular deworming of dogs with praziquantel and surveillance using arecoline and meat inspection. The programme was backed by appropriate legislation and medical assistance was provided to infected individuals (Larrieu et al. 1993, 1994). The US point prevalence in children aged between 7 and 14 years of age changed from 5·6% (CI 95% 3·2–9·9) (15 out of 268 children screened) in 1984/1986 to 1·1% (CI 95% 0·04–2·7%) (5 out of 451 children screened) in 1997/1998 (Larrieu et al. 2000; Frider et al. 2001). In the initial surveys, which detected asymptomatic carriers who may have been infected at any time prior to the US survey, 65% of cysts were CE1, 18% CE2, 12% CE4 and 6% CE5. The results indicated that children had been infected at an early age, and the cysts had been able to grow, with the mean diameter of all cysts detected being 4·7 cm. A number of the cysts had degenerated, a phenomenon that has been described to take place over a period of 18 months (Romig et al. 1986). In subsequent surveys, all cysts were CE1 and had a mean diameter of only 2·1 cm, suggesting a shorter infection-to-detection time interval which may represent a period prevalence and therefore demonstrate breakthroughs in the control programme (Frider et al. 2001). This study demonstrated the sensitivity of mass US screening surveys to detect changes in the prevalence (the rate of infections at a given point in time) of CE and regular surveys will allow incidence (the rate of new cases that are acquired during a defined time period) studies to be carried out. Changes in the annual incidence of the disease will provide very precise data on the effectiveness of the control programme and the earlier the detection of cases the earlier and more effective treatment the better the prognosis. By eliminating much of the human suffering experienced with this disease by identifying the majority of cases during the initial US surveys and subsequently through regular surveys and treatment, coupled to other control activities, could rapidly minimize the public health importance of CE in a short time period in endemic areas.

The contribution of US to our understanding of the biology, epidemiology, public health importance and control of CE and AE is evolving. It is likely that the role of US, especially in diagnosis and treatment, will increase as the technique improves in the years to come.

References

REFERENCES

Fig. 1. The WHO standardized classification of CE showing the three clinical groups. Adherence to this classification will facilitate similar standards and principles of treatment, which are currently recommended for each cyst type (Reproduced from WHO, 2003).

Fig. 2. The case mix of different cyst types reported in four different studies. Cysts that require confirmation by diagnostic tests other than just by US alone comprise approximately 50 per cent of all cases seen. For CE types CE4 and 5 US diagnosis is very suggestive of CE. Data from China (n=316) (Schantz & Ito, unpublished), Argentina (n=186) (Pelaez et al. unpublished), Libya (n=279) (Shambesh et al. 1999) and Morocco (n=131) (Macpherson et al. unpublished).

Table 1. Differences in the sensitivity of serological tests to rule in US identified cases of CE. CE4, CE5 and particularly CL cases identified by US may not be true cases of CE. A positive serological result adds further diagnostic support to the diagnosis of CE in such cases

Fig. 3. US appearance of early (A), evolutive (B), late (C) and nodular calcified lesion (D) of AE. Early lesions have a small well defined angioma-like hyperechoic appearance (A) which may develop into a larger lesion (B) and then may eventually evolve into a lesion with a central necrotic hypoechoic area surrounded by hyperechoic parasitic tissue (C). Punctate calcifications in patients who are serologically positive for AE may represent abortive AE forms. Such calcified structures may be single, multiple and sometimes arranged in a circular arrangement.

Table 2. Community-based mass ultrasound surveys for cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in different regions of the world

Fig. 4. Age sex prevalences of CE in Turkana, Kenya (left) and AE in Gansu, China obtained from US mass community screening surveys (data from Macpherson et al. 1987; Craig et al. 2000).

- 91

- Cited by