Introduction

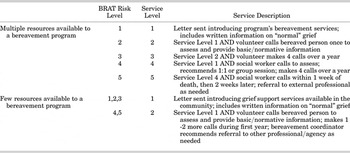

Risk assessment is seen as an important first step in determining the need for bereavement services and targeting services to those in most need (Aranda & Milne, Reference Aranda and Milne2000). The call for reliable and valid assessment tools is frequently cited in the literature as integral to a larger commitment to standards of bereavement care and hospice palliative care overall (Bromberg & Higginson, Reference Bromberg and Higginson1996; Keegan, Reference Keegan2002). To this end, the Bereavement Risk Assessment Tool, or BRAT, (Figure 1) was developed 1) to improve our ability to predict difficulties and complications for bereaved persons through timely and comprehensive assessment; 2) to standardize language and enhance communication among team members, and; 3) to improve the efficiency and consistency in the allocation of bereavement services.

Fig. 1. Bereavement Risk Assessment Tool (BRAT).

In hospice palliative care, the collection of personal, interpersonal, and circumstantial information of patients, caregivers, and family members begins prior to the death. Because it is not always possible to assess family members and their needs after the death, it can be particularly useful at the initiation of bereavement services when potential difficulties are already noted in a consistent and organized manner. Identifying concerns pre-death can also prompt earlier interventions that may benefit families and help them avoid some bereavement difficulties altogether.

Complicated Grief

The majority of current thinking tends to recognize grief as a multifaceted experience, encompassing complex interrelationships with other phenomena (Busch, Reference Busch2001; Stroebe et al., Reference Stroebe, Folkman, Hansson and Schut2006). It can be said that most people cope with the death of someone close to them reasonably well without any intervention (Aranda & Milne, Reference Aranda and Milne2000; Hogan, Greenfield, & Schmidt, Reference Hogan, Greenfield and Schmidt2001). For some, relatively simple actions such as the provision of information regarding normal grief experiences are sufficient (Boelen, van den Bout, & van den Hout, Reference Boelen, van den Bout and van den Hout2006). Approximately 10 to 20 percent of the bereaved population, however, are identified as having a more complicated grief reaction and may benefit from professional intervention (Prigerson & Jacobs, Reference Prigerson, Jacobs, Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001; Stroebe, Schut & Stroebe, Reference Stroebe, Schut and Stroebe2007).

Recently, the term complicated grief has received more focused attention in the literature. Stroebe et al. (Reference Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001) define complicated grief as the presence of a single or group of grief symptoms that deviate from the cultural norm in persistence and intensity and go on to consider nine identifying symptoms or factors. While intrusive or compelling thoughts of, or pining for, the deceased may feel devastating for a bereaved person, factors such as these are only considered significant when they persist over time or they significantly intrude on the person's daily life (Prigerson & Maciejewski, Reference Prigerson and Maciejewski2005).

Complicated grief has also been identified as a form of attachment disturbance which results in an unstable sense of self and relationship to others (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Shear and Frank1997). People who suffer from complicated grief are less likely to access professional help, placing them at even higher risk (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Silverman, Jacobs, Maciejewski, Kasl and Rosenheck2001). Prigerson and colleagues (Zhang, El-Jawahri, & Prigerson, Reference Zhang, El-Jawahri and Prigerson2006; Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Aslan and Goodkin2009) believe this classification of grief is clinically distinct from depression, anxiety, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), although they suggest these phenomena may co-exist. It has further been proposed that complicated grief be renamed Prolonged Grief Disorder and be included in the 5th revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Bereavement Risk

Aranda and Milne (Reference Aranda and Milne2000) define bereavement risk as “the extent to which a person is susceptible to adverse outcomes associated with the loss of someone significant through death”. They further stipulate that “the identification of risk suggests the probability of adverse outcomes rather than an indication of cause and effect” (p. 8).

Stroebe et al. (Reference Stroebe, Folkman, Hansson and Schut2006) designed an integrative risk factor framework intended to improve the understanding of individual differences in adjustment to loss or death and the interaction between risk factors. They argue against examining any specific factor in isolation and suggest that the assessment of risk should include factors that mitigate future potential harm in the adjustment to loss. These protective factors acknowledge resiliencies and strengths and may suggest why people cope differently when experiencing similar circumstances. Unfortunately, few studies use an assessment model that includes both strengths and deficits (Aranda & Milne, Reference Aranda and Milne2000; Walsh-Burke, Reference Walsh-Burke2000) and consequently there is little empirical support as to the benefits of such an approach.

The BRAT

A selection of evidence-based research that highlights current thinking and understanding of bereavement risk and provides empirical support for all but 4 of the BRAT's risk indicators is listed in Table 1. These 4 items remain included in the tool based on the clinical experience of the team who developed the instrument. They are: “significant other with life-threatening illness/injury”; “cultural or language barriers to support”; "parent expresses concern regarding his/her ability to support child's grief"; and “significant anger with OUR hospice palliative care program”. The last indicator was included by the clinical team in order to quickly identify persons who expressed animosity towards the organization and who might consequently refuse support or believe that bereavement support would not be available to them as a result of their animosity. Further testing will need to address the validity and clinical benefit of these empirically unsubstantiated indicators as predictors of poor bereavement outcome.

Table 1. Support from the literature of BRAT's bereavement risk and positive outcome factors

Knowledge and understanding of the grief process, including bereavement risk, continues to be a relatively new field of study. In their review, Stroebe and Schut (Reference Stroebe, Schut and Neimeyer2001) write, “…there is still a great deal to criticize, and little to praise, in research on risk factors in bereavement outcome” (p. 366), and cite the absence of appropriate control groups as a major contributor. Not only are there disputes related to theoretical or professional paradigms (Archer, Reference Archer2001; Stroebe et al., Reference Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001), but the role of the bereaved themselves in determining what constitutes risk is unclear (Hogan et al., Reference Hogan, Greenfield and Schmidt2001).

The question of how to assess risk in a consistent manner that is theoretically and methodologically sound remains outstanding (Stroebe, Stroebe, & Schut, Reference Stroebe, Stroebe and Schut2003; Center for the Advancement of Health, 2004). Also at question is whether we measure risk only to determine complicated grief as defined above, or to determine a predisposition for depression, anxiety, or other health related issues.

One study reports a clinical bias towards using risk assessment instruments developed in-house in 87% of the American hospice organizations it surveyed (Demmer, Reference Demmer2003). Although a number of tools have been developed more formally, there appear to be limitations for most. For example, some lack predictive utility for bereavement outcomes, (Theut et al., Reference Theut, Jordan, Ross and Deutsch1991; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Baker, Matteis, Rosenthal and Ware2005). Other tools fail to consider the circumstances of the death (Levy, Reference Levy1991), the presence of addictions or previous losses (Parkes & Weiss, Reference Parkes and Weiss1983; Kristjanson et al., Reference Kristjanson, Cousins, Smith and Lewin2005), or physical, social, religious, and psychological factors (Prigerson & Jacobs, Reference Prigerson, Jacobs, Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe and Schut2001).

We suggest there is a need for a reliable and valid tool that measures potential for problems in bereavement, includes elements of risk and resiliency, provides an opportunity to identify these factors prior to the patient's death, and can be tailored to the resources and services of different organizations. This study begins the introduction of evidence with regard to the BRAT's inter-rater reliability along with a few foundational measures of validity.

Design and Method

The Tool

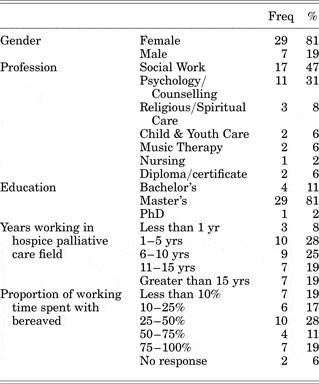

The BRAT is a 40-point list of both risk factors (36 items) and protective factors (4 items) that collectively predict the likelihood for difficulties or complications in bereavement. It was developed by a team of hospice palliative care clinicians comprising social workers, counsellors, psychologists, and child and youth specialists. Our psychosocial clinical team initially identified a list of factors believed to contribute to poor, exaggerated, or prolonged outcomes of grief. These factors were thematically organized and by consensus reduced to 36 independent items. Based on clinical experience, numerical values representing one of 5 levels of risk were assigned to each factor, reflecting greater or lesser relative risk. A range of total scores that identified 5 cumulative levels of risk was then identified. These levels of risk were designated as “no known risk” (level 1), “minimal risk” (level 2), “low risk” (level 3), “moderate risk” (level 4), and “high risk” (level 5)Footnote 1. To assist in the calculation of total scores, an Excel worksheet was developed to sum individual item scores and indicate the corresponding level of risk of the total score. Finally, the organizations’ bereavement team identified “default” servicesFootnote 2 to correspond with each of the BRAT's 5 levels of risk. Table 2 provides examples of how a bereavement program might offer services in relation to the risk levels identified by the BRAT.

Table 2. Examples of default bereavement service assignment matched with BRAT risk level

The tool was incorporated into clinical practice in 2003 and was revised in 2006 based on its use and an extensive review of the literature for both theoretical and empirical underpinnings. Some factors were re-worded for clarity, adjustments were made to the weighting of several factors and the 4 protective factors were added. A manual was developed to provide users with guidelines on using the tool and suggestions for incorporating it into a hospice palliative care bereavement program. Information on how to obtain a copy of the BRAT manual is available from Victoria Hospice (http://www.victoriahospice.org).

Methodology

The study design entailed asking participants to review 4 case studies containing 10 family members and caregivers of palliative patients. The case studies were created by 4 members of our clinical team with considerable experience in using the BRAT (hereafter referred to as the expert group). The case studies were based on actual patients and bereaved individuals and modified for anonymity. Thirty-one of the 40 BRAT itemsFootnote 3, as well as all 5 cumulative levels of risk, were represented in the descriptions of the 10 bereaved family members and their circumstances. The BRAT-determined risk levels were not revealed to the study participants; however, they were asked to provide a participant-estimated level of risk based on their own clinical experience using a 5-point scale identical to the risk levels of the BRAT. The cases were then tested in a pilot study and minor adjustments were made by the expert group to maximize the consistency of interpretation of the information provided.

Participants were recruited among social workers, professional counsellors, psychologists, and clergy who indicated they worked at least part-time with bereaved individuals. The Canadian Association of Social Workers, the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, the British Columbia Hospice Palliative Care Association, and the National Hospice Palliative Care Organization (USA) were approached and agreed to forward an invitation email to their members and/or place a description of the study on their website. Those professionals who replied were mailed a study package by our research assistant. The package included a consent form, instructions on how to use the BRAT including a detailed explanation of each factor, the case studies, BRAT forms, as well as a questionnaire requesting demographic information and feedback on their use of the tool. Participants were informed their responses would remain anonymous and participation in any or all of the study was voluntary. A pre-paid postage return envelope was also provided. In order to provide a comparison to participant responses, the expert group also completed BRATs on the 10 bereaved family members.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample. Reliability analyses were performed including intra-class correlations for absolute agreement of BRAT generated risk levels (McGraw & Wong, Reference McGraw and Wong1996). Inter-rater reliability of the individual items on the tool and the overall BRAT risk levels was assessed using Fleiss’ kappa, which is a generalization of Cohen's kappa to multiple raters (Fleiss, Reference Fleiss1971; Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977). Fleiss’ kappa provides a conservative measure of agreement (Strijbos et al., Reference Strijbos, Martens, Prins and Jochems2006) over that which would be expected by chance. Values close to 1.0 indicate excellent agreement. Comments from the questionnaires were coded and grouped for common words or phrases by three members of the research team.

Results

Respondents

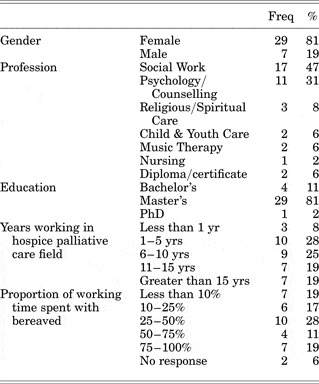

Fifty-four packages were sent out and 36 were returned. Of these, 18 were from Canada, 14 from the USA, and 4 were of unknown origin. Eleven respondents declined to indicate their age. Of the remaining 25, ages ranged from 31 to 74 years, with a mean of 52 (standard error 1.9) and median of 52. Additional participant demographics are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Participant Demographics (N = 36)

Inter-rater Agreement

For the 31 BRAT items used in this study, values of Fleiss’ kappa ranged from 0.05 to 0.97. Six items had kappa values less than 0.4 (slight to fair agreement) and the remaining 25 items (81%) had kappa values above 0.4 (moderate to almost perfect agreement) (Landis & Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977).

Table 4 provides the frequencies of the BRAT risk levels for each bereaved case. These BRAT risk levels demonstrated fair agreement with a kappa of 0.37 and an intra-class correlation of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.50–0.88).

Table 4. Frequency of BRAT risk levels by bereaved case including expert BRAT risk levels and participants’ percent agreement with the experts

Hypothesizing the participants’ BRAT risk levels would have higher agreement if using 2 levels of differentiation instead of 5, BRAT risk levels 1, 2 and 3 were collapsed into a Low risk category and levels 4 and 5 into a High risk category. Frequencies of percent agreement for Low/High risk levels are provided in Table 5. Fleiss’ kappa for the re-categorized data was 0.63, an improvement over that of the original scores. The intra-class correlation using 2 levels was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.47–0.87).

Table 5. Frequency of condensed* BRAT risk levels by bereaved case including the condensed expert BRAT risk levels and participants’ percent agreement with the experts

* Condensed BRAT risk levels condensed original BRAT levels 1, 2, and 3 into a Low category and BRAT levels 4 and 5 into a High category.

Validity

The original and collapsed BRAT risk levels were compared with the expert BRAT risk levels. Tables 2 and 3 also list percent agreement of participant BRAT risk levels with expert BRAT risk levels. The participant BRAT levels on the 5-point scale were in agreement with the expert levels 50 percent (average), whereas for the collapsed BRAT levels of Low/High, agreement was 87 percent (average). Participant-estimated levels of risk revealed only slight inter-rater agreement of 0.24 and ranged from 3 to 57 percent agreement with expert levels.

Thematic Analysis of Comments

Theme areas that arose in the analysis of questionnaire comments included ease of use, comprehensiveness, application and usefulness related to clinical practice, and limitations. Participants indicated the BRAT to be well organized and easy to use although there was a range of opinion regarding its length. Some participants found it quick and appreciated a one-page tool, while others found it long but wondered how to maintain its comprehensiveness in a shorter format. Many appreciated the inclusion of both protective and risk factors, along with the inclusion of specific areas of assessment, including spirituality, suicide risk, and culture.

Regarding clinical practice, the tool was thought to be useful for assessment and service delivery as well as training and advocacy. Participants acknowledged that the tool could not replace clinical judgment, but would be a resource or guiding instrument for the professional. A few participants thought they would use the tool as an adjunct resource in their practice or to supplement an existing tool.

There were a number of comments that reflected limited understanding and knowledge of the BRAT and its use, including questions about the calculation of risk levels, weighting of items and the definition of certain factors. Perceived limitations of the BRAT included subjectivity in identifying some factors, possible missing risk or protective factors and, as mentioned earlier, the large number of factors.

Discussion

The BRAT was designed with the following in mind: to assess and communicate information affecting bereavement; to predict the risk for difficult or complicated grief following death based on assessment prior to the death; to consider relevant resiliencies; and to assist in the efficacy and consistency of bereavement service allocation. The tool differentiates degrees of risk, considers the interaction of variables, and is amenable to the changing nature of the grief process. In these intentions, it seems the BRAT is somewhat unique.

The primary goal of this study was to estimate the inter-rater reliability of the tool. Using case studies, 36 psychosocial professionals with limited familiarity with the tool completed BRATs on 10 family members and caregivers of hospice palliative care patients. Perhaps due to this lack of familiarity, we found only fair agreement (kappa = 0.37) in their identification of levels of risk. The kappa value of agreement for factor selection was more encouraging, with 81 percent demonstrating moderate and above agreement. When risk levels were collapsed from 5 to 2, the kappa increased significantly to 0.63, indicating greater consistency in identifying low and high risk. Similarly, Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Nuamah, Lev and McCorkle1995), when evaluating the 8-item Bereavement Risk Index (BRI) which was designed to differentiate between low, moderate, and high levels of risk, also found discrimination between low and high levels only.

A noteworthy finding was that there was poor agreement for the participant-estimated level of risk based on their clinical judgement alone. It is possible that this particular group of professionals weighted these risk factors differently than the clinical team that developed the tool, or, more importantly, this may speak to the complexity of determining bereavement risk without the use of any tool and the potential for a wide interpretation of who is at risk without an anchoring structure.

The length and complexity of the tool poses several challenges. Some participants, in completing the BRAT, failed to include relevant information from the case studies. We hypothesize that keeping track of 40 potential indicators may be overwhelming for a new user and, therefore, would expect reliability to increase if these same professionals were to have further experience and familiarity with the tool.

As seen in Table 4, participant BRAT risk levels were in low agreement with the expert group in two cases (#5 and #8) with only 9 and 3 percent agreement, respectively. These cases involved a higher number of indicators causing us to speculate that lower agreement may be due to the complexity of these cases and the potential to miss or “sweep over” relevant indicators. This may also be the case for instances when there was a wide variance of risk, such as in case #9.

Some factors were simply misinterpreted. For example, one case study included a bereaved adult who had lost a parent. Death of a parent when the bereaved is an adult is not a BRAT item, yet, when completing the BRAT for this case, 2 participants marked the item “death of a parent, parental figure or sibling” which is listed under the heading “Children & Youth”. It appeared some participants also mistakenly identified factors related to the patient rather than to the bereaved.

A further limitation of the tool is the interpretation of unmarked indicators. A blank checkbox could mean the indicator is absent or that it has not been assessed. This ambiguity might be addressed by placing a checkmark beside the indicators that are present, marking an “X” beside the factors that are assessed but absent, and leaving the checkbox empty if the factor was not assessed. Although we believe bereavement assessment should attempt to include all of the BRAT's factors – not as a checklist per se, but as part of the overall intake and interaction with family members and caregivers during the care of the patient - this is not always achieved or possible. As an example, situations when patients are referred to a palliative care service only days prior to their death provides little opportunity to get to know family members and record pertinent bereavement risk information. We acknowledge that assessment is limited to information observed, solicited, or offered, and that our knowledge about clients at the best of times is imperfect and unfolding. Consequently, the BRAT is more likely to underestimate than overestimate risk.

The BRAT does not measure deeper psychological phenomena such as cognitive patterns, personality structure, or attachment styles, each of which have been identified as indicators of risk (Boelen, van den Bout, & van den Hout, Reference Boelen, van den Bout and van den Hout2003; Onrust & Cuijpers, Reference Onrust and Cuijpers2006; Schnider, Elhai, & Gray, Reference Schnider, Elhai and Gray2007). However, it can be used in conjuction with other tools that do measure these phenomena.

Limitations of the research study itself include the small sample size which affected our ability to statistically discriminate between 5 levels of risk. By not including 9 of the tool's 40 risk factors within the case studies, we did not acheive a complete testing of the tool, and the use of case studies rather than actual clients created some artificiality to the process. Although it would require a much more sophisticated and ethically sensitive methodology, testing the BRAT prospectively within a hospice palliative care program would be ideal. However, given some of the 40 items occur infrequently in practice, this may impede accumulation of a sufficient sample involving all of BRAT's items.

A review of the number of the BRAT's items seems warranted, including the 4 items that do not appear to have empirical support. However, in order to be useful to bereavement clinicians, we believe any reduction in the number of items must be weighed against the need for accuracy and comprehensiveness.

The literature and our experience both suggest there are many factors to be considered when assessing bereavement risk. While assessment is complex, it is critical in identifying those who may benefit from various kinds of bereavement support. We have provided evidence that a bereavement risk assessment tool offers advantages in identifying individuals at risk over clinical judgement alone. Some current tools, including the BRAT, show moderate reliability in assessing risk but only within wide parameters (low versus high). Multiple limitations of most of these tools remain. Future studies are needed in refining such tools, including their accuracy in identifying outcomes and best practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded in part by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Emerging team, the Victoria Foundation and the Victoria Hospice Society. We wish to thank the psychosocial team at Victoria Hospice and our research assistants, Stacey Slager and Jan Walker, for their contributions in this study.