INTRODUCTION

More than 1.5 million Americans are projected to be diagnosed with cancer in 2014 (Siegel et al., Reference Siegel, Ma and Zou2014). For many, pain will pose a significant challenge to daily life. Pain is one of the most common and feared consequences of a cancer diagnosis, and, despite the availability of effective therapies, undertreatment of cancer pain is common (van den Beuken-van Everdingen et al., Reference van den Beuken-van Everdingen, de Rijke and Kessels2007). In fact, up to half of cancer patients do not receive appropriate pain management (Deandrea et al., Reference Deandrea, Montanari and Moja2008; Fairchild, Reference Fairchild2010). Severe cancer pain is associated with diminished quality of life (Tavoli et al., Reference Tavoli, Montazeri and Roshan2008) and with avoidable utilization of ambulatory care and emergency department services (Wagner-Johnston et al., Reference Wagner-Johnston, Carson and Grossman2010), as well as delay or discontinuation of cancer therapy (McNeill et al., Reference McNeill, Sherwood and Starck2004).

Provision of cancer care is complex, frequently involving the participation of multiple specialists, the application of invasive treatments, and management of dynamic and disparate symptoms and side effects. Prior research has found provider communication and coordination of care to be associated with better pain management (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Richman and Hurley2002; Antón et al., Reference Antón, Montalar and Carulla2012; Yates et al., Reference Yates, Edwards and Nash2002), and a recent systematic review highlighted the need for enhanced patient-centered care to improve pain control in cancer (Luckett et al., Reference Luckett, Davidson and Green2013). While the concept of patient-centered care is not new, progress in integrating the patient into emergent models of cancer care has been inconsistent at best. A recent report by the Institute of Medicine underscored the continuing need to improve communication, coordination, and patient-centeredness in cancer care (National Research Council, 2013).

Patient-reported measures of quality are increasingly being employed to evaluate medical care, including the quality of oncology practice (Ayanian et al., Reference Ayanian, Zaslavsky and Guadagnoli2005; Reference Ayanian, Zaslavsky and Arora2010; Dennison, Reference Dennison2002). Because of the individualized nature of cancer pain and pain management, patient-reported measures of the quality of interpersonal aspects of care, such as physician communication, may be uniquely associated with patient pain in cancer. The majority of prior research on patient-reported quality of care in pain has focused on the specific association among patient satisfaction, pain management, and pain severity (McCracken et al., Reference McCracken, Klock and Mingay1997; Miaskowski et al., Reference Miaskowski, Nichols and Brody1994; Panteli & Patistea, Reference Panteli and Patistea2007; Ward & Gordon, Reference Ward and Gordon1994). Moreover, the small body of literature linking patient-reported quality of cancer care to symptom burden has looked at satisfaction as a global metric rather than patients' assessments of specific aspects of care (Avery et al., Reference Avery, Metcalfe and Nicklin2006; von Gruenigen et al., Reference von Gruenigen, Hutchins and Reidy2006).

To date, patient-reported quality of interpersonal care has not been studied in relation to the cancer pain experience. Consequently, we have a limited understanding of the aspects of interpersonal care that may be appropriate targets for quality improvement efforts aimed at reducing the burden of cancer pain. The purpose of our study was to examine the association between patient assessment of three aspects of interpersonal care—physician communication, coordination/responsiveness of care, and nursing care—and pain severity in a large, nationally representative cohort of colorectal and lung cancer patients (Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Ayanian and Weeks2013).

METHODS

Study Population and Survey Methods

Participants in the study came from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) prospective cohort study of newly diagnosed colorectal and lung cancer patients, which included nearly 10,000 participants at seven geographically diverse data collection sites throughout the United States.

Participants were recruited between three and five months following diagnosis. Following consent, patients were administered a survey via computer-assisted telephone interview in English, Chinese (Mandarin), or Spanish. Data were collected between 2003 and 2005. Additional details about the CanCORS cohort and study design were reported by Malin and colleagues (Reference Malin, Ko and Ayanian2006).

Our analytic cohort included all individuals who completed the survey and reported any pain. Presence of pain was established through responses to two questions: “Have you experienced pain in the past four weeks?” and “Have you been taking medication for pain in the past four weeks?” Individuals responding “yes” to either or both questions were considered to have pain.

Independent Measures

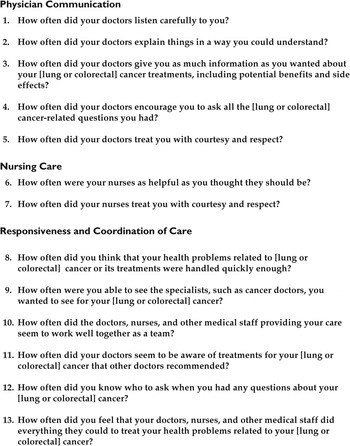

A 13-item instrument developed by the CanCORS study team assessed participants' assessment of specific aspects of cancer care (Malin et al., Reference Malin, Ko and Ayanian2006). Prior psychometric testing on this instrument established the presence of three distinct factors: coordination/responsiveness of care (six items), nursing care (two items), and physician communication (five items) (Ayanian et al., Reference Ayanian, Zaslavsky and Arora2010). Consistent with prior use of the instrument, we transformed scores for each of the factors into 100-point scales, with 100 being the best possible rating of care and 0 the worst. Items and their corresponding factors are presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Assessment-of-care items and interpersonal care domains.

Scores for the three interpersonal care domains were previously treated as continuous measures (Ayanian et al., Reference Ayanian, Zaslavsky and Arora2010). However, because we were specifically interested in the difference between patients reporting no problems with care and those reporting any problems with care, we dichotomized patient ratings into each domain as optimal (100) versus nonoptimal (≤99).

Dependent Measure

The dependent measure in this study was self-reported pain severity, assessed through survey-based administration of the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Cleeland & Ryan, Reference Cleeland and Ryan1994). The BPI asks respondents to rate their pain during the past 4 weeks (worst, least, and average) on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being the least imaginable pain and 10 the most. We created an aggregate pain severity score for each patient based on the mean of their worst, least, and average pain scores. We then transformed these scores into 100-point scales, with 0 being the least pain and 100 the most. We defined a minimal clinically important difference for pain severity in our analysis as a difference of ≥10 on the 100-point scale (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Sloan and Wyrwich2003; Salaffi et al., Reference Salaffi, Stancati and Silvestri2004). We analyzed pain severity as a continuous measure.

Covariates

Based on an extensive review of the literature, we included a number of control measures. Sociodemographic covariates included race/ethnicity, age, sex, marital status, educational level, and wealth. We categorized race/ethnicity as white, black, Hispanic/Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander (API), multiple races, and other (including Native American) according to participant self-report.

We categorized age as 18–54, 55–64, 65–74, and 75 years or older. We subdivided participant sex as male or female, and marital status as “married/living with a partner,” “widowed/divorced/separated,” or “never married.” We categorized education as “less than a high school diploma,” “high school diploma but less than four-year college graduate,” or “four-year college graduate or higher.”

Participant wealth was measured through responses to the question “If you lost all of your current sources of income (for example, your paycheck, Social Security or pension, public assistance) and had to live off your savings, how long could you continue to live at your current address and standard of living?” We categorized this length of time as “less than one month,” “one month to a year,” and “more than one year.”

Survey language (English, Spanish, or Mandarin) was coded by the survey administrator, and we utilized this variable as a covariate to account for acculturation.

Health status variables in our analysis included cancer stage and presence of depressed affect. Stage was determined through evaluation of the medical record and other staging information by the CanCORS Statistical Coordinating Center. We dichotomized this as stage 4 versus stages 1–3.

Depressed affect has been shown to be associated with worse pain experience in cancer (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Wu and Bair2011). This was measured through an eight-item adaptation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Short Form (CESD–SF), which we dichotomized as “yes” or “no” based on a cutpoint of ≥6 to indicate presence of depressed affect (Turvey et al., Reference Turvey, Wallace and Herzog1999).

Statistical Analysis

We employed descriptive statistics to compare the characteristics of patients reporting nonoptimal care (≤99) versus optimal care (100) in the three interpersonal care domains. To explore the unadjusted associations between patient-reported quality of care and pain severity, we examined mean BPI scores associated with patient report of either optimal (100) or nonoptimal (≤99) care in each of the three interpersonal domains.

Using analysis of variance (ANOVA), we found no evidence of clustering by data collection site. Moreover, bivariate analyses examining key variables by data collection site and health system type (Veterans Administration versus non-VA) showed no significant associations. Consequently, we did not include data collection site or health system variables in our final models.

Finally, we employed multivariable linear regression to examine the adjusted associations among patient assessment of physician communication, nursing care, and coordination/responsiveness of care and pain severity in three separate models.

Our study was approved by the CanCORS Steering Committee and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board. All analyses were conducted with Stata software (v. 13.0; StataCorp, 2013).

RESULTS

The analytic sample included 2,746 individuals, 51% of whom were male. The majority of participants were white (69%), followed by black (14%), and Hispanic/Latino (7%). Nearly a quarter of the sample (24%) had stage 4 disease at the time of survey administration. Further sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Analysis of patient responses to the three interpersonal domains of care has been reported previously (Ayanian et al., Reference Ayanian, Zaslavsky and Arora2010). Briefly, we found that 50% of patients rated their physician communication as nonoptimal, 54% rated their coordination/responsiveness of care as nonoptimal, and 28% rated their nursing care as nonoptimal. Further details on differences in ratings of interpersonal care by patient and health status characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Proportion of patients reporting less than optimal care, by sample characteristics (N = 2,746)

Table 3 presents unadjusted differences in mean pain severity scores by ratings of care and sample characteristics. Mean pain severity scores were significantly different between those individuals reporting nonoptimal care versus those reporting optimal care in the domains of physician communication (40.1 vs. 38.4, p = 0.020) and coordination/responsiveness of care (40.1 vs. 38.2, p = 0.009) but not nursing care. Mean pain severity differed by respondent race/ethnicity: scores ranged from 34.2 for API respondents to 45.0 for black respondents (p < 0.001). Scores also varied significantly by survey language: Mandarin survey respondents reported a mean pain severity score of 23.9 versus 39.1 for English respondents (p < 0.001). Individuals with depressed affect reported a mean pain severity score of 47.2 versus 36.5 among those without depressed affect (p < 0.001). We also observed significant differences in mean pain severity score by sex (p = 0.008), age (p < 0.001), marital status (p = 0.006), education (p < 0.001), wealth (p < 0.001), and cancer stage (p = 0.031). There was no difference in mean pain severity by cancer type in the unadjusted analysis.

Table 3. Mean BPI scores by sample characteristics and patient assessments of care

The three adjusted linear models examining the association between each patient-reported domain of interpersonal care and pain severity are presented in Table 4. In the model examining the adjusted association between physician communication and pain severity (model 1), rating physician communication as nonoptimal was associated with a 1.8-point higher average pain severity (on a 100-point scale) compared to those reporting optimal communication (p = 0.018). In the adjusted model examining the association between coordination/responsiveness of care and pain severity (model 2), rating care as nonoptimal was associated with a 2.2-point higher average pain severity compared to those reporting optimal coordination/responsiveness of care (p = 0.006). We found no significant association between ratings of nursing care and pain severity in the adjusted analysis (model 3).

Table 4. Multivariable linear regressions, patient assessments of interpersonal care and pain severity

Across the adjusted three models, lower pain scores were associated with younger age, more education, greater wealth, and Mandarin survey language. Higher pain scores were reported by black and multiracial participants and those with depressed affect.

The associations between black participant race/ethnicity and pain severity in the three adjusted models were particularly strong. Black participants rated their pain severity between 5.2 and 5.6 points higher on average than whites (p < 0.001 for all three models), as did multiracial participants (range: 5.4 to 5.6 points higher compared to whites; p < 0.010 for all three models). Presence of depressed affect was also strongly associated with pain severity. Scores ranged from 8.1 to 8.4 points higher for those with depressed affect compared to those without (p < 0.001 for all models).

The only adjusted difference in pain severity that met our criteria for minimally clinically important difference was for Mandarin survey respondents who reported average pain severity at 15.6–16.2 points lower compared to English survey respondents (p < 0.001 for all models).

As a sensitivity analysis, we ran all final models using a cutpoint of ≤90 instead of ≤99 in order to define nonoptimal care in each domain. This did not significantly alter the results.

DISCUSSION

In our study of colorectal and lung cancer patients reporting the presence of pain, we found small yet statistically significant associations between patient ratings of both physician communication/coordination and responsiveness of care and pain severity; however, patient race/ethnicity and depressed affect were more important factors in self-reported pain severity. We did not, find any association between patient assessment of nursing care and pain severity. While our outcomes suggest that interventions aimed at improving physician communication and coordination and responsiveness of care may result in improved cancer pain experience for some patients, differences in pain severity by ratings of interpersonal care in our study were extremely small and were not clinically meaningful.

We found significant differences in patient-reported pain severity by sociodemographic characteristics. Of note in our results were the large differences in pain severity between black and white participants in each of the assessment-of-care models, despite adjustment for patient ratings of care. Black/white disparities in cancer pain have been widely reported in the literature (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Richman and Hurley2002; Fisch et al., Reference Fisch, Lee and Weiss2012). Quality of care deficits, particularly around interpersonal communication, have been hypothesized to contribute to disparities in pain (Cintron & Morrison, Reference Cintron and Morrison2006). In our study, black participants rated care in each of the three interpersonal domains, including physician communication, better than whites, while rating pain severity significantly more severe. Yet, given the small size of the association we found between patient ratings of care and pain severity, our findings support the notion that patient variability in ratings of interpersonal care is only one of many factors affecting the cancer pain experience.

Patient-reported quality of care is increasingly being used to evaluate medical care, as well as to inform strategies and priorities for quality improvement (Dennison, Reference Dennison2002; Groene, Reference Groene2011). One hypothesis underlying the increasing use of these measures is that patient appraisals of care may relate to health outcomes through improved patient adherence to treatment (Dang et al., Reference Dang, Westbrook and Black2013; Isaac et al., Reference Isaac, Zaslavsky and Cleary2010). Some prior literature supports this association (Alazri & Neal, Reference Alazri and Neal2003; Fremont et al., Reference Fremont, Cleary and Hargraves2001; Safran et al., Reference Safran, Taira and Rogers1998). Yet, other recent work has questioned the relationship between patient satisfaction and health outcomes (Fenton et al., Reference Fenton, Jerant and Bertakis2012) and suggested that the observed associations in this domain may largely be explained by patient factors, rather than as a direct result of satisfaction (Jerant et al., Reference Jerant, Fenton and Bertakis2014).

Prior studies of the association between patient pain and satisfaction with care have also yielded mixed results. In fact, some studies have documented the phenomenon of a “pain paradox” wherein patients report very high satisfaction with care despite reporting a concurrently high pain burden (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Towsley and Berry2010; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Spross and Jablonski2002; McCracken et al., Reference McCracken, Klock and Mingay1997; Miaskowski et al., Reference Miaskowski, Nichols and Brody1994; Panteli & Patistea, Reference Panteli and Patistea2007). These studies have demonstrated that patient satisfaction among individuals experiencing pain is largely associated with interpersonal aspects of care, such as patient–provider communication (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Spross and Jablonski2002), or generally feeling “cared for” (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Towsley and Berry2010), rather than a reflection of their symptom experience. Moreover, satisfaction with pain management may be modulated by patient expectations about pain control (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Spross and Jablonski2002), suggesting that individuals with lower expectations for pain relief may report high satisfaction with care, despite experiencing high levels of pain. This may be particularly true for nonwhite patients or those of low socioeconomic status, who have been shown to have lower expectations for pain control in cancer (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Richman and Hurley2002).

Despite the challenges of using patient-reported measures of quality of care in this domain, cancer pain remains a common and problematic symptom experience, disproportionately experienced by certain patient groups. The findings from our study and others suggest that quality enhancement efforts to improve pain outcomes should consider including interventions to improve interpersonal cancer care, but also require other types of interventions.

Our study had several limitations. Patient-reported pain is the gold standard in pain assessment; however, prior research has demonstrated patient and group differences in underlying pain thresholds (Rahim-Williams et al., Reference Rahim-Williams, Riley and Williams2012) and expectations about pain management (Naveh et al., Reference Naveh, Leshem and Dror2011). Moreover, patient preferences for pain management vary, and some patients have been shown to be willing to tolerate higher levels of pain in order to avoid the side effects associated with pain medication (Gan et al., Reference Gan, Lubarsky and Flood2004). We were unable to measure patient pain thresholds, expectations about pain management, or patient satisfaction with pain control. Our findings were also limited by the fact that the survey instrument utilized to measure patient assessment of care was not specific to a particular provider. The patients in our study likely interacted with a number of providers, not all of whom were involved in pain management.

CONCLUSIONS

We found modest evidence that interventions targeting physician communication and coordination/responsiveness of care may improve pain burden in some groups of patients. However, differences in pain severity by ratings of care in these domains were not clinically significant. Further, we found large and significant differences in pain severity by survey language, race/ethnicity, and presence of depressed affect, despite controlling for a number of patient-reported sociodemographic and health status factors. Given the observed variability in both patient ratings of interpersonal care as well as patient pain severity, continued refinement of patient-reported measures of interpersonal care, with a particular focus on use of these measures among nonwhite patients and those with depressed affect, may be useful in improving the quality of life for cancer patients experiencing pain.