INTRODUCTION

In recent years, palliative care research has focused on the concept of the demoralization syndrome, a term used to describe existential distress and despair in palliative care (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Clarke and Street2001). It has been proposed by some that the demoralization syndrome be recognized as a psychiatric condition and included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Clarke and Street2001). Considerable debate has emerged in the literature on whether demoralization reflects a normal response to difficult circumstances in palliative care, is a form of depression, or constitutes a unique syndrome of despair, distress, and hopelessness separate from depression (Slavney, Reference Slavney1999; Parker, Reference Parker2004). As yet its diagnostic criteria have not been accepted into the new edition of the DSM. The differentiation of demoralization from depression is essential for the demoralization syndrome to be considered a new diagnostic condition and secure a place in the future psychiatric classification systems.

In support of their demoralization syndrome, Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) have developed a self-report measure, the Demoralization Scale, to identify demoralization in advanced cancer. The Demoralization Scale is a 24-item, 5-point response, self-report questionnaire. The reliability and validity of the new measure was explored in a sample of 100 patients with advanced cancer. The factor structure of the Demoralization Scale using principal component analysis yielded five factors that were identified as loss of meaning, dysphoria, disheartenment, helplessness, and sense of failure.

Establishing divergent validity between the constructs of demoralization and depression is a vital requirement of the Demoralization Scale. Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) reported that 7–14% of the demoralized patients were not depressed. On the basis of these reported percentages, the authors concluded that divergent validity had been observed and the Demoralization Scale had shown that demoralization can be differentiated as a phenomenon distinct from depression warranting serious attention as a new diagnostic category in future classification systems.

On closer inspection, several inadequacies emerged in the interpretation of the data by Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004). The first issue relates to the reporting of the chi-square analysis used to determine the divergent validity of the Demoralization Scale. Kissane et al. reported that chi-square analysis was carried out to compare the high and low demoralization categories with the depression categories on the Patient Health Questionnaire and the Beck Depression Inventory. It was reported that 7–14% of patients were high in demoralization but not depressed. Other than reporting percentages, no statistical support for the divergence of demoralization and depression was presented. On the basis of percentages alone, Kissane et al.'s (2004) conclusions about divergent validity cannot be supported.

Moreover, although 14% of the sample were demoralized but not depressed, 85% of the depressed sample (n = 33) were demoralized. This supports evidence for the convergence and not the divergence of the two constructs. The interpretation of the data and the lack of sufficient information cast considerable doubt on the claim that divergent validity was achieved in the Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) validation study.

Another controversial issue that demands attention concerns the cutoff score used to determine those with high and low demoralization. A cutoff score for classifying patients with a high level and a low level of demoralization is necessary for research and clinical purposes. It is generally accepted as best practice that a cutoff for categorizing participants corresponds to one standard deviation above and below the mean.

In Kissane et al.'s (2004) study, the median score (30.82) was used to determine high and low demoralization categories. The high demoralization category corresponded to scores above the median (>30) and the low demoralization category included all those scoring below 30 on the Demoralization Scale. No rationale was presented in the paper to support the use of the median as a cutoff.

On the basis of the median cutoff, almost half (47%) of the sample were categorized as highly demoralized and half (53%) reported low demoralization. The median cutoff may have inflated the number classified as high in demoralization in the study. It would have been more accurate for Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) to use the accepted method of calculating cutoff scores (mean value ± one standard deviation).

It is premature to conclude that the divergent validity of the Demoralization Scale was demonstrated in the Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study. As the validation of the Demoralization Scale is of enormous importance, more research is required to establish the validity and reliability of the Demoralization Scale and explore its differentiation from depression.

The objective of the present study was a validation of the Demoralization Scale (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) in a sample of 100 Irish advanced cancer patients.

METHOD

Participants

One hundred inpatients with advanced cancer at St. Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin, were recruited to the study. A further 54 participants who consented to the study were excluded. Ten participants became confused and 44 did not complete the assessment battery, and these cases were not used because of large sections of missing data. Six eligible participants refused to take part, citing concerns regarding the potential risk of becoming psychologically distressed by the nature of the study.

Participants were excluded if they were deemed to be confused and too unwell for consent and interview as judged by the treating clinical team, unable to read English, or currently psychotic or had an intellectual disability.

Instruments

Demoralization Scale (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004)

The Demoralization Scale is a 24-item, 5-point response scale measuring demoralization. Respondents are asked to indicate how strongly each statement applied to them over the last 2 weeks. A 5-point response scale (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = all the time) described the frequency of occurrence of each item. Factor analysis using principal component analysis revealed a five-factor structure. High internal reliability was found with an alpha co-efficient of .94 for the total Demoralization Scale score. Convergent validity and divergent validity were reported (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004).

Beck Depression Inventory (2nd edition; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996)

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) consists of 21 self-report items that assess cognitive, affective, motivational, and vegetative symptoms of depression.

Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001)

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was developed as a self-report measure designed to assess the presence of DSM-IV criteria for major depressive episodes across a 2-week period.

Beck Hopelessness Scale (Beck & Steer, Reference Beck and Steer1988)

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) has been used in a wide variety of nonclinical and clinical populations.

Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death (Rosenfeld et al., Reference Rosenfeld, Breitbart and Galietta2000)

The Schedule of Attitudes towards Hastened Death (SAHD) is a 20-item self-report measure of desire for hastened death constructed in an HIV population and palliative cancer patients.

McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mount and Strobel1995)

The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL) is designed to measure quality of life for people with life-threatening illness in a palliative care population.

Hunter's Opinions and Personal Expectations Scale (Nunn et al., Reference Nunn, Lewin and Walton1996)

The Hunter's Opinions and Personal Expectations Scale (HOPES) is a 20-item self-report measure of personal hopefulness.

Procedure

Participants were administered the Demoralization Scale along with the six questionnaires. For the majority of participants (n = 76) the self-report questionnaires were read aloud. This change deviated from the procedure outlined in the Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study and was implemented as a result of participants tiring midway through the interview. The burden of completing seven questionnaires was noted for this palliative sample.

The study protocol received approval from the Ethics and Medical Research Committee, St. Vincent's Healthcare Group, St. Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Features

Forty-nine participants (49%) were male. The average age of participants was 64.26 years (SD = 11.56). Half (51%) of the participants were married, 22% were widowed, 16% were single, and 9% were separated or divorced. Eighty-three percent of the participants were Roman Catholic. Almost half of the participants were retired (49%). The most frequent primary tumors were colorectal (18%), lung (17%), genitourinary (16%), and breast (13%). All participants were in the advanced stages of their disease. The average length of cancer illness was 32.82 months (2.7 years; SD = 39.43).

Demoralization Scale Analysis

The mean total score on the Demoralization Scale for the 100 advanced cancer patients was 19.94 (SD = 14.62; range, 1–61; maximum possible score = 96). The present study sample was significantly less demoralized than the Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) sample, t(99) = −7.4, p < .05. When we used Cronbach's alpha, the overall internal consistency of the Demoralization Scale was high; the coefficient alpha was .93.

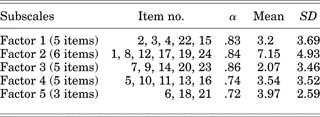

Factor Analysis

The primary aims of the current study were a validation of the Demoralization Scale using factor analysis and a comparison of the adequacy of Kissane et al.'s (2004) five-factor structure with the factors produced in the current study. Principal component analysis with a varimax rotation revealed five factors with eigenvalues of 9.483, 2.036, 1.704, 1.538, and 1.011. The percentage of variance explained by each of the five factors was 39.51%, 8.48%, 7.01%, 6.41%, and 4.21%, respectively, accounting for 65.72% of the total variance. Factor loadings are shown in Table 1. All five factors showed acceptable internal consistency, ranging from .72 to .86 as measured by Cronbach's alpha.

Table 1. Principal components analysis using Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization generating a five-factor solution after six iterations

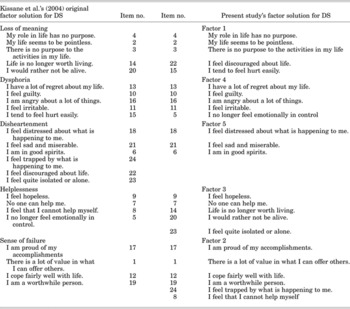

Table 2 compares the original five-factor solution (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) with the present study's factor structure. Overall, there is a high level of agreement observed between the five-factor solution proposed by Kissane and his colleagues and the five-factor solution emerging in the present study.

Table 2. Comparison of original Demoralization Scale (DS) five-factor solution with present study five-factor solution

However, although many commonalities among the two factor structures are observed, some differences are also evident. For example, the two items closest to suicidal ideation, “life is no longer worth living” and “I would rather not be alive,” both load onto the loss of meaning subscale in Kissane et al.'s (2004) factor structure but load onto Factor 3, which corresponds well with the Helplessness Factor from Kissane et al.'s (2004) study. On closer examination the Helplessness Factor and Factor 3 share only two items in common, and the current study's Factor 3 appears to be made up of items tapping into a Hopelessness Factor (“I feel hopeless”; “No one can help me”; “Life is no longer worth living”; “I would rather not be alive”; “I feel quite isolated or alone”).

Correlation analysis, using Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient and scattergram plots, was used to explore the relationship between the five-factor structure in Kissane et al.'s (2004) study and the new five factors in the current study. The new five-factor structure in the current study was similar to Kissane et al.'s (2004) factor solution. Correlations ranged from .799 to .957. Overall, the correlational analyses support the five-factor structure generated in Kissane et al.'s (2004) study.

Reliability and Validity

All five factors showed acceptable internal consistency, ranging from .72 to .86 as measured by Cronbach's alpha as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Reliability analyses for the five-factor solution derived from the Irish sample

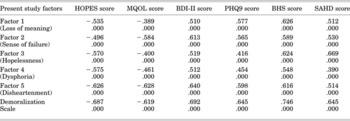

The concurrent validity of the present study's five-factor structure was explored using a Pearson's product moment correlation (Pearson's r) testing the relationship of the Demoralization Scale and the other measures assessed. The results of the analyses are indicated in Table 4. Strong correlations observed between the total score of the Demoralization Scale (DS) and depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death provides evidence that the Demoralization Scale has convergent validity.

Table 4. Pearson product moment correlation matrix (Pearson r Sig. (1-t)) of the Demoralization Scale five factors with the measures assessed

HOPES: Hunter's Opinions and Personal Expectations Scale; MQOL:McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale; SAHD: Schedule of Attitudes towards Hastened Death.

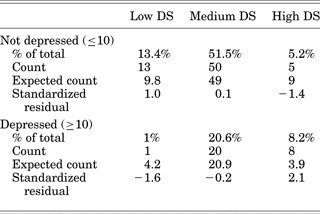

Establishing divergent validity between the constructs of demoralization and depression is essential for the validation of the Demoralization Scale. The most statistically sound way of determining the cutoff of a scale is to use the mean value ±1 standard deviation. Therefore, the Demoralization Scale was subdivided into three distinct categories based on a mean of 19.94 (SD = 14.62): low DS (≤5.33); medium DS (5.34–34.56), and high DS (≥34.57).

The demoralization data were compared with the PHQ-9 subcategories using chi-square analysis, and the results are presented in Table 5. The χ2 analysis found a significant relationship between PHQ-9 scores and DS categories, χ2(2, 97) = 9.73, p < .05. It can be observed from Table 5 that individuals with high demoralization were significantly more likely to be depressed and experience high levels of demoralization.

Table 5. Comparison of Patient Health Questionnaire depression scores (DS) with high, medium, and low demoralization cutoff scores

Similar analysis was conducted with the demoralization data and the subcategories of the Beck's Depression Inventory using chi-square analysis. The results are shown in Table 6. The chi-square analysis found a significant relationship between BDI-II scores and DS categories, χ2(6, 95) = 41.628, p < .05. The standardized residuals indicated that there were significantly fewer individuals in the high DS group and minimal BDI-II category than was expected due to chance and significantly more individuals in the low DS group and minimal depression category and significantly more individuals in the high DS and moderate and severely depressed groups than expected due to chance. Therefore, individuals with low demoralization were more likely to experience little depression and individuals with high demoralization were more likely to also report moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 6. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventory depression scores (DS) with high, medium, and low demoralization using cutoff scores

To understand Kissane et al.'s (2004) data more fully, their data were reanalyzed using chi-square analysis and standardized residuals. The chi-square analysis found that all cells departed significantly due to chance, χ2(1, 100) = 29.96, p < .05. The standard residuals showed that fewer participants were demoralized but not depressed and more depressed and demoralized than would have been expected due to chance. The results of the reanalysis of Kissane et al.'s (2004) data show the similarity between their data and the data reported in the current study. No evidence of divergent validity was found in their study and the current study using the median cutoff.

DISCUSSION

Principal component analysis of the Demoralization Scale yielded four factors similar to those found in Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study, namely, loss of meaning, dysphoria, disheartenment, and sense of failure. A new factor, not reported in the Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study, was also found in the current study. The five items closest to hopelessness and suicidal ideation (“I feel hopeless”; “No one can help me”; “Life is no longer worth living”; “I would rather not be alive”; “I feel quite isolated or alone”) loaded onto a new factor not reported in Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004), which has been named the Hopelessness Factor.

In agreement with Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study, convergent validity of the five factors and the Demoralization Scale was supported. However, contrary to the findings of their study, divergent validity of the DS was not supported; demoralized patients were significantly more likely to be depressed than those that did not score highly on the Demoralization Scale.

A key component of the reported validity of the Demoralization Scale reported in Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study was that demoralization was different from depression. In the current study, using appropriate cutoffs, high, medium, and low demoralization categories were determined and demoralization was compared with depression using chi-square analysis. A series of analyses was carried out, and the results conclusively showed the convergence of demoralization with depression in this study. The findings of the chi-square analyses in the present study did not support the assumption that demoralization differs from depression.

Moreover, Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) data were reanalyzed in the current study and their data were found to be similar to the current study, that is, no evidence for divergence was found. Kissane et al. wish to have the demoralization syndrome recognized as a distinct psychiatric condition from depression thus securing a place in the next DSM. Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) interpretation of the data was seriously inadequate and their failure to report any statistical information while concluding that their results supported the divergence of demoralization and depression was misleading. The current study has shown that it is premature to conclude for certain that demoralization is an emerging as a distinct entity in palliative care or whether the symptoms of demoralization define a depressive state in the context of advanced cancer. The results of the current study show that in an Irish palliative care context demoralization is not differentiated from depression.

This study also found significantly lower levels of demoralization in general compared with Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study. One hypothesis for the difference between the two samples relates to the high level of religious affiliation reported in the current study (83% Catholic; 9% Protestant). In the Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study, less religious affiliation was observed; 44% were Protestant, 25% were Catholic, and 23% were atheist or agnostic. Spirituality or religion were not measured in Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) study or the current study, and it is not possible to determine the level of psycho-spiritual well-being present in both samples. However, low levels of spirituality have been found to correlate with depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Rosenfeld and Breitbart2002; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Rosenfeld and Breitbart2003).

The current study included inpatients only and did not include any outpatients or those palliative patients in the community. The findings, therefore, may be less representative of the palliative care population in general. Moreover, the sample consisted of 100 advanced cancer patients attended by a specialist palliative care team and may differ, therefore, from other patients dying from cancer who are receiving less adequate palliative care. The majority of questionnaires were read out loud to participants in a face-to-face style interview in an effort to reduce the burden on patients. This method may have influenced patients’ willingness to endorse negative symptoms on the Demoralization Scale and other scales such as the Schedule of Attitudes towards Hastened Death.

Key strengths of the research warrant acknowledgment. Consecutive sampling over 18 months was a strength of this study. The findings of this study are likely to be very representative of an inpatient Irish advanced cancer population. A more comprehensive statistical analysis was carried out in this study than was presented in Kissane et al. (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004). The current study's categorization of the Demoralization Scale allowed for comparisons between individuals with low, moderate, and high levels of demoralization.

In conclusion, additional factor analytic studies are needed to fully validate the Demoralization Scale. Confirmatory validation is needed in another advanced cancer population and in other diverse groups that have been shown to be psychologically distressed, for example, motor neuron disease patients and immigrants and refugees. This study did not support the divergent validity of the Demoralization Scale. If future studies do not support the divergent validity of the Demoralization Scale, then revisions of the Demoralization Syndrome and its underlying assumptions should be considered. Future research needs to explore the associations between demoralization, depression, and hopelessness and consider whether demoralization is part of depression and hopelessness but not a separate entity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study received a support research grant of 1,500 euro from the Irish Hospice Foundation. The support was based on the concept of the study as opposed to a review of the full research protocol.