Introduction

Asia is home to over one-third of the world's population aged 65 and above. It is also the region undergoing population aging more rapidly than any other since the early twenty-first century (World Bank, 2016). Such unprecedented rise in the number of older people will inevitably translate into much larger demands for health and social care, particularly those required at the end-of-life. This necessitates a transformation of service delivery that must reflect stronger health system coordination (Gibson, Reference Gibson and Conway2011), as well as more informed citizenry, that assumes greater responsibility for their own health and mortality (Ho and Chan, Reference Ho, Chan and Conway2011). In fact, the World Health Organization (Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance, 2014) consistently urges regional governments to establish national strategies and comprehensive action plans for developing sustainable palliative care services and advance care planning programmes in order to meet the needs of older patients facing chronic terminal illness. However, the palliative care environment in most Asian societies remains largely underdeveloped (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015), with the three exceptions of Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong; all of which have established some forms of national initiative, legislation, or models of financing that support palliative care.

In Singapore specifically, a comprehensive National Strategy for Palliative Care was formulated by the Lien Foundation in 2011, following consultation with key health and social care stakeholders, and accepted by the government (Lien Centre for Palliative Care, Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School, 2011). In the same year, the first-ever National Advance Care Planning (ACP) programme in Asia, titled “Living Matters”, was launched by the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC), an independent corporate entity funded and monitored by Singapore's Ministry of Health. “Living Matters” aims to empower its citizens with greater autonomy in making informed end-of-life care decisions through open and honest conversations about treatment preferences between patients, their families, and their professional caregivers (Singapore: Living Matters, 2019). With this national initiative, Singapore has arguably made the most advanced progress in palliative care practice and policy within Asia.

Advance care planning

ACP is defined as “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals and preferences regarding future medical care … and to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals and preferences during serious and chronic illness” (Sudore et al., Reference Sudore, Lum and You2017). Since its emergence in the United States during the mid-1970s and driven by the goal of patient self-determination (Sabatino, Reference Sabatino2010), ACP has gained increasing attention from health and social science researchers around the world for its potential to improve value-aligned medical care (Silveira et al., Reference Silveira, Kim and Langa2010), to facilitate end-of-life care decision-making (Houben et al., Reference Houben, Spruit and Groenen2014), and to enhance the quality of death (Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, O'Caoimh and Cornally2016). With the intention to uplift patient autonomy and improve resource efficacy, it is not surprising that ACP has become a core component of palliative care in the twenty-first century (Kelley and Morrison, Reference Kelley and Morrison2015).

Given its clinical and policy-centered significance, numerous studies have explored the perspectives, attitudes, and experiences of ACP among different stakeholder groups including healthcare workers, patients, and family caregivers (Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Moran and Kuhn2013; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Dai and Lam2016; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Butow and Kerridge2016; Becket al., Reference Beck, McIlfatrick and Hasson2017). Two recent overviews of systematic reviews that investigated the current state of ACP research reported that despite the potential benefits that ACP can bring to palliative care, the quality and outcome of ACP can be affected by numerous sociological and systemic factors including, but not limited to, cultural beliefs, public perceptions, buy-in from healthcare workers, service coordination, organizational support, complexity of intervention, programme evaluation mechanisms, as well as relevant legal and judicial policies (Jimenez et al., Reference Jimenez, Tan and Virk2018a, Reference Jimenez, Tan and Virk2018b). The authors further argued that in order to fully understand and promote best practices in ACP, a holistic investigation of programme development and implementation is warranted with different stakeholders across various healthcare settings.

Due to the lack of formal ACP programmes in Asia, no relevant study has ever been conducted in the region, leaving a critical knowledge gap that hinders advancement in palliative care practice and policy. The aim of this study is to critically examine the developmental underpinnings of Singapore's recently established Living Matters initiative, as well as to systematically identify the dynamics, mechanisms, and systemic factors that influence its implementation, outcomes, acceptability, feasibility, and sustainability. Such understanding can inform and improve health system coordination and palliative care provision in Asia, enabling regional governments to develop their own ACP programmes so as to provide much-needed care and support for those facing death, dying, and loss.

Living Matters: Singapore's advance care planning programme

Singapore's Living Matters is modeled after the ‘Respecting Choices’ programme originally developed by the Gundersen Health System in Wisconsin, United States, of which was found to be effective in increasing patient–surrogate congruence in end-of-life care decision-making, enhancing compliance with care preferences, and bolstering higher satisfaction with the quality of death (Song et al., Reference Song, Kirchhoff and Douglas2005). Based on this clinical model, the ultimate goal of Living Matters is to encourage more end-of-life care discussions between individuals, families, and healthcare providers via the three objectives of (1) increasing awareness of ACP in the community and among health and social care sectors through various outreach initiatives; (2) recruiting and training an adequate pool of certified ACP facilitators to render the Living Matters programme proficiently; and (3) building and strengthening existing health and social care systems across all regions of Singapore to support ACP implementation.

In order to achieve these objectives three major policy and protocol centered enterprises were undertaken, including (1) the development of a national ACP training programme for health and social care workers; (2) the standardization of a documentation protocol for carrying out ACP conversations with different patient profiles; and (3) the establishment of a national ACP IT infrastructure to record and retrieve the end-of-life care preferences of those involved in the programme. Living Matters does not require individual institutions to adhere to a standardized protocol in the delivery of ACP but allows for flexibility within each institution to establish an appropriate service model to meet its need. With the support and leadership of AIC, eight major public general hospitals and specialist centers across Singapore are rendering ACP in various capacities; these include Changi General Hospital (CGH), Ng Teng Fong General Hospital (NTFGH), National University Hospital (NUH), Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH), Singapore General Hospital (SGH), Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH) and KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH), and the National Heart Centre Singapore (NHCS). Since its inauguration in 2011, more than 1,400 physicians, nurses, social workers, and allied health workers have graduated from the national ACP training programme and assumed the role of ACP facilitators (Koh, Reference Koh2015), and approximately 10,000 ACP conversations have been documented across the nation (Foo, Reference Foo2017).

In practice, Living Matters promotes family-centered ACP discussions that take into account individuals’ health statuses when making decisions on end-of-life care treatments. The target populations comprise of three major adult groups including individuals suffering from life-limiting illnesses with a prognosis of less than 12 months (Preferred Plan of Care ACP or PPC-ACP), those with progressive and complex chronic conditions (Disease Specific ACP or DS-ACP), as well as healthy people and those with early chronic diseases (General ACP). In all three formats, individuals nominate a healthcare spokesperson (who is usually a family member) and together with an ACP facilitator, decide on a plan of care should the individual become mentally incapacitated. For those enrolled in PPC-ACP, care goals on medical intervention in the event of life-threatening crisis, as well as preferences on place of care and place of death are specified. For those enrolled in DS-ACP, specific disease-related care and goals of treatment following medical complications are defined.

ACP conversations may be completed through one or multiple conversations depending on the knowledge and readiness of patients and their families. At the conclusion of an ACP conversation, patients are asked to sign an official ACP document that details their specific care preferences. Patients may choose not to sign the document, and simply employ the knowledge obtained through the conversations as their own preference of care in the future. Signed ACP documents, while not legally binding, are further endorsed by patients’ primary physician and entered into a national ACP IT system for guiding care decisions during the final phases of life. Recognizing that patients’ needs and wishes may change across time, ACP facilitators encourage ongoing conversations so that ACP documents can be revised as needed. Given the complexity in programme design and the interdisciplinary approach in service provision, a comprehensive understanding of the development and implementation of Living Matters necessitates holistic inquiry that allows for multiple perspectives and interpretations of experiences from all stakeholders involved.

Methods

Study design

This study was part of a formal evaluation of Singapore's national ACP programme. It adopted a qualitative focus group design that accentuates systemic and systematic inquiries to examine the development and implementation of ACP. To attain a comprehensive understanding of Living Matters’ operational dynamics, two theoretical frameworks commonly used in systems research and implementation science were adopted.

First, the Interpretive-Systemic framework (ISF) (Fuenmayor, Reference Fuenmayor1991) guided the initial process of inquiry. This involved eliciting views and perspectives from all professional stakeholders who played critical roles in and were significantly affected by the Living Matters initiative, of which included physicians, nurses, social workers, and allied health workers hired specifically for the role of an ACP coordinator. This multi-level framework of inquiry enables a systemic understanding of ACP development and implementation through the interpretive lens of different stakeholder groups that belong to the diverse contextual systems of health and social care (Ochoa-Arias, Reference Ochoa-Arias1998).

Second, the conceptual taxonomy of implementation outcomes by Proctor and colleagues (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan2011) guided the focus of inquiry. Proctor's taxonomy is conceived as the impact actions taken to implement a new intervention programme, with conceptually distinctive outcomes to assess successful implementation. This study employed the five outcomes of acceptability, fidelity, feasibility, penetration, and sustainability to elicit stakeholders’ experiences in service provision, enabling a systematic understanding of ACP development and implementation. In sum, the integration of the ISF and Proctor's taxonomy allows for the generation of new ideas for informing clinical practice and policy formulation.

Ethical approval was obtained through the Institutional Review Board of Nanyang Technological University (Ref. No.: IRB-2016-05-023) and the Domain Specific Review Board of National Healthcare Group, Singapore (Ref. No.: 2016-00603).

Participant recruitment

Guided by the ISF, at least two participants from each of the four specific stakeholder groups involved in Living Matters, and who represent the seven major hospitals and specialist centers in Singapore, including CGH, NUH, KTPH, SGH, TTSH, KKH, and NHCS, were recruited to participate in the study. Such purposive sampling provided coverage that span across all major public healthcare systems. Stakeholder groups were further subdivided according to the level of experience with ACP provision defined in terms of number of ACP conversations conducted. The ‘experienced’ subgroup is classified as stakeholders who had conducted more than five ACP conversations, and the other subgroup of “trained” stakeholders were trained in the process but had five or less ACP conversations conducted. This allows for greater inclusivity of perspectives. The inclusion criteria included individuals aged 21 and above, who had graduated from the national ACP training programme, were actively involved with Living Matters, could communicate in English and provide informed consent. Under this frame, 12 physicians, 15 nurses, 24 medical social workers, and 12 ACP coordinators were purposively recruited (N = 63).

Interpretive-systemic focus groups

A total of 14 independent focus groups and mini-focus groups, comprising two to eight participants, were conducted between September and November 2016. Mini-focus groups with two to three people can create similar dynamics of a regular focus group to promote interactive discussions, especially when the involved participants possess high levels of expertise on the subject matter and engage in an open dialogue to potentially generate new perspectives on a specific phenomenon (Kamberelis and Dimitriadis, Reference Kamberelis and Dimitriadis2005; Nyumba et al., Reference Nyumba, Wilson and Derrick2018). Each focus group only comprised participants from each of the four stakeholder groups to maintain homogeneity. This served to minimize potential biases in data collection due to the inherent power differential between different professionals within a healthcare system. To collect rich narratives and multiple interpretations of Living Matters, the topics of all focus group discussions are based on Procter's taxonomy of implementation outcomes (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan2011). Specifically, participants were asked to comment on five major areas including (1) acceptability in terms of their views and experiences with end-of-life care conversations; (2) fidelity with regards to their experiences in conducting ACP conversations and ways to engage patients and families in such dialogues; (3) feasibility consisting of their views on patients’ and families’ receptiveness to ACP and the challenges that they have faced in meeting patients’ end-of-life care preferences; (4) penetration as defined by ACP buy-ins from their institutions as well as their team members; and (5) sustainability operationalized as their hopes for ACP and ways to ensure its continuous development.

All focus groups were conducted by a lead doctoral-trained qualitative researcher with no prior relationship with any research participants, together with two to three co-moderators who were full-time research staff and PhD students provided with training and close supervision by the research team. This procedure served to instil impartiality, minimize potential data collection biases, and ensure research triangulation. Each focus group took approximately 120 min to complete and were conducted in a quiet room at the university; they were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed. Apart from focus group discussions, participants were also asked to complete a simple demographic form comprising questions on age, gender, ethnicity, and numbers of ACP conducted, as well as the Death Attitude Profile-Revised (DAP-R) questionnaire that assessed their attitudes towards mortality, particularly those concerning fear of death and death avoidance (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chan and Chow2010).

Data analysis

Framework analysis with both deductive and inductive approaches was adopted to analyze the data for generating themes that illuminate the development and implementation of Living Matters. Framework analysis is developed for applied policy research with specific questions, purposive sample, a priori issue, and aims to meet specific information needs for generating outcomes or recommendations (Ritchie and Spencer, Reference Ritchie, Spencer, Bryman and Burgess1993). The QRS NVivo software was used for coding, cross-referencing, storing, and retrieval of data. The process of analysis involved several steps of coding. First, multiple readings and line-by-line coding were carried out by five members of the research team; written summaries and codes of the system dynamics that led to effective or ineffective programme development and implementation of Living Matters were consolidated into a data matrix. Secondly, axial coding was conducted to refine and relate possible categories of responses; text files containing illustrative and descriptive quotes supplementing the emergent themes and sub-themes were also created via a summary chart. Third, the same five members of the research team individually reviewed and defined the emergent themes and presented their analysis to one another as well as the principle investigator for discussion and confirmation; once consensus was reached, operational definitions were created. Finally, relationships between categories, themes, and sub-themes were proposed and mapped with supporting quotes from transcripts. To address issues of trustworthiness and credibility, emergent themes were constantly compared within and across groups during regular meetings, the final theme categorizations and definitions were agreed upon by the entire research team, and members-checking was conducted with selected research participants from all seven participating institutions.

Results

Table 1 presents the background information for all stakeholder groups. Overall, stakeholders were aged 25–63 (±SD 9.8 years), 52 were females and 8 were males. 55 stakeholders were Chinese, 9 were Malay, 2 were Indian, and 2 were of other ethnicities. Among all four stakeholder groups, ACP coordinators completed the highest number of ACP conversations, followed by nurses, social workers, and physicians, respectively. Responses to the DAP-R questionnaire show that all stakeholders held generally negative attitudes towards mortality, with group mean scores of 4.6 (±SD 1.15) on the fear of death subscale and 5.4 (±SD 1.15) on the death avoidance subscale, both of which ranged from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating higher fear and avoidance. It is interesting to note that among all stakeholder groups, physicians scored highest on both measures of fear of death and death avoidance.

Table 1. Characteristics of key stakeholders

Framework analysis revealed 19 themes that elucidate the dynamics, mechanisms, and systemic factors that underscore ACP development and implementation in Singapore. These themes overlap across all four stakeholder groups, reflecting the important roles that social attitudes, societal readiness, programme planning, and intervention operations play in the effective provision of ACP within the Asian context. The 19 themes are further organized into five major categories of: (1) life and death culture; (2) ACP coordination; (3) ACP administration; (4) ACP outcomes; and (5) sustainable paradigm shift. Each of these categories and their respective themes is considered in turn and supported by illustrative quotes organized in Box 1–Box 5

Box 1. Life and Death Culture

Theme-1: Death Aversion

“My parents are superstitious. The word dying is not something they want to hear. If you keep saying that it will be cursing them.” (Nurse, Female)•

“It can be a cultural thing that they don't want to talk about death. I am suspecting maybe they think it's bad luck they are in hospital, they want to get better.” (Doctor, Female)

Theme-2: Biomedical Model

“Patient has a fever. So, we're treating, fever, fever, fever. But then we fail to look at the person as a whole.” (Doctor, Female)

“I used to have a neurosurgeon that tells me, I only look at the brain. The rest you don't come and look for me.” (ACP Coordinator, Female)

Theme-3: Health System Hierarchy

“Patients have reached the end, there can be comfort measures… But some doctors will just come in and say “no, we need to do more”. They kind of push the whole thing around.” (MSW, Male)

“The culture is that the medical supremacy was there… The family believes the doctors more than the nursing staff. So they probably want to hear from the physicians before they actually come to the nurses.” (Nurse, Female)

Theme-4: Health-Seeking Behaviors

“Our patients, a lot of them see doctors as the authority. They don't dare to question things… Doctors speak very complicated languages.” (MSW, Male)

“I think elderly patients feel that their children are more educated, so they feel more comfortable when their children take charge. (MSW, Female)

Life and death culture

The first major theme category, “Life and Death Culture”, depicts the pre-existing social context that ACP is embedded in (see Box 1). Specifically, all participants expressed the imperative need to carefully consider the socio-contextual factors that influence public acceptability before programme implementation. Overall, there is a unifying consensus that “death aversion” (theme 1) is prevalent in Singapore, as with many other Asian societies. In actuality, death taboo is deemed one of the most significant factors that discourages individuals and families to engage in end-of-life conversations due to its ominous implications. Moreover, many participants expressed that the current provision of healthcare is driven predominantly by a “biomedical model” (theme 2) that focuses on saving and sustaining life. Despite the aspiration towards a more holistic bio-psycho-social model of healthcare that equally values both curation and palliation, the biomedical model continues to reign, and the consequence of such practice is the persistent prescription of aggressive treatments for patients nearing the end-of-life, as well as physicians’ reluctance to make palliative care referrals for those who need them.

A biomedical model has also led to a “health system hierarchy” (theme 3) that operates within a pyramid of power and authority between professional disciplines, placing physicians in a position of clinical leadership that can greatly influence both medical and social care decisions and outcomes. Despite the appeal to adopt an interdisciplinary team-based approach to care, health and social care professionals often find themselves operating within their own disciplines with little say on patients care plan, as such decisional capacities are dominated by physicians. The impact of medical authority is widespread, affecting also the “health seeking behaviours” (theme 4) of individuals and families, particularly among older adults. Many stakeholders expressed concerns over elderly patients’ dependency on their medical team in making important care decisions for them, instead of acting with greater autonomy. Dependent health-seeking behaviors are also prominent among families motivated by filial piety to act in the best interest of elderly patients, who are deemed to have low health literacy and thus incapable of making informed care decisions. As a result, family concealment of terminal diagnosis from patients, discussion of treatment without consulting patients’ wishes, and medical collusion in care decision-making are commonplace. Evidently, Living Matters is founded upon a socio-cultural system that contradicts the aspiring ACP philosophies of patient autonomy and self-determination.

ACP coordination

The second major theme category, “ACP Coordination”, illuminates the groundwork that had been carried out to establish the knowledge and relational foundation for launching ACP in Singapore's public healthcare sector (see Box 2). Stakeholders from all four groups agreed that “institutional leadership“ (theme 5), particularly from senior management of individual hospitals and specialist centers, was a key determinant for translating policy to practice. Many participants believed that without leadership activism, such as the establishment of new ACP mission statements from chief executives and medical directors, ACP promotional talks delivered by senior staff members, as well as ACP advocacy campaigns in public institutional spaces, programme awareness, and recognition among medical workers would be difficult to achieve. With such successful advocacy efforts, “programme receptiveness” (theme 6) was largely positive. Many participants expressed a strong endorsement of ACP's conceptual underpinnings which aim to elevate patients’ autonomy and dignity. Some participants further commended Living Matters for its ability to crystalize the informal practice of end-of-life care discussions into the wider service provision structure of the medical establishment.

Box 2. ACP Coordination

Theme-5: Institutional Leadership

“From our senior management's point of view, we have been quite active… We're spending a lot of time on ACP… So I think it ultimately boils down to the management itself, and how the government believes in this.” (Doctor, Female)

“When it comes from top down, generally more people will get the buy-in and be more ready to cooperate…. If you don't have the support from the senior management then I think that will be very tough.” (MSW, Female)

Theme-6: Programme Receptiveness

“I think bringing in ACP is really good… It starts patients thinking, and in general for everyone to think for their future - how would they want to be cared for?” (Nurse, Female)

“I think long before ACP was formalized, we had unconsciously already been practicing it… I had already tried to train my junior doctors in my place of work.” (Doctor, Female)

Theme-7: Interdisciplinary Trust

“Some of our ACP facilitators are not social workers, neither are they nurses you know… They have completely no experience with medical or healthcare related work. And they are doing ACP.” (Doctor, Female)

“Of course we are very angry… We are going to be the ACP facilitators… But sometimes doctors are not going to listen to us, because we are not doctors.” (MSW, Male)

Theme-8: Preparatory Training

“I was trying to role-play a session, so I was just going with the flow of the patient. I remember somebody told me, ‘You can't do that, you need to follow the questions by order… You have to follow the structure’. So I was quite taken aback.” (MSW, Male)

“I can say that the course (ACP Training) is a lot of theory and concept. But for us to go out on the ground, there is a need for a lot of practice and experiences… My first facilitation was a total disaster. I blank out, (I was) tongue tied, (I) couldn't follow the worksheet.” (ACP Facilitator, Female)

Despite support from the ground, the coordination and penetration of ACP were, nonetheless, hindered by the prevailing health system hierarchy. Particularly, “interdisciplinary trust” (theme 7) was a hurdle for buy-in among certain medical disciplines driven by a deep-rooted curative ideology. For instance, participants shared that surgeons generally do not believe they have a role to play in ACP as patients would not die in their wards or their operation theater. Lack of support from such physician groups as well as middle-management in turn impeded nurses’ and social workers’ ability to conduct ACP, as they lacked the authority to help patients with care decision-making without approval from attending physicians. Participants also reported that despite enhanced awareness, misconceptions of ACP as a form of euthanasia or discharge planning were commonly found among acute care personnel. These misconceptions fueled further resistance for fear of misuse. Under this atmosphere, large-scale “preparatory training” (themes 8) was carried out to cultivate a greater understanding of the Living Matters initiative, with an overarching objective to train all health and social care workers to act as ACP facilitators when called upon. Such training consisted of a one-day course that featured rote learning of salient palliative care options and medical procedures, as well as a highly scripted role play for practicing ACP conversations. Many participants shared that the training placed little emphasis on developing the interpersonal skills and emotional competence required to conduct a real-life end-of-life care discussion. As a result, some stakeholders, despite having graduated from training, do not feel comfortable or emotionally ready to render ACP.

ACP administration

The third major theme category, “ACP Administration”, outlines the dynamic processes in ACP provision experienced by the four stakeholder groups (see Box 3). Study participants expressed that Living Matters was implemented in stepwise phases with an initial focus on PPC-ACP that targets terminally ill patients and their families. Individual hospitals took on this task at their own pace and with different appointed programme leaders. As such, the administration of ACP evolved organically based on the unique organizational, clinical, and operational contexts within each setting, resulting in substantial “practice diversity” (theme 9). Participants agreed that there were three general ACP practice models. The first practice model encompasses a hospital-wide medical approach led by senior physicians with the expectation that all trained members of staff would conduct ACP with the support of ACP coordinators. A second model entails a disciplinary-base medical approach led by physicians who assign ACP coordinators to specific medical disciplines to carry out ACP and follow-ups. A third model comprises a social care model led by medical social workers supported by ACP coordinators that focus on training and medical disciplinary outreach, however, resulting with infrequent ACP provision.

Box 3. ACP Administration

Theme-9: Practice Diversity

“We do have a unique ACP clinic run by doctors, the junior doctors. We also do make-shift clinics (which are) run by the sisters, nurses, and social workers.” (Doctor, Female)

“Usually (it) is the MSWs, we also have coordinators doing it. The doctors do refer but their roles kind of end there.” (Medical Social Worker, Female)

“We have very few doctors’ referral basically. It is mainly the two of us, we go to the ward and screen the patients.” (ACP Coordinator, Female)

Theme-10: Workflow

“We used the ‘surprise question’… And then talked to the family of the patient to see if they were okay if we had a facilitator to come and talk to them.” (Doctor, Female)

“A lot of times, they (patients) are not ready for it, and if they are not too sure what this ACP thing is, the whole conversation will be off to a bad start.” (ACP Coordinator, Female)

“They try to catch them during their medical appointments… They may not want to talk about it, they are still not ready. So they just have to postpone, postpone, postpone.” (MSW, Male)

Theme-11: Operation Clarity

“As an MSW, you are expected to do a lot of things. So ACP is another thing we are sort of designated to do.” (Medical Social Worker, Female)

“To do the ACP discussion, we need to have allocated time… Tou have to spend time with the patient… Then a lot of things get held back.” (Nurse, Female)

“We have problems with Tamil speaking patients, because we don't have any Tamil colleagues at all… So that's always the losing group.” (ACP Coordinator, Female)

While models of practice are diverse, participants also highlighted that ACP was generally conducted via a three-step “workflow” (theme 10). First, healthcare staff intuitively evaluated patients’ readiness to confront mortality by appraising their physical status, death acceptance, and willingness to engage in end-of-life discussion without a standardized procedure. Second, upon receiving readiness assessment recommendations, physicians follow through with a surprise question criterion based on their professional expertise that roughly estimates whether a patient would die in the coming 12 months. If the prognosis is less than 12 months, a formal ACP referral is made to trained facilitators. Third, upon referral, appointments are scheduled with patients and their appointed family caregivers to begin the process of ACP conversations. These conversations are rarely conducted by an interdisciplinary team, consequently leaving social work and allied health workers feeling inadequate to explain complex medical procedures, and physicians feeling unprepared to deal with the socio-emotional needs of patients and families. With vast variations in clinical practice and uncertainties in workflow, “operation clarity” (theme 11) of the Living Matters programme emerged as a major appeal for all participants. The many feasibility challenges, such as role diffusion, limited manpower, added workload, unprotected time for ACP conversations, language barriers with ethnically diverse patients, and the tedious and time-consuming task of ACP paper documentation and subsequent electronic data entry into the national IT system, need to be resolved and improved so as to motivate and sustain stakeholders’ continuous interests and involvements in ACP.

ACP outcomes

The fourth major theme category, “ACP Outcomes”, describes the multiple layers of decision-making, expectation, and consequences of ACP as observed by the four stakeholder groups (see Box 4). Participants reported that patients’ “care preferences” (theme 12) are mostly shaped by three primary drivers including: (a) age-related drivers, with older patients’ inclining towards comfort care while younger patients leaning towards aggressive treatments; (b) cultural-spiritual drivers, with Chinese-Christian patients preferring more aggressive treatments due to their belief in miracles while Malay-Muslim patients likely choosing comfort measures with their trust in God's plan; and (c) family drivers, which insinuates the time, finance, and capacity resources that families have in meeting patients’ wishes in end-of-life care. According to many participants, family drivers can sometimes create discrepancies between expectations and realities of care, hampering concordance between preferences and outcomes. For instance, patients’ desire to be cared for and die at home are often curbed by families’ inability to fund the expenses associated with home care. Even if finances does not prove an issue and family carers are willing to maintain patients at home, it is far too common for them to hastily return their loved ones to the hospital during the final phases of life, as they are simply not emotionally prepared to deal with the psycho-socio-spiritual pain of dying.

Box 4. ACP Outcomes

Theme-12: Care Preferences

“The very old ones (patients) would like to have comfort care. But the younger ones who want to have a try opt for a trial.” (MSW, Female)

“I find Muslims generally more accepting (of ACP). They can accept what is given to them by God. I find Christians the most un-accepting because there is this element of miracle. So I find religion plays a part, age plays a part.” (Doctor, Female)

Theme-13: Medical-Social Dissonance

“This is his (patient's) wish, he still wants treatment… But the doctor says I am not going to sign that.” (ACP Coordinator, Female)

“When I saw the ACP Document, I was very uncomfortable. Because a lot of communication needs to happen before signing the document, but I don't think it is very evident.” (MSW, Male)

Theme-14: Performance Measurement

“We help the family to formulate their wishes - to actually organize their thoughts… We hope that there will be the best outcome for them, and (ACP is) not about our KPIs. Not about the numbers.” (Nurse, Female)

“ACP conversations may not be quantified through numbers… The old way of evaluating effectiveness through numbers discounts a lot of work that we are doing.” (MSW, Female)

Theme-15: Intrinsic Value

“I thought this (ACP) was very proactive, very humane, and very respectful of the person… It empowers the patient, the individual, their loved ones and family… As well, it's very empowering for the healthcare team.” (Doctors, Female)

“It (ACP) is about being heard, and that is very aligned with social work practices. It enables the patient's right and self-determination.” (MSW, Female)

Medical-social dissonance (theme 13) inherent in the existent health system hierarchy also poses threats to programme fidelity. Stakeholders in the nursing, social work, and allied health groups reported situations where physicians declined to endorse completed ACP documents as they were concerned by or opposed to care preferences made by patients and opined that patients did not fully understand their illnesses and were therefore not acting in their own best interests. An additional ideological clash between ACP and the conventional practices of the medical establishment is “performance measurement” (theme 14). Consensus from all participants revealed that the current scope of key performance indicators (KPIs), that only involve the statistics of completed and signed ACP documents, may transform the Living Matters programme into a check-box exercise, one that does not take into account the time and effort spent advocating and working with patients and families who may not choose to sign the documents after multiple discussions. Despite such shared frustration, every participant agreed that ACP holds many intrinsic values (theme 15) that statistical assessments cannot adequately capture. Particularly, it was believed that ACP provides patients with a safe platform to express their values and wishes to their families and professional care team, one that may not otherwise be available in a cultural climate of death avoidance and fear. ACP further serves to elevate patients’ autonomy, involve families as partners of care, and provide healthcare workers with a holistic understanding of their charges as people instead of a body comprising of symptoms and illnesses.

Sustainability shift

The fifth and final major theme category, “Sustainability Shift”, encapsulates the ideas and aspirations shared by all four stakeholder groups in ensuring the healthy and continuous development of ACP in Singapore (see Box 5). Participants contended that the sustainability of Living Matters could be enhanced by addressing the prevailing negative socio-cultural norms and longstanding local death taboos. The suggested action involves a multipronged public health model for ACP.

Box 5. Sustainability Shift

Theme-16: Public Life and Death Education

“I think it is education. You need to start, not only at the hospital level, but with education of the whole country. Students, residents, residency programs, all the healthcare nursing courses, let talk about (death), let's have a module to explain what it is about.” (Medical Social Workers, Female)

“I think make it (ACP) more visible to society…TV for the older ones like my parents… Movies, adverts, social media for the younger ones, roadshow, campaigns, marathons, religious events.” (Doctor, Female)

Theme-17: Targeted Holistic EoL Care Training

“I will make it part of medical school so that it is ingrained in them (students), to cure is as important as to comfort… But not many are taught in comfort, 90% of our curriculum is on cure.” (Doctor, Female)

“We definitely need refreshers and a lot of open dialogs to share… To have more open dialogs and to throw their challenges out there and learn from one another. I think it has to be ongoing training rather than one off.” (Medical Social Worker, Female)

Theme-18: Governance and Service Alignment

“Right now it's all done by AIC and we're on the side-line like a peripheral and trying to go in. If MOH accepts ACP as part of (patient) care, then I think it will make things a lot easier and more receptive.”(Medical Social Worker, Female)

“I think it is very important that the government leads the drive… People are social creatures, so if it is a national activity, then chances are the success rate will take care of itself.” (ACP Coordinator, Female)

Theme-19: Empowered Citizenry

“If you talk about the elderly population, you might think that they don't feel confident having a conversation about their care with the doctors. But with the younger, the more educated population, maybe the 40 s or 50s… How can we help them to understand more such that they know that they have a part to play?” (Medical Social Worker, Female)

“It's not just one awareness day for ACP, but every day is an awareness day… You put it into people's conversation, then gradually, I think people will start to open up.” (Nurses, Female)

The first prong would encompass an ecological “public life and death education” (theme 16) programme with both formal and informal learning for all members of society. This would include structured life and death education curricula in secondary schools, colleges, universities, and especially medical, nursing, and social work institutions, as well as sustainable awareness campaigns on life and mortality. A second prong would involve the development and provision of “holistic end-of-life training” (theme 17) that targets existing medical, health, and allied health workers who are passionate in caring for patients and families facing critical illness and death, rather than a one-size-fits-all programme. A third prong would comprise “governance and service alignment” (theme 18) to better connect and facilitate inter-agency and interdisciplinary collaboration between government ministries, healthcare institutions, medical, and social care professionals. It is believed that such a public health model for ACP would ultimately create an “empowered citizenry” (theme 19); one that will not desolately assume the role of a sick patient in the face of illness but become more responsibly informed and engaged in the active participation, management, and governance of their own health and mortality.

Discussion

Principle findings

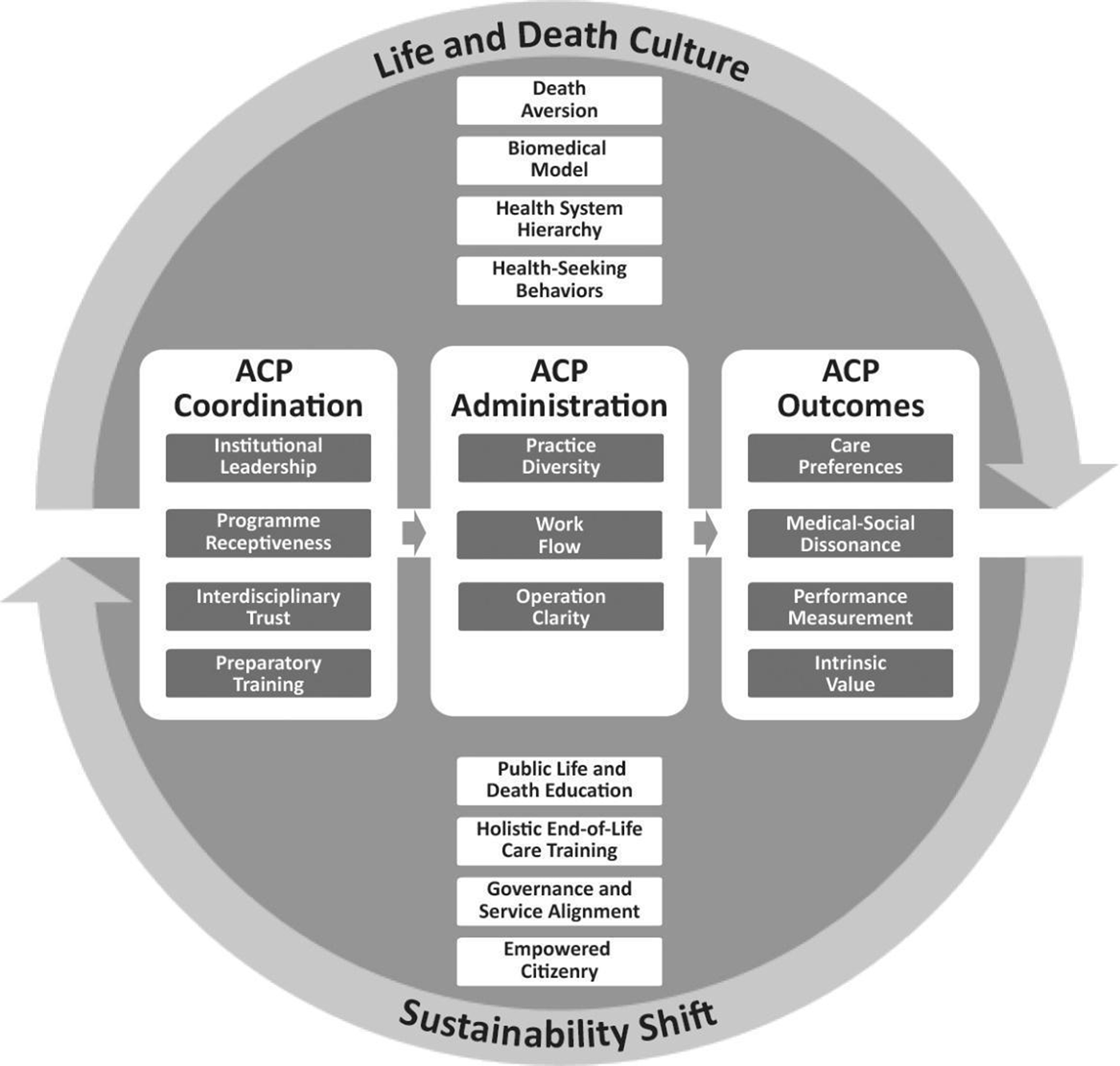

This is the first study that systematically examined the developmental underpinnings of Singapore's national ACP initiative and critically investigated the dynamics, mechanisms, and socio-systemic factors that influence ACP implementation in the context of Asia. By adopting an interpretive-systemic framework of inquiry that elicited experiential narratives and multiple interpretations from 63 participants of 4 key stakeholder groups involved in the Living Matters programme, 19 themes emerged to elucidate the system dynamics that underpin the implementation challenges and successes of ACP in the Asian context. These 19 themes are organized into 5 major theme categories to form an interpretive-systemic framework (ISF) for sustainable implementation of ACP. The ISF-ACP reflects the social, cultural, political, operational, and spiritual contexts that support national ACP development and highlights the importance of health policy, organizational structure, social discourse, and shared meaning in the planning and delivery of palliative care services for aiding end-of-life care decision-making (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Interpretive-systemic framework for sustainable advance care planning.

Our findings reveal that ACP is a welcome initiative and an important addition to Singapore's palliative care ecosystem. Most health and social care professionals interviewed believed in its capacity to help patients and families explore and express their needs and concerns at the end-of-life, as well as to make informed care decisions for enhancing autonomy and potentiality improving concordance between care preferences and outcomes. However, ACP was established in an Asian society deeply rooted in a Confucian heritage culture which comprises of a longstanding history of death aversion, with a firm belief in death pollution whereby the bad aura of the dead is deemed contaminating and can negatively affect the lives of the living (Ho and Chan, Reference Ho, Chan and Conway2011). Hence, to openly discuss death-related issues is considered a threat to social and relational harmony under the Confucian cosmology, as Confucius himself had famously stated “We do not yet know life, how do we know death?” (Confucius, 1997, 11:11) to stop his disciple's query on mortality. Similar traditional beliefs on propriety and filial piety have greatly influenced the Asian way of life. Therefore, it is not surprising that much hesitation about ACP exists among the Singaporean public, with only 10,000 people completing the initiative since its 2011 inauguration (Foo, Reference Foo2017). ACP requires individuals to talk about the taboo of death with their loved ones, and especially their family elders, which can be deemed disrespectful and even unfilial.

Our findings further show that the current generation of older Singaporeans is often reluctant to make their own healthcare decisions and rely heavily on their families and their adult children for such tasks. This may well reflect an enduring collectivistic culture among Asian populations, pointing towards the need to move beyond the notions of autonomy and patient-centered care which dominates the Western healthcare paradigm in the twenty-first century (Chouchane et al., Reference Chouchane, Mamtani and Dallol2011), to that of family-centered patient care with greater recognition and appreciation of family interdependence and involvement in healthcare decision-making (Ho and Tan-Ho, Reference Ho and Tan-Ho2016). Paradoxically, while ACP is grounded on a holistic view on health, we found that current healthcare practices in Singapore are still driven by the traditional biomedical model that focuses predominantly on sustaining and prolonging life (Illich, Reference Illich1976), deeming palliative and supportive care a secondary priority. This, together with a healthcare education curricula that also emphasize curation over palliation, limited life and death education (Dickinson, Reference Dickinson2006) which perpetuates a death-denying ethos in medicine, have all consolidated to create systemic challenges and competing interests that have hindered ACP implementation.

Under a socio-cultural backdrop of death aversion and biomedicine practices, doctors and clinicians often feel compelled to prescribe aggressive treatments and are reluctant in referring patients to palliative care or engaging them in end-of-life care conversations. Despite strong leadership advocacy in pushing forth the agenda and ideals of ACP, the challenges faced in unifying operational and referral procedures, together with constraints in manpower and resource support, have greatly hampered the delivery of ACP. To resolve these difficulties, our participants believe that a clearly defined service agenda that integrates a standardized approach to ACP provision with better supportive structures can strengthen the foundational bedrock of improving palliative care and enhancing quality of death. A holistic training programme that imparts cognitive knowledge, cultivates emotional competence, and instils interpersonal skills for working through the demanding issues of mortality among all health and social care workers can also empower them to better support the dying and the bereaved. Furthermore, a formal life and death education curricula that target students of colleges and universities, particularly those enrolled in medicine, nursing, social work, and allied health programmes, can nurture their empathic understanding of and practical competence for working with illness, death, and loss. Finally, a concerted and sustained publicity campaign to promote open dialogue on mortality can foster greater awareness and acceptance of ACP in Singapore.

All of these recommendations on programme sustainability, particularly those related to formal and informal education, are indeed feasible for reducing and even eradicating the longstanding taboo on death in Asia (Ho and Chan, Reference Ho, Chan and Conway2011). It, however, requires a paradigm shift in societal attitudes and perceptions toward mortality made possible through a Public Health Strategy that promotes awareness, acceptance, knowledge, and understanding of palliative care into all levels of society (De Lima and Pastrana, Reference De Lima and Pastrana2016).

Practice and policy implications

The implementation challenges of ACP identified in our study, while seemingly impenetrable, are not unresolvable. Applying a public health strategy (PHS) to integrate palliative care into all levels of society would facilitate greater recognition and acceptance of the ACP for supporting health and illness; and such a strategy would necessitate bilateral involvement of top-down approaches from the public policy level, as well as a bottom-up approach from the community level. First, palliative care needs to be incorporated into the many layers of the public medical system, as well as the greater social welfare system, involving all professional and societal members through collective social action and government leadership (Higginson and Koffman, Reference Higginson and Koffman2005).

Second, ACP advocates need to interact with policy makers, health care professionals, as well as the general public on a consistent basis, starting with the introductory work of education on death, dying, bereavement, hospice, and palliative care service availability, and advance care planning. Education and advocacy that lead to real social change must further be supported and informed by ongoing institutional and community-based research that elicits the specific needs of palliative care professionals, as well as the concerns of dying patients and their families at the end-of-life, with a sensitivity that recognizes the assumptions, positions, references, values, and beliefs of the local culture (Stjernswärd et al., Reference Stjernswärd, Foley and Ferris2007). Such a PHS will empower individuals to become active participants in the governance of mortality, can engage the community in end-of-life care programme planning, and aligns palliative service provision with existing health care systems and social support networks (Meier and Beresford, Reference Meier and Beresford2007).

Ultimately, in order to push forth the aspiration of accessible and effective ACP for all, there needs to be a common discourse shared among all stakeholders of a healthcare system; one that penetrates every layer of social structure and boundary within a society. Such a discourse can be achieved through “Health Promoting Palliative Care”, which translates the hospice ideals of whole-person care into broader public languages and practices related to prevention, harm reduction, support, education, and community actions (Kellehear, Reference Kellehear1999). The notions of “compassion” and “universality of death and loss” then become the impetus for driving public discourse to facilitate and encourage individuals, groups, and communities to discuss, assess, and develop strategies in addressing their perceived needs at the end-of-life (Kellehear, Reference Kellehear2005).

Strengths and limitations

While most qualitative research makes no claim for generalizability, the methodology employed in this study ensured perspective inclusivity from all professional stakeholders of Singapore's national ACP programme across the entire nation state. Furthermore, the systemic and systematic processes of inquiry enabled the research team to capture a comprehensive overview of the development of ACP at the macro-national level, acquire multiple interpretations of ACP implementation at the meso-institutional level, and generate idiosyncratic elucidation of ACP provision at the micro-individual level. In terms of data analysis, while framework analysis was adopted with emphasis on a deductive approach, a concurrent inductive approach was also employed for constant comparisons of findings leading to model development; hence, the results generated from this study and its interpretations were derived from the data, as well as informed by a pre-existing framework. Nonetheless, future research can consider employing a more inductive analytical approach to reveal a deeper range of narratives, experiences, and realities. Overall, the current findings can provide moderatum generalizability (Williams, Reference Williams and May2002) which allow for interpreting structures and understanding processes that are applicable in similar settings, with similar populations, as well as in theory building. As such, the results and conceptual framework generated from this study can competently serve to guide and inform other Asian regions, many that share similar social and cultural contexts such as those of Singapore, in developing their own ACP programmes. Future research can further strengthen this body of knowledge by examining the lived experience of ACP engagements and outcomes among Asian patients and families.

Conclusion

ACP has become a critical component of quality palliative care in most advanced societies around the world, but it is vastly underdeveloped in many parts of Asia. The current research provides valuable insights on the developmental challenges and implementation outcomes of the first national ACP programme from the region. Its findings are relevant to the whole of Asia for enhancing palliative care provision and for informing the development of comprehensive and appropriate ACP programmes to empower patients’ autonomy and dignity in the face of loss and mortality.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: A.H.Y.H. and P.L. conceived and designed the study, collected, analyzed, interpreted the data, drafted and revised the article. W.S.P., C.K.L., and J.C. conceived the study, obtained funding, audited the data, and revised the article. W.S.T., P.V.P., L.H.W., and O.D. collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and revised the article. All authors gave final approval of the revision to be published. A.H.Y.H. is the guarantor.

Funding

This study is funded by the Agency for Integrated Care Singapore, which receives public funding from the Ministry of Health of the Singaporean Government. The funder has played no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data sharing

No additional data available.