Introduction

In 2015, approximately 17.5 million new cases of cancer were diagnosed worldwide, a 33% increase from 2005 that out-paced population growth (Fitzmaurice et al., Reference Fitzmaurice, Allen and Barber2017). Improvements in diagnostic methods and treatment effectiveness have contributed to substantial increases in the 5-year survival rate for all cancer types combined (OECD, 2013). Hence, there is a growing need for services to support individuals in facing the challenges of cancer survivorship.

Cancer survivors contend with various forms of distress, with severity ranging from expected reactions (e.g., worry and sadness) to symptoms that meet criteria for psychiatric disorders (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2019). Elevated levels of stress (Golden-Kreutz et al., Reference Golden-Kreutz, Thornton and Wells-Di Gregorio2005), fear of cancer recurrence (Simard et al., Reference Simard, Thewes and Humphris2013), and depression (Hinz et al., Reference Hinz, Krauss and Hauss2010) are problematic in cancer survivors. For example, as well as being at a greater risk of clinically significant depression than the general population, higher rates of sub-clinical levels of depressive symptoms have been reported among cancer patients (Linden et al., Reference Linden, Vodermaier and Mackenzie2012). Furthermore, many cancers and associated treatments alter bodily functioning and appearance; therefore, body image dissatisfaction may persist long into cancer survivorship (DeFrank et al., Reference DeFrank, Mehta and Stein2007; Cancer Australia, 2017). In addition, a systematic review of loneliness in cancer patients found that levels of loneliness increased, rather than abated, with time since diagnosis (Deckx et al., Reference Deckx, van den Akker and Buntinx2014). There is a pressing need for research on psychological constructs and associated interventions that may be beneficial to patients representing a broad range of cancer types who are experiencing varying levels and types of distress. Given their association with psychosocial wellbeing in various populations, including cancer patients (Khoury et al., Reference Khoury, Lecomte and Fortin2013; Przezdziecki et al., Reference Przezdziecki, Sherman and Baillie2013), the two constructs considered in the present study were mindfulness and self-compassion.

Mindfulness involves the self-regulation of attention directed to the present moment, with an orientation that reflects curiosity, openness, and acceptance (Bishop et al., Reference Bishop, Lau and Shapiro2004). Research in cancer patients has demonstrated the benefits of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) for reducing depression, stress, and fear of recurrence (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wen and Liu2015; Lengacher et al., Reference Lengacher, Reich and Paterson2016). Although research on the impact of MBIs on loneliness and body image concerns in cancer patients is lacking, studies in other populations have shown benefits (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Irwin and Burklund2012; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Lazarova and Schelhase2014).

Self-compassion has been defined as comprising three inter-related components: mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness (Neff, Reference Neff2003b). The mindfulness component refers to a balanced awareness of painful experiences, rather than mindfulness of all types of experiences, instead of over-identification with them (Neff, Reference Neff2003b). Common humanity recognizes that suffering is a part of the shared human experience, in contrast to feeling isolated during difficult times (Neff, Reference Neff2003b). Self-kindness refers to offering oneself acceptance and understanding, instead of negative self-judgment when experiencing difficulties (Neff, Reference Neff2003b).

Self-compassion has been found to be inversely related to depressive symptoms, stress, and body image dissatisfaction in cancer patients (Przezdziecki et al., Reference Przezdziecki, Sherman and Baillie2013; Pinto-Gouveia et al., Reference Pinto-Gouveia, Duarte and Matos2014; Sherman et al., Reference Sherman, Woon and French2017). Interventions designed to increase self-compassion in clinical and non-clinical populations have yielded improvements in these outcomes and constructs related to loneliness, such as social connectedness (e.g., Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013; Albertson et al., Reference Albertson, Neff and Dill-Shackleford2014; Bluth and Eisenlohr-Moul, Reference Bluth and Eisenlohr-Moul2017).

Given the loneliness reported by some cancer patients, group-based interventions may be well-suited to this population. Neff and Germer (Reference Neff and Germer2013) introduced the eight-week group-based Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) program, which has a central focus on cultivating self-compassion. In a randomized controlled trial of the MSC program in the USA general population, the intervention group reported significantly greater improvements than the control group in self-compassion, mindfulness, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, life satisfaction, and compassion for others (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013). In a randomized controlled trial of the MSC program in diabetes patients in New Zealand, self-compassion increased significantly, while depressive symptoms and diabetes-specific distress decreased significantly in the intervention group from pre- to post-intervention (Friis et al., Reference Friis, Johnson and Cutfield2016).

Given the established feasibility and acceptability of similarly structured eight-week group-based mindfulness programs (e.g., Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction [MBSR], Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy [MBCT]) in oncology populations (Shennan et al., Reference Shennan, Payne and Fenlon2011; Piet et al., Reference Piet, Würtzen and Zachariae2012) and the emerging benefits of self-compassion to the psychosocial wellbeing of cancer patients, the MSC program may be feasible, acceptable, and beneficial in this patient group. Although MSC is similarly structured to MBCT and MBSR, the content is substantially different (Germer and Neff, Reference Germer and Neff2013). For example, MSC differs from MBCT in that it is intended to be suitable for people with varying levels and types of distress (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013), whereas MBCT was developed to prevent relapse in individuals with a history of recurrent major depression (Segal et al., Reference Segal, Williams and Teasdale2002). Moreover, MSC has an explicit and central focus on self-compassion concepts and practices, with mindfulness of negative experiences regarded as a prerequisite to become aware of one's suffering and then respond with self-kindness and a sense of common humanity (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013). In contrast, MBCT and MBSR are centered on the cultivation of mindfulness of all types of experiences through meditation practices and do not emphasize self-kindness or common humanity (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013).

Over the past three decades, mindfulness interventions have shifted from relative obscurity to widespread acceptance and use in Western cultures and medical settings (e.g., Huang et al., Reference Huang, He and Wang2016; Kuyken et al., Reference Kuyken, Warren and Taylor2016). The same cannot yet be claimed about self-compassion interventions which, in Western cultures, may be misinterpreted as involving self-pity and self-indulgence (Neff Reference Neff2003b, Reference Neff, Germer and Seigel2012). Given the potential benefits of self-compassion interventions for cancer patients, however, it seems important to explore the acceptability and feasibility of the MSC program in Western cultural contexts.

Campo et al. (Reference Campo, Bluth and Santacroce2017) confirmed the feasibility of an abbreviated MSC program delivered by videoconference to 25 young adult cancer survivors, aged 18–29 years. Our search of PsycINFO and MEDLINE indicated that the face-to-face MSC program has not been examined in cancer survivors. Although face-to-face group-based programs may hold appeal in terms of reducing loneliness in cancer patients, barriers to participation may include difficulties in attending sessions scheduled at specific times and locations, as well as the fundamental appeal of a self-compassion program among the diverse population of cancer survivors. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of an adaptation of the face-to-face MSC program in a heterogeneous group of adult cancer survivors. A secondary aim was to provide preliminary estimates of pre–post-intervention effect sizes for symptoms of depression and stress, fear of cancer recurrence, loneliness, body image, self-compassion, and mindfulness.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees at the two participating health services. Participants were recruited from two oncology services in Melbourne, Australia. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were 18 years or older, had been diagnosed with non-advanced cancer within the past 6 months–5 years, resided within 60 km of the MSC group venue, were fluent in English, anticipated that they could attend at least four of the MSC group sessions, and were able to provide written informed consent. Non-advanced cancer was defined as any type of non-metastatic solid tumor cancer or a hematological malignancy anticipated to have a survival time exceeding 12 months. Individuals were ineligible to participate if they had a cognitive impairment that might interfere with engaging with the program.

Of the 173 eligible patients mailed a study invitation pack, 32 (19%) provided written consent to participate in the MSC program with 27 completing it (i.e., attending at least four sessions). Minimum attendance at four group sessions was consistent with protocols for trials of similarly structured eight-week MBIs (e.g., Shawyer et al., Reference Shawyer, Meadows and Judd2012). If patients were unable or unwilling to attend the program, they were asked to return an opt-out form if they did not consent to their medical records being accessed to enable a comparison of characteristics with those who completed the MSC program. Fourteen patients returned the opt-out form, leaving 127 in the comparison group. Table 1 presents medico-demographic information for those who completed the MSC program (program-completers) and the comparison group. Among the 27 program-completers, there was a wide age range (38–85 years), and most were born in Australia (85%) and had university educations (56%).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants who completed the MSC program (MSC-completers) and those who did not consent to the program (comparison group)

Other hematological, hematological malignancy other than lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

MSC, Mindful Self-Compassion.

a Participants who attended at least four Mindful Self-Compassion group sessions.

b All differences between the MSC-completers and the comparison group were non-significant (p > 0.05).

c Treatment categories are not mutually exclusive.

Procedure

Design

The research design involved the examination of recruitment data, MSC program attendance and attrition rates, program evaluation items, and differences in medico-demographic characteristics between program-completers and the comparison group. The study also included an examination of pre–post-intervention changes in psychosocial measures.

Recruitment

In contrast to studies of psychosocial interventions delivered at an individual level, a challenge of recruiting participants to group-based interventions is the requirement to recruit enough participants into each group by the pre-scheduled program start-dates. Based on our prior experience with recruiting cancer patients to other group-based psychosocial interventions, we decided to contact eligible patients through a series of postal mailouts until a maximum of 20 participants had been recruited into either of the two MSC groups. We also anticipated that inviting patients by post, rather than during clinical consultations, would reduce any perceived sense of obligation to participate that may have inflated recruitment rates. Similarly, patients who did not return a consent form were not sent a reminder letter as the aim of the study design was, as much as possible, to separate any sense of obligation to participate from a genuine interest in the MSC program.

Treating clinicians confirmed the eligibility of patients identified through clinical database searches prior to candidates being mailed a study pack. Participants received no remuneration for their involvement in the study.

Intervention

MSC is a manualized program delivered by certified teachers (Germer et al., Reference Germer, Neff, Becker and Hickman2016; Center for Mindful Self-Compassion, 2017a). To reduce burden in this patient group, the intervention used in the current study had an abbreviated session length, reduced from 150 to 105 min, and the mid-program 4-h retreat was omitted. Appendix 1 outlines the program structure used in this study. Participants were also encouraged to engage in a daily homework component of approximately 20 min of both informal and formal self-compassion and mindfulness practices. This included written reflective practices and guided meditations supported by audio-recordings made available by the program developers (Center for Mindful Self-Compassion, 2017b). To increase accessibility of the program, two separate groups were delivered—one on Friday afternoons and another on Saturday mornings. The venue was an education and research institute building, located within 6 km of both recruiting oncology services. All MSC sessions for both groups were facilitated by the second author who is a certified MSC teacher and a registered mental health clinician, with over 15 years of experience in delivering group-based mindfulness interventions. The first author was presented for all group sessions and recorded intervention fidelity.

Measures

Demographics

Medico-demographic characteristics were derived from medical records or a questionnaire completed by MSC participants at the beginning of the first group session.

Homework practice

Participants were provided with a log sheet to record time spent on self-compassion and mindfulness homework to provide an estimate of mean time spent daily on such practices throughout the program.

Feasibility and acceptability

Acceptability of the program to clinicians was determined by the proportion of clinicians approached who agreed to recruit patients to the study. Feasibility of the mail-out recruitment method was operationalized by the percentage of these clinicians who facilitated a mail-out. Acceptability of the program to invited patients was determined by the percentage of potential participants who consented to the program, with a target of 10–20%. Acceptability of the MSC program among those who commenced the program was assessed by retention rates, with a target of 70% of program commencers attending at least four group sessions. Acceptability was also measured using a MSC program evaluation form (MSCPEF; S. Hickman, Personal Communication, June 15, 2015), which was adapted for the cancer context and included in the questionnaire administered immediately after the final group session. The MSCPEF included eight quantitative items about various aspects of the MSC program. Anchors of 1 and 5 on the response scale indicated the worst and best outcomes, respectively. A 5-point Likert-scale item was also included to assess participants' perceptions of changes in their mental wellbeing from pre- to post-program and response options ranged from “much worse” to “much improved.” The instrument also included an item regarding acceptability of the program duration, with three response options: “preferred a shorter program,” “preferred a longer program,” and “program was right duration for me.”

Baseline and post-intervention measures completed by participants are listed below.

Depression and stress

The 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) were used to assess the symptoms of depression and stress experienced in the past week (Lovibond and Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995). The DASS-21 has demonstrated good validity and internal consistency (Gloster et al., Reference Gloster, Rhoades and Novy2008). The potential score range for each 7-item subscale is 0–42, with higher scores indicative of more frequent symptoms. Clinically significant symptoms (mild to extremely severe) are indicated by scores above 10 and 15 for the depression and stress subscales, respectively. Baseline and post-intervention Cronbach's alphas in the current study were 0.90 and 0.88 for depression and 0.84 and 0.84 for stress.

Fear of recurrence

The 9-item Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory-Short Form (FCRI-SF) was used to assess fear of cancer recurrence or progression (Simard and Savard, Reference Simard and Savard2015). This measure constitutes the severity subscale of the 42-item Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory and has demonstrated good internal consistency and convergent validity (Simard and Savard, Reference Simard and Savard2015). In the current study, baseline and post-intervention Cronbach's alpha were 0.90 and 0.89, respectively. Scores can range from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating greater fear levels and a threshold score of 13 indicating clinical levels of fear of recurrence (Simard and Savard, Reference Simard and Savard2015).

Loneliness

The 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3 was used to measure loneliness (Russell, Reference Russell1996). This instrument has demonstrated convergent validity with other measures of loneliness and acceptable test–retest reliability (r = 0.73) over 1 year (Russell, Reference Russell1996). Good to excellent internal consistency has been found in oncology samples (Deckx et al., Reference Deckx, van den Akker and Buntinx2014). In the current study, baseline and post-intervention Cronbach's alpha were 0.94 and 0.92, respectively. The potential score range is 20–80, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of loneliness (Russell, Reference Russell1996).

Body image

The 10-item Body Appreciation Scale (BAS) Version 2 has demonstrated sound psychometric properties (Tylka and Wood-Barcalow, Reference Tylka and Wood-Barcalow2015) and was used to assess body image. Cronbach's alphas for the current study were 0.94 and 0.89 for baseline and post-intervention scores, respectively. Scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more positive body image (Tylka and Wood-Barcalow, Reference Tylka and Wood-Barcalow2015).

Mindfulness

The Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R; Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Hayes and Kumar2007) is a 12-item measure. It has demonstrated convergent validity with other measures of mindfulness and acceptable to good internal consistency (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Hayes and Kumar2007). Cronbach's alphas for the current study were 0.82 and 0.84 for baseline and post-intervention, respectively. The potential score range is 12–48, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of mindfulness (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Hayes and Kumar2007).

Self-compassion

The 26-item Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) comprises six subscales that measure the positive and negative facets of the three self-compassion components: self-kindness vs. self-judgment, common humanity vs. isolation, and mindfulness vs. over-identification with painful thoughts and emotions (Neff, Reference Neff2003a). The SCS has demonstrated excellent test–retest reliability (r = 0.93) over a three-week period, as well as convergent and discriminant validity (Neff, Reference Neff2003a, Reference Neff2016). In the current study, Cronbach's alphas for the total scale were 0.95 and 0.92 at baseline and post-intervention, respectively. The possible score range is 1–5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of self-compassion.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to examine clinician support of recruitment and acceptability of the intervention to patients. Differences in medico-demographic factors between participants who attended at least four MSC group sessions (program-completers, n = 27) and those who did not consent to the program (comparison group, n = 127) were examined using Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests of independence for categorical variables. For the latter, response categories were collapsed where necessary to satisfy the Chi-square independence test assumption of a minimum expected cell count exceeding five (Gravetter and Wallnau, Reference Gravetter and Wallnau1996). This resulted in three dichotomous variables: religiosity (specified a religion vs. no specified religion), cancer category (hematological malignancy vs. non-hematological malignancy), and cohabitation (living with a partner vs. not living with a partner). For collapsed variables where expected cell counts still did not exceed 5, Fisher's exact test was used to examine group differences (IBM, 2016). A sensitivity analysis was conducted to compare medico-demographic factors between the 32 participants who consented to the program and the 127 participants in the comparison group. For all other analyses, data for the five individuals who consented to but did not complete the program were excluded. Changes in psychosocial measures from pre- to post-program for the 27 MSC-completers were examined using the paired-samples t-test or Wilcoxon-signed rank test, depending on whether change scores were normally distributed (Pallant, Reference Pallant2013). Effect sizes were estimated and interpreted using Cohen's d or  $r = z/\sqrt {\lpar {{\rm number\; of\; observations}} \rpar } $ as appropriate to the data distribution (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988; Pallant, Reference Pallant2013). A p-value of 0.05 was set for statistical significance.

$r = z/\sqrt {\lpar {{\rm number\; of\; observations}} \rpar } $ as appropriate to the data distribution (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988; Pallant, Reference Pallant2013). A p-value of 0.05 was set for statistical significance.

Results

Feasibility and acceptability

Seventeen clinicians were emailed information about the study and asked if they would recruit patients to the study; 13 (76%) agreed. Ten (77%) of these 13 clinicians facilitated a mail-out of study packs to eligible patients.

Of the 32 individuals who consented to the program, 30 commenced the program, with 27 completing it (i.e., attending at least four group sessions). Of the two people who consented to but did not commence the program, one was unable to commence because of hospitalization unrelated to cancer and the other could not be contacted before the program commenced. Reasons provided for withdrawing from the study by the three individuals who commenced but did not complete the program were physical illness unrelated to cancer (n = 1), family commitments (n = 1), and lack of interest in the program (n = 1).

Table 1 shows MSC session attendance and time spent on MSC home practices among those who completed the program. The mean number of group sessions attended by the 27 program-completers was 6.93 (SD 1.11). Intervention fidelity in both MSC groups was achieved, as all program elements for each of the eight group sessions were delivered by the trainer in a manner consistent with the MSC program manual (Germer et al., Reference Germer, Neff, Becker and Hickman2016).

There were no significant differences between the program-completers and the comparison group in relation to age, sex, cohabitation with a partner, religiosity, country of birth, cancer category (hematological vs. non-hematological), cancer treatment types, and distance from the MSC program venue. However, there was a trend toward a shorter time since diagnosis in the program-completers group (Mdn = 33 months) compared to the comparison group (Mdn = 41 months), U = 1,339.00, p = 0.074. Sensitivity analysis was undertaken with a comparison of medico-demographic factors for all 32 participants who consented to the MSC program against the comparison group. All differences remained non-significant, except for time since diagnosis. This was significantly lower among the 32 participants who consented to MSC (Mdn = 31.5 months) than the comparison group (Mdn = 41 months), U = 1,560.00, p = 0.043.

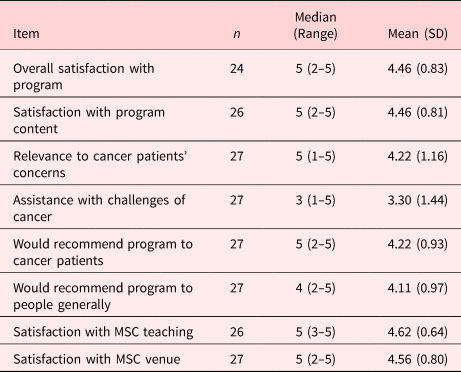

Table 2 shows results for the MSCPEF. Apart from the item on whether the program assisted with the challenges of cancer, satisfaction ratings for all other aspects of the program exceeded 4, where the possible range was 1–5. Twenty-three (85%) program-completers reported that the program was the right duration for them, while one (4%) participant reported a preference for a shorter program and three (11%) preferred a longer program.

Table 2. Responses to items on the MSCPEF

MSC, Mindful Self-Compassion program.

MSCPEF, Mindful Self-Compassion Program Evaluation Form.

Safety is a critical aspect of intervention acceptability. In relation to perceived change in mental wellbeing from pre- to post-program, 9 (33%) of program-completers reported “much improved” mental wellbeing, 8 (30%) reported “mildly improved” and 10 (37%) reported “much the same,” with none reporting “mildly worse” or “much worse” mental wellbeing. Furthermore, the proportion of program-completers who reported clinically significant symptoms of depression, stress, and fear of recurrence decreased from pre- to post-program: 44% to 19% for depression, 33% to 19% for stress, and 56% to 44% for fear of recurrence.

Changes in psychosocial measures from pre- to post-intervention

All pre–post changes on psychosocial measures were in the direction of improved wellbeing. As shown in Table 3, depressive symptoms, stress symptoms, fear of recurrence, loneliness, and isolation decreased significantly, while mindfulness increased significantly from pre- to post-MSC. Improvements included medium-sized effects for depressive symptoms, fear of recurrence, and mindfulness. Small effects were determined for stress, loneliness, body image satisfaction, and self-compassion.

Table 3. Changes in psychosocial measures from pre- to post-abbreviated MSC program

a Pre–post differences were examined using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon-signed rank test, as appropriate to the distribution.

b Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d or r, appropriate to the distribution. Unless otherwise denoted, Cohen's d is shown. Interpretation of Cohen's d: 0.20 = small, 0.50 = medium, 0.80 = large (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). Interpretation of r: 0.10 = small, 0.30 = medium, 0.50 = large (Pallant, Reference Pallant2013).

Discussion

This adaptation of the MSC program was found to be acceptable to treating clinicians, with 76% of those approached agreeing to support the recruitment of participants. Recruitment using a mail-out was feasible with 77% of these clinicians facilitating a mail-out, and 19% of patients consenting to participate in the MSC program. Acceptability of the intervention among those who commenced the program was demonstrated by a retention rate of 90%, with program-completers attending an average of seven of eight sessions. In prior research on the feasibility and acceptability of the MSC program, Bluth et al. (Reference Bluth, Gaylord and Campo2016) set a target of overall attendance at group sessions of 75%, and Campo et al. (Reference Campo, Bluth and Santacroce2017) specified acceptability as a minimum of 75% of participants attending at least six of the eight group sessions. Both these benchmarks were also achieved in the current study.

The acceptability of the program was also demonstrated by high ratings regarding content, teacher, venue, and the overall program. In addition, participants rated the program highly regarding its relevance to the concerns of cancer patients and the likelihood of recommending the program to other cancer patients. These findings suggest that, although MSC is a general program rather than cancer-specific, participants were able to transfer the skills and knowledge gained from the MSC program to their cancer experience. In relation to program safety, 63% of MSC-completers reported an improvement in mental wellbeing, and none reported deterioration. Moreover, changes in all psychosocial measures were in the desired direction.

The characteristics of participants who completed the MSC program indicate that the intervention was acceptable to a diverse sample, in terms of age, sex, and cancer type. Six types of cancer were represented among MSC-completers, with breast and lymphomas being most common.

In contrast to other studies of the MSC program (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013; Bluth et al., Reference Bluth, Gaylord and Campo2016; Campo et al., Reference Campo, Bluth and Santacroce2017), a unique aspect of this study was the examination of medico-demographic differences between those who completed the program and those who did not consent to the program. This analysis indicates that cancer patients who are closer to the time of diagnosis may be more likely to consent to the program. Nonetheless, there was a wide range in time since diagnosis (9–59 months) among program-completers. This highlights the importance of assessing psychosocial needs and providing appropriate interventions across the cancer trajectory. The lack of differences in other medico-demographic factors between MSC-completers and the comparison group indicates that age, sex, cohabitation status, country of birth, religiosity, diagnosis with hematological vs. non-hematological malignancy, and distance from venue did not influence the acceptability of the program. Accordingly, in any subsequent implementation of the MSC program in an oncology setting, it would seem reasonable to anticipate interest in the program from patients representing a broad range of medico-demographic factors.

Small-to-medium effects were found for depressive symptoms, stress symptoms, fear of recurrence, loneliness, mindfulness, and self-compassion. This study extends findings from prior research that the face-to-face MSC program was associated with improved psychosocial wellbeing in adults and adolescents in the general community (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013; Bluth et al., Reference Bluth, Gaylord and Campo2016) and patients with diabetes (Friis et al., Reference Friis, Johnson and Cutfield2016). Moreover, it builds on earlier research on another abbreviated MSC intervention delivered by video-teleconference to young adult cancer survivors (Campo et al., Reference Campo, Bluth and Santacroce2017). Consistent with earlier research, the MSC program was associated with significant reductions in symptoms of depression and stress and increases in mindfulness (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013; Bluth et al., Reference Bluth, Gaylord and Campo2016; Friis et al., Reference Friis, Johnson and Cutfield2016; Campo et al., Reference Campo, Bluth and Santacroce2017). There appears to have been no previous examination of the impact of the MSC program on stress and fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors. Nonetheless, the decrease in fear of recurrence found in the current study is consistent with prior research that demonstrated reductions in more general forms of anxiety in other populations following participation in the MSC program (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013; Bluth et al., Reference Bluth, Gaylord and Campo2016). While there appears to be no earlier studies on the impact of the MSC program on loneliness, the decrease found in the present study is consistent with Campo et al.'s finding of reduced social isolation in cancer survivors following participation in the program.

We found a small and non-significant effect for body image. In contrast, Campo et al. (Reference Campo, Bluth and Santacroce2017) found a large effect size (d = 1.39) for body image following an abbreviated MSC program in an all-female sample of cancer survivors. Studies on body image in cancer survivors have found that body image dissatisfaction is higher in women than men (Grant et al., Reference Grant, McMullen and Altschuler2011; Krok et al., Reference Krok, Baker and McMillan2013), consistent with findings in the general population (Algars et al., Reference Algars, Santtila and Varjonen2009). Accordingly, it may be that body image concerns were less salient in the current mixed-sex sample than the female samples studied in prior research on self-compassion interventions and body image.

Some effect sizes for comparable outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms, mindfulness, and self-compassion) were smaller than those found in research involving the full MSC program, which entailed 20 h of group-based sessions and a half-day retreat (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013). It is possible that the current smaller effects were partially attributable to delivering an abbreviated version of the program, i.e., 14 h of group-based sessions. Despite this smaller dose of the MSC program, only 11% of participants preferred a longer program. These results highlight the importance of finding a balance between acceptability of program duration and effect on psychosocial outcomes.

Limitations of this study should be considered in interpreting the results. The recruitment method might have influenced the apparent acceptability of the intervention in terms of the proportion of patients who consented to participate in the MSC program. Prior research has found that cancer patients who are invited by their treating clinicians to participate in research are more likely to do so than when other recruitment channels are employed (Michael et al., Reference Michael, O'Callaghan and Baird2015). Nevertheless, the use of posted letters, rather than a face-to-face request, may have ameliorated any effect of this factor in over-inflating the response rate. Other MSC studies used recruitment strategies (e.g., social media and flyers) that precluded establishing the response rate among those made aware of the study (Neff and Germer, Reference Neff and Germer2013; Bluth et al., Reference Bluth, Gaylord and Campo2016; Campo et al., Reference Campo, Bluth and Santacroce2017). Therefore, it is not possible to benchmark the enrollment rate in the current study against previous research on the MSC program.

Although the lack of screening for baseline distress was consistent with the objective of exploring the acceptability of the program to a heterogenous group of cancer patients, the inclusion of some participants without elevated baseline distress may have reduced observed effect sizes. Variation in baseline levels of distress among participants suggests that the program appealed to those with or without clinical levels of distress. This highlights the value of offering psychosocial interventions to cancer patients whose psychosocial needs may not be apparent when assessed using measures commonly used to determine distress. Furthermore, the acceptability of the program to individuals with or without clinical levels of distress may increase the feasibility in terms of enrolling enough participants for economically viable groups. This study lacked a control arm, and therefore pre–post-intervention changes in psychosocial measures cannot be attributed to the MSC program. Furthermore, although the observed pre–post changes are encouraging, effect size estimates should be interpreted cautiously, given the small sample. Properly powered randomized controlled trials with follow-up will be necessary to determine any benefits of the MSC program to cancer patients over a longer period. Given the lack of research on comparisons of MSC against MBCT or MBSR, the inclusion of one of the latter as a comparator arm seems worthwhile. Future research to elucidate the active components of the MSC program for target outcomes is also needed to determine which activities and exercises constitute the minimal dose for clinically meaningful improvements in psychosocial outcomes.

In conclusion, the present findings indicate that the adaptation of the MSC program is feasible and acceptable to cancer patients. Preliminary estimates of effect sizes in this heterogeneous sample of cancer survivors suggest that participation in the MSC program may be associated with improvements in psychosocial wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the 2015 Cabrini Foundation Clinical Research Grant Round. The Scientific Advisory Committee of the Psycho-oncology Co-operative Research Group (PoCoG) supported the development of this research. PoCoG is funded by Cancer Australia through their Support for Clinical Trials Funding Scheme. The authors also wish to thank the participants for their contribution to this study.

Conflict of interest

John Julian offers the MSC program through his private social work practice. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1 Program outline for an adaptation of the Mindful Self-Compassion program

SESSION 1 - Discovering Mindful Self-Compassion

SESSION 2 - Practicing Mindfulness

SESSION 3 - Practicing Loving-Kindness Meditation

SESSION 4 - Discovering Your Compassionate Self

SESSION 5 - Living Deeply

SESSION 6 - Managing Difficult Emotions

SESSION 7 - Transforming challenging relationships

SESSION 8 - Embracing Your Life