Introduction

Palliative care (PC) providers frequently discuss treatment options and goals of care for patients with life-threatening illnesses or those nearing the end of life. Evaluation of decision-making capacity is an essential component of PC practice. Delirium, a form of acute brain organ dysfunction characterized by inattention and changes in cognition, is a known independent risk factor for excess mortality, length of stay, cost of care, and long-term cognitive impairment (Ely et al., Reference Ely, Gautam, Margolin and Francis2001, Reference Ely, Shintani and Truman2004; Girard et al., Reference Girard, Jackson and Pandharipande2010; Lat et al., Reference Lat, McMillian and Taylor2009; Milbrandt et al., Reference Milbrandt, Deppen and Harrison2004; Pandharipande et al., Reference Pandharipande, Girard and Jackson2013; Shehabi et al., Reference Shehabi, Riker and Bokesch2010; Witlox et al., Reference Witlox, Eurelings and de Jonghe2010). Delirium is a common, serious, and potentially preventable condition that occurs in up to 88% of PC patients at the end of life and as part of the dying process (Close & Long, Reference Close and Long2012; Hosie et al., Reference Hosie, Davidson and Agar2013). If a patient is delirious, he or she is acutely cognitively impaired and therefore often lacks decision-making capacity and is unable to participate fully in a goals-of-care discussion.

Early recognition of delirium among patients at the end of life is imperative. Notably, PC patients have diminished reserve for a burdensome delirium assessment. A valid and reliable quick screening tool that can differentiate delirium from the multiple other medical morbidities experienced by PC patients is optimal. Early identification of delirium allows for expeditious treatment. Effective treatment of delirium could allow individuals to engage meaningfully with their loved ones at the end of life and enhance their decision-making capacity (e.g., to participate in goals of care discussions).

The development of standardized methods for delirium screening in the PC population, is a necessary first step in this treatment paradigm (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Davis and Ansari2014; Leonard et al., Reference Leonard, Nekolaichuk and Meagher2014). Brief standardized delirium assessments are an understudied part of the PC team approach for cognitive assessment for the purposes of determining decision-making capacity or to aid the patient's ability to meaningfully interact with their loved ones at the end of life. In this pilot investigation, we set out to validate a brief delirium-screening tool in a veteran PC population to improve delirium recognition in severe medical illnesses and at the end of life.

Methods

This was a pilot prospective observational study conducted at a tertiary, academic 146-bed Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC). The local institutional review board reviewed the project proposal and determined it was quality improvement and did not require full board review because the brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM) was being validated and implemented in the context of a larger quality improvement initiative to improve the recognition and treatment of delirium in veterans on the PC service. A convenience sample was enrolled. Enrollment occurred between July and December 2016 on days the psychiatrist and nurse (J.E.W. and L.B.) were available to perform paired evaluations of delirium. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were admitted to the PC unit or followed by the PC consultation service. Patients with a diagnosis of severe dementia, schizophrenia, or central nervous system disease (e.g., severe stroke, anoxic brain injury) were excluded from participation. Patients who met inclusion criteria were approached and verbally agreed to participate. If the patient was unable to verbalize understanding, a caregiver was approached and gave permission. No patients or caregivers who were approached for participation refused.

Measurement

The VAMC PC team (i.e., physicians, nurse practitioners, case manager, social worker) elected to use the bCAM to evaluate patients for delirium. The bCAM is a modification of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) and intended to improve sensitivity in noncritically ill patients (Han et al., Reference Han, Wilson and Vasilevskis2013). The bCAM takes less than two minutes to perform and uses objective and subjective testing criteria to determine the presence of altered mental status or fluctuating course (feature 1), inattention (feature 2), altered level of consciousness (feature 3), and disorganized thinking (feature 4) (Han et al., Reference Han, Wilson and Vasilevskis2013). A patient is considered to be delirious if both features 1 and 2 are present and either feature 3 or 4 are present. Validation of the bCAM with older emergency department patients demonstrated 84% sensitivity and 96% specificity when performed by a physician, and 78% sensitivity and 97% specificity when performed by a nonphysician (Han et al., Reference Han, Wilson and Vasilevskis2013).

For the study, two raters each independently assessed the patient for delirium. One rater (L.B.) performed the bCAM. She reviewed the bCAM training manual and watched instruction videos. The second assessment (reference standard) was a comprehensive psychiatric assessment of delirium, using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), performed by a consultation liaison psychiatrist (J.E.W.) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The psychiatrist has more than 10 years of clinical experience and routinely diagnoses delirium in clinical practice. To arrive at the diagnosis of delirium, the psychiatrist examined and interviewed the patient, spoke with the nurse and/or family members at the bedside, and reviewed the patient's medical record before making a final determination.

The bCAM was typically performed first with the psychiatrist's DSM-5 reference assessment performed within 30 minutes of the bCAM assessment. For most patients, we conducted a single set of paired assessments, but for 12 patients we conducted two sets of paired assessments, and for three patients we conducted three sets of paired assessments. Both assessors were blinded to each other's determinations. Results were recorded on paper case report forms and then transferred into an Excel spreadsheet by a medical student. Data were cleaned by L.B. and J.E.W.; two observations were dropped at the end of the study because of patients subsequently meeting ineligibility criteria for study participation (i.e., existing psychotic disorder or dementia.) One additional observation was dropped because the patient participated in a bCAM assessment but later refused DSM-5 assessment. Data entry was double-checked for accuracy. A medical record review was performed to collect age, race, admission diagnosis, and reason for PC consultation.

Electronic medical record review

A resident physician reviewed each patient's electronic medical record for documentation of a mental status evaluation, capacity evaluation, or for evidence of consideration of delirium by the PC service. J.E.W. and L.B. trained the physician to search for keywords suggestive of delirium or encephalopathy including capacity, fluctuation of mental status, confusion, and so on. Key words were collected, tallied, and used to create a Pareto chart.

Statistical analysis

To describe the study sample, medians and interquartile range are used to report central tendency and dispersion for age; proportions are used to present categorical variables. Sensitivity and specificity of the bCAM are presented with 95% confidence intervals using the DSM-5 assessment as the reference standard.

To use all available measurements while giving equal weight to each patient, before calculating sensitivity and specificity, we first down-weighted the observations from those patients with multiple observations. For example, if a patient had two observations that could be used in the sensitivity analysis, we gave each of those observations a weight of 0.5. We took the weighting into account in the calculation of confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity, using established survey-sampling techniques (Lumley, Reference Lumley2004). All statistical analyses were performed with R statistical software (version 3.3.2; http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Study population

We enrolled 36 patients who underwent 44 assessments. The median age was 67 years (interquartile range 63–73). The majority of our patients were male (n = 34, 94%) and white (n = 26, 72%) with either a high school education (n = 12, 33%) or some college (n = 12, 33%). The primary reason for admission to the hospital was sepsis or severe infection (n = 12, 33%). The reasons for PC consult or PC admissions were goals of care (n = 28, 78%), and pain or symptom management (n = 5, 14%). Additional study demographics are listed in Table 1. We conducted a total of 44 paired assessments on the 36 patients. Three observations were dropped for the reasons previously mentioned, leaving us with 41 paired assessments on 33 unique patients.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of enrolled patients

All items are n (%) unless indicated otherwise.

* Medians (IQR [interquartile range]) were used because the data for continuous variables were not normally distributed.

Sensitivity and specificity analyses

Twelve assessments on 10 unique patients were delirious according to DSM-5 criteria. Of those considered delirious according to DSM-5 criteria, 10 were also bCAM positive, yielding a sensitivity of 0.80 (0.40, 0.96). Twenty-nine assessments on 23 unique patients were nondelirious according to the DSM-5 criteria. Of those considered nondelirious according to the DSM-5, 25 assessments were also bCAM negative, which corresponded to a specificity of 0.87 (0.67, 0.96).

Pareto chart

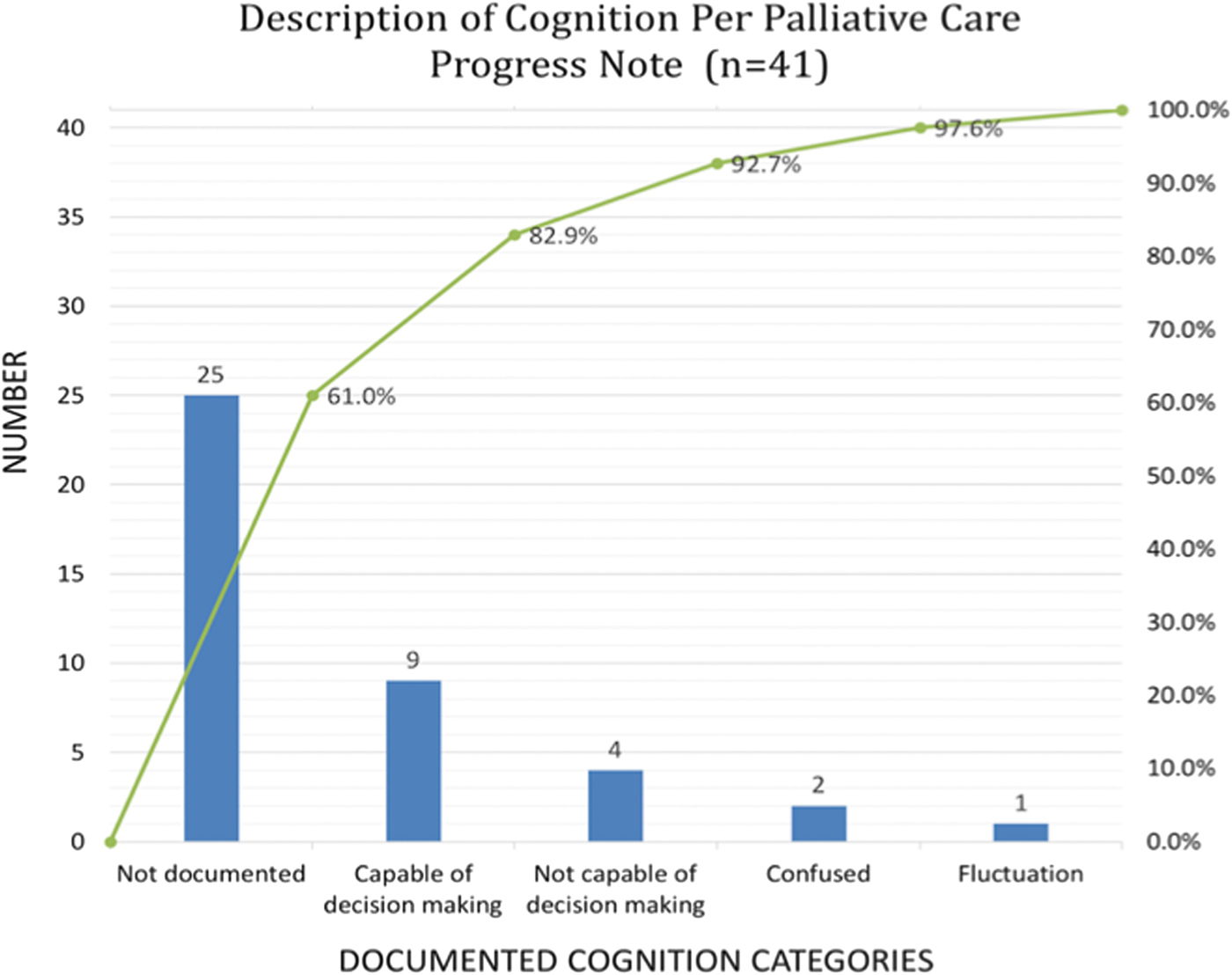

A review of the electronic medical record (Figure 1) revealed that, in the context of routine clinical care, 61% of the time (n = 25) there was no explicit mention of an evaluation by the PC service of the patient's cognition or capacity for medical decision-making suggestive of an evaluation for delirium, 32% (n = 13) documented capacity (or lack of capacity) to engage in medical decision-making, 5% (n = 2) documented “confusion,” and 2% (n = 1) documented “fluctuation” of mental status. There was no mention in any of the medical documentation by the PC service of delirium/encephalopathy nor of formal assessment of delirium by DSM-5 criteria or validated delirium-screening instrument as part of the clinical PC assessment and consult before or during this initiative and assessment period.

Fig. 1. Pareto chart is shown depicting number of assessments (n = 41) (left y-axis) and percent of time (right y-axis) that documentation regarding mental status or capacity was documented by the palliative care service in routine delivery of medical care in the electronic medical record. The light green curve (starting in the bottom left corner and extending to the top right corner) depicts the cumulative percent of assessments across documented cognition categories (blue bars). For example, 61% (N = 25) there was no documented evaluation by the palliative care service of the patient's cognition or capacity for medical decision making, suggestive of an evaluation for delirium.

Discussion

In this pilot investigation, we sought to validate the bCAM, a brief delirium-screening tool in PC patients at a single VAMC. We found that the bCAM provided good sensitivity and specificity for detecting delirium, with a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 87%. Anecdotally, PC team members reported the bCAM to be a quick and easy tool to evaluate for delirium within the veteran population. Delirium was not routinely screened for in this population and the presence or absence of acute mental status changes suggestive of delirium was frequently missed in routine clinical care. This discrepancy is remarkable, considering that 27% of patients (n = 10 of 36), in this pilot investigation, were delirious, according to DSM-5 criteria.

For the purpose of a comprehensive evaluation of delirium in the PC population, the DSM-5 or the International Classification of Diseases, 11th edition, should serve as the gold standard for a clinical diagnosis of delirium. In the PC setting, however, a comprehensive interview and examination may not be feasible nor tolerable given the severity of medical illnesses, and burden of medical interventions, especially with the shift of focus in care toward liberation from distress and suffering. A quick bedside assessment performed by a PC team member, nursing staff, or family would therefore be preferable to an exhaustive delirium assessment.

Previous studies have evaluated the use of the CAM, CAM-ICU, Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist, Delirium Rating Scale, and Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale in advanced cancer and PC populations (Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Caraceni and Beltrami2001; Neufeld et al., Reference Neufeld, Hayat and Coughlin2011; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Leonard and Guerin2009). The CAM and Delirium Rating Scale were found to be sensitive (88% and 80%, respectively) and specific (100% and 76%, respectively) for identifying delirium, but take >15 minutes to complete (Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Caraceni and Beltrami2001; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Leonard and Guerin2009). Likewise, the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale, primarily a delirium severity scale, was sensitive (68%) and specific (94%) for delirium in cancer patients, but takes >10 minutes to complete (Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Caraceni and Beltrami2001). Interestingly, the CAM-ICU and the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist were shown to be specific (≥98% for both instruments) but not sensitive for delirium in a noncritically ill oncology population (Neufeld et al., Reference Neufeld, Hayat and Coughlin2011).

This pilot investigation represents a first attempt to validate a brief (<2 minute) delirium-screening tool in a PC cohort and was found to have good sensitivity and good specificity in this population. Our hope is that this pilot trial would encourage others to pursue, in a larger scale format, the characterization, diagnosis, and treatment/management of delirium in this vulnerable patient population. By improving our recognition of delirium at the end of life, we may be able to better optimize cognition, garnering improved patient engagement with loved ones, and with the care team, hopefully improving their ability to be meaningfully present at the end of life.

This study has several strengths. The patient sample represents a diverse set of diagnoses beyond cancer with the largest number admitted for treatment of sepsis or severe infection. The investigators completing the bCAM and DSM-5 evaluations were blinded to one another's assessment results and completed the majority of paired assessments within 10 minutes of each other. Despite these strengths, the study also has important limitations. Our sample is a small, largely male, veteran-only sample and thus may not generalize to the larger PC population. In addition, the sample was one of convenience based on availability of the investigators.

Recognition of delirium is frequently missed in routine clinical care on the PC service. The bCAM provides good sensitivity and specificity in a pilot of PC patients, providing an efficient and effective method for nonpsychiatrically trained personnel to evaluate reliably for delirium. Further investigations using a larger sample are needed.

Author ORCIDs

Leanne Boehm, 0000-0003-0127-6677; Lauren R. Samuels 0000-0002-7273-5626.

Acknowledgments

J.E.W. and L.B. acknowledge that this work was partially supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Department of Veterans Affairs, VA National Quality Scholars Program, and with resources and the use of facilities at VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, TN. R.S.D., E.W.E., S.M., and J.H.H. acknowledge salary support from the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center. J.E.W. acknowledges salary support from the Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Research Scholars program (1KL2TR002245). L.B. acknowledges salary support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K12HL137943. J.E.W. has also received support from National Institutes of Health grants (GM120484, HL111111).

Conflicts of interest

E.W.E. discloses additional funding for his time from AG027472 and having received honoraria from Orion and Hospira for CME activity; he does not hold stock or consultant relationships with those companies. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.