Introduction

In 1976, Jewson demonstrated in a paper entitled “The Disappearance of the Sick-Man from Medical Cosmology” (Jewson, Reference Jewson1976) that the production of medical knowledge shifted between 1770 and 1870 from the sick toward medical investigation and from the whole person toward a fragmented perspective. Indeed, prior to the anatomical–pathological method, physicians relied on symptoms, identified through the patient's discourse, as illustrated by the epistolary heritage of Tissot, who treated patients throughout Europe based on correspondence (Barras and Louis-Courvoisier, Reference Barras and Louis-Courvoisier2001); patient or significant others detailed in letters the bodily experiences and Tissot provided advice. Patient's subjectivity was thus key to orient the physician.

The anatomical–pathological turn, attributed to Bichat (Shoja et al., Reference Shoja, Tubbs and Loukas2008), revolutionized medicine by linking lesions observed in autopsies to symptoms experienced by the diseased. The medical gaze (Foucault, Reference Foucault1973) thus started its successful journey, later replaced by more and more sophisticated methods to “look into the body” like analyses of fluids, biomedical imaging, or molecular biology. These techniques allowed considerable progress, but also diminished the relevance of the subjective experience of the sick man.

The psychosomatic movement (Wittkower, Reference Wittkower1974), raising after World War II, and the subsequent bio-psycho-social model introduced by Engel (Reference Engel1977) aimed to rehabilitate the patient as a whole person. However, the biomedical model still prevails, despite recent efforts to promote patient-centeredness, empowerment and shared decision-making (Epstein and Street, Reference Epstein and Street2011).

Symptom descriptions remain important to diagnose diseases, but also to understand illness representations and associated behaviors, and symptoms provide cues for engaging in an empathic relationship and to strengthen therapeutic alliance (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ferreira and Maher2010).

Beside the documentation and quantification of symptoms (Bruera et al., Reference Bruera, Kuehn and Miller1991; Tranmer et al., Reference Tranmer, Heyland and Dudgeon2003; Kirkova et al., Reference Kirkova, Davis and Walsh2006; Trajkovic-Vidakovic et al., Reference Trajkovic-Vidakovic, de Graeff and Voest2012), researchers investigated symptom distress and experience (Akin et al., Reference Akin, Can and Aydiner2010; Molassiotis et al., Reference Molassiotis, Zheng and Denton-Cardew2010), symptom attributions, meaning and beliefs (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Wiese and Moore1981; Richer and Ezer, Reference Richer and Ezer2000; Heidrich et al., Reference Heidrich, Egan and Hengudomsub2006; Estacio et al., Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2017, Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2018), situational and existential meaning of symptoms (Richer and Ezer, Reference Richer and Ezer2000; Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2003), symptom burden (Doumit et al., Reference Doumit, Huijer and Kelley2007), and symptom familiarity (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Wiese and Moore1981). In addition, socio-anthropologists and phenomenologists identified cultural, educational, social, and economic determinants of symptom experience (Kirmayer et al., Reference Kirmayer, Young and Robbins1994; Lobchuk and Stymeist, Reference Lobchuk and Stymeist1999; Bell, Reference Bell2009).

Studies assessing how symptoms circulate in real-world conditions are rare and mainly conducted in patient populations representing major challenges to clinicians like those with medically unexplained symptoms (Ring et al., Reference Ring, Dowrick and Humphris2005; Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Ring and Dowrick2005; Stortenbeker et al., Reference Stortenbeker, Stommel and van Dulmen2020). These studies demonstrate that physicians rarely respond to suffering and misinterpret what patients expect from them (e.g., medical investigations according to physicians and empathy according to observers) (Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Ring and Dowrick2005). With regard to studies of medical consultations, Beach et al. (Reference Beach, Easter and Good2005) observed in video excerpts that physicians exhibit minimal receptiveness to patients’ lifeworld disclosures (e.g., they redirect attention to their medical agenda). Estacio et al. (Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2017) found that in palliative care consultations, the main response to patient's symptom presentation — independent of the symptom meaning — was medical. Others observed that physicians show difficulties to identify informational and emotional cues conveyed by symptoms (Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Del Piccolo and Finset2007) when giving patients explanations for their symptoms (van Ravenzwaaij et al., Reference van Ravenzwaaij, Olde Hartman and Van Ravesteijn2010).

Against this background, the present study aimed to comprehend how symptoms circulate in the medical encounter, how they emerge, disappear, and sometimes re-emerge, what they convey, which functions they fulfill, and how physicians respond to them. In other words, the goal was to situate patient's symptoms by examining them inductively in real-world conditions.

Methods

Material

The material is part of a dataset consisting of 134 consultations of 24 oncology physicians with 134 patients with advanced cancer, audiotaped, and transcribed verbatim for a naturalistic multicenter observational study (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Gholamrezaee and Verdonck-de Leeuw2017); the study received approval by the ethics committee of the participating hospitals, and patients signed an informed consent form. Patients knew that they have advanced cancer and that they receive palliative treatment. The objective of the consultations was to discuss results of investigations (e.g., CT scans and tumor marker levels) documenting disease evolution.

Five consultations were purposively selected based on a previous identification of specific symptom discussions.

Data analysis

Based on the empirical literature (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Wiese and Moore1981; Beach et al., Reference Beach, Easter and Good2005; Ring et al., Reference Ring, Dowrick and Humphris2005; Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Ring and Dowrick2005; Doumit et al., Reference Doumit, Huijer and Kelley2007; Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Del Piccolo and Finset2007; Akin et al., Reference Akin, Can and Aydiner2010; van Ravenzwaaij et al., Reference van Ravenzwaaij, Olde Hartman and Van Ravesteijn2010; Estacio et al., Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2017, Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2018; Stortenbeker et al., Reference Stortenbeker, Stommel and van Dulmen2020), we developed a framework for the analysis, which provided “sensitizing concepts” (Bowen, Reference Bowen2006). These concepts suggested “directions along which to look without prescribing what to see” (Bowen, Reference Bowen2006; Bombeke et al., Reference Bombeke, Symons and Vermeire2012). The analysis consisted of iterative reading to gain a comprehensive view, coding, and group discussions to obtain a fine-grained understanding of the symptom dimensions. We adopted a multiple case study approach, which allows in-depth contextual explorations of complex issues (Crowe et al., Reference Crowe, Cresswell and Robertson2011).

In the results section, the four consultations are shorten in a way to both keep the flow of interaction between the patient and the oncologist, and to account for the consultation content around and beyond symptom discussions. The speech turns to which we refer in the following are numbered in square brackets, which relate to Tables 1–5 (transcripts).

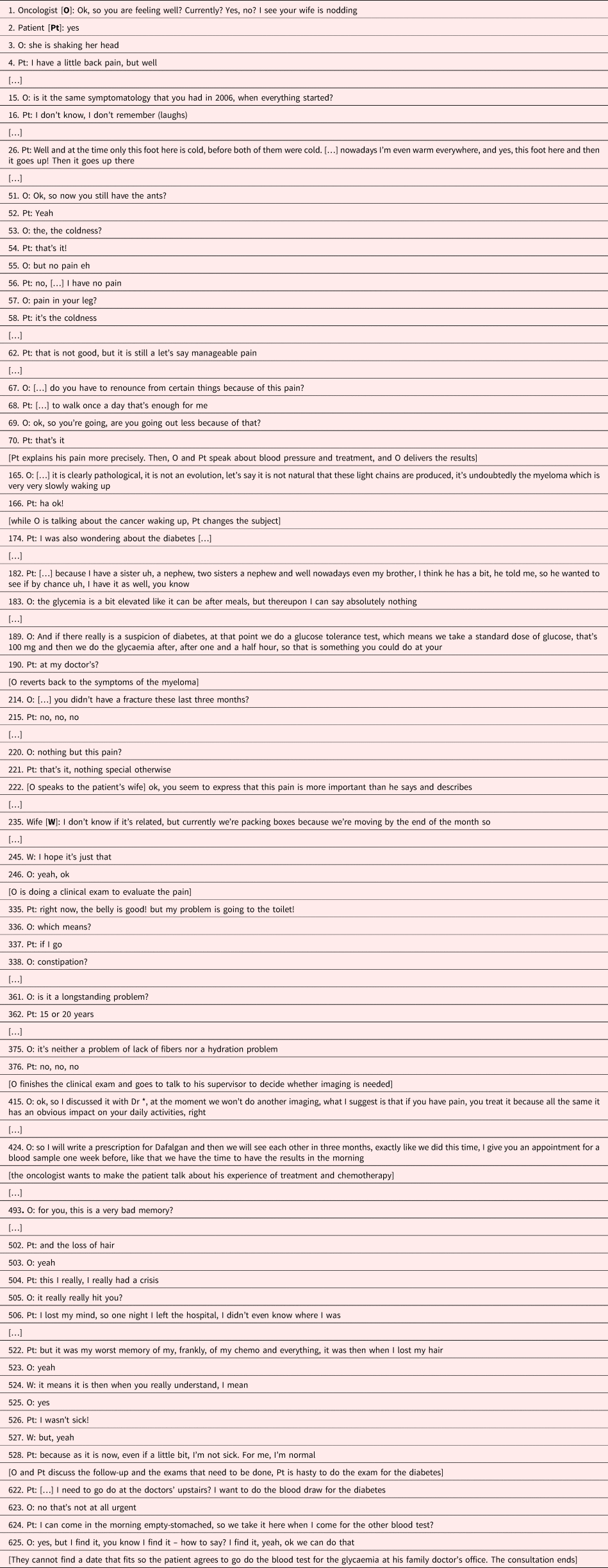

Table 1. Case 1: A dialogue of the deaf

Table 2. Case 2: Who needs reassurance

Table 3. Case 3: Symptoms as protection

Table 4. Case 4: Iatrogenic symptom persistence

Table 5. Case 5: The total symptomatic body

Results

Case 1: A dialogue of the deaf

What strikes first is that the patient calls his symptom “belt” (“I have a belt here inside of me”) [14] (see Table 1), which illustrates that patients describe symptoms based on their lay representations (Stiefel, Reference Stiefel1993), and that symptoms are situated in the lived experience of the body (Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, Widmark and Rasmussen2006). In this experience, emotions and not only (cognitive) representations, influencing each other, play an important role (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Fallowfield and Lewis1996). Here, the symptoms may be associated with shame, since the patient links it to the possible existence of hemorrhoids [32–35]. The symptom seems most relevant, and the patient repeatedly evokes it throughout the consultation [14, 88, 118, 206, 346]. For cancer patients, new symptoms are first of all related to cancer (Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, Widmark and Rasmussen2006), unless a less threatening explanation is found. In this case, the symptom seems not threatening, but shameful.

The other symptom, related to his knee [304–307], carries a specific significance for the patient, who seems not to understand that it is not a priority to operate his knee (given the limited life expectancy). It could also be that the symptom is introduced as a non-threatening topic, or — if an operation is proposed — a mean to gain hope for a certain life expectancy. If this latter is the case, the presentation of this symptom is a displacement, expressing psychological needs, which require clarification and an adequate response.

The physician focuses on symptoms, which are signs of cancer progression [159] or serious medical problems (coughing and trouble to breath) [49–53]. With regard to the “belt” symptom, the oncologist remains vague [35, 39, 101, 209, 213, 345] and avoids to address an issue of which he cannot make any sense. Concerning the complaints about the knee, the physician answers indirectly (“I don't think they will operate on you”) [307]. An alternative would be to acknowledge that one does not know the origins of this symptom or to discuss the limited life expectancy.

A lack of dialog is observable with a physician asking for symptoms the patient does not have [49–53], and a patient evoking symptoms, which remain unheard, and thus repeatedly re-emerge during the consultation. Moreover, associated shame, burden (“belt”) or limited life expectancy (knee) remain unaddressed.

Previous research demonstrated that oncologists focus on the biomedical (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Fallowfield and Lewis1996). In this consultation, the physician links symptoms to clinical and para-clinical investigations [101–143]. Consequently, the “invisibility” of the “belt” symptom obscures its existence, motivating the patient to ask for an investigation (colonoscopy) [173], which may render it more visible, existent, and addressable. Finally, medical rationality dominates, since the physician decides which symptoms are relevant or not and associated representations, emotions, concerns, and psychological functions await to be addressed (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Easter and Good2005). Consequently, time is wasted and opportunities to strengthen therapeutic alliance — at the core of situations with limited medical power — are missed.

Case 2: Who needs reassurance?

This consultation raises the issue of how to reassure — if necessary — when a symptoms of somatic or psychic origin emerge (see Table 2). Patients are expected to report their symptoms and physicians to respond. Symptoms thus connect patients and physicians, their lay and biomedical frameworks, however, separate them (Gibbins et al., Reference Gibbins, Bhatia and Forbes2014; Estacio et al, Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2018).

It is widely accepted that pain is subjective, may exist in the absence of tissue damage, or has a psychological origin (Loeser and Treede, Reference Loeser and Treede2008). In this consultation, the patient reports pain in her chest, hips, and pelvis [118, 227]. The oncologist insists that the pain is not tumor-related, based on its location [206–222, 230] (the scanner showed no lesions that could explain the pain, and the tumor itself is not supposed to hurt …), and provides alternative explanations (scars or sequela of chemotherapy) [198, 222]. We do not known whether the patient believes that the tumor hurts or whether she simply reports every symptoms assuming the patient role, as has been observed in cancer patients (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Easter and Good2005; Estacio et al., Reference Estacio, Butow and Lovell2017). The physician does not consider the symptoms as dangerous, or at least not caused by the cancer, and repeatedly states that there is nothing to worry about [206, 214, 220, 222, 280]. She appears to believe that the patient fears the symptom and links it to cancer — this is indeed often, but not always the case — but she does not explore if this is really the case. Either the oncologist fears that the patient fears the symptoms and attempts to reassure her, or reassures herself by repeatedly stating that the symptom is not cancer-related, or she is contaminated by the patient's anxiety. While physicians usually aim to transform the patient's situation into a clinical situation, here the circulating emotions triggered by symptom expression transform the clinical situation into a psychological situation, marked by anxiety-induced avoidance.

Sometimes, patients use complementary treatments (Ben-Arye et al., Reference Ben-Arye, Bar-Sela and Frenkel2006), as in this consultation, in which the intake of baking soda is discussed [363]. The patient hereby not only reveals her illness representations, she also demonstrates active coping (Weisman and Sobel, Reference Weisman and Sobel1979), which has a (self-)reassuring function. Baking soda can be considered as a third party object — complementary medicine — which may indicate reluctance to delegate responsibility for treatment solely to the physician. By ignoring the psychological aspects of baking soda [370–428], the clinician misses an opportunity to explore and validate the patient's coping strategies or to address her potential lack of trust.

Finally, this consultation also illustrates the differences between physical and psychological symptoms. While somatic symptoms call for a medical response, psychological symptoms need expression, clarification, understanding, and if pathological, orientation toward specific treatment. At the end of the consultation, the oncologist tries again to reassure the patient, but this time with regard to feelings of guilt [463–464]. The underlying motive of guilt, however, remains unexplored. A possible explanation lies in an often-observed desire of clinicians to “solve patients’ problems,” which — when this seems impossible — provokes premature and inadequate reassurance or downplaying of the patient's experiences (Stiefel, Reference Stiefel2006). Here, the oncologist does not explore the patients’ feelings of guilt, but attempts to reassure by communicating that she suffers and should not feel guilty of feeling fine, and that if she does not suffer much, it is because she is very brave [464].

One might ask what this reassuring stance, which runs like a red string throughout the consultation, signifies. Do the attempts to reassure have the intended effect or do they increase the patient's uneasiness? Indeed, since they lack exploration and understanding, they could decrease the patient's feeling of isolation (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Easter and Good2005). In other word, the oncologist's attempts to reassure may respond to her own psychological needs. Here, the clinician turns a clinical situation — from a psychological point of view — into a non-therapeutic situation.

Case 3: Symptoms as protection

In presence of a third party, such as in this consultation with a member of the family, the probability that a symptom is reported increases (see Table 3). For reasons such as forgetting to tell, not to bother the physician, shame, or fear that treatment would be reduced, patients may indeed silence or minimize symptoms (Lindley et al., Reference Lindley, McCune and Thomason1999) [4]. Here, it is the wife, who reports the symptom and specifies its intensity, which seems to be higher than the patient indicates [222]. Intensity alone does not determine symptom experience, which depends also on its frequency, associated distress, attributed meaning, and disruptive effects (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong2003; Gill et al., Reference Gill, Chakraborty and Selby2012). The wife and the patient attribute a different meaning to the symptom. The wife fears it to be cancer-related and hopes it to be mobility-related, (“I hope it's just that”) [245], and the patient is not worried (“As it is now, even if a little bit, I'm not sick. For me, I'm normal”) [528]). The patient renounces to elaborate on the symptom, and it remains unclear if — in the constant cycle of feeling ill and feeling well (Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, Widmark and Rasmussen2006) — he is truly feeling well.

There are nowadays many ways to monitor diseases, as illustrated here by the references to the light chains [165]. Even when patients are reluctant to talk about a symptom and/or down play it, the physician can thus rely on a laboratory or imaging data. The patient's shifting the discussion to diabetes [174, 182] may indicate that he actually links the back pain to increased disease activity, and thus displaces the attention to another, less threatening topic (see also Case 1). A clue for displacement is that the patient expresses almost no concerns with regard to the myeloma.

The oncologist probably reacts (unconsciously) to the patients’ displacement and stops to focus on the disease, but introduces as a new topic the last treatment and the next chemotherapy. Paradoxically, this shift provokes the remembrance of a symptom, which has a specific significance, feared by the patient: hair loss [493–522]. Hair loss materializes the disease, designates the patient as a cancer patient, and exposes him to the gaze of others. In addition, hair loss can provoke loss of self-esteem and trauma, and modifies social interactions (Rosman, Reference Rosman2004). Here, discussion of hair loss temporarily breaks the patient's down playing of the disease and/or its severity [524–528]. Hair loss also illustrates the symbolic aspects of symptoms, carrying individual meaning, linked to biography and collective meaning, as hair loss is associated with old age and disease, especially cancer, but also with stigma and punishment (Hansen, Reference Hansen2007).

Finally, the tendency of the patient to down play his disease might be facilitated by the fact that myeloma, unlike solid tumors, have a hidden and ubiquitous localization and might thus create more anxiety (and denial) (Ernst et al., Reference Ernst, Kuhnt and Schwarzer2011) [528].

Case 4: Iatrogenic symptom persistence

In this consultation, the patient clearly favors complementary over biomedical treatments [110, 354, 401] (see Table 4), which can be an indicator for mistrust, anger, deception, anxiety, a desire not to put all eggs in one basket or of certain representation and belief system. Consequently, this stance should be explored from a cognitive-representational, emotional, and interactional perspective, especially when treatment side effects or iatrogenic symptoms bother the patient. Depending on motivations, answers differ and are not limited to warn about possible interferences of complementary approaches with oncological treatments [111].

The consultation also illustrates that patients consider their symptoms diachronically: when treatments end, side effects are also expected to end (Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Hansen and Moskowitz2010; Wu and Harden, Reference Wu and Harden2015). This patient has either not been informed or has not retained the information, and the oncologist has thus to confront her with the possibility that side effects persist for some time or even become chronic [133, 135, 468].

In oncology, iatrogenic symptoms are the price to pay for treatment benefices. To put it differently, the end justifies the means. However, iatrogenic symptoms may provoke anger or deception, especially if treatment is not effective or, as here, the patient did not anticipate that they persist [134, 465–469, 473, 578, 580]. On the other hand, the oncologist may feel guilty, especially when side effects surpass benefits of treatment. Furthermore, having to choose — to decide upon “the price to pay” — puts pressure on the patient–physician relationship [133–136, 142–143]. However, reducing the dose of chemotherapy in view of side effects can also provoke fears, and decreased side effects may be interpreted that treatment is not effective (Bell, Reference Bell2009). This illustrates that — exceptionally — symptoms may also have positive meanings for patients (Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann, Del Piccolo and Finset2007).

The physician's statement that the abdomen is very supple [309] seems not to be as relevant for the patient as it is for the physician; it might be comfortable for the physician to discuss good news, and to provide explanations [321], illustrating that things are under control. It might not be pure chance that this statement comes right after delivering the bad news that there might be persisting side effects (which surprises the patient). For some patients — as for some physicians — explanations may be helpful, but they do not make symptoms disappear (Ream and Richardson, Reference Ream and Richardson1996). Addressing eventual feelings of deception or understandable anger over side effects might thus be more beneficial.

Another striking element is that the physician repeats the information about persisting side effects several times [5, 129, 133, 135, 470, 547, 553, 579], but never asks if the patient understands. A clue, that the patient might not have understood why and how side effect persist, is the analogy she makes with her sleep (“it will get better and better”) [473]. Later, in the consultation, the oncologist again addresses the absence of certain symptoms [509], probably to reassure the patient or to convey that she has been spared of other symptoms. Does this kind of consolation reassure the oncologist or the patient? Again, is it pure chance that such explanations are provided, while handicapping and persisting side effects exist [553], which might be difficult to bear [465]? Are these explanations an expression of the oncologist's anxiety or guilt?

Finally, we see that when a third party — here a third party welcomed by the oncologist — has to solve medical problems [the skin problem (makeup)], the oncologist overhears the associated difficulties expressed by the patient. The physician evacuates the problem by delegating it to the third party, even if this third party does not seem to be of much use [612–621]. As for patients, physicians’ introduction of a third party (e.g., another specialist, psychologist, or chaplain) has various motivations, among them are negative counter-attitudes (Tzartzas et al., Reference Tzartzas, Oberhauser and Marion-Veyron2019).

In this consultation, the clinical situation is overshadowed by the relational situation, which is under pressure by third-party elements and persisting side effects.

Case 5: A total symptomatic body

Acute symptoms indicate a disorder and orient care (see Table 5). In this consultation, we observe a cacophony of symptoms; one could speak of a total symptomatic body in analogy with total pain (Clark, Reference Clark1999), which hampers the orientation of care. Despite the fact that multiple symptoms are frequent and provoke other experiences than single symptoms, studies are most often limited to clustering symptoms and examine the patient perspective (Mehta and Chan, Reference Mehta and Chan2008). Here, symptoms are caused by the disease and co-exist with iatrogenic and psychological symptoms [7, 102, 148–149, 479, 482, 791].

The patient seems to endure a traumatic experience, which reduces her discourse to a testimony of repetitive grievances. The medical response can thus not be limited to the evaluation of each symptom and the prescription of an antidepressant, but has to address the trauma and existential suffering.

The question is how to care for this multi-symptomatic patient? We are here beyond disease expression, beyond psychosocial consequences or determinants of symptoms, and beyond symbolic meaning. The existential dimension of the symptoms requires acknowledgement that the patient suffers and that her state is unbearable (Le Breton, Reference Le Breton2006). Such an intervention — even if this will not reduce symptom burden — would allow the patient to feel understood and reduce her loneliness (Beach et al., Reference Beach, Easter and Good2005). A supportive response, consisting of a statement that the physician is affected by the patient's suffering, recognizing his own impotence and inability to help, would here also show the family, who has turned their own impotence into an aggressive denial of the patient's distress, an example of an alternative stance [467–473, 749–794, 803–811]. The mere mention of an antidepressant, on the other hand, may convey that the patient's suffering is due to a psychiatric condition, and may be understood by the patient that the physician, like the family, wishes to silence her [774–794].

Discussion

This case series revealed that symptoms are situated in a socio-historical context, anchored in the patient's lived experience, loaded with psychosocial elements, and possess interactional and communicative purposes.

We identified seven main and often interwoven symptom dimensions. The cognitive dimensions relate to representations and attributions, influenced by a variety of factors like the origins of the symptoms (disease and side effects/iatrogenic), associated emotions, medical and lay information, or experiences with one's own or others’ diseases. The emotional dimensions play a role with regard to symptom intensity (for example, by amplified anxiety) and symptom expression — shame or guilt may deny or downplay a symptom. The psychological dimensions orient and distract the clinician's attention (e.g., to unthreatening symptoms in case of displacement), and influence symptom perception and expression. The interactional dimensions, operating in symptoms conveying distress, explore the clinician's views (e.g., with regard to survival) or express anger (e.g., over iatrogenic symptoms). The inverse may also take place, with patients, who wish “to protect” the physician by denying symptoms. The symbolic dimensions encompass signs with an individual or collective meaning, such as hair loss. The experiential dimensions refer to symptoms, which alter how the patient “relates to, moves in and is affected by the world” and restrict his/her world (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein1995). The existential dimension as appearing in a total symptomatic body may cut patients from others and the world, throwing them into an unbearable state of isolation.

Physicians, on the other hand, receive the symptom not in a neutral, unaffected, rational and scientific way. Perception differs, if the symptom is related to cancer (or not), understood (or not), caused by the disease or treatment, useful (or not) to monitor disease, and with somatic or psychic origin. Physicians’ capacity to contain suffering and to tolerate uncertainty and impotence will determine how they deal with a symptom, as does the individual medical approach (e.g., more or less patient-centered).

Symptoms allow interaction. However, a symptom may also become the joint focus of the patient and the physician to avoid the bigger picture, namely the progression of disease and its consequences. Symptoms are thus not only a mean to diagnose, but also require themselves a diagnosis. Before providing a therapeutic response, the physician has to “diagnose” and understand the significance of the symptom, since his/her response differs depending on the aforementioned dimensions involved in the symptom production. For example, information may respond to the cognitive dimensions, empathy to emotional dimensions, understanding to psychological dimensions, relationship building to interactional dimensions, verbalization to symbolic dimensions, interest for the daily living to experiential dimensions, and capacity to contain to existential dimensions.

The fundamental challenge for the physician is the symptom's subjectivity, not only with regard to its impact — this has been repeatedly underlined in the medical, especially the palliative care literature — but in the sense of the other in his/her otherness. This case series illustrates that a lack of effort from the physician to explore different symptom dimensions may hamper understanding, and turn the symptom, which should unify the patient and the clinician, into an obstacle of their encounter, provoking misunderstandings and deceptions. On the other hand, when the different symptom dimensions are explored, symptoms become a bridge between the patient and the physician.

This case series illustrates that the art of medicine is to turn a situation into a clinical situation. The beauty of the clinical situation — and this is certainly one of the motivations to become a physician — is that a clinical situation is a cognitive, emotional, psychological, interactional, symbolic, experiential, and existential situation for both the patient and the physician.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material selection and data analysis were performed by C.B. and F.S.. The first draft of the manuscript was written by C.B.ourquin and F.S., and they commented on the different versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Annina Steller who contributed to some parts of this study.

Funding

This study was supported by Swiss Cancer Research (grant no. KFS-3459-08-2014).

Conflict of interest

None declared.