This project is exploring the long-term relationship between a Roman town — Interamna Lirenas, founded in 312 bc — and its hinterland (Bellini, Launaro and Millett, Reference Bellini, Launaro, Millett, Stek and Pelgrom2014). Since 2010 this research has involved a geophysical survey over the whole urban area (25 ha), intensive field survey across its surrounding countryside (400 ha) and a test excavation of a hitherto unknown theatre (Bellini et al., Reference Bellini, Hay, Launaro, Leone and Millett2012; Reference Bellini, Hay, Launaro, Leone and Millett2013; Reference Bellini, Hay, Launaro, Leone and Millett2014).

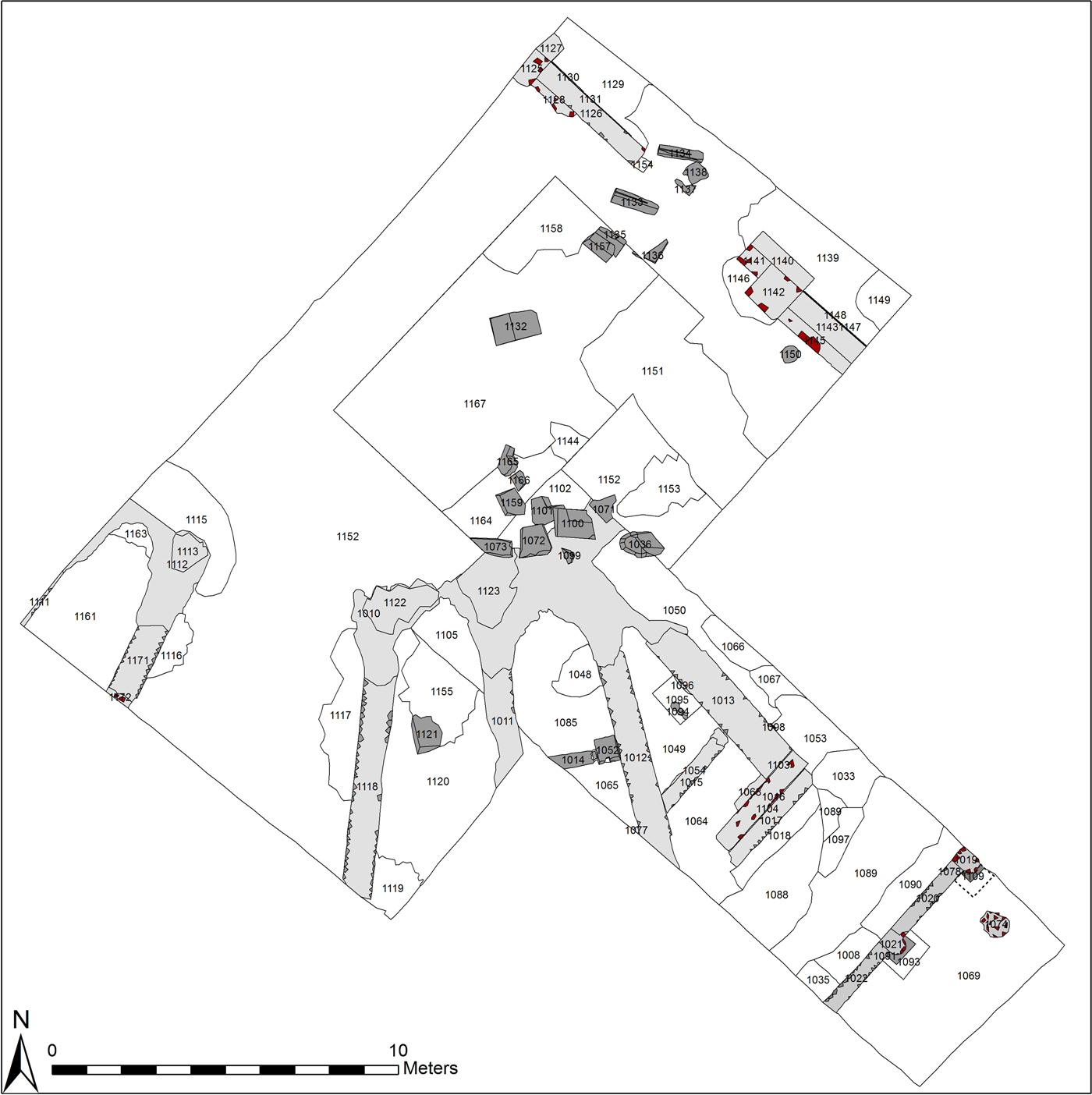

In 2014 the excavation of the theatre was extended by way of another perpendicular section (23 × 13 m) (Figs 1–2). Based on the images produced by the GPR survey last year, we expected this area to encompass more of the cavea (seating area and relative supports), a larger portion of the orchestra (the semicircular space at the centre of the theatre) and a sizeable section of the pulpitum/scaena (stage/background). Such expectations proved correct, although the excavation yielded further important details that help us understand the post-abandonment phases of the building and its state of preservation.

Fig. 1. Aerial view of the excavation (as of 2014) overlaid onto the results of the GPR survey.

Fig. 2. Plan of the excavation (as of 2014).

First and foremost, the floor of the orchestra (that is, the lowest point of the building — not including foundations, of course) is yet to be uncovered, despite the fact that our trench has reached a depth of about 1.7 m below the surface. Furthermore, although we have identified the wall of the scaena and an opening through it (that is, one of the hospitalia that allowed actors onto the main stage), the floor of the pulpitum itself is yet to be found. All of this suggests that the structure is better preserved in its lowest levels than originally assumed. As for the scaena wall, whereas the southern face was badly preserved, the northern one yielded extensive in situ remains of frescoes (two sections about 4 m in length on each side of the hospitalium). These have not been excavated, as it was deemed advisable to carry out this work in the presence of a conservator (which is planned for the 2015 season). One feature that we did not expect to discover was a gap in the disposition of the radial walls supporting the cavea: a wall is apparently ‘missing’, perhaps robbed in the post-Roman period. Given the preliminary state of our excavation of that sector (where only the plough-soil has been removed), it is still premature to make anything out of this ‘absence’, even though adjacent walls have already become clearly visible even at such a (shallow) depth.

Especially interesting is the evidence we have uncovered for an extensive and systematic spoliation process. Large blocks of limestone, in all likelihood part of the cavea originally, were found displaced and broken up — some even stacked vertically against each other (most likely for later processing). The thick layer of debris that fills the cavea appears to have been cut at some point to allow access to the structures, in accordance with a practice that is well-attested at the site for the whole modern period (in fact being exploited as if an open-air quarry). A preliminary analysis of some of the finds from contexts associated with these activities suggests a medieval origin for at least some of them. The presence of a large magnetic anomaly to the northwest (as revealed by the earlier magnetometry), taken together with the fact that several of the limestone blocks were smashed, seems to point to the existence of a limekiln nearby.

Archaeobotanical analyses were carried out on flotation samples from excavated contexts. The range of charred edible flora, of hulled wheat, pea/bean and cabbage/ mustard seed is rather limited, and consistent with much of the later prehistoric to early historic periods in Europe. The main type of cereal grain is most likely to have been emmer wheat (although further confirmation is required from the recovery of chaff fragments, or at least well-preserved grain). The other main wheat of Roman Italy was einkorn, but this distinctive, rather angular, grain does not yet appear to be present in the samples. There is currently also no evidence for barley. The co-occurrence of charred grain with fish scales, and in one case marine bivalves, strongly suggests accumulations of cooking refuse in the room in the eastern corner of the new trench. Whilst this material could derive from much later manuring of the fields, this is thought unlikely for two reasons: (a) the material occurs in two contexts and is not more widespread, and (b) both charred grain and fish scales are fragile items that are unlikely to survive in any great numbers with repeated ploughing and transportation from the topsoil down to the plough-soil base. It is more likely that the cooking refuse derives from once-stratified, more concentrated remains in Roman (?) surface middens, which may have been truncated or obliterated by later ploughing of the site.

The 2014 season has added much to our understanding of the post-abandonment phases of the building and its current state of preservation. It is not yet possible to propose a date for the abandonment of the building — or at least for the end of its use for holding spectacles — but new light has been shed on its later phases.

Acknowledgements

The project is run in collaboration with the British School at Rome and the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici del Lazio (now Soprintendenza Archeologia del Lazio e dell'Etruria Meridionale). It has benefited from the generous support of the British Academy, the Leverhulme Trust, the Faculty of Classics (University of Cambridge), the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research (University of Cambridge) and the Comune di Pignataro Interamna.