INTRODUCTION

Over the last 30 years, care for children with life-limiting conditions has grown from a hospital-based specialist model for children dying with cancer to the introduction of children's hospices to the provision of multidisciplinary community-based teams that provide care to children with long-term conditions and their families in the family home environment (Andrews & Hood, Reference Andrews and Hood2003). Indeed, as medical technology has improved, there has been a marked increase in the numbers of children with life-limiting conditions being managed in the community.

It is recognized that caring for any family member with a long-term medical condition within the home can be extremely demanding for the carers, often resulting in their mental health being compromised. Harding and Higginson (Reference Harding and Higginson2003) recently reviewed the adult literature that had addressed interventions to support carers. They discovered that carers involved with caring for a family member with palliative care needs have support needs of their own and experience considerable psychological effect. However, few targeted interventions were found to be reported in the literature. The interventions identified were mainly detailed in informative studies; they included home care nursing, respite services, social networks, problem solving, and group work. But there were few robust studies that discussed the effectiveness of such interventions.

Other studies have specifically focused on the well-being of parents. These have determined a set of essential contributing variables such as social support, coping strategy, and family dynamics (Patenaude & Last, Reference Patenaude and Last2001). Frank et al. (Reference Frank, Brown, Blaint and Bunke2001), in their research with parents of children with chronic illnesses, noted that affective responses in parents were associated with appraisals of stress, perceived social support networks, and the parent's perception of the child's adjustment to illness. In the case of children with life-limiting conditions, studies have tended to focus on mothers, and feelings of isolation and depression are commonly documented (Edmond & Eaton, Reference Edmond and Eaton2004). The aim of this study was to elucidate the lived experiences of parents of children with life-limiting conditions and, secondly, to consider the implications of these lived experiences for professionals.

METHOD

Participants

The first author had contact with the sample of parents through conducting a wider service evaluation study. Table 1 provides the characteristics of each participant. In presenting the data, participants are identified by pseudonyms.

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Design

This study uses van Manen's (Reference Van Manen1990) conceptualization of hermeneutic phenomenology that is both a research methodology and a method. In the context of research methodology, hermeneutic phenomenology refers to a certain theoretical philosophical framework in “pursuit of knowledge” (van Manen, Reference Van Manen1990, p. 28). The methodological premise of van Manen practices the philosophical belief that human knowledge and understanding can be gained from analyzing the prereflective descriptions of people who have lived the experience in question. In other words, the essence of the phenomenon is uncovered by gathering text from those living it and then interpreting this text (van Manen, Reference Van Manen1990, p. 7).

A convenience sample in West Yorkshire was achieved, and 10 interviews were conducted with parents of children with life-limiting conditions. Each interview lasted between 1 and 2.5 hours. The interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were encouraged to describe in their own words their lived experience of caring for their child with a life-limiting illness. The descriptions were discussed in length and related to specific meaningful episodes and events that had occurred prior to and since diagnosis. Clarifying questions were asked when needed to try and elucidate the experiences as deeply as possible, for example: (1) “Can you give me an example of this?” (2) “So what happened after that?” (3) “What do you mean by that?”

The phenomenological method's objective is to describe the full structure of an experience lived, or what that experience meant to those who lived it.

Ethical Considerations

The study was given local ethics committee and research and development approval. Participants were informed in writing and verbally that their participation was voluntary and confidential. During the interview an open attitude and a degree of sensitivity was needed to try and put the participants at ease, as they sometimes found themselves reliving challenging and upsetting past experiences.

Data Analysis

The phenomenological method necessitates a rigorous, step-by-step process of analysis of the life descriptions. At the outset, clarification is needed to detail that this inquiry used a research design and method that illustrates a close collaboration between the inquirer as a co-researcher and those with first-hand experience or knowledge. Although “special” language is used at base for design and methodological procedures, as an interpretive inquirer, in a way the first author simply watched, listened, asked, and recorded—with a commitment to the research question at all times. Here, the first author was acutely aware of Schwandt's (Reference Schwandt, Denzin and Lincoln1994) reflection that the interpretive researcher lives the question by a process of returning to the question or phenomenon until a sense of the nature of the topic being studied is felt.

Van Manen (Reference Van Manen1990, pp. 30–31) asserts that hermeneutic phenomenology is a dynamic interplay among six research activities:

1. Turning to a phenomenon that seriously interests us and commits us to the world

2. Investigating experience as we live it rather than as we conceptualize it

3. Reflecting on the essential themes that characterize the phenomenon

4. Describing the phenomenon through the art of writing and rewriting

5. Maintaining a strong and oriented relation to the phenomenon

6. Balancing the research context by considering [the] parts and [the] whole.

The purpose of these six activities is to assist a process in order to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of meaning of our everyday experiences.

The first author transcribed all the interviews and conducted a detailed analysis. Both authors then discussed the analysis and agreed on the given descriptions.

RESULTS

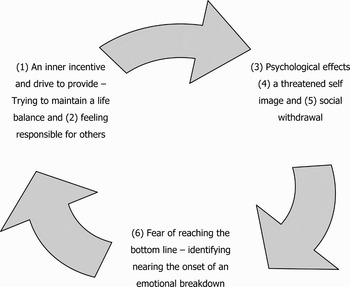

The essence of the lived experience of parenting a child with a life-limiting condition can be illuminated by six continuous constituents: inner drive, feeling responsible, psychological effects, threatened self image, social withdrawal, and fear of reaching the bottom line (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. General structure of the lived experience of parenting a child with a life-limiting condition.

Inner Drive

These parents discussed events that were characterized by their “inner incentives” and drives to provide for their ill children, to give their child the best possible quality of life they could. They described how knowing that they were putting full effort into caring for their child gave them a sense of satisfaction.

He cannot do things for himself. … He cannot do anything about his condition … and I do not want to be thinking after he has gone, well, I wish I had done this and I wish I had done that, because you cannot change things then, … so as long as I know that I have given him the best quality of life he could have possibly had, then I have nothing to reproach myself for later. (Haley)

These inner incentives were borne out of fighting for statutory provision: “We have become quite expert at presenting cases. … On a positive note you do collect a lot of skills yourself on the way.” (Laura) and through trying to maintain all aspects of their life in a balance. For many parents the hard work and demands of their life had helped them to achieve a level of emotional balance. Keeping this balance involved trying to avoid ruminating on the emotional impact of the situation and the possible future. These parents described lives where they never stopped; they were always running from one task to another, often neglecting their own basic needs. It was almost as if, had they stopped, the full realization of the situation they were in would be too much to bear.

Feeling Responsible

Feeling responsible for everyone and everything was a common theme that permeated all interviews. Parents discussed events where they had forced themselves to try and fit more events in a day than was possible in order to try and keep everyone happy, to try to avoid a feeling of failure and failing others. Often trying to meet the demands of everything and everyone meant that less attention was focused not only on themselves but their close marital relationships. Sometimes “letting off steam” and releasing the stress of their responsibility was directed toward partners in temper and arguments.

If I have had a really bad day … my instinct when he comes in is attack, I need to scream at somebody and he knows, he does … but it does not make for a good relationship. (Amy)

Over time this repeated behavior had led to some couples getting to a point of mutual realization that they needed to share the burden more:

Then as he got more ill and needing constant care, I said, well, he will just have to sleep with me, … so when he was small it was ok because the three of us could get in; now we cannot so [husband] has to sleep in the spare bed and occasionally he will relieve me and he will let me get a couple of hours, you know when I get really tired. But he needs his sleep because he has got to work you see. … It is a huge problem for us, but there is nobody that can come in and give us the rest we need. (Clare)

And for others it had led to relationship breakdown: “That is why he left me; he couldn't cope with it all” (Mary).

Psychological Effects

Parents openly discussed psychological manifestations and distress. They explained situations where they had learned to be overtly patient as they screamed inside, as a tactic to receive better help or support, as screaming overtly had not helped them. Internally dealing with managing this patience and the general stressors of their lives was difficult and, as stated earlier, frustrations were often vented toward partners. Furthermore, emotional distress was evident when parents recounted events and discussed their worries in relation to anticipating the grief and future loss:

I were just sat on my own and I remember sitting there. … There were leaves falling off the trees and I can remember thinking all these trees are dying and [child] is going to die and I sat there planning her funeral. (Catherine)

Sleeping difficulties were evident, and some parents reported also having to carry out care duties throughout the night. This meant that for many parents their sleep would also be governed by the sleep patterns of their child or any outside help if they received it. This complication further added to the apparent total lack of control parents felt to have over their own lives. The general lack of control parents held over their situation and their child's illness was a source of deep upset:

Now [child] could not wish for a better daddy; he is absolutely brilliant with him, but the first few years were hard for [husband] coming ‘round to accepting “this is my son; this is how it is going to be and there is nothing we can do about it” that he could not cope with. (Haley)

For some parents, no matter how exhausted they were, they had no vision of discontinuing their role, as this was not a given choice. Life had become a set of duties that could not be reorganized irrespective of the prospect of a future emotional breakdown. Each parent had spent hours, days, and weeks fighting with the health care system and letting their energies be drained by it. Now, they continued their fight but were realistic in understanding the powers professionals had in light of the lack of available service provision. They had come to the understanding that they held the burden, no one cared as they did, and no one was available like they were.

Threatened Self-image

Participants described how work had previously been an important part of their lives and identity. As caring demands had increased, it had become necessary for these parents to leave their workplace to care full time for their child. Such decisions had been felt to be enforced, indicating a further loss of control over their own lives. Still, to maintain their identity, it was as if all their energies were focused on succeeding in caring and protecting and fighting for their child. “I don't have time for anyone else; it is as simple as that” (Adele). Parents felt threatened, but they were not going to lose their strong and able character, although it was focused down a different path.

Social Withdrawal

Over time it appears that the lifestyle of these parents necessitated a gradual cutting off from the outside world socially. This was not only enforced but helped them to maintain order and routine and to be able to focus all their efforts on care and family commitments and, to a degree, to also preserve some self-identity. The difficulty was that losing common interests with social companions meant letting go and moving on to new ways of being:

Our social life, I mean. I think people underestimate the impact that it has on your life; you are constricted in every way, in every sense of the word, you know, you are not able to go out, you are not able to function as a normal family. Your interactions with other people change, your social life, … it finishes. (Clare)

However, this intense focus on care duties made these parents at risk of neglecting the warning signs of overexertion. Socially withdrawing from comforting activities, which had previously shaped their character, had made them isolated and part of “the inner circle.” They found, increasingly, that if they communicated with people outside the family network, most often it would be another parent of a child with a life-limiting illness, with the subject of the conversations being care related. This also helped parents to mentally normalize their behavior and ways of life. But given the fact that their peers were going through similar struggles and stresses, it made it more difficult for these parents to recognize times where they really needed to rest and “shoulder the load.”

Fear of Reaching the Bottom Line

All participants described how, in various ways, they had at different times almost reached the bottom line, the bottom line being emotional breakdown. They discussed the endlessness of the inner pain and fight, which at times had gotten so severe that it had made them want to let go and break down:

I mean I have done it a few times, I have really thought all I need to do is kill us all, it would be finished, … and nobody would have to look after us and I am not leaving any pressure on anybody else; it is a sad way to look at life but that is the way it makes you feel. (Mary)

However, in these low times, further surges of strength would develop for their lives to continue and for them to relieve the struggles and stressors for the good of their child, to preserve self-identity and to maintain some control. Once parents stop this struggle, they make themselves susceptible to the emotional decline.

DISCUSSION

The essential meaning of the phenomenon “the lived experience of parenting a child with a life-limiting condition” covers a multitude of facets. Therefore, here we have focused upon themes pertaining to the mental health of the parent. Within this realm, the life of a parent of a child with a life-limiting condition is understood as a life of feeling trapped, with an endless list of demanding challenges, as living with a drive for equity of care and support for their ill child and holding additional family and (for some) work responsibilities and demands. As long as attention is given to each challenge or that there is a hope of a healthy balance of tasks, where there is sufficient expert assistance or social support received, then motivation can be gained for the parent to continue in their caring role. Parents here are trying to maintain a balance on a narrow edge to meet the responsibilities they feel they have as a parent toward their ill child and to other family, friends, and work. This also makes the parent vulnerable to events where they also want to try and protect their threatened self-image, as individuals with their own wants and needs. However, cutting off from social activities and striving to get the best health care and support for their child leads to them neglecting their own essential needs, promoting energy drain, as well as feelings of guilt toward oneself, family, and others. Emerging psychological manifestations and overwhelming fatigue leads to a feeling of being trapped in a vicious circle, anticipating grief without a means to change any outcomes, culminating in a fear of reaching the bottom line. Indeed, there was a realization that, through all the struggles they face, there were times where emotional breakdown was in view. An acceptance that one cannot be all to everyone, stopping the mental struggle and letting go to enable motivation to rekindle, marked the turning of the tide and a return to the cycle of events that are at the core of maintaining mental health in life being a parent of a child with a life-limiting condition.

A general structure of the mental health realm of the lived experience of parents with a child with a life-limiting condition emerged from the descriptions (Figure 1). Here, participants described how they had to redirect all their consciousness toward their caring responsibilities, family, and/or other commitments in their lives to create a sense of meaning in their lives. Finding themselves trapped between demanding challenges and never-ending and conflicting demands produced an “inner incentive” forcing them to try and focus even harder on their responsibilities and their capacity to cope with their enduring stressors. Keeping up the fight provided protection against emotional breakdown. “Socially cutting off” was a means to protect the threatened self-image in a state of vulnerability and reduced strength for these participants. Accordingly, there is a need for a better understanding of the defense of “cutting off” and how to reach behind this defense and help the person to open up for “psychological support and acceptance of the struggle.” It is essential for mental health professionals to learn to engage and help with the care and support of families enduring the stress of caring for a child with a life-limiting condition.

Limitations

The goal of all phenomenological studies is to understand individuals’ unique lived experiences and not to reduce such to fragments in order to identify cause-and-effect relationships (Dahlberg et al., Reference Dahlberg, Drew and Mystrom2001). The study was limited to 10 participants, and it could be argued that the outcome of such research does not apply to other individuals' lives in other situations. Nevertheless, in researching the unique, a nonvariant essence among the sample emerged. The aim of qualitative research is not to reach generalizable findings but to enable a deeper understanding of the participant's lived experience of the phenomena under study. In this sense, this study of the experiences of 10 participants provided an understanding of the mental health realm of the lived experience of parenting a child with a life-limiting condition. These deeper understandings may be transferable to other settings and groups (Polit & Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2004).

Conclusion

This study revealed that the lived experience of parenting a child with a life-limiting condition feels like a never-ending struggle. Most services are in place to provide medical interventions and, at best, respite care. Very little attention is focused upon the wider issues of a parent dealing with caring for a child with a life-limiting condition, parents having to change their pattern of life and relationships and being able to cope with these enforced changes. Anticipatory grief and all the emotions coupled with grief, the anger, upset, and frustration, are all emotional needs that have to be channeled for these parents to be able to care and cope in times where hands-on provision is not available.

From a service development perspective, this study emphasizes that there needs to be more monies available for this patient group and an acknowledgement of the potential psychological consequences that can occur for parents. Appropriate psychosocial support interventions need to be available so that they can be implemented at an early stage (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Brown, Blaint and Bunke2001; Patenaude & Last, Reference Patenaude and Last2001). There is also scope for a longitudinal cost-effectiveness study to evolve from this work. Health care services that save money in the first instance by not implementing sufficient services on a medical, psychological, and social basis for children with life-limiting conditions and their families may eventually discover increased spending through adult mental health services having to pick up the pieces.