INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the most common cancer and leads to more cancer-related deaths than any other type of cancer (American Cancer Society, 2015). More than half (57%) of lung cancer patients are diagnosed at a later stage, and the one- and five-year survival rates are 26 and 4%, respectively (American Cancer Society, 2015). Moreover, the high recurrence rates make lung cancer a life-threatening disease (Ferrell et al., Reference Ferrell, Koczywas and Grannis2011). The adverse side effects of cancer treatments and poor prognosis lead lung cancer patients to experience the severe physical and psychosocial distress (Schofield et al., Reference Schofield, Ugalde and Carey2008). A supportive care program based on the palliative care model that addresses both symptom management and psychosocial care is therefore needed for the care of lung cancer patients.

Linden et al. (Reference Linden, Vodermaier and Mackenzie2012) reported that more lung cancer patients seek help for managing depressive symptoms at the first visit to the cancer center than do other types of cancer patients. Similarly, depressive symptoms have been reported more frequently by lung cancer patients compared to other cancer patients in the second week after surgery (Hong & Tian, Reference Hong and Tian2014). Park et al. (Reference Park, Kang and Hwang2016) found that significant numbers of lung cancer patients suffer from depressive disorders postsurgery compared to presurgery. At 12 months post-diagnosis, lung cancer survivors have been consistently identified as the group at highest risk for depression compared to all other groups of cancer survivors (Boyes et al., Reference Boyes, Girgis and D'Este2013). These results suggest that depression is a common form of psychological distress among lung cancer patients as a result of active cancer treatment during posttreatment survivorship.

More severe depressive symptoms have been associated with worse survival rates and mortality rates in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (Arrieta et al., Reference Arrieta, Angulo and Nunez-Valencia2013; Pirl et al., Reference Pirl, Greer and Traeger2012; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Ganzini and Duckart2014; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Sawhney and Hansen2013). Moreover, depressive symptoms have also been found to correlate with lung cancer patients' noncompliance with regular follow-ups for cancer surveillance screening, poor quality of life, poor motivation for self-care, and a lack of healthy behaviors (e.g., inactivity and refusing to stop smoking) (J. Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li and Cui2015; Maliski et al., Reference Maliski, Sarna and Evangelista2003; Pirl et al., Reference Pirl, Greer and Traeger2012; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Ganzini and Duckart2014). Patients suffering from depression also cause considerable psychological burden for their family members (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Duberstein and Sorensen2005). Ferrell et al. (Reference Ferrell, Koczywas and Grannis2011) indicated that an active style of coping with depression is associated with longer survival among lung cancer patients. It is therefore prudent to develop effective supportive care interventions in order to reduce depressive symptoms among lung cancer patients.

A systematic review by Walker et al. (Reference Walker, Sawhney and Hansen2013) examined the effects of psychological interventions on depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients. Their results indicated that, compared with standard care, additional psychological interventions can improve depressive symptoms. However, these effects need to be confirmed via a metaanalytic study. The present review was mainly focused on interventions that took a psychological approach. In addition to psychological factors (Haun et al., Reference Haun, Sklenarova and Villalobos2014; Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Papadopoulou and Kotronoulas2013), physical factors were also associated with depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients. Physical distress (related to breathlessness, fatigue, insomnia, cough, and alopecia) has been found to be significantly associated with depressive symptoms among lung cancer patients (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Liao and Shun2011; Maneeton et al., Reference Maneeton, Maneeton and Reungyos2014). Another study found that dyspnea and respiratory problems commonly increase anxiety and depressive symptoms in lung cancer survivors (Vijayvergia et al., Reference Vijayvergia, Shah and Denlinger2015). Good-quality supportive care programs based on the palliative care model need to include both physical symptom management and psychological care to address common physical distress (e.g., pulmonary dysfunction and psychological/social/spiritual distress) in lung cancer patients (Ferrell et al., Reference Ferrell, Koczywas and Grannis2011). Therefore, a comprehensive review would need to include both body and mind interventions that target the physical and psychological factors that contribute to depression in lung cancer patients.

We conducted a metaanalysis to evaluate the overall effect of supportive care interventions that aimed to manage the physical and psychological causes of depressive symptoms among lung cancer patients, and to find out whether overall effect size and study design were modified by population and treatment factors.

METHODS

Criteria for Considering Studies for Our Review

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that aimed to compare a supportive care intervention with standard care for lung cancer patients. Studies were eligible if they were written in English or Chinese, were published as original articles in a peer-reviewed journal, and offered results that reported effect size. Studies were excluded when the data on their lung cancer patients were not provided separately.

Lung cancer patients with small-cell and non-small-cell cancer, at different cancer stages, under different treatments regimes, undergoing active cancer treatment, or in posttreatment cancer survivorship were included as participants. A concurrent diagnosis of another physical disease was not a criterion for exclusion.

We defined supportive care interventions as noninvasive and nonpharmacological interventions that promoted and maintained well-being, and that enhanced patients' capacity to cope with symptom distress and adjustment problems related to living with cancer (Molassiotis et al., Reference Molassiotis, Uyterlinde and Hollen2015a ). Supportive care interventions with both physical and psychological types of interventions were included. The main outcome of our study was depressive symptoms measured by well-validated questionnaires.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

The following databases were searched from their inception until September of 2015: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, and the Chinese Electronic Periodical Services (CEPS). We employed the following search strategy: Lung Neoplasms [Mesh] OR Small Cell Lung Carcinoma [Mesh] OR Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung [Mesh] AND Depressive Disorder, Major [Mesh] OR Depression [Mesh] OR Depressive Disorder [Mesh]. The reference lists of relevant articles were also screened.

Data Extraction and Management

Two review authors extracted data using a standardized form, which included information about study design, participant characteristics, descriptions of the intervention, and outcome measurements. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or, where necessary, using a third review author. We also contacted the authors of some of the studies to obtain missing data. We excluded data if the authors were unable to provide such data (means and standard deviations of depressive scores) or if they did not respond to our emails.

Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for included studies using the criteria of quality assessment recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2011). We evaluated the following domains: random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (detection bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting of outcomes (reporting bias), and other biases (e.g. sponsorship bias). To determine the risk of bias for each study, a quality rating from “unclear risk of bias,” to “low risk of bias,” to “high risk of bias” was utilized according to the presence of sufficient information and potential bias.

Data Synthesis

We employed Review Manager software (v. 5.3; the Cochrane Community, London) to conduct statistical analyses and generate forest plots. A random-effects model was used to calculate pooled effect size estimates. All the studies in our review measured depressive symptoms, but they utilized different depressive scales. The standardized mean difference (SMD) test was used to measure treatment effects when studies assessed the same outcome but used different scales (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2011). We therefore calculated SMDs (Cohen's d) with their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI 95%) for each study to estimate treatment effects. A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Following the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, we analyzed all participants who completed and dropped out of the study. Heterogeneity was evaluated using I 2 statistics to assess how much variance between studies could be attributed to differences between studies rather than chance.

In order to explore the potential moderating factors for heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was conducted to examine whether the overall effect size was modified by the study design, cancer types, cancer stages, baseline severity of depression, intervention types, intervention durations, intervention sessions, or intervention formats. We also conducted sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the results of our metaanalysis with respect to the following decisions made in the process of obtaining data: (1) small sample size (<50); (2) inadequate sequence generation; (3) inadequate concealment of allocation; (4) nonblinded outcome evaluation; and (5) incomplete outcome data (as-treated analysis).

RESULTS

Study Selection

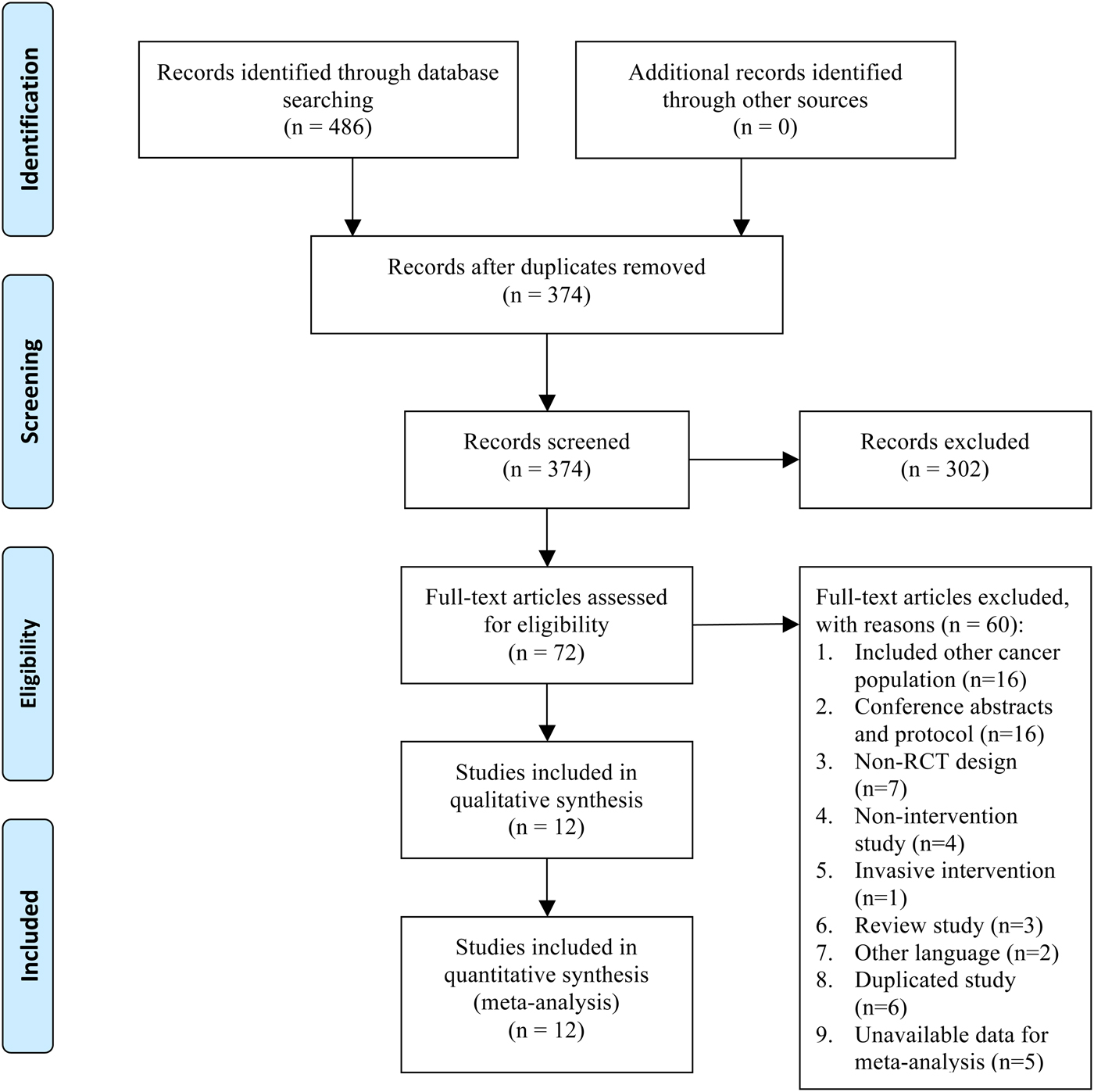

Figure 1 depicts a flowchart that describes how studies were included in the current review. We identified possibly eligible articles from the PubMed database (n = 36), the EMBASE database (n = 204), the Cochrane database (n = 196), and the CEPS database (n = 50). A total of 486 studies were found using the reported search terms, and 112 were excluded due to duplication, leaving 374 studies retrieved and assessed for inclusion. Of these, 302 studies were irrelevant to the research question and 60 did not meet the inclusion criteria. We finally identified 12 studies with available data for inclusion in our metaanalytic study.

Fig. 1. Summary of study selection and exclusion. From Moher et al. (Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff2009).

Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies. The 12 studies with an RCT design were published between 1999 and 2015. Seven studies (Badr et al., Reference Badr, Smith and Goldstein2015; Bredin et al., Reference Bredin, Corner and Krishnasamy1999; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Groff and Maciejewski2010; Molassiotis et al., Reference Molassiotis, Charalambous and Taylor2015b ; Morano et al., Reference Morano, Mesquita and Silva2014; Porter et al., Reference Porter, Keefe and Garst2011; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014) were conducted in Western countries (United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Brazil), and five (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Mu and He2006; H.M. Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tsai and Wu2015; Ni et al., Reference Ni, Zhang and Zheng2009; Wu & Wang, Reference Wu and Wang2003; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Li and Liu2012) were conducted in Chinese societies (China and Taiwan). In 50% of the included studies, subjects were recruited from multicenter hospitals. Most of the studies had a two-armed design (intervention vs. controls), whereas only one had a three-armed design (two interventions vs. controls) (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Groff and Maciejewski2010).

Table 1. Characteristics of studies for supportive care interventions

The mean age of our 1,472 participants was 59.16 years (range = 55.9–70.5 years). Most of the studies included patients with different stages of cancer and all types of lung cancer, though three studies included only patients diagnosed with NSCLC. Only one study screened for levels of depressive symptoms before the trial, and the inclusion criteria referred to depressive symptoms that met the criteria for major depressive disorder (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014).

Three types of supportive care interventions were identified: psychoeducation alone (Bredin et al., Reference Bredin, Corner and Krishnasamy1999; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Groff and Maciejewski2010; Ni et al., Reference Ni, Zhang and Zheng2009; Porter et al., Reference Porter, Keefe and Garst2011), psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation (Badr et al., Reference Badr, Smith and Goldstein2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Mu and He2006; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014; Wu & Wang, Reference Wu and Wang2003; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Li and Liu2012), and exercise programs (H.M. Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tsai and Wu2015; Molassiotis et al., Reference Molassiotis, Charalambous and Taylor2015b ; Morano et al., Reference Morano, Mesquita and Silva2014). Psychoeducation alone included three main components: information, skills training, and support (Bhattacharjee et al., Reference Bhattacharjee, Rai and Singh2011). The information phase provided knowledge about the disease and treatments. Skills training taught coping strategies with which to manage symptom distress. The support phase focused on discussions about their own feelings and available social support. For psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation program, the psychotherapy component was aimed at managing psychological problems and was developed based on specific theories of psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral and interpersonal). The exercise programs included inspiratory muscle training, whole-body aerobic exercise training (treadmill), and walking training.

The median duration of supportive care interventions was 10 weeks (range = 4–32 weeks). The number of sessions varied from 6 to 60, but four studies (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Groff and Maciejewski2010; Ni et al., Reference Ni, Zhang and Zheng2009; Wu & Wang, Reference Wu and Wang2003; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Li and Liu2012) did not report on how many sessions were provided. The majority of included studies (8 of 12) were delivered within a face-to-face format. More than two-thirds of the studies used standard care as a control condition. Depressive symptoms were evaluated by well-validated measures. We employed the cutoff point of the depression scales to determine level of clinical depression as per a patient's score: total scores of 8 on the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), 49 for the Self-Reported Depression Scale (SDS), 13 for the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and 9 for the Psychosocial Screen for Cancer, Depression Subscale (PSSCAN–D).

Risk of Bias

A weak rating was commonly related to performance bias. Due to the lack of details about participant recruitment and data collection procedures, unclear or high risks of sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding of outcome assessments were observed in 25, 41.67, and 33.3% of included studies, respectively. Moreover, 33.33% of included studies, those that did not conduct an intention-to-treat analysis, were defined as having a high risk of attrition bias.

Posttreatment Effects of Supportive Care Interventions on Depressive Symptoms

We first adopted a random-effects pooling model to examine the differences between the control and intervention groups at baseline. We found no significant differences in baseline conditions for all the studies (SMD = 0.05, CI 95% = –0.05 to 0.15, p = 0.32). The posttreatment effects are presented in Figure 2. A pooled SMD indicates that the overall effects of all supportive care interventions produced significantly greater reductions of depressive symptoms compared to controls (SMD = –0.74, CI 95% = –1.07 to –0.41, p < 0.0001). Considerable heterogeneity across these studies was also found (χ2 = 95.43, df = 11, p < 0.00001, I 2 = 88%).

Fig. 2. Posttreatment effects.

With respect to the effects of different types of supportive care interventions compared with controls, psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation (5 of 12 studies) demonstrated significant decreases in depressive symptom scores (SMD = –1.05, CI 95% = –1.25 to –0.85, p < 0.00001; χ2 = 4.63, df = 4, p = 0.33, I 2 = 14%). Greater reductions in depressive symptoms also occurred in participants receiving exercise interventions (3 of 12 studies) compared with members of control groups (SMD = –0.66, CI 95% = –1.02 to –0.30, p = 0.0003; χ2 = 2.58, df = 2, p = 0.28, I 2 = 22%). In contrast, psychoeducation alone (4 of 12 studies) did not yield significant reductions in depressive symptoms compared with controls (SMD = –0.39, CI 95% = –0.94 to 0.15, p = 0.16; χ2 = 35.59, df = 3, p < 0.00001, I 2 = 92%).

Follow-Up Effects of Supportive Care Interventions on Depressive Symptoms

The follow-up effects of supportive care interventions were examined in four studies with a long-term follow-up design. Figure 3 depicts the trend of follow-up effects. Two of the included studies (Molassiotis et al., Reference Molassiotis, Charalambous and Taylor2015b ; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014) provided follow-up data at the weeks 4 and 8 after the end of the intervention, involving 92 patients in the intervention arm and 97 patients controls. These results indicate that the effects were maintained at weeks 4 and 8 (pooled SMD = –0.78, CI 95% = –1.07 to –0.48, p < 0.0001; pooled SMD = –0.55, CI 95% = –0.84 to –0.26, p = 0.0002). Two studies (H.M. Chen et al., Reference Chen, Tsai and Wu2015; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014) that included 126 patients in the intervention arm and 132 controls reported a smaller but still significant effect on reduction in level of depression 12 weeks after the end of the intervention (pooled SMD = –0.48, CI 95% = –0.73 to –0.23, p = 0.0001). However, two studies (Porter et al., Reference Porter, Keefe and Garst2011; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014) with 185 participants in the intervention arm and 190 controls indicated that the interventions were not effective in improving depression at 16 weeks follow-up (SMD = –0.28, CI 95% = –0.70 to 0.14, p = 0.19).

Fig. 3. Trend of follow-up effects.

Subgroup Analysis

From Table 2 we can see that research methodology did not have a statistically significant impact on the results: study design (p = 0.49), cancer type (p = 0.52), cancer stage (p = 0.92), and intervention sessions (p = 0.36). However, we found that larger effect sizes and greater improvements in depressive symptoms occurred in lung cancer patients who had clinical depression at baseline (SMD = –7.93, CI 95% = –13.43 to –2.44), compared to those with scores below levels of clinical depression at baseline (SMD = –1.68, CI 95% = –3.39 to 0.02, p = 0.03). The larger effect sizes were in favor of psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation (SMD = –1.05, CI 95% = –1.25 to –0.85) and exercise programs (SMD = –0.66, CI 95% = –1.02 to –0.30) compared with psychoeducation alone (SMD = –0.39, CI 95% = –0.94 to 0.15, p = 0.03); 4–8 week duration of interventions (SMD = –1.04, CI 95% = –1.35 to –0.73) compared to 10 weeks (SMD = –0.37, CI 95% = –0.73 to –0.00, p = 0.006); and interventions provided through face-to-face delivery (SMD = –0.96, CI 95% = –1.25 to –0.68) compared with telephone delivery (SMD = –0.30, CI 95% = –0.65 to 0.06, p = 0.004).

Table 2. Subgroup analyses of supportive care interventions

*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

Sensitivity Analysis

To test the robustness of significant results, we conducted sensitivity analyses by comparing the results with and without dropping studies with small sample sizes (<50), with high or unclear risks of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessments, and incomplete outcomes data. As presented in Table 3, all effect sizes remained significant after dropping the above studies. The sensitivity analyses demonstrated that our overall results and conclusions were not changed by the methodological quality of included studies.

Table 3. Sensitivity analysis

DISCUSSION

Our metaanalysis of 12 RCT studies (1,472 participants) examined the overall effects of supportive care interventions on depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients. Our results indicate that the supportive care interventions can improve depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients (SMD = –0.74, CI 95% = –1.07 to –0.41). Three types of supportive care interventions were identified: psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation, psychoeducation alone, and exercise programs. We further examined the effects of different types of supportive care interventions and found that psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation and exercise programs effectively reduced depressive symptoms, whereas psychoeducation alone did not. Four studies with long-term follow-up showed that the interventions maintained significant effectiveness at weeks 4, 8, and 12 post-intervention.

Walker et al. (Reference Walker, Sawhney and Hansen2013) found that psychological interventions which included symptom management for breathlessness, screening for psychological distress, and psychosocial counseling seem to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients. Using the rigorous method of metaanalysis, our results indicate that, compared to standard care, psychoeducation alone does not offer significant improvement of depressive symptoms (SMD = –0.39, CI 95% = –0.94 to 0.15), but psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation produced significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms for lung cancer patients (SMD = –1.05, CI 95% = –1.25 to –0.85). Our results suggest that in lung cancer patients, who often experience a heavy symptom burden and have a poor prognosis, psychoeducation alone (which provides information, skills training for symptom management, and general support) could not effectively manage their depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that a better supportive care model for lung cancer patients would combine psychoeducation with psychotherapy. A previous metaanalysis (Akechi et al., Reference Akechi, Okuyama and Onishi2008) reported the positive effects of psychotherapy on depressive symptoms in patients with different types of cancer (SMD = –0.44, CI 95% = –0.08 to –0.80). In our metaanalysis, psychotherapy alone was not provided to lung cancer patients but was always combined with psychoeducation in the review articles. Psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation can target the causes of depressive symptoms (e.g., symptom distress) and psychological problems (e.g., grief from loss of control) (Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Papadopoulou and Kotronoulas2013). This combined supportive care program demonstrated that psychotherapy can also manage the impact of psychological problems on physical symptom distress. Another previous study proposed a model of interdisciplinary palliative care for lung cancer patients that emphasizes the use of professionals to manage the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs of lung cancer patients (Ferrell et al., Reference Ferrell, Koczywas and Grannis2011). Our findings suggest that integrating psychotherapy with symptom management in lung cancer patients can effectively manage the mutual influences between physical symptoms and psychological problems. For example, nurses can provide cognitive behavioral therapy to manage the impact of negative thoughts on breathlessness (e.g., “I cannot get enough air; my cancer must be getting worse”) and offer education on diaphragmatic breathing and relaxation techniques (Greer et al., Reference Greer, MacDonald and Vaughn2015). Psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation can effectively improve depressive symptoms by managing thoughts of “disaster” and their impact on such symptoms as dyspnea for patients with advanced lung cancer.

Another previous metaanalysis (Craft et al., Reference Craft, Vaniterson and Helenowski2012) indicated that exercise effectively improves depressive symptoms in cancer survivors (mainly breast cancer survivors; expected shortfall = –0.22, CI 95% = −0.43 to –0.09, p = 0.04). Our metaanalytic study consistently found that exercise programs (e.g., pulmonary rehabilitation, home-based exercise, and inspiratory muscle training) contributes to greater reductions in depressive symptoms for lung cancer patients (SMD = –0.66, CI 95% = –1.02 to –0.30). Exercise programs can target such physical factors of depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients as postoperative complications, dyspnea and respiratory problems, fatigue, and insomnia, especially those with additional chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Bade et al., Reference Bade, Thomas and Scott2015; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Liao and Shun2011; Maneeton et al., Reference Maneeton, Maneeton and Reungyos2014; Vijayvergia et al., Reference Vijayvergia, Shah and Denlinger2015). Moreover, exercise programs can produce such positive physical effects as release of endorphins and normalization of cortisol levels and such psychological effects as positive thinking (Ranjbar et al., Reference Ranjbar, Memari and Hafizi2015).

The results with respect to moderator effects indicate greater effects of interventions on depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients who have severe levels of depressive symptoms at baseline. The lack of a significant effect on clinical depression scores might be related to a floor effect in this patient group. Moreover, the results of our study also suggest that interventions with durations of 4–8 weeks contribute to greater improvement of depressive symptoms compared to interventions that last for more than 10 weeks. Our results suggest that interventions that last more than 10 weeks might translate into added burden for lung cancer patients.

Our metaanalytic study revealed that significant improvements were achieved with the face-to-face delivery format, while there were no significant effects with interventions conducted via telephone. It is noteworthy that none of the included studies examined the impact of interventions provided in a group format. The stigma attached to smoking behaviors results in a sense of shame for patients, and social rejection is associated with depressive symptoms in lung cancer patients (Dirkse et al., Reference Dirkse, Lamont and Li2014; Gonzalez & Jacobsen, Reference Gonzalez and Jacobsen2012). Interventions in a group format might be helpful in reducing depressive symptoms, as lung cancer patients could share their psychological burdens caused by the social stigma and obtain peer support (Lehto, Reference Lehto2014). A previous metaanalysis (Faller et al., Reference Faller, Schuler and Richard2013) found that group psychotherapy has a larger effect (d = 0.21–0.48) on depressive symptoms than individual psychotherapy (d = 0.13–0.35) in cancer patients. Accordingly, future studies need to develop and examine the effect of group-format supportive care interventions on depressive symptoms in the lung cancer patient population.

Due to several methodological limitations, our findings need to be interpreted with caution. First, we only reviewed studies published in English and Chinese. Due to a lack of available data, five studies were excluded from our metaanalysis. Second, the heterogeneity of some moderator effects remained high. Finally, the existence of a publication bias cannot be ignored. It should be noted that publication bias has some effect on the available evidence pool.

CONCLUSIONS

Our metaanalytic study (with some 1,472 participants) found that psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation and psychotherapy combined or with an exercise program are the most effective types of supportive care interventions, while psychoeducation alone does not yield significant improvements. The guidelines for management of depression in patients with cancer (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, DeRubeis and Berman2014) suggest that personalized supportive care can be provided based on different levels of symptoms, functional impairment, and patient preference. According to our results, personalized supportive care interventions can be provided based on the main causes of depressive symptoms as well. An exercise program can be applied for lung cancer patients with impaired respiratory function, as this is one of the main causes of their depressive symptoms. We find that psychotherapy combined with psychoeducation can be applied to manage physical symptom distress and psychological problems, two of the main causes of depression in lung cancer patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The abstract of the present study was presented as a poster at the 2017 ICCNCC meeting in Rome. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Hsien-Ho Lin for his help with statistical calculations.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors hereby declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Our research was not supported by any specific grant from a public funding agency, nor any funding from the commercial or not-for-profit sectors.