INTRODUCTION

The Observant Franciscan friar (Minore Osservante) Padre Carlo Lodoli (1690–1761) (Fig. 1)Footnote 1 was a major Venetian cultural figure in close touch with many contemporary artists, literati and influential members of the patrician élite, and probably the most avant-garde architectural theorist of the Enlightenment. His theory is worthy of study and significant for eighteenth-century architecture and for the broader history of architecture because he represents a link between Renaissance architectural theory and modern design, one that is rooted in his own time. Championing a rational and a functional new architecture, to which he gave the name of ‘arte nuova’ or ‘nuovo instituto’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 25, 33; II, 50), his tabula rasa ideas on architecture have been viewed in Italian Modern Movement historiography and by Emil Kaufmann (1891–1953) as precursors of modernist principles.Footnote 2 Lodoli's main contribution to the architectural debate of the eighteenth century was to base architectural design on Galileo Galilei's discovery of the new science of strength of materials, as formulated in his Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche intorno a due nuove scienze (‘Discourses and mathematical demonstrations concerning two new sciences’), published in Leiden in 1638.Footnote 3 Scientific solidity is for Lodoli the first and essential goal of architecture, which should grow out of the nature of the materials used (‘indole della materia’) and from Galilean mechanical principles. He seems to have been the first to think that architecture could be judged by the ethical concept of truthfulness or honesty and to apply this concept to wood and stone.Footnote 4 In this way, he was a forerunner of Augustus W.N. Pugin (1812–1852), John Ruskin (1819–1900), Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) and Gottfried Semper (1803–1879).

Fig. 1. Alessandro Longhi, Portrait of Carlo Lodoli, c. 1755, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, inv. no. 908 (photo by courtesy of the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice).

Lodoli is credited with anticipating the modernist motto ‘form follows function’,Footnote 5 although for him the concept of function was not synonymous with use, but more directly related to truth and the use of materials in building according to their own specific properties. Statics and the search for an architecture true to materials and to methods of construction are actually at the centre of Lodoli's doctrine.Footnote 6 He was indeed the first architectural theorist to formulate the doctrine of truth-to-material and to introduce the notion of function into architectural discourse, as stated in his distichon Footnote 7 DEVONSI UNIR E FABRICA E RAGIONE / E SIA FUNZION LA RAPPRESENTAZIONE (‘Building must be united with reason, and let function be the representation’).Footnote 8 It appeared on an oval stone frame surrounding his portrait by the Venetian painter Alessandro Longhi (1733–1813), now apparently lost, but known from a widely circulated print engraved by Pietro Marco Vitali (1755–1810) (Fig. 2). It serves as the frontispiece to the first volume of Memmo's Elementi dell'architettura Lodoliana, published in Rome in 1786.

Fig. 2. Pietro M. Vitali, Portrait of Carlo Lodoli, engraving after the portrait by Alessandro Longhi, Museo Correr, Venice, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, inv. L. V. 1164 (photo: 2018 © Archivio Fotografico — Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia).

The second half of the portrait motto — E SIA FUNZION LA RAPRESENTAZIONE — is the versified form of Lodoli's famous maxim and his most important architectural principle, which reads according to Algarotti: ‘Niuna cosa, egli insiste [Lodoli], metter si dee in rappresentazione, che non sia anche veramente in funzione’ (Algarotti, Reference Algarotti1764: II, 62–3). It appears to be Lodoli's own Italian translation of the following sentence from Vitruvius’ De Architectura (4.2.5): ita quod non potest in veritate fieri, id non putaverunt in imaginibus factum posse certam rationem habere. This is confirmed by Memmo when he writes:

Padre Lodoli far from being a declared enemy of every ornament as the Count [Algarotti] made him out to be, did not dream of excluding it entirely, provided it was not placed where it was contrary to decorum; as to which Vitruvius reasons well, namely that one must never put in an image, or in Lodoli's more precise term [‘in rappresentazione’], that which never could have existed in truth, or as he said, in function. (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 38, my emphasis)

The words in veritate in Vitruvius’ maxim and in Lodoli's translation as ‘in funzione’ are therefore directly connected to the concept of truth or veritas in architecture. The words ‘in rappresentazione’ by Lodoli appear, in turn, to be the Italian translation of in imaginibus (imago being a picture, image, graphic depiction, design or representation) in Vitruvius’ maxim. The concept of representation had already been used by Daniele Barbaro (1508–1570) in his 1556 Italian edition of Vitruvius in the statement: ‘many architects have given little consideration to what Vitruvius says, that is that we should not do anything which does not seem plausible, nor represent [rappresentare] any image that does not have a basis in truth, & that, coming under discussion, cannot turn to a secure place for support’ (Barbaro, [1556] Reference Barbaro1567: 171, my emphasis).Footnote 9 Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) uses the term ‘in figura’ for in imaginibus in his Italian quotation of the relevant Vitruvian sentence in his Della magnificenza ed architettura de’ romani (Piranesi, Reference Piranesi1761: ch. LX, xcvii; ch. LXV, cvii).

In order to establish a history of modernism, Edgar Kaufmann (Reference Kaufmann1964) translated ‘funzione e rappresentazione’ as ‘function and form’, clearly intending an allusion to the famous motto ‘form follows function’ which was used for the first time by Louis Sullivan in 1896 (Poerschke, Reference Poerschke2016: 29). ‘Form’, however, refers more specifically to the visible shape or configuration of an architectural object, instead of its mere graphic depiction or design, as suggested by Vitruvius, Barbaro, Memmo and Piranesi. For Lodoli, ‘solidity (“solidità”), analogy (“analogia” [the Greek Vitruvian term for proportion which Lodoli defines as the proportional regular correspondence between parts and the whole in Book II of his treatise]) and comfort (“comodo”) are the essential properties of representation’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 59). Another statement defines representation as ‘the individual and total expression that results from the material when it is employed according to geometric–arithmetic–optical [that is, mathematical] reasons for a proposed end’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 60).

Characterized by his contemporaries as a ‘new Diogenes’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 39) because of his provocative and cynical social behaviour,Footnote 10 and ‘the Socrates of architecture’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, ‘Al lettore’ (not numbered)),Footnote 11 partly for his quizzical method of teaching and teasing his contemporaries, and partly for his refusal to commit himself to print, Lodoli seems, however, to have written extensively on various subjects, including philosophy and architecture. Memmo reported that Lodoli ‘said he did not want to print his treatise on architecture’. Recently published documents give, for the first time, the original title of Lodoli's architectural treatise as Nuove riflessioni sopra la meccanica costruzione del solido ed ornamento in tutti li monumenti dell'architettura (‘New thoughts on the statics of firmness and ornament in all architectural monuments’) (Cellauro, [2013] Reference Cellauro2015: 244–9). It was circulated in parts from 1736 among the Venetian cultural elite and completed in 1754.

Lodoli's ideas on architecture are only known indirectly, from the writings of Zaccaria Sceriman (1708–1784) in his philosophical novel Viaggi di Enrico Wanton alle terre incognite australi ed ai regni delle Scimmie e dei Cinocefali (‘The travels of Henry Wanton to the unexplored southern lands and the kingdoms of the apes and of the dog-faced people’) (Venice, Reference Sceriman1749); from Count Francesco Algarotti (1712–1764), one of Lodoli's earliest pupils in c. 1725–30, in his Saggio sopra l'architettura (Pisa, 1756) (Algarotti, Reference Algarotti1764); and from the Venetian patrician Andrea Memmo (1729–1793) in his Elementi dell'architettura Lodoliana, ossia l'arte del fabbricare con solidità scientifica e con eleganza non capricciosa (‘Elements of Lodolian architecture, or the art of building with scientific firmness and uncapricious elegance’) (Rome, 1786; and Zara, Reference Memmo1833–4).

This paper is intended to throw light on Lodoli's concept of ‘architettura organica’, an important facet of his design theory. He applied this novel concept to the aspect of architecture related to the design of ‘all sorts of furnishings’. This expression appears only once in Memmo's treatise, when he is discussing Lodoli's interest in furniture and furnishing design. But he states explicitly that it was perhaps Lodoli who coined the expression when he writes ‘which he, perhaps using an expression that he had invented, used to call organic architecture’.Footnote 12 Indeed, several historians and architects, such as Alberto Sartoris (Reference Sartoris1954: 191; Reference Sartoris, Grassi and Pepe1978), Luigi Grassi and Mario Pepe, and Joseph Rykwert ([1992] Reference Rykwert2007; [1976] Reference Rykwert2008), have pointed out that the first use of the term ‘organic’ in architecture can be traced back to the middle of the eighteenth century when Lodoli introduced it as a new design concept. Although a good deal has been published about him since his rediscovery in the 1930s, this aspect of his design theory has not been fully explained. Rykwert ([1992] Reference Rykwert2007; [1976] Reference Rykwert2008) and Clelia Alberici (Reference Alberici1980: 190) have briefly discussed Lodoli's interest in organic architecture. Thus, Rykwert ([1976] Reference Rykwert2008: 372) characterized Lodoli as the theorist who ‘liked the term function … and coined the expression organic architecture’, and as ‘the first to have spoken of an “organic architecture”, even if he applied the term only to furnishings’ ([1992] Reference Rykwert2007: 342). This paper, besides discussing Lodoli's theory of organic architecture in more detail, is also intended to support the idea that Lodoli extended his concept to architecture proper. It stresses the importance of the notion of comfort in Lodoli's theory of organic architecture both in furniture design and in architecture, while placing it in the context of a widely shared new concern for comfort among French architects and furniture makers of the Enlightenment.

LODOLI'S CONCEPT OF ORGANIC ARCHITECTURE

Organic architecture is today considered as an early twentieth-century avant-garde philosophy of design, although the expression had its roots in the mid-eighteenth century and had a legacy in the nineteenth.Footnote 13 As a philosopher of the Age of the Enlightenment, Lodoli gave a different meaning to the expression ‘organic architecture’ from what is widely understood today by relating it primarily to a quest for comfort. He introduced the expression to draw the attention of his contemporaries to the urgent problem of inventing a new way of designing furniture and buildings to fit the purpose of comodità or comfort (Lodoli also used the adjective comodo).Footnote 14 Far from its modern usage, Lodoli's organic architecture was based on taking into consideration the anatomic shape and the anthropometrics of the human body in order to achieve comfort (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 84). As such, Lodoli's organica may be regarded as an eighteenth-century equivalent to the modern field of Human Factors and Ergonomics (HF&E) in its goals of a human-centred design and its search for comfort and well-being.Footnote 15 His organic architecture may thus be regarded as pre-empting by 200 years physical ergonomics, a specialization within the general field of HF&E which is concerned with human anatomy, and some of the anthropometric, physiological and biomechanical characteristics as they relate to physical activity. While there is compelling evidence that the ancient Greeks had adopted a human-centred design approach, trying to fit architecture, tools and workplaces to the human body (Marmaras, Poulakakis and Papakostopoulos, Reference Marmaras, Poulakakis and Papakostopoulos1999), modern ergonomic design principles, in content if not in name, seem to have re-emerged in the early modern period in Lodoli's ideals and those of his contemporaries.

The first decade of the nineteenth century witnessed the first use of the term ‘organic’ in explicit connection with architecture proper, rather than with furnishings as in Lodoli's design theory. It was then referred to the harmonious relationship of the parts to the whole of a building, based on visible, measurable units and modules (anthropometric proportion). Ute Poerschke (Reference Poerschke2016: 73) and Georg Germann (Reference Germann1972: 36) note that this conception can be traced in early sources, such as Filarete (c. 1400–1469), who wrote around 1460: ‘As man wishes his body to be well disposed and organized [bene orghanezzato] … so it is with the building.’ Germann also describes how the natural scientist Charles Bonnet in Geneva defined the ‘organic whole’ in 1762 in his studies of genetics, noting that Aloys Hirt (1759–1837) was the first to transfer this term to architecture in his Die Baukunst nach den Grundsätzen des Alten of 1809 (Germann, Reference Germann1972: 36):

Every architectural work can be regarded as an organic whole [organisches Ganzes] that consists of main, subordinate, and auxiliary parts in a certain proportion to one another … For example, if one wishes to determine the proportions of the parts to the whole, one takes any part of this body as the measure, such as the elbow, the foot, the instep, the breadth of a hand, the width of a finger, the length of the head or face. One proceeds in a similar way with buildings, making some part of the building to be realized the measure by which all the others are determined. Usually, one takes the measure of the bottom of a column for the purpose or half of that.Footnote 16

All elements of this definition of the organic can already be found in Vitruvius’ De Architectura Libri Decem. Vitruvius initially describes anthropomorphism with the example of Dinocrates and with a study of the Doric column (De Arch., 2. praef. 2; 4.1.6).Footnote 17 However, the most comprehensive as well as the most prominent remarks on human measurement as architectural measurement are found at the beginning of his third book. There he writes that the design of a religious building is based on symmetria and analogia and that this design corresponds to the right organization of the human body. For Vitruvius, analogia was generated from the module and gave rise to symmetria, or commensurability of the parts. As nature produced symmetria in a well-shaped human body, so the architect set out to do the same thing in designing a temple.

New conceptions of the organic emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, particularly in America. Its modern usage in the United States seems to stem from the American sculptor and architectural theorist Horatio Greenough (1805–1852), but its more particular use as a description of architecture sympathetic to its environment comes from the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1957) and the Prairie School. In an 1843 essay, ‘American Architecture’, Greenough advocated that American architects should create an original organic architecture. He emphasized the importance of focusing on the practical instead of the aesthetic aspects of nature, stressing the variety as well as the method of organic solutions for specific structural problems in architecture. He suggested that form should follow function, and that two identical structures should not exist as each must have its own individuality.Footnote 18

The modern notion of the ‘organic’ in architecture was, however, not formally articulated until Louis H. Sullivan's Kindergarten Chats of 1901. This includes the following:

in seeking now a reasonably solid grasp of the value of the word organic, we should at the beginning fix in mind the values of the correlated words, organism, structure, function, growth, development, form. All these words imply the initiating pressure of a living force and a resultant structure or mechanism whereby such force is made manifest and operative … (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan1947: 48)Footnote 19

Also, ‘if the work is to be organic the function of the parts must have the same quality as the function of the whole’ (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan1947: 47), echoing the conception already expressed by Aloys Hirt of the harmonious relationship of the parts to the whole. Such statements prove that the idea of the ‘organic’ adopted by Sullivan was based upon an analogy between the processes of nature and those of human creation.

Organic architecture is today best known as a term used by Frank Lloyd Wright to describe his approach to architectural design in his book An Organic Architecture: The Architecture of Democracy (Reference Wright1939). He had first used the term in a manifesto entitled ‘In the Cause of Architecture’, published in March 1908 in the professional journal Architectural Record, where organic architecture is defined by the statement that: ‘A building should appear to grow easily from its site and be shaped to harmonize with its surroundings’ (Wright, Reference Wright1953: 55). For Wright, organic architecture is a philosophy of architecture, which promotes a harmonious relationship between a building and its environment through design approaches so sympathetic and well integrated with their sites that buildings, furnishings and surroundings become part of a unified, interrelated composition.Footnote 20

A possible link between Lodoli and the avant-garde architects of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries may be illustrated by the introduction of the notion of the ‘organic’ in Greenough's theoretical writings. These seem to be more alike to Lodoli's ideas than to those of Sullivan or Wright, as Greenough may have borrowed from Memmo the terms ‘organic’ and ‘function’. There may be a connection between Lodoli and Greenough, but this has not yet been firmly established. Greenough knew Italian and from 1829 spent fifteen years in Florence (Ciregna, Reference Ciregna and Salenius2009), where he may have come across a copy of Memmo's treatise after the publication in 1833–4 of the second edition.Footnote 21 He could, however, have also borrowed the term ‘function’ from Algarotti's treatise or from Francesco Milizia's many writings (Rykwert, [1976] Reference Rykwert2008: 22). The latter took from Algarotti's Saggio sopra l'ar chitettura entire sections and, almost word for word, his sentences on function and representation, and did so in five different treatises.Footnote 22

ETYMOLOGY OF LODOLI'S ORGANICA

The etymology of the word organica in Lodoli's expression should be discussed in the context of contemporary definitions of the term, particularly in Italian dictionaries of the time. The fourth edition of the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca, published in Florence in 1729–38 (but originally published in 1612), defines the word ‘organico’ as stemming from the word ‘organo, e.g. strumentale’, ‘from organ, e.g. instrumental’, and the word ‘organo’ as a ‘strumento per mezzo del quale l'animale fa le sue operazioni’, or as the ‘instrument by which the animal performs its operations’.Footnote 23 The source for the Italian word ‘organo’ is the Greek ὄργανον (organon), which comes from the same root as ἐργον (ergon) ‘work’, and which had the linked meaning of ‘implement, instrument, tool’, that is, something one works with. It is the name given by Aristotle to his treatise on logic (in the sense of the instrument of all reasoning). The word was used in its Latin form by Francis Bacon in 1620 as the title of his philosophical treatise Novum Organum (New instrument), which laid out a new set of principles for scientific investigation. Aristotle (De Partibus Animalium, 687a) had also used the term to signify every bodily member as an instrument, and especially the hand, because it is the most particularly human faculty (Rykwert, [1992] Reference Rykwert2007: 341). The commonest unqualified use of the word ‘organ’ for any part of the body was to signify the mouth and tongue, the instruments of the human voice, from which the term was transferred to several other parts until it was used for most of the internal organs, both human and animal. But because it was also used as a synonym for ‘agent’, in the eighteenth century it came to be used as a metaphor for the whole body (and the human body in particular) (Rykwert, [1992] Reference Rykwert2007: 341–2). From its Aristotelian application to any of the specialized functional parts of living things, our word ‘organism’Footnote 24 was coined for the whole body, seen as an assemblage of organs (a closely related word is ‘organization’, originally ‘the condition of being ordered as a living being’, or ‘to organize’ (‘organizzare’ in Italian), which the Vocabolario della Crusca defines as ‘formare gli organi del corpo dell'animale’ (‘to form the organs of the animal’). In the eighteenth century, this led to the adjective ‘organic’, ‘of or pertaining to the bodily organs’. Later in the century, this evolved to mean anything that had organs, hence any living thing, and began to be contrasted with ‘inorganic’.

To Lodoli, the word ‘organic’ seems to have referred primarily to the human body and its organs, and thus, primarily, had an anatomical connotation. In the other two occurrences of the word found in the Vocabolario della Crusca (1729–38), it is particularly used to characterize parts of the human body related to the five senses: ‘Nose: a noted part of the face, organ of smell’ (s.v. ‘Naso’); ‘Hearing: one of the five senses [sentimenti], of which the organ is the ear’ (s.v. ‘Udito’). This demonstrates that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the word organo was also understood (besides its other meaning of instrument) as relating to the specific organs by which the five senses are experienced: the mouth and tongue, the hands, the eye, the nose, and the ears. As a result, it is possible that the expression ‘organic architecture’ may have stemmed from this current usage of the word. It may therefore have had for Lodoli and his contemporaries a strong connotation with the senses, besides its anatomical meaning. Indeed, levels of well-being and comfort may be assessed according to the degree of satisfaction of the senses, and the many positive or negative sensations emanating from them are an important factor in this assessment. The Vocabolario della Crusca (1729–38) defines thus comodo as ‘everything which is quiet and of satisfaction of the senses … Latin Commodum, Commoditas’.Footnote 25 It is possible that Lodoli had known the Traité des sensations, published in Paris in 1754, by the French philosopher and epistemologist Etienne Bonnot de Condillac (1715–1780), when formulating his concept of organic architecture, although this is only speculation, as the catalogue of Lodoli's library and collections of drawings and prints at his quarters in the monastery of San Francesco della Vigna is lost.Footnote 26 It is important to stress, however, that the word ‘organic’ was not mentioned in this essay — though ‘organ’ in the singular and plural did occur repeatedly in connection with the senses and the sensations. Condillac's influential treatise had a significant impact on contemporary architectural and landscape design theory, as for example in the approach displayed by Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières (1721–1789), in his treatise Le Génie de l'Architecture, ou L'analogie de cet art avec nos sensations (Paris, 1780).Footnote 27

LODOLI'S ORGANIC CHAIR

Lodoli's organic theories were put into practice in his design of an anatomic armchair of which both the back and the seat were concave. Sometime after Lodoli's invention, writes Memmo ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 84), a not dissimilar chair was brought back from Paris to Venice by ‘my good friend, the Baily [or Venetian ambassador to Constantinopole] Tommaso Giuseppe Farsetti [1720–1791], Patrician of Venice’Footnote 28 (Farsetti moved in the Lodoli circle, as his cousin Filippo (1703–1774), the famous art collector and Canova's first patron, had been one of Lodoli's earliest pupils).Footnote 29 The shoulders, Lodoli maintained, dictated the form of the back of his ‘organic’ chair, and the bottom, that of the seat, thus revolutionizing the art of the Venetian baroque and rococo armchair. Prior to the mid-eighteenth century, the chair functioned first and foremost as a status symbol. All chairs were essentially substitutes for the Venetian patrician seat, the seggiolone (in Memmo's word; see below) or throne. In every dwelling, the best chair was reserved for the head of the house; this was particularly true of any chair with arms. Early armchairs featured an overwhelmingly tall, wide, straight back and were clearly meant to be imposing rather than comfortable, a sort of informal throne and the ideal seat for the age of magnificence. A good example of such design is represented by the throne designed by the Venetian rococo sculptor Antonio Corradini (1688–1752), now preserved at the Museo del Settecento Veneziano at Ca’ Rezzonico (Fig. 3). Designed in the first decades of the eighteenth century, it is in gilded wood, lavishly decorated with putti, nereids and marine horses. It was used by Pope Pius VII on 10 March 1782 when he visited Chioggia as a guest of the Grassi family.

Fig. 3. Antonio Corradini, Throne Chair, c. 1720–40, Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca’ Rezzonico, inv. Cl. XXII, without number (photo: 2018 © Archivio Fotografico – Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia).

So far, Lodoli's organic chair has not been traced, although a unique eighteenth-century Venetian wooden armchair with four oblique, straight legs, sold in 2010 in Parma at the Mercante in Fiera,Footnote 30 presents the unusual characteristics of being concave on the backrest and on the seat, and thus may conceivably have been designed by Lodoli himself (Figs 4–5). This chair, bought in Venice at the beginning of the twentieth century by an Italian ambassador, re-emerged when the heirs of the ambassador's daughter decided to sell it. It has been acquired by a private collector as an item that, apparently, originally belonged to the ducal collection of furniture.Footnote 31 The decoration is reduced to a minimum: a small gilded ornamental fleuron (or palmette-like) finial at the top on the backrest (perhaps based on the idea of an acroterion), and a small wooden sphere at each end of the armrests, the hollows of which recall the holes in a Chinese ball. The function of these spheres seems to be to permit the seated user to hold them for better stability of the lower arms. This organic chair may be tentatively dated to c. 1755–60 when Lodoli's architectural maturity and design theory reached their peak and after the completion of the manuscript of his treatise on architecture in 1754.Footnote 32 In addition, such a dating conforms with the fact that there is no mention of Lodoli's interest in organic architecture and in furniture design in Algarotti's Saggio sopra l'architettura of 1756.

Fig. 4. Carlo Lodoli?, Mid-Eighteenth-Century Venetian Armchair, private collection of Marco Sgarbi, Villa Poma, Mantua (photo: Marco Sgarbi).

Fig. 5. Carlo Lodoli?, Mid-Eighteenth-Century Venetian Armchair, private collection of Marco Sgargi, Villa Poma, Mantua (photo: Marco Sgarbi).

Memmo ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 84) states that Lodoli's armchair was partially based on ‘an ancient Roman chair’, alluding most probably to a klismos (Fig. 6). The klismos or light chair is believed to have been an original Greek discovery dating back to the mid-fifth century BC. It had four curving, splayed legs and curved back rails with a narrow concave backrest. Though none has survived, such chairs often appear on ancient reliefs and paintings, and on Greek red-figure or black-figure vases (Fig. 7) (Richter, Reference Richter1966: 33–7 and illustrations 106–97). To judge from these representations, it is the comfortable chair par excellence, less formal than the throne, more luxurious than the diphros. Gisela M.A. Richter (Reference Richter1966: 34) characterized the klismos as ‘one of the most graceful creations in furniture, combining comfort with simplicity and elegance’. According to Homer, it was the seat of the gods, but many pictorial representations survive showing that it was also the seat used by women at their toilet or youths taking music lessons (Richter, Reference Richter1966: illustrations 171, 184). A vase painting of a satyr carrying a klismos on his shoulder suggests that it was very light (Richter, Reference Richter1966: illustrations 180–1).

Fig. 6. Reconstructed Klismos Chair, c. 1920, after Louis-François Battenfeld and Emmanuel Pontremoli, Villa Kerylos, Beaulieu-sur-Mer, France (photo: Pascal Lemaȋtre/Centre des Monuments Nationaux, Paris).

Fig. 7. Bearded Man seated on a Klismos Chair, from the Tombstone Relief of Xanthippos, Stela, Attic, Athens, c. 420, Monastery of Petraki, Monastery of Asomato, British Museum no. 1805,0703.183 (photo: Trustees of the British Museum, London).

Lodoli's armchair was, however, rather different from the klismos type, as it not only had a concave backrest like the Greek or the modern French models, but ‘was curved in the part where you sit, as later became customary in England’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 84). The chair discussed in this paper as perhaps designed by Lodoli shows these unusual characteristics, which illustrate perfectly Lodoli's concept of organic architecture rather than a generic neoclassical attitude. In fact, Lodoli had merely taken the classical klismos type as a point of departure for the design of an entirely new modern chair. His original intention was to improve its design through a greater adjustment to human anatomy for perfect comfort.

Forms like the klismos, modelled on ancient furniture prototypes, became popular for the first time only in the second, archaeological phase of neoclassicism in the 1780s, although for decades artists and designers had had access to information about such antiquities. For instance, in 1760, shortly before Lodoli's death, Le antichità di Ercolano (1760: II, 53) had illustrated two images from Roman wall paintings of women seated in klismos chairs of exaggerated form. Shortly afterwards, in 1767, the Comte de Caylus's Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises (Paris, 1752–67, 7 vols) published a more recognizable klismos, as depicted on a carved relief (see de Lévis de Tubières-Grimoard, Reference de Lévis de Tubières-Grimoard and Comte de Caylus1967: VII, pl. 38). It is thus likely that, before these first publications illustrating klismoi were published, Lodoli had access to their representations in figurative archaeological material, which circulated in the Veneto among patrons, scholars and artists.

Modern klismos chairs were first widely seen in Paris in the furniture made by Georges Jacob (1739–1814) in 1788 for Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), to be used as props in David's historical paintings where the new sense of historicism required visual authenticity (Watson, Reference Watson1960: 75–6). It would be hard to find a French klismos chair earlier than the ones designed by the architect Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1751–1821) in 1786, for a decor in the ‘Etruscan style’ for the Hôtel Montholon, boulevard Montmartre, and executed by Jacob. In London, early klismos chairs were designed by Thomas Hope (1769–1831) for his house in Duchess Street, London.

The design of Lodoli's organic chair was certainly influenced by the change which had occurred in France in furniture design from the end of the seventeenth century onwards. Joan DeJean (Reference DeJean2009) has shown that the earliest indications of the quest for comfort appear in France as early as the 1670s; they all featured the same two words, which began to be used in a new way and to be given prominence. The adjective commode and the noun commodité originally implied convenience and were used in the Renaissance as synonyms for the Vitruvian utilitas. DeJean has shown that

from the 1670s these words were increasingly used in the domestic realm, to designate all that produced a sense of well-being and ease. As soon as new models of architecture, furniture, and dress gained prominence, commode and commodité came to signify well-being in one's surroundings. Homes, garments, chairs, and carriages all began to be valued for their commodité. (DeJean, Reference DeJean2009: 6)

Furniture was associated with architecture in becoming modern. New pieces and styles of furniture were used in newly invented rooms. Between 1675 and 1740, people went from living only with a few stiff chairs with no padding to living surrounded by an array of well-stuffed and padded, curvy and ‘orthopedically’ proportioned seats ranging from armchairs, sofas and fauteuils de commodité to daybeds, canapés and chaises longues. And these new seats — the first furniture ever designed with comfort in mind — became present in all interior rooms (DeJean, Reference DeJean2009: 102–30).

In about 1740, curvature finally was applied to the back of the armchair with the invention of what the carpenter and cabinetmaker André Jacob Roubo (1739–1791) calls, in the introduction to his L'Art du menuisier published in 1769, ‘the most fashionable chair of the day’, the cabriolet (Fig. 8). Prior to this, the backs of armchairs had been inclined and were curved along the top and sides, but they had remained flat. With the appearance of the cabriolet, all flat-backed styles became known as à la reine. Rounded, curving armchairs soon became known as French chairs; craftsmen elsewhere copied the style, but everyone agreed that the best such chairs were those that had been made in France. The cabriolet with the comfortable circularity of its ‘fit against the back’ was therefore an important precedent for Lodoli's organic chair. Its main difference lay in the fact that it was concave on both the back and the seat, a variation on both the classical theme of the klismos and the modern cabriolet.

Fig. 8. Plans, Cross-Section, and Elevations of a Cabriolet Chair, from André Jacob Roubo, L'Art du menuisier (Paris: De l'imprimerie de L.F. Delatour, 1769, vol. I). The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (85-B4434) (photo: The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles).

‘HOUSES LIKE CHAIRS DESIGNED WITH REASON’: LODOLI'S ORGANIC CHAIR AS A PARADIGM OF A NEW ARCHITECTURE

Lodoli seems to have extended his concept of organic architecture to buildings and to architecture proper, since Memmo ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 85) reports that he would have liked architects to design ‘houses like chairs designed with reason’. This statement was reportedly made by Lodoli when he exhibited his organic chair along with a traditional Venetian throne chair (‘seggiolone’) as a comparative pair, to demonstrate the superiority of his approach over traditional furniture design and classical architecture. On that occasion, the bulky and uncomfortable ‘seggiolone’ became the metaphor for a major Renaissance palace, the Palazzo Grimani at San Luca in Venice (Fig. 9), and, more generally, for all classical architecture (ancient and modern), and the organic chair which Lodoli had invented, the paradigm of his new organic architecture. In his guide to Venice in 1581, Francesco Sansovino had declared that four patrician palaces in the city surpassed all the others in size, grandeur, expense and Vitruvian discipline. These were his father's two palaces for the Dolfin and Corner families, the Palazzo Grimani at San Luca, and Mauro Codussi's Palazzo Loredan, all of which, he claimed, had cost more than 200,000 ducats. Much admired in the eighteenth century, the Palazzo Grimani was given no fewer than nine illustrations by Antonio Visentini (1688–1782) in his series of drawings Admiranda Urbis Venetae (1730–40), with captions by the British consul, Joseph Smith (1682–1770).Footnote 33 Gerolamo Grimani, procurator of San Marco and father of Doge Marino, was the initiator of the palace, which was finally begun in 1556 according to a design by the Veronese architect Michele Sanmicheli (1484–1559). After Sanmicheli's death in 1559, it was completed by Gian Giacomo de’ Grigi from Bergamo. Sanmicheli's palace is far smaller than it appears, because the site rapidly narrows towards the rear. The Corinthian orders paired on each side of the outer bays on the three storeys and the triumphal arch rhythm of the central bays give it a distinctly Roman air and create a sense of magnificence. As usual in Venetian palaces, the plan is tripartite, with a long central androne, and because of the restrictions of the site the courtyard is at the very back (Fig. 10).Footnote 34 It contained relatively few rooms, which are roughly square or rectangular; all of them are interconnected, and all space was public or virtually so. According to Memmo, Lodoli's criticism of both the traditional ‘seggiolone’ and the Palazzo Grimani was related to their overt lack of comfort. Memmo writes,

One day he [Lodoli] placed the chair he had invented next to one of those imposing throne chairs lined in Russian leather (‘bulgaro’), square-shaped, heavy, laden with metal studs (‘bollettoni’) and ornate carvings, positioned precisely in the armrests so that it was impossible to rest one's elbows without feeling discomfort, and when attempting to sit, it was necessary to hurl one's body and then slide down, due to the disadvantage of the chair's height, and the rather tall, upright and hard backrest of the seat. On that occasion, he said to a Venetian patrician who owned one of the most renowned palatial buildings in Venice, namely, Mr Girolamo Grimani from San Luca, while pointing to the chair: ‘Here you are in your magnificent palace, costly and expensive, but not appropriate for your use. The Sanmichelis and the Palladios, in imitation of the ancients, like those who made these bulky chairs without ever considering the simple requirements of bare reason, forced everyone to feel uncomfortable. And could we not design houses like chairs designed with reason? Also carved, varnished, gilded as much as desired in order to satisfy one's need for luxury, but without neglecting comfort [“comodo”],’ he said, ‘and with the appropriate strength and stability. Sit on one chair and sit on the other, and you will experience yourself whether it is more comfortable to follow the dictates of the ancients or ignore them to give reason the upper hand.’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 84–5)

Fig. 9. Michele Sanmicheli, Palazzo Grimani, San Luca, Venice, facade (photo: author).

Fig. 10. Palazzo Grimani, San Luca, Ground-plan, from L. Cicognara, A. Diedo and G.A. Selva, Le fabbriche e i monumenti cospicui di Venezia, (Venice: Nello stabilimento nazionale di G. Antonelli, 1858). The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (83-B2298) (photo: The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles).

It is not exactly known what Lodoli found uncomfortable in the Palazzo Grimani. His criticism of the ‘seggiolone’ reveals, however, that he may have rejected its imposing square-shaped exterior structure and box-like rooms, its lavish classical orders, its overwhelming high ceilings and its oversized rooms. It is worth remembering that, according to Lodoli, the paradigm of a rational, functional architecture is to be found in the design of the Venetian gondola (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 86–7). Perhaps its oddest characteristic is that it is not only asymmetrical in plan, but in section as well, allowing the oarsmen to row on only one side, thus making the very large craft more easily manoeuvrable (Fig. 11). The curvy and asymmetrical shape of the gondola might perhaps have led Lodoli to favour an architecture that is far from being square-shaped and regular, and is in clear contrast to an orthogonal and symmetrical classical building like the Palazzo Grimani.

Fig. 11. Gilberto Penzo, Plan and Sections of an Eighteenth-Century Gondola (Reconstruction), private collection of Gilberto Penzo, Venice (photo: Gilberto Penzo).

Lodoli's statement about the Palazzo Grimani stresses the importance of the notion of comfort in his theory of organic architecture, and the role it played in its assessment of traditional material culture and modern architecture rooted in the imitation of the antique. This new emphasis on comfort resulted in Lodoli's transformation of the Vitruvian triad of firmitas, utilitas and venustas (‘firmness’ or ‘durability’, ‘utility’, and ‘delight’ or ‘beauty’)Footnote 35 into ‘solidità scientifica’ (‘scientific firmness’, attained by the application of the Galilean science of strength of materials), ‘analogia’ (‘anthropometric proportion’) and ‘comodità’ (‘ease’ or ‘comfort’) (Cellauro, Reference Cellauro2006: 44–6). The substitution of utilitas in Vitruvius’ triad with the alternative term of commoditas and its Italian equivalent ‘commodità’ had, however, already occurred during the Renaissance in Leon Battista Alberti's De Re Aedificatoria (completed in 1442),Footnote 36 and in its Cinquecento translations into Italian by Pietro Lauro (1546)Footnote 37 and Cosimo Bartoli (Reference Bartoli1550 and 1565), in Palladio's Quattro Libri (1570)Footnote 38 and in Sir Henry Wotton's Elements of Architecture (1624), which incorporated the English word ‘commodity’.Footnote 39 The Latin word derives of course from Vitruvius, though it had for the classical author a completely different meaning. In his definition of ordinatio (‘order’) (De Arch., 1.2.2), he uses the two words commoditas and modica as synonyms, both deriving from modus, the Latin word for ancient Greek μέτρον, metron (measure) (Lefas, Reference Lefas2000: 181). Commoditas is thus translated by Frank Granger as ‘balanced adjustment’,Footnote 40 and by Morris Hicky Morgan (Reference Morgan1914: 13) as that which ‘gives due measure’. During the Renaissance, the classical term was used as a synonym for the Vitruvian utilitas, or the Albertian usus, rather than as a synonym for ease. Palladio, for example, defines ‘commodità’ (translated by Tavernor and Schofield (Reference Tavernor and Schofield1997: 6) as ‘convenience’) in his Vitruvian triad, as being provided ‘when each member [‘membro’] is given its appropriate position, well situated, no less than dignity requires nor more than utility demands; each member will be correctly positioned when the loggias, halls, rooms, cellars, and granaries are located in the appropriate places’ (Tavernor and Schofield, Reference Tavernor and Schofield1997: 7).Footnote 41

It was in the Baroque age that the term evolved significantly towards the notion of ease, leading to a new attitude in domestic architecture. Patricia Waddy (Reference Waddy1990) has shown that comfort was a significant factor of planning in Roman baroque palaces. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the usual French term to assess satisfactory physical circumstance was ‘commodité’Footnote 42 (only in the early nineteenth century did ‘confort’ take on such French usage of the term commoditas, having borrowed the term back from the English language) (Rey, Reference Rey1985: s.v. ‘confort’; Pardaihlé-Galabrun, Reference Pardaihlé-Galabrun1988: 331; Auslander, Reference Auslander1996: 223). A similar meaning appears in the seventeenth-century Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca (s.v. ‘agio’) where the Italian word ‘commodità’ is mentioned as a synonym for ‘agio’ (‘ease’). This semantic evolution reached its peak in the eighteenth century. John E. Crowley (Reference Crowley1999) has shown that physical comfort — self-conscious satisfaction with the relationship between one's body and its immediate physical environment — was an innovative aspect of Enlightenment culture. Imaginative literature, political economy and humanitarian reform gave new attention to concerns about lighting, heating, ventilation, privacy, ease and hygiene in the design of the domestic environment. It is unlikely that any architect or designer before the last decades of the seventeenth century set out to design any type of dwelling with comfort among its architectural priorities (Crowley, Reference Crowley1999: 762–73; Reference Crowley2010). Indeed, between 1675 and 1740 there began a revolutionary transformation not only in the interior furnishings of residential buildings, but also in architecture, the period Joan DeJean (Reference DeJean2009) referred to as ‘the age of comfort’. The first formal sign of the way architecture was being redefined came in 1691 with the publication of Augustin Charles d'Aviler's Cours d'architecture, a treatise which Lodoli may well have known given his knowledge of French and his extensive reading, (he is indeed characterized by Memmo ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 70) as ‘a walking encyclopaedia’). For DeJean (Reference DeJean2009, 8) this treatise

marked the original appearance in print of the distinction that most clearly set French eighteenth-century architecture apart from what had preceded it: between ‘appartements de parade’, public space or reception rooms, and rooms to which architecture had never before paid attention, what d'Aviler called ‘appartements de commodité’ [comfort rooms], the interior rooms in which individuals actually lived, or in d'Aviler's words, ‘that which is less grand and more used’.

As soon as ‘commodité’ officially entered the vocabulary of architecture, two generations of French architects set about a revolution in domestic architecture. DeJean (Reference DeJean2009: 8) explains that

the most influential architects for the first time concentrated their energy no longer on the creation of imposing facades and on a building's exterior grandeur, no longer on showstopping reception space. They focused instead on interior architecture, rooms in which people could carry out their daily lives; private space gradually took over territory previously reserved for public space.

‘Comfort’ rooms proliferated, the size of rooms decreased and their number increased as rooms became more specialized. This resulted in the introduction of the original living rooms, and the very concept of private bedrooms and bathrooms, and the boudoir (DeJean, Reference DeJean2009: 144–85).

It is in this cultural context that Lodoli's great emphasis on comfort should be placed, resulting in a disposition to criticize both traditional material culture and classical architecture and in the glorification of reason. Algarotti maintained in his Saggio that Lodoli condemned all buildings, modern and ancient. Similarly, several of Lodoli's contemporaries disseminated the opinion that the Franciscan friar condemned in toto classical architecture and the study of antiquity. Lodoli's primary critique of ancient and modern architects was that they designed buildings/furniture by imitating antiquity rather than being led by reason, which would result in designs that would take into consideration (i) comfort, (ii) material properties and (iii) structural logic. Memmo mentions all three arguments, Algarotti only two — material properties and structural logic — as his treatise is only concerned with a critique of Lodoli's concept of truth in architecture.

THE REFURBISHMENT OF THE OSPIZIO DI TERRASANTA: AN EXAMPLE OF ORGANIC DESIGN

According to Memmo ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 152), Lodoli's only venture into practising architecture occurred when he assumed, from 1739 to 1751, the position of Commissario e Visitatore apostolico della Provincia di Creta and Padre Generale di Terra Santa (‘Commissioner for the Holy Land’), whereby he was in charge of pilgrims to the Holy Land passing through Venice under the care of the monastery of San Francesco della Vigna.Footnote 43 These pilgrims started and ended their journey at the monastery, but they also had to be housed, fed, transported and guided in Venice, at sea and in the Near East. For additional accommodation, Lodoli himself redesigned the Pilgrims’ Hospice (Ospizio di Terrasanta): a date inscribed on a stone tablet places the completion of this work in 1743 (Kaufmann, Reference Kaufmann and Searing1983; Caligaris, Reference Caligaris1990; Rykwert, [1976] Reference Rykwert2008). A small, dead-end courtyard preserves a part of the aspect of the Ospizio from Lodoli's time (Fig. 12). Here, with few resources, he put his architectural theories into practice, designing such features as doors and windows according to his own particular rules of function and representation.

Fig. 12. Courtyard, Ospizio di Terrasanta, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice (photo: Padre Rino Sgarbossa/Convent of San Francesco della Vigna, Venice].

The first part of the motto on Lodoli's portrait ‘DEVONSI UNIR E FABRICA E RAGIONE’ (in its Italian versified version in two lines) (Fig. 2) also appears on the foundation tablets of the Ospizio di Terrasanta. On one side is the date, 1743, and on the other, the portrait motto in its Latin Vitruvian version: EX FABRICA ET RATIO/CINATIO/NE. VITRUVIUS (Fig. 13). But Lodoli deliberately set the extra syllables /CINATIO/ within the O (in RATIONE) to play on the ambiguity between reasoning used by Vitruvius and reason as a general concept, so fundamental to the philosophy of the Enlightenment. The tablets are now in the dark passage which Memmo mentioned ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 153), and are barely visible. The phrase is derived from Vitruvius’ maxim ea (architectura) nascitur et fabrica et ratiocinatione, in paragraph 1.1.1:

The architect's expertise is enhanced by many disciplines and various sorts of specialized knowledge, all the works executed using these other skills are evaluated by his reasoned judgment. This expertise is born both of practice [fabrica] and of reasoning [ratiocinatio]. Practice is the constant, repeated exercise of the hands by which the work is brought to completion in whatever medium is required for the proposed design. Reasoning, however, is what can demonstrate and explain the proportion of completed works skilfully, and systematically. (Rowland and Howe, Reference Rowland and Howe1999: 21)

Fig. 13. Inscribed Stone Tablet, 1743, Ospizio di Terrasanta, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice (photo: Padre Rino Sgarbossa/Convent of San Francesco della Vigna, Venice).

The Vitruvian motto is repeated in the engraving of that singular, completely Lodolian door, which Giovanni Ziborghi with Giovanni Pasquali had published in 1748 in an edition of Vignola to which was appended an elementary book of instructions on mechanics dedicated to Lodoli (Vignola, Reference Vignola1748: II). As a frontispiece to the mechanics section, Ziborghi printed an engraving of a door of the Ospizio, with the same inscription within it: EX FABRICA ET RATIOCINATIONE. VITRUVIUS (Fig. 14). According to Memmo, Lodoli's translation of the maxim ran as follows: ‘Architecture is born no less from experience than from reasoning [“raziocinio”]’ (Memmo [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 174, my emphases), and he explained further that ‘Architecture is an intellectual and practical science, aimed at establishing through reasoning the good use and the proportions of artefacts and at understanding by experience the characteristics of materials which accompany them’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 275, my emphases). From this, it emerges that Lodoli interpreted the Vitruvian modus operandi of architectural production as essentially based on reason and on the experimental investigation of the various building materials. Reason and experience are key concepts of Enlightenment philosophy (Biasutti, Reference Biasutti and Biasutti1990a, Reference Biasutti1990b, Reference Biasutti, Barbarisi and Carnazzi2001), and it was with these concepts that Lodoli tried to give an up-to-date interpretation of Vitruvius’ definition of architecture in book I, chapter 1 of De Architectura, one that was to be consistent with the spirit of the age.

Fig. 14. Frontispiece, from Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, L'architettura di Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola ridotta a facile metodo per mezzo di osservazioni a profitto de’ studenti. Aggiuntovi un trattato di meccanica. Tomo primo[–secondo] (Venice: Giambattista Pasquali, 1748), vol. 2, Biblioteca civica Bertoliana G.26.1.2 (photo by courtesy of the Biblioteca civica Bertoliana, Vicenza).

The Ospizio had only six bedrooms for pilgrims, which gave on to each other so that pilgrims and porters (prior to redesign by Lodoli) had access only through each other's rooms. Lodoli wished to construct a new wide exterior gallery in stone to solve this problem but was unable to do so because of the expense involved. Observing that men are widest at the shoulders, he devised a new gallery in wood (now destroyed) with its flanks sloping outwards as they ascended, thus allowing pilgrims and monks, and particularly porters carrying pilgrims’ baggage on their shoulders, to pass one another abreast (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 154). In taking into account human anatomy, the design for the new wooden gallery can be considered as an example of Lodolian organic architecture applied to the design of a building proper, which resulted in an oblique wall, breaking with the orthogonality of classical architecture. Memmo reports that this ‘irregularity’ was criticized by many, although it provided ‘comodo’, or comfort (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 155). Lodoli also paid particular attention to visual comfort in providing appropriate natural lighting to the cells by opening doors and balconies onto the exterior wooden gallery. Memmo writes in this respect, ‘On this gallery he made doors opening into each room, and balconies opposite those existing in the wall of the room itself, so that the pilgrims, freed from the discomfort they suffered prior to the refurbishment, enjoyed sufficient lighting in each room’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 155).

The only surviving elements of the refurbishment are two windows with curious pediments (Fig. 15). Memmo discussed the thresholds first, calling them ‘an entirely new and entirely Lodolian invention’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 138); Fig. 16):

First, let us talk of sills. Everyone made them, and still makes them, in one piece so that the jambs bear on the ends thereof; jamb and sill weigh on the wall mass below. The portion of wall not compressed stays in place, creating a kind of fulcrum. This forces the sill upward, usually in the centre, as can be seen elsewhere. [Lodoli] divided the sill into three parts, the first as wide as the opening of the door or window, so that it bore no weight from the jambs. Shorter than usual and load-free, anyone can see that it would endure better. Nevertheless, he wanted to make it stronger and curved it down in a catenary so that it should not jump upward like those of Palladio. Lodoli joined this part to those under the jambs with dovetails. (Memmo ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 155–61, adapted)

Fig. 15. Window Frame, Courtyard in Cloisters, Ospizio di Terrasanta, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice (photo: Padre Rino Sgarbossa/Convent of San Francesco della Vigna, Venice).

Fig. 16. Window Sill, Courtyard in Cloisters, Ospizio di Terrasanta, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice (photo: Padre Rino Sgarbossa/Convent of San Francesco della Vigna, Venice).

Memmo also described the lintels, which are formed of catenaries too. The plan, section and elevation of the windows (Brusatin, Reference Brusatin1980: 117) give the reader a clearer picture of this invention (Fig. 17), which Memmo says was copied at his villa at Dolo by the Venetian patrician Francesco Venier (1700–1791) of the Venier branch of Sant’ Agnese (Bertazzo, Reference Bertazzo1999–2000). He was ambassador in Rome in 1740–3 to the court of Benedict XIV, where he employed Piranesi as draftsman at the Venetian embassy, and had been a prominent early pupil and close friend of Lodoli in about 1720–2.Footnote 44 In a recently discovered document, datable to 1726–7, Venier is characterized by Lodoli as ‘the most trustworthy and closest friend I have in the world’ (Cellauro, Reference Cellauro2010: 281).

Fig. 17. Plan, Section, and Elevation of the Windows of the Ospizio di Terrasanta, from Manlio Brusatin, Venezia nel settecento. Stato, architettura, territorio (Venice: Einaudi, 1980) (photo: author).

The doors connecting the rooms of the Ospizio and those opening onto the exterior gallery (perhaps more than a dozen in all) no longer survive, although one example is known from the Ziborghi engraving mentioned above (Fig. 14). Mechanics had taught Lodoli that the door jambs resting on either end of a single slab of stone eventually broke the thresholds in half. To avoid this, he divided the threshold into three parts, the first as wide as the span of the door opening, so it did not bear any of the weight of the door frame and thus was more likely to resist. He then formed a catenary curve on the underside of the centre slab and tenoned the two side slabs into it. The door jambs had wedges halfway up, connecting wall and impost, each half being given a catenary curve. Memmo noted in this respect:

Regarding jambs [Lodoli] noticed that many of them fractured, having little resistance at the midpoint when they were made too high and, pressed by the wall mass yet unable to sink, the jambs burst sideways. Therefore he made them in several parts, joining them to the wall mass itself by means of suitably dimensioned cross members which were linked to the other parts by dovetailing. Thus no part of the jambs could move out of place. (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 159)

The stability of this structure was further enhanced by the construction of a catenary curve in the arch over the door.

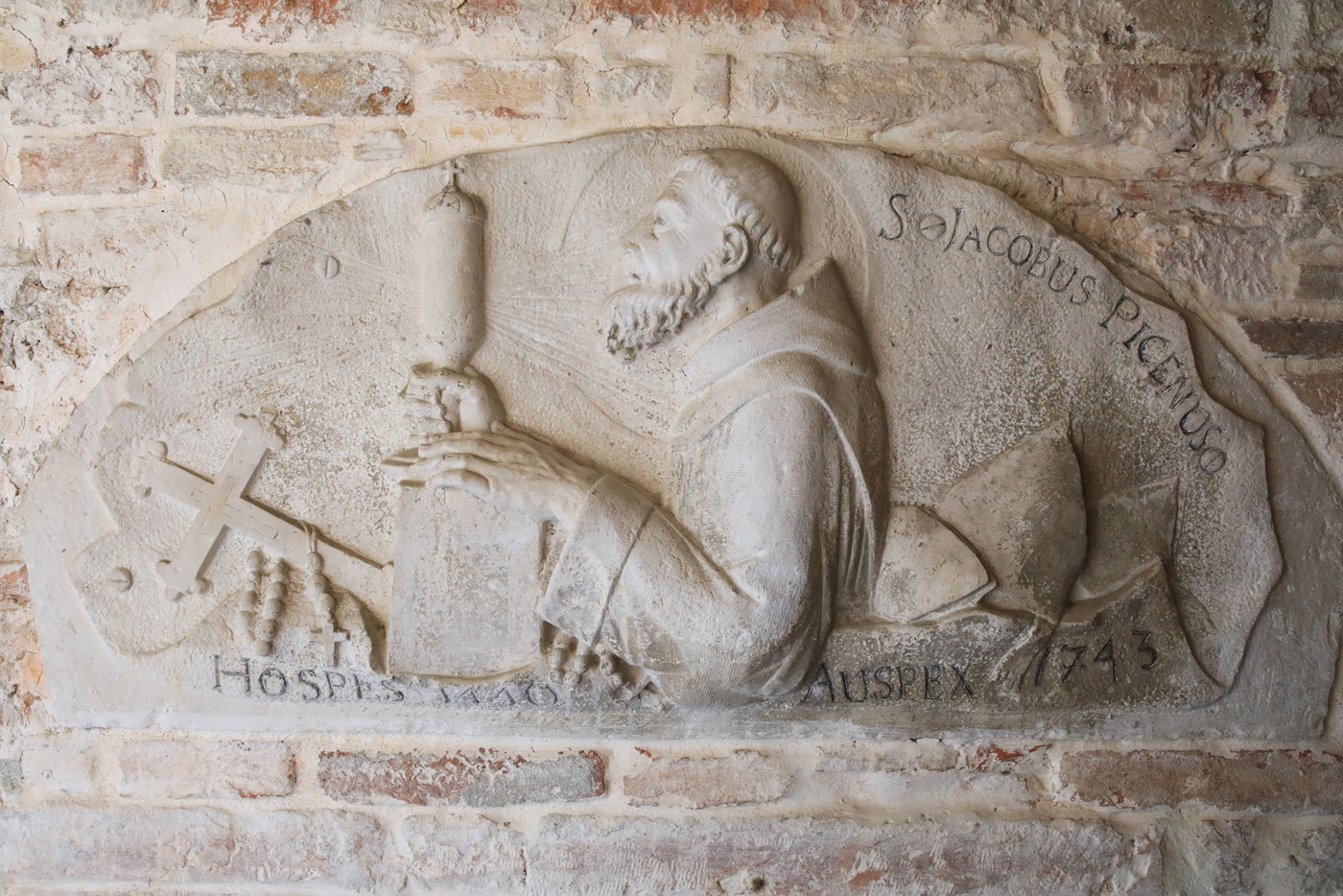

The lintel of the entrance doorway to the pilgrims’ quarters was surmounted by a carved stone (Fig. 18). It is the only clue that we have about Lodoli's ideas of architectural ornament. Memmo writes that ‘[Lodoli] had a bas-relief carved which represents the saintly patron of the friars of Jerusalem. One can note that he added four carved screwheads [as if] attaching it like a tablet or plaque. Here you see a proper application of ornament [“dell'ornato messo a proposito”]’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 158). The friars of Jerusalem were those who helped the pilgrims; their patron saint, canonized in 1726, was Jacob de Marchia or Giacomo della Marca, also known as Jacob Picenus (c. 1391–1476), shown among casually disposed emblems of religion, a shining monstrance in his right hand with his left resting on a Bible. Two inscriptions below (HOSPES 1440 / AUSPEX 1743) recall his stay as a guest at the Vigna in 1440 and his guardianship of pilgrim traffic from 1743, the date also inscribed on the foundation tablet.

Fig. 18. Bas-Relief with Jacobus Picenus, 1743, Former door lintel, Ospizio di Terrasanta, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice (photo: Padre Rino Sgarbossa/Convent of San Francesco della Vigna, Venice).

The catenary curves used by Lodoli for both the lintels and the thresholds of the windows and doors of the Ospizio were influential on other architects: they were, for example, employed by Giovanni Poleni (1683–1761), a close friend of Lodoli and Professor of Mathematics at Padua University, who used the principle when consulted on the strengthening of the dome of Saint Peter's, and whose experiments were published in the Memorie istoriche della Gran Cupola del Vaticano (Padua, 1748).Footnote 45 Lodoli and Poleni might have been aware of the recent interest among mathematicians in the catenary curve. Galileo was the first to study a catenary, although he incorrectly believed that a hanging chain created the shape of a parabola. In 1669, the German mathematician Joachim Jungius showed that a catenary shape is not a parabola. The word ‘catenary’ itself was first used by Christian Huyghens in a letter to Gottfried Leibniz dated 15 November 1690. The problem of determining its equation was put forward by Jacques Bernoulli in 1690 and was solved a year later by his brother Jean as well as by Leibniz and Huyghens in papers published in June 1691 in the Acta Eruditorum of Leipzig.Footnote 46 A few years later, the Scottish mathematician David Gregory dealt with the catenary curve in an article entitled ‘Properties of the Catenaria’, which was published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1697.

Lodoli's interest in newly discovered mathematical curves such as the catenary, combined with the obliquity of the gallery, emphasizes the anti-classical appearence of the small building. In the modest refurbishment of the Ospizio, he put into practice his concepts of a new architecture rooted in the facts of construction and the physical properties of materials in order to achieve scientific solidity and in the quest for comodità, or comfort, two of the three essential properties of representation according to Lodoli (the third being analogia, or ‘anthropometric proportion’).

CONCLUSION

Lodoli's organic architecture belongs in the context of a new concern for comfort among contemporary French architects and furniture makers. His theories of architecture and design owe much to the influence of the Enlightenment with its emphasis on reason, truth and universal criticism.Footnote 47 While the philosophers of the eighteenth century were applying a method based on such principles to politics and religion, and on occasion related architectural ideas to politics, arts and sciences (e.g. Diderot, Kant, Hegel, Schelling) (Purdy, Reference Purdy2011), several architectural writers attempted to apply these principles to architecture, although with different outcomes (e.g. Laugier). Lodoli's own ideas were greatly indebted to this new philosophical attitude. Indeed Memmo characterized him as ‘the philosopher lithologist’ ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 157), or as ‘the philosopher architect’ ([1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: II, 162), and in the first edition of Algarotti's Saggio sopra l'architettura he was never mentioned by name, but instead identified only as ‘the philosopher’.

Although Lodoli's radical and novel architectural ideas were opposed and denigrated by his Venetian contemporaries (Tommaso Temanza (Reference Temanza1778: I, 87), for example, referred to him as an ‘insolent critic and a shameless imposter’), he can be seen as ‘the prophet of rationalism’ (Wittkower, [1958] Reference Wittkower, Connors and Montagu1999: III, 7). He was probably the first theorist since the Renaissance to challenge the supremacy of classical architecture, in an age in which neoclassicism and neo-Palladianism were flourishing in Europe and in Venice. Lodoli, in fact, argued for a newer and better architecture entirely derived from the nature of materials and consistent with the law of statics, in which the architect would employ forms appropriate to each material used in order to achieve ‘truth’ or ‘function’ in architectural design. This was why Algarotti claimed that he intended to overturn ancient and modern architecture, and why Memmo reported that according to Algarotti he ‘sought to promote a complete revolution in architecture’ (Memmo, [1833–4] Reference Memmo1973: I, 33).

Architecture was not Lodoli's primary concern and he knew that his theory of truth-to-material was out of step with the taste and teaching of his day. His approach led the Venetian patrician and pornographic writer Giorgio Baffo to denigrate him as ‘a new and fanciful architect’ in the abusive sonnet ‘Quel scagazzà de Lodoli fratazzo’, written on the occasion of Lodoli's death in 1761 (Del Negro, Reference Del Negro1991: 335–6).Footnote 48 His subversive doctrine of truth-to-material, rather than his concept of organic architecture, was the most original part of his theory. His ‘organica’ was essentially the conceptualization of current Enlightenment ideas on comfort. There is a parallel with his ideas on garden design, in which he was an early advocate of the English landscape garden some fifty years before its adoption in Venice and in the Veneto, rather than being a real innovator in this field (Cellauro, Reference Cellauro2015). Thus he borrowed from contemporary culture his ideas on both comfort and garden design, whereas his revolutionary doctrine of truth-to-material was his principal original contribution to the architectural debate of the eighteenth century. Through his teaching, architectural theory in Italy achieved European significance and would have a far-reaching influence in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I started research for this paper in 2013–15 during a Senior Marie-Curie Fellowship co-funded by the European Commission and the Gerda Henkel Stiftung at the Deutsches Studienzentrum in Venice. I warmly wish to thank these institutions for this award. I am particularly grateful to Piero del Negro, who supplied detailed information on Lodoli and his circle in Venice. My deep gratitude also goes to Charles Hope, John Newman and Michael Kaufmann, who read an earlier draft of the manuscript and made a number of corrections and suggestions. Finally, the comments of the anonymous reviewers helped improve the paper considerably.