INTRODUCTION

Addressing a patient's spiritual concerns is considered a critical component of holistic patient care, leading many to expand George Engel's biopsychosocial model to a more encompassing biopsychosociospiritual model (Engel, Reference Engel1977; Katerndahl & Oyiriaru, Reference Katerndahl and Oyiriaru2007; Puchalski et al., Reference Puchalski, Ferrell and Virani2009). Addressing patients' spirituality is particularly salient in the intensive care unit (ICU), as studies have found that patients who have more severe illnesses are more likely to say that spirituality is important to them (Wagner & Higdon, Reference Wagner and Higdon1996; MacLean et al., Reference MacLean, Susi and Phifer2003; McCord et al., Reference McCord, Gilchrist and Grossman2004). Additionally, other studies have found that patients' and families' spiritual concerns can drive their end-of-life care decisions (Shinall et al., Reference Shinall, Ehrenfeld and Guillamondegui2014). Hospital chaplains are professionally trained to attend to patients' spiritual concerns.

Throughout the last few decades, the role of the hospital chaplain has been debated (VandeCreek & Burton, Reference VandeCreek and Burton2001; Loewy & Loewy, Reference Loewy and Loewy2007; Thorstenson, Reference Thorstenson2012; Hunt & Cobb, Reference Hunt and Cobb2003). Some have argued for more evidence-based practices in chaplaincy (Ruff, Reference Ruff1996; O'Connor, Reference O'Connor2002; Jensen, Reference Jensen2002; Hunt & Cobb, Reference Hunt and Cobb2003). This has led in part to calls for chaplains to document their encounters with patients in the medical record, so that the spiritual assessment and plan are available to other health practitioners. The Association of Professional Chaplains (2009) made clinical documentation a standard of practice in the acute care setting. How chaplains document their encounters, however, varies widely, even within institutions, from marking a checklist of interventions to writing a detailed narrative of the encounter (Ruff, Reference Ruff1996; Rosell, Reference Rosell2006; Carey & Cohen, Reference Carey and Cohen2015).

Many leaders within the profession of medicine have affirmed the importance of addressing patients' spiritual concerns, particularly in an ICU (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Engelberg and Nielsen2014; Puchalski, Reference Puchalski2001). Little has been known, however, about the forms that documentation takes in different settings and about how clinicians interpret chaplain documentation. To begin to fill in this gap in the literature, the present study examines the clinical notes of chaplains working in the ICUs of one major academic medical center. A research team of two practicing physicians (PC and FC) and one medical student (BL) used qualitative analysis to describe patterns in how chaplains document their encounters with patients and their families in the ICU. By offering the perspectives of clinician users of the medical record, we hope this study will help to inform the chaplain community as it continues to refine its practices of documenting its work in the medical record.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was part of a larger project in which we performed a retrospective chart review of all of the chaplain notes filed on patients in the adult intensive care units (medial, surgical, cardiac, cardiothoracic, and neurological) at Duke University Hospital between June 24 and December 24, 2013 (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Curlin and Cox2015).

Electronic Medical Record Format

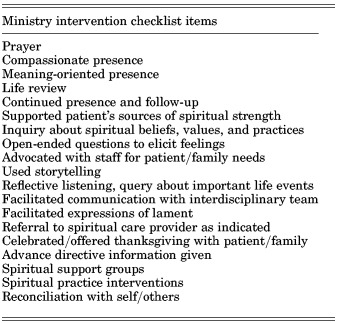

At Duke University Hospital, the electronic medical record (EMR) template for chaplain entries consists of two sections. The first is what can be referred to as the “close-ended” section. It is completed using checkboxes and pull-down menus. It includes basic items, such as who requested the visit and with whom the chaplain discussed the visit. One item in this section is a checklist of “ministry interventions” (Table 1). These interventions include such phrases as “meaning-oriented presence,” “facilitated expressions of lament,” and “use of storytelling.” In addition to the close-ended portion, the EMR template also includes an optional free-text section. We focused on this free-text section in our study.

Table 1. “Ministry Intervention” checklist in close-ended portion of EMR template for chaplain entries at Duke University Hospital

We met with the director of pastoral services at the hospital to review procedures in chaplain documentation. At Duke, only yearlong chaplain residents and certified chaplains—those who see patients in an ICU—are permitted to document free text in the EMR. They are not instructed to use any particular format or template for such free text.

Data Analysis

First, two investigators (BL and PC) independently read and analyzed 30 of the text excerpts, highlighting words and phrases to identify relevant concepts used in the notes and to take note of the themes that emerged from chaplain documentation. They then met together to develop a consensus through a working codebook of categories, subcategories, and themes. At that point, a third investigator (FC) read and coded the same 30 excerpts and met with BL and PC to modify and amplify the codebook. Using qualitative analysis software (NVivo, QSR International, Melbourne, Australia), BL then independently coded all 255 of the text excerpts according to the codebook. When new concepts emerged, they were added to the schema. PC reviewed all of the excerpts with BL's coding in view, and the two then met to discuss and resolve any differences in coding. In this iterative process, the investigators identified emergent themes, as well as the relationships between these themes. At this point, FC systematically reviewed the text excerpts and the interpretations for consistency and proposed alternative interpretations where relevant. When consensus was reached, we chose representative quotations to demonstrate the themes we had identified. Finally, after drafting the manuscript, we read the text excerpts again to be sure that the manuscript faithfully expressed the emergent themes.

We employed credibility checks common to qualitative research techniques. Using reflexivity, the “illusion of denying the human touch is countered by establishing an agenda for assessment of subjectivity” (Malterud, Reference Malterud2001). This includes declaring beliefs before the start of the study and looking at the data for competing conclusions. To use reflexivity in the present study, prior to analysis of the text, the investigators met to discuss and make explicit note of the personal dimensions that each brought to the research table and how to mitigate against preconceived biases or premature conclusions. In particular, we consciously foregrounded the fact that we came to this study as clinicians, which both limits our understanding of what chaplains are doing but also provides an important untutored perspective from clinician users of the medical record in which chaplains are documenting. To employ triangulation, another important credibility check in qualitative research, we involved multiple perspectives in an iterative process of coding, analysis, and interpretation.

RESULTS

During the study period, 4169 patients were admitted to the adult ICUs, 248 (6%) of whom were visited by chaplains. The demographic characteristics of patients seen by chaplains are displayed in Table 2. Chaplains wrote 255 free-text excerpts describing encounters with 152 unique patients, with 1 to 8 free-text entries per patient; 109 of these patients had at least one follow-up visit with a free-text entry.

Table 2. Demographics of patients with documented chaplain care

a Included in the number of Protestant patients were 65 Baptists, who represented 26% of the total patient population in our study.

Four primary themes emerged from chaplain documentation.

Frequent Use of “Code Language”

Chaplain notes frequently included what we call “code language”—a recurrent word or brief phrase seeming to mark a larger concept or activity understood in common. Recurrent phrases also often served as the introduction to the notes. For example, notes commonly began with “provided support for family and patient” or “chaplain visited patient.”

Code language used by chaplains was seen throughout the text of the notes, sometimes including phrases repeated verbatim from the checklist of ministry interventions. For example, the phrases “chaplain provided compassionate presence” and “chaplain facilitated opportunities for lament”—both items on the ministry intervention checklist—were often included in notes. Other code language, although not included in the ministry intervention checklist, was similarly seen across notes. For example, many notes included the phrase “chaplain inquired about patient's well-being.” Altogether, much of this code language, in different terms, documented that the chaplain was there.

Description Rather than Interpretation

Much of the text could be characterized as describing what the chaplain observed rather than interpreting the clinical significance of what was observed during the encounter. For example, a chaplain wrote, “Family is quite large,” one of many examples in which the chaplain described some aspect of the setting without interpreting its significance for the patient's experience or their care. In another example, a chaplain wrote, “Parents indicated that they are just waiting. Pt's mother was standing next to daughter holding her hand, and pt's father was sitting next to the pt holding her hand and stroking her forehead.” Again, the chaplain described what was happening in the patient's room without interpreting its clinical significance or without documenting an assessment of the patient's spiritual needs or resources.

Similarly, chaplain notes sometimes recapitulated clinical information that was almost certainly documented elsewhere in the patient's chart. For instance, one chaplain wrote, “Pt has lung cancer and had been in hospice.” Another wrote, “Pt's husband explained the pt's past nine months of heart troubles, including atrial flutter and a-fib. Pt is due for an ablation on 10/15.”

Interestingly, chaplains also described patients' spiritual and religious characteristics, as well as patients' wishes regarding end-of-life care, without interpreting the significance of this information. Religious beliefs were typically documented by citing the patient's or family's specific religious tradition, such as “patient's mother identifies as ‘Baptist’” or “pt is ‘Presbyterian.’” Chaplains typically conveyed end-of-life preferences by directly quoting a family member. For instance, a chaplain quoted a patient's daughter thus: “I just don't want her to suffer,” and “She wouldn't want to be on life support, so I don't know what I am gonna do.”

Although less common, chaplains did sometimes interpret what was observed or provide an assessment. One wrote, “I believe the family is aware of the seriousness of their mother's situation.” Another wrote, “The wife was visibly upset, but wanted to focus on making her husband's goal happen.” The following chaplain note stood out both for its level of detail and its depth of clinical interpretation:

Chaplain visited with Patients 3 adult children. All 3 have a strong faith but are also in somewhat different places regarding their mothers prognosis. All 3 do not want their mother to suffer, but one is still trying to discern if accepting her mothers death is denying her faith in God. Patients son believes God's will is perfect, and that although he wants a miracle, he trusts that God's will is perfect and will be done. The 3rd, a daughter, is at peace with the possibility of her mothers death, but is concerned about what to say to her own 4 children. Chaplain listened to each person, and prayed with the family for peace, wisdom, strength, and for their mother that God's will is done, and in God's will, whatever that might be, the family will find peace.

In each of these cases, the chaplain draws a conclusion based on his or her interaction with the patient's family, rather than merely describing the details of that interaction.

Passive Follow-Up Plans

When chaplains indicated a plan for follow-up in their notes, that plan was most often passive, indicating that the family or clinical team could contact the chaplain for follow-up if desired. Some examples: “Informed family of availability of hospital chaplains,” “Please page as needed,” and “Encouraged family to contact chaplain if any needs arise.” Rarely did a note indicate a specific plan for the chaplain to follow up on his or her own.

Additionally, when chaplains wrote more than one note on the same patient, their subsequent notes rarely referred to observations made in their previous notes; 109 patients had free-text entries during one or more follow-up visits from chaplains, but in only two cases did such entries refer to any observations from a prior chaplain visit.

Insight into Relationship Dynamics

Some chaplain notes provided insights into particular relationship dynamics. These might be family dynamics, as one chaplain reported: “There seems to be family tension between the patient's fiancée and his 2 sons.” These might also be dynamics between the patient—or the patient's family—and the medical team. One chaplain conveyed the frustration of a patient's wife, writing that the wife expressed “feeling ‘angry’ with the care provided by a previous hospital” and that she was “afraid that they ‘missed the window of opportunity’ to care for her husband's illness.” Another note read, “Chaplain explored patient's cousin's spiritual beliefs and assured patient's cousin that she has the freedom to share her perspective even when it may seemingly conflict with the perspective of the medical team.” Similarly, one chaplain wrote:

Pt's wife […] explained frustration that it took so long for the pt to receive the trach. Pt's wife admitted that she got upset and felt remorseful for her anger. Chaplain made space for pt's wife to express her frustration and reminded pt's wife that it is okay to be an advocate for her husband's care.

In the latter two examples, it seems that the chaplain takes on the role of an advocate for a member of the patient's family when that member's perspective conflicts with that of the medical team.

LIMITATIONS

Qualitative methods provide a powerful tool for gaining a broader understanding of “clinical realities” (Malterud, Reference Malterud2001). As with most qualitative studies, our study sample was guided by the study question and was not intended to be statistically representative nor to be used to make inferences regarding how the themes we found are distributed across the broader universe of chaplain notes. We analyzed chaplains' notes from a six-month time period in particular intensive care units at one academic medical center in the Southeastern United States. The study time period coincided with the institution of a new EMR at this medical center, which may have affected what chaplains included in their notes. During this time, chaplains visited 6% of all the patients admitted to the included ICUs. While this percentage is low, Duke is a very large academic medical center with a limited chaplain staff and therefore relies heavily on chaplains in training.

As noted, the study investigators are physicians (one in training), thereby creating a particular interpretive lens. Documentation in the medical record serves as a means of communication between and among members of the medical care team. Our study focused on how clinicians perceive chaplain notes. It is possible that the themes we found differ at least somewhat from those that would be found by investigators with different clinical expertise, such as chaplains, nurses, and social workers. Future studies involving such perspectives are warranted to see to what extent our findings describe chaplain documentation in the ICUs of other medical centers and in other clinical contexts.

DISCUSSION

Chaplains are the health professionals with the most training to attend to the spiritual dimensions of patients' experiences. They have more time and expertise for drawing out information, interpreting its significance, and responding to patients' spiritual concerns. Indeed, with respect to spiritual care, some have suggested that healthcare practitioners are the generalists and chaplains the specialists (Puchalski et al., Reference Puchalski, Ferrell and Virani2009).

The unique contributions of chaplains to patients' care, however, are not always visible to clinicians and hospital administrators. Several investigators have studied the effects of spiritual care on patients' and their families' experiences in the hospital, although these studies did not distinguish spiritual care provided by chaplains from that provided by other health practitioners (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Meltzer and Arora2011; Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Thomas and VandeCreek1991; Astrow et al., Reference Astrow, Wexler and Texeira2007). Specific to the ICU, one study found that patients with more activities performed for them by spiritual care providers had greater family member satisfaction (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Engelberg and Nielsen2014). However, after a recent review, Jankowski, Handzo, and Flannelly concluded that “more and better studies are needed to test the efficacy of chaplaincy interventions,” specifically to determine the “best chaplaincy practices to optimize patient and family health outcomes” (Jankowski et al., Reference Jankowski, Handzo and Flannelly2011),

Clinical documentation by chaplains could make what they do and the benefits they provide more visible to clinicians and hospital administrators (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Berlinger and Cadge2008). Ruff (Reference Ruff1996) argued that charting helps chaplains to assert the importance of their profession and their role in the care of hospitalized patients. Jensen (Reference Jensen2002) noted that documentation provides data for research that can validate the work of chaplains (Ruff, Reference Ruff1996). Moreover, as clinicians, we note that the clinical record provides at least the opportunity for communication with the interdisciplinary team. This can be especially useful in a busy setting, where it may be difficult for a chaplain to have a face-to-face discussion with a nurse, physician, or other care team member.

In the present study, however, we found that chaplains in the ICU devoted most of their notes to documenting information that is already readily available to the clinical team. Such documentation seems unlikely to facilitate conversation with clinicians regarding patients' spiritual experiences. Likewise, chaplains seldom incorporated in their notes what might be interpreted as spiritual assessments, such as a patient's spiritual needs or resources. Moreover, we rarely saw spiritual plans or expected outcomes documented in chaplains' notes, nor did subsequent notes refer to observations in previous notes. This contrasts with the typical pattern of clinician documentation (setting aside documentation that is driven by billing concerns), in which clinicians document what they or other members of the clinical team need to know to guide subsequent clinical care.

In a related vein, the code language we observed in chaplain notes does not seem to convey the deeper spiritual connection that chaplains often have with patients and theirs families in the ICU. In 2006, chaplain Tarris Rosell wrote about his experience with the commercial nomenclature required for documentation at a VA hospital (Rosell, Reference Rosell2006). As a result of that language, he wrote, chaplains' interactions with patients were viewed as “products for delivery.” Similarly, it seems that the ministry intervention checklist at the institution in that study encourages the use of code language that conveys the work of chaplains as so many product units of “compassionate presence” and other ambiguous terms.

Another concern shaping chaplains' documentation may be patient confidentiality. Wendy Cadge, a researcher who studied chaplaincy departments at major academic institutions, saw many institutions that supported “double documentation” (Cadge, Reference Cadge2009), wherein chaplaincy departments use their own charting systems that are not accessible to interdisciplinary teams. Ruff (Reference Ruff1996) argued that, although chaplains should respect patients' confidentiality, documentation helps to keep the clinical team informed and provides information not found elsewhere in the chart. Loewy and Loewy (Reference Loewy and Loewy2007), however, in their oft-quoted article “Healthcare and the Hospital Chaplain,” argued that chaplains should not have access to the medical record, because they are not, and should not be, members of the healthcare team. This debate surrounding confidentiality and chaplain documentation was tied to parallel debates regarding the role that chaplains should play in patient care teams.

Despite debate over the past decades, evidence suggests that chaplains are in fact now widely regarded as members of the patient care team. A study of the top-ranked hospitals in the United States in 2011 showed that all 34 granted their chaplains access to the medical record, and all but one allowed chaplains to write notes (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Marin and Umpierre2011). A consensus conference on spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care emphasized that “documentation is essential to communicate spiritual concerns” with the interdisciplinary team (Puchalski et al., Reference Puchalski, Ferrell and Virani2009). In the case of palliative care patients, George Handzo (Reference Handzo2011) has emphasized that the plan documented by the chaplain should include expected outcomes, as well as interventions for all members of the healthcare team. Peery (Reference Peery and Roberts2012) has advocated for a standardized chaplaincy charting model, with documentation of the reason for the chaplain visit, interventions, outcomes, an assessment, and a plan.

Having chaplains document in the medical record is consistent with the goals of the clinical pastoral education (CPE) program at the medical center in our present study. The program trains chaplain residents based on standards outlined by the Association for Clinical Pastoral Education (2015). Chaplain residents are expected to understand their professional role and know how to work effectively as a member of a multidisciplinary team, including “clear, accurate professional communication” that documents “one's contribution of care effectively in the appropriate records.” Despite this standard, chaplains in different contexts will of course have had different training experiences and will deploy different practices of documenting their work. Although the association is not a chaplain-certifying body, CPE trainees provide much of the clinical pastoral care, in concert with a limited number of staff chaplains. As such, our study highlights the need for standardization of documentation not only among chaplains but also among those providing spiritual care via CPE training.

Insofar as chaplains are considered a member of the healthcare team and insofar as they are documenting their work in the medical record, it seems to us that this documentation should provide clinically relevant communication. Such communication was rarely found in the present study. Studies of patient and family satisfaction make clear that addressing spiritual concerns is important and that chaplains are valued members of the clinical team—particularly for patients with advanced or critical illness (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Engelberg and Nielsen2014; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Meltzer and Arora2011; Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Thomas and VandeCreek1991; Astrow et al., Reference Astrow, Wexler and Texeira2007). The value that chaplains contribute, however, through the depth of their interactions with patients, does not seem to be conveyed in the pattern of clinical documentation we observed. We hope that our study stirs further consideration of how chaplain documentation can enhance patient care and convey the unique value that chaplains can add to the clinical team.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jim Rawlings, Director of Pastoral Services, for his input.

DISCLOSURES

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.