Introduction

Preferences for end-of-life (EoL) care settings (i.e., home, hospital, or inpatient hospice unit) are one of the most influential factors for determining the actual place of death (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Calanzani and Koffman2015). Previous studies have shown that culture shapes preferences regarding decision making associated with EoL care (e.g., Cain et al., Reference Cain, Surbone and Elk2018; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Yates and Thorberg2019). Bentur et al. (Reference Bentur, Emanuel and Cherney2012) stated that “for many Jews in Israel the concept of ‘sanctity of life’ (kedushat hakhayim) is a central value; this contributes to a tendency for patients to request and for physicians to provide ‘aggressive’ modes of care even as patients approach the end of life” (p. 3). Thus, we sought to explore preferences for EoL care settings among the healthy population in Israel.

In a systematic review conducted by Gomes et al. (Reference Gomes, Calanzani and Gysels2013), 24 studies showed that the majority of the general public (52–92%) preferred dying at home. The preference for this setting stems from the notion that the home, where the patient is generally surrounded by family, seems to enable greater peace for patients at the EoL (Calanzani et al., Reference Calanzani, Higginson and Gomes2013; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Calanzani and Koffman2015). However, several researchers noted that the preference for dying at home, from the relatives’ perspectives, is inconsistent, considering pain control and levels of grief (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Keating and Balboni2010; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Calanzani and Koffman2015), suggesting that decisions regarding EoL care settings are not easy choices.

Hospices or palliative care units were the second most frequently chosen settings for EoL care (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Higginson and Calanzani2012). According to the World Health Organization (2002), palliative care is designed to improve the quality of life of patients with a serious illness and their families. Indeed, several researchers showed that hospice care units improve quality of care and satisfaction among patients and caregivers (e.g., Seaman et al., Reference Seaman, Bear and Documet2016). Nevertheless, other studies noted that the term “palliative care” or “hospice” carries a stigma for physicians, patients, and their caregivers, who regard it as synonymous with death and dying, diminished possibilities of hope for cure, loss of control, hopelessness, and abandonment (Collins et al., Reference Collins, McLachlan and Philip2017; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Chen and Lin2017). Likewise, Shen and Wellman (Reference Shen and Wellman2019) found that palliative care stigma was associated with less prospective usage of palliative care for one's self and for one's family members as it was associated with negative stereotypes such as quitters, lazy, hopeless, and weak-willed. These inconsistent findings highlight the complexity regarding EoL care decisions.

The setting least chosen for EoL care noted by Gomes et al.'s (Reference Gomes, Higginson and Calanzani2012) research was hospitals. Some researchers and clinicians who explored cancer patients, caregivers, and clinicians found that unexpected health changes such as family caregivers becoming overwhelmed with the responsibility of caring and controlling severe symptoms, caused respondents to feel unsafe at home and to favor institutional care (Rainsford et al., Reference Rainsford, Phillips and Glasgow2018). However, hospital wards are often characterized with multi-occupancy rooms and noise that negatively impact on patient's experiences at EoL (Brereton et al., Reference Brereton, Gardiner and Gott2012). Moreover, Donnelly et al. (Reference Donnelly, Prizeman and Coimín2018) revealed in a quantitative descriptive post-bereavement postal survey that bereaved relatives felt that patients’ psychological, emotional, and spiritual care needs were not always fully considered and responded to appropriately or in a timely manner.

Possible associations with EoL care settings were proposed in relation to socio-demographic variables; Gomes et al. (Reference Gomes, Higginson and Calanzani2012) found in a cross-national comparison among the general public in Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain that the preference for home death decreased with age up to 60 years old and increased in the age groups 60–69 and 70+. In addition, previous experiences of caring for a close relative or friend with cancer had no influence on the preference for home care. In a systematic review of the United Kingdom literature, Calanzani et al. (Reference Calanzani, Higginson and Gomes2013) found that choosing hospice or a palliative care unit as the preferred place of death was reported by those with younger age, and among those who had cared for or experienced the death of a relative or friend. With regard to gender differences, Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Prigerson and Penedo2015) found among men with metastatic cancers that they were three times more likely than women to receive EoL care in an intensive care unit. Likewise, in a German survey concerning preferences of place of death in a theoretical scenario, women stated that they preferred not to die in a hospital (Fegg et al., Reference Fegg, Lehner and Simon2015). Concerning marital status, preference for dying at home was more common than preference for dying in a hospice or hospital among people who had never married or were never in a relationship (Foreman et al., Reference Foreman, Hunt and Luke2006). Individuals with poor self-rated health were found to be less likely to prefer being cared for at home (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Wong and Kiang2017). Regarding education level, results revealed inconsistency; Hamano et al. (Reference Hamano, Hanari and Tamiya2020) did not find a correlation between the level of education and preferences for EoL care among the general public, while Chung et al. (Reference Chung, Wong and Kiang2017) found that post-secondary education or above was associated with an increased preference to be cared for and to die at home (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Wong and Kiang2017). Likewise, the results involving religiosity revealed inconsistency; Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Cohen and Deliens2013) found no correlation between religion and preference for a specific EoL care setting. However, Pradilla et al. (Reference Pradilla, Ospina and Alonso-Babarro2011) revealed that among those who practiced a religion, 74.6% preferred EoL home care, 22.4% preferred a hospital palliative care unit, and 3.0% an acute care hospital.

Given the above, the current study sought to explore preferences for EoL care settings, namely home, hospital, or inpatient hospice units, among the general healthy population in Israel and possible associations with socio-demographic variables. The current hypotheses were examined: (1) Most of the participants would prefer EoL home care rather than hospital or hospice units; (2) Older age, single family status, male gender, lower self-rated health, lower level of education, and previous exposure to cancer of close relatives or friends would indicate preference for EoL institutional care such hospitals or hospice units. In addition, religiously oriented individuals would prefer EoL hospital care.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study used an internet panel of about 130,000 Israelis that adheres to the Israel Bureau of Statistics in key demographic factors, including age, gender, and marital status, that represent the general population (Bodas et al., Reference Bodas, Siman-Tov and Kreitler2017). From this panel, potential participants were invited to participate in the study via e-mail. Eligibility to participate in the study included age 18 or older, no history of cancer illness, and fluency in Hebrew. The study was approved by the authors’ affiliated University IRB committee.

A sample of 311 Israelis was selected using stratified and random sampling methods based on age, gender, and marital status, in order to obtain a sample that is a close approximation to the general population. Each participant signed an electronic informed consent form before accessing the questionnaire. The mean age of the sample was 40.2 years (SD = 14.8; range 18–70). The sex ratio was almost 1:1 with 158 women (50.8%) and 153 men (49.2%). The majority of the sample was in a committed relationship (n = 212; 68.2%). Education was divided into four categories: elementary school 2 (0.6%), partial high school 12 (3.9%), graduated high school 138 (44.4%), and academic 159 (51.1%). Self-rated health was distributed as follows: poor 3 (1.0%), mediocre 29 (9.3%), good 160 (51.4%), and excellent 119 (38.3%). Regarding religiosity, 156 were secular (50.2%), 102 traditional (32.8%), 34 religious (10.9%), and 19 ultra-orthodox (6.1%). All participants were Jewish and born in Israel. Previous exposure to cancer was noted by 54.0% (n = 168) of the participants.

Instruments

The following battery of self-report questionnaires was administered: Socio-demographic — relating to age, gender, marital status, religiosity, education, and self-rated health that was assessed on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = bad to 4 = excellent) (Benyamini et al., Reference Benyamini, Blumstein and Lusky2003). In addition, previous exposure to cancer of close relatives or friends was reported (1 = being exposed to cancer; 2 = not being exposed to cancer).

Preferences of EoL care setting were measured using three separate items taken from the Attitudes of Older People to End-of-Life Issues Questionnaire (AEOLI; Catt et al., Reference Catt, Blanchard and Addington-Hall2005). First: “If I were severely ill with no hope of recovery, I would rather be cared for in an inpatients hospice unit than at home.” Second: “If I were severely ill with no hope of recovery, I would rather be cared for in a hospital than in an inpatients hospice unit.” Third: “If I were severely ill with no hope of recovery, I would rather be cared for in a hospital than at home.” Each question was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “1” strongly disagree to “5” strongly agree. Higher values meaning more agreement with the designated preference.

Statistical analysis

In order to test the first hypothesis, we present an extensive description of the dependent variables. For the second hypothesis, we conducted a simple correlation matrix in order to learn about associations between the study variables and the dependent variables. Finally, we conducted regression analyses in order to learn of the associations separately for preferences of each of the three-care settings (namely home, hospice unit, and hospital) with socio-demographic variables and previous exposure to cancer.

A preliminary analysis was conducted for potential Multicollinearity. Applying the rules used in the literature stating that tolerance of less than 0.20 and/or variance inflation factor (VIF) of 5 and above indicate a multicollinearity problem (O'Brien, Reference O'brien2007). The preliminary analysis of the hierarchical regressions yielded tolerance ranging from 0.629 to 0.966 and VIF of 1.036−1.589. These results indicated that there was no multicollinearity problem. The regression was re-estimated using 5,000 bootstrapped draws.

Results

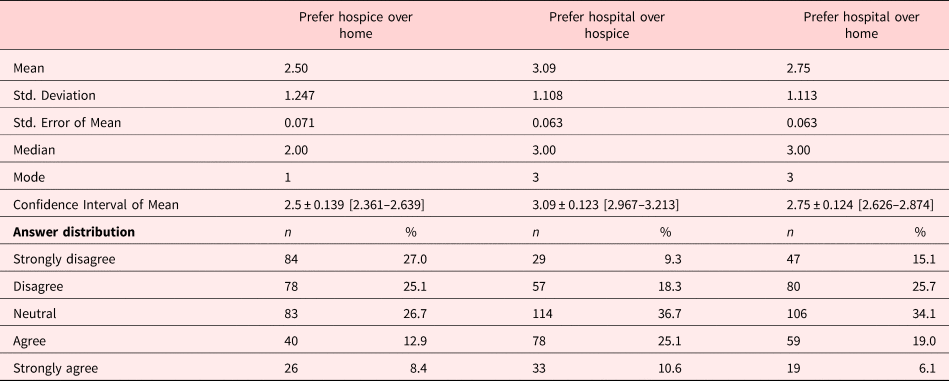

The distribution of preferences of EoL care settings can be seen in Table 1. Regarding the question: “If I were severely ill with no hope of recovery, I would rather be cared for in an inpatient hospice unit than at home,” 52.1% of the participants stated “disagree” and “strongly disagree” to be cared for in inpatient hospice unit rather than at home. In referring to the question, “If I were severely ill with no hope of recovery, I would rather be cared for in a hospital than in an inpatient hospice unit,” 35.7% of the participants stated “disagree” and “strongly agree” to be cared for in hospital rather than in an inpatient hospice unit.” Finally, concerning the question, “If I were severely ill with no hope of recovery, I would rather be cared for in a hospital than at home,” 40.8% stated “disagree” and “strongly disagree” to be cared for in a hospital rather than at home.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables regarding preference for end-of-life care (n = 311)

Regarding gender differences, men scored higher on the preference “Cared for in an inpatient hospice unit rather than at home” in comparison to women (men = 2.65 [SD = 1.30] vs. women = 2.36 [SD = 1.17]; t = 2.082; p = 0.038). The same was true for the other two preferences: “Cared for in a hospital rather than an inpatient hospice unit” (men = 3.32 [SD = 1.12] vs. women = 2.87 [SD = 1.06]; t = 3.626; p < 0.001) and “Cared for in hospital rather than at home” (men = 2.95 [SD = 1.17] vs. women = 2.56 [SD = 1.02]; t = 3.087; p = 0.002).

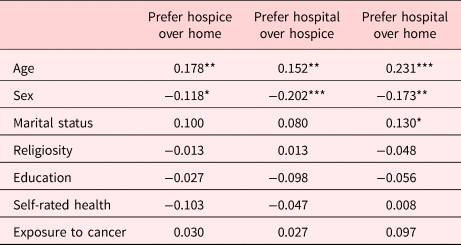

Examining the second study hypotheses, Pearson correlations were calculated between socio-demographic variables and previous exposure to cancer (the independent variables) with preference for EoL care setting which was the dependent variable (see Table 2). As can be seen, among the socio-demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, marital status, religiosity, education, and self-rated health) and previous exposure to cancer, only age and gender were found to be associated with EoL setting preferences. Specifically, both older age and male gender were significantly, but weakly associated with preferences for EoL hospice or hospital care rather than EoL home care, and EoL hospital rather than EoL hospice care.

Table 2. Correlations between demographic variables and exposure to cancer with variables regarding preference for end-of-life care (n = 311)

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

In addition, the results of the regressions analyses regarding the dependent variable — EoL care settings (see Table 3) revealed that no demographic variable or exposure to previous cancer (the independent variables) were found to be associated with preference to be cared for in an inpatient hospice unit rather than at home. However, male gender was associated with preferences for be cared for in hospital rather than in an inpatient hospice unit (B = −0.381; Std. β = 0.106; t = −2.985; p < 0.01). Moreover, older age (B = 0.015; Std. β = 0.203; t = 2.927; p < 0.01) and male gender (B = −0.253; Std. β = −0.114; t = −1.991; p < 0.05) were positively associated with preference for cared for in a hospital rather than at home.

Table 3. Regressions analyses of the association between each of the attitudes toward end-of-life care and demographics variables (n = 311)

Note: Gender was coded as (1 = Male; 2 = Female); Marital status was coded as (1 = not being in a committed relationship; 2 = being in a committed relationship); Religiosity was coded as (1 = secular; 2 = traditional; 3 = religious; 4 = ultra-orthodox); Education was coded as (1 = elementary school; 2 = partial high school; 3 = graduated high school; 4 = academic); Previous exposure to cancer was coded as (1 = being exposed to cancer; 2 = not being exposed to cancer).

2 p < 0.05.

3 p < 0.01.

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore preferences for EoL settings (i.e., home, hospice unit, and hospital) among the healthy population in Israel by focusing on socio-demographic variables. Our findings revealed a complex picture regarding preferences of EoL settings. Home was preferred by some individuals, while others preferred to be cared for in inpatient hospice units or hospitals. In addition, when participants were asked if they preferred to be cared for in hospital rather than in a hospice unit, 36.7% had no preference, followed by 35.7% who preferred EoL hospital care.

Previous studies found that home was the preferred setting for EoL care (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Higginson and Calanzani2012; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Cohen and Deliens2013). Similarly, some of our study participants declared that they also would prefer EoL home care. This may be explained through the terror management theory (TMT) perceptive, which is based on the assumption that to achieve psychological equanimity humans are continuously propelled to drive thoughts of death out of conscious awareness (e.g., Pyszczynski et al., Reference Pyszczynski, Greenberg and Solomon1999), suggesting that the home is the least likely setting to arouse mortality salience due to its characteristic peaceful atmosphere (Rainsford et al., Reference Rainsford, Phillips and Glasgow2018). In line with this notion, it seems that hospice units and hospital wards represent care settings that are identified with dying patients (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Higginson and Calanzani2012). In addition, the familiarity of the home allows people to be surrounded by their personal belongings and loved ones (Calanzani et al., Reference Calanzani, Higginson and Gomes2013), and thus might suppress death-related thoughts that can emerge in institutional care settings. Nevertheless, some of our participants revealed positive attitudes toward institutional locations by indicating no preferences regarding hospital vs. hospice (36.7%). These results might suggest caution in assuming home as the ultimate preferred location for EoL care. Moreover, 35.7% of the participants in our study preferred to be cared for in a hospital rather than in a hospice unit. This might be explained through Schultz et al. (Reference Schultz, Baddarni and Bar-Sela2012) reflections on palliative care in the Jewish tradition. The authors claim that in Judaism, “even if the goal is not a cure, one common approach is to do whatever is possible to extend life, since one moment of life in this world is more valuable than all the world to come” (p. 4). Moreover, according to Torah-mandated Jewish law (Halakha), life is a gift of God and as such, the individual is entrusted with maintaining health and seeking preventative and curative medical care as required (Gabbay et al., Reference Gabbay, McCarthy and Fins2017). Thus, it is possible that the participants perceived the hospital as the place where medical interventions are more acceptable and where their course of illness will be actively addressed in contrast to palliative units which focus on the provision of comfort and alleviation of pain and suffering (Sholjakova et al., Reference Sholjakova, Durnev and Kartalov2018).

Findings with socio-demographic variables that were explored in relation to the explained variance of preferences toward EoL care settings, indicate that older age was associated with positive attitudes toward being cared for in a hospice unit or hospital in comparison to home. A possible explanation can be that at the EoL, home care involves dependency on significant others or family members that need to address the patient's nursing needs, which might produce feelings of being a burden. Indeed, in Judaism, the duty of filial responsibility is expressed in the fifth commandment “Honor thy father and thy mother.” As the great majority of elderly people in Israel live in close proximity to at least one of their children, elderly people are commonly cared for by their children (Lavee and Katz, Reference Lavee and Katz2003). In line with this notion, research conducted among the general public in South Dakota (Hughes, Reference Hughes2015) revealed that older respondents (age 60–95) were more likely to say it was “very important” not to be a burden on family at the EoL. Moreover, Israel's four health plans operate home medical care units that provide palliative care for patients with metastatic cancer and neurological and degenerative diseases; however, the staff are typically available only during normal working hours while during the evening and at night they are not generally available to provide these services (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Waitzberg and Merkur2015), Hence, it might be that older people prefer to be cared for in a setting which is recognized as having 24/7 services, that might address their needs without any additional burden on significant others or family members. In line with this notion, Waller et al. (Reference Waller, Sanson-Fisher and Zdenkowski2018) revealed among oncology outpatients that the top five perceived benefits concerning hospital were in the descending order: “pain being managed well, not being a burden to family and friends, having medical staff on call, family being able to have a more ‘normal life,’ and having access to lots of medical care” (p. 38).

Regarding gender, our findings show that the explained variance of preference for hospital care in comparison with home care was mainly related to male gender. A possible explanation can be that men may feel safer in institutional settings, particularly if care at home may be perceived with less pain management and with greater burden on family members (e.g., Calanzani et al., Reference Calanzani, Higginson and Gomes2013). Indeed, previous studies showed that fear of becoming dependent on the family, perceiving oneself as a financial burden to others and lacking social support were related to acceptance of a hastened death (Rietjens et al., Reference Rietjens, van der Heide and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2006; Yun et al., Reference Yun, Kim and Sim2018). Moreover, Broom and Cavenagh (Reference Broom and Cavenagh2010) suggested through a qualitative research among home care patients that the sense of eroded masculine identity owing to home care increased the feeling of being a burden, the need to accept help from family members and lack of independence. Likewise, Ullrich et al. (Reference Ullrich, Grube and Hlawatsch2019) found that among male patients with incurable, progressive diseases, receiving home palliative care, and dependence on others correlated with a sense of diminished social value and a stronger need for maintaining one's masculine identity. Another explanation may be related to cultural aspects. According to Schultz et al. (Reference Schultz, Baddarni and Bar-Sela2012), in Judaism, some patients or their families might refuse home palliative care because they see it as a prohibited form of “giving up” on healing. Thus, in line with the masculine identity that also highlights the need to fight and not to give up (Ullrich et al., Reference Ullrich, Grube and Hlawatsch2019), preference for hospital-based care among men is understandable.

Implications

The current findings raise possible implications. First, exploring preferences for EoL care settings among healthy populations will allow health policy makers to develop suitable interventions regarding EoL decision making, palliative care knowledge and effective ways of communication regarding EoL care settings. This is highly recommended as in the present study participants rated neutral attitudes concerning EoL care in a hospice unit vs. a hospital, although each setting has a different purpose. Thus, public health campaigns may be recommended to “change the narrow understandings of palliative care, reframing underlying narratives from those of disempowered dying to messages of choice, accomplishment and possibility” (Collins et al., Reference Collins, McLachlan and Philip2017, p. 7). Moreover, this campaign should be tailored with sensitivity to age and gender as these background characteristics were found to have a role in preferences for EoL care settings. Second, caution is needed in assuming that home care should be the default location for future care of terminal patients. Thereby, clinicians should offer opportunities for discussion of EoL care settings throughout the trajectory of a life-threatening illness, and not only near death, in order to enable informed decision making by their patients regarding EoL care preferences. Given the key role of informal caregivers and the influence that perceived family burden may have on patient choices, it would be preferable to ensure that the patient's choice can be supported by their family members (Waller et al., Reference Waller, Sanson-Fisher and Zdenkowski2018). For example, they can apply a multidisciplinary family meeting approach that can convey information, discuss goals of care, and plan care strategies with patients and family caregivers regarding EoL care and decisions (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Quinn and O'Hanlon2008).

Limitations

Several important limitations need to be acknowledged. First, our data are cross-sectional in nature and do not allow for causal hypotheses. As such, longitudinal studies would be recommended to examine if and why preferences change over time, especially since the present study was conducted among a healthy and young population, and preferences may change with the advance of age and illness. Second, the study was limited to Israel and possibly influenced by its health system and the culture-specific characteristics of its citizens; thus, generalizability to EoL care preferences for individuals in other countries is limited.

Conclusions

The current research highlights the importance of exploring preferences of end-of-life care settings among healthy populations in a variety of countries in order to develop appropriate culturally sensitive EoL healthcare policies. Our findings reinforce the role of age and gender in reference to attitudes toward EoL care settings and highlight the variety of Eol setting preferences, suggesting caution in assuming home as the ultimate choice at the EoL.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for Non-Medical Human Research of the authors’ university. The participants were included after giving their informed consent.

Funding

The study was not supported by any external funding. There was no assistance in this research or writing of this article other than the authors.

Conflict of interest

All authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and that there was no financial support for this work that could influence its outcome.