The archaeological fieldwork at Interamna Lirenas is part of an integrated research project involving geophysical prospection, field survey and excavation, all aimed at exploring the long-term development of the Roman town and its territory from its colonial origin (late 4th c. BC) well into Late Antiquity (6th c. AD) (Bellini, Launaro and Millett, Reference Bellini, Launaro, Millett, Stek and Pelgrom2014). The full coverage Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey of the urban area (in collaboration with Ghent University) and the main excavation of the roofed theatre (theatrum tectum) were brought to completion in the course of the eighth fieldwork season (2017).

The GPR survey covered another 4.7 ha, bringing the total surveyed area to about 22.7 ha. We now possess an impressively detailed plan of the town, featuring a basilica, two baths, an intra-mural sanctuary and a wide range of other public and domestic buildings still under interpretation. This plan, combined with the analysis of the ploughsoil assemblage systematically collected over the entire urban area, confirms our earlier hypotheses about the need to radically rethink the long-term development and role of Interamna Lirenas (whose peak of occupation – in both town and countryside – appears to have extended well into the 3rd c. AD: Launaro and Leone Reference Launaro and Leoneforthcoming).

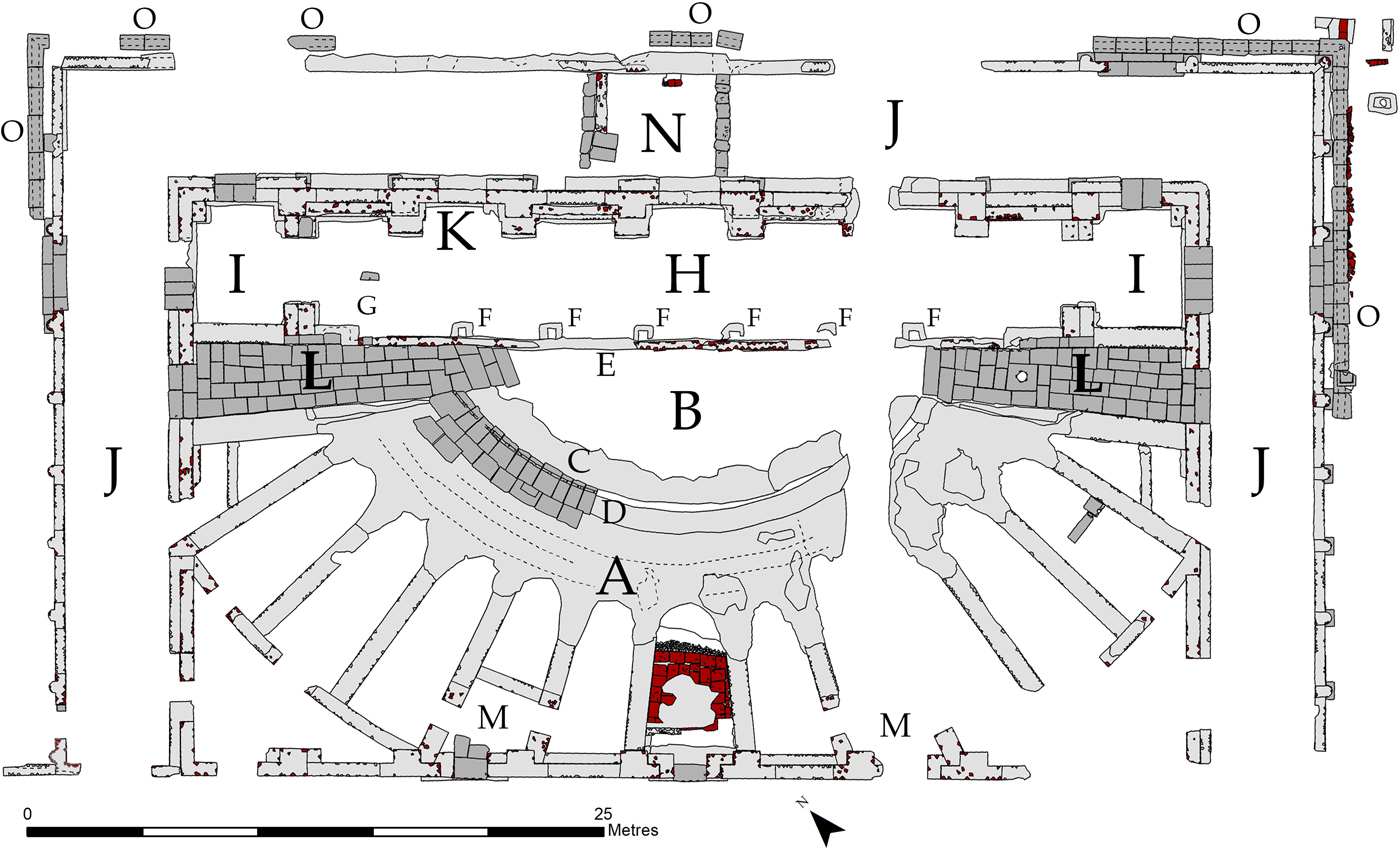

Guided by the results of earlier GPR surveys, the excavation area was extended to include the whole plan of the theatre, eventually brought to light in its entirety (Fig. 1). It is now possible to confirm some earlier hypotheses and also expound some further considerations about the architecture of the building.

Fig. 1. Plan of the excavation at the end of the 2017 season.

The cavea [A], was contained within a rectangular structure (45 m × 26 m): eight pairs of pilasters along its long sides supported tie-beam trusses spanning 24.3 m across (ca. 83 pedes), thus comparing rather favourably with some of the largest roof-spans attested in the Roman world (Ulrich, Reference Ulrich2007: 149 Table 3 and 3A), highlighting not only the clear monumental ambition of this building project, but also the significant financial effort which must have made it possible. Inside the main hall, very little remains of the orchestra [B]: buried under contexts associated with (late) activities of systematic spoliation, very few fragments of dark grey marble (Bardiglio di Carrara) are what remains of the original flooring. This space is bordered by a curved layer of thick opus caementicium (concrete), originally the setting for the slabs of the prohedria [C], the seating area reserved for magistrates and decuriones (Sear, Reference Sear2006: 5–6). Immediately behind and running parallel to it, another curved layer of opus caementicium supported the passageway (balteus) [D] separating the prohedria from the rest of the cavea: closer inspection of the surface of the eleven surviving slabs has convincingly identified traces of the barrier (podium) which further demarcated such separation.

The exploration of the stage area has confirmed how little of the proscaenium wall [E] is preserved, in fact limited to its foundations in opus caementicium and some very scant portions of the original brickwork (opus testaceum). Traces of all six aulaeum slots [F] have been identified, whose interpretation is now complemented by the identification of remains of the relative winching system [G] (two standing limestone blocks featuring round slots for the fitting of a rotatory beam). At each side of the pulpitum [H] lay one basilica [I]: these rooms (decorated with painted plaster) were themselves in direct communication with the perimeter corridor [J] by way of two doorways (as attested by the presence of square pivot sockets on the threshold slabs). Numerous marble fragments (especially veneer) and various architectural elements (e.g. a Corinthian capital) have been recovered in the pulpitum area and are probably pertinent to the collapse and/or spoliation of the second-phase architectural decoration (columnatio) of the scaenae frons [K].

The two aditus maximi [L] provided access to the orchestra and the ima cavea (lower seat rows): they are relatively well-preserved and were originally fitted with doors (as attested by the presence of square pivot sockets on the upper threshold slabs). The relative thickness of the walls bordering these two passageways might be explained with the existence of vaults supporting the two tribunalia (boxes) reserved for the magistrates presiding over the spectacles (Sear, Reference Sear2006: 6–7). It is also worth noting that the western aditus presents a circular opening (42 cm in diameter), in origin probably fitted with a manhole and leading into a vertical round chamber (90 cm in diameter) immediately underneath: this chamber (filled with debris and only explored up to a depth of ca. 1.5 m) is built in opus quadratum (local travertine) and can be interpreted as a likely access point to the (pre-existing?) sewer system below. Further access to the auditorium was made possible by way of two symmetrical stairways [M]: remains of the lower step of the western stairway have been found next to its entrance, whereas the eastern one is in fact assumed to be symmetrically laid out (most of it was removed when a deep trench was cut across the theatre as part of a systematic spoliation process: Bellini et al., Reference Bellini, Launaro, Leone, Millett, Verdonck and Vermeulen2017: 322).

The media and summa cavea (i.e. the middle and upper seat rows) originally rested on fourteen walls in opus reticulatum (one of which is missing as a result of the heavy spoliation mentioned above), which in turn defined a series of vaulted rooms. Apart from its location, the central room stands out for the presence of plaster on its walls: the excavation revealed the existence of a floor in (roof-)tiles, covered by a thin layer of mortar (only partially preserved), its northern end closed by a very badly preserved wall made up of stones apparently bonded with mortar. At the moment it is not possible to hypothesise about the function of this room.

The core building was surrounded on three sides by a broad perimeter corridor [J] (ca. 5 m wide), bringing the overall size of the building to 55 m × 31 m. This passageway was accessible from the outside through a series of large doorways (as attested by the square pivot sockets on the surviving threshold slabs): it probably functioned as an elegant reception space for spectators (the walls were decorated with elaborate frescoes), whereas its long side likely doubled as a postscaenium (backstage) once the audience had taken their seats. A trench [N] opened just behind the valvae regiae (the main central onstage doorway) has so far provided evidence for both earlier and later occupation: a) remains of two parallel walls in opus quadratum (local travertine) dated to the 3rd–2nd c. BC and cut by the (later) foundations of the theatre, and b) traces of iron-melting activities (apparently the ‘recycling’ of nails as part of the spoliation process).

Outside the building, abundant remains of a stone gutter [O] have been found placed along the external walls of the perimeter corridor: a circular hole on its western corner (13 cm in diameter) allowed the gutter to discharge the rainwater into a covered drain (37 cm wide). Last but not least, immediately outside the access to the western stairway mentioned above, a spoliation layer yielded a remarkably intact stone sundial, inscribed with the name (Marcus Novius Tubula) and the office (Plebeian Tribune) of the person who paid for it: the object – still under study – was clearly not in situ and might have been originally placed somewhere within the nearby forum (less than 50 m away from the find-spot).

The 2017 excavation has further confirmed the chronology of the theatre: its first phase dates to the second half of the 1st c. BC, whereas the refurbishing of the scaenae frons belongs to a second phase in the course of the 1st c. AD. The theatre's auditorium (cavea, prohedria and tribunalia) could have seated an estimated 1,500 spectators.

Acknowledgements

This project is a partnership between the Faculty of Classics of the University of Cambridge, the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per le Province di Frosinone, Latina e Rieti and the British School at Rome, in further collaboration with the Department of Archaeology of Ghent University (GPR survey). The 2017 season was made possible by the generous support of the Isaac Newton Trust [INT 16.38(o)], the Arts and Humanities Research Council [AH/M006522/1], the Faculty of Classics of the University of Cambridge, the Comune di Pignataro Interamna and Mr Antonino Silvestro Evangelista.