Background

Delirium as a neuropsychiatric syndrome is characterized by its abrupt onset and fluctuating course, disturbances in consciousness and cognition, as well as noncognitive domains such as motor behavior, emotionality and sleep–wake cycle, and an underlying etiology (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Breitbart and Franklin1999; American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Delirium has been recognized to be the most common neuropsychiatric syndrome across the healthcare setting (Bucht et al., Reference Bucht, Gustafson and Sandberg1999; Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Westendorp and Saczynski2014). For instance, cardiac surgery procedures can cause delirium in up to 70% of patients (Norkiene et al., Reference Norkiene, Ringaitiene and Misiuriene2007; Gottesman et al., Reference Gottesman, Grega and Bailey2010). Further, in the intensive care setting, in mechanically ventilated patients, delirium reaches rates of 80% (Pun and Ely, Reference Pun and Ely2007). In addition, delirium inflicts short-term (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Clagett and Valentine2002; Santos et al., Reference Santos, Velasco and Fraguas2004) and long-term adversities for both patients and the health care system (Koster et al., Reference Koster, Hensens and van der2009). These adversities include a prolonged length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) (Ely et al., Reference Ely, Shintani and Truman2004; Ouimet et al., Reference Ouimet, Kavanagh and Gottfried2007), more frequent or prolonged mechanical ventilation (Heymann et al., Reference Heymann, Radtke and Schiemann2010), as well as increases in morbidity and mortality rates (Balas et al., Reference Balas, Happ and Yang2009; Heymann et al., Reference Heymann, Radtke and Schiemann2010). As a long-term consequence, a decline in functionality and cognitive abilities (Bickel et al., Reference Bickel, Gradinger and Kochs2008), as well as increased rates of institutionalization have been recognized (Ouimet et al., Reference Ouimet, Kavanagh and Gottfried2007).

Several instruments have been developed to improve the screening and diagnosis of delirium. Across all hospital settings, one of the most commonly used instruments is the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-1998 (DRS-R-98) (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Mittal and Torres2001). The total score — consisting of the severity and diagnostic set — distinguishes delirium from dementia, schizophrenia, depression, and other medical illnesses during blind rating, with sensitivity ranging from 91 to 100%, depending on the cut-off score chosen (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Mittal and Torres2001). The original English version has high sensitivity and specificity, inter-rater reliability, and concurrent validity to its predecessor, the DRS (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Baker and Greenhouse1988).

This instrument, however, has been rarely used in the intensive care setting, although providing a very detailed characterization of delirium. One study focusing on the incidence, prevalence, risk factors, and outcome of delirium documented an incidence and prevalence of 24.4 and 53.6%, respectively. The mean DRS-R-98 diagnostic score was 11.3, and the total score is 16.2. No further details about the individual DRS-R-98 items were provided (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Malhotra and Grover2012; Lahariya et al., Reference Lahariya, Grover and Bagga2016). Another study provided more detailed DRS-R-98 information, and commonly documented symptoms of delirium were sleep–wake cycle disturbances, lability of affect, thought abnormalities, inattention and disorientation, as well as short- and long-term memory impairment. Delusions were rarely recorded (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Malhotra and Grover2012; Lahariya et al., Reference Lahariya, Grover and Bagga2016).

Sedation is one of the core concepts in the intensive care setting. The Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) (Sessler et al., Reference Sessler, Gosnell and Grap2002) has been developed to assess the level of sedation, alertness, and agitation on the ICU and is commonly used to achieve the appropriate level of sedation, avoiding under- or over-sedation. Obtaining the RASS score is the first step in the algorithm for assessing delirium with the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) (Ely et al., Reference Ely, Inouye and Bernard2001). Only one study assessed delirium dependent on RASS sedation and showed that drowsiness increased the odds for delirium eigthfold and was subthreshold for delirium (Boettger et al., Reference Boettger, Nunez and Meyer2017a).

To date, there are only few studies describing delirium in the intensive care setting with the DRS-R-98 and no studies assessing delirium dependent on the level of alertness, although with this knowledge, the understanding and identification of key features of delirium could be improved. Thus, in this study, the phenomenological characteristics of delirium in patients at RASS levels representing drowsy or alert and calm states were evaluated.

Methods

Patients

All patients in this prospective, descriptive cohort study were recruited on a 12-bed cardiovascular-surgical intensive care unit between May 2013 and April 2015 at the University Hospital Zurich with 39,000 admissions yearly. Inclusion criteria were being an adult, able to consent and intensive care management for more than 18 h. Exclusion criteria were the inability to consent or a history of substance use disorder and delirium caused by substance withdrawal.

This study was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Canton Zurich, Switzerland (PB_2016-01264).

Procedures

All patients in this study were informed about the rationale and procedures of this study and an initial attempt to obtain written informed consent was made. In those patients unable to provide written consent at that time, either due to more severe delirium, frailty, sedation, or lack of strength, proxy assent from the next of kin or a responsible caregiver was obtained instead. After medical stabilization, consent was obtained. If patients refused participation and consent, they were excluded.

The assessment of delirium was performed by four raters specifically trained in the use of the DRS-R-98 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 4th edition text revision (DSM-IV-TR), and inter-rater reliability was achieved for the latter.

The baseline assessment included several steps. At first, the patient was interviewed, second, the presence or absence of delirium was determined according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria, and third, the DRS-R-98 was completed.

If required, the assessment was completed by obtaining collateral information documented in the electronic medical record system (Klinikinformationssystem, KISIM, CisTec AG, Zurich) and family or caregivers.

Measurements

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-IV-TR

The diagnosis of delirium was determined by DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) including four criteria: A — disturbance of consciousness (i.e., reduced clarity of awareness of the environment) with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention; B — a change in cognition (such as memory deficit, disorientation, and language disturbance) or the development of a perceptual disturbance that is not better accounted for by a pre-existing, established, or evolving dementia; C — the disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to days) and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day; and D — there is evidence from the history, physical examination, and laboratory findings that (i) the disturbance is caused by the direct physiological consequences of a general medical condition, (ii) the symptoms in criterion (i) developed during substance intoxication, or during or shortly after, a withdrawal syndrome, or (iii) the delirium has more than one etiology.

Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale

The RASS is a medical scale developed to measure the level of sedation, alertness, and agitation (Sessler et al., Reference Sessler, Gosnell and Grap2002). This scale can be used in all hospitalized patients; however, it is mostly used in ventilated patients in order to avoid over- and under-sedation. The RASS includes ten points ranging from −5 to 4 and provides a detailed description for each score. The score of 0 represents the alert and calm patient, spontaneously paying attention to the caregiver. Negative scores describe the level of sedation, with −1 representing drowsiness, characterized by not being fully alert, sustained awakening as defined by more than 10 s, with eye contact to voice. Levels of −2 to −5 describe light, moderate, and deep sedation, as well as being unarousable. Positive scores describe the level of agitation, ranging from +1 to +4, representing restlessness, agitation, pronounced agitation, and combativeness (Sessler et al., Reference Sessler, Gosnell and Grap2002).

Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98

The DRS-R-98 is a 16-item scale with 13 items describing the severity, in addition to three diagnostic items, with four points — absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe impairment (Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz, Mittal and Torres2001). The rating of severity is clearly specified in the description of the scale. The diagnosis of delirium requires scores of more than 15 points on the severity scale or 18 points on the severity and diagnostic scale. The severity and diagnostic items are listed in Tables 2–4.

Motor activity is rated with items 7 — increased and 8 — decreased motor behaviors. The hyperactive subtype requires a score of 1 and more on item 7, increased motor behavior, in the absence of hypoactivity, the hypoactive subtype a score of 1 and more than on item 8, decreased motor behavior, in the absence of hyperactivity, the mixed subtype both hypo- and hyperactivity, and last, the no-motor-subtype the absence of hyper- or hypoactivity as evidenced by the corresponding items. The rating applies to the preceding 24 h.

Statistical methods

All statistical procedures were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Descriptive statistics were implemented for the characterization of the sample, such as sociodemographic, clinical variables, and delirium variables, in particular, the DRS-R-98 items and total scores. In a first step, the excluded patients were compared with those that were included, and in a second step, after dichotomizing the dataset into those with RASS score of 1 and 0, those patients with and without delirium were compared. Variables on the interval scale — such as age or laboratory parameters — were tested for normal distribution with Shapiro–Wilk's test, and the majority was found to be nonparametric. Further, parameters on ordinal scales — such as the severity of individual items on the DRS-R-98 — were present. In both instances, Mann–Whitney's U-tests were computed. For items on categorical scales, such as the gender distribution or presence of DRS-R-98 items, Pearson's χ 2 tests were performed.

The inter-rater reliability was determined by its corresponding Fleiss κ with agreement defined as >0.80 perfect (Landis and Koch, Reference Landis and Koch1977).

Following, a discriminate analysis to establish the ability of the DRS-R-98 items to correctly classify the presence versus the absence of delirium in those patients with RASS scores of −1 and 0 was computed with the function coefficient set on unstandardized. In addition, in order to further describe the ability of the DRS-R-98 to distinguish between delirium and the absence of delirium, the sensitivities and specificities, as well as corresponding positive and negative predictive values (PPVs and NPVs) were calculated and their confidence intervals determined as exact Clopper–Pearson confidence intervals.

For all implemented tests, the significance level alpha was set at 0.05.

Results

Inter-rater reliability with respect to DSM-IV-TR diagnosis

With respect to the DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of delirium, the overall rating agreement between the psychiatrists’ assessment was almost perfect (Cohen's Κ 0.89, CI 0.69–1.1, P < 0.001) and with respect to the presence and absence of delirium perfect (Cohen's Κ 0.97, CI 0.69–1.1, P < 0.001 and Cohen's Κ 0.93, CI 0.69–1.1, P < 0.001).

Characteristics of excluded patients versus those included

In total, 255 patients with corresponding RASS scores were identified, out of these 30 patients had RASS scores of ≥1 (n = 19) or <−1 (n = 11) and were excluded for the purpose of the study (Table 1). These patients were not different with respect to age, gender, length of stay on ICU and in hospital, discharge destinations, type of surgery, requirement for mechanical ventilation, or sedation at assessment. However, the excluded patients were assessed at a later day and were more often delirious. Among medical variables, the cardiac ejection fraction was lower and the dose of midazolam administered in the 24 h prior to assessment was higher.

Table 1. Sociodemographic, medical, and management characteristics of included versus excluded patients

Bold values are statistically significant, <0.05.

RASS, Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition, text revision; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Mann–Whitney's U-test.

b Pearson's χ 2 test.

* Mean, SD (standard deviation)/median, IQR (interquartile range).

Delirium in the presence of drowsiness (RASS = −1)

Description of the delirious versus the nondelirious sample

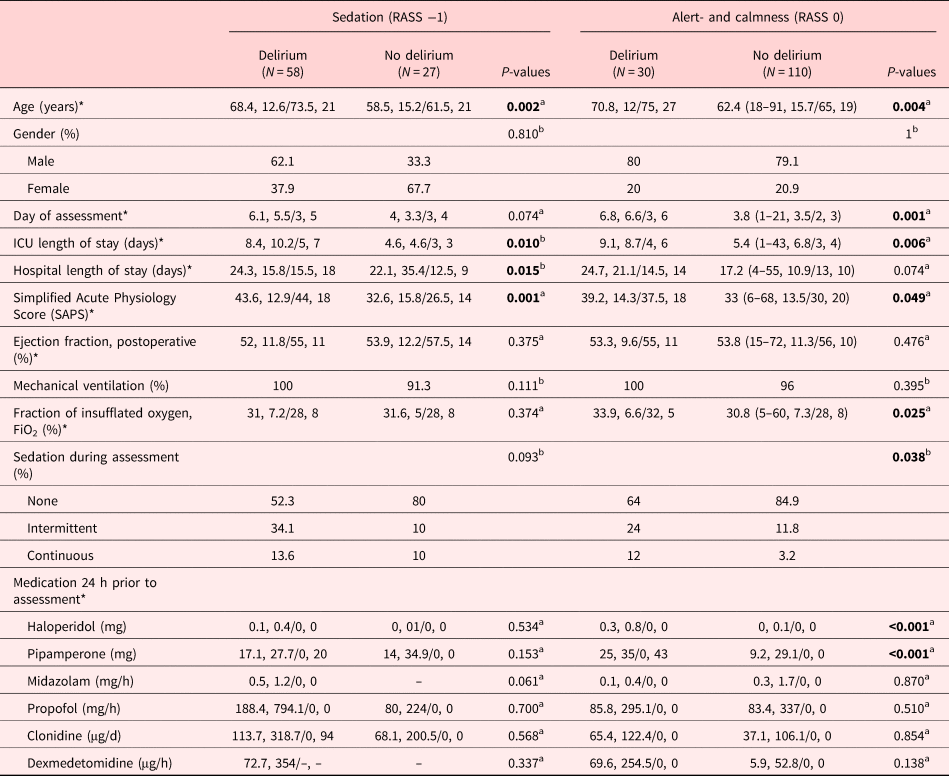

The sociodemographic and medical variables of those with the DSM-IV-TR defined the diagnosis of delirium versus those without are listed in Table 2. Patients with delirium were older, their disease was more severe as evidenced by the Simplified Acute Physiology Scores (SAPSs), and they had a prolonged stay on the ICU.

Table 2. Sociodemographic, medical, and management characteristics of delirium dependent on the RASS score −1 and 0

Bold values are statistically significant, <0.05.

RASS, Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition, text revision; ICU, intensive care unit;

a Mann–Whitney's U-test (MWU).

b Pearson's χ 2 test.

* Mean, SD (standard deviation)/median, IQR (interquartile range).

Conversely, the gender distribution, day of assessment and sedation of assessment, their ICU-discharge destination, hospital length of stay and discharge destination, type of surgery, rate of mechanical ventilation, or medications administered were not different.

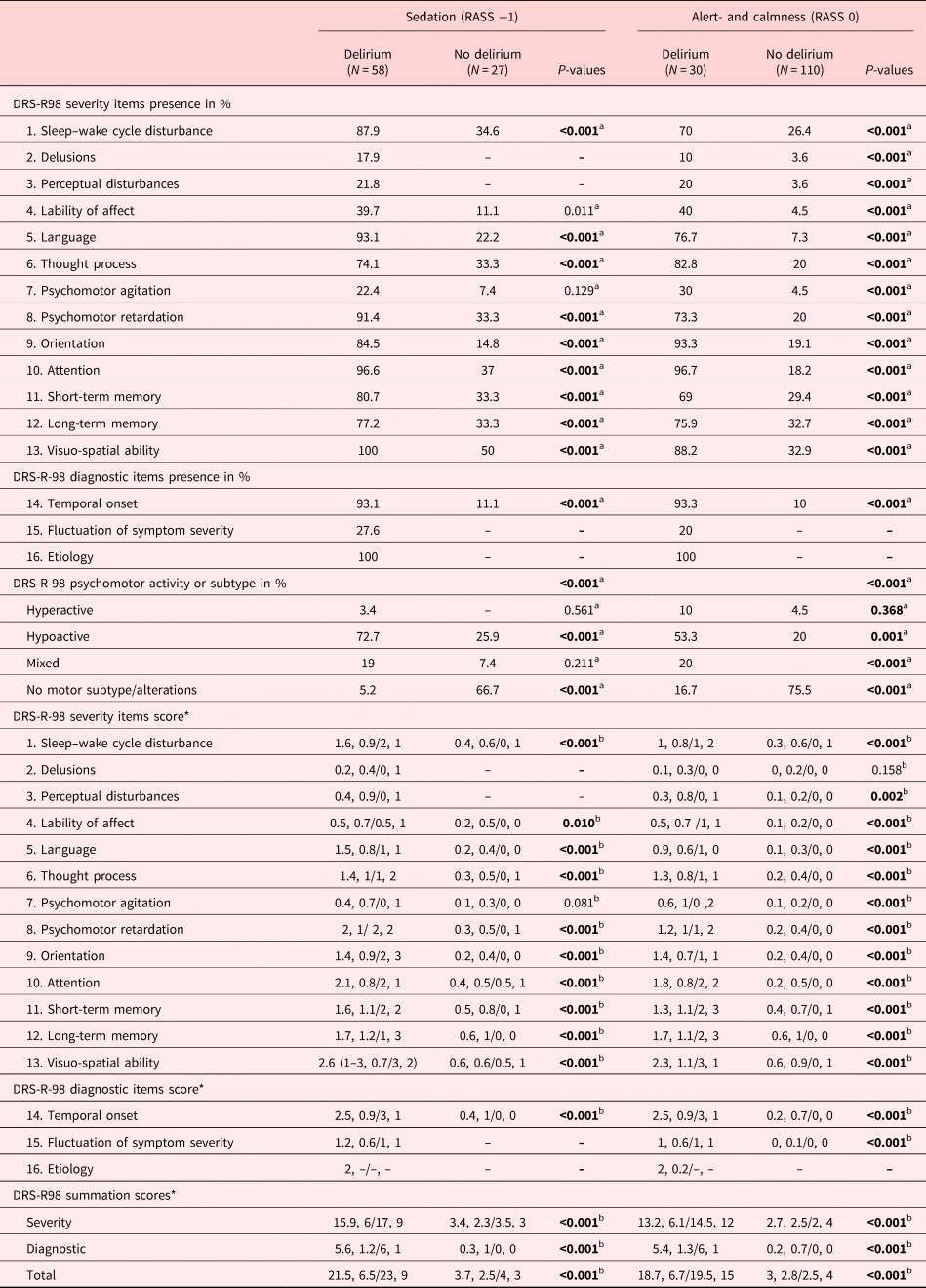

Delirium characteristics as determined by the DRS-R-98 in the drowsy patient

The following items of the DRS-R-98 indicated the presence of delirium (Table 3): sleep–wake cycle disturbances, language abnormalities, thought process alterations, psychomotor retardation, disorientation, inattention, short- and long-term memory impairment, as well as visuo-spatial impairment. Perceptual disturbances or delusions occurred only in patients with delirium. Among the diagnostic items, the temporal onset was characteristic of the delirious and fluctuations and underlying etiology were only documented in the delirious. Differences also existed in the allocation of subtypes: Those with delirium were more of the hypoactive or mixed subtype, whereas no motor alterations were recorded in those without delirium.

Table 3. Characteristics of delirium as described by the DRS-R-98 dependent on RASS scores of −1 and 0

Bold values are statistically significant, <0.05.

DRS-R-98, Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-1998; RASS, Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale.

a Pearson's χ 2 test.

b Mann–Whitney's U-test (MWU).

* Mean, SD (standard deviation)/median, IQR (interquartile range).

By their severity, the same items distinguished those with delirium from those without. In particular, inattention and the visuo-spatial impairment were more severe and the temporal onset faster. Expectedly, all DRS-R-98 summation scores — severity, diagnostic and total — were higher in patients with delirium.

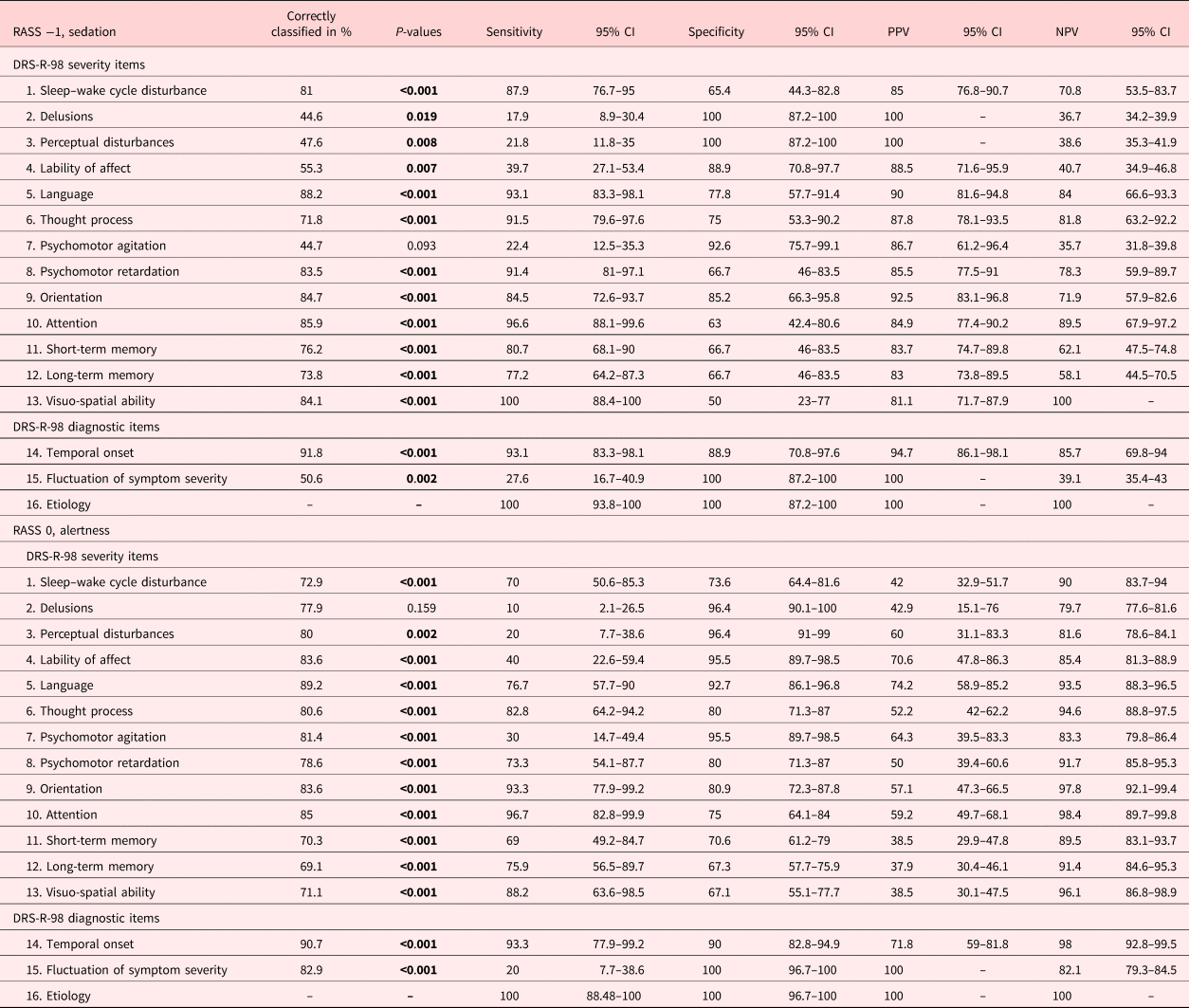

As determined by the discriminant analysis (Table 4), the same items, sleep–wake cycle disturbances, language abnormalities, thought process alterations, psychomotor retardation, disorientation, inattention, short- and long-term memory impairment, as well as visuo-spatial impairment in addition to the temporal onset, allowed the correct classification of delirium indicated by percentages ranging from 74 to 88%. Conversely, perceptual disturbances, delusions, affective lability, psychomotor agitation, or fluctuations were items, which identified delirium less correctly (45–51%).

Table 4. Correct classifications, sensitivities and specificities, as well as positive and negative predictive values (PPVs and NPVs) at RASS −1 and 0

Bold values are statistically significant, <0.05.

DRS-R-98, Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-1998; RASS, Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale; CI, confidence interval.

Similarly, these items — in addition to the underlying etiology — were very sensitive in the detection of delirium sensitivities, whereas perceptual disturbances, delusions, affective lability, and psychomotor agitation were not. Conversely, these items were very specific for delirium, in addition to language abnormalities and disorientation. In particular, perceptual disturbances, delusions, fluctuations of symptom severity and the underlying etiology reached perfect specificities. The positive prediction was high throughout items and reached perfect with respect to perceptual disturbances, delusions, fluctuation of symptomatology, and underlying etiology. The negative prediction was low for the same items that reached low sensitivities in addition to memory impairment.

Delirium in the presence of alert- or calmness (RASS = 0)

Description of the delirious versus the nondelirious sample

The calm and alert patients with delirium were older, assessed at a later day and were more commonly sedated during assessment, stayed longer on the ICU, their disease was more severe as evidenced by the SAPSs, the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was higher, as well as higher doses of haloperidol and pipamperone were required (Table 2).

Delirium characteristics as determined by the DRS-R-98 in the alert and calm patient

By the presence of delirium symptomatology as recorded by the DRS-R-98 items (Table 3), each individual symptom — with the exception of fluctuation of symptom severity and the underlying etiology that were not recorded in those without delirium — was documented at a higher rate. Further, the motor subtypes of delirium, hyperactive, hypoactive and mixed, presented in the delirious, whereas no motor alterations presented in the nondelirious. With respect to the severity of the individual DRS-R-98-items, each symptom was more severe except for delusions.

Each individual DRS-R-98 item — except for the rarely documented delusions and the underlying etiology, only documented in the delirious — correctly classified delirium to a substantial degree in the alert and calm patients (Table 4).

Comparable to the drowsy, delirious patients, the DRS-R-98 items were very sensitive, except for perceptual disturbances, delusions, affective lability, psychomotor agitation, and fluctuation of symptom severity. The specificities and negative prediction remained high through the items, whereas the positive prediction was only moderate.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This study aimed to identify symptoms serving the recognition of delirium in the intensive care setting. Sleep–wake cycle disturbances, language abnormalities, thought process alterations, psychomotor retardation, disorientation, inattention, short- and long-term memory impairment, as well as visuo-spatial impairment were characteristics for those patients with delirium. Perceptual disturbances or delusions occurred only in the drowsy patients with delirium. Further, the diagnostic items, the temporal onset, and underlying etiology were highly indicative of delirium. As evidenced by severity, both visual–spatial disturbances and inattention indicated delirium, even more in the drowsy than in the alert and calm patient.

In the presence of drowsiness, the correct classification, sensitivities and negative prediction of delirium were substantial for sleep–wake cycle disturbances, psychomotor retardation, and cognitive domain, namely language abnormalities, thought process alterations, disorientation, inattention, memory, and visuo-spatial impairment. By their specificity and positive prediction, all items reached clinically relevant levels; however, perceptual disturbances, delusions, fluctuation of symptom severity, and the underlying etiology reached perfect levels.

In the presence of alert- and calmness, the correct classification, specificity and negative prediction of items was clinically relevant throughout all items. Only the sensitivities for delusions, perceptual disturbances, psychomotor agitation, and fluctuation of symptom severity reached lower levels, and items that were less helpful in the positive prediction were sleep–wake cycle disturbances, delusions, short- and long-term memory, as well as visuo-spatial impairment.

The allocation of delirium subtypes was also different: The motoric subtypes prevailed in those with delirium, whereas no motor alterations were recorded in those without delirium.

Comparison to the existing literature

Studies assessing delirium in the intensive care setting with the DRS-R-98 are rare. Due to limited communication abilities, other instruments, such as the CAM-ICU (Ely et al., Reference Ely, Inouye and Bernard2001) or ICDSC (Devlin et al., Reference Devlin, Fong and Schumaker2007), are routinely used; however, they provide a less detailed characterization of delirium (Luetz et al., Reference Luetz, Heymann and Radtke2010). In concordance with these findings, one study using the DRS-R-98 characterized delirium in the intensive care setting with increased sleep–wake cycle disturbances, lability of affect, thought disorder, inattention and disorientation, as well as short- and long-term memory impairment. Delusions were rarely recorded (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Malhotra and Grover2012; Lahariya et al., Reference Lahariya, Grover and Bagga2016). Although perceptual disturbances and delusions were rarely recorded in the patients studied, both proved to be very specific and positively predicted delirium.

Altogether these findings compare studies across hospital settings, although the rates of delirium across hospital settings were lower and the rates of perceptual disturbances and delusions often higher (Stagno et al., Reference Stagno, Gibson and Breitbart2004; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, de Jonghe and Schieveld2008).

Inattention has been identified as a core feature of delirium (Fong et al., Reference Fong, Tulebaev and Inouye2009), and tests were evaluated solely focusing on inattention in the general healthcare setting (O'Regan et al., Reference O'Regan, Ryan and Boland2014). From these findings, the severity of both visuo-spatial disability and inattention indicated delirium, particularly in the drowsy patient. Testing visuo-spatial abilities, such as copying designs, the clock-drawing test (O'Regan et al., Reference O'Regan, Maughan and Liddy2017), or the combination of attention and visuo-spatial abilities, the Spatial Span Forward-test (O'Regan et al., Reference O'Regan, Ryan and Boland2014) have only limited value in the intensive care setting due to the patients’ limited graphic abilities and mobility. However, inattention is easily measured, and the value of a single test for attention, such as the reciting the months of the years backwards (MOTYB) or the digit-span test (O'Regan et al., Reference O'Regan, Ryan and Boland2014, Reference O'Regan, Maughan and Liddy2017), as promoted across the general health care setting, as a single measure for delirium on the ICU remains to be studied.

Although screening tools, such as the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) (Bergeron et al., Reference Bergeron, Dubois and Dumont2001), and diagnostic tools, such as the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) (Ely et al., Reference Ely, Inouye and Bernard2001) exist, from a previous study, both fell short in the daily clinical routine, missing every other or a third of patients with delirium (Boettger et al., Reference Boettger, Nunez and Meyer2017b). Therefore, the need for a brief, reliable screening tool is vast.

In contrast, from these findings, in the screening for delirium, inattention as a marker reached an overall 97.5% sensitivity and 79% specificity (CI 93–99.5% and 72.1–85%, respectively).

Further, with the advent of DSM 5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which defines the disturbance of consciousness as either level of consciousness such as alert and calm or content of consciousness — i.e. inattention, consciousness has been better defined than in DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) using alertness and awareness. Thus, tests for attention for the detection of delirium support the more recent approach of DSM 5.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths such as prospectively screening and rating close to 300 patients for delirium using the DRS-R-98 and the gold standard for the diagnosis of delirium, the DSM-IV-TR criteria. With respect to the DSM-IV-TR-determined diagnosis of delirium, the inter-rater agreement was perfect. Limitations included the high prevalence of hypoactive delirium, which was indebted to the critical care population studied, the absence of baseline cognitive recording owed to the setting of the study; thus, pre-existing cognitive disorders could not be excluded despite screening the medical record for these. Further, this study was cross-sectional and characterized delirium in the drowsy or alert and calm, aiming to identify symptom clusters allowing the detection of delirium. When the study was approved by the ethics committee, DSM-IV-TR was the current diagnostic manual. Since then, DSM 5 has been published (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); however, it was not possible to switch the design in the middle of the study. Limited by the design of the study identifying patients with delirium and including them after the consent, it was not possible to describe all admissions to the ICU.

Further studies are required in order to assess delirium in the intensive care setting more, and in particular, the value of inattention as a potential brief marker or screening for delirium.

Conclusion

In summary, items allowing the correct identification of delirium were sleep–wake cycle disturbances, language abnormalities, thought process alterations, psychomotor retardation, disorientation, inattention, short- and long-term memory impairment, as well as visuo-spatial impairment, and diagnostically the temporal onset. Conversely, perceptual disturbances, delusions, affective lability, psychomotor agitation, or fluctuations were items, which identified delirium less correctly. In the drowsy patient, perceptual disturbances, delusions, and fluctuation of symptom severity were predictive of delirium. Further, the severity of inattentiveness and visuo-spatial impairment indicated delirium, and inattentiveness, which can be easily measured with a single test, such as the MOTYB or digit span test, could be a specific marker for delirium in the intensive care setting.

Conflict of interest

None.