It is now well over a hundred years since Archibald Francis Steuart, in an article entitled ‘The Neapolitan Stuarts’, published in the English Historical Review, argued that ‘the story of Don Giacomo Stuardo, the second Neapolitan Pretender, is worthy of more investigation’.Footnote 1 Recent discoveries in the State Papers in London and the Stuart Papers at Windsor, as well as by Giovanni Tarantino in the National Library and parish registers of Naples, mean that we now have enough information to present the main outlines of Stuardo's story.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century it was believed that the first of King Charles II's many illegitimate children was James Scott, who was born in April 1649, publicly recognised by his father in 1662, and created Duke of Monmouth the following year. In 1862, however, documents were discovered in the archives of the Jesuits in Rome that revealed that Charles II had already fathered an illegitimate son about two and a half years earlier, in 1646. The documents were first published in English by Lord Acton in 1862,Footnote 2 and then in Italian and French in 1863–5.Footnote 3 The newly-discovered royal bastard was called Jacques de La Cloche and, according to the documents, was acknowledged secretly as his son by Charles II in 1665 and 1667, and then received privately at court in 1668.

There must have been many royal bastards in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries about whom little or nothing is known. French monarchs such as Louis XIV and Louis XV, or English ones such as Charles II and James II, might well have fathered bastard children with servants of lowly status who were sent away from court to have their babies elsewhere, and of whom we have no record.Footnote 4 It is the bastards who were recognized by their royal fathers, or born to mothers of some social standing, about whom we tend to have information. And it is this distinction that made the discovery of Jacques de La Cloche so interesting, and now makes the story of the latter's son Don Giacomo so unusual. Unlike other royal bastards who were openly recognized by their fathers, Jacques de La Cloche was only acknowledged secretly by Charles II, so that his very existence remained unknown to British historians until nearly 200 years after his death. And unlike other illegitimate royal grandchildren, those born to parents of obscure or lowly social status, Don Giacomo Stuardo was made aware by his mother of his royal ancestry, so that he spent much of his life attempting to be accepted, not just as a Stuart grandson, but actually as a royal prince.

In order to understand the significance of the short life of Stuardo's father, Jacques de La Cloche, we need to know that he entered the Jesuit novitiate of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale in Rome to train to be a priest in April 1668, and that three and a half months later Charles II sent an extremely secret letter to Gianpaolo Oliva, the Father General of the Jesuits. In that letter, dated 3 August 1668, the king stated that he wished to convert secretly to Catholicism, but that he could not trust any of the priests in England. He therefore intended to ask his son to perform the necessary ceremony once he (La Cloche) had been ordained.Footnote 5

At the beginning of 1669, however, La Cloche decided to leave the Jesuit novitiate and return to a secular life. He left Rome and moved to Naples, where he married the daughter of a minor nobleman. A few months later, in 1669, he died. His son, Don Giacomo Stuardo, was born posthumously later that same year. It so happened that the last months of La Cloche's life were documented in some letters sent to London by the English agent in Rome, who was unaware that La Cloche had been secretly acknowledged by the king and who therefore regarded him as an impostor.Footnote 6 These letters were published by Lord Acton along with the Jesuit documents in 1862 (see n. 2). La Cloche's last months were documented also in the correspondence of Vincenzo Armanni, who had been secretary to the Papal Nuncio in London. Armanni's correspondence was published at Macerata in 1674, and came to light in 1890 thanks to the researches of William Mazière Brady.Footnote 7 However, it was not until 1903 that the story of La Cloche's posthumous son Don Giacomo was discovered among the papers of Cardinal Luigi Gualterio in the British Museum.Footnote 8

Although the story of Don Giacomo Stuardo attracted little attention at the time, beyond the comment by Steuart already mentioned, the short life of Jacques de La Cloche became the subject of several articles shortly before the First World War. Gordon Goodwin summarized what was known about him for the second edition of the Dictionary of National Biography in 1908,Footnote 9 Andrew Lang devoted two articles to him in 1903 and 1909,Footnote 10 followed by a third for the eleventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1911.Footnote 11 And Arthur Stapylton Barnes attempted in 1912 to show that La Cloche was the man in the iron mask.Footnote 12 Further articles followed during the course of the twentieth century,Footnote 13 culminating in the two most recent, both published by Giovanni Tarantino in 2004. The first appeared in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography;Footnote 14 the second, much longer, in Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu.Footnote 15 Tarantino was able to show that doubts about the authenticity of the letters in the Jesuit archives were almost certainly unfounded, and that some letters written by La Cloche himself, newly discovered in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, revealed how and why he had left Rome to live in Naples.

It is partly because we now have a good account of the life of Jacques de La Cloche that the time has come to tell the story of his son, who called himself Don Giacomo Stuardo. This has been made possible because of the chance survival of some letters written by Stuardo himself in the Royal Archives, of some letters written about him by Baron von Stosch in the National Archives,Footnote 16 as well as a manifesto that Stuardo sent to Cardinal Luigi Gualterio (which Steuart referred to in 1903), and a longer version of that manifesto that Tarantino discovered in the National Library of Naples when researching the life of Jacques de La Cloche. These documents do not cover all of Stuardo's life, so some important gaps remain. Nevertheless, they do provide us with the main outlines of the story of Charles II's eldest grandson, who lived all his life in the Italian States, and whose very existence is even now unknown to most historians of the period.Footnote 17 If Stuardo's story is unique in itself, it does at least illustrate the plight of the son of a royal bastard who was neither given public recognition nor condemned to live a life of obscurity. Stuardo's tragedy was that his father was both acknowledged (albeit secretly) by King Charles II and given documents that proved his high born birth. Stuardo had a claim that he was unable to ignore.

As far as we know, Stuardo spoke only Italian, and never learned either English or French. This might be one reason why so little is known about him today. No documents have emerged yet to show that he made any attempt to contact his Stuart relations in England, or the British and Irish Grand Tourists who visited the Italian States during his long life. He did, however, attempt to contact the exiled Stuart King James III after the latter moved his court to the Papal States in 1717, and there was a very good reason why he chose to do that. It concerned the succession to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland.

As the eldest and senior grandson of Charles II, Stuardo seems to have harboured a desire to succeed to the thrones of his grandfather, despite his father's illegitimacy and despite the fact that he (Stuardo) was a Catholic. This might seem completely unrealistic to us today, but we need to imagine how Stuardo could have viewed his chances.

In a letter dated 4 August 1668, of which Stuardo was probably aware, Charles II had informed Jacques de La Cloche, then in Rome preparing to become a Jesuit, that:

should he ever decide to give up the religious life, he could one day claim titles higher than his younger and less nobly born brother James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, or even the Crown, if he and his brother died without children and if by then the English parliament no longer barred accession to the throne by a Catholic king.Footnote 18

The only title higher than that of a duke was of course Prince of Wales, conferred on the heir to the throne. Charles II was well aware that anti-Catholic feeling in Parliament (and the country as a whole) made it politically difficult, if not impossible, at that time for a Catholic to inherit the throne, but he hoped that a policy of toleration, which he intended to introduce, might eventually change that. By 1669 Charles himself had no legitimate children, and it had become clear that Queen Catherine of Braganza would be unlikely to bear him any. James, Duke of York, had two young daughters but no son, and it was by no means certain that his daughters would outlive him. If neither Charles II nor his brother James were to have or leave legitimate children, then the next in line to inherit the throne would be Prince William of Orange and Princess Henriette Anne, married to the duc d'Orléans, both of them foreign. To prevent this happening the only option at that time for Charles II was to recognize his eldest bastard son as the Prince of Wales, and to persuade Parliament to accept him as heir-presumptive. However far-fetched this might appear, the fact remains that during the Exclusion Crisis of 1679–81 many people in Parliament were prepared to support the Duke of Monmouth as successor to Charles II, despite his illegitimacy.

A few months after receiving this letter, Jacques de La Cloche decided to give up a religious life to improve his prospects of becoming Prince of Wales, but his death in 1669 put a stop to any chances of this happening. In his will, however, La Cloche referred to the possibility. He specifically asked Charles II to give his unborn child the ‘Principato’ of ‘Gale’ or of ‘Monmus’ or of some other province that he (or the Italian notary drawing up the will) wrongly believed was customarily conferred on the ‘naturale’ sons of the king.Footnote 19

Don Giacomo Stuardo had a copy of his father's will, and might have had the original or a copy of the letter sent to his father by Charles II.Footnote 20 Under these circumstances it would have been perfectly reasonable for him to regard himself as a prince, and even to dream that he might one day become King of England.

It will of course be objected that in 1689 the Glorious Revolution and the Bill of Rights had excluded all Catholics from the throne, and that the failure of James's two daughters (Mary II and Anne) and William of Orange to have any living heirs had resulted in the Act of Settlement in 1701 and the Hanoverian Succession in 1714. Yet there were many people, the Jacobites, who remained loyal to the Catholic Stuarts rather than to the Protestant but distantly related George I of Hanover.

When James II died in France in 1701 he was succeeded as the Stuart king-in-exile by his son James III. The latter, however, was still young and unmarried. He had a younger sister, Princess Louise Marie, but if neither of them were to have children, then the Jacobite claim would pass to the Duchess of Savoy (daughter of the duchesse d'Orléans), who was the niece of both Charles II and James II, and therefore Stuardo's first cousin once removed. As the Duchess could hardly be expected to leave her husband in Turin and move to London to become Queen of England, Stuardo could let himself believe that he might one day succeed to the thrones — if only he could obtain public recognition from, and be received by, James III. And when James was obliged to leave France in 1717 and move his court to the Papal States, Stuardo realized that he might now have a chance to secure the public recognition that he so much wanted and that his father had been denied. Princess Louise Marie had died unmarried in 1712, Queen Anne had died in 1714, and the Duchess of Savoy was now Queen of Sicily, so even less likely to move to London. James III, meanwhile, was still unmarried and in delicate health. If James were now to die without having an heir, then the situation envisaged by Charles II would have come about: both Charles and his brother James II would have died, and they would have left no living children. By a convenient coincidence of timing, in July 1714 Louis XIV issued an edict in France declaring that his two officially recognized bastard sons might inherit the throne in default of legitimate male heirs, and he followed this in May 1715 with a declaration giving them the title of ‘princes du sang’. Don Giacomo Stuardo, as the eldest illegitimate grandson of Charles II, therefore might have hoped to be acknowledged as a prince and to become the Jacobite claimant. This, then, was the background to Stuardo's first approach to the Jacobite court.Footnote 21

* * *

In July 1718, when he was at Urbino, James III was surprised to receive a letter written by an Italian who claimed to be the legitimate son of a bastard son of Charles II, and who called himself ‘Principe Giacomo Stuardo’. The letter had been given by Stuardo to the Genoese Prince Vincenzo Giustiniani, who had passed it on to the Cardinal Protector of England, Filippo Gualterio, who in turn had sent it on to James III at Urbino. Enclosed with the letter was a portrait of the man who was claiming to be James's first cousin once removed. Neither the letter nor the portrait apparently has survived.

It was perfectly well known that Charles II had sired numerous bastard children, and indeed James III had known some of them personally when he was growing up at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.Footnote 22 Stuardo, however, claimed that his father was actually the first of all of Charles II's children, having been born in Jersey in 1646, more than two years before the Duke of Monmouth. As many of Charles II's bastard children had been recognized and given titles, we may assume that Stuardo hoped to be acknowledged by James III as his cousin, which would have been of enormous benefit to him in Italian society. In the short term he was asking James for financial support, but he believed that recognition would open up the possibility of his becoming the Jacobite claimant to the English throne. We do not know if he actually mentioned that possibility, but if he did he probably would have been regarded as a mad man.

When James III received this surprising letter in the remote city of Urbino he was in no position to discover whether Stuardo was genuine or merely an impostor. James was still unmarried and had no wish to introduce further complications to his dynastic isolation, particularly by acknowledging any bastard born (like Monmouth) before Charles II's marriage to Catherine of Braganza. He therefore instructed David Nairne, his secretary of the closet, to return both the letter and the portrait:

I am sending back to Your Excellency the letter from the man who calls himself Principe Stuardo and who declares himself to be the son of a bastard child of King Charles II of England. What he claims is not impossible, but the King knows nothing about him and does not wish to get involved in the matter. It appears from the letter that the man is lacking in both intelligence and money, and that he and Bayard display similar traits of madness. Therefore when Your Excellency returns the letter and the portrait of the so-called Stuardo to Prince Giustiniani, would he thank the latter on behalf of His Majesty for the discretion he has shown in not wishing to get involved with this man without clarifying the matter with His Majesty. Having done so, let the Prince do for this unfortunate adventurer whatever he in his kindness may think fit, but His Majesty has no further interest in the case.Footnote 23

Whether or not James III gave the matter any further thought it is impossible to say. But if he had chosen to do so, particularly after he had settled in Rome at the end of the following year, he could have discovered that Giacomo Stuardo was the legitimate son of Jacques de La Cloche. The evidence, as already noted, was contained in the archives of the Jesuits in Rome, in the archives of the Barberini family (now in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), as well as in the published letters of Armanni.Footnote 24

By 1719 the information about Jacques de La Cloche was 50 years old, and one might object that people could hardly be expected to have known secrets locked away in the Jesuit and Barberini family archives. Yet the existence in Italy of an unknown bastard son of Charles II was of such obvious interest that there is no reason why it should not have been known and handed down by a few members of the Society of Jesus or by the most senior members of the Barberini family. As we have seen, James III did not want to get involved, but if he had wanted to enquire about the origins of Stuardo, then or later, he might well have been able to discover the truth.

The Jesuit archives in particular contained a certificate in French given to La Cloche by Charles II recognizing him as ‘our natural son James Stuart’, to be called ‘De La Cloche du Bourg de Jersey’; a deed of settlement in French signed by Charles II giving La Cloche a pension; and a testimonial in Latin in which Queen Christina of Sweden stated that she knew that La Cloche was the natural son of Charles II. In addition, there was one letter from Charles II to La Cloche and four to Gianpaolo Oliva, the Father General of the Jesuits, in which the king also recognized La Cloche as his son, and gave him the name Henri de Rohan as a temporary alias.Footnote 25 There is no reason why these documents should not have been seen by Michelangelo Tamburini, the Father General from 1706 to 1730, who originated from Modena, where he had served as private theologian to James III's uncle.

La Cloche had become a novice at the Iesu in Rome in April 1668, but the following January had gone to Naples and returned to a secular life. In February 1669 he married Teresa Corona in Naples Cathedral, describing himself in the register as ‘Giacomo Enrico de Boveri [=Bourg?] Roano Stuardo’.Footnote 26 Shortly afterwards he was arrested by the Viceroy of Naples because he had so much money and so many jewels that he was suspected of being a counterfeiter. He was released after he sent two letters to Cardinal Francesco Barberini, the Dean of the College of Cardinals, begging him to ask Gianpaolo Oliva to vouch for his identity.Footnote 27

In June 1669, by which time his wife was pregnant, La Cloche travelled to France to see his mother. He apparently returned shortly afterwards with a considerable amount of money, though in very poor health. On 24 August he made his will in Naples, and died two days later. He was buried in the church of the convent of San Francesco di Paola, outside Porta Capuana.Footnote 28 In his will he stated that he was the son of Charles II and ‘Dona Maria Stuarda della Famiglia delli Baroni di S. Marzo’ — a lady whose identity no one has been able to establish.Footnote 29 According to Charles II himself she was ‘a young lady of a family among the most distinguished in our Kingdoms’,Footnote 30 and Stuardo would later describe her as ‘Maria Errichetta Stuardo’, an apparent reference to the king's mother (Henrietta Maria) but more realistically to his sister (Henriette Anne), the duchesse d'Orléans, who was only two years old when La Cloche was born!Footnote 31

Even if James III remained unaware of these facts, he might easily have discovered information about La Cloche's son Giacomo Stuardo, who was born posthumously in Naples on 10 December 1669.Footnote 32 According to Stuardo himself, his father had left him considerable wealth, including ‘due palazzi siti uno a S. Giovanni a Carbonara et l'altro a Capua, dirimpetto alli Gesuiti’, and 500,000 ‘denaro di ducati’ that had been transmitted from London and deposited in the Bank of Naples.Footnote 33 The first part of his life seems to have been uneventful, and he recorded years later that he lived ‘secretly in Naples’: ‘he grew up in the city of Naples under various disguises because of the need to live incognito for about 40 years, when on the arrival of the Imperial troops in Naples the said prince was forced to leave’.Footnote 34

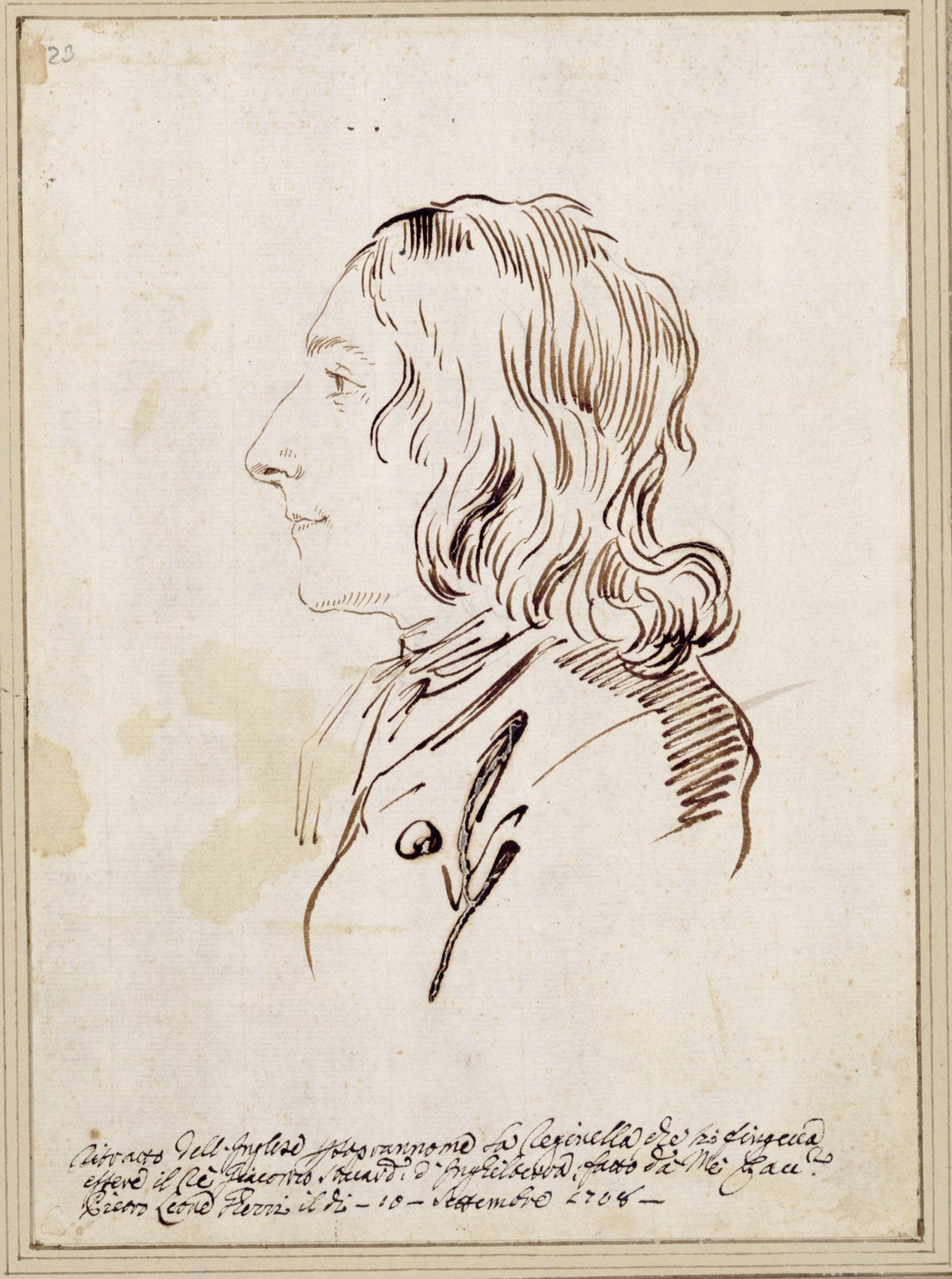

We are not told why Stuardo, by then 38 years old, had to leave Naples when the Imperial troops of Emperor Joseph I occupied the city but, given his background, we can easily speculate why this might have been. He presumably must have been pro-French and anti-Habsburg, which might explain his living ‘incognito’ while the Spanish Habsburgs ruled Naples. The accession of a Bourbon prince as King Philip V of Spain in 1700 then would have completely changed the situation for him, and perhaps encouraged him to make clear his Stuart descent and his Jacobite and Bourbon loyalties. At any rate he was in Rome by 10 September 1708, when his portrait was drawn by Pier Leone Ghezzi (Fig. 1). It carries the following interesting inscription, written by Ghezzi himself: ‘Portrait of the Englishman nicknamed La Reginella who claimed to be King James Stuart of England’.Footnote 35 It is odd that this Neapolitan who spoke no English should have been described as an ‘Inglese’, but the inscription makes it clear that Stuardo was no longer living ‘occulto’ or ‘incognito’, and now made no secret of his claim to be a grandson of Charles II.

Fig. 1. Pier Leone Ghezzi, Don Giacomo Stuardo, drawing, 24.8 × 17.8 cm (1708). Vienna, Albertina Museum, inv. 1259. © Albertina, Vienna (www.albertina.at). (Reproduced by permission of the Albertina Museum, Vienna.)

It is not known where Stuardo lived in Rome, but three years later, in September 1711, when he was 41, he married Donna Lucia Minelli della Riccia. Then, like his father, he was arrested and imprisoned (in the carceri nuove). The charge was that he was an impostor, pretending to be a grandson of Charles II. The trial apparently extended over an entire year (1711–12), and perhaps involved a consultation of the Jesuit archives. Eventually he was recognized as the legitimate posthumous son of Principe Don Giacomo Enrico, natural son of Charles II, ‘declared and acknowledged as such by a solemn diploma of his Holiness [Pope Clement XI], as evidenced by the said trial’. Following on from this legal success, Stuardo recorded, ‘at the same time another trial [was] held for the same posthumous Prince D. Giacomo in the tribunal of the Archbishop of Naples’, where he was also recognized as genuine and given certificates to authenticate his claim to be a ‘principe’.Footnote 36

With these certificates Stuardo decided to leave Rome and travel north — with or without his wife, about whom we have no further information. In 1715, now aged 45, he went to Venice, Vienna, Milan and Genoa, and he stated that in each city he was received as a grandson of Charles II and given the privileges appropriate to his rank. His absence from Naples, however, seems to have counted against him. Either now, or perhaps later, his two palazzi were occupied by (or even given to) other people ‘with no legal justification, given the absence from Naples of the posthumous Principe D. Giacomo, which happened in 1708’. At the same time, his money in the Bank of Naples seems to have been frozen.Footnote 37

It was perhaps in Genoa that Stuardo was introduced to Prince Vincenzo Giustiniani. If Stuardo had indeed lost his property and money he might well have regarded the arrival of James III and the Jacobite court in 1717 as a heaven-sent opportunity, and this would explain why David Nairne described him to Cardinal Gualterio in July 1718 as ‘lacking in both intelligence and money’.Footnote 38 Be that as it may, certain facts about Stuardo were public knowledge already by the time James III settled permanently in Rome in October 1719.

We do not know if James III now took any interest in Stuardo, and we only have a few documents that mention him during the 1720s and 1730s. There are some letters from him in the Archivio di Stato di Milano filed as ‘suppliche e lettere di Giacomo Stuardo al Governatore di Milano, al Segretario di guerra Maderno e a diversi personaggi d'alto rango’, dated 1722–3.Footnote 39 There is also ‘an account of the honour paid to him in Germany which was printed in Cologne on 6 February 1724’.Footnote 40 We then get a much more significant document, because on 30 March 1726 Stuardo obtained a certificate in Latin from Francesco Pignatelli, the Cardinal Archbishop of Naples, acknowledging that he, Principe Don Giacomo Stuardo, aged 56, was the posthumous son of Don Jacopo Enrico de Bove [sic] Stuardo, ‘Filius Naturalis Caroli Secundi Regis Angliae’, and Donna Teresa Corona of Naples.Footnote 41

Pignatelli does not seem to have consulted James III before he produced this important certificate, and we have no information about what researches he ordered before doing so. The timing is interesting, because it coincided with the separation of James III and Queen Clementina, which had divided Roman opinion.Footnote 42 The imperial or Habsburg faction among the cardinals, which included Pignatelli, sided with the queen against the king, and the imperial ambassador in Rome, Cardinal Juan Alvaro Cienfuegos, was a Jesuit who might have had access to the documents within the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu. It is possible that James III was unaware of the certificate, or that he simply took no interest in the subject. Two and a half months later Pignatelli became the Dean of the College of Cardinals, so a certificate from him was bound to carry considerable weight.

In October 1726 James III, who by then had two sons to ensure the Jacobite succession, went to live in Bologna, and while he was there Stuardo obtained official copies of his certificate in Naples.Footnote 43 James did not return to Rome until February 1729. Then, in June 1731 he went on a visit to Naples and stayed with Cardinal Pignatelli, whom he described as ‘a mighty good man’ who ‘expressed a dale of affection for me’.Footnote 44 If, therefore, James was not already aware that Stuardo was his cousin, this visit would have been an occasion when he easily might have been told.

It seems that Stuardo was by this time living in Genoa,Footnote 45 and on 8 May 1736 he sent a letter from there to James III asking to be allowed to visit him in Rome:

It is imperative for me to enter the presence of Your Majesty through the means of my letter and the attached certificate by Monsignore D. Ferdinando de Signoribus,Footnote 46 a truly religious man, who has defended my cause. Not only to have the consolatory chance to show You all my devotion and love, that I feel because of our common lineage, but also because I am in the extreme need of asking You to help me, poor and unhappy Prince, who has had to face bad Fortune despite the superiority of my lineage and the strength of my soul. I implore You, as a proof of the mercy You have towards a Prince so close to You through lineage, to send me an answer, not only as a consolation for my pains, but to glorify my Stuart blood.

He must have seen Lord Inverness, who lived at Avignon, but who had just returned to Rome (perhaps via Genoa) for a visit of three months, because he adds:

I am sure that Milord Inbernes [sic] has already presented to You my concerns and explained my pitiful condition, succeeding in this way in awakening Your natural compassion. And I hope that God will put in Your heart compassionate feelings towards me and that Your merciful answer will arrive soon to comfort me.

He finished the letter by ‘wishing Your Majesty the happiest and rightest thoughts and at the same time an endless happiness’.Footnote 47 James presumably must have discussed this letter with Inverness. He decided that he would not let Stuardo visit him, but there is evidence that he might now have taken an interest in his cousin.

In 1734 the Spanish had reconquered Naples, expelled the imperial troops of Charles VI, and granted the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to Philip V's son, Charles of Parma. In 1736, when Stuardo sent his letter, the 2nd Duke of Berwick was serving as the Spanish ambassador in Naples. Berwick was a very close friend of James III, but he was also the son of the latter's half-brother. So he was himself the legitimate son of a bastard son of James II, a man with an identical background to Stuardo, though with a very different fortune. In November 1736 he stayed for a few weeks with James III at Albano, and from February to April 1737 he stayed with him at the Palazzo del Re in Rome for three months.Footnote 48 Might the two men have discussed their cousin together? It is possible, even probable. Some years later (in 1752) the fathers of the convent of San Francesco di Paola, outside Porta Capuana at Naples, testified that by order of the ‘Sagra Congregazione di Roma’ they had exhumed ‘in this church of ours the body, or corpse, of Principe Giacomo Errico Stuardo son of King Charles the Second King of England’. They added: ‘The Duke of Berwick in the company of Count Giacomo Stella, general agent of the posthumous Principe Stuardo, came to this church of ours, as they said, that they had come to see where the King of England's son was buried’. In the presence of ‘many religious, and a number of lay persons’, the coffin was opened and the corpse examined: ‘beneath his head they found a vial and inside there was a small piece of paper on which was written ‘Giacomo Errico son of the King of England’, and they placed it in another urn, and returned him to his grave’. After this discovery, made in company with Stuardo's ‘Agente Generale’, the Duke of Berwick told the fathers of the convent ‘that he wished to celebrate a solemn funeral’. This, according to the notary who recorded the testimony of the fathers, was ‘nell'anno 1736, o 1737’,Footnote 49 precisely the years when Berwick stayed with James III at Albano and in Rome. Unless the exhumation was done against the wishes of James III, which is unlikely, we may conclude that by this time Stuardo had been accepted as a genuine grandson of Charles II.

Despite this, James III had no wish to meet or to help Stuardo, and the Duke of Berwick died in Naples in 1738. So Stuardo wrote again from Genoa on 15 August 1739: ‘As I was always proud to descend from Your Majesty's lineage, so I have Your aggrandisement at heart and I would give my life to protect it. The worst mishap I ever had was that I never succeeded in finding a shelter under the charitable shadow of Your patronage’. Stuardo added that he had been in contact with the Duke of Ormonde who, like Inverness, lived in Avignon:

The Duke of Ormonde is now helping me to enjoy this extremely important advantage; from him I received the attached letters for Your Majesty and for the Prince of Wales, Your first son. I hope that thanks to his honourable intercession You will be so clement to protect and defend me. Furthermore I hope that in consequence of Your pity God's mercy will bless You and Your sons. If I have the chance humbly to present myself to You, I will explain the deepest feelings of my heart.Footnote 50

It was probably around this time that Stuardo sent to James III an engraving by Girolamo Rossi of Caterina Fieschi Adorna, whom he described as ‘amantissima mia Protettrice’, and whom he hoped would persuade James III to send him a reply to his letter.Footnote 51 Attached to the engraving in the Stuart Papers there is the following undated prayer:

My most benign protectress, ever since the Lord God granted me the grace to know you, and revere you in this your triumphant homeland, it has pleased you with your protection and patronage always to help me and especially to grant my wishes; once again from the bottom of my heart I beseech you to grant me your most efficacious protection and sustain me on earth and in Heaven also inasmuch as I was born the grandson of Charles II King of England, and cousin of King James III. Because of this infallible truth I will acknowledge through you the justice that the King must render me, in his magnanimous heart replying to my letter enclosed when through your intercession he is inspired by the Holy Spirit (may it preserve him).Footnote 52

Neither Stuardo's letter, nor the letters from Ormonde, nor this prayer appear to have succeeded in persuading James III to receive Stuardo.

Stuardo does seem, however, to have had a lasting influence on the family of the Duke of Berwick. The documents do not reveal if the 2nd Duke had been accompanied by his wife (Catalina Ventura y Colòn de Portugal)Footnote 53 or his sonFootnote 54 when he visited the tomb of Jacques de La Cloche, but a few years later the 3rd Duke of Berwick adopted the name Stuardo instead of FitzJames. The Dowager Duchess of Berwick (second wife of the 1st Duke and mother of his children in France) complained to James III in March 1745:

the Duc de Berwick has taken the name of Stuard[o] and to see the saime familey cald by too different naimes seemes most extraordinary … I see in public papers Dom Stuardo Portugal which I am told is my grandson. I don't wonder at ther taking the name of ther mother as an heiresse …, but to change names … is very nice and choking to my mind.Footnote 55

She asked the king to write to the Duke of Berwick to insist that he keep the name FitzJames. James III replied:

I really dont see what I can do to rectify what you with reason disapprove in relation to the [2nd] Duke of Berwick's children taking the name of Stuardo. I never call them but by their own name myself, and I remember that in some Bull or Bref granted by the Pope to the Grand Prior [Pedro FitzJames de Alcantara, brother of the 3rd Duke], he would have been called Stuardo if I had not prevented it. It is certainly not their name.

James then suggested that the duchess write ‘friendly and freely’ to her step-grandson, the 3rd Duke, ‘on this subject … letting him know that I am of your opinion’.Footnote 56 She presumably did write, because the family has ever since been known as FitzJames-Stuardo.Footnote 57

We now come to the final phase of Don Giacomo Stuardo's life. In 1743, by which time he was 73 years old, Stuardo decided to return to Naples — presumably from Genoa.Footnote 58 One reason for his decision to return was that Naples was now ruled by a son of Philip V of Spain: ‘(by the grace of God) the forces of the Spanish monarchy had already returned some time since’. In order to reach Naples he had to travel via Rome, where of course James III had been living for most of the time since 1719, and when he arrived there, calling himself Principe Giacomo Stuardo, he was immediately arrested as an impostor. As he himself recalled: ‘he arrived in Rome on 11 November 1743, when he was once again arrested with all his retinue, and taken to the carceri nuove as an impostor and false prince’.Footnote 59

Liborio Michilli, the giudice criminale del Governo di Roma, seized all his possessions and confiscated all the ‘writings and documents regarding the identity and authentic royal birth of the prince’ — including the certificate of 1726 from Pignatelli, certificates Stuardo had received from Venice and Genoa, ‘a privilege of Charles II’ that had been given to his father, and ‘many other papers, and correspondence, Royal Seals, and orders’. If we assume that all these documents were genuine, we are nevertheless surprised to discover that Stuardo claimed that he was a Knight of the Order of the Thistle, which had been revived by James II in 1687 and which was regarded by the exiled Jacobites as a very great honour, in the gift of James III. The objects confiscated from Stuardo included, ‘packages which are declared to belong to the said posthumous Principe D. Giacomo, Knight of the Order of St Andrew of Scotland’.Footnote 60 This must have damned Stuardo in the eyes of both the Roman authorities and James III.

Stuardo remained in prison for three months and thirteen days, until 24 February 1744. During that time he had copies of his certificates sent to Rome from Genoa, and these were accepted as genuine by Cardinal Silvio Valenti Gonzaga, the Papal Secretary of State and a friend of James III. He was then released without a trial:

without ever having been examined, he was brought to court to hear his sentence by order of His Holiness [Pope Benedict XIV], which was to be exiled from all the territories of the Papal States, deprived of the Order of St Andrew as an impostor and counterfeiter; for which reason, in the presence of the ministers and agents, he was made to strip to his shirt, and dressed from head to toe in the clothes of a beggar sent on purpose by that court.

He was taken to the coast, put in a feluca, and sent by sea to Naples, where he arrived on 27 February. Fortunately for Stuardo, his relations came to his rescue, took him back to their house and looked after him.Footnote 61

Stuardo now set about recovering both his identity and the property he had lost since his departure from Naples in 1708. Pignatelli had been succeeded as archbishop by the pro-Spanish Cardinal Giuseppe Spinelli, and in 1744 Luigi Gualterio (nephew of Cardinal Filippo Gualterio) arrived as the new Papal Nuncio. Stuardo hoped that these two men would help him.

On 3 December 1745 the Curia Archipiscopale of Naples gave Stuardo an officially authorized copy of the certificate he had obtained from Cardinal Pignatelli in 1726. He then approached the Bishop of Cajazza, who was Archbishop Spinelli's vicar-general. On 10 April 1747 the bishop gave Stuardo a document recommending him to the charity of everyone in the archdiocese of Naples as ‘grandson of Charles the Second King of England, a follower of the Catholic faith and a zealous observer of our holy doctrine, for which he has suffered and did suffer so many travails’.Footnote 62 In the following year he obtained a notarial certificate that: ‘the said individual testified that he had visited the greatest courts of Europe, that is Rome, the courts of Germany, the Venetian Republic, the court of Genoa, and now Naples’.Footnote 63 He was now ready to take his case to court.

Employing an advocate named Don Francesco d'Amici,Footnote 64 Stuardo prepared a ‘Manifesto in which proof is provided of the identity and royal birth of Principe D. Giacomo Stuardo, posthumous son of Principe Giacomo Errico Stuardo and grandson of Charles II King of Great Britain’. This manifesto was printed and dated 7 January 1750, and contains a brief and highly selective account of Stuardo's life.Footnote 65 It explains who Stuardo's parents were and identifies the people who had known him before he left Naples in 1708. It mentions his marriage in 1711, and his first arrest and imprisonment in Rome. After a brief reference to his travels in 1715, it then jumps on to 1743, when Stuardo returned to Rome, was arrested a second time, and had all his papers confiscated by the government of Rome. These, the manifesto points out, were now, ‘in the hands of Judge Liborio Michilli’, and should therefore be examined as evidence. It then specifies the ‘assets left by the Serenissimo Principe D. Giacomo Errico Stuardo in this Kingdom of Naples’, which were the two palazzi (in Naples and at Capua) and the money deposited in the Bank of Naples, all of which he now claimed. The case was brought before the archbishop's court by Stuardo ‘free because poor’.Footnote 66

The trial, of which we have no details, lasted a year, and judgment was given on 15 December 1750, five days after Stuardo's 81st birthday. He was granted probate of his father's will, and ordered ‘to be granted possession of all the property of his supposed father’.Footnote 67 His advocate made the following comment:

this prince of whom we speak, we may say that it is a manifest miracle of Heaven that sustains him on earth to the greater glory of Holy Mother Catholic Church in Rome in the midst of so many travails and infinite calamities that if he had been a giant at this time he would be dust, we can only say that he will serve as a mirror to be admired by all literary men capable of understanding this well-founded document, and what is related above is entirely established by the Government of Rome.Footnote 68

If James III was aware of this trial it is unlikely that he took any interest in it. Perhaps James's second son, Prince Henry, Cardinal Duke of York since 1747, might have followed the fortunes of his second cousin. Either way, obtaining judgment was one thing; having it enforced seems to have been much more difficult, and nothing had been achieved more than a year later. On 10 March 1752 the 82-year old Stuardo decided to approach Luigi Gualterio. Having reminded him that his uncle had been Cardinal Protector of England, Stuardo wrote:

I would think that you are well enough apprised of a poor prince accompanied by infinite calamities and reduced to begging for bread; not for this does one lose the rank of prince, saying with the Holy Gospel that poverty does not destroy nobility, and with your profound learning and saintly mind you will judge my conduct, as it has been judged by all the courts of Europe where I have been, and by this sovereign monarch [Charles, King of Naples] (whom may God forever make happy) who commanded the tribunal of the G[rand] C[ourt] of the Vicaria by his royal despatch to do me justice and declare me sole heir of the royal Stuart blood of England, and all this was not of my doing, but of Jesus Christ, who desired to show the whole world a wandering prince; for this reason I confide in your valid patronage so that he will remember our present plight. I reverently kiss your saintly hands.Footnote 69

Stuardo attached to this letter a printed pamphlet covering four folio pages, containing copies of the Pignatelli certificate of 1726, the recommendation of the Bishop of Cajazza of 1747, and a (slightly muddled) family tree showing his descent from Charles II and stating that ‘Charles married into the house of Braganza, and had no issue, but in his youth with Maria Henrietta Stuart [had] a son, Jacques Bourg Rohan Stuart, an illegitimate son’.Footnote 70 It also included his manifesto of January 1750, together with the judgment of December of that year.Footnote 71 Unfortunately there is no indication with these papers as to how they were received by Gualterio.

There is only one more document concerning the elderly Stuardo. During 1752 a longer version of his ‘Manifesto’ was published in Naples.Footnote 72 The additional information contained within it included the 1724 publication in Cologne of the honour paid to him in Germany, and the exhumation of his father's body in 1737 or 1738. The new Manifesto also stated that Stuardo had been reduced to living in poverty in Naples since his release from prison in Rome in 1744.Footnote 73 After that there is silence. Perhaps Stuardo died later that year; perhaps he lived on in Naples for a little longer, the record of his death not having emerged yet from the Neapolitan parish registers.

In conclusion, there can be no doubt that Stuardo was the legitimate posthumous son of Jacques de La Cloche, and little doubt that his father really was a bastard of Charles II. It is the women in the story who remain mysterious. We know that Stuardo's wife was Donna Lucia Minelli della Riccia, and that his mother was Teresa Corona, but we know nothing about them. Stuardo and his wife did apparently have a son, but we do not know if his mother ever remarried, and we do not even know when the two women died. More important, we do not know the identity of Stuardo's paternal grandmother, and it seems fairly clear that even Stuardo himself had no idea who she really was. All he did was to repeat what he had been told by his mother, who herself had to rely on what she had been told by La Cloche during the short period (January to August 1669) that she had known him. No historian has been able to identify ‘Maria Stuardo della famiglia delli Baroni di San Marzo’,Footnote 74 and Stuardo evidently failed to contact any of his relations other than James III. La Cloche himself stated that his mother died in France in 1668 or 1669, and was ‘of His Ma'tie Royall Family, which nearness and greatness of Blood was the cause … that his Ma'tie would never acknowledge him [publicly] for his Sonn’.Footnote 75 And of course it was from Stuardo's grandmother as well as his grandfather that he obtained his surname.

On the evidence available to us we are likely to feel considerable sympathy for the unfortunate Don Giacomo Stuardo, and especially if we compare his life with those of the other grandchildren of Charles II, his first cousins. But the trouble is that there are gaps in his life story, beginning with his first 38 years in Naples, and continuing with his time in Rome and Genoa, and finally in Naples again. How did he pass his time; what did he do? Our knowledge comes from relatively few documents, some of them prepared by Stuardo himself in pursuit of the recognition he craved. Why, for example, did Ghezzi refer to him as ‘La Reginella’? Was it simply because his mother had been called that?Footnote 76 Was it because he lived in the Via Reginella in Rome beside the Palazzo Costaguti, near the Campo dei Fiori? Or was it because he was regarded as effeminate? Or was there some other reason? We do not know. Ghezzi's portrait perhaps makes Stuardo look a little simple, and we are reminded of Nairne's comment that he was ‘lacking in … intelligence’.Footnote 77 Might either of those be a reason why Stuardo failed to achieve any recognition from James III? Stuardo must have genuinely believed that he was the grandson of Charles II. But why did he pretend to be a Knight of the Order of the Thistle, which he obviously was not?Footnote 78 These questions remain unanswered.

What, we might ask, would have been the result if James III had openly acknowledged Stuardo as a grandson of Charles II, and consequently as his own first cousin once removed? He could hardly have given him a household appointment at the exiled court, particularly if he was simple-minded. Nor could he have afforded to grant him a generous pension. Also, the births of James III's two sons in 1720 and 1725 had put an end to Stuardo's hopes of one day becoming King of England. Yet the fact of recognition and the knowledge that he had been received by James III would in themselves have improved enormously Stuardo's prospects and standing in Italian society. So we are forced to question the motives of James III in refusing all Stuardo's humble pleas for help.

At first sight it might look as though James III was unnecessarily unkind in rejecting Stuardo's overtures. But in fact James had very good reasons for behaving as he did. The first concerns the ‘warming pan myth’. Doubts had been cast over his own legitimacy by Whig propaganda, with his enemies referring to him as the ‘pretended’ Prince of Wales in the sense of being a fraud, rather than in the neutral sense of being a claimant. It would not have been helpful to the Jacobite cause to present his enemies with the opportunity to bracket together two Stuart pretenders, one claiming to be the son of James II, the other — on the face of it extremely improbably — a grandson of Charles II, and both of them Catholics living in Italy. Nothing would have been gained, and much might have been lost.

It would have been necessary also to explain how this Neapolitan calling himself Don Giacomo Stuardo could possibly have been a grandson of Charles II. To do that would have involved identifying Jacques de La Cloche. Yet that would have been dangerous for the Stuart reputation, because Charles II had intended that La Cloche, training for the priesthood in Rome, should return to London and receive him into the Catholic Church.Footnote 79 The only documents that proved that La Cloche was Charles II's son also contained that incriminating information. The last thing that James III wanted was to damn the entire Stuart dynasty in the eyes of Hanoverian England by revealing that not even Charles II had been trustworthy. Don Giacomo Stuardo was in effect a victim of circumstances beyond his control and quite possibly beyond his comprehension.

If the story of Stuardo demonstrates the inherently difficult position of the offspring of a royal bastard of intermediate status — acknowledged secretly but not publicly —, it also reveals the vulnerability of a king in exile. Even Charles II had not been willing to acknowledge publicly his first bastard son, born many years before his marriage to Catherine of Braganza. James III, dependent on papal hospitality, was not in a position to associate himself with a man who all too easily could be dismissed as no more than a Neapolitan adventurer. And Stuardo, brought up in the Kingdom of Naples where the tradition of noble titles was very different to that in England, undermined his own case by describing himself as a prince and by implying, even if unintentionally, that his father was the son of an incestuous relationship between Charles II and his own sister Henriette.Footnote 80 From James III's point of view, Stuardo was simply an embarrassment.

There is no reason, however, to doubt that Stuardo was a grandson of Charles II, or that James III believed him to be his own cousin.Footnote 81 For a short time, from 1714 to 1720, Stuardo had reason to hope that, if publicly recognized by James III, he might become the Jacobite heir-presumptive. Thereafter he hoped that recognition would benefit him both financially and socially. Above all, he hoped that it would result in his status being acknowledged everywhere to be that of a principe, which he firmly believed himself to be. Unless he were given a Jacobite dukedom or earldom, or some lesser peerage, then in English terms he was no more than Mr Stuart or Signor Stuardo. Acceptance in Italy as a prince or principe, on the other hand, could be achieved by simple recognition, without requiring any specific territorial title. This is what he so badly wanted, and this is what he was never granted.Footnote 82