INTRODUCTION

Demoralization is a common psychiatric disorder associated with the end of life. Hopelessness, helplessness, and the loss of purpose and meaning in life—the loss of morale—are key and central symptoms of demoralization syndrome (DS).

Research on DS indicates that it is associated with physical problems and such social and psychological variables as depression, anxiety, and pain, as well as reduced quality of life and a desire for hastened death (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2015). The diagnostic criteria for DS as proposed by Kissane (Reference Kissane2000) include: (1) an experience of emotional distress such as hopelessness and having lost meaning and purpose in life; (2) attitudes of helplessness, failure, and pessimism, and a loss of faith in a worthwhile future; (3) reduced ability to cope and respond flexibly; (4) social isolation and deficiencies in social support; (5) persistence of the abovementioned phenomena over two or more weeks; and (6) features of major depression not superseded as the primary disorder.

In a systematic review of DS in patients with advanced disease, Robinson and colleagues (2015) found that patients who are single, isolated, or jobless, have poorly controlled physical symptoms, or have inadequately treated anxiety and depressive disorders are at increased risk for DS. However, this review was limited in terms of a lack of variability of study characteristics.

Although there is a tendency among physicians to avoid patients' psychological suffering due to many constraints, there are several factors related to psychological suffering, and DS might be remediable with efficacious interventions (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Wilson and Enns1995). As such, further studies about DS are warranted in order to gain a better understanding of this aspect of end-of-life care. To date, the relationship between demoralization syndrome and other aspects of the end-of-life experience have not been evaluated in Portugal.

Our study aimed to assess the prevalence of DS and its clinical correlates with demographic, physical, psychiatric, and psychosocial factors within a sample of 80 terminally ill Portuguese patients.

PATIENTS, MATERIAL, AND METHODS

Patients

Patients were recruited from the Palliative Medicine Unit at the Hospital São Bento Menni in Lisbon, which delivers palliative care to terminally ill patients. Recruitment took place between May of 2010 and September of 2012. Patients were judged eligible for participation if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: age greater than 18 years; having a life-threatening disease with a prognosis of 6 months or less; no evidence of dementia or delirium based on documentation within the medical chart or by clinical consensus; a Mini-Mental State score equal to or greater than 20; being able to read and speak Portuguese; and provision of written informed consent.

The study was approved by the ethics committee at the Instituto das Irmãs Hospitaleiras do Sagrado Coração de Jesus, Casa de Saúde da Idanha, and by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Lisbon.

Design

This cross-sectional study was part of an overall randomized controlled trial (registered at http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN34354086) designed to evaluate the prevalence and associated demographic, physical, psychiatric, and psychosocial factors for demoralization syndrome in patients with advanced disease.

Evaluation

Patients who consented to participate were evaluated and administered several scales during a single session. These measures included: the so-called Demoralization Criteria (Kissane, Reference Kissane2000); the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM–IV (APA, 2000; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams2002); the Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) (Pais-Ribeiro et al., Reference Pais-Ribeiro, Silva and Ferreira2007); the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) (Bruera et al., Reference Bruera, Kuehn and Miller1991) (to reduce any redundancies in the protocol, items related to depression, anxiety, and well-being were removed from the ESAS, so that only physical symptoms were measured); and the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS). Demographic and illness-related information was collected directly from patients or their medical charts.

Patients with HADS subscale scores of 11 or greater were considered to have exceeded the clinically significant critical threshold criteria for depression and anxiety (Pais-Ribeiro et al., Reference Pais-Ribeiro, Silva and Ferreira2007).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed in order to characterize the study sample. The association between independent factors and prevalence of demoralization syndrome was examined using Pearson's chi-square test, with prevalence ratios calculated for categorical variables. A multivariate analysis was then performed to evaluate the independent associations between the significant univariate factors and prevalence of DS. For this step, we included only the variables with a significant association with DS (p < 0.05) using the Poisson regression model. All analyses were done using STATA SE 11.1 software.

RESULTS

A total of 165 patients were admitted to the palliative care unit at the Hospital São Bento Menni during the period of analysis. Some 85 subjects did not fulfill the inclusion criteria (60 were fatigued or physically uncomfortable; 12 had delirium, and 8 had a Mini-Mental State score below 20). A final sample of 80 terminally ill individuals was included. The summary demographic and illness data are presented in Table 1.

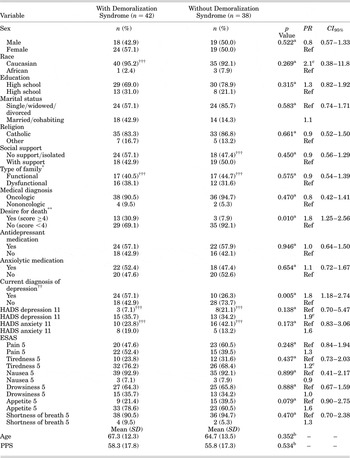

Table 1. Summary characteristics of participants (N = 80)

* Lung, n = 16; ovarian, n = 7; glioblastoma, n = 6; uterus, n = 5; cecum, n = 4; breast, n = 4; bladder, n = 3; stomach, n = 3; larynx, n = 3; tongue, n = 3; prostate, n = 3; esophagus, n = 2; chronic myeloid leukemia, n = 2; melanoma, n = 2; neoplasm of the nose, n = 1; unknown primary cancer, n = 2; colon, n = 1; endometrium, n = 1; glioma, n = 1; small bowel neuroendocrine tumor, n = 1; multiple myeloma, n = 1; dorsal neurinoma, n = 1; pancreas, n = 1; vascular arterial cancer, n = 1.

† Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, n = 3; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n = 2; trigeminal neuralgia, n = 1.

†† 1 record missing.

** Palliative Performance Scale: 100% = healthy, 0% = death.

Prevalence of Demoralization Syndrome

The prevalence of DS was 52.5%.

Demoralization Syndrome and Demographic Factors

No statistical differences were observed between patients with and without DS in respect to sex, age, race, education, religion, type of family, medical diagnosis, medication, marital status, and social support.

Demoralization Syndrome and Physical Factors

The average ESAS score on each physical item was as follows: pain (4.25, SD = 2.94); tiredness (5.58, SD = 2.52); nausea (0.84, SD = 2.00); drowsiness (4.49, SD = 2.56); appetite (4.56, SD = 2.59); well-being (3.39, SD = 2.74); and dyspnea (0.83” SD = 2.16). There was no relationship between ESAS scores and DS. Performance status also did not show statistical differences between patients with and without DS.

Psychological Factors: Depression and Anxiety

Based on the DSM–IV, 42.5% of the study sample met the criteria for a major depressive episode, and 30% met the criteria for both DS and depression. The average sample scores on the HADS depression and anxiety subscales were 13 (SD = 4.33) and 9 (SD = 4.55), respectively.

Patients with or without DS did not differ in respect to anxiety and depressive symptoms according to the HADS. A diagnosis of clinical depression using DSM–IV criteria was significantly associated with DS (PR = 1.8, CI 95% = [1.18–2.74]) (Table 2). Likewise, a significant association between DS and desire for death (PR = 1.8, CI 95% = [1.25–2.56]) was also observed (Table 2).

Table 2. Demographic, psychiatric, and psychosocial characteristics of the 80 terminally ill patients with or without demoralization syndrome

CI = confidence interval; ESAS = Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PPS = Palliative Performance Scale; PR = prevalence ratio; Ref = reference variable.

* Kissane & Bloch (Reference Kissane and Bloch2002).

** Chochinov et al. (Reference Chochinov, Wilson and Enns1995).

†† DSM–IV.

††† Records missing.

* Pearson's chi-square.

b Mann–Whitney test.

Independent Factors Associated with Demoralization Syndrome

We utilized Poisson regression analyses to identify the independent factors significantly associated with DS, after which neither a diagnosis of depression using the DSM–IV nor the desire for death emerged as significant factors (DSM–IV criteria: PR = 1.6, CI 95% = [0.84–3.08]; desire for death: PR = 1.5, CI 95% = [0.74–2.99]).

DISCUSSION

The aim of our study was to investigate the prevalence of DS in a sample of terminally ill Portuguese patients and its associated factors. While this issue has been studied before and in other countries, it has not as yet been examined in a Portuguese population.

There are some noteworthy observations to be drawn from our study. First, 42.5% of our patient sample met the diagnostic criteria for clinical depression, and almost half the participants scored more than 11 on the HADS depression subscale. This high prevalence of depression appears to be higher than what has previously been reported in the literature (Hotopf et al., Reference Hotopf, Chidgey and Addington-Hall2002), indicating a high level of psychological distress within this sample of terminally ill Portuguese patients, as reported elsewhere (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013a ; Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013b ; Reference Julião, Oliveira and Nunes2014; Reference Julião, Nunes and Sobral2015). This may reflect a lack of psychosocial support services or a paucity of effective interventions being offered to these patients over the course of their illness (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013a ,Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira b ). Depressed patients, based on DSM–IV criteria, were nearly twice as likely to have DS when compared with nondepressed patients. These results confirm various studies that have shown this particular clinical association (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004; Vehling et al., Reference Vehling, Lehmann and Oechsle2012; Mullane et al., Reference Mullane, Dooley and Tiernan2009; Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Rossi and Sabato2004), indicating a high degree of influence between these two psychiatric conditions (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2015). Some 30% of our study participants had an overlap between a diagnosis of DS and clinical depression. There is growing body of evidence showing that a substantial percentage of terminally ill patients can present with DS yet not be classified as being depressed. At this point, our study failed to show whether DS and depression are two distinct psychological entities. This fact calls for future research supporting the clinical importance of DS and the need to consider it as a separate psychosocial diagnosis in end-of-life care (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2015).

Our study demonstrated a very high prevalence of DS compared with the 13–18% reported in the systematic review conducted by Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Kissane and Brooker2015), which employed the same categorical measures that we applied. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest prevalence of DS published to date. This finding might be due to the fact that our patient sample had a high level of psychosocial distress, as indicated by the high prevalence of depression (based on the DSM–IV and HADS depression subscale scores). Perhaps unrecognized and poorly treated clinical depression increases anhedonic states, lowering morale, eliciting helplessness and hopelessness, culminating in demoralization and more severe suffering toward the end of life.

Our findings also confirm other previously published studies showing that DS appears to be related with a desire for death (DFD) (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Vanderwerker and Block2006; Mullane et al., Reference Mullane, Dooley and Tiernan2009). Patients presenting clinically significant DFD were 1.8 times more likely to have DS when compared to participants without DFD. It has been shown that hopelessness and meaninglessness—key features of DS—can be independent and strong predictors of suicidality (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman1975; Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Wilson and Enns1998; Breitbart et al., Reference Breitbart, Rosenfeld and Pessin2000). A previously published study on DFD in terminally ill Portuguese patients showed that depression is a strong predictor of a desire to die sooner (Julião et al., Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira2013a ,Reference Julião, Barbosa and Oliveira b ). Perhaps the very high prevalence of clinical depression at baseline reflected a lack of psychiatric support for Portuguese patients facing life-threatening diseases. Inadequately treated depression is a well-established correlate of a desire to die.

Although our results add some important evidence to enhance our understanding of DS toward the end of life in a sample of Portuguese patients, there are some notable limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small and composed primarily of older, end-stage cancer patients. Therefore, future research with younger patients and/or advanced noncancer terminal conditions is warranted. Our results might not be representative of terminally ill Portuguese patients who either avoid or do not have access to palliative medicine.

Finally, we employed a cross-sectional study design. While our study represents an important snapshot of patient experience, it does not offer any insight into how DS may evolve over time.

The results of our study provide important insights into DS and how it presents in palliative care clinical practice in a sample of terminally ill Portuguese patients. While our findings reinforce many previous studies on DS and its various associations and variables, it also provides some new and interesting findings regarding the context within which DS unfolds. A better understanding of DS and its related factors might help healthcare providers respond more effectively to patients as they approach the end of life.

CONTRIBUTORS

MJ and AB were responsible for the conception and design of the study. MJ was responsible for supervising the study, analyzing the data, and writing the initial draft and final report. BN supervised the statistical data analysis. All of the coauthors helped in revising the final draft and had full access to all the data.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors hereby state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to express special thanks to Professor Harvey Max Chochinov.