Introduction

In June 2016, following the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada to legalize assistance in dying, the Canadian government enacted Bill C-14, which amended the federal Criminal Code and permitted Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) under certain conditions.

The road to legalization of MAID across Canada has largely focused on legislative details such as eligibility and establishment of regulatory clinical practice standards. As such, details on how to implement high-quality, person-centered MAID programs at the institutional level are lacking. With implementation left to the individual institutions or practitioners, there is a need to better understand opportunities for improvement that will minimize negative experiences for patients and family caregivers.

Prior international studies have examined patient perspectives regarding the choice to pursue MAID, understanding family caregiver role, or exploring clinician attitudes toward MAID (Ganzini et al., Reference Ganzini, Goy and Dobscha2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Price and Rayner2009; Nuhn et al., Reference Nuhn, Holmes and Kelly2018; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Harvath and Goy2015; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Wiebe and Nuhn2018; Wiebe et al. Reference Wiebe, Shaw and Green2018). Family member experience has also been evaluated (Dignitas, 2017; Gamondi et al., Reference Gamondi, Pott and Forbes2015, Reference Gamondi, Pott and Preston2018; Harrop et al., Reference Harrop, Morgan and Byrne2016; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Wiebe and Shaw2018; Swarte et al., Reference Swarte, van der Lee and van der Bom2003) and focused primarily on their journey toward MAID acceptance, the bereavement experience or their support need; however, few have studied this specifically to understand their views of potential quality gaps within the MAID process. Further, in Canada, there has been very little guidance on operationalizing a high-quality, patient- and family-centered MAID process at an institutional level. At the provincial level, to date, only Alberta has implemented a province-wide MAID program; therefore, it has largely fallen to individual institutions to design local MAID programs.

This study seeks to understand family caregiver perspectives of the MAID experience, as currently implemented at a large, urban academic health sciences center, and what improvement opportunities they might identify.

Methods

Study setting

This study took place at a large academic health sciences center in Ontario, Canada. Patients in either an inpatient or outpatient setting most commonly express a “desire to die statement,” which triggers an exploratory discussion with a member of their care team. Clinicians that are comfortable engaging in these exploratory discussions with patients seek to understand the patient's needs and provide information on available end-of-life options. For clinicians who are uncomfortable discussing all possible end-of-life options, including MAID, a referral can be made to the institution's ethicist who will facilitate a referral to a clinician that is willing and available to discuss with the patient. Thereafter, if the patient wishes to proceed with a written request, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario process map is followed, with the support of the institution's ethicist.

Study design and participants

This was a multi-methods study including a structured survey, focus group, and/or an unstructured e-mail/phone conversation. A family member (or another key contact) of patients who underwent MAID at our hospital between July 2016 and June 2017 were invited to participate. Family members were identified from the organizations database of MAID cases, which were maintained and secured by the ethics center. The database includes key contact information for patients and family caregivers who participated in the process. Non-English speakers were excluded.

Participants could contribute via a structured survey, a focus group, and/or unstructured e-mail/phone conversation. Data collection was facilitated by the principal investigator, a quality improvement professional with no direct involvement in the MAID processes. Additional facilitators were made available during the focus group.

A letter of invitation was mailed to eligible family members outlining the purpose and voluntary nature the study. Follow-up phone calls or e-mails were conducted to capture nonrespondents. Unstructured feedback was gathered via e-mail/phone for those who did not wish to participate via other methods.

The structured MAID quality survey was designed based on a prior, validated survey regarding end-of-life care experiences at our organization (Sadler et al., Reference Sadler, Hales and Xiong2014). This validated survey includes questions regarding patient and family-centered domains of care important at end of life, as identified in the literature (Teno et al., Reference Teno, Casey and Welch2001) and provided an evidence-based foundation for our structured MAID survey. Additional questions regarding MAID-specific processes and experiences were drawn from the “Seventh report on quality control of Dignitas’ services in relation to accompanied suicide” (Dignitas, 2017). The final survey was 30 questions. Because both the quantitative and qualitative questions were derived from previously validated tools, we did not pilot test with our study population.

The focus group used Experience-Based Design methodologies (Bate & Robert, Reference Bate and Robert2016) to capture the experiences of MAID family members (and patients) via an emotional mapping exercise (Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, Mackay and Smith2010). This methodology was selected because it is designed to plot participants’ positive and negative experiences in relation to a process/service and identifies where it must improve from the users’ point of view (Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, Mackay and Smith2010). It involves mapping emotions and trigger points onto a process map to better understand the participant experience. The mapping exercise was followed by a semistructured debrief and general group discussion, which were recorded. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim for analysis by an independent transcriptionist. Survey results, as well as e-mails and notes from telephone conversations, were transcribed for analysis.

This study was approved by the organization's Research Ethics Board (REB #232-2017) and all participants provided consent to participate.

Data analysis

Narrative data from the three participant sources (focus group, survey, and unstructured e-mail/phone conversations) were pooled by the principal investigator to enhance comprehensiveness of the data for thematic analysis. A qualitative, descriptive approach was used to derive themes as they emerged from the narrative data (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). Repetition and similarities/differences were used as theme-identification techniques (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays2000; Ryan & Bernard, Reference Ryan and Bernard2003).

Following thematic analysis, opportunities/themes were grouped into broader defined categories using a selective coding process. Because of the sensitive nature of the topic, the study team did not recontact participants to review the transcripts; however, if requested, they received a summary of any MAID process changes made.

Results

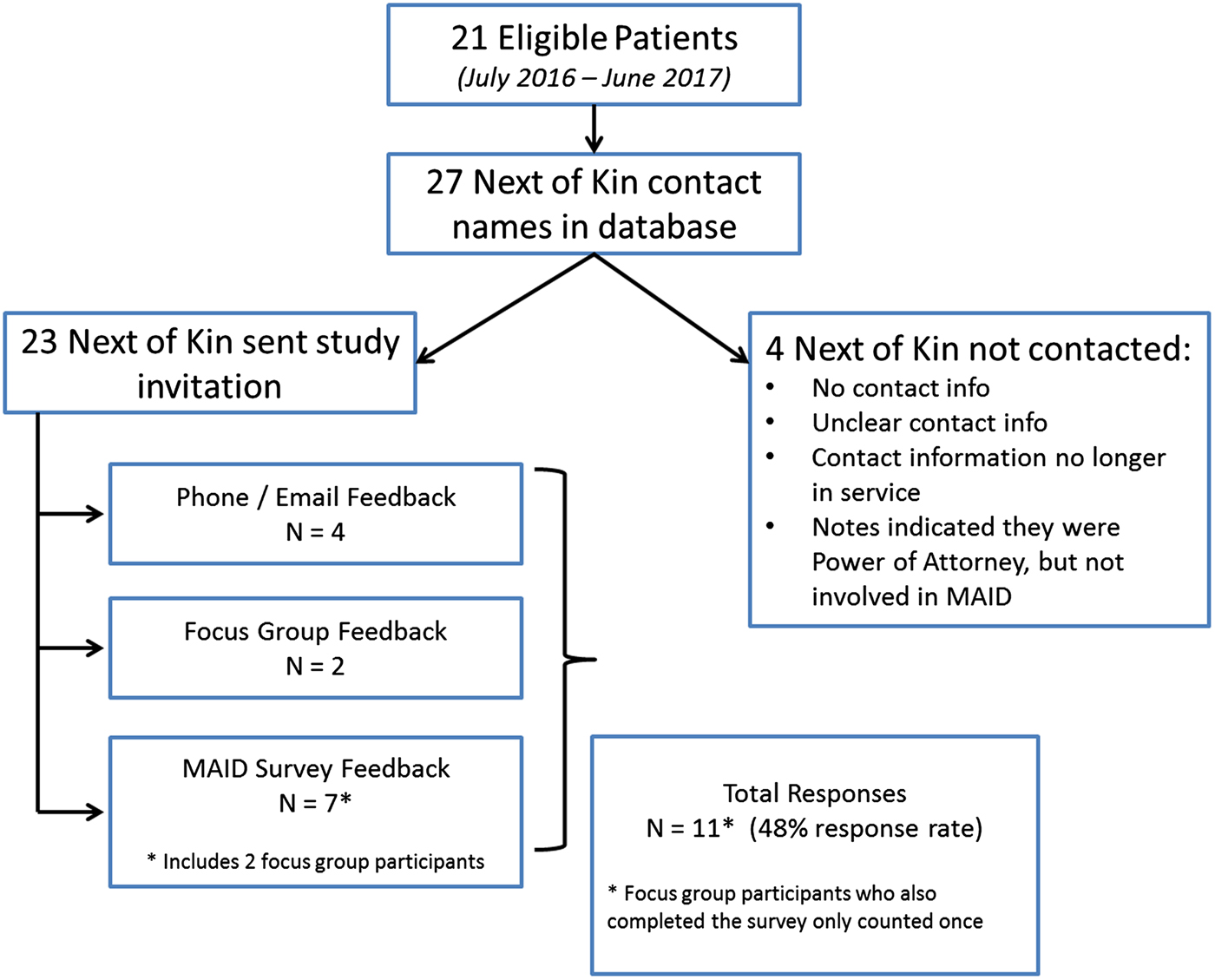

Of the 21 MAID deaths between July 2016 and June 2017, there were 27 eligible study participants (family/other). A detailed breakdown of invitations (and noninvitations) and responses is provided in Figure 1. Among 27 eligible participants, 23 were sent study invitations, and a total of 11 contributions representing unique patients were received (48% response rate) via the three methods for participation.

Fig. 1. Study response rates. MAID, Medical Assistance in Dying. NOK, Next of Kin.

Narrative data were specifically analyzed with a view to understand family perspectives of the MAID process. As such, emerging themes take the form of opportunities for change or improvement, as opposed to general patient/family experience themes. Positive experiences or feedback were not included as themes emerging from the data (because they do not reflect opportunities for improvement). Table 2 outlines illustrative comments from study participants.

Table 1. Available characteristics of respondents*

* Few participant characteristics are available because responses were anonymous and demographic details were not explicitly captured in the focus group.

Table 2. Illustrative comments by theme

MAID, Medical Assistance in Dying.

The improvement themes identified through participant feedback were grouped in two broad categories: operational and experiential aspects of the MAID process.

Operational improvement opportunities

Process clarity

Families reported that a lack of clarity regarding the MAID process led to unnecessary complexity and anxiety. In this most pervasive operational improvement theme, negative emotions were triggered during the initiation of the MAID request, where families expressed that they (or their loved ones) were unclear on how to make a request, how long it would take, and who they should approach. The latter was particularly relevant for inpatients that were unsure whether their current care providers would be involved and supportive.

There was a lack of clarity among respondents regarding who would be involved in the MAID process, including whether there was a “MAID team” to coordinate the process. Following the completion of MAID, the involvement of the coroner evoked a sense of “illegality” in the process for some families, and some found the involvement of organ and tissue donation professionals confusing and distressing.

Further aspects of process clarity pertained to MAID eligibility, as well as details regarding the medications that would be given, or how long families would have with their loved one following their death.

Scheduling challenges

Family members were distressed by challenges in the scheduling of MAID because of availability of space and human resources on their preferred date. Hospital occupancy and the availability of required clinicians often contributed to delays or rescheduling of the MAID procedure.

Ten-day period of reflection

The greatest source of negative emotion expressed by respondents was with respect to the mandatory 10-day period of reflection before the MAID procedure. Often described as “cruel,” families reported significant distress caused by this legal requirement, including anxiety about the potential loss of capacity of their loved one before the MAID procedure.

Experiential improvement opportunities

Clinician objection/judgment

Study participants often described feeling a sense of judgment and/or objection from care providers with respect to their loved ones’ decision to pursue MAID. Respondents reported that frequent repetition of similar questions from clinicians and the often-critical tone of those conversations were often perceived as “hurtful roadblocks” in an emotionally charged process. Families of inpatients who underwent MAID reported a perceived change in approach from the patient's care team following their expression of interest in MAID, with some providers being described as “cold” toward their loved one.

Patient and family privacy

The burden of keeping the decision to pursue MAID private added a layer of complexity to the experience, grief, and healing processes of many family members. Stress and anxiety around secrecy, while still engaging in logistical aspects of MAID and/or end-of-life care, were noted. Privacy was also raised with respect to location of MAID and patient identification within the hospital environment.

Bereavement resources

The final experiential improvement opportunity identified was in relation to nature and timing of the bereavement support provided to MAID families. Some indicated that support before and on the day of MAID was of utmost importance, particularly for inpatients and those who felt they grieved more before the procedure, rather than after. Further comments highlighted challenges with proximity of bereavement supports to their home following MAID, because they felt it too difficult to return to the location of their loved ones’ death (emotionally and logistically).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first time that Canadian family caregivers’ perspectives on the quality of the MAID process have been explored. Although family member experiences have been described elsewhere (Dignitas, 2017; Gamondi et al., Reference Gamondi, Pott and Forbes2015, Reference Gamondi, Pott and Preston2018; Harrop et al., Reference Harrop, Morgan and Byrne2016; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Wiebe and Shaw2018), they have largely focused on understanding their unique role in navigating MAID with their loved one, the effect of MAID on family, and their bereavement and coping experiences. The findings of this study identify opportunities for improvement in the delivery of MAID in a hospital setting, as identified by those with lived experience.

Qualitative results of this study revealed opportunities for improvement related to both operational and experiential aspects of the MAID process across six themes. From an operational perspective, study participants struggled with lack of clarity surrounding the MAID process, the influence of hospital resources (beds and providers) on the timing and availability of MAID, and the highly challenging nature of the 10-day period of reflection. With respect to process clarity, although patients and families can be directed to general Canadian support literature (Bridge C-14, 2018; Dying with Dignity Canada, 2015), the logistics of navigating the MAID process varies by province, region, or city, and even by organization. National or provincial resources cannot provide the specific operational details families may need to understand the local implementation of MAID process. They must therefore be provided with organization or region-specific process maps that include specific information regarding how to initiate a MAID request, what to expect throughout the process, who will be involved, and what supports are available to them at each step. One such example of site-specific support is the “Death with Dignity” program in a Seattle cancer center, where a patient advocate is assigned to help navigate the steps involved in their assisted dying process (Loggers et al., Reference Loggers, Starks and Shannon-Dudley2013).

Regarding the other operational improvement opportunities, given that the availability of MAID human and material resources and the mandatory 10-day period of reflection cannot easily be influenced, details regarding these potential roadblocks should be outlined along with alternative strategies and supportive resources available. Although a period of reflection is a common element of assisted death processes in every North American jurisdiction, with ranges of 48 hours to 15 days (Emanuel et al., Reference Emanuel, Onwuteaka-Philipsen and Unwin2016), we found no readily available literature describing support for patients and families for this unique period.

Families also highlighted several improvement opportunities with respect to how they experience the MAID process. Influencers of their experience included clinicians’ attitudes toward MAID, secrecy surrounding the MAID process, and how/when bereavement resources are made available to them.

The effect of clinician objection or judgment has not specifically been explored as part of the family caregiver or patient experience with MAID. The paucity of research in this area may be due to the variation in models across jurisdictions, where the setting (home vs. hospital) or method (patient vs. provider administered) of the assisted death may require little to no interaction with objecting clinicians. For example, Gamondi et al. (Reference Gamondi, Pott and Preston2018) describe the perception that assisted suicide in Switzerland does not belong to the medical community, but rather belongs in the private or civil milieu, which may provide a level of autonomy that minimizes the effect that clinician objection or judgment can have on family caregiver experience. In the Canadian context, however, patients may be seeking MAID while admitted to a clinical institution where the providers or organization conscientiously object to MAID. The finding that clinician judgment regarding MAID requests can negatively influence patient and family caregiver experience may be of particular relevance in helping organizations determine the best model for the delivery of patient- and family-centered MAID within environments where conscientious objection is permitted.

The timing and location of bereavement support are relevant in the Canadian context, where access to MAID may be limited in specific regions, particularly rural or isolated areas, requiring MAID-seekers to travel further from home. This could potentially make access to post-MAID bereavement support more challenging. Further, bereavement support is made more complex for those burdened by the need for secrecy despite the simultaneous need to attend to multiple logistical steps in assisting their loved one in accessing MAID (Gamondi et al., Reference Gamondi, Pott and Forbes2015). The challenge of the mandated 10-day wait period must also be considered when allocating predeath bereavement resources and developing support materials specific to the needs of MAID families.

Although there is great process variability across jurisdictions where assisted death has been legalized, many have adapted resources with broader applicability. There are many web-based resources to support families through all aspects of the assisted death process, developed by groups such as Dying with Dignity Canada, Bridge C-14 (Canada), or Death with Dignity (United States) that also include information for families related to grief and bereavement supports (Bridge C-14, 2018; Death with Dignity, 2018; Dying with Dignity Canada, 2015). However, most widely accessible online resources related to assisted death focus more on advocacy or creating awareness about assisted death policy and processes (Dignitas, 2018; Right to Die – Europe, 2018; Right to Die – Netherlands, 2018).

Given this diversity across jurisdictions (e.g., eligibility, setting, method, cultural specificities), patients and families experience of assisted death is at a very local level. As such, widely available resources must still be adapted to the local context to provide the degree of support necessary to positively influence their experience.

This study has several limitations. Study participants were from a single center, which may limit generalizability of our findings, particularly with respect to the nonhospital MAID experience; however, our institution provides approximately 7% of all hospital-based MAID in the province of Ontario. We therefore believe our sample strongly represents these family caregivers. Because non-English speakers were excluded, we are unable to determine whether language had any influence on the overall MAID experience. Results were aggregated, limiting the individual patient demographic data available; thus, we were unable to describe whether inpatients and outpatients who pursue MAID have differing experiences. Finally, narrative data were analyzed specifically from a quality improvement perspective and therefore did not focus on positive feedback during the theming exercise. Positive deviance is an important means of identifying high-quality practices that could be applied to other elements of the MAID experience (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Crurry and Ramanadhan2009).

The legalization of MAID in Canada has introduced a new pathway to patients at the end of life. Although practice standards have been made available to clinicians to ensure all legislated components of the MAID process are completed, detailed guidance for how to best implement patient- and family-centered MAID programs at the local organizational level are immature. This study provides guidance on improving the operational processes surrounding hospital-based MAID by identifying specific quality gaps in the experience of MAID patients and their family caregivers.

Family caregivers play a critical role in supporting patients to obtain MAID (Gamondi et al., Reference Gamondi, Pott and Preston2018) and, as such, their perspectives must be taken into account when creating guidelines or resources that support the formal legislated process (Gamondi et al., Reference Gamondi, Pott and Forbes2015). Future research in this area should focus on quality improvement interventions aimed at supporting families through the emotional challenges of the mandatory 10-day period of reflection, and the evaluation of strategies to minimize barriers to MAID such as timely and predictable access to providers and support resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Rob Fowler for his critical review of the draft manuscript, as well as Dr. Katie Dainty and Dr. Lesley Gotlib Conn for their qualitative research guidance and expertise.