Introduction

For patients with incurable diseases, unbearable symptoms that are either physical (e.g., pain or dyspnea) or psychological or existential (e.g., psychic distress or death anxiety) profoundly impair quality of life. In this context, palliative sedation is widely practiced to relieve intolerable suffering from refractory symptoms. Nevertheless, in spite of clear guidelines, there is still substantial variation by country in end-of-life care sedation practice. In European countries (e.g. the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands), cultural and ethical perspectives on this topic can modulate current practices: low sedation in the United Kingdom and deep sedation for Belgium and the Netherlands, as an alternative to euthanasia which is allowed in these two latter countries (Seymour et al., Reference Seymour, Rietjens and Bruinsma2015). Even among international guidelines provided by the American Academy of Hospice and palliative Medicine, the European Association for Palliative Care (Gurschick et al., Reference Gurschick, Mayer and Hanson2015) or the Canadian Society for Palliative Care Physicians (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Cellarius and Henry2012), variations exist regarding definitions of terminology, practice, indications for its use, medications used, and timing of implementation.

Continuous deep sedation until death (CDSUD) is a practice already applied in some European countries such as Belgium (Anquinet et al., Reference Anquinet, Rietjens and Seale2012; Robijn et al., Reference Robijn, Cohen and Rietjens2016), the United Kingdom (Seale, Reference Seale2010), Denmark, Holland, Italy, and Sweden (Miccinesi et al., Reference Miccinesi, Rietjens and Deliens2006). Nevertheless, France is the first country around the world that has legislations on CDSUD (Aubry, Reference Aubry2017). Indeed, since the Claeys-Leonetti law (February 2016), patients in France can request healthcare professionals to implementCDSUD to alleviate their suffering. This procedure is strictly reserved for patients whose impending deaths are expected within a few hours to a few days (www.legifrancegouvfr, 2016). Sedation protocol causes unconsciousness until death occurs. It is strictly monitored and considered a last resort option for managing intractable terminal suffering (Cherny et al., Reference Cherny2014). It might be referred to as the “French exception” because patients have a right to request CDSUD, making it a sui generis end-of-life practice (Horn, Reference Horn2018; Aubry, Reference Aubry2017).

Under French law, refractory psycho-existential distress of end-of-life patients as well as their physical suffering can be relieved by CDSUD. However, the process and the method of diagnosing and measuring the extent of the refractory nature of psycho-existential distress are controversial and challenging. This paper is a narrative survey of the use of CDSUD in palliative care in France. It will mainly focus how it can be differentiated from euthanasia and by identifying and assessing refractory psycho-existential distress. It offers guidance for interpreting patient requests for CDSUD from a psychological and psychopathological perspective and therefore will help for appropriate implementation of this law.

Search method

In this narrative review, articles, mainly in English, and guidelines in French published between 2000 and 2019 reporting on current practices implementing CDSUD were examined.

We differentiated articles published before 2016, mainly in Anglo-Saxon countries, from French articles published after 2016, reporting CDSUD practice under the Claeys-Leonetti law.

The data were derived from the PubMed full-text archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature, using the following keywords: palliative sedation, CDSUD, psychological distress, and existential distress. We selected mainly those focusing on French experience (often case reports) and confronted them to American and Canadian palliative sedation reviews. We added recent review articles related with demoralization syndrome and desire to hasten death to help us to discuss differential diagnoses in front of CDSUD request for refractory psycho-existential distress.

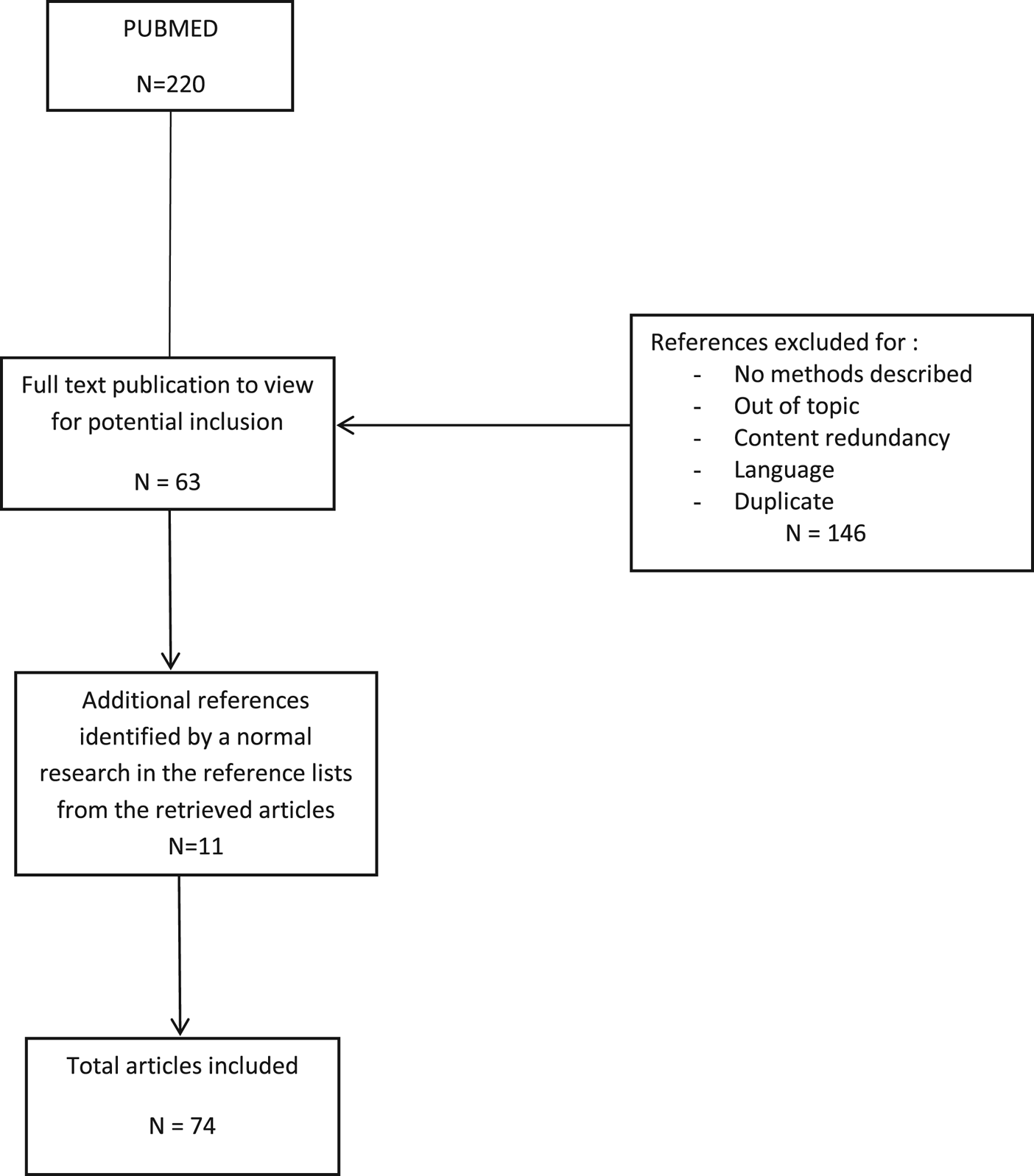

Figure 1 summarizes the flow chart of the literature selection process for the present article.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the literature selection process.

Results

The complexity of the issues about CDSUD was interpreted using the following defined concepts.

Refractory symptom

The French National Authority for Health (HAS: “Haute Autorité de Santé”) defines a symptom as “refractory” when it fulfills all five of the following criteria (Haute Autorité de Santé, 2018).

• The patient perceives it as unbearable.

• All available and adapted therapeutic means have been proposed and/or implemented.

• Therapeutic efforts are not effective within a period acceptable to the patient.

• The patient is not experiencing the treatment's expected extent of relief.

• The patient is experiencing significant side effects, including impaired alertness and quality of life.

These criteria are similar to American and Canadian criteria: a refractory symptom is defined as “any symptom whose perception is unbearable and cannot be relieved despite obstinate and aggressive efforts to find a suitable therapeutic protocol without compromising patients consciousness” (Cherny and Portenoy, Reference Cherny and Portenoy1994).

Refractory psychological or existential distress

Refractory psychological or existential distress should be considered from a global perspective that includes the physical symptoms potentially distorting a professional assessment of the refractory nature of the distress, particularly regarding incurable diseases under palliative care. Nevertheless, psychological distress could relate to other psychopathological or psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety or depressive disorders or delirium, that can be diagnosed using objective criteria and treated with pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic treatments.

Existential distress at the end of life includes loss of personal meaning and purpose to life, fear of death, despair, anguish, hopelessness, a sense of burdening others, a sense of isolation, loss of dignity, helplessness, and betrayal (Henoch and Danielson, Reference Henoch and Danielson2009). Patients tend to want answers to or reasons for unresolved concerns, and they ask questions, such as “why me?” or “why am I here?” or “what is the meaning of my life?” (Bruce and Boston, Reference Bruce and Boston2011). Existential distress refers to a system of thoughts or values that are subjective, personal, and cannot easily be treated by the usual therapeutics. Therefore, in clinical practice and from our experience, precisely defining psycho-existential distress as refractory remains challenging or impossible.

Consequently, it is not surprising that the French Society of Palliative Care (SFAP: Société française d'accompagnement et de soins palliatifs) and the Quebec College of Physicians (CMQ: Collège des médecins du Québec) recommended caution when assessing the refractory nature of existential distress. For the CMQ, a “well-managed multidimensional therapeutic approach (listening, spiritual and religious support, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, etc.) is needed that involves the contributions of several professionals” (www.cmq.org, 2016). The SFAP emphasizes avoidance of vague terms that do not define or describe specific syndromes or diagnoses (www.sfap.org, 2014). SFAP pointed out two major types of distress that tend to indicate intermittent or temporary sedation.

• Situations of dominantly existential refractory distress with a slowly evolving serious illness (e.g., neurodegenerative diseases and locked-in syndrome).

• Situations of predominantly psycho-existential distress manifested as requests for assisted suicide, euthanasia, or induced sleep (www.sfap.org, 2014).

Palliative sedation

The heterogeneity in the literature's terminology used to define and describe “palliative sedation” is problematic (Hallenbeck, Reference Hallenbeck2000; Claessens et al., Reference Claessens, Menten and Schotsmans2008; Twycross, Reference Twycross2019. A previous review indicated more than 50 definitions, such as palliative, terminal, continuous, controlled, and deep-sleep sedation (Papavasiliou et al., Reference Papavasiliou, Payne and Brearley2013). According to the European Association for Palliative Care, palliative sedation is solely used to treat refractory symptoms with intentional sedation either intermittently or temporarily or continuously for terminally ill patients usually until death (Abarshi et al., Reference Abarshi, Rietjens and Robijn2017). Palliative sedation has been defined as “the use of sedative medications to relieve intolerable and refractory distress by the reduction in patient consciousness” (Morita et al., Reference Morita, Tsuneto and Shima2002). Palliative sedation must fulfill the following three criteria (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Cellarius and Henry2012).

• It uses pharmacological agents to reduce consciousness.

• It is used only in cases of intolerable and refractory symptoms.

• It is used only for patients with advanced and incurable illnesses.

From an ethical perspective, sedating a patient suffering from refractory symptoms in the final days of life until death could be used to relieve symptoms with no intention to hasten or cause death (Hallenbeck, Reference Hallenbeck2000; Claessens et al., Reference Claessens, Menten and Schotsmans2008). The purpose would be to decrease or eliminate the patient's perception that the situation and/or symptom(s) are unbearable when all other means available and adapted to meet the situation have been proposed and/or implemented without providing the intended relief (www.has-sante.fr, 2018). Supporters assert that palliative sedation should be an optional intervention and its affects should be carefully monitored and documented (De Graeff and Dean, Reference De Graeff and Dean2007). They point out that, when appropriately indicated and correctly applied, it has no apparent detrimental influences on survival, and it should be considered part of the continuum of palliative care (Maltoni et al., Reference Maltoni, Scarpi and Rosati2012).

Palliative sedation is being used to relieve terminally ill patients' psycho-existential distress (excluding dementia) as well as their refractory physical suffering (Chater et al., Reference Chater, Viola and Paterson1998; Mercadante et al., Reference Mercadante, Intravaia and Villari2009; Maltoni et al., Reference Maltoni, Scarpi and Nanni2014), which might include terminal delirium, particularly when it is accompanied by organic failure (Morita, Reference Morita2004). In particularly complex cases, the SFAP stipulations recommend that, when psycho-existential distress has become refractory to appropriate care in advanced and/or terminal cases, transient sedation may be implemented after repeated multidisciplinary evaluations have been performed, including psychological and/or psychiatric mental health assessments (www.sfap.org, 2014). SFAP specifies that the emotional, psychological, or existential distress experienced by family members or caregivers does not justify the use of deep sedation (www.sfap.org, 2014). Some authors apparently preferred to use the term “continuous deep sedation” or “continuous sedation until death” rather than “palliative sedation” because palliative sedation is not necessarily continuous or deep (Twycross, Reference Twycross2019).

Continuous deep sedation until death

Under the Claeys-Leonetti law, CDSUD consists of delivering a sedative (usually midazolam) that leads to a profound and continuous change of consciousness until death. It is associated with analgesic treatment (opioids) and the cessation of all life-sustaining therapeutics, including artificial nutrition and hydration (De Nonneville et al., Reference De Nonneville, Marin and Chabal2016). CDSUD can be implemented after a patient's request when she or he meets one of the following three criteria (www.legifrancegouvfr, 2016).

• A vital prognosis is engaged in the short term while optimal treatment of refractory suffering is being experienced.

• The patient is confronting a serious and incurable medical condition, he or she has decided to stop medical treatment, the decision to stop treatment is life-threatening in the short term, and unbearable suffering would likely ensue.

• When the patient is unable to express his wish and when the practitioner following a collegial procedure decides to stop life maintaining treatment including artificial nutrition and hydration, to respect patient's refusal of continuing treatments considered as unreasonable.

Moreover, the HAS guidelines regarding CDSUD are clear (www.has-sante.fr, 2018).

• The case must meet the five criteria defining a symptom as “refractory.”

• Multidimensional systematic evaluations must be performed to assess global suffering.

• Repeated multidisciplinary assessments must be performed, including assessments by psychologists or psychiatrists.

• All relevant therapeutic approaches must previously have been taken regarding physical, psycho-existential (including listening, psychotherapy, body mediation therapy, and pharmacotherapy), and, when indicated, spiritual symptoms.

Because euthanasia is defined as a homicide under French law, CDSUD must clearly be distinguished from euthanasia, and the HAS distinguishes them from each other in five ways (Table 1) (www.has-sante.fr, 2018). Consequently, before implementing CDSUD, a clinician must prove that all available and adapted therapeutic options have been tried, there is an observable lack of the relief expected by the patient (including an unacceptable delay in the desired therapeutic effects), and intolerable side effects. Last, the decision to implement CDSUD for end-of-life patients must be undertaken only after collective deliberations that include the patient's managing physician, multidisciplinary healthcare team, and a consulting doctor with no hierarchical link to the managing physician. The patient's managing physician makes the final decision.

Table 1. Differences between deep continuous sedation and euthanasia (adapted from HAS guidelines, Haute Autorité de Santé, 2018) (with permission)

Other diagnoses of psycho-existential distress

During clinical assessments of refractory psycho-existential symptoms, clinicians must remember that patients tend to have uncertain or vague realistic expectations for speedy CDSUD implementation. Thus, clinicians should consider other psychological problems, such as demoralization syndrome, depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, desire to hasten death, and a desire for assisted suicide or euthanasia. In France, demoralization syndrome and desire to hasten death are emphasized because physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia are illegal.

Alternative diagnoses

Demoralization syndrome

Demoralization syndrome has been studied for decades in patients with chronic physical illnesses, such as advanced cancers (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Clarke and Street2001; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2015). Initially, the concept was proposed for application in palliative care because of its core characteristics of hopelessness, loss of personal meaning, and existential distress (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Clarke and Street2001). It is associated with disability, bodily disfigurement, fear of loss of dignity, social isolation, subjective sense of incompetence, feeling increasingly dependent on others, and/or self-perceptions as a burden (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Clarke and Street2001). In the context of palliative care, demoralization syndrome might include an expressed desire to die (Parker, Reference Parker2004).

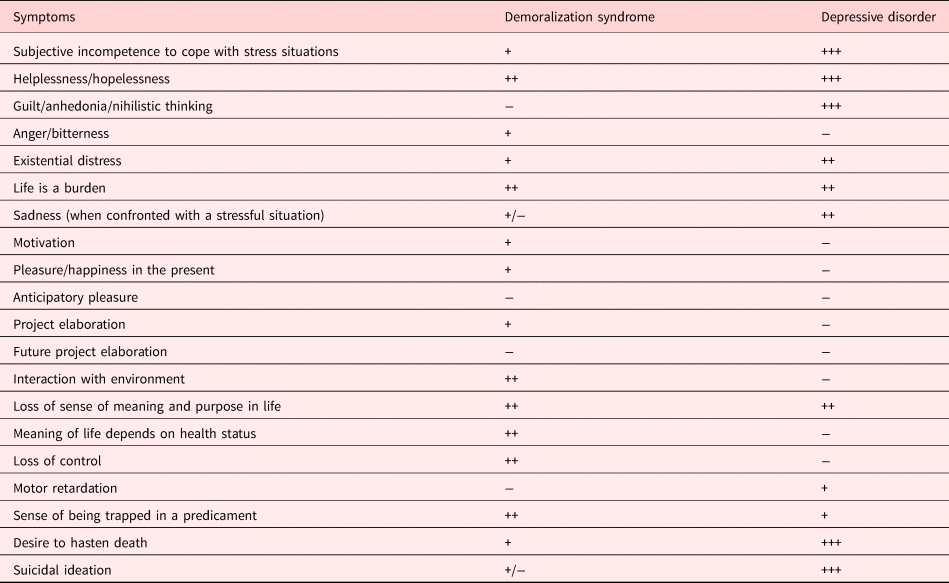

A German survey of 112 inpatients with various tumor sites in early and advanced disease stages found that a sense of loss of dignity explained the relationship between physical problems and demoralization in 81% of the cases and, conversely, demoralization mediated 53% of the relationship between physical problems and a sense of loss of dignity (Vehling and Mehnert, Reference Vehling and Mehnert2014). The researchers suggested a conceptual link exists between existential concerns (i.e., loss of dignity) and existential distress (i.e., demoralization). However, in a study of 2,295 cases, the prevalence of demoralization syndrome was reported in 21–25% of oncology patients (Vehling et al., Reference Vehling, Kissane and Lo2017;Nanni et al., Reference Nanni, Caruso and Travado2018) and in 13–18% of advanced cancer patients (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2015). Its prevalence in palliative care settings was reported by a Portuguese study at about 52.5%, although it used a small sample (80 cases) (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Nunes and Barbosa2016), and demoralization syndrome is often undiagnosed in terminally ill patients (Mogos et al., Reference Mogos, Roffey and Thangathurai2013). One reason for the lack of diagnoses is that, although it might be associated with depression, demoralization syndrome in oncology and palliative settings tends to be misdiagnosed as a depressive disorder (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Wang and Chou2015). Table 2 contrasts demoralization syndrome with depressive disorders regarding symptomatology, suggesting that correct diagnosis is sometimes difficult. In the Portuguese study, about 30% of the patients met the criteria for demoralization syndrome and for depression using the DSM-IV nosography (Julião et al, Reference Julião, Nunes and Barbosa2016). Some authors understood demoralization syndrome as equivalent to an adjustment disorder for patients coping with advanced cancer (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Bobevski and Gaitanis2017). Nevertheless, one paper pointed out that demoralization syndrome should be clearly distinguishable from the nosography of other mental disorders (Grassi and de Figueiredo, Reference Grassi and de Figueiredo2018) and personal characteristics, duration of symptoms and clinical interviews would likely help to make those distinctions.

Table 2. Differences between demoralization syndrome and depressive disorder in palliative care patients

“+” = possible, “++” = frequent, “+++” = very frequent, “−”= absence, “+/−”= possible or absent.

Desire to hasten death

Some incurably ill patients engage in interior monologues that include a desire to die, which might develop into a desire to hasten death (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Wilson and Enns1995). Statements that express a desire to die have three elements: (1) intentions that describe the person's desires when he or she expresses a desire to die, (2) overt and covert motives or reasons for wanting to die, and (3) social interactions that express and are understood as a desire to die (Ohnsorge et al., Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014). Although a patient might want to hasten death, she or he might not consider it an immediate possibility for moral, spiritual, or other reasons. Aside from suicide, CDSUD might be considered a possible way to accelerate the dying process. These patients also might consider hastening death as a moral and realistic present option even if they have not moved beyond the stage in which it is merely imagined and considered. These patients might explicitly request assistance to die or they might refuse life-sustaining support, such as food, drink, or medical treatment, with the intention of hastening their deaths (Ohnsorge et al., Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014).

Recently, an international body offered the following definition of the desire to hasten death as “a reaction to suffering, in the context of a life-threatening condition, from which the patient can see no way out other than to accelerate his or her death. This wish may be expressed spontaneously or after being asked about it, but it must be distinguished from the acceptance of impending death or from a wish to die naturally, although preferably sooner” (Balaguer et al., Reference Balaguer, Monforte-Royo and Porta-Sales2016). Considering this definition, it is not surprising that a desire to die or hasten death would occur in palliative settings (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Kristjanson and Ashby2006; Monforte-Royo et al., Reference Monforte-Royo, Villavicencio-Chavez and Tomas-Sabado2012) and that the desire would persist after a patient entered palliative care (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Artin and Person2004).

However, patients sometimes express a desire to die, but they do not desire to hasten death. Moreover, this desire (as an idea or imagined desire to die) must be distinguished from a determination related to actions intended to lead to death. Therefore, some patients express a desire to hasten death without acting on it, and other patients act on the desire to hasten death. Prevalence for desire to hasten death in palliative care is about 8.5–22.2% (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Wilson and Enns1995; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2000). A desire to hasten death might emerge as a reaction to refractory physical symptoms (e.g., pain or dyspnea), psychological symptoms (e.g., profound sadness, sense of little self-worth, hopelessness, fear, and so on), or existential symptoms (e.g., loss of meaning or loss of social usefulness) (Balaguer et al., Reference Balaguer, Monforte-Royo and Porta-Sales2016).

A French national-level cross-sectional study on requests to hasten death was conducted among 789 French palliative care organizations (Ferrand et al., Reference Ferrand, Dreyfus and Chastrusse2012). The request was mostly made by patients (61%), family members and close friends (33%), and nursing staff (6%). Symptoms conducive to the desire to hasten death were difficulty eating/feeding (65%), loss of autonomy and movement (54%), excretory problems (49%), cachexia (39%), anxiety-depressive states (31%), and uncontrolled pain (3.7%). Interesting, 79% of the requests did not include a physical reason for the request, and, whereas 37% of the requests to hasten death were maintained, 24% of them fluctuated despite regular follow-ups by a palliative care team. Doctors and nurses interpreted the requests as a desire for relief (69%), the patient's sense of his or her inextricable situation (44%), an actual desire to cease living (36%), or a desire to be helped to die (30%). The study pointed out that a desire to hasten death was often maintained despite adequate palliative care that acceptably controlled pain and the psychological support of mental health specialists (Ferrand et al., Reference Ferrand, Dreyfus and Chastrusse2012).

From a psychiatric perspective, it is important to identify all possible underlying depressive disorders, although a terminally ill patient's expressed desire to die might not relate to a depressive condition (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dalgleish and Chochinov2016). Moreover, a desire to hasten death must be distinguished from suicidal ideations. Patients might desire accelerated dying while they exclude suicide as an option (Ohnsorge et al., Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014a). A patient's willful acts toward achieving death through specific means are considered suicide attempts. Some studies have found that depression, loss of meaning and purpose, hopelessness, loss of control, and low self-worth were strong clinical markers of the desire to hasten death among advanced cancer patients (Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2000; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2017; Parpa et al., Reference Parpa, Tsilika and Galanos2019). However, these expressed desires might be interpreted as desires to limit treatment or desires to refuse life-sustaining treatments, expressions of anticipated death anxiety, or interest in discussing end-of-life concerns. A desire to hasten death might be an expression of a desire to escape a burdensome existence.

Sometimes, patients' desires to hasten death only occur during acute crises and express the hope that the dying process will be short. Understanding statements indicating a desire to hasten death helps healthcare practitioners to accurately know about patients' subjective experiences (Ohnsorge et al., Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014a). Thus, clinical determinants and meanings of patients' requests to hasten death should be investigated. Ohnsorge et al. (Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014b) developed a model for clinicians to use to improve their understanding of the meanings of their patients statements.

The impetus underlying a desire to die has three dimensions: motives/reasons, meanings, and functions. Reasons are patients' motives underlying the desire to die. These might be about physical symptoms, such as pain or dyspnea, or psychosocial-existential symptoms, such as anxiety, loneliness, meaninglessness, a sense of dependency, worries about future discomfort, and so on (Ohnsorge et al., Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014b; Morita et al., Reference Morita, Sakaguchi and Hirai2004).

Meanings describe the broad explanatory framework that explains what this desire means to the patient. The meaning of a desire to hasten death is related to the patient's personal values and moral beliefs. Ohnsorge developed a non-exhaustive list of following items as meanings of the desire to hasten death (Ohnsorge et al., Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014b).

• The patient wants to die or to control the time of death

• The patient wants to allow his or her end-of-life process to naturally progress

• The patient wants to use death to end her or his severe suffering

• The patient wants to end a situation perceived as unreasonably demanding

• The patient wants to spare others from being burdened by the patient

• The patient wants self-determination until the last moments of life

• The patient wants to end his or her life, which is now perceived as valueless

• The patient wants to move on to a different plane of existence

• The patient wants to be an example to others

• The patient does not want to wait for death

Functions describe the conscious and subconscious effects of a patient's desire to die on themselves and/or others. The four functions are (1) a cry or appeal for help to others to maintain interpersonal interaction or dialogue, (2) a way that patients can talk about dying, (3) a way to re-establish the patient's perceived loss of personal agency, and (4) a way to get attention from doctors and nurses.

Patients' reasons for desiring to die could be investigated regarding the following areas: (1) adequacy of symptom control; (2) difficulties in the patient's relationships with family members, friends, and doctors and nurses; (3) psycho-existential disturbances, such as grief and depressive or anxiety disorders; (4) organic mental disorders; (5) personality disorders, and (6) personal philosophical, religious, and spiritual orientations to the meaning of life and suffering (Block and Billings, Reference Block and Billings1994).

A desire to hasten death, which might or might not be an actual request to die, might continue to fluctuate at the end of life and be influenced by factors under the control of the palliative care team (Goelitz, Reference Goelitz2003). The request might be a desperate coping tactic for maintaining control over anticipated agony, and caregivers should not necessarily interpret these statements as actual requests or demands to hasten death (Pestinger et al., Reference Pestinger, Stiel and Elsner2015). Thus, the request to die could be a dynamic, ambivalent, and interactive process that changes over time and with varying circumstances. Whether a request is flexible or rigid tends to depend on an internal progression in the patient's thought process, the progress of the disease, and/or applied treatments (Ohnsorge et al., Reference Ohnsorge, Gudat and Rehmann-Sutter2014a). Despite the flexibility and responsiveness of desires to die related to the patient's context, several factors have predicted the desire to hasten death in about two-thirds of cases reported through literature (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Wilson and Enns1995; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2000; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Burnett and Pelusi2002; Pesin et al., Reference Pessin, Rosenfeld and Burton2003; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2017).

• The sense of a poor or very poor quality of life (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2017)

• Observed depressive symptoms (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Wilson and Enns1995; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2000)

• The sense of meaninglessness, purposelessness, demoralization, and/or hopelessness (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Burnett and Pelusi2002)

• The sense of loss of control (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2017)

• The sense of low self-worth (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2017)

• Cognitive impairment (Pesin et al., Reference Pessin, Rosenfeld and Burton2003)

Discussion

(CDSUD for patients who are terminally ill with refractory psycho-existential distress is complex, controversial, and the palliative care community has not reached consensus (Sadler, Reference Sadler2012) The validity of CDSUD, particularly regarding deep sedation not proportional to the extent of suffering or used in cases of purely existential distress, is under discussion, mostly because of the difficulty in objectively determining the refractory nature of the distress. Some French experts have argued that CDSUD might be somewhere between palliative care and euthanasia (Zittoun, Reference Zittoun2016). Consequently, continuous palliative sedation and CDSUD should be appropriately employed and not used as a substitute for intensively treating existential or non-physical distress at the end of life.

Despite the obvious need for knowledge on the topic, continuous palliative sedation and CDSUD are understudied as appropriate responses to refractory existential distress, and they are relatively underused in clinical practice. Recently, a French study of 8500 patients either followed in palliative care units or palliative care support teams, found that only 0.5% of them requested CDSUD, mostly for psycho-existential distress (69%) (Serey et al., Reference Serey, Tricou and Phan-Hoang2019). A Canadian survey of 322 palliative care physicians (response rate of 26%) found that 31% reported providing continuous palliative sedation in cases of existential distress alone. On a five-point Likert-type scale, 40% of the respondents disagreed and 43% of them agreed that continuous palliative sedation might be used for existential distress alone (Voeuk et al., Reference Voeuk, Nekolaichuk and Fainsinger2017). French Swiss physicians' attitudes toward palliative sedation were more favorable toward cases of physical than toward those with existential distress (Beauverd et al., Reference Beauverd, Bernard and Currat2014). Another French survey, conducted at two palliative care facilities in Marseille, found that 83% of the patients receiving palliative care supported the right to choose CDSUD, particularly in the presence of refractory pain, and 75% of them reported that it should be applied to suffering patients unable to express their wishes. More than two-thirds of the patient respondents (68%) reported that it should be available when a patient stops vital treatment (Boulanger et al., Reference Boulanger, Chabal and Fichaux2017).

Before proceeding with CDSUD, clinicians should analyze all the alleged reasons for the distress that generated the request. Physicians should use their clinical expertise and consider the unbearable nature of the distress from the patient's perspective. Physicians also should carefully investigate the patient's motives for the request and any ambivalence in the patient's expectations that might influence the medical decision to proceed or not (Vitale et al., Reference Vitale, de Nonneville and Fichaux2019). Doctors should interpret requests to hasten death in the patient's dynamic context because these requests tend to fluctuate, change, and evolve. Clinicians need to use sufficient time to consider and observe the patient's potentially evolving thought process while implementing adapted therapeutic measures. Patients' requests need to be understood in the context of their meaningful experiences and connections to others before clinicians act upon them (www.sfap.org, 2014).

Assessing psycho-existential distress is a multidisciplinary process using multidimensional criteria, which includes the palliative care team, psycho-oncological team, algologist team, and, if deemed necessary, a social work team and chaplaincy service. All of these professionals evaluate the situation from the perspectives of their respective fields as objectively as possible regarding the physical, psychological, social, and existential symptoms that seem to be contributing to the patient's situation. Evaluations should be periodically repeated along with assessments of the efficacy of applied and proposed treatment regimens. Patients' desires should be considered, and a mutual approach to the problems should be taken as much as possible to engage all parties.

The response to psycho-existential distress should not be limited to the implementation of CDSUD, even when patients request it. A therapeutic approach involving relational and emotional support, respect for rights, dignity, and autonomy (that cannot be limited to a request for CDSUD) is a possible alternative (Galushko et al., Reference Galushko, Frerich and Perrar2016). Treatment of the psychiatric conditions common to end-stage palliative patients (e.g., depression, anxiety, or delirium) must be attempted before implementing CDSUD because their effectiveness is well established (Johnson, Reference Johnson2018). It is important to recognize that CDSUD in response to refractory existential distress in cases of terminal illness might cause ethical dilemmas for clinicians and moral challenges for caregivers that might interfere with the smooth functioning of the caregiving teams (Plançon and Louarn, Reference Plançon and Louarn2018).

In cases of psycho-existential distress, CDSUD proposals might shatter patients', family members', and caregivers' psychic defenses because they might be overwhelmed by thoughts of death, which might make it impossible to implement measures intended to shorten life (Plançon and Louarn, Reference Plançon and Louarn2018). Therefore, caregivers of end-of-life patients experiencing existential distress should deeply reflect and observe; investigate death anxiety; try to identify risk factors for negative influences on existential distress; and try to enhance their patients' sense of meaning, continued personal growth, interventions, and self-care (Pessin et al., Reference Pessin, Fenn and Hendriksen2015). Because of the inconclusiveness and uncertainty about the ethical and clinical justifications of CDSUD in cases of psycho-existential distress, better understandings of the controversy and decision-making processes are needed. The goal would be to avoid using palliative sedation as a substitute for intensive treatment of refractory mental distress and to create specialized teams focused on palliative sedation (Bruce and Boston, Reference Bruce and Boston2011).

Physicians should consider several pharmacological and psychological interventions before implementing CDSUD for refractory psycho-existential distress. Clinicians should investigate the distress and determine its onset, whether it began before the patient became terminally ill, and the probability of it worsening during the disease's trajectory (Anquinet et al., Reference Anquinet, Rietjens and van der Heide2014). Clinician should consider the possibility that refractory physical symptoms with significant discomfort might be causing the psycho-existential distress (Plançon and Louarn, Reference Plançon and Louarn2018) Confronted with a CDSUD request, clinicians always should evaluate the patient's emotional and cognitive states and psychosocial dynamics. Then, all relevant therapeutic measures to treat the physical and mental symptoms should be employed, and efforts should be made to restore to the patient the sense of dignity and meaning that existed before she or he became terminally ill.

Conclusion

Diagnosing psycho-existential refractory symptoms is a mutual process between patients and their medical teams. The psycho-existential distress experienced by end-of-life patients should be considered from a global and multidimensional perspective in which the physical, psychological, and existential aspects are deeply entwined. Patients' subjective perceptions of their situations will likely interfere; however, evaluations of refractory distress by multidisciplinary expert teams in palliative care and mental health (psychiatrists and/or psychologists) add objectivity to the decision-making process.

Although the Claeys-Leonetti law is a useful framework as a safeguard to avoid the misuse of CDSUD, determining the refractory nature of psycho-existential symptoms is ethically controversial, and it presents a complex and challenging task, as the European Association for Palliative Care has pointed out (Juth et al., Reference Juth, Lindblad and Lynöe2010). CDSUD is a legal therapeutic possibility for responding to refractory psycho-existential distress, but rapid implementation eliminates relational and/or psychotherapeutic approaches to these patients' distress. Our literature review shows that regardless of the country, palliative sedation and mainly CDSUD request to treat psycho-existential distress depends on challenging situations with specific cultural and ethical issues. Sedation in the management of refractory psychological symptoms and existential distress is still a controversial issue and much debated. Recent literature shows that a shortage of evidence-based resources limits the current literature's ability to inform specific policy with consequences in daily clinical practice (Ciancio et al., Reference Ciancio, Miraz and Ciancio2019).

Since 2016, in France, mainly case reports are available about CDSUD practices and health care professionals' feelings (De Nonneville et al., Reference De Nonneville, Marin and Chabal2016; Boulanger et al., Reference Boulanger, Chabal and Fichaux2017; Plançon et al., Reference Plançon and Louarn2018; Vitale et al., Reference Vitale, de Nonneville and Fichaux2019). Larger studies, including multicentric surveys (Serey et al., Reference Serey, Tricou and Phan-Hoang2019) should be developed in the future to better understand indications and consequences on clinical practices.

Clinicians should consider the complexity of the contexts in which these requests are made and patients' ambivalence regarding results. Listening, learning, and analyzing the distress and its possible causes are effective and cautious medical practices regarding CDSUD, particularly in the context of multidisciplinary deliberative processes. In daily clinical practice, psychological and/or psychiatric monitoring and appropriate interventions should clearly distinguish between psycho-existential symptoms that are treatable and those that will remain refractory. CDSUD should not be “an option of first resort” (McCammon et al., Reference McCammon and Piemonte2015) but should remain an “exceptional last resort measure rarely necessary” (Twycross, Reference Twycross2019), whose implementation should be significantly reduced by effective palliative care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor N. Penel and our medical writer for their relevant advices.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.