The built environment of Rome, the eternal city, did not consist exclusively of permanent monuments made of brick-faced concrete, travertine and marble: during the course of the centuries the topography was marked by many ephemeral structures that generated an imaginary cityscape and remained engraved in the viewers’ memory. In the present paper, I examine the architectural and political significance of temporary structures, as opposed to more lasting buildings, through a case study from the Fascist era (1922–43): a huge tribune, 80 m long and 13 m high (Fig. 1), originally conceived to be used for just two and a half hours during the course of Hitler's visit to Italy (3–9 May 1938) and, in particular, during the military parade of 6 May.Footnote 2 As for many historical Roman buildings, neither the project nor its decorative elements survive, but my analysis can rely on photos, newsreels, newspapers, magazines and archival documents. While discussions of Fascist military parades have focused predominantly on political and historical issues, I look at them as ‘performance’ and move the focus to ephemeral projects, spectators and urban context. Then I introduce the tribune's architect and discuss its sculptural decoration which was strongly influenced by romanità (the Roman spirit, cult, myth, tradition) (Stone, Reference Stone and Edwards1999; Nelis, Reference Nelis2011; Arthurs, Reference Arthurs2012; Kallis, Reference Kallis2014a: 73–105; Marcello, Reference Marcello, Roche and Demetriou2018). Finally, I tackle the distinction between ‘Fascism of stone’ and ephemeral architecture, a topic that has long been under-explored.Footnote 3

Fig. 1. The royal-imperial tribune in via dei Trionfi (May 1938); in the background, the Arch of Constantine and the Colosseum (photo Hugo Jaeger, The LIFE Picture Collection 50654550 / Getty Images).

The Berlin–Rome Axis of 25 October 1936, which eventually prompted the exchange of visits between Mussolini and Hitler (the former went to Munich and Berlin on 27–30 September 1937; the latter went to Italy in May 1938 for a return visit), and the Pact of Steel of 22 May 1939 resulted in a totalitarian turn for the Fascist regime.Footnote 4 A comparison between the pageantry during Mussolini's state visit to Germany and that subsequently created for Hitler would require many pages. Suffice it to say that the type of Nazi decorations used during Il Duce's visit to Germany did influence the Fascist ephemera; yet our tribune was decorated with symbols that looked back to ancient Rome and did not belong to the German tradition. The propaganda machine of the Fascist regime exploited the visual culture of ancient Rome almost to excess: the tribune was decorated with six large bas-reliefs and, except for a few isolated words (e.g. S.P.Q.R. and ROMA), impressed visually through the display of lictors’ fasces and legionary standards — relics of a romanità employed to influence the masses like the slogans of contemporary advertisements. Just as Pope Sixtus IV's symbolic ‘restitution’ in 1471 of some ancient statues to the Roman people had, in fact, reduced municipal authority and turned the Capitoline into a museum, in the same way the casts displayed at the Mostra Augustea della Romanità (1937–8) and the reliefs of the royal-imperial tribune (designed and built during the course of the Mostra Augustea) created a world of artificial spolia. The cult of romanità supported the revolutionary vision of the Fascist regime from the outset but, with many archaeological excavations and the introduction of the Fascist calendar, produced a dramatic break in time: it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to make the viewers believe that an ephemeral building such as our tribune attested to the continuity between ancient and Fascist Rome. Importantly the visual propaganda of the tribune gave concrete visibility to the march of the Fascist regime towards a glorious future. Thus, our ephemeral tribune can be considered not only to be a contribution to Fascist art and architecture but also to our understanding of the Fascist regime.

ETERNAL AND EPHEMERAL: THE NEW IMPERIAL ROME

On the evening of 3 May 1938, Hitler and Victor Emmanuel III passed through via dei Trionfi, where the royal-imperial tribune was ready for the military parade scheduled for three days later, and along via dell'Impero, which was meant to be the tribune's original setting (Fig. 2). Only by reviewing the embellishments made in, or proposed for, both roads can the tribune's significance be fully understood. Via dell'Impero (now via dei Fori Imperiali) was inaugurated on 28 October 1932. Two days later, archaeologist Roberto Paribeni suggested displaying twenty statues of Roman emperors and, eventually, the personifications of the Roman provinces (ACS, SPD, Carteggio Ordinario (1922–43), b. 379, fasc. 137307/1 (30 October 1932) and 137307/3 (9 December 1932)). Finally, on 21 April 1933 modern replicas of statues of Augustus, Nerva and Trajan joined Julius Caesar next to their respective forums. After one year exactly, the road's militaristic status was marked by four marble maps showing the expansion of the Roman Empire and, on 28 October 1936, by a fifth map depicting the Fascist empire (Hyde Minor, Reference Hyde Minor1999; Diebner, Reference Diebner2007–8; Acquarelli, Reference Acquarelli and Serra2012; Liberati, Reference Liberati2013). Bolder projects were conceived in preparation for Hitler's visit. Towards the end of 1937, engineer Raffaele Moscati envisioned two rows of fifteen Doric columns made of travertine with statues of Roman emperors on top (for a total height of 25 m), resting on pedestals decorated with reliefs representing their deeds. The ‘Arch of Il Duce’ and the ‘Arch of Augustus’ would be placed along via dell'Impero. The columns ‘seen all together could be compared to rows of huge piers of a destroyed temple without ceiling, the entrance of which would be the arch of Il Duce' and the project

could be put into practice with temporary elements (paper-pulp, gypsum) on the occasion of the visit of the Head of Germany scheduled for next spring, serve as a monumental entrance to Rome on the upcoming happy event, and offer an open field of study and observation as regards a permanent and lasting completion [of the road] with the already-mentioned stone elements. (ASC, Visita, b. 1622 (22 December 1937))

Fig. 2. Location of the tribune in via dei Trionfi (1938) and in via dell'Impero (1939) (adapted from Plan von Rom, Grieben-Verlag (Berlin 1936)). In the insets, from top to bottom: Julius Caesar (from Il Balilla 12, no. 43 (25 October 1934), 3); Hitler and Mussolini (from Il Mattino Illustrato 15, no. 19 (9–16 May 1938)); Augustus (stamp for school textbooks, 1942) (all author's collection).

As early as 1936, architect Guido Carreras had tackled this issue with a project for via dei Trionfi (now via di San Gregorio al Celio), inaugurated on 28 October 1933. He envisioned ‘great flights of marble steps allowing for the permanent layout of the areas reserved for the spectators’ and a podium for the authorities and 6,000 guests before the Antiquarium, on the future site of the royal-imperial tribune (ACS, SPD, Carteggio Ordinario (1922–43), b. 437, fasc. 167694). Via dei Trionfi was considered to be as important as in antiquity, when the legions of Rome marched along the triumphal route, and Roman triumphal processions did inspire some projects submitted before Hitler's state visit (see below). However, the military parade of 6 May 1938 had nothing to do with the Roman triumph.Footnote 5 For example, in antiquity the triumphator took an active part in the procession and there was nothing comparable to our royal-imperial tribune; moreover, the spoils of war, and not the Roman weapons, were shown to the interacting spectators (Östenberg, Reference Östenberg2009).

Contemporary photomontages populated via dei Trionfi with out-of-scale images of the German and Italian dictators or with colossal statues of Julius Caesar and Augustus (Fig. 2). The presence of those statues is less absurd than it might seem. In August 1933, while via dei Trionfi was being completed, the foundry that had just made the statues for via dell'Impero proposed to place an updated version of the Colossus of Nero next to its original location (ASC, Rip. X AA.BB.AA. (1920–53), titolo 17, classe 4, sottoclasse 5, busta 101, fasc. 11):

a bronze statue about 35 m high depicting the Fascist Colossus leaning against the Lictor's Fasces — his arm high up in the Roman salute, naked like the ancient hero or like Hercules wearing the lion skin, symbol of his victorious might … a sketch was drafted more than one year ago — a very sincere work by the great sculptor Selva — excellent — and had the honour to be presented to Il DUCE and get his approval and ‘go’. It had been conceived for another site in Rome [the Foro Mussolini].

In fact, this new colossal statue was meant to depict ‘the Likeness of He whom we all worship as the Genius of our country and of our race’. The goal was to complete it quickly (‘at Fascist rhythm’) by 21 April 1934 and place it ‘not on distant hills but in the centre of ancient Rome, which now, thanks to the will of Il DUCE, is being renewed and brought back to new glory’.Footnote 6

On the eve of Hitler's visit, architect Armando Brasini, ‘the champion of paper-pulp titanism’, submitted the project for a triumphal route based on ‘Roman imperial concepts’ (ASC, Visita, b. 1622; Cederna, Reference Cederna1979: xvii; Roscini Vitali, Reference Roscini Vitali2015). In via dei Trionfi he envisioned a series of ‘twin columns 15 m high, surmounted by Victories’ and framing huge statues of the ‘great leaders of Republican Rome, Imperial Rome and Italy’. Artist Giuseppe Ripostelli wished to rebuild the Severan Septizodium, and an anonymous citizen suggested displaying along Hitler's route 200 building cranes, resting on the Abyssinian war booty and supporting aeroplanes, that formed a sequence of ephemeral arches (ASC, Visita, b. 1622 (17 March 1938) and b. 1623). Engineer Uberto Vanghetti proposed staging Julius Caesar's triumph from Piazza Esedra to the Capitoline (with a stop at the Mostra Augustea) as well as the Ethiopian triumph led by Mussolini ‘who, from the carriage, wearing the ancient helmet of war, would greet the representative of the friendly State’ (on 12 and 16 April 1938, respectively: ACS, PCM, Gabinetto, 1937–9, b. 2414, fasc. 4/11, Prot. 3711, sottofasc. 9.13). All of these proposals were discarded because they interfered with the guidelines of the committee appointed by Mussolini as early as 10 November 1937 and chaired by Galeazzo Ciano, minister of foreign affairs (ACS, PCM, Gabinetto, 1937–9, b. 2405, fasc. 4/11, Prot. 3711, sottofasc. 1; ACS, MCP, Gabinetto, Affari Generali, b. 63, fasc. 378/7). In fact, the royal-imperial tribune was the only Fascist monument erected in the central area of the city in May 1938. One of its predecessors stood at the Ippodromo Parioli and was clearly old-fashioned (Fig. 3, left). After 1932, a tent supported by thin poles was erected on the first Sunday of June in via dell'Impero for the Festa dello Statuto (Fig. 3, right) but, after the First Anniversary of the Empire (9 May 1937), this monarchic ceremony was shifted to Piazza Venezia and lost the tribune because of the growing disappointment with royal ephemera. The president of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Costantino Patrizi, expressed his concern in a letter to Ciano and wished to solve the problem ‘in the Roman way’. He criticized the usual decorations,

not to mention the typical Royal Tribune, which is built in Via dell'Impero or in Piazza di Siena or elsewhere: suffice it to recall what was made in Rome for His Excellency the Head of the Government after his triumphal visit to Germany [an M-shaped arch covered by greenery was erected in Piazza Esedra in September 1937] to realize that those traditional elements, lacking any connections with our modern national life, are used in their essential meanness, without any sensibility for the events and without any up-to-date architectural, decorative, symbolic concepts … To fill this gap, it will suffice to submit the problem to people who are more qualified and prepared thanks to their skills, experience and previous achievements. Obviously, they must be chosen among set designers and architects. (ASC, Visita, b. 1622)Footnote 7

Fig. 3. Left: the royal tribune at the Ippodromo Parioli (10 January 1930). Right: Festa dello Statuto in via dell'Impero in 1934 (top) and 1935 (bottom) (all author's collection).

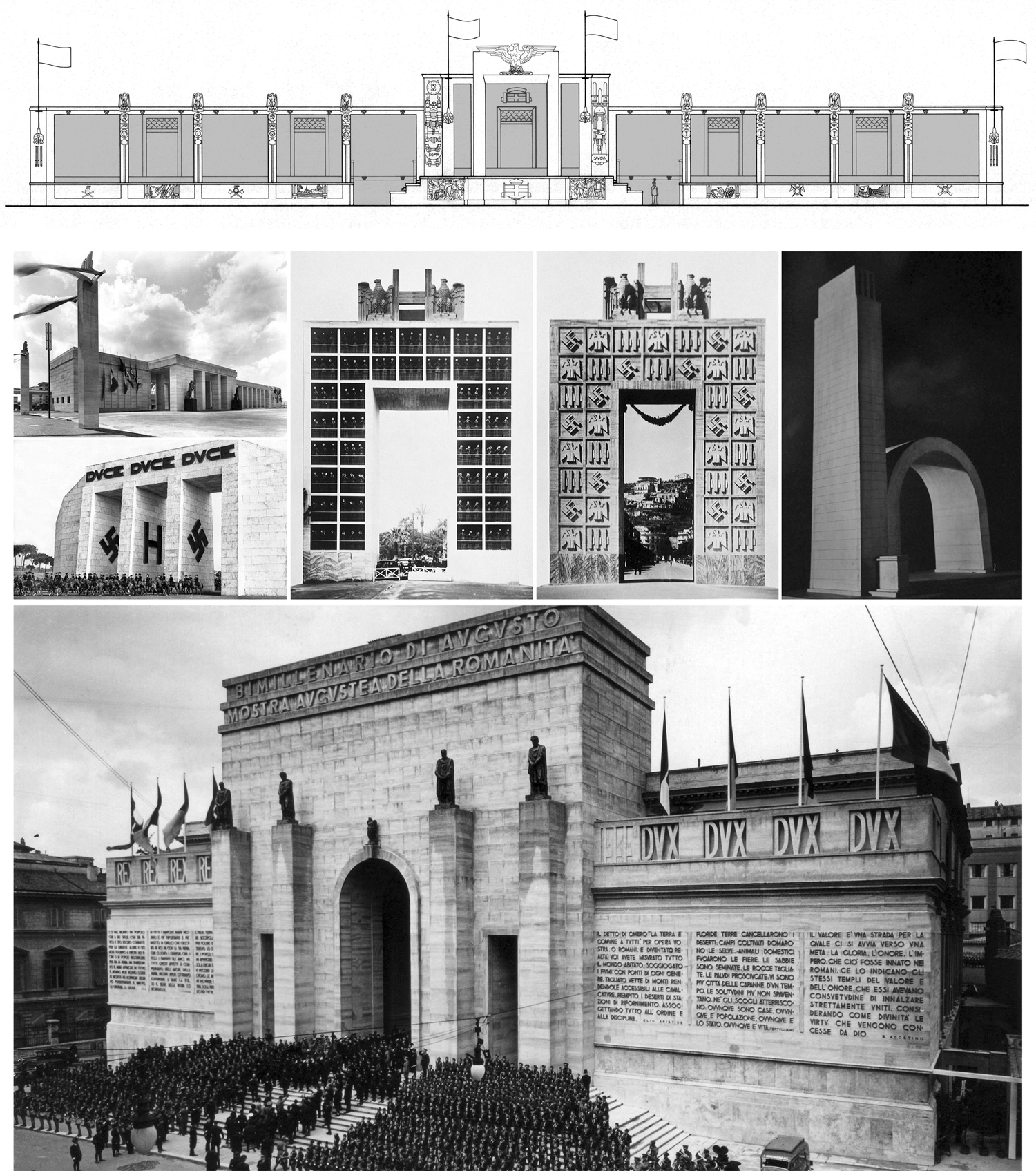

Likewise, architect Enrico del Debbio, as a member of Ciano's committee and on behalf of the Sindacato Nazionale Architetti, warned the Governatore that only the architects would guarantee ‘the appropriate style to the scenographical side of the ceremonies’. Piero Colonna replied that no architectural works were on the agenda and clarified that his administration had deliberated ‘the construction of huge tribunes at the Foro Mussolini, Piazza di Siena, and Centocelle but for events organized by the party, the Dopolavoro and the GIL [party organizations of workers and youth, respectively]’ (ASC, Visita, b. 1621, 1 and 24 March 1938). Indeed, the royal-imperial tribune (Fig. 4, top), the key element of the military parade of 6 May, was entrusted to the Ministry of War and it may not be coincidental that, after the concerns mentioned above, it looked very different from previous grandstands. Moreover, the tribune was designed and built during the course of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità, inaugurated at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni on 23 September 1937 (just before Mussolini's visit to Germany) to celebrate the Bimillenary of Augustus’ birth; the tribune's layout recalled the ephemeral façade designed by architect Alfredo Scalpelli for the exhibition, consisting of a Roman arch flanked by two wings dedicated to Victor Emmanuel III (REX) and Mussolini (DVX) (Fig. 4, bottom) (Rinaldi, Reference Rinaldi1997).Footnote 8 Ephemeral arches built for Hitler's visit and inspired by Roman architecture included a triple-bay arch at the III Campo Roma in the Centocelle neighbourhood, the top of which could be reached by means of two curvilinear stairways, and Giulio Parisio's ‘Living Arch’ in Naples, which housed 114 musicians and was crowned by the H of Hitler (Fig. 4, centre). The human presence made both arches dynamic, as opposed to the permanent arches with static sculpted figures such as the Dacian prisoners on the Arch of Constantine. The designer of the arch at Centocelle is unknown and, in general, the great names involved in the ephemera of May 1938 remain in the shadow.Footnote 9 Two months later, art critic Alfonso Gatto remarked that

on the occasion of Hitler's visit to Italy, organizers and decorators were called to a task that probably will never occur again in the future with such largeness and intensity of means. Entire cities open to the field of decoration and scenography, with natural, archaeological and monumental perspectives to be fancifully highlighted … If the scenographical and decorative ephemera, quite exaggerated as regards rhetoric and magnificence, were the precise token of the honour that the Head of the friendly nation deserved, yet they did not represent the work of the best Italian artists. (Gatto, Reference Gatto1938: 29)Footnote 10

Fig. 4. Top: elevation of the royal-imperial tribune (April–May 1938) (author's drawing). Central row: Ostiense railway station (top left); triple-bay arch at Centocelle (bottom left); ‘living’ triumphal arch at Naples (centre); project of a triumphal arch near the Ostiense railway station (right: ASC, Gabinetto del Governatore, 1938, Visita di Hitler a Roma, b. 1622; su concessione della Sovrintendenza — Archivio Capitolino). Bottom: ephemeral façade for the Mostra Augustea della Romanità (1937–8) (author's collection).

Hitler had his first encounter with Rome in a huge, ephemeral building. Indeed, on the evening of 3 May, King Victor Emmanuel III and Il Duce greeted him at a temporary version of the Ostiense station (Fig. 4, centre), which looked so real that it deceived not only the Führer but also many people who still mistake it for the present one. On either side of the entrance, called ‘a pronaos’ by a contemporary newspaper, stood two statues in fake red porphyry: ‘Statuary groups, expressing the march of Fascism and Nazism, impart, to the station's façade, the mark of romanità.’Footnote 11 The architecture of the station echoed that of our tribune: the former had ‘simple and severe lines’ and ‘the typical modern architectural style based on the canon of ancient Roman Imperial buildings’; the latter, ‘in its sober and austere lines and harmonious volumes, recalls Roman architecture’ (Calzini, Reference Calzini1938; Tosti, Reference Tosti1938). Just outside the station, on the road renamed Viale Adolf Hitler, architect Carmelo Antoci and sculptor Giovanni Cavalieri proposed to erect a lofty tower and a Roman arch recalling Hitler's initial and decorated with 86 sq. m of reliefs (Fig. 4, centre) (ASC, Visita, b. 1622 (24 March 1938)): ‘This will be the first greeting that Fascist Rome will exchange with the Head of the friendly Nation, through the language of severe architectural and sculptural forms; the latter will tell by means of great reliefs the displays of might that will take place during the visit and the deeds of the two revolutions.’

Next to the Pyramid of Cestius, on an ephemeral podium, the Governatore greeted the Führer with words that recalled a statement printed on posters, published in newspapers and broadcast on the radio on the same day: ‘Italy, powerful in weapons and combat-hardened in spirits, Roman Italy, is proud to testify her own virile admiration for the Leader of the new Reich.’Footnote 12 These words are consistent with the martial character of the royal-imperial tribune and attest to the widespread references to war in contemporary projects.Footnote 13

Next to the Obelisk of Axum just looted from Ethiopia as a war trophy (Acquarelli, Reference Acquarelli2010), two piers surmounted by eagles marked the beginning of via dei Trionfi and the entry into ‘the sacred zone of Imperial Rome’ (Il Lavoro Fascista 11, no. 104 (3 May 1938), 2). The road was flanked by candelabra that framed the royal-imperial tribune, whereas tripods made of ‘wood and stucco’ and ‘reinforced gypsum’ produced coloured flames in via dell'Impero (Mastrigli, Reference Mastrigli1938: 227–8; Longanesi, Reference Longanesi1968: 161, 211–12; Mancini, Reference Mancini2010: 51–3). Two lofty groups of legionary standards (made of ‘reinforced, fibred and patinated gypsum’) marked the extremities of the Imperial road: they were crowned by eagles and decorated with the portraits of Julius Caesar and Augustus.Footnote 14 Of course Hitler was meant to admire the ‘four marble Maps showing the phases of the dominion of Rome’ and the marble map of the Fascist empire (ACS, MCP, Gabinetto, Affari Generali, b. 63, fasc. 378/2, Viaggio del Führer in Italia (1938, Rome)).

On 6 May the Führer reached the royal-imperial tribune through a different route that allowed him to enjoy ‘the complete view of the Palatine’ and ‘the ruins of the Circus Maximus; on the horizon: the Alban Hills’ (ACS, MCP, Gabinetto, Affari Generali, b. 63, fasc. 378/2, Viaggio del Führer in Italia (1938, Rome)). He accessed the tribune from the rear side and, after the parade, heading towards the Quirinal Palace with the king, he could just see the left-hand side decorated with the navy and the air force reliefs (Il Popolo. Gazzetta della Sera 91, no. 107 (6–7 May 1938), 6). Hitler had already had glimpses of the tribune on the evening of 3 May and saw it the following day (4 May) on his way to the Centocelle airfield. A sudden change to the official schedule prevented him from seeing it one more time on the morning of 8 May, before his private visit to the Baths of Caracalla and the Appian Way. Instead Mussolini ‘inaugurated’ the tribune during the course of a test parade on 29 April (when he left it from the front). On 6 May he waited ‘in the hall that is behind’ and, some minutes later, he went down along the stairway while the crowd greeted him with applause and invocations (Il Führer in Italia (1938, Milan), 6V). Meanwhile the authorities and the carefully selected guests sitting inside the tribune could not see the façade at all: it was not conceived for their point of view. Even the protagonists of the parades could not have a detailed look at the tribune's design and decoration, unlike the spectators, journalists and photographers seated on the Palatine slope: as the minister of popular culture observed, the main concern was the ‘repercussion [in the] world press of the display of strength that we wish to give with such a ceremony’ (ACS, PCM, Gabinetto, 1937–9, b. 2418, fasc. 4/11, Prot. 3711, sottofasc. 23/1.3 (29 April 1938)). The day after the parade, even Singapore's main newspaper mentioned the ‘raised platform facing the Palatine hill and the ruined palaces of Caesar’ on which ‘Herr Hitler with King Victor Manuel and Signor Mussolini at his side took the salute from 32,000 men in a two-hour march’, who ‘represented every branch of the eight million “bayonets” which Il Duce stated could instantly be mobilised in the event of war’ (‘Hitler seeking Mussolini's aid in Czechoslovakia problem’, Malaya Tribune (7 May 1938), 11).

DESIGNING THE NEW ROMANITÀ: INTERSECTIONS OF ARCHITECTURE, ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY

On 13 April 1938 a wooden fence delimited a building site along via dei Trionfi: the construction of the royal-imperial tribune had just begun. On that day the Capo di Stato Maggiore, General Alberto Pariani, wrote to the Governatore:

Dear Prince, as you know, the military parade for the visit of the FÜHRER will take place in via dei Trionfi and the tribune of honour will be located before the Antiquarium. This was decided from the outset, after several checks, to avoid disturbing the ornamental works in via dell'Impero … Your representative in the subcommittee forbids the removal of some pine trees that fall within the area on which the tribune of honour should be constructed. Yet, we must remove them, otherwise the wings of the imperial tribune would be open precisely where the highest national and foreign authorities will sit. (ASC, Visita, b. 1621, 13 April 1938)Footnote 15

Colonna replied that the pine trees could not be removed ‘due to higher order’ (cf. Fig. 1); two days later, he realized that the Ministry of War had begun the work without any notice (ASC, Visita, b. 1621, 15 April 1938). On 26 April the construction was almost finished, but the barrack of ‘G. Ciocchetti & C.’ still stood near the tribune's left wing (Fig. 5, top). Two letters written on that day mention a request for green plants (to be placed on either side of the axial sector) and state that, with sculptor Giuseppe Ciocchetti's agreement, a decision was made to ‘floodlight the Royal and Imperial Tribune frontally’ like the nearby Roman monuments.Footnote 16 Ciocchetti's barrack was still in situ on 29 April, the day of the tribune's inauguration (inset in Fig. 5, top), and even on 2 May, the day before Hitler's arrival, when ‘the entire city of Rome paraded before the Royal Platform in via dei Trionfi’.Footnote 17

Fig. 5. Top: the tribune being constructed in via dei Trionfi on 26 April 1938, behind the barrack of G. CIOCCHETTI & C.; in the inset, the same barrack during, or slightly before, the parade of 29 April 1938. Middle: headline on the parade of 29 April 1938 (from La Tribuna 102 (30 April 1938)). Bottom: the tribune's central sector and side reliefs (adapted from La Tribuna 104 (3 May 1938)) (all author's collection).

On 29 April ‘Il Duce, First Marshal of the Empire’, attended ‘the most powerful review of armed forces ever seen’ (Fig. 5, centre): 30,000 men, 400 guns, 200 mortars, 400 tanks, 600 motor vehicles, 320 motorcycles and 2,500 quadrupeds paraded before ‘the remains of the ancient glories enlivened by the regenerating inspiration of Fascism’ (La Tribuna 102 (30 April 1938); cf. ‘Parata guerriera’, Il Popolo d'Italia (30 April 1938)). Another newspaper (Il Lavoro Fascista 11, no. 102 (30 April 1938)) chose the headline ‘One people, with its leader, with its weapons. Il Duce First Marshal of the Empire attends a spectacular display of the Armed Forces of Fascist Italy.’ Mussolini's new uniform made its appearance for the very first time, like the Roman step (that, in fact, had been tested for a few months) and the royal-imperial tribune. The article reported that:

in the middle of the Via dei Trionfi, before the municipal Antiquarium, a great platform has been erected consisting of a central sector, painted like travertine, surmounted by the royal eagle with outspread wings, and supported by piers decorated with rostra; two covered tribunes are on either side of this central platform, made of the same material, and supported by piers decorated with the lictorian symbols, while on the top cornice the reproductions of the very elegant wolf-heads of the ships from Lake Nemi alternate to this motif.

The three-hour-long parade was a ‘Test of the Military Parade’ scheduled for 6 May and implies Mussolini's approval of the tribune on the one hand and a possible conflict with Victor Emmanuel III on the other.Footnote 18 Indeed, with the law no. 240 of 2 April 1938, Mussolini had created the highest military rank in the Italian army for the king and himself. Il Duce was already minister of war, navy, air force and general commander of the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale (MVSN) but, as First Marshal of the Empire, he became the actual leader of all the armed forces. The king did not attend the test parade but responded by wearing the uniform of First Marshal of the Empire at the Ostiense station and on 6 May when, from 10.00 a.m. to 12.30 p.m., he attended the military parade in via dei Trionfi with Mussolini (wearing the uniform of the MVSN), and Hitler.Footnote 19

A newspaper exalted the ‘festivity of warlike excitement’ and the tribune that ‘recalls Roman architecture and fits in perfectly with its surroundings’ (La Tribuna 108 (7 May 1938); Tosti, Reference Tosti1938). The album Il Führer in Italia (1938, Milan: 6V) did not refer to ancient Rome but highlighted ‘the stately structure of the royal tribune, surmounted by the coat-of-arms of Savoy, the fascist lictor and the swastika’. Leaving aside La Tribuna of 3 May 1938, which published three pictures of the tribune and credited it to Ciocchetti (Fig. 5, bottom), other descriptions can be found in Il Lavoro Fascista of 7 May 1938 (a slightly revised version of the report on the parade of 29 April) and in Il Popolo. Gazzetta della Sera of 6–7 May 1938, which reported that

the great platform consists of a central sector surmounted by a big eagle with outspread wings, grasping the fasces of Rome with its talons. The central sector, supported by rostral piers, has superstructures that simulate the Roman travertine effectively. Beside the platform, two spacious, covered tribunes — packed with a large public — are connected with the central platform by means of architectural elements bearing the symbols of the ancient and new romanità in bas-relief, and medallions with legionary standards.Footnote 20

Capitolium, the official magazine of the Governatorato, commented that ‘one of the most common effects that these ephemera usually produce is a rapid sense of tiredness’ but, during Hitler's visit, all the events ‘left an unforgettable memory in everybody, and a lively desire to see some of these decorations become definitive and permanent’: for instance, ‘the majestic Royal Tribune built in front of the Antiquarium, with the travertines perfectly in tune with the black backdrop of the little cypresses and the cluster-pines’ (Mastrigli, Reference Mastrigli1938: 231–2). La Tribuna, too, proposed to turn most of the ephemera into permanent features because, in view of the E42, the triumphal and imperial roads would mark ‘the official entranceway of illustrious guests’ (‘Realizzazioni che rimarranno’, La Tribuna 110 (10 May 1938), 6).

The designer of the royal-imperial tribune was the already mentioned Giuseppe Ciocchetti (1883–1963).Footnote 21 The choice of a minor figure on the architectural scene was not due to the nature of the commission, because many Italian architects specialized in ephemeral structures.Footnote 22 As we shall see, Ciocchetti was in the right place at the right time. His headquarters was the Palazzina Ciocchetti, built in 1923–30 and located in via Tiburtina 140 (now 108–114) (ASC, Commissione Edilizia, Verbali della C. E., vol. 57 pag. 452 (prot. 6531/1923); ASC, Rip. V LL. PP., Ispettorato Edilizio, year 1930, prot. 13438/1930). From 1922 he had promoted his workshop, L'Arte Funeraria, with postcards and publications. His second catalogue, entitled Cav. Giuseppe Ciocchetti Scultore-Architetto and published around 1927, advertised 60 monuments to the fallen soldiers of World War I (some of which anticipate subjects and poses visible in the tribune) and many public monuments built in 1925–6 in Italy, England and America.Footnote 23 Significantly, in 1927 the minister of public education stated that ‘too many monuments, often in contrast with art, decorate the squares and streets of Italy. The Fascists, from now on, instead of monuments should dedicate houses to the fallen soldiers’ (P. Fedele, ‘Non monumenti ma asili’, Foglio d'Ordini of the Fascist Party; Cresti, Reference Cresti1986: 42). The regime wished to promote a new form of memory and Ciocchetti had to rethink his own career.

The turning point can be fixed around 1927–30, when he founded the ‘Società Anonima G. Ciocchetti & C.’.Footnote 24 Eventually he was constantly associated with the Ministry of War, as revealed by a dossier that lists, among many of his works, the ‘monumental Tribune of the delegations, built in 1938 and in few days in Rome on the Via dell'Impero [sic]’ (ACS, MPI, Direzione Generale Antichità e Belle Arti (1852–1975), Divisione III (1940–60), b. 445, fasc. Museo delle Arti e Tradizioni (danni di guerra), folder ‘S. A. G. CIOCCHETTI & C.’; Fabbri, Reference Fabbri and D'Agostino2018). Just before Hitler's visit, Ciocchetti had been involved in the construction of the Istituto Storico di Cultura dell'Arma del Genio, designed by Gustavo Giovannoni and Cesare Valle in 1936 and begun on 20 March 1937. He was one of six contractors who submitted an estimate, but the Ministry of Public Works observed that he did not possess the necessary skills (ACS, MLP, Div. 18, b. 350 B, fasc. 140 (the architects are mentioned on 11 February 1937)). Nevertheless, he was awarded the contract and, as reported in the dossier, he made ‘all the great works in travertine and precious marbles, the great artistic doors in bronze, the sculptures, the mosaics, the twelve large high-reliefs in marble depicting the various specialties of Military Engineers’. The analogies with the tribune are evident: beside the Savoia coat of arms overlooking the main entrances, note the ancient and modern trophies on the frieze facing the courtyard (Fig. 6), the twelve marble reliefs in the atrium and the wall mosaic entitled ‘The Pioneer’ in the main hall of the first floor (Fig. 7) (which still houses a marble copy of the statue of Julius Caesar, with Ciocchetti's signature), and the eagles at the entrance to the Sacrario (see Fig. 10 further below). The mosaic depicts two legionaries, Roman and Fascist, holding a golden standard crowned by an eagle; among the silver objects behind is a round shield with a Gorgon, also present in the royal-imperial tribune. Other commissions from the Ministry of War include the Palazzo degli Alti Comandi Militari (1935–8), for the courtyard of which Ciocchetti made another marble copy of Julius Caesar's statue, and the tent city in the Parioli neighbourhood that housed ‘40,000 fighters gathered in Rome for the celebrative parade of the Twentieth Anniversary of Victory’ in November 1938.Footnote 25

Fig. 6. Rear façade of the Istituto Storico e di Cultura dell'Arma del Genio, Rome; note the tripartite passageway, the frieze on the balcony, and the ‘Mussolinian’ heads above (photo: author).

Fig. 7. Istituto Storico di Cultura dell'Arma del Genio, Rome. Left: three reliefs by Ciocchetti displayed in the atrium (note the bridge of boats in the middle); right: Ciocchetti's mosaic depicting ‘The Pioneer’ on the first floor (both photos: author).

Leaving aside the funerary chapels designed in his early career, the royal-imperial tribune appears to be Ciocchetti's major project (although he might be responsible for the decorative elements only). First-hand information on his sources of inspiration is provided by the preface to his third catalogue, where he boasts of his knowledge of Egyptian, Greek and Roman funerary monuments, stresses the importance of their symbols and reliefs, and highlights ‘the love for art in general and for funerary art in particular, to which we devoted many years of tireless study and careful meditations and observations, visiting the most famous and monumental cemeteries not only in Italy but also in Europe’ (Ciocchetti, Reference Ciocchetti1927: preface). In addition, he mentions his mastery of the construction process; not by chance, a letter of reference written on 25 July 1938 by the Ministry of War, and attached to the dossier cited above, praises Ciocchetti's ‘great artistic and technical competence shown in the construction of the tribune … with zeal and technical capacity, overcoming considerable difficulties due to the extremely short time available’.Footnote 26 Nevertheless, the same letter does not mention the reasons why an obscure 55-year-old artist was entrusted with such a prestigious commission. An answer can be found in a secret report by the Political Police drafted on 31 May 1938, three weeks after Hitler's visit (ACS, MI (1814–1986), Direzione Generale Pubblica Sicurezza (1861–1981), Divisione Polizia Politica (1926–45), fascicoli personali (1926–44), b. 303, fasc. ‘Ciocchetti Ditta.’):

It is common knowledge that the Great Official Ciocchetti on the occasion of Hitler's visit was entrusted with many works to be made in Rome. Chiocchetti [sic] does not conceal that he got those works thanks to General Dall'Ora Giuseppe, director of Military Engineers, and a certain Consul Mario Mingoni [di Siroc], towards whom he has been more than generous, of course. Indeed, it is said that Gen. Dall'Ora's house looks like a branch of Ciocchetti due to the many statues, little fountains and other works of sculpture that fill it. It seems that he has enjoyed the protection of Consul Mingoni for a long time. Indeed, none of Ciocchetti's acquaintances is unaware that one of his sons, recalled to arms for the war in East Africa, was helped by Mingoni and did not leave. Ciocchetti himself boasts of this fact and adds that, as far as he is concerned, war can even break out tomorrow since neither son of his will fight because he can get everything with money.

Ciocchetti himself had been exempted from World War I at the age of 32 (ASC, Titolo 61. Campo Verano e Cimiteri, 1918, b. 115, fasc. 198 (prot. 17337/1918)). Although involved in monuments and buildings related to war, during the course of his life he had no experience of war at all (except for the Allied bombing of the San Lorenzo district, his own neighbourhood, in 1943). Another paradox is that, while his funerary monuments were meant to be eternal, the royal-imperial tribune was designed to last for a couple of hours.

This ephemeral grandstand consisted of a central sector (the main tribune, including porch and rear hall) and two side porticoes organized in a symmetrical composition (cf. Fig. 4, top).Footnote 27 It echoed the entranceway of the Ostiense station and the triple-bay arch at Centocelle, as well as Marcello Piacentini's Rectory at the Città Universitaria (see Fig. 15 (top) further below), which stood near Ciocchetti's headquarters.Footnote 28 It was also reminiscent of the Barracks of the Fourth Legion Mussolini (1932–5), designed by architect Gaetano Minnucci and once located behind Piacentini's Rectory, consisting of a slightly curved building with axial stairway and arengario flanked by two low wings articulated in five bays (Marcello and Gwynne, Reference Marcello and Gwynne2015: 337). Yet, showing a taste for quotations, Ciocchetti not only created a modern pastiche of a temple's pronaos and porticoes, he also turned the pulvinar reserved for the emperors’ epiphany in the Circus Maximus and the enclosure of the Ara Pacis Augustae in the Campus Martius, with its panels and processional friezes, into key elements of the tribune. Other visual references to ancient Rome included rostra, trophies, lictor's fasces, legionary standards, and wolf-heads that, together, recalled the casts on display at the Mostra Augustea della Romanità. Despite the frontal staircases, the axial sector was accessible from behind through a stairway leading from the Antiquarium down to a back hall. The main doorway was surmounted by a rectangular window (as in the Pantheon) and by the Savoia coat of arms flanked by lictor's fasces that replicated the emblem topped by the royal crown in the central parapet. Another four doorways gave access to the seating area. One or more inscriptions, perhaps recalling the VOTIS X carved on the nearby Arch of Constantine, should have marked the date of Hitler's visit according to the Fascist calendar but, just before the inauguration, it was noted that ‘on the piers of the tribune of honour in Via dei Trionfi it is written, probably by mistake, ANNO XIV [1936] instead of XVI [1938]’ (ACS, SPD, Carteggio ordinario, 1922–43, b. 475, fasc. 183.258/3 (27 April 1938)). My guess is that the mistaken dates were inscribed on the lowermost tablets of the piers’ legionary standards (see below).

The tribune had no foundations and consisted of a scaffolding veneered with slabs of travertine (at least in the central sector). The fact that it was ‘painted like travertine’ suggests the use of panels of ‘carpilite’, an autarchic material made of wood shavings agglomerated with a cement mixture and finished with metal brushes — a technique developed in 1937 on the sets of the movie Scipione l'Africano. Their layout recalled the ancient opus quadratum, which explains why the Ostiense station looked ‘entirely made in Roman travertine worthy of the Urbs’; completed in 45 days and ‘proud to live just the hour for which it was designed’, in fact the station's structure consisted of a forest of Innocenti tubes covered by wooden planks and carpilite panels.Footnote 29 As for our tribune, two pictures taken in 1938 and 1939 (when the tribune reappeared on the scene) show that its slabs were reused in exactly the same position (cf. the veins in Fig. 8), which means that, after Hitler's visit, all its pieces were carefully numbered and stored in order to be reassembled.

Fig. 8. The veneer of the tribune in via dei Trionfi (1938) (left) and in via dell'Impero (1939) (right); note the slabs placed in the same position (both author's collection).

An eagle with outspread, horizontal wings, looking left and grasping a sceptre (‘the fasces of Rome’, according to Il Popolo. Gazzetta della Sera of 6–7 May 1938), dominated the tribune (Fig. 9, top). Despite the absence of the Savoia crown and coat of arms, Il Lavoro Fascista of 7 May 1938 identified it with the ‘royal eagle’. In fact, it was the symbol of the Ministry of War, as on the brochure of the parade of 6 May (inset in Fig. 9), but could allude to the Reichsadler of Nazi Germany as well. Eight smaller eagles with vertical wings stood on top of the piers’ legionary standards (Fig. 10, left). Their meaning is clarified by a book on Augustus and Mussolini published in 1938 (De Castro, Reference De Castro1938), the cover of which shows eagle-topped standards and swords (likewise present on the tribune) with the motto ‘The eagles of Rome sweep again in the sky of the City foreboding the new goal’. During the course of Hitler's visit, similar eagles decorated the Ostiense station and its outer square, the piers located at the beginning of via dei Trionfi and the wall opposite the Colosseum, the entrance to Termini station, the future Olympic Stadium and two lofty pillars at Centocelle. Ciocchetti himself had placed two eagles at the entrance to the Sacrario of the Istituto Storico del Genio (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9. Top: the tribune in via dei Trionfi during the parade on 6 May 1938 (author's collection); in the rectangular inset, location of the musicians (ASC, Gabinetto del Governatore, 1938, Visita di Hitler a Roma, b. 1623; su concessione della Sovrintendenza — Archivio Capitolino); in the circular inset, the eagle of the Ministry of War, from Roma 6 Maggio XVI / Rivista Militare in onore del Führer Cancelliere del Reich (1938, Milan) (author's collection). Bottom: plan of the tribune on the same axis as the Antiquarium (ACS, Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, Gabinetto, 1937–9, b. 2419, fasc. 4/11, prot. 3711, sottofasc. 23.2.1).

Fig. 10. From left to right: first pier in the left wing of the tribune in via dell'Impero (10 June 1939) (author's collection); pier topped by an imperial eagle at the entrance to the Sacrario of the Istituto Storico del Genio, Rome (photo: author); pier of the Palazzo dei Musei in Rome (photo: author); legionary standards in via dell'Impero on 6 May 1938 (from a postcard); cover of ENIT, Visions of Imperial Rome (1937, Milan); postcard of the Gruppi d'Azione Tunisina (author's collection).

Two bows with rostra were fixed to the side piers of the tribune's porch and to the larger piers at the porticoes’ side extremities, alluding to ancient Roman warships and to the rostra in the Forum. They supported the poles of the waving flags of Germany and Italy, a dynamic décor that recalled the floating banners placed along Rome's streets, whose colours must have attracted the spectators: the tribune was completely white except for the green frame of the axial doorway (in fake cipollino marble?), the green plants, and the crimson drapery of the podium — the colours of Italy. The trophies on the vertical, transitional joints depicted the equipment of both an ancient Roman and a contemporary legionary (cf. Figs 9 and 19 (further below)): these ‘symbols of the ancient and new romanità’ (see above) were dedicated to Rome and the Savoia, and buttressed, metaphorically, the tribune's axial sector. On the left-hand side, from bottom to top, one could see a curvilinear shield called a pelta bearing the inscription ROMA and overlapping two swords, in their turn concealing a vexillum; at mid-height was a cuirass with a helmet flanked by legionary standards topped by eagles that supported a shield. Meanwhile, the trophy on the right-hand side had the inscription SAVOIA on a tabula ansata that overlapped the Savoia knot. The duality Roma–Savoia echoed the ephemeral façade of the Mostra Augustea where, however, the word DVX was opposed to REX. Because of the coexistence of Roman, Fascist and royal symbols, Ciocchetti's tribune can be seen as a hybrid monument that captured the spirit of the Fascist revolution through classicizing images that spoke to the memory of the Italian people, accompanied by modern reliefs of the armed forces (described below) attesting to the aspirations of the Fascist regime. Together, they played a fundamental role in the creation of a new national identity.

The four piers that divided each side wing into five bays were decorated with legionary standards (Fig. 10, left), which Ciocchetti used like an architectural order. During the Ventennio they were widespread (Fig. 10), especially during the course of Mussolini's speeches (Fig. 11), but the only examples in stone that survive from Fascist Rome are carved on the porch of the Palazzo del Museo (ex Pastificio Pantanella in via dei Cerchi) (Fig. 10). Like the trophies, the tribune's legionary standards related to Rome and the Savoia. On the left, three tabulae ansatae of decreasing size contained the inscriptions ROMA and S.P.Q.R. (the lowermost was blank, probably to conceal the mistaken date mentioned above), with two intermediate roundels bearing the portrait of a Roman emperor (Augustus?) and a frontal Gorgon who, in classical mythology, had the power to petrify the viewer with her gaze. The opposite set of legionary standards had ITALIA carved on top and FERT (the acronym engraved on the collar of the Ordine della Santissima Annunziata, one of the highest distinctions of the Savoia dynasty) in the middle; the portrait depicted a bearded man (King Victor Emmanuel II?). Two groups of three lictors’ fasces, orthogonal to the surface and with axes below, framed the entire tribune at the extremities. Finally, 32 wolf-heads decorated the side staircases and the architraves of the side porticoes (note that in 1939 four were removed from the bays closer to the axial porch); their models were the bronze wolf-heads recovered from Caligula's ephemeral ships at Lake Nemi in 1928–32 (Giglioli, Reference Giglioli1938: 223. Cf. ‘I bronzi e le miniature alla Triennale’, Domus 11, no. 67 (July 1933)).

Fig. 11. Left: legionary standards on Mussolini's tribune at Porta Bra, Verona (18 September 1938) (author's collection); right: the second tribune in the same location (L'Illustrazione Italiana 40 (2 October 1938)).

The royal-imperial tribune was dedicated to the king-emperor but was conceived for Il Duce and the Führer (note the two Nazi flags); therefore it should be examined in its Italian political context — the conflict related to the rank of First Marshal of the Empire — and in the light of international events. However, because the focus of the present paper is the design and reception of the ephemeral tribune, it must be stressed that in May 1938 the most important cultural event in Italy was the Mostra Augustea della Romanità. Apparently, classical images legitimized the Fascist regime by overlaying the monumental patina of romanità onto the tribune. At the exhibition, in the ‘Hall of the immortality of the idea of Rome. The rebirth of the empire in Fascist Italy’, a Mussolinian quotation read: ‘Rome is both our starting point and our point of reference, it is our symbol or if you like our myth. We dream of a Roman Italy, that is wise and strong, disciplined and imperial. Many aspects of the immortal spirit of Rome are reborn in Fascism’ (Giglioli, Reference Giglioli1938: 369, XIX). The curator of the exhibition added that ‘all Italians, by means of the Mostra Augustea, will be able to experience readily our people's glorious first Empire’ (Giglioli, Reference Giglioli1938: xvi). Both statements suggest that the visitors were trained to interpret the casts on display and then would be able to recognize the symbols of romanità in Ciocchetti's tribune: the ultimate goal was the education of the masses (Nicoloso, Reference Nicoloso2011). A growing body of scholarship has focused on the iconographical symbolism of ephemera in the context of the large-scale pageantry of a temporary event (Bonnemaison and Macy, Reference Bonnemaison and Macy2008). It must be admitted that Fascist parades and ephemera were not cryptic at all: in May 1938 any citizens and visitors would have recognized the biga and the Victory on the tribune's central panels and the other symbols thanks to the visual propaganda made by the Fascist regime through coins, stamps, postcards, textbooks and especially the Mostra Augustea della Romanità.

In the 1930s many artists called for a return to bas-reliefs, frescoes and mosaics as forms of art to be integrated with architecture to perform educational and political functions. As a sculptor and an architect, Ciocchetti could easily achieve this aim, as evidenced by the six reliefs that decorated the tribune's parapet. Unlike his twelve marble reliefs visible at the Istituto Storico del Genio, those displayed on the tribune were made of gypsum, like the casts of the Mostra Augustea: they had no inscriptions but only easily recognizable images because their message had to be clear, with visual elements taking precedence over words so that the viewers could traverse two millennia with a single glance. They were not made to last physically but to impress upon the mind. The central sector featured two processions (about 1.70 by 3 m) converging toward the tribune's axis and reminiscent of the enclosure of the Ara Pacis Augustae that Hitler and Mussolini admired on 7 May while it was being restored at the Museo delle Terme (Fig. 12). As in the Augustan monument, there were also four individual panels, inserted into the side parapets and measuring about 1 by 2 m. Yet, their theme was not peace but war. They depicted the armed forces and were framed by short swords (alluding to the gladius of the MVSN?) alternating with the emblems of various corps (Fig. 13).

Fig. 12. Hitler and Mussolini viewing the northern frieze of the Ara Pacis Augustae being restored at the Baths of Diocletian (7 May 1938) (from P. Chessa, DUX. Benito Mussolini: una biografia per immagini (2008, Milan), 265).

Fig. 13. Top: Ciocchetti's reliefs (clockwise, from top left): air force (photo Hugo Jaeger, The LIFE Picture Collection 50654556 / Getty Images); navy (50654571); military engineers (50654569); artillery (50654570). Bottom (clockwise, from top left): air force, navy, artillery, army (from PNF, Il secondo libro del Fascista (1940, Rome), 90, 86, 84, 82, respectively).

The sequence of the panels (cf. Fig. 4, top) can be reconstructed only thanks to photos and newsreels dating from April–May 1938 and May–June 1939.Footnote 30 From the centre to the right-hand side extremity could be seen the artillery and the military engineers reliefs.Footnote 31 The former depicted a tank and six shotguns with bayonets and triangular flags that might be associated with the pre-military corps of the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio (GIL). The latter was characterized by a howitzer placed between projectiles and a wooden bridge on boats alluding to the Pontieri, specialized in the construction of such ephemeral structures (cf. the relief at mid-height in Fig. 7, left).Footnote 32 On the left-hand side of the tribune, from centre to left one could see the navy and the air force reliefs.Footnote 33 The anchor and the four battleships in the navy relief recalled the display of 5 May in the Bay of Naples whereas the air force relief, depicting aeroplanes rising up in a cloudy sky, announced the display of 8 May at Furbara. In 1937, a booklet that celebrated the first anniversary of the Fascist empire devoted two pages to the army, one to the navy and one to the air force, precisely like the tribune's reliefs. In 1940, the last four illustrations of a publication by the Fascist Party that stressed Italy's might on land, sea and in the air matched Ciocchetti's reliefs even more closely (Fig. 13): the relevant captions read ‘Parade of fast tanks’ (photo taken in via dell'Impero), ‘Battery of truck-drawn guns’ (likewise in via dell'Impero), ‘Naval squadron in navigation’ and ‘Aerial squadron in navigation’ (PNF, Il secondo libro del Fascista (1940, Rome): 82, 84, 86, 90; also 80).

These reliefs, which seem to announce the Pact of Steel, can even be associated with the myth of war of Futurism and, from a stylistic point of view, are a good example of Fascist ‘aesthetic pluralism’. In 1931, dealing with Gherardo Dottori's paintings at the water airport of Ostia that show a ‘violent rush of airplanes in the sky of Rome with propellers, fuselages and transfigured wings’, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti observed that the traditional eagles (like those placed on the tribune), ‘far from glorifying aviation, today look like miserable chickens compared to the torrid, mechanical splendour of a flying engine that certainly disdains to roast them’ (Marinetti, Reference Marinetti1931; Orazi, Reference Orazi1931). Three years later, Fortunato Depero (Reference Depero1934) claimed that the Futurists ‘love the brand-new weapons and a modernity pushed to its extreme conclusions. They create works filled with a building Fascism, powerfully armed, populated with harrows, sowing machines, guns, airplanes, rifles and assault tanks.’ During the parade of 6 May it was possible to hear the sound of the ‘aerial squadrons that, as a token of honour, make large circles around this area’ and ‘speed quickly along the route of the royal procession, sometimes go down very low, then throw themselves up again in the sky, which they fill with their powerful roar’, while ‘the gun makes us hear its low voice at equal intervals’.Footnote 34 If each individual relief was a celebrative monument in itself, all four in sequence, depicting objects oriented as the flow of the parade (beginning with the wooden bridge on boats that recalls the ephemeral bridge by Apollodorus of Damascus carved at the bottom of Trajan's Column, and ending with the aeroplanes), suggested a progression toward the future comparable to the accelerated expansion of Rome offered by the marble maps of via dell'Impero.

The twin processional reliefs (Fig. 14) might have alluded at the same time to the March on Rome, to the Fascist revolution and to the Ethiopian military campaign. Like the reliefs visible at the Istituto Storico del Genio, both processions were characterized by action and movement. Ciocchetti carved two scenes never seen in everyday life (note the duplication of Victory) to highlight that Fascist Italy was on the march toward a glorious future under the reassuring shadow of romanità. On the left-hand side relief, one could see four contemporary fully dressed soldiers, a winged Victory with laurel crown, an almost naked leader on a biga decorated with acanthus scrolls, and a Roman legionary holding two restive horses. The nearest (literally) ancient model was the bas-relief of the Arch of Titus depicting the emperor's triumph over Judaea in AD 71.Footnote 35 The right-hand side relief showed the winged goddess followed by nine men: bare-chested Fascist and ancient Roman legionaries who call to mind not only the passo romano but also Brasini's proposed statuary groups along Hitler's route, just before via dei Trionfi: ‘on one side, the legionaries of the two regimes, on the other two legionaries wearing the Roman and Germanic costumes of the time of Augustus’ (ASC, Visita, b. 1622). A curved joint created a break between the tribune's reliefs and the protruding parapet; thus, the two horses on the left and the Victory on the right shared the viewers’ space. Apparently, Ciocchetti directed the spectators’ gaze toward the authorities and, as in the case of the axial eagle, gave the twin processions multiple levels of reading. In combination with the reliefs of the armed forces, which display no engagement with the classical world, they symbolized two events, war and revolution, that according to Fascist culture would mark a new era.

Fig. 14. The processional reliefs of the tribune. Left: Triumph (photo Hugo Jaeger, The LIFE Picture Collection 50654557 / Getty Images); right: Victory (50654572).

The Roman and Fascist legionaries were as high as the Corazzieri (cf. Fig. 9) and the Blackshirts (see Fig. 17 further below), and echoed the ‘Hall of the Army’ at the Mostra Augustea, where a reviewer (Caroselli, Reference Caroselli1938) was struck by the ‘piers with arms, insignia, trophies, decorations for valour, weapons, and the striking sequence of the XXX Legions, which in their regular succession give an idea of the impressive Roman might, as the rhythmical step of the victorious legions marching along the Appian Way in the last movement of Respighi's Pini di Roma [1925]’. Ciocchetti's tribune was inaugurated shortly after the introduction of the Roman step and appears, once again, to be connected to the Mostra Augustea where, moreover, the image of Victory was ubiquitous.Footnote 36

As the imagery of the royal-imperial tribune mirrored its ancient topographical context, it might be useful to note the similarity of the tribune itself to the depiction of a highly hierarchical pavilion carved on the fourth-century AD frieze of the nearby Arch of Constantine and, in reality, erected in the Forum of Caesar on 1 January AD 313 for Constantine's distribution of public largess (Fig. 15, bottom). The carved architecture does not represent the Forum of Caesar at all and must have been ephemeral. Thus, there would be a surprising precedent for Ciocchetti's grandstand that, like the Arch of Constantine, seems to display spolia — legionary standards, trophies, wolf-heads, swords, lictors’ fasces, and reliefs — taken from older monuments. The tribune's parapet with its reliefs and emblems is also reminiscent of the balustrades of the scholae cantorum installed in medieval churches: it might not be exaggerated to consider the royal-imperial tribune as a cult building for the Fascist religion of the Third Rome, like the temple in the Rome of the Caesars and the church in the Rome of the popes. The tribune appears to have been designed as a monument that translated politics and religion into architectural and sculptural forms: its axial porch was a sort of pronaos in which, on 28 May 1939, Mussolini was worshipped like an actual emperor (see Fig. 18, further below) materializing Terragni's vision of his ‘epiphany’ on the arengario of the Palazzo del Littorio: ‘the attention of the people towards the Podium is absolute; everybody will see Il Duce outlined against the sky’ (‘Concorso per il Palazzo del Littorio’, Architettura 13, special issue (1934), 37).

Fig. 15. Top: Piacentini's Rectory at the Città Universitaria in Rome (1936) (photo: author); bottom: congiarium in the Forum of Caesar on 1 January AD 313 (from the fourth-century AD frieze of the Arch of Constantine) (photo: author).

EPHEMERAL ARCHITECTURE AND FASCISM OF STONE

By examining the socio-historical and political meanings of the royal-imperial tribune's visual imagery it is possible to understand the workings of Ciocchetti's mind within the artistic conventions of the Fascist era and how viewers understood the tribune's reliefs. The representations of navy, air force and army could be taken as symbolic depictions of future military campaigns at sea, in the air and on land. The trophies and the twin processional reliefs corroborated an unmitigated message about the might of Fascist Italy already inherent in the actual parades. The other motifs — legionary standards, ship bows and wolf-heads — encouraged viewers to reflect on the intersections of ancient and new romanità within a vibrant set of topographical stimulants.

As for the place of the royal-imperial tribune within contemporary architectural debates, it is worth recalling that in 1932 Mussolini had ordered the architects involved in the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista to design something ‘very modern and bold’ in opposition to ‘a Romanizing solemnity roughly veneered with false travertine’; subsequently the director of the exhibition, Dino Alfieri, approved De Renzi and Libera's ephemeral façade brandishing four huge, metal fasces.Footnote 37 In December 1933 the contest was announced for the Palazzo del Littorio in via dell'Impero, which would house the headquarters of the Fascist Party, the permanent exhibition of the Fascist revolution, and a shrine to the fallen Fascists (Marcello, Reference Marcello2007; Rifkind, Reference Rifkind2007). Archaeologist Antonio Muñoz (Reference Muñoz1935: 220–1) stated that ‘the colonnades of the Pantheon, the triumphal arches, the domes, the spires, the statues, the chariots would not have worked’ and stressed that ‘one of those architectural boxes which are today in style, especially across the Alps, would not have been tolerated’. According to architect Giuseppe Pagano (Reference Pagano1934a), two worlds faced each other in that contest: ‘the static one, in love with form and pomposity, which declares itself to be the defender of romanità … and a progressive and lively one, which finds its health in the rude and eternal purity of the simple things and will express the ideal of the modern Italian through today's measurements and rhythms, without turning to the size of the dinosaurs, to boastful rhetoric or to Vitruvius’ equations’. He did not submit a proposal because it was impossible to reconcile the ‘corpses of ancient Rome’ with the ultimate symbols of Fascist civilization (Pagano, Reference Pagano1934a, Reference Pagano1934b, Reference Pagano1934c). Just four years before Hitler's visit Ciocchetti's tribune, with its symbols of romanità, would have been out of place in via dell'Impero; eventually it became the only Fascist building erected there.

In the late 1930s, countless buildings in Rome and across Italy were built in the ‘Stile Littorio’ exemplified by the guidelines of the second contest for the Palazzo del Littorio (1937), which would ‘mirror the artistic evolution of the current historical period but at the same time connect to the noble traditions of great Italian art. Its lines must express an elegant and efficient sobriety and yet keep its distance from any kind of excessive or loud display of ostentation. At the same time it must have the characteristics of Roman monumentality’ (‘Il concorso di secondo grado per la Casa Littoria in Roma’, Architettura 16, no. 12 (December 1937), 703). This neo-imperial architecture employed traditional materials such as brick and travertine, made use of porticoes and stark symmetries, simplified elements (e.g. columns and piers without capitals), but was often enriched with reliefs and Latin inscriptions (Ghirardo, Reference Ghirardo1980). Two and a half months after the appearance of Ciocchetti's tribune in via dei Trionfi, Piacentini (Reference Piacentini1938) praised ‘the return not to the shapes of past styles but to the elementary forms of our spirit and our race, to the divine harmony, to clarity, to nobility’; he was not against classicism but, rather, against a pedantic use of the architectural and decorative styles of the past (Nicoloso, Reference Nicoloso2011: 200–4). However, the Fascist regime continued to sanction different styles: what changed was the restriction of scenarios in which rationalist architecture was used (e.g. post offices, railway stations, etc.).

What made our tribune different from Fascist permanent architecture (and from other ephemeral works) was the coexistence of symbols of romanità and futuristic subjects in a ‘monument’ that might be the exception to the rule also because its author was a sculptor rather than an architect. The other tribunes of the late 1930s were characterized by aggressive shapes and didactic images that could be easily understood by the masses, since they magnified blatantly explicit symbols (such as the fasces or the M of Mussolini) or ancient building types (e.g. the honorary/triumphal arch) (Cresti, Reference Cresti1986: 318). Instead, Ciocchetti filled with images every parapet, pier, architrave and wall, and relied on a more evocative iconological programme, in which Fascist aesthetics echoed a revived romanità in order to cultivate national identity (Olariu, Reference Olariu2012; Parodo, Reference Parodo2016). An important educational role was played by the Mostra Augustea and even by the architect-designed sets for blockbuster films such as Scipione l'Africano (1937) (Fig. 16, bottom). The designer of the latter, Pietro Aschieri (Reference Aschieri1937), claimed that ‘Rome's architectural and stylistic character cannot be expressed through simple and naked sets, in which the scenographical character relies exclusively on the interplay of volumes … Roman architecture is most of all characterized by elements of detail’ and concluded that the architect-scenographer should express his creativity and fantasy ‘to satisfy the audience's emotional and sensational needs’.

Fig. 16. Top: the tribune in via dell'Impero on the Third Anniversary of the Foundation of the Empire (9 May 1939); bottom: set of Scipione l'Africano (1937) (both author's collection).

The interaction between spectators and urban context was a crucial aspect of the military parades of 1938–9, in which the presence of Ciocchetti's tribune altered the normal status of via dei Trionfi and via dell'Impero, and alerted the viewer to its double function of actor–spectator within an inclusive show. Dealing with the ‘architecture of the ceremonies’, art critic Agnoldomenico Pica (Reference Pica, Rava, Ulrich and Vaj1942: 23, see also 18–21) claimed that ‘the essence of celebrative architecture must be given by the crowd itself’ and observed that, in the central area of a city,

the issue is not just to create a tight unitary whole but to overlay it to a background that is often unfit and rebel to any rhythm, with the practical, and moreover also aesthetical, impossibility to conceal the surrounding buildings completely … in this case, the temporary elements should have such an authority to become the focus of attention and create the new environment in an illusionistic way.

The expressive freedom allowed by the insubstantiality of the materials and by the temporary nature of the structures made

the largest environment — a great theatre, a street, a square, an entire city — quiver in unison with the crowd in the heroic, or glorious, or religious atmosphere of one hour. The goal is that, for a very short lapse of time, a city, a square, an urban environment may change their appearance and strip themselves of almost any contingent and realistic connection to turn into a pure concert of rhythms, into pure volumetric abstraction, into an enthusiastic set of forms and colours.

The combination of ephemeral architecture and festival created a test space and a sense of belonging to the community by means of images already present in the collective memory.

After 9 May 1938 the temporary structures erected in Rome disappeared except for the Ostiense station, which was replaced by the building we see today, designed by the same architect of the ephemeral version. Instead, Ciocchetti's tribune reappeared one year later in what should have been its original location, via dell'Impero; apparently its pieces had been carefully numbered and stored, and then reassembled for more than one month (9 May–10 June 1939), which makes it less ephemeral than originally assumed. The ‘new’ tribune stood next to the statue of Julius Caesar that Ciocchetti had replicated twice in marble, and in front of the copy of the Augustus from Prima Porta (without Cupid and dolphin), opposite the temple of Mars Ultor. Its reappearance exalted the pre-existing cityscape and manipulated the memory of the site, since it belonged to Rome's recent history, too, and brought to mind the parade of 6 May 1938. The monumental centre of Rome was transformed once again thanks to this ephemeral, reversible and itinerant architecture.

On 26 March 1939, in a speech given on the twentieth anniversary of the Fascist Party, Mussolini claimed that any attempts to unhinge and bend the Rome–Berlin Axis were childish, and concluded: ‘We must arm. The word of command is this: more guns, more ships, more aeroplanes, at all costs and with every means’ (‘Signor Mussolini's speech on Sunday, March 26’, Bulletin of International News 16 (6 April 1939), 15–17). His statement seems to announce the reconstruction of the tribune and is consistent not only with the presence of the Nazi flags (see Fig. 16, top) but also with the four reliefs of the armed forces. The tribune was rebuilt in less than three weeks because on 21 April 1939, during the parade of the GIL, the pavement of via dell'Impero was still free. It was first reused on 9 May 1939, precisely one year after Hitler's departure from Italy, on the Third Anniversary of the Foundation of the Empire, which was associated with the festival of the retired army officers and the celebration of the soldiers fallen for Spain (Fig. 16, top).Footnote 38 On that occasion, the reliefs could be related to the successful military campaign of April 1939 in Albania, too: the map of the Fascist empire had just been updated and the Albanian troops paraded along via dell'Impero. In its new version, the parapets of the bays closer to the central sector were aligned with the piers of the side wings (Fig. 16, top) and the rear doorways were accessible by means of staircases from the car park behind.Footnote 39 The second event involving the tribune, scheduled on 28 May 1939 (six days after the Pact of Steel), was a parade of 70,000 Fascist women wearing military uniforms and shouldering miniature rifles (Fig. 17).Footnote 40 A newspaper (La Donna Fascista 21 (15 May 1939)) claimed that ‘the brides and mothers of the legionaries of the Empire are worthy, in the Roman way, of the tasks entrusted to them by the Revolution’. The king-emperor was absent, the Blackshirts replaced the Corazzieri, and a drapery with three fasces covered the Savoia coat of arms. Mussolini ‘appropriated’ the tribune and stood at the edge of the podium, where a platform flanked by flower beds materialized the arengario of the Palazzo del Littorio. L'Illustrazione Italiana 23 (4 June 1939) published his picture on the cover, next to the advertisement of ‘Caesar. The elegant clothes for the elegant man’, which depicts a female hand grasping four cards with Julius Caesar's portrait (Fig. 18). If the Fascist women looked like modern Amazons, Il Duce was a sort of statue similar to those of the Roman emperors displayed along the road; indeed, in the late 1930s Mussolini promoted ‘the petrification of his own image … turning it into a living statue’ (Gentile, Reference Gentile2007: 131–4).Footnote 41 The photos of the parade show the exchange of gazes between Il Duce and the Fascist women, who marched ‘fixing their eyes in his eyes’ and seemed to approach the Victory and her followers as they would an actual group of legionaries encountered on via dell'Impero (cf. Fig. 17, bottom); the goddess, with her feminine curves, represented an almost gentle militarism that contrasted with the martial atmosphere. The third and last event in which the royal-imperial tribune appeared along via dell'Impero, the First Festival of the Royal Navy, took place on 10 June 1939 (Fig. 19): the procession moved from Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum — note that the first stretch of the via Imperiale heading from Rome toward the E42 and the Tyrrhenian Sea had just been inaugurated — and recreated the same flow as the parade of 6 May 1938 (Fig. 20).Footnote 42

Fig. 17. Mussolini on the tribune during the parade of the Fascist women in via dell'Impero (28 May 1939) (both author's collection).

Fig. 18. Left: advertisement for the brand CAESAR (opposite the cover). Right: Mussolini standing on the tribune during the parade of the Fascist women in via dell'Impero (28 May 1939) (cover of L'Illustrazione Italiana 23 (4 June 1939)).

Fig. 19. The tribune in via dell'Impero on the First Festival of the Royal Navy (10 June 1939) (author's collection).

Fig. 20. Top: the tribune in via dei Trionfi during the parade of 6 May 1938; bottom: the tribune in via dell'Impero on the First Festival of the Royal Navy (10 June 1939) (both author's collection).

Three months later Germany invaded Poland and the winds of war marked the end of a tribune that had been designed from the outset as a monument to victorious war. Indeed, on 9 May 1940 it was not reassembled for the Fourth Anniversary of the Foundation of the Empire, when Mussolini gave a short speech from the balcony of Palazzo Venezia (L'Illustrazione Italiana 19 (12 May 1940)). On 10 June he declared war upon France and the United Kingdom. After World War II the cult of romanità was regarded as a picturesque and pathetic aspect of the Fascist regime: the legionary standards and the lictor's fasces became the symbols of an insanity that led to a collective disaster. The royal-imperial tribune disappeared from the scene like the marble map of the Fascist empire. Today its photos in Rome's monumental centre look like photomontages but in the late 1930s that ephemeral building forged powerful connections between romanità and Fascism by serving the self-celebration of a totalitarian regime, which may explain its eventual damnatio memoriae. The history of post-World War II Italy is characterized by the erasure of almost all the sculptural symbols of the Fascist regime, but with few exceptions the total demolition of buildings was carefully avoided. In the case of our ephemeral structure the damnation of memory does not refer to, say, the use of a pickaxe due to its association with the Savoia or with Hitler and Mussolini: we do not even know whether the tribune was accidentally or intentionally destroyed and it cannot even be excluded that some of its decorative elements still survive in the storerooms of the Genio Militare. Ciocchetti's tribune has simply been purged from modern memory also because, unfortunately, some architectural historians still consider such temporary structures to be unexceptional, bland, ordinary and banal, except for the most visible ones (e.g. the temporary façades of the Palazzo delle Esposizioni for the exhibitions of the 1930s). This indifference simply confirms the suggestion that Fascist ephemeral architecture deserves further examination. Despite the references to ancient Rome and the Savoia, architecture and sculpture combined in our royal-imperial tribune to glorify the armed forces, foster a national identity and create a common memory, precisely like Ciocchetti's monuments to the fallen soldiers. However, the power of the myth of Rome, the Savoia dynasty and the Italian army proved to be as ephemeral as the tribune, which was the expression of a totalitarian and militaristic regime that aimed at eternity and permanence by spreading a new secular religion (Gentile, Reference Gentile1993).

CONCLUSIONS

Architects and architectural historians have long seen permanent constructions as more significant and central to architecture than ephemeral works. Yet, the latter can be considered to be the very origin of architecture. In imperial Rome, for example, temples and spectacle buildings were stone versions of their wooden predecessors. Leaving aside the pons Sublicius, the preservation of which was a matter of religion, wooden theatres and amphitheatres were brought into existence in their usual locations for a short lapse of time and only at the end of the Republican age and in the first century AD, respectively, were replaced by permanent buildings. Other ephemeral structures appeared in ceremonies of imperial apotheosis, when monumental funerary pyres were erected in the Campus Martius (D'Ambra, Reference D'Ambra, Ewald and Noreña2010), and for other events. Archaeological evidence suggests the existence of wooden barrel vaults in the Forum of Augustus and in the Temple of Peace where, however, the actual structure was not made clear to the viewer. Temporary architecture in the papal city was often reserved for religious processions and celebrative events. The goal of ‘festival architecture’ was to amuse the spectators by means of illusion and amazement. Among the countless ephemeral buildings dating from the Renaissance up to the Capture of Rome in 1870, suffice it to mention the Capitoline theatre (1513) (D'Onofrio, Reference D'Onofrio1973: 129–36) or the circus erected next to Ponte Milvio for Pope Pius IX's return to Rome (1857) (Carnevalini, Reference Carnevalini1858).

The success of ephemera, fuelled by the sparkling atmosphere of the temporary pavilions built for the World Fairs since the nineteenth century, found a fertile soil in Mussolini's Rome, where many exhibitions were organized throughout the Ventennio. The celebrative opportunities for self-representation of the Fascist regime made it possible to create great sets that altered the urban space for long periods, such as the ephemeral façades of the Palazzo delle Esposizioni for the exhibitions of 1932–4 and 1937–8, or the pavilions erected in the Circus Maximus in 1937–9 (with a coda in 1940). In these events the goal was not only marvel but also persuasion: the ephemeral architectures transmitted messages of propaganda to the crowds and served the self-representation of Fascism's political authority. Yet, a sector of design potentially open to fantasy and invention became too often a reiteration of Roman building types and Fascist symbols: with a few exceptions (e.g. the ‘Living Arch’ in Naples), Fascist ephemera lacked originality, if compared with the spectacular effects and ingenious artistry of the Baroque period.