INTRODUCTION

Family therapy has developed several approaches to framing questions within family meetings, but few of these techniques have been adapted for palliative care. Questions are the primary tool clinicians use to learn about the family's experiences (Main et al., Reference Main, Boughner and Mims2001). In palliative care, these questions help gather important information about various issues that concern families, such as care provision, coping, support, and discussion about death and dying. In general, questions are investigative or therapeutic in intent. Certain types of questions bring about more adaptive change within the family as they cope with the illness. Among the different questioning styles, circular questioning has been argued to be essential for successful outcomes (Fleuridas, Nelson & Rosenthal, Reference Fleuridas, Nelson and Rosenthal1986). Other authors have recognized that circular and reflexive questions facilitate joining to strengthen the therapeutic alliance (Dozier et al., Reference Dozier, Hicks and Cornille1998; Ryan & Carr, Reference Ryan and Carr2001).

One recurring criticism of existing clinical research is the startling lack of focus on clinician (and/or patient) behaviors that lead to important moments of change in family sessions (Beutler et al., Reference Beutler, Williams and Wakefield1993). As Pinsof and Wynne (Reference Pinsof and Wynne2000) astutely pointed out, our research thus far offers little guidance to therapists about their in-session decision making. Only a few studies target what is specifically helpful to the ongoing process of therapy (Johnson & Lebow, Reference Johnson and Lebow2000; Pinsof & Wynne, Reference Pinsof and Wynne2000). Outcome research has emphasized efficacy of a model of therapy rather than building a deeper framework that describes how it works.

Fortunately, the family therapy literature has developed conceptual models that can greatly benefit palliative care. Several authors have described and categorized questions—for instance, circular, reflexive, and narrative—along with illustrations of the purpose and use of such questions (Penn, Reference Penn1982; Fleuridas et al., Reference Fleuridas, Nelson and Rosenthal1986; Tomm, Reference Tomm1988; White & Epston, Reference White and Epston1990). For seasoned therapists, these illustrations favor the assimilation of the different types of interventions (Main et al., Reference Main, Boughner and Mims2001). However, as such illustrations have yet to be specified for palliative care, clinicians and therapists meeting with the families of advanced cancer patients can find it difficult to develop this style of family session.

In this article, we examine the clinician's questioning styles in its application to palliative care. More specifically, drawing on Tomm's (Reference Tomm1988) framework, we identify, classify, and exemplify questions used by a therapist across phases of a palliative care family intervention model, the Family Focused Grief Therapy (FFGT; which will be described below). In the next section, we present the conceptual model (Tomm, Reference Tomm1988) that we used to explore the style of questioning. In the section following that, we describe the method employed to classify the questions used across the phases of therapy and provide a case example to illustrate the adaptation of this model to the palliative care setting.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: TOMM's FOUR QUESTIONING STYLES

The Milan team (Selvini et al., Reference Selvini, Boscolo and Cecchin1980) identified three principles essential to an adequate family interview from a systemic perspective: circularity, hypothesizing, and neutrality. Neutrality refers to the idea of being “allied with everyone and no one at the same time” (Selvini et al., Reference Selvini, Boscolo and Cecchin1980, p. 11). Hypothesizing refers to the application one's cognitive resources in order to generate explanations. For Tomm (Reference Tomm1988), circularity reflects the therapist's ability to conduct an investigation on the basis of feedback in response to questions asked sequentially of different members about relationships. Tomm regards circularity as “a bridge connecting systemic hypothesizing and neutrality by means of the therapists’ activity” (p. 33). The Milan group first formulated the interviewing technique of circular questioning and Tomm subsequently introduced the concept of “interventive interviewing,” which refers to the use of a variety of categories of questions designed not only to obtain information for assessment but also to initiate, simultaneously, therapeutic change (Tomm, Reference Tomm1988). Tomm defines this concept as posing questions with the primary intent of influencing the family's processes rather than solely obtaining information from them. Interventive questioning is central to the systemic practice of family therapy, as it helps all involved developing a family-as-a-whole or systemic perspective rather than seeing issues purely as individual concerns.

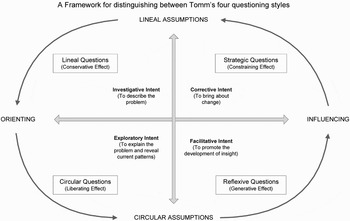

Tomm (Reference Tomm1988), a pioneer of Canadian family therapy, distinguished between four questioning styles in terms of the intentions and assumptions that they embody. With respect to intentions, therapists may pose questions in order to orient the family system through information gathering or to influence them and bring about change within the family. With respect to assumptions, therapists may ask questions based on linear (cause-and-effect) assumptions or on circularity (cybernetic) assumptions. The ability to differentiate between the linear and circular views is central to systemic thinking.

Linear assumptions break the ongoing flow of events into discrete segments, whereby A causes B, which in turn causes C. This presupposition “does not probe the interrelatedness of behavior and it gives the therapist a more single-minded approach to the etiology and understanding of individual, couple or family's behaviors” (Weeks & Treat, Reference Weeks and Treat2001, p. 49). In that sense, it can more easily lead to blaming by focusing the responsibility on a single person or event.

Circular assumptions embody a more holistic perspective, as they put the emphasis on the interconnectedness and recursiveness of human actions. In other words, circular assumptions not only include cause and effect explanations, but also extend the understanding to include the identification of relational patterns (reciprocity, mutuality, alliance, polarization, etc.). These assumptions are oriented toward a series of small cause-and-effect segments, which, when synthesized, create a larger circular pattern. Reciprocally interactional circular assumptions are at the core of systemic approaches (Tomm, Reference Tomm1988).

Distinguishing Questioning Styles

Linear questions are one-to-one questions used when history or specific information is desired. They generally take the form of a direct, open-ended question to an individual, who is asked to give his or her account of the story. These questions have an investigative intent.

Circular questions seek observational information from one family member about others, one or more members, by asking the respondent to step into the shoes of the others. They serve as an efficient process for soliciting information from each member of the family regarding his or her opinion and experience of (a) the family's current concern; (b) sequences of interactions, usually related to the problem; and (c) differences in their relationship over time (Weeks & Treat, Reference Weeks and Treat2001). Circular questioning can help family members to realize that a given issue can be understood differently by one member compared to others and, in doing so, to move toward a more “decentered” point of view.Footnote * Circular questions are especially useful when the clinician believes a family member could benefit from gaining more empathy from others in the family.

Reflexive questions are posed to invite family reflection and autonomous problem solving. They help family members to recognize how their various reactions, behaviors, and feelings serve as triggers and dynamically influence the family's interactions. In so doing, they encourage family members to take a step back and look at the family's issues and patterns from a more disengaged and objective perspective. Reflexive questions are likely to enable the family to generate new insights or solutions by “embedding a working hypothesis into a question (hypothesis introducing)” (Tomm, Reference Tomm1988, p. 172). In this way, the therapist can draw new options from the family's beliefs system.

Strategic questions are commonly used to invite the family to examine potential solutions to a problem and to bring about change within the family. These questions suggest possible alternatives for action to the family, but may have a constraining effect in limiting further options (Tomm, Reference Tomm1987a and Reference Tomm1987b).

An intersection of the two continua of intent (with poles of orienting and influencing styles) and assumptions (with poles of linear and circular assumptions) offers a framework for distinguishing between these four types of questions (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Tomm's (Reference Tomm1988) four questioning styles.

In summary, there are two types of information-gathering and orienting questions, one based on linear assumptions (linear questions) and the other based on circular assumptions (circular questions). Similarly, two modes of change-focused or influencing questions emerge from each type of assumptions: Strategic questions are more linear in nature, whereas reflexive questions tend to be more circular. Linear and circular presuppositions should not, however, be considered as mutually exclusive. As Tomm (Reference Tomm1988) astutely pointed out, “the distinction between linear and circular may be regarded as complementary, and not just as either/or, these assumptions and their associations may overlap and enrich one another” (p. 4).

In the next section, we apply this theoretic model to an analysis of questioning styles in family therapy during palliative care.

METHODS

Participants

We examine the longitudinal course of therapy for a family taking part in the FFGT. This is a preventive, brief, and time-limited model of family therapy delivered to high-risk families during palliative care and bereavement that seeks to improve family functioning and exploration of the family's cohesiveness, communication, and resolution of conflicts. Each session lasts 90 minutes, and the intervention includes three phases: assessment (two weekly sessions), involving identification of issues or concerns relevant to the family; intervention (typically four to six biweekly to monthly sessions), focusing on agreed concerns; and termination (one or two sessions two to three months apart). The total number and the frequency of sessions are adapted to each family's needs.

Procedure

Classification of Questions

Audiotapes of each session were appraised to identify and classify, based on Tomm's (Reference Tomm1988) framework, the questions asked across the phases of the FFGT. To ensure faithful application of the manualized model of FFGT, therapists are trained through a series of workshops and weekly supervision (peer group model). The families were recruited as part of a National Cancer Institute-funded study of dose intensity of FFGT. Ethical approval was given by each site's Institutional Review Board; families gave informed consent.

Development of an Observational Rating Scale

A glossary of definitions and an observational rating system were developed by the first author to identify and classify each question used by the therapist across the phases of therapy. Some items examined the frequency of each style of questioning; others assessed the ability (competence) of the therapist to use the different types of questions appropriately in the context of therapy using Likert-type scales (ranging from not at all to comprehensive). Individual observations between two raters (the authors of this article) of 351 questions overall (from eight reviewed sessions) for six items were compared, from which percentage agreements were determined to ascertain interrater reliability.

RESULTS

Interrater Reliability

Two raters independently coded transcriptions of the audiotapes of eight sequential family sessions. Observations were compared and percentage agreements determined to ascertain interrater reliability. The agreement between raters achieved an overall average of 90% as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean Interrater Agreement over Questioning Styles within FFGT

IR: interrater reliability; N: number of observations (questions) compared.

Occurrence of Orienting and Influencing Questions across the Phases of Therapy

At the beginning of therapy, the most frequent questions were linear and circular, moving around the family to build up a picture of events from everyone's perspective. Indeed, the mean occurrence of orienting questions (linear and circular) during the assessment phase was 96% compared to 78% during the focused phase of therapy and 38% in the termination phase. As for the frequency of reflexive and strategic questions, these increased as the therapy progressed, bringing the family to new perspectives. The mean occurrence of influencing questions (reflexive and strategic) during the assessment phase was 4% compared to 22% during the focused therapy phase and 62% in the termination phase. These results are shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Percentage of occurrence of orienting and influencing questions across phases of therapy.

The observational rating system had some discriminatory ability in showing the transition from a high use of orienting questions in assessment phase compared to a steady rise in the use of influencing questions during active treatment. The following case example illustrates the use of interventive questions, which could be used as part of the training offered to therapists in psychooncology and palliative care.

Deidentified Case Example

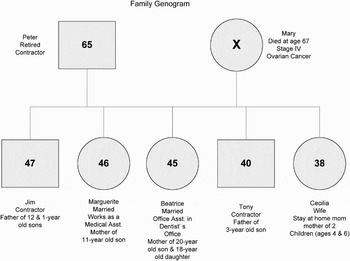

Mary, her husband Peter, and their three daughters and two sons (see Fig. 3) took part in 10 sessions of the FFGT. Mary, an Irish Catholic, was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in February 2003. She and her husband had been married for 50 years. Sessions were held at the family home, where all the children had grown up. These offspring lived close by with their own spouses and children. The family members appeared close and protective of each other. Indeed, the family's intuitive self-protectiveness got in the way of members’ expression of opinions and feelings. Humor was used to mask sadness. When alive, Mary played an important role as a mediator between the father and the five children. She was also seen as a caretaker for her husband, who often felt lonely. Mary died after four sessions of therapy. At that time, Peter, the father, became really demanding of his children who, in turn, felt burdened by his numerous requests. The family meetings offered a safe place for the family to discuss their concerns and feelings; frustrations were expressed, grief shared, and differences of opinion acknowledged.

Fig. 3. Genogram of family presented in the deidentified case example.

Early Phase of Therapy: Orienting Questions

In the initial stages of the therapy, orienting questions (linear and circular) were used most frequently. Linear questioning was used to gather information about the family's concerns and its understanding of the illness and prognosis. The therapist joined with the family and encouraged participation of each member. Linear questions helped develop understanding of the family's dynamics. The following examples illustrate some linear questions used:

To Mary:

“Can you talk a little bit about the illness?”

“How have treatments been going?”

“What is your understanding [of the illness]?”

“What are the doctors saying?”

“Physically, how are you feeling?”

“How did you manage your day today?”

To every family member:

“Can you give me a sense of what you do?”

“What are your expectations of these meetings?”

“What do you think you would like to get out of these meetings?”

“What are you the most concerned about right now?”

“How hard is it for you to talk about the illness?”

“Is there anything you would like to talk about as we move forward with the meetings?”

“What have you told your spouse and your children about Mary's illness?”

In addition, the therapist was able to get a richer understanding of the impact of the illness through circular questions. These led to a description of the family's functioning and cohesiveness. Family coping strategies were made explicit. The following examples illustrate the circular questions asked by the therapist.

To Peter:

“How concerned do you think Mary is about you?”

“How concerned do you think your kids are about you?”

To the children:

“Can you tell me a little bit about your mom's role and your dad's role in the family? What similarities and differences?”

“How do you think your mom is doing?”

To each family member:

“Who are you the most worried about right now?”

“Who is especially close within the family?”

“How do you connect with each other?”

“Who is closer to whom?”

“Have you guys gotten closer since the diagnosis?”

“It's been several months since Mary died; have you guys gotten closer?”

“How do you connect with each other when you're missing your mom?”

Later Phases of Therapy: Influencing Questions

As therapy progressed, use of reflexive and strategic questions increased. These were asked to create insight and to promote change. Families living with illness are often preoccupied with the difficulties at hand and struggle to imagine a world without their loved one; they see few, if any, alternatives or choices for the future. By asking reflexive questions that were future oriented, the therapist empowered the family to create a sense of a future. The family prepared itself for their loss as they cared for their dying mother. The following examples illustrate this type of questions.

To each family member:

“What are your hopes for the future?”

“How hard is it to talk about death and what might be the future?”

“What are your expectations for the future?”

“When will you know that you need to meet like this again, that you will need each other?”

“What do you think you would all need from each other?”

“What do you think will look different in a year?”

To Mary:

“As things become harder for you physically, what roles will the kids and Peter take on?”

“What do you think would happen if people saw you that way [physically sick]?”

When it is difficult for the family to talk about death and dying, the therapist can seek the family's permission by asking a question like: “Would it be useful to talk about a hypothetical time ahead when Mary will no longer be with us?” Raising the theme of anticipatory grief is helpful by asking each member to share their concerns about the imminence of death. Examples of reflexive questions that the therapist could have asked to help the family to prepare for Mary's impending death include “In a year, what issues will each one of you will need to consider?” “Whose life might be most affected at that time?” “How will those issues be affected by Mary's illness?” “Given Mary's illness, are there certain expectations about how Peter should plan for the next phase of his life?” The following questions were powerful in building solidarity around Mary and helping Peter and the children to think about their experience differently.

To the children and the spouse:

“If Mary (who passed away 8 months ago) was here in the session right now, what would she tell you as a family?”

“What do you think your mom would want?”

When Mary passed away, Peter reported feeling alone and became so dependent on his children that they felt burdened by his multiple demands. Peter carried high expectations, looking for care in the manner Mary had provided for him. It was challenging for Marguerite, one of the daughters, to whom Peter said, “You told your mom that you'd take care of me.” The therapist encouraged Marguerite to talk with her father more directly about her feelings. Strategic questions helped Marguerite gain new insights and shift attitude toward her dad.

To Marguerite:

“Are you able to tell your dad when he does call that it's too much sometimes?”

“Is there a way you can just hear your dad talking and not get pulled into feeling that way?”

The therapist challenged Peter's understanding of this:

To Peter:

“When you hang out with the kids and you are reminded of something Mary would have done differently [than the kids], what do you expect the kids to do, how do you think they feel?”

“Peter, why don't you reach out to other people besides the kids?”

DISCUSSION

Dozier et al. (Reference Dozier, Hicks and Cornille1998) investigated response differences to questions based on circular assumptions (circular and reflexive questions) as opposed to questions that are based on linear assumptions (linear and strategic questions). According to their findings, circular and reflexive questioning facilitates joining and therapeutic alliance in therapy. Ryan and Carr (Reference Ryan and Carr2001) also confirmed this experience. As Dozier et al. pointed out, the major implication of these results is that the type of questions the clinician uses in therapy “may be the critical factor that determines the level of joining the therapist system is able to make with the patient system” (p. 8). Only a few studies, however, have tested this belief empirically (Dozier et al., Reference Dozier, Hicks and Cornille1998; Ryan & Carr, Reference Ryan and Carr2001).

Mary's family highlighted the value of each type of question, all of which have a proper place in the course of therapy (Tomm, Reference Tomm1988). When the clinician wants the family to understand a problem like a progressive illness, linear questioning is useful. Linear and circular questions also help the therapist to join with the family by getting a description of who they are (e.g., questions about their names, ages, occupations, relationship with the ill person, etc.). When the clinician wants the family to consider whole-of-family patterns and behaviors, circular questioning is extraordinarily useful.

Circular questions were particularly useful in understanding differences between family members and their ways of relating to each other. Tensions and conflict from differences of opinion can create trenches between family members, causing a negative experience of the illness and grief (Dumont, Dumont & Mongeau, Reference Dumont, Dumont and Mongeau2008). Circular questions enabled the therapist to construct a more holistic view by translating the information into processes and relationships. Furthermore, because family members initially perceived issues from their personal point of view, the circular questions helped the family redefine the predicament as a family system issue, which we know can bring about benefit (Weeks & Treat, Reference Weeks and Treat2001).

Once the therapist has a clearer understanding of the issues involved, change-focused questions (reflexive or strategic questions) come into play. Family members can be locked into seeing certain events from one perspective and are unable to see other potential behavioral options. Questions can be used to explore paradoxical content, context, or meaning (Tomm, Reference Tomm1988). Thus, reflexive questions can be useful when a resilient family has a cognitive and behavioral repertoire from which they can draw to solve problems. They foster active participation and a degree of autonomy at the same time. In the context of palliative care, reflexive questions help both therapist and family see the extent to which the illness influences and controls family life (Rolland, Reference Rolland1994). Such questions also help the family to share grief adaptively after the death. Their expression of thoughts and feelings promotes support and counters the loneliness often associated with bereavement (Kissane & Bloch, Reference Kissane and Bloch2003). Strategic questions also stimulate the family to consider new directions by embedding overt suggestions. Difficulties occur when family members hold tightly to existing beliefs and do not seek new information or perspectives (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Carroll and Watson2005). In the examples presented earlier, the therapist tries to influence understanding by using strategic questions. By embedding a suggestion, strategic questions can guide the family to move in a new direction.

In sum, orienting questions (linear and circular) are useful in describing the family's concerns and in explaining and revealing the current family patterns. In contrast, influencing questions (reflexive and strategic) can help move the family toward new insights or solutions by embedding new perspectives or solutions.

Implication for Clinical Practice

Here we have provided examples of questions that can be used by clinicians working with advanced cancer patients and their families. We believe this style of interviewing can be mastered by a thoughtful clinician with appropriate training, which focuses on questioning styles and can be tremendously empowering of families during palliative care and bereavement. Mobilization of the family's strengths and resources creates an environment likely to optimally foster adaptation despite the pain of loss. If empirical researchers wanted to explore these issues further, they could examine the role of summary statements and reframing to refine their benefit. Exploration of therapeutic interventions across a range of families is time-consuming and arduous but eventually necessary to better understand the process of change.

It would also be enlightening to study the therapist's impact on the family from a systemic epistemology. Study could be made of the family members’ reactions to the therapist's interventions and also the family within the context of the therapy (Elliott & James, Reference Elliott and James1989). Multiple data sources and research methods generate a rich understanding of family therapy process. Such an approach would involve, inter alia, asking the family members to identify significant events from the sessions and asking them about their reactions (positive and negative) to the therapist's interventions (for example, using the Client Recall List, Elliot, Reference Elliott and James1989; or the Client Reactions System: Hill et al., Reference Hill1988).

CONCLUSION

Much contemporary education to create a psychotherapist is grounded in a linear way of thinking common to individual therapy. It can be challenging for clinicians to reorient their conceptual perspectives to assess families in a circular or systemic manner. Tomm's (Reference Tomm1988) interventive questioning model can guide supervisors, trainees, and clinicians seeking to build skills and optimize their interventions. The framework offers guidelines to help facilitate decision making about what kind of question to ask.

Traditionally, process researchers have focused on examining change moments in therapy as one-way interventions delivered by the therapist. Few researchers have investigated how therapists and families construct change through the back-and-forth reciprocity of their conversations (Couture, Reference Couture2006). This is an important area of focus to understand how change is co-constructed within therapeutic interactions. Although we will not try to develop and justify this assertion here, family therapists view this construction as occurring through nonlinear, ongoing circular processes. As we study the therapist's interventions together with the family's reactions, “Over time, it will be difficult to even isolate one person's actions as separate or unconnected from the interaction of the social group” (Gale et al., 1993, quoted in Couture, Reference Couture2006, p. 4). In so doing, a more systemic way of thinking is more likely to weave its way through the linear mode of thought that is deeply ingrained in our implicit or prereflexive epistemology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was conducted with support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (756-06-0442).